Abstract

Introduction

Patients with glomerular disease experience symptoms that impair their physical and mental health while managing their treatments, diet, appointments and monitoring general and specific indicators of health and their illness. We sought to describe the perspectives of patients and their care partners on self-management in glomerular disease.Methods

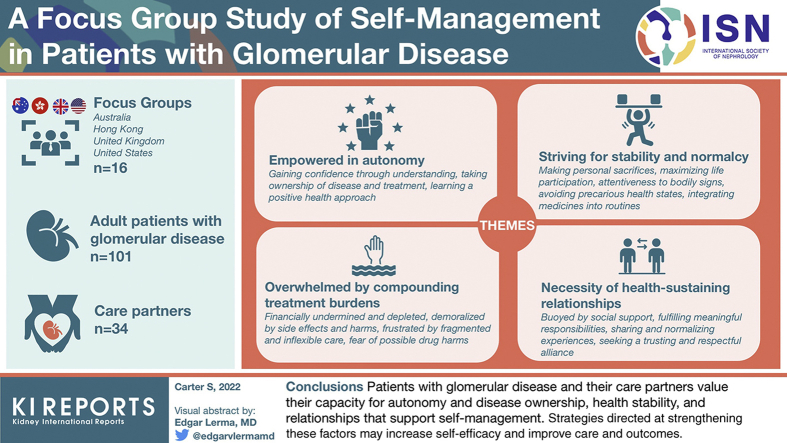

We conducted 16 focus groups involving adult patients with glomerular disease (n = 101) and their care partners (n = 34) in Australia, Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, and United States. Transcripts were analyzed thematically.Results

We identified the following 4 themes: empowered in autonomy (gaining confidence through understanding, taking ownership of disease and treatment, learning a positive health approach); overwhelmed by compounding treatment burdens (financially undermined and depleted, demoralized by side effects and harms, frustrated by fragmented and inflexible care, fear of possible drug harms); striving for stability and normalcy (making personal sacrifices, maximizing life participation, attentiveness to bodily signs, avoiding precarious health states, integrating medicines into routines); and necessity of health-sustaining relationships (buoyed by social support, fulfilling meaningful responsibilities, sharing and normalizing experiences, seeking a trusting and respectful alliance).Conclusion

Patients with glomerular disease and their care partners value their capacity for autonomy and disease ownership, stability of their health, and relationships that support self-management. Strategies directed at strengthening these factors may increase self-efficacy and improve the care and outcomes for patients with glomerular disease.Free full text

A Focus Group Study of Self-Management in Patients With Glomerular Disease

Abstract

Introduction

Patients with glomerular disease experience symptoms that impair their physical and mental health while managing their treatments, diet, appointments and monitoring general and specific indicators of health and their illness. We sought to describe the perspectives of patients and their care partners on self-management in glomerular disease.

Methods

We conducted 16 focus groups involving adult patients with glomerular disease (n = 101) and their care partners (n = 34) in Australia, Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, and United States. Transcripts were analyzed thematically.

Results

We identified the following 4 themes: empowered in autonomy (gaining confidence through understanding, taking ownership of disease and treatment, learning a positive health approach); overwhelmed by compounding treatment burdens (financially undermined and depleted, demoralized by side effects and harms, frustrated by fragmented and inflexible care, fear of possible drug harms); striving for stability and normalcy (making personal sacrifices, maximizing life participation, attentiveness to bodily signs, avoiding precarious health states, integrating medicines into routines); and necessity of health-sustaining relationships (buoyed by social support, fulfilling meaningful responsibilities, sharing and normalizing experiences, seeking a trusting and respectful alliance).

Conclusion

Patients with glomerular disease and their care partners value their capacity for autonomy and disease ownership, stability of their health, and relationships that support self-management. Strategies directed at strengthening these factors may increase self-efficacy and improve the care and outcomes for patients with glomerular disease.

Glomerular diseases can be unpredictable, create uncertainty, and impair patients’ abilities to function normally, which present challenges to patients and care partners when managing their health. These diseases are chronic and have ongoing impacts across different life stages, including teenagers transitioning to adult care, the working and reproductive years, and in later life with attendant comorbidities. Patients with glomerular disease may experience unpleasant and debilitating symptoms, including swelling, fatigue, changes in their physical appearance, and cognitive impairment.1, 2, 3 They have increased risks of cardiovascular disease, kidney failure needing dialysis or transplant, and premature death. Furthermore, they are at risk of developing serious adverse treatment-related effects, including infection and cancer.10, 11, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 These impacts are often distressing and disruptive to patients and families, limit planning, impair physical or mental functioning, and worsen quality of life.12, 13, 14, 15, 16

Self-management is defined as the ability to manage the symptoms, treatments, lifestyle changes, and financial and psychosocial consequences of a condition.17 Together with shared decision-making, it forms the foundation of person-centered care and follows the “democratization of healthcare.”18, 19, 20 First proposed over 50 years ago, the field of self-management now includes numerous theoretical frameworks and descriptions of the processes entailed as they relate to health in chronic disease.21, 22, 23 There are an increasing number of self-management support programs and interventions for chronic conditions (including in chronic kidney disease), with strategies potentially pertinent to patients with glomerular disease.24, 25, 26, 27, 28 In addition to self-management tasks required in any chronic condition, patients with glomerular disease may need to learn modifiable factors that exacerbate or precipitate their disease (e.g., relapse triggers, salt and protein intake), medication actions and safety (e.g., infection, corticosteroid toxicity), the importance of monitoring (e.g., urine protein, blood tests), preventative health care (e.g., bone health, optimizing cardiovascular risk factors), and indicators on how and when to seek medical attention.29

There is limited evidence describing or addressing patient perspectives toward self-management in glomerular diseases. Understanding the many challenges in accessing information, instituting treatments and monitoring, and the impacts of prognostic uncertainty for those living with glomerular disease may identify ways to better support patient management. The aim of this study is to describe the motivations, barriers, and attitudes toward self-management in patients with glomerular disease and their care partners. We also sought to explore patient and care partner perspectives on their access to health information used in self-management.

Methods

The data reported in this study were collected as part of the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology–Glomerular Disease Initiative, which have not been previously analyzed or published. We reported our study according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies framework.30

Participant Selection

Patients with glomerular disease and their care partners were purposively sampled from 3 centers in Australia (Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane), 4 centers in Hong Kong, 3 centers in the United Kingdom (York, Sheffield, and London), and 1 center in the United States (Los Angeles), to capture a range of demographic and clinical characteristics. Care partners were invited to elicit more distal impacts and implications of patient-related care needs. All care partners were those assisting patients in self-management tasks, including accessing health services, supporting role functioning, and mental health support. Participants spoke English or Spanish.

Patients were identified by their treating nephrologist as eligible for inclusion if they were aged >18 years and had the following glomerular diseases: IgA nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, complement-mediated glomerulopathy, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (unspecified), lupus nephritis, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis (AAV), IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schoenlein purpura), or antiglomerular basement membrane disease. Patients with glomerular diseases who have a substantially different clinical course (e.g., postinfectious glomerulonephritis), disease manifestations (e.g., Alport disease, diabetic nephropathy), or treatment (e.g., hepatitis and HIV-associated disease) were excluded.31 Participants were approached by phone and e-mail; all participants gave written informed consent and received reimbursement of costs incurred owing to participation in this study of US$ 50 or the equivalent in local currency. Ethics approval was obtained for all participating sites (Supplementary Item S1).

Data Collection

Two-hour focus groups were conducted in meeting rooms external to clinical settings from March 2018 to July 2018. One investigator (AT, LR, SAC, TG) moderated the groups while a second investigator (CL, LD, SAC, TG) took field notes of participant dynamics and nonverbal communication. The question guide was developed based on existing literature and discussion among the research team (Supplementary Item S2).32,33 All group discussions were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. Focus groups were convened until data saturation, that is, when no new themes were identified.

Analysis

Transcripts were entered into HyperRESEARCH software (ResearchWare, Inc., Randolph, MA; version 4.0.1) for qualitative data analysis. Using thematic analysis and principles from grounded theory,34 CT conducted line-by-line coding of the transcripts and inductively identified concepts related to motivators, barriers, and attitudes to self-management. Preliminary themes were discussed and revised with SAC and AT, who had independently read the transcripts, to ensure that the full breadth and depth of the data were captured in the analysis. We identified conceptual patterns and links among the themes to develop a thematic schema.

Results

We conducted 16 focus groups with 134 participants, of whom 101 (75%) were patients and 33 (25%) were care partners. Demographic and clinical characteristics are found in Table 1. Reasons for nonparticipation were work commitments, being unwell, and lack of interest. Though all care partners were invited, fewer care partners than patients attended the groups. Participants ranged from 19 to 85 years old (mean 51 years). There were 66 males (49%) and 61 Whites (46%). Patients with diverse glomerular diseases were included, the 3 most common being lupus nephritis (n = 18), vasculitis (n = 18), and IgA nephropathy (n = 18). Patients’ care was based in hospital outpatient departments. Time since diagnosis ranged from 0 to 52 years, with a median of 6 years, and patients were diagnosed at a mean age of 39 years (range 2–85 years). Most patients (n = 66, 65%) had not received dialysis or transplant.

Table 1

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics

| Participant characteristics | All |

|---|---|

| N = 134 (%) | |

| Country | |

| Australia | 50 (37) |

| Hong Kong | 22 (16) |

| United Kingdom | 29 (22) |

| United States | 33 (25) |

| Patient | 101 (75) |

| Care partner or family member | 33 (25) |

| Self-identified gender | |

| Male | 66 (49) |

| Female | 68 (51) |

| Age group (yr) | 32 (24) |

| 18–39 | 57 (43) |

| 40–59 | 42 (32) |

| 60–79 | 2 (2) |

| >80 | |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 61 (46) |

| Asian (Central, South, East) | 38 (28) |

| Hispanic | 23 (17) |

| African/African American | 6 (4) |

| Other | 6 (4) |

| Educational attainmenta | |

| Primary school | 21 (21) |

| Secondary school (grade 10) | 26 (26) |

| Certificate/diploma | 22 (22) |

| University degree | 30 (30) |

| Employmenta | |

| Full time or part time | 40 (40) |

| Student | 4 (4) |

| Not employed | 21 (21) |

| Other/retired | 34 (34) |

| Income (USD)a | |

| <60,000 | 73 (73) |

| 60,000–150,000 | 8 (8) |

| >150,000 | 2 (2) |

| Not stated | 18 (18) |

| Type of glomerular diseasea | |

| Lupus nephritis | 18 (18) |

| ANCA-associated vasculitis | 18 (18) |

| IgA nephropathy | 18 (18) |

| Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | 10 (10) |

| Membranous nephropathy | 6 (6) |

| Minimal change nephropathy | 5 (5) |

| Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis | 6 (6) |

| C3 glomerulopathy | 5 (5) |

| Antiglomerular basement membrane disease | 1 (1) |

| IgG4-related disease | 1 (1) |

| Years since diagnosisa | |

| ≤2 | 30 (30) |

| 3–11 | 31 (31) |

| ≥12 | 34 (34) |

| Treatment stage of kidney diseasea | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 66 (65) |

| Hemodialysis | 14 (14) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 13 (13) |

| Kidney transplant | 15 (15) |

| Comorbid conditionsa | |

| Diabetes | 18 (18) |

| Depression/anxiety | 16 (16) |

| Obesity | 14 (14) |

| Cardiovascular disease including stroke | 11 (11) |

| Asthma | 9 (9) |

| Cancer | 6 (6) |

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; USD, United States dollar.

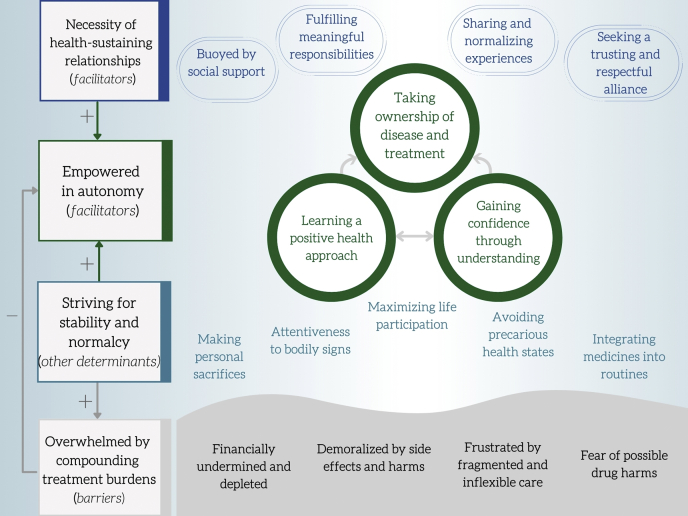

There were 4 themes identified. Empowered in autonomy and necessity of health-sustaining relationships described facilitators of self-management, whereas overwhelmed by compounding treatment burdens captured key barriers. Striving for stability and normalcy outlined additional key determinants of self-management in patients with glomerular disease. Themes and subthemes are described subsequently with illustrative quotations found in Table 2. Supplementary Table S1 reveals the distribution of identified themes by country, age group, type of disease, and disease stage. The thematic schema in Figure 1 illustrates how the themes and subthemes relate to each other.

Table 2

Selected illustrative quotations for themes and subthemes

| Empowered in autonomy | |

| Gaining confidence through understanding | You have to be informed. You have to know what’s happening to you and how it’s happening to you.—Patient, United States It’s about having the information to empower you to make those choices.—Patient, United Kingdom Uncertainty. It was back then, but now I’m a bit, I’ve been attending the seminars, seeing the doctor, so I feel a bit confident.—Patient, Australia |

| Taking ownership of disease and treatment | I love that feeling of actually looking for the areas that I can control, because it makes me think I’m contributing something to this in a positive way.—Patient, Australia The medication, you got to pay attention to it. Your lab appointments, blood work … at the end of the day you become your own doctor.—Patient, United States [Self] management can go a long way, and not just relying on the health care system. They do a great job, but it’s ultimately our body and you’ve got to try and fight for it.—Patient, United Kingdom |

| Learning a positive health approach | One thing you said that was really important is your personal mental attitude toward this. If you come out thinking you’ve had some disaster happen to you, or woe me because my life is now changed, you’re going to wither away. You have to come out positive, because it’s as much about the health, rejuvenation, than anything to do with putting the kidney in your body.—Patient, United Kingdom I think I have a lot of self-control and [perform] self-monitoring. Just trying to live a healthy lifestyle can play a massive role in how well you can live your life so far.—Patient, United Kingdom |

| Overwhelmed by compounding treatment burdens | |

| Financially undermined and depleted | The cost of the medication, that’s a killer, it goes from $6 to $39, and literally you can’t go back to work, you know?—Patient, Australia I want to go back to work, but a lot of jobs are not trying to hire me because of so many symptoms I have … It’s kind of stressful and it’s kind of depressing.—Patient, United States |

| Demoralized by side effects and harms | Those immunosuppressant drugs are giving me hell. In the last five or more, six to eight years, I’ve been in that hospital about 20 times because of infections. Bladder infections, lung infections, throat infections, ear infections. The last one, that nearly killed me.—Patient, Australia It was hard. I did eight rounds of plasma exchange. Twelve rounds of IV chemo and six rounds of oral chemo. I gained 90 pounds in steroid weight, I gained 19 pounds in two days and not eaten anything. It was horrible.—Patient, United States |

| Frustrated by fragmented and inflexible care | I go to a few different clinics—they tend to focus on that particular problem…It may be disastrous for some, for another problem you’ve got.—Patient, United States I think relentless appointments … Out of that month, it’s probably another four, five appointments. It’s always the doctors will only work on one specific day, so I’ve been in to see the nephrologist, and the next day I go to work, and then I’ve got to cancel work the day after that.—Patient, Australia |

| Fear of possible drug harms | You do wonder sometimes, the amount of chemicals you’re putting in your body. That can’t be good. It’s probably helping. But what else is it doing?—Patient, Australia What is it going to do? Because it may do something to somebody else, and it’ll do something different to you.—Patient, Australia |

| Striving for stability and normalcy | |

| Making personal sacrifices | [I’m] really sad because I would like to have more kids, but they don’t allow me anymore. I could, but it’s a risk—Patient, United States My friends have gotten used to me saying yeah, you’re not coming over because you’re sick. Just stay away, and especially young children. Sorry, please stay away. I’ve had to do that just to look after myself.—Patient, Australia |

| Maximizing life participation | To be honest, for people who [get to] this stage [of kidney disease], it’s more like you will try your very best to live your life, to do whatever you want when it’s still available.—Patient, Hong Kong Whether you’re sick or you’re healthy … what you want now is to be able to live the quality of life and be able to participate in life.—Patient, Australia My daughter is five … it brought into perspective what I wanted out of my life. Put those at the top of my priorities and made sure that I spend as much time on that.—Patient, Australia |

| Attentiveness to bodily signs | So you don’t end up with big swollen legs, because you spot the froth in urine beforehand. You see them, they treat you, you’re fixed.—Patient, United Kingdom It’s good to help you manage. If I start getting edema, things are not looking good for me. I start checking the swelling in my ankles and feet, and if I can press in, I react. I’ll react and go to the doctor.—Patient, Australia |

| Avoiding precarious health states | Everything is fine because I’m constantly taking that pill. When I wasn’t taking that pill, I was in and out of the hospital. Everything was going wrong.—Patient, United States I’m scared now … I’m worried because my potassium levels can take me back to dialysis.—Patient, United States |

| Integrating medicines into routines | When they decided to give me some extra doses of medication … I forget. I just can’t get into the habit of taking it.—Patient, Australia Having a fixed schedule or routine to take all your medication, which ones do you have to take with food, which ones with water. How you take your medication.—Patient, United States |

| Necessity of health-sustaining relationships | |

| Buoyed by social support | I’m very lucky, it’s my sister and family who support me. If I don’t have them, I will not be alive until now. Family is very, very important.—Patient, Hong Kong When I’m falling asleep after a nice dinner at somebody’s house, they just accept it … they don’t put me down for it, and I’m still here and I still have a good time, still go out.—Patient, United Kingdom |

| Fulfilling meaningful responsibilities | To be able to participate … you know, the growth of the country and yourself, and get back to work.—Patient, United Kingdom I’ve got two beautiful grandchildren who light up my world, and they just push you through every day.—Patient, United Kingdom |

| Sharing and normalizing experiences | It’s good listening to other people. I find that’s a big thing for me, I feel very alone. I don’t know many other people who have a similar disease, and I’d really like to be able to talk to other people, you know? It makes a huge difference.—Patient, Australia I want to hear from people that have gone through this themselves.—Patient, United States You don’t want to burden everybody. This sort of forum, we’re not burdening anybody.—Patient, Australia |

| Seeking a trusting and respectful alliance | I noticed the change in her outlook … I think if you’ve got confidence [in the physician], it improves your outlook to no end. Deal with somebody you can rely on and trust and have great confidence in.—Care partner, Australia You want that respect from your doctor, and you want them to discuss the research with you, and their decision making and involve you in the decision making process. There are always options, but it’s nice to know that you’ve been a part of that process in terms of what the plan forward is.—Patient, United Kingdom It means the doctors are good, because they can reassure you. If you can believe them, that means you’re able to put your trust in them.—Patient, United Kingdom |

Thematic schema relating the motivators, barriers, and attitudes to self-management in patients with glomerular disease.

Empowered in Autonomy

Gaining Confidence Through Understanding

Patients were motivated by “uncertainty,” “confusion,” and “doubt” to seek information preferentially from health providers but also diverse sources on the internet to reach “informed decisions” and “make the situation better.” Accessing timely and trustworthy information was challenging for patients, who were often “absolutely baffled” or suspicious of online sources. Patients required knowledge to achieve clarity, be at “peace” with distressing events, and “empower” themselves at a time when they felt they were surrendering control of their health.

Taking Ownership of Disease and Treatment

Some wanted more control in disease management to gain “increased certainty” on their health. Patients had a strong sense of responsibility for their health and felt that they should “try and fight for it” by seeking greater agency in treatment decision-making, home monitoring, increasing engagement with health services, and making lifestyle changes. Some felt disillusioned as they sensed patient ownership of their disease was not supported by their health care system or felt helpless because they lacked knowledge or were unable to influence their disease, thereby becoming “very passive” like a “robot” in their management.

Learning a Positive Health Approach

Some patients were overwhelmed by negative language and information because they were “always told the bad news,” which undermined their sense of “hopefulness or success” and perceived the goal of care as “trying to hold things where they are.” Thus, they strived to be proactive and “productive” by focusing on things that they could “do something about” (e.g., medication adherence, monitoring, and diet) and adopted a “positive outlook” by focusing on managing their sleep and anxiety, rather than feeling burdened by health events outside their control (e.g., death, hospitalization, relapses).

Overwhelmed by Compounding Treatment Burdens

Demoralized by Side Effects and Harms

Patients “put up” with side effects because they were perceived as transient or there was no better alternative to prevent “damage to your kidneys,” but other patients felt traumatized by “horrible” side effects that made them question the benefit of continuing treatment (e.g., corticosteroids, dialysis). Recurrent side effects engendered a negative “state of mind” and “robs” patients of their quality of life.

Fear of Possible Drug Harms

Some patients expressed doubts on medications because they “don’t know what it’s doing” or might have “different impacts on different people,” or they were concerned on drug interactions. Other patients expressed outright fear of “poisonous” immunosuppressive treatments because they felt “more susceptible” as their “body is disarmed.”

Financially Undermined and Depleted

Medications, tests, time off work, and insurance cost an “absolute fortune” for some families and caused guilt for the patient who wished they “could do more” by earning money or paying for medicines. Symptoms of glomerular disease (e.g., fatigue) or being a “liability” to companies meant some patients lost their job or could not secure employment, which was “stressful and depressing” as they were unable to pay rent or buy food for their families.

Frustrated by Fragmented and Inflexible Care

Patients often felt “let down” by health systems that did not “make it easy” to obtain timely information and treatments for their glomerular disease and felt anxious “waiting” for updates on their largely asymptomatic kidney health and disease status (e.g., urine protein, estimated glomerular filtration rate). After a “bad result,” accessing health care was stressful and disruptive owing to “juggling … relentless appointments.” Some specialist health providers addressed a narrow set of issues that meant additional appointments or made changes that lead to negative impacts in other areas of the patient’s health.

Striving for Stability and Normalcy

Attentiveness to Bodily Signs

Some patients used their “body as a marker” or “indicator” to detect changes in their health state (e.g., frothy urine and swelling) and determined if action was needed. For example, patients learned to “recognize the signs” and “check for swelling” signifying fluid overload or “see the [urinary] bubbles” of heavy proteinuria. This increased their agency and sense of control, because they could react, seek treatment, and avoid complications.

Avoiding Precarious Health States

Patients recognized that relapse, infection, need for dialysis, and cancer represented “silent surprises” that increased “uncertainty about what the future holds.” Patients tried to avoid the “constant roller coaster” because it was “scary as hell” and “anything could happen.” Ultimately, they sought “predictability” because it reduced anxiety and enabled actions that further stabilized and optimized their health, such as engaging in preventative health measures (e.g., avoiding “triggers” of “flare ups”), achieving financial security, and life participation.

Maximizing Life Participation

Patients felt that their disease was “killing” them through a “very restrictive life” but fought to “continue to experience” and “enjoy life” because those meaningful and fulfilling events (i.e., hobbies, work, travel, and family time) helped sustained them. Adverse health outcomes sometimes helped patients prioritize “what [they] wanted” and focused them on making the most of the “valuable time you’ve got.” This entailed maintaining stable health, financial independence, and a regular health care schedule (e.g., appointments) that minimized the impact on being “able to live” and strengthened their ability to “contribute” and be “productive.”

Making Personal Sacrifices

Patients felt that consequences of their disease or treatment often meant making “restrictive” decisions “just to look after [themselves].” These included symptoms that “took a toll” (e.g., fatigue and giving up work), time and money required for health care limiting social activities, or sacrifices to reduce health risks (e.g., delaying or preventing pregnancy, travel, sun exposure). Some patients were forced to accept threats to their fertility (e.g., subfertility, infertility, teratogenicity). These were often deliberate actions and “a compromise” to help maintain the “status quo.”

Integrating Medicines Into Routines

Some were reluctant to take medication, forgot, or were dismayed by the number of tablets and had to learn “how to take medication” and “juggle everything around.” They recognized the importance of a “routine” or “fixed schedule” supported by weekly medication packs so that they could take their medications consistently. Some could “feel the difference” when taking their medication consistently or recognized they “can’t skip dosages,” whereas prescription changes caused frustration as patients had trouble “getting into the habit of taking it.”

Necessity of Health-Sustaining Relationships

Buoyed by Social Support

Family and friends provided essential physical and emotional support (e.g., arranging and attending appointments with patients, financial planning, sharing home duties); patients knew that they could “fall back on” them and advocate for their health when it was “too much to process.” Feeling isolated by a disease “no one can see” was “one of the hardest things,” and though friends and family could provide support, patients often felt that they did not “really understand.” Patients felt guilty because “people around us suffer too,” and they did not “want to burden other people.”

Sharing and Normalizing Experiences

Patients found that it was “important not to feel alone” and that sharing experiences and “similar stories” (e.g., the silent impact of fatigue, distressing effects of corticosteroids) was very uplifting because they could “see what other people are going through” and “learn a lot.” They felt understood and could support each other because they “know where I’m coming from” and felt that they were “not burdening anybody,” unlike with friends or family.

Fulfilling Meaningful Responsibilities

Some patients felt motivated to self-educate, optimize their health, and “prepare for the worst” out of fear for their children’s well-being or other family members, who were involved or affected by their disease. Nevertheless, they also desired to be a “contributing part” of their family and society, to avoid being a “burden,” and to care for and “be present for [children] as they grow up.” Patients who maintained their kidney health by avoiding pregnancy or taking alkylating agents felt grief from potentially foregoing parenthood.

Seeking a Trusting and Respectful Alliance

A positive, health-focused patient-physician relationship was a “lifesaver” in enabling patients in their own care. Professional competence allowed patients to “trust” and “rely on the expertise,” but the relationship conferred other psychological benefits, such as the ability to better reassure and having “complete confidence” when an emotional connection also existed and the patient sensed the physician “really cares.” Patients valued and sought a bidirectional “help them [to] help me” exchange of information where the patient felt listened to, informed, and “involved … in the decision-making process,” using a respectful communication style that moved the patient in a “positive direction.”

Discussion

The patients with glomerular disease in this study wanted more control over their health care and were generally motivated to better understand their condition, avoid unstable health states such as relapse or infection, monitor their signs and symptoms, and make proactive changes for health benefits. They monitored their health and tried to stabilize or predict changes in their health in an endeavor to modify the disease course, achieve a sense of certainty, and enable forward planning. Glomerular diseases and treatments threatened patients’ autonomy by impairing psychological, cognitive, social, or financial health and could overwhelm their ability to engage in self-management. Therapeutic relationships with health professionals, family, friends, and other patients were key enablers of self-management (e.g., acquiring knowledge, medications, attending appointments), helped to stabilize mental and social health, and supported autonomy during ill health and escalation of treatment (e.g., fluid overload, dialysis, relapse). A multidisciplinary care team is needed to support patients’ self-care needs as they can be complex, resource intensive, and difficult to address in routine outpatient consultations.

The 4 themes were identified within and important to all participant countries, age groups, types of glomerular disease included, and stages of kidney disease. Nevertheless, some differences were noted among patients with different disease phenotypes. Patients with relapsing-remitting diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, AAV, minimal change disease) were more invested in avoiding precarious health states owing to relapse or infection, minimizing difficult-to-treat harms such as infertility or cancer, and attentiveness to bodily signs as a means of predicting or avoiding future events. These features were also relevant to those with progressive disease, poor kidney function, or receiving immunosuppression (e.g., avoiding hyperkalemia, unexpected hospitalization). Patients with slowly progressive diseases (e.g., IgA nephropathy) often felt incapable of influencing their underlying disease course, so they focused on modifiable lifestyle measures, whereas those with relapsing-remitting conditions felt uncertain or anxious owing to constantly seeking a balance between side effects and disease stability. Older patients and patients with life- or organ-threatening disease (e.g., AAV) expressed concerns on limitations to their independence, causing them to focus on fulfilling meaningful responsibilities (e.g., caring for children, contributing financially) and maximizing life participation.

Patients with glomerular diseases face specific self-management tasks and challenges to achieve confidence and ownership in managing their disease when compared with patients with other causes of chronic kidney disease.29,32 These arise from difficulty accessing trustworthy information, an often silent and unpredictable disease course, and a complicated and evolving understanding of disease mechanisms with changing terminology. Patients not receiving kidney replacement therapy experienced considerable doubt on their future kidney health and disease stability that they minimized by increasing their understanding, tracking response to medication, improving treatment concordance, and reducing their exposure to risk (e.g., dietary, infectious, metabolic stressors). Some patients felt that their disease and treatment threatened their reproductive autonomy—particularly women facing pregnancy-related risks—which they had to confront and navigate to better manage their health. Difficulty connecting with other patients with similar experiences (e.g., owing to rare disease, no patient support group) left patients feeling isolated, poorly understood, and diminished in their capacity for self-management. Patients and care partners require a tailored approach that targets their specific learning and skill needs. This may include establishing a set of expectations regarding their disease course and methods of evaluating both disease activity and progression of irreversible kidney damage.

Many self-management strategies for other chronic conditions exist, and these may be adapted for patients with glomerular disease. Patients with some glomerular diseases could benefit from an individualized needs assessment and learning curriculum, similar to that used in patients with diabetes.25,35 Education and self-monitoring in adults with asthma (e.g., peak expiratory flow rates) reduce unnecessary access of health care resources and improve health outcomes, including quality of life.36,37 Avoiding triggers of disease is a common preventative approach in people with glomerular disease and other chronic conditions (e.g., in allergy, asthma, epilepsy) and can improve disease control,38 though evidence supporting this approach is often lacking. Peer support is valuable to patients with many chronic conditions,39, 40, 41 which may also be relevant for developing peer-led interventions in glomerular disease.24,42 Patients with head and neck cancer fostering a positive health outlook have a better quality of life and lower fear of recurrence.43 At the health systems level, policy makers should consider existing frameworks that support self-management at multiple levels by providing patients and health professionals with resources, education, and training; encourage awareness and culture change; and increase access to health providers and services.44 Importantly, patient education and disease ownership are foundational to these strategies.

We sought novel perspectives relevant to patient self-management from diverse participants with glomerular disease and their care partners internationally. Groups were conducted in either English or Spanish language. Nevertheless, there were potential limitations. Participants were recruited from 4 high-income, resource-rich countries with ready access to kidney replacement therapy, and so the transferability of our findings to other cultural settings and populations is uncertain. Participants in the focus groups may have tended to be more engaged in research and have higher health literacy. Though we included a large number of patients with prevalent glomerular conditions from 4 countries, the perspectives of patients with rarer types of glomerular disease may not have been adequately captured. We used 4 experienced moderators (3 women, 1 man); however, confirmation and social desirability bias may have influenced the findings.

Self-monitoring skills and avoiding exposures to infectious risks or disease triggers are key tasks for many patients with glomerular disease (see suggestions for clinical practice in Table 3). Monitoring for swelling, changes in weight or urine protein on dipstick in response to treatment, or other signs of relapse are practiced by patients with nephrotic disease in some health systems; however, teaching these skills is often not explicitly recommended in guidelines for these diseases.45 Similarly, teaching patients on how to minimize serious infectious risks after treatment (e.g., being up to date with specific immunizations, postexposure prophylaxis)45, 46, 47 and disease triggers (e.g., sun exposure)48 is a strategy that may be instituted for patients with conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus or for those taking immune suppressants. We believe and it has been suggested that patient education to achieve these skills can improve health outcomes49,50 and increase patient confidence and their ability to affect change (e.g., preventing exposure to risk, responding earlier to signs and symptoms).17,28

Table 3

Self-management strategies and suggestions for patients with glomerular disease

| Strategy domain | Suggestions to support self-management |

|---|---|

| Increase patients’ knowledge | Provide access to consistent and trustworthy information Give personalized information on the disease and treatments Deliver face to face at an appropriate health literacy level with a support person; account for learning barriers (e.g., hearing or visual loss) Address lifestyle modifications important in glomerular disease (e.g., salt intake, aerobic activity) Inform of risks owing to infection and sun exposure |

| Support shared decision-making | Ensure health professionals are trained in shared decision-making and communication skills Elicit patients’ perspectives and goals before exploring relevant treatment options Use a decision-support tool (e.g., IgAN, dialysis, immunosuppression) Pre-emptively discuss fertility, pregnancy, and family planning |

| Address medication safety | Preventative approaches to side effects (e.g., vaccination, calcium intake, weight bearing, and bone density checks) Raise awareness of nephrotoxins, teratogenicity (e.g., renin-angiotensin-aldosterone blockade, mycophenolate) and drug-drug interactions (e.g., calcineurin inhibitors) |

| Provide new skills | Home monitoring for urinary protein, weight, and blood pressure, where appropriate and with support Teach patients on how to check for swelling and action plan |

| Increase prioritization among health professionals | Teach self-management frameworks in training programs Promote training patients in self-management Include self-management recommendations in clinical practice guidelines Increase remote accessibility to the managing team |

| Provide psychosocial support | Provide regular health-facing updates and avoid a “deficit discourse” Support patient access to peer support groups and organizations Pre-emptively identify and normalize the need for mental health supports |

Suggestions were derived from focus group participants, current practice, and the literature.

Our study also highlights the importance of supporting patients’ understanding of the trade-offs between disease-induced morbidity and the adverse effects of treatments in glomerular disease (Table 3). Together with patients, health professionals should acknowledge, share responsibility for, and repeatedly reassess the balance of harms in treatment decisions, as some serious risks may not be immediately apparent or reversible (e.g., infertility, osteoporosis, malignancy).51, 52, 53 Unanticipated or distressing side effects (e.g., Cushingoid appearance, diabetes mellitus) may fracture the therapeutic relationship and reduce treatment adherence contributing to adverse outcomes. This is particularly relevant when patients with few or no symptoms of disease experience treatment-related adverse events in situations where treatment benefits are only realized in the longer term (e.g., early chronic kidney disease or remitted disease). A trusting therapeutic relationship can facilitate complex decision-making and give patients greater certainty and confidence in managing their health. Decision aids and risk-prediction models are tools that can reduce decisional conflict by clarifying therapeutic options that align with patients’ priorities or better quantifying anticipated benefits (e.g., immunosuppression in lupus nephritis, risk-prediction tool in IgA nephropathy).54, 55, 56

Future research should focus on co-developing self-management interventions with patients based on these key areas, demonstrating their efficacy in trials and then delivering them as part of routine care (Table 4). Existing self-management interventions are largely focused on diet or lifestyle in chronic kidney disease, developed without patient input and lack a theoretical framework.50,57 Potential interventions for trials in glomerular disease could target increasing patient disease knowledge, improving the quality of shared decision-making (e.g., decision aids, risk-prediction models), and instituting home disease monitoring or a self-management “toolkit” comprising a suite of strategies.28 Trials should evaluate not only the impact of self-management interventions on outcomes of importance to patients with glomerular disease such as kidney function, life participation, and mental health but also cost-effectiveness.58,59

Table 4

Remaining gaps and research priorities for self-management in patients with glomerular disease

| Area of study | Future research questions and aims |

|---|---|

| Identify existing and novel self-management strategies | Identify all relevant existing self-management strategies for patients with glomerular disease from another chronic condition(s)44 Are there novel, disease-specific self-management strategies that could be proposed by patients, care partners, and health professionals? |

| Target population | Which interventions are specific to one type of glomerular disease? Which strategies are relevant across all patients with chronic kidney disease? Identify those interventions or strategies that are equally important and those that are different across various resource settings, health literacy, rural populations |

| Identify priorities | Establish a candidate set of self-management strategies (to inform their development) with patients, care partners, and health professionals Use an existing theory (i.e., behavioral change theory) to better inform the candidate set of prioritized strategies |

| Co-design interventions | Codesign self-management interventions (individual or bundled) with all stakeholders, including patients, using an appropriate theory Use existing self-management interventions with demonstrated effectiveness in other conditions to inform those in patients with glomerular disease |

| Efficacy and cost-effectiveness | Do self-management programs improve health outcomes or delivery of patient care? Are self-management interventions cost effective in chronic glomerular disease? |

| Co-implementation | What are the provider-level barriers and facilitators to implementation? What are the health system determinants of implementation? What is the optimal framework(s) that supports self-management in patients with glomerular disease at multiple levels? |

Empowered in autonomy, striving for stability and normalcy, necessity of health-sustaining relationships, and overwhelmed by compounding treatment burdens were identified as the major self-management themes for patients with glomerular disease. Several self-management challenges and strategies are unique to glomerular disease, and current approaches to supporting self-management in patients with glomerular disease are undervalued, limited in scope, and under-resourced.20 Self-management is critical for patients with glomerular disease, and this should be reflected by recommendations in guiding policy documents, clinical practice guidelines, and research priorities.

Disclosure

DJ reports receiving consultancy fees, research grants, speaker’s honoraria, and travel sponsorships from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care; consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, and AWAK; speaker’s honoraria and travel sponsorships from ONO; and travel sponsorships from Amgen. LL reports receiving consultancy fees from Alexion, Aurinia, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer and speaker’s honoraria and travel sponsorships from Achillion, Alexion, and GlaxoSmithKline. MW reports receiving consultancy fees and honoraria from Baxter and advises Triomed AB. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients and their care partners who generously gave their time and shared their experiences during this study. This project is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Program Grant (1092957). SAC is supported by the NHMRC Postgraduate Scholarship (1168994). DJC is supported by grant K08DK102542 from the National Institutes of Health. YC is supported by the NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (1126256). TG is supported by a NHMRC Postgraduate Scholarship (1169149). DJ is supported by a NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (1117534). JIS is supported by grant K23DK103972 from the National Institutes of Health. ATP is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1106716). AKV received grant support from the NHMRC Medical Postgraduate Scholarship (1114539). NSR is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Postgraduate Scholarship (1190850). The funding bodies did not have a role in the design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The remaining authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Author Contributions

Research idea and study design: SAC, TG, DC, LL, AB, SJB, JBa, JBo, DJC, RC, FCC, JF, MAH, JJH, ARK, RAL, AMal, JRa, BHR, NSR, HT, HZ, YC, AKV, JIS, AYMW, ATP, JCC, AT; data acquisition: SAC, TG, CL, KA, YC, AKV, LD, DH, DWJ, PGK, PL, JRy, JIS, LR, AYMW, AHKL, SFKS, MKHT, MW, AT; data analysis/interpretation: SAC, CT, TG, AMar, AT; supervision or mentorship: DC, LL, AB, SJB, JBa, JBo, DJC, RC, FCC, JF, MAH, JJH, ARK, RAL, AMal, JRa, BHR, NSR, HT, HZ, ATP, SIA, JCC, AT. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Item S1. Participating sites and institutional review boards.

Item S2. Question guide.

Table S1. Distribution of the identified themes by country, age group, stage of kidney disease, and type of glomerular disease.

STROBE Statement.

Supplementary Material

Item S1. Participating sites and institutional review boards.

Item S2. Question guide.

Table S1. Distribution of the identified themes by country, age group, stage of kidney disease, and type of glomerular disease.

References

Articles from Kidney International Reports are provided here courtesy of Elsevier

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/116367305

Article citations

Living with Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome in the Netherlands: Patient and Family Perspective.

Kidney Int Rep, 9(7):2189-2197, 27 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39081735 | PMCID: PMC11284443

Qualitative Analyses to Amplify Patient and Care Partner Needs for Self-Management in Glomerular Disease.

Kidney Int Rep, 7(1):13-14, 30 Nov 2021

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 35005309 | PMCID: PMC8720811

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Promoting and supporting self-management for adults living in the community with physical chronic illness: A systematic review of the effectiveness and meaningfulness of the patient-practitioner encounter.

JBI Libr Syst Rev, 7(13):492-582, 01 Jan 2009

Cited by: 54 articles | PMID: 27819974

Patient and Caregiver Perspectives on Terms Used to Describe Kidney Health.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 15(7):937-948, 25 Jun 2020

Cited by: 23 articles | PMID: 32586923 | PMCID: PMC7341768

Patients' Perspectives on Shared Decision-Making About Medications in Psoriatic Arthritis: An Interview Study.

Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 74(12):2066-2075, 24 Aug 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 34235887

Family and health-care professionals managing medicines for patients with serious and terminal illness at home: a qualitative study

NIHR Journals Library, Southampton (UK), 20 Aug 2021

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 34410684

ReviewBooks & documents Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIDDK NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: K23 DK103972

Grant ID: R01 DK126777

Grant ID: K08 DK102542

National Health and Medical Research Council (10)

Grant ID: 1169149

Grant ID: 1092957

Grant ID: 1126256

Grant ID: K08DK102542

Grant ID: 1190850

Grant ID: 1117534

Grant ID: 1168994

Grant ID: 1114539

Grant ID: K23DK103972

Grant ID: 1106716