Abstract

Free full text

A multi-tasking stomach: functional coexistence of acid–peptic digestion and defensive body inflation in three distantly related vertebrate lineages

Abstract

Puffer and porcupine fishes (families Diodontidae and Tetraodontidae, order Tetradontiformes) are known for their extraordinary ability to triple their body size by swallowing and retaining large amounts of seawater in their accommodating stomachs. This inflation mechanism provides a defence to predation; however, it is associated with the secondary loss of the stomach's digestive function. Ingestion of alkaline seawater during inflation would make acidification inefficient (a potential driver for the loss of gastric digestion), paralleled by the loss of acid–peptic genes. We tested the hypothesis of stomach inflation as a driver for the convergent evolution of stomach loss by investigating the gastric phenotype and genotype of four distantly related stomach inflating gnathostomes: sargassum fish, swellshark, bearded goby and the pygmy leatherjacket. Strikingly, unlike in the puffer/porcupine fishes, we found no evidence for the loss of stomach function in sargassum fish, swellshark and bearded goby. Only the pygmy leatherjacket (Monochanthidae, Tetraodontiformes) lacked the gastric phenotype and genotype. In conclusion, ingestion of seawater for inflation, associated with loss of gastric acid secretion, is restricted to the Tetraodontiformes and is not a selective pressure for gastric loss in other reported gastric inflating fishes.

1. Introduction

Body inflation is an antipredator defensive mechanism [1]. Examples among vertebrates include amphibians and reptiles that use lung or buccal cavity inflation [2,3], the coffinfishes (Chaunacidae) that inflate by storing a substantial volume of water in their gill chambers [4], and notably within the stomach inflating pufferfishes and porcupine fishes (Tetraodontidae and Diodontidae sister families, respectively, Tetraodontiformes), herein referred to as ‘pufferfishes', for simplicity. Pufferfishes can increase up to three times their body size by swallowing large amounts of water that is held within the stomach [5–7]. The pufferfish stomach and body are highly modified to accommodate this inflation. Most notably, the stomach wall is thin, and the mucosa is highly folded, allowing for distension during inflation. Significantly, the pufferfish stomach lacks gastric glands (GG) and secretions for acid–peptic digestion, suggesting that the digestive function of the stomach has been replaced by a defensive function [5,8].

Interestingly, stomach inflation in vertebrates is not limited to the pufferfishes (figure 1). When in danger, the sargassum fish, Histrio histrio, from the Antennariidae family of frogfishes, has also been reported to inflate by swallowing water [9,10]. This species inhabits the sargassum complex and is known for its territoriality and voracity. Additionally, two swellshark species, Cephaloscyllium ventriosum [11] and Cephaloscyllium stevensi [12], when threatened, can double in size through stomach inflation to deter predators or wedge into crevices [11]. There is also a single observation of inflation in the bearded goby (Sufflogobius bibaratus, Gobiidae), endemic to the Benguela upwelling ecosystem, [13]. Lastly, members of the Brachaluteres genus of the Monacanthidae (filefish) family (order Tetraodontiformes) are reported to be stomach inflators [10,14,15]. The filefish together with the Balistidae (triggerfishes) form a sister clade to the puffer and porcupine fishes [16]. However, it should not be assumed that the filefishes are agastric, since GG have been reported in triggerfishes [17,18].

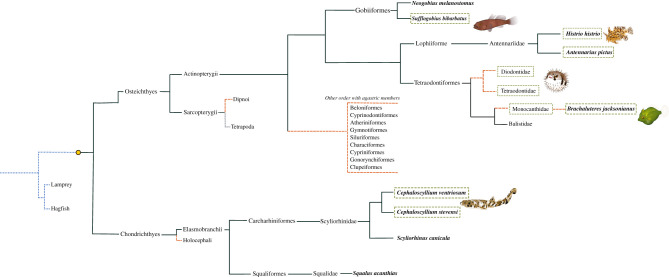

Schematic of selected fish groups having stomach acid–peptic digestion loss (yellow dashed lines) and stomach defensive inflation (dashed square), where emphasis is given to the orders of this studies' representative species. The Tetrapoda (grey dashed lines) include a single agastric clade (Monotremes). The origin of the stomach (filled circle) and ancestral agastric condition (blue dashed lines) are also indicated.

GG secrete gastric juices containing hydrochloric acid (HCl) and pepsinogens through parietal and chief cells, respectively, in mammals, and solely via oxynticopeptic cells in the other vertebrates [19]. The gastric proton pump, a heterodimeric protein encoded by the genes ATP4A and ATP4B, is highly conserved in vertebrates and can pump protons against a 160 mM gradient [20]. The acidic gastric pH facilitates the action of the aspartic endopeptidase pepsin, which evolutionarily led to an extension of dietary protein sources [21,22]. Pepsinogens are fundamental for acid–peptic digestion where the conversion from pepsinogen to pepsin (the active form) is promoted by both HCl and auto-catalysis [23,24]. In this way, gastric acidity promotes protein digestion and cell lysis, facilitating the release and absorption of nutrients [25], improving PO43− and Ca2+ uptake, and providing innate immune protection against pathogen entry into the intestine [19,22,26].

Surprisingly, despite the major advantages of a functional acid–peptic stomach, several secondary loss events of structure and function have occurred in the gnathostome lineage, most commonly in the Teleostei, but also in the Holocephali, dipnoids and monotremes [21,27–29]. Many pressures have been identified as potential drivers for stomach digestive function loss, such as alimentary habits, the high energy cost of stomach digestive processes and the replacement of the gastric function for another function (e.g. gas exchange) [8,22,27,30]. In the pufferfishes, ingesting large volumes of buffered alkaline seawater (pH 8) for inflation would neutralize stomach acidity and make acidification energetically more expensive, thus relaxing selective pressures for the retention of this trait, leading to its eventual loss. We hypothesize that the inflation observed in these other stomach inflators has had the same impact on GG function and acid–peptic digestion as observed with the agastric pufferfishes (figure 1) resulting in the secondary loss of acid–peptic digestion through convergent evolution.

To address the hypothesis that stomach inflation could constitute a specific trigger for the loss of a functional (acid–peptic digestion) stomach in marine fishes, we analysed the stomach phenotype of four distinct species: the sargassum fish, swellshark, bearded goby and pigmy leatherjacket (Brachaluteres jacksonianus). To explore stomach functionality a number of robust gastric trait markers were analysed: (i) the luminal pH, which gives a clear indication of the presence of gastric acid secretion [25,31] (in sargassum fish and swellshark only); (ii) histological evidence of GG and zymogen granules, and Atp4a localization by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and (iii) genetic evidence of gastric genes (atp4a) through mRNA or genomic expression although only pga and pgc in sargassum fish and swellshark [21,27].

2. Material and methods

(a) Animal husbandry

Adult sargassum fish were purchased through an aquarium fish supplier and maintained in aquaria at 25°C (33 ppt), under a controlled photoperiod (12L/12D h) and fed daily until 48 h prior to sampling (n = 5). Swellsharks were hatched from eggs and maintained in flow-through aquaria at 12–16°C, under a 12 L/12 D h photoperiod and feed three times weekly but were not fed 48 h prior to sampling. Swellsharks were sampled within two weeks post-hatching (n = 8). Animal collection and use was approved by WLU and SIO-UCSD animal care committees under protocols R18003 and no. S10320 in compliance with the CCAC and IACUC guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals, respectively. Formalin-fixed specimens of bearded goby (n = 15) and pygmy leatherjacket (n = 5) were sourced from the Hokkaido University Museum and Australian Museum Ichthyology collections, respectively (voucher codes in the electronic supplementary material, table S1). For gDNA extraction, pigmy leatherjacket tissues were also provided by the Australian Museum (n = 5), while frozen fin clips of bearded goby (n = 12) were obtained from a 2017 research cruise (provided by A.G. Salvanes. U. Bergen, Norway).

(b) pH measurements

In situ pH was acquired from three sargassum fish and eight swellsharks. Animals were anaesthetized with tricaine methane sulfonate (MS222) in seawater [1 : 10 000 (w : v)] and stomach pH was directly recorded with a small diameter pH probe (Hamilton Biotrode with Radiometer ION85 pH metre for sargassum fish; HACH pHC4000–8 with Denver Instrument UB-10 for swellshark). One swellshark inflated during the pH measurement, so those data were excluded.

(c) Sampling

Sargassum fish (n = 5) and swellsharks (n = 3) were euthanized with an overdose of neutralized MS222 [1 : 5000], followed by spinal transection. The entire gastrointestinal tract was excised and flushed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and further immersion fixed for 24 h. Tissue was then stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C. In separate animals, small pieces of stomach tissue were excised and preserved in RNAlater™ and stored at −20°C.

(d) Histology/immunohistochemistry

Sagittal sections of the cardiac stomach, cardiac–pyloric junction and the pyloric stomach were prepared for histological and immunohistochemistry analyses following paraffin embedding [32]. The gastric proton pump Atp4a was detected using the rabbit polyclonal αR1 antibody [32], a pan-specific P-type ATPase antibody where an apical localization is indicative of Atp4a staining [33]. The mouse monoclonal Na+ : K+ : 2Cl− co-transporter (NKCC) antibody (T4) or Na+/K+-ATPase (NKA) antibody (α5) were used as basolateral markers [34]. The negative controls were normal rabbit serum and the mouse J3 clone, respectively. Secondary antibodies included goat anti-rabbit Alexa488 and anti-mouse Alexa555. Sections were counterstained with the nuclear stain DAPI. Additional sections were stained with either haematoxylin and eosin, or Alcian blue (pH 2.5), and periodic acid Schiff (PAS). Eosinophilic zymogen granules were imaged using fluorescence detection.

(e) Gene expression and phylogenetics

Sargassum fish and swellshark: RNA was isolated using the Bio-Rad Aurum Total RNA Mini Kit, with on-column DNase I treatment [33]. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to isolate atp4a, pga and pgc from sargassum fish and swellshark gastric tissues using the Phusion(™) Flash hot start high fidelity polymerase mix (Life Technologies; details in electronic supplementary material, table S2).

Bearded goby and pygmy leatherjacket: since specimen preservation methods precluded the extraction of RNA, gDNA was isolated from fin clips using the Wizard®SV Genomic DNA Purification System (Promega). Genes encoding for the gastric proton pump were amplified by PCR with degenerate primer designed for atp4a and atp4b using MegaFi 2xMasterMix (Applied Biological Materials, electronic supplementary material, table S2) [35]. A β-actin PCR [36] was used to confirm gDNA quality and Astyanax mexicanus (a gastric species) gDNA was used as a positive control for the presence of the atp4a and atp4b genes. Bands in the predicted size range were retrieved, cloned and sequenced. Sequences were analysed through a translated nucleotide blast (tblastx, NCBI) and confirmed as the target genes. The sequence data for phylogenetic analyses were obtained from GenBank and Ensembl (electronic supplementary material, table S3).

The evolutionary histories of pgc, pga and atp4a (sargassum fish and swellshark) were inferred using the maximum-likelihood method [37] in MEGA-X [38]. The bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 1000 replicates [39] was taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analysed. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated from the dataset.

3. Results

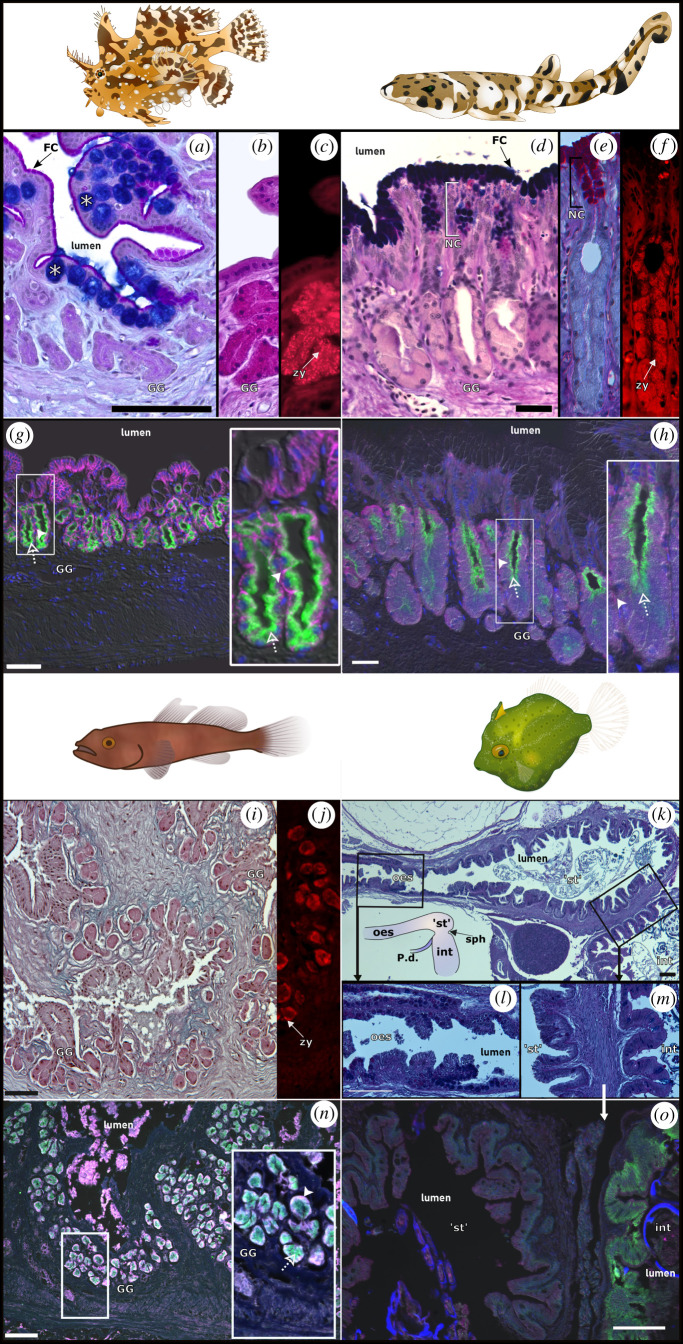

The first line of evidence for the retention of gastric acid secretion was obtained through in situ measurements of acidic luminal pH values in the sargassum fish and swellshark, which were 3.52 ± 0.43 (n = 3) and pH 2.76 ± 0.23 (n = 8), respectively. These low pH values indicate the active net secretion of acid into the stomach lumen by the gastric proton pump. Histological and immunohistochemical analyses revealed tubular type (sargassum fish and swellshark) and acinar type (bearded goby) GG in the mucosa with mucus neck cells (NC) and zymogenic oxynticopeptic cells (figure 2a–f,i). The presence of basic mucin PAS staining in foveolar mucus secreting cells lining the surface of the stomach provides a protective layer against secreted gastric juices. The observation of zymogen granules (pepsinogen detected by eosin fluorescence) provides evidence for glandular activity. In the sargassum fish's stomach, the mucosa also contained Alcian blue-staining goblet cells (figure 2a) which are not typically found in the epithelium lining the stomach [27]. The immunohistochemical staining demonstrated the presence of the gastric proton pump, detected apically in oxynticopeptic cells. Additionally, the NKCC and NKA were detected basolaterally in these cells (figure 2g,h,n; electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Conversely, no GG, eosinophilic zymogen granules, nor the associated immunodetection of the proton pump, were identified in the pygmy leatherjacket (figure 2k–m,o). However, the αR1 antibody was capable of detecting NKA in the intestine indicating that antibody cross-reactivity was not the issue. Negative control staining is shown in the electronic supplementary material, figure S1.

Stomach histology of sargassum fish (a–c), swellshark (d–f), bearded goby (i,j) and leatherjacket (k–m). Alcian blue-PAS staining (a,d,i,k,l,m) identifies mucous cells [NC and foveolar cells (FC)] with basic mucins staining purple/blue which are absent in leatherjacket (m). In the sargassum fish, Alcian blue-staining goblet cells (*) are also present in the surface epithelium. PAS staining (b,e) only. The presence of acinar type GG is noted on the bearded goby (i), while tubular type GG are present in the sargassum fish and swellshark (e,g,h). Zymogen (pepsinogen, zy) identified as eosinophilic granules in GG oxynticopeptic cells (c,f,j). The foregut of the leatherjacket (k) lacking GG is shown for precise localization of the ‘stomach’ (st), delimited by the oesophagus (oes) and the pyloric sphincter (sph) before the intestine (int) where there is a connection to the pancreatic duct (P.d.). Immunostained sections (g,h,n) showing apically localized proton pump (green, dashed arrows) and NKCC in a basolateral position (magenta, full arrowheads) with DAPI nuclear counterstaining and DIC image overlay (g,h,n,o). The leatherjacket ‘stomach’ (o) lacks proton pump immunoreactivity. Scale bars, 50 µm. Insets with an additional 3× (g) and 2× (h, n). n = 5.

The gene expression studies complemented the identification of the gastric gene repertoire in both the sargassum fish and swellshark and provided further evidence for the presence of the gastric proton pump components and pepsinogens. Partial coding sequences for atp4a, pga and pgc were deposited in GenBank (accession numbers: KY622002; KY622001; KY622003; MT329736; MT329735; MT329734). Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees were retrieved to explore the evolutionary histories of the sargassum fish and swellshark's Atp4a, Pga and Pgc in relation to related genes in other vertebrate groups (electronic supplementary material, figures S2 and S3). The phylogenetic analyses inferred a grouping with homologues of the teleost group for the sargassum fish and with homologues of chondrichthyans for the swellshark.

The bearded goby atp4a and atp4b genes were identified, and partial gDNA sequences recovered (accession OK649428 and OK649429, respectively). Sequences showed 96% identity to Morone saxatilis Atp4a, and 92% of identity to Gadus morhua Atp4b. No atp4a or atp4b genes were identified in the pygmy leatherjacket.

4. Discussion

Convergent evolution, the emergence of similar traits in different taxa in response to similar biotic and abiotic challenges, is a widespread phenomenon in biology [40,41]. Genes controlling functions that interact in a direct way with the environment will most likely be involved in convergent evolution [40]. This study explores two traits that have arisen in multiple lineages through convergent evolution: the loss of the gastric gene repertoire and body inflation. Furthermore, it was our aim to investigate the possible link between these two traits, i.e. if body inflation was correlated with the absence of a functional stomach—as it is the case of the two tetraodontiform sister families, Diodontidae and Tetraodontidae.

Several hypotheses for drivers of stomach modification and loss have been suggested including alternative functions such as defence by inflation [27]. Earlier studies indicate that the stomach loss phenotype is correlated with the absence of the gastric proton pump (ATP4A and ATP4B) and pepsinogen genes [21,29]. The presence of these genes is therefore a good predictor of a functional stomach, complementing histological techniques that allow the identification of GG and protective mucins. In this study, we have employed a set of molecular tools in combination with histological analyses to investigate the presence of a functional stomach in four representative inflator fish lineages. In addition, the use of museum specimens (in the case of the bearded goby and pygmy leatherjacket) allowed us to obtain valuable datasets (histology, IHC and gene presence) while reducing the use of wild-caught animals. We found that the gastric phenotype was retained in most of the study species, with exception of the pygmy leatherjacket, a member of the Tetraodontiformes.

The inflation trait, which is more often associated with the puffer and porcupine fishes, presents an effective solution in response to predatory and territory defence pressures [5]. Several morphological adaptations including new mechanisms of buccal expansion and the high elasticity of stomach and skin have enabled inflation in these Tetraodontiform families [7,42]. The sargassum fish's ability swallow prey considerably larger than themselves by making use of extendable buccal components and stomach has been documented [9,10]. The a priori presence of buccal and morphological modifications that allow for the rapid uptake of large amounts of water (or food) might have aided the emergence and fixation of the inflation trait.

The convergent nature of the inflation trait had been noted by Wainwright and Turingan [42], particularly related to the Brachaluteres genus of the Monochanthidae that, together with the triggerfishes (Balistidae), belongs to a sister clade to the Diodontidae and Tetraodontidae [43]. However, no inflation has been reported in the Balistidae [42] and a functional stomach is present [17]. This makes the agastric phenotype found in the Brachaluteres, a case of secondary loss of gastric function, in a full convergence to the agastric-inflator phenotype found in the Diodontidae and Tetraodontidae.

The retention of the gastric phenotype, coupled with inflation capacity, could have arisen from differences in selective pressures imposed by habitat and diet [44–48]. However, since loss would have occurred in the ancestor, linking these factors, which are unknown, is problematic in the analysis of extant groups. Interestingly, one of the swellsharks in our study inflated during gastric pH measurement which increased from pH 3.4 to 8.7, providing evidence that stomach swelling can indeed affect acidic digestion. Thus, another plausible explanation may be that inflation is not being used as promptly and/or frequently in the three gastric-inflator species analysed, for example, it may not be used during the post-prandial period. This behaviour would result in less of a negative impact on digestive function and thus as a driver for loss. This is also correlated with the observation that other morphological modification (e.g. to skeletal–muscular and integument) are not as prevalent, and inflation is not to the same extent outside of the puffer and porcupine fishes [42]. In summary, this study has succeeded in demonstrating the prevalence of the gastric acid–peptic digestion in combination with body inflation in distinct fish lineages.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Amanda Hay (Australian Museum, Australia) for providing the pygmy leatherjacket voucher specimens, and Dr Anne Gro Salvanes (U. Bergen, Norway) for providing bearded goby fin clips. The mouse monoclonal antibodies were obtained from the DSHB, created by the NICHD of the NIH (U. Iowa, Depart. Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242).

Data accessibility

All data (accession number of sequences used in the analyses) can be consulted in the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

P.F.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, writing—original draft and writing—review & editing; G.K.: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology and writing—review and editing; S.H.: formal analysis, investigation, methodology and writing; J.L.R.: investigation and writing—review and editing; F.T.: methodology and writing—review and editing; L.F.C.C.: investigation and writing—review and editing; M.T.: funding acquisition, investigation, methodology and writing—review and editing; J.M.W.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Funding

NSERC Discovery and CFI grants to J.M.W. NSF grant to M.T. (NSF-IOS#1754994), Ontario Graduate Scholarship to P.G.F. and Graduate Research Fellowship to G.T.K.

References

Articles from Biology Letters are provided here courtesy of The Royal Society

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2021.0583

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8807057

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/121941395

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1098/rsbl.2021.0583

Article citations

Pseudogenization of NK3 homeobox 2 (Nkx3.2) in monotremes provides insight into unique gastric anatomy and physiology.

Open Biol, 14(7):240071, 03 Jul 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38955222 | PMCID: PMC11285752

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

Nucleotide Sequences (Showing 6 of 6)

- (1 citation) ENA - KY622001

- (1 citation) ENA - KY622002

- (1 citation) ENA - KY622003

- (1 citation) ENA - MT329734

- (1 citation) ENA - MT329735

- (1 citation) ENA - MT329736

Show less

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

The gastric proton pump in gobiid and mudskipper fishes. Evidence of stomach loss?

Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol, 274:111300, 27 Aug 2022

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 36031062

EVOLUTION OF PUFFERFISH INFLATION BEHAVIOR.

Evolution, 51(2):506-518, 01 Apr 1997

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 28565363

Trophic structure and community stability in an overfished ecosystem.

Science, 329(5989):333-336, 01 Jul 2010

Cited by: 25 articles | PMID: 20647468

Gastric acid and digestive physiology.

Surg Clin North Am, 91(5):977-982, 01 Oct 2011

Cited by: 14 articles | PMID: 21889024

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Canada Foundation for Innovation (1)

Grant ID: 32713 Grant to JMW

Canadian Network for Research and Innovation in Machining Technology, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (1)

Grant ID: RGPIN-2014-04289 grant to JMW

Graduate Research Fellowship (1)

Grant ID: to GK

NSF (1)

Grant ID: NSF IOS #1754994 to MT

Ontario graduate Scholarship (1)

Grant ID: to PGF

1

,

2

,

3

1

,

2

,

3