Abstract

Importance

For critically ill adults undergoing emergency tracheal intubation, failure to intubate the trachea on the first attempt occurs in up to 20% of cases and is associated with severe hypoxemia and cardiac arrest. Whether using a tracheal tube introducer ("bougie") increases the likelihood of successful intubation compared with using an endotracheal tube with stylet remains uncertain.Objective

To determine the effect of use of a bougie vs an endotracheal tube with stylet on successful intubation on the first attempt.Design, setting, and participants

The Bougie or Stylet in Patients Undergoing Intubation Emergently (BOUGIE) trial was a multicenter, randomized clinical trial among 1102 critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation in 7 emergency departments and 8 intensive care units in the US between April 29, 2019, and February 14, 2021; the date of final follow-up was March 14, 2021.Interventions

Patients were randomly assigned to use of a bougie (n = 556) or use of an endotracheal tube with stylet (n = 546).Main outcomes and measures

The primary outcome was successful intubation on the first attempt. The secondary outcome was the incidence of severe hypoxemia, defined as a peripheral oxygen saturation less than 80%.Results

Among 1106 patients randomized, 1102 (99.6%) completed the trial and were included in the primary analysis (median age, 58 years; 41.0% women). Successful intubation on the first attempt occurred in 447 patients (80.4%) in the bougie group and 453 patients (83.0%) in the stylet group (absolute risk difference, -2.6 percentage points [95% CI, -7.3 to 2.2]; P = .27). A total of 58 patients (11.0%) in the bougie group experienced severe hypoxemia, compared with 46 patients (8.8%) in the stylet group (absolute risk difference, 2.2 percentage points [95% CI, -1.6 to 6.0]). Esophageal intubation occurred in 4 patients (0.7%) in the bougie group and 5 patients (0.9%) in the stylet group, pneumothorax was present after intubation in 14 patients (2.5%) in the bougie group and 15 patients (2.7%) in the stylet group, and injury to oral, glottic, or thoracic structures occurred in 0 patients in the bougie group and 3 patients (0.5%) in the stylet group.Conclusions and relevance

Among critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, use of a bougie did not significantly increase the incidence of successful intubation on the first attempt compared with use of an endotracheal tube with stylet.Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03928925Free full text

Effect of Use of a Bougie vs Endotracheal Tube With Stylet on Successful Intubation on the First Attempt Among Critically Ill Patients Undergoing Tracheal Intubation

Key Points

Question

In critically ill adult patients undergoing tracheal intubation, does use of a tracheal tube introducer (“bougie”) increase the incidence of successful intubation on the first attempt, compared with use of an endotracheal tube with stylet?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 1102 critically ill adults, successful intubation on the first attempt was 80.4% with use of a bougie and 83.0% with use of an endotracheal tube with stylet, a difference that was not statistically significant.

Meaning

Among critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, use of a bougie did not significantly increase the incidence of successful intubation on the first attempt compared with use of an endotracheal tube with stylet.

Abstract

Importance

For critically ill adults undergoing emergency tracheal intubation, failure to intubate the trachea on the first attempt occurs in up to 20% of cases and is associated with severe hypoxemia and cardiac arrest. Whether using a tracheal tube introducer (“bougie”) increases the likelihood of successful intubation compared with using an endotracheal tube with stylet remains uncertain.

Objective

To determine the effect of use of a bougie vs an endotracheal tube with stylet on successful intubation on the first attempt.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Bougie or Stylet in Patients Undergoing Intubation Emergently (BOUGIE) trial was a multicenter, randomized clinical trial among 1102 critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation in 7 emergency departments and 8 intensive care units in the US between April 29, 2019, and February 14, 2021; the date of final follow-up was March 14, 2021.

Interventions

Patients were randomly assigned to use of a bougie (n =

= 556) or use of an endotracheal tube with stylet (n

556) or use of an endotracheal tube with stylet (n =

= 546).

546).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was successful intubation on the first attempt. The secondary outcome was the incidence of severe hypoxemia, defined as a peripheral oxygen saturation less than 80%.

Results

Among 1106 patients randomized, 1102 (99.6%) completed the trial and were included in the primary analysis (median age, 58 years; 41.0% women). Successful intubation on the first attempt occurred in 447 patients (80.4%) in the bougie group and 453 patients (83.0%) in the stylet group (absolute risk difference, −2.6 percentage points [95% CI, −7.3 to 2.2]; P =

= .27). A total of 58 patients (11.0%) in the bougie group experienced severe hypoxemia, compared with 46 patients (8.8%) in the stylet group (absolute risk difference, 2.2 percentage points [95% CI, −1.6 to 6.0]). Esophageal intubation occurred in 4 patients (0.7%) in the bougie group and 5 patients (0.9%) in the stylet group, pneumothorax was present after intubation in 14 patients (2.5%) in the bougie group and 15 patients (2.7%) in the stylet group, and injury to oral, glottic, or thoracic structures occurred in 0 patients in the bougie group and 3 patients (0.5%) in the stylet group.

.27). A total of 58 patients (11.0%) in the bougie group experienced severe hypoxemia, compared with 46 patients (8.8%) in the stylet group (absolute risk difference, 2.2 percentage points [95% CI, −1.6 to 6.0]). Esophageal intubation occurred in 4 patients (0.7%) in the bougie group and 5 patients (0.9%) in the stylet group, pneumothorax was present after intubation in 14 patients (2.5%) in the bougie group and 15 patients (2.7%) in the stylet group, and injury to oral, glottic, or thoracic structures occurred in 0 patients in the bougie group and 3 patients (0.5%) in the stylet group.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, use of a bougie did not significantly increase the incidence of successful intubation on the first attempt compared with use of an endotracheal tube with stylet.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03928925

Introduction

Approximately 1.6 million critically ill adults undergo tracheal intubation annually in the US.1,2 Failure to intubate the trachea on the first attempt occurs in up to 20% of tracheal intubations in the emergency department (ED) or intensive care unit (ICU) and is associated with an increased risk of severe hypoxemia, cardiac arrest, and death.3,4

Two devices are commonly used to facilitate tracheal intubation: a stylet or a tracheal tube introducer (referred to as a “bougie”).5 A stylet is a malleable metal rod placed inside the endotracheal tube to facilitate its passage into the trachea. A bougie is a thin plastic rod that is passed into the trachea, over which the endotracheal tube is inserted. Historically, most emergency tracheal intubations in the US have been performed using a stylet, with use of a bougie reserved for difficult intubations.5,6 However, 3 recent observational studies and 1 randomized trial found that routinely using a bougie rather than a endotracheal tube with a stylet was associated with an increased incidence of intubation on the first attempt.7,8,9 The only randomized clinical trial directly comparing the devices during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults was limited by its conduct in a single site in which clinicians routinely used the bougie on the first intubation attempt before the trial.10 Despite that limitation, recent expert recommendations encourage routine use of a bougie for tracheal intubation.11,12

The Bougie or Stylet in Patients Undergoing Intubation Emergently (BOUGIE) trial was conducted to compare the effect of using a bougie vs an endotracheal tube with stylet on outcomes of tracheal intubation in EDs and ICUs across multiple health systems. The hypothesis was that use of a bougie would result in a higher incidence of successful intubation on the first attempt, compared with use of a stylet.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

This multicenter, parallel-group, unblinded, pragmatic, randomized clinical trial compared use of a bougie with use of an endotracheal tube with stylet for tracheal intubation of critically ill adults. The trial was approved with waiver of informed consent by the central institutional review board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the local institutional review board at each trial site through reliance agreement or primary review. The trial was overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board and registered before initiation of enrollment. Enrollment began on April 29, 2019, was paused from February 28, 2020, until August 24, 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, and concluded on February 14, 2021. The protocol and statistical analysis plan (Supplement 1) were submitted for publication before enrollment concluded.13

Trial Sites and Patient Population

The trial was conducted at 15 sites, including 7 EDs and 8 adult ICUs in 11 hospitals across the US. Patients were eligible if they were undergoing tracheal intubation with the planned use of sedation and a nonhyperangulated (eg, Macintosh [curved] or Miller [straight]) laryngoscope blade. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, were incarcerated, had an immediate need for tracheal intubation without time for randomization, or if the clinician performing the intubation procedure (referred to as the “operator”) determined that use of a bougie or a stylet was either required or contraindicated. Details of the trial sites and complete lists of inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Supplement 2.

Randomization

Patients underwent randomization in a 1:1 ratio to intubation using a bougie or an endotracheal tube with stylet, according to a computer-generated list using randomly permuted blocks of 2, 4 and 6, stratified according to trial site. Trial-group assignments were placed in sequentially numbered opaque envelopes and remained concealed until after enrollment. Given the nature of the intervention, operators and research personnel were aware of trial-group assignments after randomization.

Trial Interventions

Before beginning enrollment, operators received structured education regarding best practices in use of a bougie and endotracheal tube with stylet via a standardized training video14 and in-person training from the site principal investigator.

During the trial, for patients assigned to the bougie group, operators were instructed to use a bougie for the first attempt at tracheal intubation. Operators were instructed to pass the bougie into the trachea, have an assistant load the endotracheal tube (without a stylet) onto the bougie, advance the tube over the bougie through the vocal cords to the desired depth, and withdraw the bougie and the laryngoscope.

For patients assigned to the stylet group, operators were instructed to use an endotracheal tube with a malleable stylet for the first attempt at tracheal intubation. The trial protocol recommended shaping the stylet straight with a distal bend of 25° to 35°.14

As a pragmatic trial, delivery of the assigned intervention occurred within routine clinical care, and trial group assignment determined only whether a bougie or an endotracheal tube with stylet was used during the first attempt at tracheal intubation. All other aspects of the procedure were deferred to the operator, including laryngoscope selection, choice of induction medication, and use of a bougie or a stylet during subsequent attempts at intubation if the first attempt was unsuccessful.

Data Collection

A trained, independent observer collected data on the outcomes of the procedure, including the number of intubation attempts, time between induction of sedation and intubation, peripheral oxygen saturation at induction, and the lowest oxygen saturation between induction and 2 minutes after tracheal intubation. Immediately after each intubation, the operator reported the laryngoscope used, the Cormack-Lehane grade of glottic view,15 whether successful intubation occurred on the first attempt, the presence of difficult airway characteristics (including obesity, body fluid obscuring the glottis, cervical spine immobilization, and facial trauma), the occurrence of complications, and the operator’s prior intubation experience, classified as the total number of prior tracheal intubations performed and the total number of prior tracheal intubations performed using a bougie.

Research personnel collected from the medical record data on baseline characteristics, management before and after laryngoscopy, and clinical outcomes. Race and ethnicity were reported by patients or their surrogates as part of clinical care. They were collected from the electronic health record by research personnel using fixed categories to facilitate assessment of the representativeness of the trial population and the generalizability of trial results.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was successful intubation on the first attempt, defined as a single insertion of a laryngoscope blade into the mouth and either a single insertion of a bougie into the mouth followed by a single insertion of an endotracheal tube into the mouth or a single insertion of an endotracheal tube with stylet into the mouth. The single prespecified secondary outcome was the incidence of severe hypoxemia, defined as an oxygen saturation less than 80% during the interval between induction and 2 minutes after tracheal intubation. Exploratory procedural outcomes, procedural complications, and clinical outcomes are described in Supplement 2.

Sample Size Calculation

Details regarding the determination of the sample size have been reported.13 Assuming that 84% of patients in the stylet group would experience successful intubation on the first attempt16 and anticipating that less than 5% of patients would be missing data for the primary outcome, enrollment of 1106 patients was determined to provide 80% power at a 2-sided α level of .05 to detect an absolute difference of 6% in the primary outcome between groups. A difference of this magnitude has been considered clinically meaningful in the design of prior airway management trials.10,17,18

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis was an unadjusted comparison of the primary outcome between patients in the 2 trial groups using the χ2 test, with results reported as an absolute risk difference and 95% CIs. Patients were analyzed according to the group to which they were randomly assigned. The primary analysis included all randomized patients except those withdrawn from the study for prisoner status identified after intubation. Sensitivity analyses used alternate definitions of the trial population and primary outcome, including (1) an analysis that defined successful intubation on the first attempt using only laryngoscopy attempts, (2) an analysis that considered intubations with crossover in the assigned intervention as not achieving successful intubation on the first attempt, (3) an analysis that limited the population to intubations performed by operators who had completed at least 10 previous intubations, and (4) an analysis that limited the population to intubations performed by operators who had completed at least 5 previous intubations using a bougie (Supplement 2).

In additional analyses adjusting for baseline covariates, a generalized linear mixed-effects model using a logit link function was fit for the primary outcome, with random effects for operator and study site and fixed effects for trial group and the following prespecified baseline covariates: age, sex, race and ethnicity, body mass index, the operator’s prior number of tracheal intubations, and location (ED vs ICU). A second model also included use of a video laryngoscope, presence of difficult airway characteristics, and the Cormack-Lehane grade of glottic view.15 In adjusted analyses, missing data for baseline covariates was imputed using multiple imputations. Effect modification was assessed by including an interaction term between prespecified baseline covariables and trial group assignment in the above models (Supplement 2).

After the enrollment of 553 patients, the data and safety monitoring board conducted a single interim analysis to review adverse event data and compare the incidence of successful intubation on the first attempt between groups using a Haybittle–Peto stopping boundary for efficacy of P <

< .001. For the final analysis of the primary outcome, a 2-sided P value less than .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Between-group differences in secondary and exploratory outcomes were reported using complete-case analysis with the use of point estimates and 95% CIs. The widths of the CIs have not been adjusted for multiplicity and should not be used to infer definitive differences in treatment effects between groups. Findings for these analyses should be interpreted as exploratory.

.001. For the final analysis of the primary outcome, a 2-sided P value less than .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Between-group differences in secondary and exploratory outcomes were reported using complete-case analysis with the use of point estimates and 95% CIs. The widths of the CIs have not been adjusted for multiplicity and should not be used to infer definitive differences in treatment effects between groups. Findings for these analyses should be interpreted as exploratory.

All analyses were performed using R version 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Patients

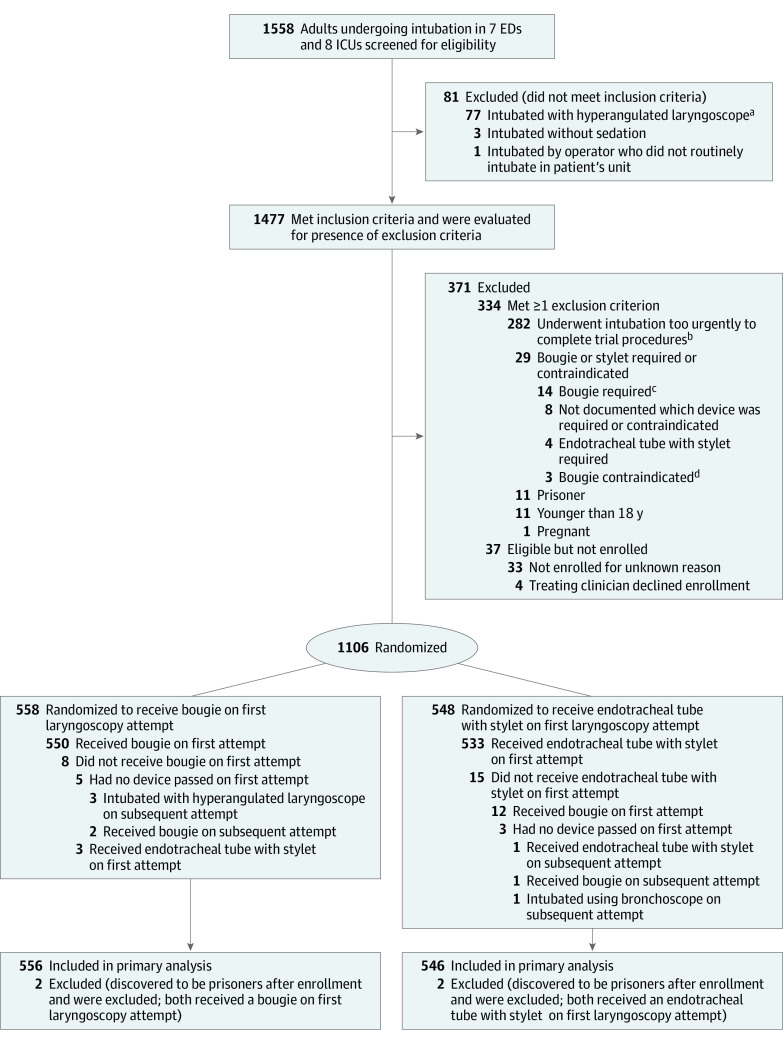

Of the 1558 patients screened, 1106 (71.0%) were enrolled. Four patients were determined to be prisoners after enrollment and were excluded from subsequent data collection and analysis. The remaining 1102 patients were included in the primary analysis (Figure 1). The median age was 58 years, and 41.0% were women. Altered mental status (44.6%) and acute respiratory failure (31.5%) were the most common reasons for tracheal intubation, and 42.0% of patients had 1 or more difficult airway characteristics. A total of 556 patients (50.5%) were assigned to the bougie group and 546 patients (49.5%) to the stylet group (Table 1; eTables 1-4 in Supplement 2).

ED indicates emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

aAmong 77 patients intubated with a hyperangulated laryngoscope, 32 were at a single trial site at which operators preferred a hyperangulated blade when video laryngoscopy was to be performed. The indication for the selection of a hyperangulated blade for the remaining 45 patients was not recorded.

bAmong 282 patients who underwent intubation too urgently to complete trial procedures, 28 were at trial sites that recorded the reason for the urgency. Of these, 17 patients were experiencing cardiac arrest, 3 had ongoing hematemesis, 3 had severe hypoxemia, 1 had an acute cerebrovascular accident requiring urgent transport, 1 had massive hemoptysis, 1 had a tension pneumothorax, 1 was experiencing a seizure, and 1 had a traumatic injury requiring an emergency procedure.

cReasons a bougie was required: 3 patients with a history of a prior difficult intubation, 3 with body fluids obscuring the glottic view, 1 with morbid obesity, and 7 with unknown reason.

dReasons a bougie was contraindicated: 1 patient with recent lung transplant and concern for damage to the anastomoses; 2 with unknown reason.

Table 1.

| Characteristic | Group, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

Bougie (n = = 556) 556) | Stylet (n = = 546) 546) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 58 (42-69) | 58 (44-67) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 223 (40.1) | 229 (41.9) |

| Male | 333 (59.9) | 317 (58.1) |

| Race or ethnicity, No./total No. (%)a | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2/547 (0.4) | 3/541 (0.6) |

| Asian | 12/547 (2.2) | 13/541 (2.4) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 137/547 (25.0) | 127/541 (23.5) |

| Hispanic | 49/547 (9.0) | 55/541 (10.2) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0/547 | 1/541 (0.2) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 340/547 (62.2) | 336/541 (62.1) |

| Other | 34/547 (6.2) | 35/541 (6.5) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR)b | 26.1 (22.7-31.3) | 26.6 (22.7-31.3) |

| Indication for intubationc | ||

| Altered mental status | 246 (44.2) | 246 (45.1) |

| Acute respiratory failure | 181 (32.6) | 166 (30.4) |

| Emergency procedure | 36 (6.5) | 31 (5.7) |

| Seizure | 26 (4.7) | 22 (4.0) |

| Agitation | 14 (2.5) | 17 (3.1) |

| Cardiac arrest | 13 (2.3) | 14 (2.6) |

| Upper airway obstruction | 13 (2.3) | 12 (2.2) |

| Hemodynamic instability | 8 (1.4) | 11 (2.0) |

| Other | 19 (3.4) | 27 (4.9) |

| Location of intubation procedure | ||

| Emergency department | 350 (62.9) | 335 (61.4) |

| Intensive care unit | 206 (37.1) | 211 (38.6) |

| ≥1 difficult airway characteristicsd | 228 (41.0) | 235 (43.0) |

| Obesitye | 158 (28.4) | 158 (28.9) |

| Body fluid obscuring glottis | 50 (9.0) | 56 (10.3) |

| Cervical spine immobilization | 48 (8.6) | 56 (10.3) |

| Facial trauma | 6 (1.1) | 13 (2.4) |

| Primary diagnosis of trauma | 96 (17.3) | 100 (18.3) |

| Active medical conditionsf | ||

| Acute encephalopathy | 372 (66.9) | 393 (72.0) |

| Sepsis or septic shock | 174 (31.3) | 195 (35.7) |

| Pneumonia | 58 (10.4) | 45 (8.2) |

| Gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage | 51 (9.2) | 48 (8.8) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 30 (5.4) | 19 (3.5) |

| Cardiac arrest | 21 (3.8) | 20 (3.7) |

| COVID-19 | 17 (3.1) | 17 (3.1) |

| APACHE II score, median (IQR)g | 17 (12-22) | 17 (12-23) |

Abbreviation: APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II.

Operators

The specialty, level of training, and prior experience of the operator performing the tracheal intubation procedure are reported in Table 1 and in eTable 5 in Supplement 2. The most common operator specialty was emergency medicine (62.9%), and most operators were resident physicians (61.6%). In each group, operators had performed a median of 60 total prior tracheal intubations, with a median of 10 (IQR, 4-20) prior intubations using a bougie.

Laryngoscopy and Tracheal Intubation

A video laryngoscope was used for 421 patients (75.7%) in the bougie group and 403 patients (73.8%) in the stylet group. A total of 548 patients (98.6%) in the bougie group received a bougie on the first laryngoscopy attempt; 531 patients (97.3%) in the stylet group received an endotracheal tube with stylet on the first laryngoscopy attempt. Additional characteristics of the intubation procedure are shown in Table 2, Figure 1, and eTables 6-8 in Supplement 2.

Table 2.

| Characteristic | Group, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

Bougie (n = = 556) 556) | Stylet (n = = 546) 546) | |

| Operator | ||

| Resident | 344 (61.9) | 335 (61.4) |

| Fellow | 187 (33.6) | 186 (34.1) |

| Attending physician | 13 (2.3) | 13 (2.4) |

| Othera | 12 (2.2) | 12 (2.2) |

| Before induction | ||

| Preoxygenation methodb | ||

| Nonrebreather mask | 286 (51.4) | 291 (53.3) |

| Standard nasal cannula | 186 (33.5) | 200 (36.6) |

| Bag-mask device | 104 (18.7) | 111 (20.3) |

| Bilevel positive airway pressure | 86 (15.5) | 71 (13.0) |

| High-flow nasal cannula | 68 (12.2) | 62 (11.4) |

| None | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.4) |

| At induction | ||

| Oxygen saturationc | ||

| Median (IQR), % | 100 (97-100) | 100 (97-100) |

| <90%, No./total No. (%) | 33/533 (6.2) | 32/528 (6.1) |

| Systolic blood pressure, median (IQR), mm Hgd | 134 (115-153) | 128 (110-150) |

| Sedative administered for inductione | 545 (98.0) | 532 (97.4) |

| Neuromuscular blocking agent administerede | 539 (96.9) | 531 (97.3) |

| After induction | ||

| Laryngoscope used on first laryngoscopy attempt | ||

| Direct laryngoscope | 132 (23.7) | 142 (26.0) |

| Video laryngoscope | 421 (75.7) | 403 (73.8) |

| Storz C-MAC, No. | 298 | 276 |

| McGrath MAC, No. | 85 | 86 |

| Glidescope titanium, No. | 38 | 41 |

| Otherf | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| Device used on first laryngoscopy attempt | ||

| Bougie | 548 (98.6) | 12 (2.2) |

| Endotracheal tube with stylet | 3 (0.5) | 531 (97.3) |

| Neitherg | 5 (0.9) | 3 (0.5) |

Primary Outcome

Data for the primary outcome were available for all patients. Successful intubation on the first attempt occurred in 447 patients (80.4%) in the bougie group and in 453 patients (83.0%) in the stylet group, for a risk difference of −2.6 percentage points (95% CI, −7.3 to 2.2; P =

= .27) (Table 3; eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Successful intubation on the first attempt did not significantly differ between groups in an adjusted analysis (adjusted odds ratio, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.64 to 1.22]) (eFigures 2 and 3 and eTable 9 in Supplement 2) or multiple sensitivity analyses, including one defining successful intubation on the first attempt based only on the number of laryngoscope insertions (87.6% vs 88.6%; absolute risk difference, −1.1 percentage points [95% CI, −5.1 to 2.9]) (eTables 10 and 11 in Supplement 2). The odds of successful intubation on the first attempt did not differ significantly between groups in any of the prespecified subgroups, including among more experienced operators, among patients with difficult airway characteristics, or when a video laryngoscope was used (Figure 2; eFigures 4 and 5 and eTable 12 in Supplement 2).

.27) (Table 3; eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Successful intubation on the first attempt did not significantly differ between groups in an adjusted analysis (adjusted odds ratio, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.64 to 1.22]) (eFigures 2 and 3 and eTable 9 in Supplement 2) or multiple sensitivity analyses, including one defining successful intubation on the first attempt based only on the number of laryngoscope insertions (87.6% vs 88.6%; absolute risk difference, −1.1 percentage points [95% CI, −5.1 to 2.9]) (eTables 10 and 11 in Supplement 2). The odds of successful intubation on the first attempt did not differ significantly between groups in any of the prespecified subgroups, including among more experienced operators, among patients with difficult airway characteristics, or when a video laryngoscope was used (Figure 2; eFigures 4 and 5 and eTable 12 in Supplement 2).

Table 3.

| Outcome | Group, No. (%) | Absolute risk difference or difference in medians (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

Bougie (n = = 556) 556) | Stylet (n = = 546) 546) | ||

| Primary outcome | |||

| Successful intubation on the first attemptb | 447 (80.4) | 453 (83.0) | −2.6 (−7.3 to 2.2) |

| Secondary outcome | |||

| Lowest oxygen saturation <80%, No./total (%) | 58/526 (11.0) | 46/524 (8.8) | 2.2 (−1.6 to 6.0) |

| Exploratory procedural outcomes | |||

| Time from induction to intubation | |||

| Median (IQR), s | 124 (97-180) [n = = 543] 543] | 112 (85-157) [n = = 530] 530] | 12 (4 to 20) |

| Cormack-Lehane grade of glottic view, No./total No. (%)c | |||

| Grade 1 (best view) | 358/554 (64.6) | 335/544 (61.6) | 3.0 (−2.8 to 8.9) |

| Grade 2 | 153/554 (27.6) | 163/544 (30.0) | −2.3 (−7.9 to 3.2) |

| Grade 3 | 30/554 (5.4) | 35/544 (6.4) | −1.0 (−4.0 to 2.0) |

| Grade 4 (worst view) | 13/554 (2.3) | 11/544 (2.0) | 0.3 (−1.6 to 2.2) |

| Exploratory procedural complications | |||

| Intubation complications | 10 (1.8) | 10 (1.8) | 0 (−1.6 to 1.6) |

| Esophageal intubation | 4 (0.7) | 5 (0.9)d | |

| Injury to oral, glottic, or thoracic structures | 0 | 3 (0.5)d | |

| Witnessed aspiration during intubation | 6 (1.1) | 3 (0.5) | |

| Cardiovascular collapse within 1 h after intubatione | 68 (12.2) | 91 (16.7) | −4.4 (−8.8 to −0.1) |

| Cardiac arrest within 1 h after intubation | 10 (1.8) | 10 (1.8) | 0 (−1.7 to 1.6) |

| New pneumothorax within 48 h after intubation (post hoc outcome) | 14 (2.5) | 15 (2.7) | −0.2 (−2.3 to 1.8) |

| Exploratory clinical outcomes | |||

| Ventilator-free days, median (IQR)f | 24 (0-27) | 22 (0-26) | 2 (0.5 to 6) |

| Intensive care unit-free days, median (IQR)f | 21 (0-25) | 18 (0-25) | 3 (0 to 6) |

| Death before 28 d | 152 (27.3) | 184 (33.7) | −6.4 (−12.0 to −0.8) |

=

= .27). Details of management when intubation did not occur on the first attempt are reported in eTable 15 in Supplement 2.

.27). Details of management when intubation did not occur on the first attempt are reported in eTable 15 in Supplement 2.

Shown are the odds ratios and 95% CIs for the primary outcome in the bougie group compared with the stylet group, after adjustment for prespecified baseline covariates. The Cormack-Lehane grade of glottic view15 ranges from grade 1 (all or most of the glottic opening is seen) to grade 4 (neither glottis nor epiglottis are seen). The prespecified difficult airway characteristics included in this effect modification analysis were obesity (body mass index >30 [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared]), cervical immobilization, and facial trauma. ED indicates emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

Secondary Outcome

A total of 58 patients (11.0%) in the bougie group experienced an oxygen saturation less than 80%, compared with 46 patients (8.8%) in the stylet group (absolute risk difference, 2.2 percentage points [95% CI, −1.6 to 6.0]) (Table 3).

Exploratory Outcomes

The median time interval from induction to tracheal intubation was 124 seconds (IQR, 97-180) in the bougie group and 112 seconds (IQR, 85-157) in the stylet group, for a median difference of 12 seconds (95% CI, 4 to 20) (eFigures 1 and 6 in Supplement 2). The incidence of airway complications, which included esophageal intubation, injury to airway structures, and witnessed aspiration during intubation, was 1.8% in each group. The incidence of postintubation pneumothorax was 2.5% in the bougie group and 2.7% in the stylet group (Table 3; eTables 13 and 14 in Supplement 2). A total of 68 patients (12.2%) in the bougie group experienced the composite outcome of cardiovascular collapse, compared with 91 patients (16.7%) in the stylet group (risk difference, −4.4 percentage points [95% CI, −8.8 to −0.1]). Death prior to day 28, censored at hospital discharge, occurred in 152 patients (27.3%) in the bougie group and 184 patients (33.7%) in the stylet group (absolute risk difference, −6.4 percentage points [95% CI, −12.0 to −0.8]).

Discussion

In this multicenter, randomized trial, use of a bougie for tracheal intubation of critically ill adults did not significantly increase the incidence of successful intubation on the first attempt, compared with use of an endotracheal tube with stylet.

Emergency tracheal intubation is a common and potentially lifesaving procedure, with limited prior data informing whether routine use of a bougie is superior to the common practice of using an endotracheal tube with stylet. Prior research has largely been limited to small studies enrolling patients undergoing elective procedures in the operating room in whom difficult airway conditions have been artificially created.19,20 Only 1 prior randomized clinical trial compared the use of a bougie with the use of an endotracheal tube with stylet for tracheal intubation in settings outside of the operating room.10 In that prior trial, conducted in a single academic ED, the rate of successful intubation on the first laryngoscopy attempt was 98% in the bougie group and 87% in the stylet group. In the current trial, the rate of successful intubation on the first attempt was lower, with no significant difference between trial groups. Because the current trial defined the primary outcome as a single insertion of both the blade and the bougie or tube, a prespecified sensitivity analysis of the current trial was performed using the primary outcome definition from the prior trial (successful intubation during the first insertion of a laryngoscope, regardless of the number of bougie or tube insertions), which demonstrated that approximately 88% of patients in each trial group experienced the outcome—comparable to the rate of 87% observed in the stylet group in the prior trial.

The difference in findings between the current trial and the prior trial might be explained by differences in patients, operators, or intubation context. Use of a bougie has been suggested to have the greatest effect for patients with difficult airway characteristics10,21,22 or when the larynx cannot be fully visualized.10,19,23,24,25,26 The current trial, however, did not demonstrate a benefit to use of a bougie among the 463 patients with difficult airway characteristics or among the 405 patients in whom the larynx was incompletely visualized. Similarly, the type of laryngoscope (direct vs video laryngoscope) did not appear to modify the effect of bougie use on successful intubation.

An operator’s training and experience performing tracheal intubation, overall or with a specific device, may influence the likelihood of successful intubation on the first attempt.27,28 In the prior trial, all operators were resident or attending physicians in a single ED in which the majority of intubations before the trial were performed using a bougie rather than an endotracheal tube with a stylet.7 The current trial included 322 operators from 15 EDs and ICUs, ranging from resident physicians who had never before performed tracheal intubation to attending physicians with thousands of prior intubations. The average operator had performed a median of 60 prior intubations, with a median of 10 of those performed using a bougie. In effect modification analyses, use of a bougie did not appear to be beneficial among operators who had performed a greater number of total prior intubations or a greater number of prior intubations using a bougie. These results suggest that, for operators who commonly use an endotracheal tube with stylet, introducing use of a bougie is unlikely to increase the rate of successful intubation on the first attempt. Whether results would have differed among operators who have already incorporated routine use of a bougie on the first attempt into their practice is unknown.8,9,10

The effect of a procedural intervention on outcomes depends on the context in which the procedure is performed. Tracheal intubation occurs in a context determined by the physical environment, organizational resources and practices, team composition and dynamics, operator training and cognitive performance, and other nontechnical factors.29,30 The effects of bougie use observed may not generalize to contexts for tracheal intubation not represented in this trial.

Several exploratory findings of this trial should be viewed as hypothesis-generating. First, the time from induction of sedation to intubation was numerically 12 seconds longer in the bougie group, the clinical significance of which is uncertain. Second, airway injury and pneumothorax were uncommonly observed in both groups, contrary to the notion that use of a bougie increases the risk of iatrogenic airway injury,31 but the trial was underpowered for definitive assessment of these rare safety outcomes. Third, the risks of periprocedural cardiovascular collapse and death by day 28 were numerically lower in the bougie group. Because use of a bougie did not influence procedural process measures, the mechanism by which bougie use would influence these outcomes is unclear and these differences may be attributable to chance.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the trial excluded patients for whom the urgency of intubation precluded performance of trial procedures, patients intubated using a hyperangulated laryngoscope, and patients for whom use of a bougie was specifically indicated. Thus, the results of the trial may not apply to patients being intubated under specific urgent circumstances (eg, cardiac arrest), patients being intubated with a hyperangulated laryngoscope, or patients known to have abnormal airway anatomy. Second, although operator experience did not appear to modify the relationship between use of a bougie and successful intubation on the first attempt, most operators in this trial had limited previous experience intubating using a bougie, and some had limited experience performing intubation overall. Therefore, the results may not apply to operators with extensive experience intubating or intubating using a bougie. Third, the nature of the trial intervention precluded blinding of operators or observers. Fourth, the between-group comparisons may be underpowered to rule out clinically important differences in specific subgroups. Fifth, this trial evaluated use of a bougie on the first tracheal intubation attempt and does not inform the use of a bougie after a failed first intubation attempt.

Conclusions

Among critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, use of a bougie did not significantly increase the incidence of successful intubation on the first attempt compared with use of an endotracheal tube with stylet.

Notes

Supplement 1.

Study Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

Supplement 2.

List of the BOUGIE Investigators

List of Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group Members

Supplemental Methods

eFigure 1. Cumulative Proportion of Patients Successfully Intubated

eFigure 2. Calibration Plot for the First Model Used for Adjusted Analysis of the Primary Outcome

eFigure 3. Calibration Plot for the Second Model Used for Adjusted Analysis of the Primary Outcome

eFigure 4. Successful Intubation on the First Attempt by Prior Operator Experience

eFigure 5. Successful Intubation on the First Attempt by Site

eFigure 6. Cumulative Proportion of Patients Successfully Intubated on the First Attempt

eTable 1. Chronic Comorbidities

eTable 2. Active Medical Conditions at the Time of Intubation

eTable 3. Primary Indication for Tracheal Intubation

eTable 4. Difficult Airway Characteristics

eTable 5. Operator Characteristics

eTable 6. Characteristics of the Intubation Procedure With Marginal Estimates

eTable 7. Additional Characteristics of the Intubation Procedure

eTable 8. Patients Who Did Not Receive the Assigned Device on the First Laryngoscope Attempt

eTable 9. Multivariable Models for Successful Intubation on the First Attempt

eTable 10. Prespecified Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 11. Post hoc Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 12: Additional Subgroup Analyses of the Primary Outcome

eTable 13. Additional Procedural Outcomes

eTable 14. Adverse Events

eTable 15. Management When Intubation Did Not Occur on the First Attempt

eReferences

Supplement 3.

Nonauthor Collaborators. BOUGIE Investigators and the members of the Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.22002

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/articlepdf/2787158/jama_driver_2021_oi_210133_1640292640.82087.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/118444145

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1001/jama.2021.22002

Article citations

The times are changing: A primer on novel clinical trial designs and endpoints in critical care research.

Am J Health Syst Pharm, 81(18):890-902, 01 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38742701

[Indications and success rate of endotracheal emergency intubation in clinical acute and emergency medicine].

Anaesthesiologie, 73(8):511-520, 02 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39093363

Assessment of an Airway Curriculum in a Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellowship Program.

ATS Sch, 5(3):420-432, 15 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39371227 | PMCID: PMC11448942

Noninvasive Ventilation for Preoxygenation during Emergency Intubation.

N Engl J Med, 390(23):2165-2177, 13 Jun 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38869091

Efficacy of bougie first approach for endotracheal intubation with video laryngoscopy during continuous chest compression: a randomized crossover manikin trial.

BMC Anesthesiol, 24(1):181, 21 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38773386 | PMCID: PMC11106944

Go to all (20) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Clinical Trials

- (1 citation) ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT03928925

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Effect of Use of a Bougie vs Endotracheal Tube and Stylet on First-Attempt Intubation Success Among Patients With Difficult Airways Undergoing Emergency Intubation: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

JAMA, 319(21):2179-2189, 01 Jun 2018

Cited by: 81 articles | PMID: 29800096 | PMCID: PMC6134434

BOugie or stylet in patients UnderGoing Intubation Emergently (BOUGIE): protocol and statistical analysis plan for a randomised clinical trial.

BMJ Open, 11(5):e047790, 25 May 2021

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 34035106 | PMCID: PMC8154972

Effect of endotracheal tube plus stylet versus endotracheal tube alone on successful first-attempt tracheal intubation among critically ill patients: the multicentre randomised STYLETO study protocol.

BMJ Open, 10(10):e036718, 07 Oct 2020

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 33033014 | PMCID: PMC7542923

Orotracheal intubation in infants performed with a stylet versus without a stylet.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 6:CD011791, 22 Jun 2017

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 28640930 | PMCID: PMC6481391

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCATS NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: UL1 TR000445

NCRR NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: UL1 RR024975

NHLBI NIH HHS (5)

Grant ID: K23 HL143053

Grant ID: K23 HL153584

Grant ID: T32 HL105346

Grant ID: K12 HL133117

Grant ID: K08 HL148514

1

1