Abstract

Free full text

Keys to Driving Implementation of the New Kidney Care Models

Abstract

Contemporary nephrology practice is heavily weighted toward in-center hemodialysis, reflective of decisions on infrastructure and personnel in response to decades of policy. The Advancing American Kidney Health initiative seeks to transform care for patients and providers. Under the initiative’s framework, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation has launched two new care models that align patient choice with provider incentives. The mandatory ESRD Treatment Choices model requires participation by all nephrology practices in designated Hospital Referral Regions, randomly selecting 30% of all Hospital Referral Regions across the United States for participation, with the remaining Hospital Referral Regions serving as controls. The voluntary Kidney Care Choices model offers alternative payment programs open to nephrology practices throughout the country. To help organize implementation of the models, we developed Driver Diagrams that serve as blueprints to identify structures, processes, and norms and generate intervention concepts. We focused on two goals that are directly applicable to nephrology practices and central to the incentive structure of the ESRD Treatment Choices and Kidney Care Choices: (1) increasing utilization of home dialysis, and (2) increasing the number of kidney transplants. Several recurring themes became apparent with implementation. Multiple stakeholders from assorted backgrounds are needed. Communication with primary care providers will facilitate timely referrals, education, and comanagement. Nephrology providers (nephrologists, nursing, dialysis organizations, others) must lead implementation. Patient engagement at nearly every step will help achieve the aims of the models. Advocacy with federal and state regulatory agencies will be crucial to expanding home dialysis and transplantation access. Although the models hold promise to improve choices and outcomes for many patients, we must be vigilant that they not do reinforce existing disparities in health care or widen known racial, socioeconomic, or geographic gaps. The Advancing American Kidney Health initiative has the potential to usher in a new era of value-based care for nephrology.

Introduction

With the announcement of the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) initiative in July 2019 (1), the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) has focused attention on kidney care to operationalize the initiative’s three broad goals: (1) reduce ESKD, with 25% fewer patients with incident ESKD by 2030; (2) improve access to person-centered treatments for kidney failure (home dialysis and kidney transplantation), with the goal that 80% of new patients with kidney failure in 2025 will receive either dialysis at home or a transplant; and (3) increase access to kidney transplantation by doubling the number of organs available for transplantation by 2030. The two resulting payment models, the ESRD Treatment Choices (ETC) (2) and the Kidney Care Choices (KCC) (3), both align incentives with patient-centered goals using differing approaches. In this article, we discuss these models in the context of previous policy efforts, and the changes that assign significant financial responsibility to nephrologists. We have developed Driver Diagrams to guide nephrology providers along the many steps for implementation and identified the varied stakeholders and their specific contributions. Finally, we discuss the unintended potential for widening existing disparities in kidney care.

Background

Since the inception of the ESRD program, federal legislation and policies (Table 1) have focused on the refinement of care for patients with kidney failure (4–20). Although pioneering the first disease-specific capitated system and pay for performance in Medicare, most policies addressing payment have primarily affected dialysis organizations rather than nephrology practices. Policies addressing payments directly to nephrologists have had mixed results for home dialysis rates (21,22), and low utilization for education of patients with stage 4 CKD (23). The Comprehensive ESRD Care model tested a voluntary program in which both nephrologists and dialysis providers for the first time were jointly responsible for the total cost of care for patients receiving dialysis; yet the majority of the ESRD Seamless Care Organizations (ESCOs) drew upon the administrative experience and infrastructure of large dialysis organizations for operationalization (15). Few programs, furthermore, incorporated patient preferences or incentivized transplantation.

Table 1.

Key policy/legislative acts for kidney care before the Advancing American Kidney Health initiative

| Year | Event | Result(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1967 | Gottschalk Committee Report (4) | Established the background for federal legislation to cover dialysis, estimated 10,000 patients annually |

| 1972 | Public Law 92–603 (5) | Authorization of Medicare payments for dialysis and transplantation with the establishment of the ESRD program |

| 1978 | Public Law 95–292 (6) | Established prospective composite rate of payment for dialysis |

| 1984 | Public Law 98–507 (7) | Established the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network through the National Organ Transplantation Act |

| 1986 | Public Law 99–509 (8) | Medicare coverage of immunosuppressive medications for 12 months, eventually extended to 36 months |

| 1998 | CMS - ESRD Managed Care Demonstration Project (9) | Enhanced coverage capitated payments (for total cost of care) with quality metrics for patients on dialysis in parts of Southern California, Tennessee, and Florida with quality metrics |

| 2003 | Public Law 108–173 (10) | Medicare Modernization Act; 1.5% increase in composite dialysis rate; add-on charges for dialysis-related drugs/biologics; required study of expanding the dialysis bundle |

| 2007 | CMS conditions of participation (19) | Quality measures for participation of transplant centers in Medicare |

| 2008 | Public Law 110–275 (11) | Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act; bundled dialysis payments (year 2011) linked to Quality Incentive Program (year 2012) with final rule adding payment for home training |

| 2012 | Public Law 112–240 (12) | American Taxpayer Relief Act: reduced the payment for bundled dialysis-related drugs; delayed inclusion of oral-only drugs in the bundle until 2016 |

| 2015 | CMS Dialysis Facilities Compare 5 Star Ratingsa (13) | Quality ratings added to dialysis facilities compare website to inform patient choice with star ratings for quality (1 star, low, to 5 stars, high) |

| 2015 | CMS In-Center Hemodialysis Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Survey (20) | Patient assessment of dialysis clinics, dialysis staff, and providers; introduced as a quality measure |

| 2015 | CMS Comprehensive ESRD Care Model (15) | Formation of ESRD seamless care organizations to cover total cost of care for patients receiving dialysis |

| 2018 | CMS Conditions of Participation, revised (16) | Threshold for value for categorizing underperforming transplant centers raised |

| 2019 | SRTR 5 Star Rating (17) | HRSA/SRTR website with 5-star rating of transplant centers |

CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; SRTR, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients; HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration.

The contemporary practice landscape reflects decisions on infrastructure/personnel on the basis of these policies. Under a predominantly fee-for-service model for patients with nondialysis CKD, nephrology practices had no mandates to coordinate patient transitions to KRT with other medical providers, dialysis organizations, transplant centers, or health care systems. Dialysis organizations have built on 50 years of experience to adapt and remain profitable, even after the enactment of bundled payments (24). In-center hemodialysis endures as the default and dominant therapy for individuals with kidney failure. An alarmingly high percentage of patients still start hemodialysis without nephrology precare and with a catheter (25,26).

The New Payment Models

The mandatory ETC model, which began on January 1, 2021, requires participation by all nephrology practices within designated Hospital Referral Regions (HRRs) (Table 2). Designed as the largest national health policy experiment for kidney disease, CMMI randomly selected 30% of all HRRs for participation. The remaining HRRs serve as controls to assess the effect of the plan. The ETC focuses exclusively on traditional fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries receiving dialysis, and excludes individuals with advanced age (>75 years), poor functional status (long-term resident of skilled nursing facility), and comorbidities (e.g., dementia and active cancer) from the calculation of home dialysis and transplant rates. It uses two financial incentives to increase the rate of home dialysis and transplantation for patients on prevalent and incident dialysis. First, the model increases payments for all home dialysis–related claims for managing clinicians and facilities for its first 3 years. The home dialysis adjustment is 3% in 2021, 2% in 2022, and 1% in 2023, and sunsets in 2024. Second, the model applies a Performance Payment Adjustment to all monthly capitated payments for nephrologists, and to all composite dialysis payments for dialysis clinics starting in the middle of performance year 2 on the basis of the Modality Performance Score (MPS). The MPS is composed of differentially weighted home dialysis and kidney transplant rates that are separately assessed for nephrologists and dialysis clinics. The composite MPS score for each group (nephrologist or dialysis clinic) is generated either by comparing current performance rates for home dialysis and transplant to their past performance, or by comparing current performance rates to those of nephrologists and dialysis clinics in non-ETC HRRs. Upward and downward adjustments on the basis of the composite MPS for all dialysis claims—home and in-center—were not in effect for 2021, but will begin at 3%–4% in July 2022, and rise to 10% through the final year of the model ending June 30, 2027.

Table 2.

Overview of ESRD Treatment Choices and Kidney Care Choices models

| Model | Participants | Selected Patients | Goals | Metrics, Payments, and Adjustments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESRD Treatment Choices | Nephrology practices and dialysis clinics in selected hospital referral region | Medicare Fee-For-Service patients; receiving kidney replacement therapy with no minimum number |

|

|

| Kidney Care Choices | ||||

Kidney Care First option Kidney Care First option | Nephrologists/nephrology practices only | Medicare Fee-For-Service patients:

| Improve CKD stage 4–5 care

|

|

CKCC options CKCC options

| Nephrologist/nephrology practices, transplant providers (required); dialysis facilities, and other providers (optional) | Medicare Fee-For-Service patients:

| Improve CKD stage 4–5 care

|

|

CKCC, Comprehensive Kidney Care Contracting.

The KCC models, onset January 2022, are voluntary, alternative payment models open to nephrology practices throughout the country (Table 2). Like the ETC, these models apply to traditional fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries receiving maintenance dialysis; however, they also attribute Medicare beneficiaries with CKD stages 4 or 5. This inclusion of patients with late-stage CKD is a logical next step in the evolution of kidney care to focus on prevention and preparation. It has the potential to be greatly impactful, incentivizing strategies in this population to delay progression to kidney failure and, if needed, a healthy transition to KRT. The KCC models exclude patients enrolled in commercial or Medicare Advantage plans, or those already attributed to Accountable Care Organizations. Participants in a KCC can choose either a Kidney Care First (KCF) or Comprehensive Kidney Care Contracting (CKCC) option. Akin to the recently deployed Primary Care First model (27), the KCF is organized around an individual nephrology practice, or an aggregated group of practices if necessary to meet the required number of patients. CKCCs have their origin in the now-lapsed ESCOs (15). Each type of CKCC is administratively organized as a Kidney Contracting Entity (KCE). The KCE requires both a nephrologist and transplant provider as a foundation, and will likely include a dialysis organization.

Payments and financial incentives for the KCC vary in complexity compared with the ETC. All clinicians or organizations participating in KCC will receive an Adjusted Monthly Capitated Payment for traditional dialysis care, and a new Quarterly Capitation Payment for care for patients with CKD stages 4 or 5. These payments will be adjusted on the basis of the Performance-Based Adjustment, reflecting performance on metrics either relative to national benchmarks or to previous performance. The Performance-Based Adjustment can result in an upward or downward adjustment of up to 20%–30% to the Adjusted Monthly Capitated Payment and the Quarterly Capitation Payment. A Kidney Transplant Bonus of up to $15,000 will also be paid to a KCF or KCE for each successful kidney transplant that continues to function, including preemptive transplants. The bonus consists of $2500 after the first year of allograft function, $5000 after the second year, and $7500 after the third year. The KCEs can opt for varying degrees of shared savings or losses within the total cost of care framework for patients having Medicare parts A and B; the shared savings/loss associated with the KCE options range from 0% for the first year of the one-sided risk Graduated option to 50% for the Professional option and 100% for the Global option, adjusted for performance on quality measures. Finally, all of the KCC model options, with the exception of the first year of the KCE Graduated option, are considered advanced alternative payment models, with participating clinicians qualifying for maximum bonuses under the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS’s) Quality Payment Program.

CMMI seeks to transform kidney care. Both programs directly incentivize home dialysis and kidney transplantation. They also coax coordinated nondialysis CKD care to educate patients on optimal choices for KRT, and conservative management. Notably, some practices will be subject to the mandatory ETC and may choose to participate in the KCC.

The new approaches, albeit intuitive in the evolution of care, may catch providers underprepared. The ETC, and to a greater extent the KCC, assigns financial accountability primarily to nephrologists, who have traditionally lacked experience with performance-based capitated payments or with population health management. Furthermore, the plans lack direct support to mitigate the effect of the social determinants (e.g., economic stability) on health outcomes. In contrast, dialysis providers and health care systems have years of experience with management of large populations in a shared saving/loss framework (28–30) and can draw upon a preexisting infrastructure of personnel and care processes.

Operationalizing the Models

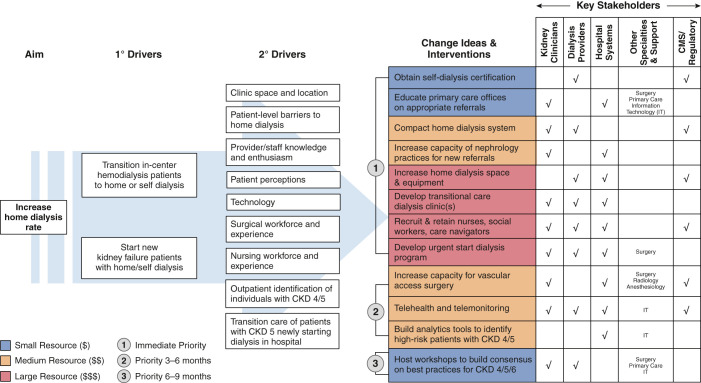

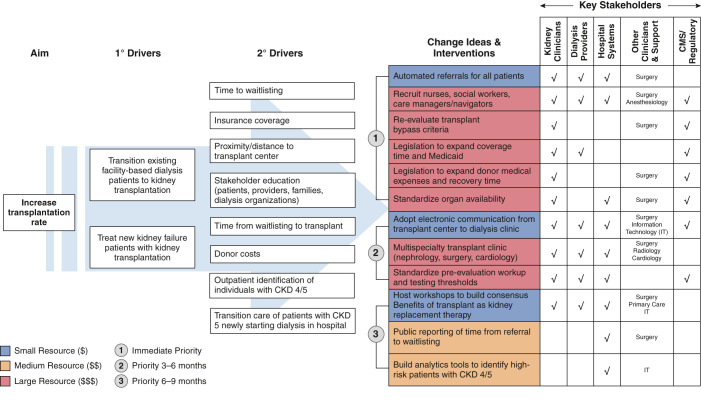

We developed a Driver Diagram (31–33) to help organize operationalization of the new models. Driver Diagrams can serve as a detailed outline to identify stakeholders (new and old), structures, processes, and norms and generate ideas and interventions that facilitate coordination across transitions of care. Two authors (A.V.K., J.Z.) drafted the initial diagram in response to the CMMI’s request for participation in the KCC, with direct input from the University of North Carolina health care system leadership, large dialysis organization leadership, transplant nephrology/surgery, and community nephrologists about the primary or secondary drivers, specific intervention ideas, stakeholders, and expected resource allocation and prioritization. The draft diagrams were circulated among the remaining authors of the manuscript for feedback and then revised iteratively.

For model implementation, we focused on two goals that are directly applicable (and attributable) to nephrology practices throughout the country: increasing utilization of home dialysis (Figure 1) and increasing the number of kidney transplants (Figure 2). Both goals are central to the ETC and KCC. We developed a separate Driver Diagram for each of these two primary goals. We also modified each diagram to prioritize the timing of specific changes (Priority 1, 2, or 3) and to weight the potential resource allocation (blue small, orange medium, and red large) by the key stakeholders.

The primary drivers identified to achieve these aims are transitioning prevalent patients away from in-center hemodialysis and treating patients with incident kidney failure with home dialysis, self-dialysis, or transplantation. In turn, many more secondary drivers help to accomplish the goals of the primary drivers for each specific aim. Some of the overlapping concepts from the secondary drivers for both aims include: (1) setting concrete goals for the numbers of days for patients to transition to home dialysis and kidney transplantation; (2) educating all patients located in outpatient and inpatient settings about all kidney disease treatment options, including home therapies, kidney transplantation, and conservative nondialysis care; (3) supporting all patients in navigating the transition to home dialysis therapies, or the multiple steps to kidney transplantation in a manner consistent with the patients’ preferences, while recognizing the challenges from their socioeconomic status and other factors interfering with their ability to access care; (4) educating providers—nephrologists, referring primary care physicians (PCPs), other specialists, surgeons—on current strategies to delay progression of CKD and the potential advantages of alternatives to in-center dialysis; and (5) increasing timely referral of patients at risk for KRT to nephrology for planning options.

We identified several specific interventions to achieve the two aims. Yet, we acknowledge the potential for overlap of the articulated interventions and the possibility of an incomplete enumeration. Furthermore, timing of the interventions and resource allocation may differ by health care system or region. Several recurring themes are apparent.

First, multiple stakeholders from assorted backgrounds must participate for implementation. Nephrology providers (nephrologists and dialysis organizations) must engage hospital systems, surgeons, and other specialists to ensure adequate resources, including infrastructure capacity for dialysis access placement, and waitlisting with eventual kidney transplantation. For example, the creation of arteriovenous fistulas or insertion of peritoneal dialysis catheters requires a “small village,” starting with intake personnel accepting referrals from nephrology, and then a team that includes administrative support, surgeon, operating room personnel, and time and physical space for the procedure. Postoperatively, a different set of personnel and resources are needed to manage complications and to intervene in a timely manner for a slowly maturing access. A kidney transplant evaluation requires an even larger team, including skilled pretransplant coordinators to manage the evaluation-to-waitlisting process, which may require consultation with cardiology, gastroenterology, endocrinology, urology, and infectious disease, and a tissue typing lab, care navigators, pharmacists, and social workers. An adequately resourced pretransplant team is necessary to not only coordinate clinical activity that results from the increased referrals, but also to continue to maintain an expanding waitlist of patients as “transplant ready” for unpredictable organ offers.

Second, high-quality communication with PCPs is necessary for referrals, education, and comanagement. Nephrology providers must engage with PCPs early to identify patients at high risk of CKD progression. Early identification would allow timely intervention with new agents to slow progression and would present a meaningful opportunity to educate patients about home dialysis and kidney transplantation. PCPs have unique patient relationships that have been nurtured over the years and could help initiate/facilitate discussions about KRT or conservative care in partnership with nephrologists when appropriate. PCPs need a basic understanding of the different modalities of KRT and the steps for evaluation. Currently, PCPs lack the training (34) to become the key advisors on KRT decisions, despite their potential greater insights into individual patients’ goals and broader health and social factors than nephrologists. Electronic health records (EHR) may provide the nexus for education and dialogue between providers and patients. In the near term, artificial intelligence technology in the EHR holds promise (35,36) to identify then alert clinicians of patients at high risk of developing advanced CKD and kidney failure. Information technology services can help to build the infrastructure into the EHR to connect patients, PCPs, and nephrologists.

Third, nephrology providers must collectively lead implementation, by dedicating time and resources to promote greater home dialysis and transplantation utilization. Increased access to transplantation will require early patient education of their options, advocating for living donors, and referrals to transplant centers that provide increased access to transplant waitlists and a high probability of transplantation (37–40). Nephrology providers should ensure adequate capacity (personnel and infrastructure) for the increase in utilization of home dialysis and referrals from primary care, and developing transition units and urgent start home dialysis programs, or self-dialysis programs (41). Transition units, sometimes called Transitional Care Units (TCUs), share many characteristics of home training programs and allow new patients a supportive low-risk environment to sample home therapies (usually home hemodialysis) (42). Importantly, TCUs, urgent start programs, and self-dialysis care generally do not need additional certifications at present, but existing staff are responsible for managing these resource-intensive efforts. Furthermore, nephrology providers must educate health care systems and PCPs about their critical roles in improving the health of patients with advanced CKD. There are no direct incentives for either of these stakeholder groups in traditional fee-for-service models. Yet, nephrology can invoke both moral and financial arguments to persuade the stakeholders. Offering patients their preferred therapies and improving outcomes can result in higher patient satisfaction and reduced hospitalizations, readmissions, and mortality. With the expected growth in value-based care, nephrologists must guide health care systems in partnerships that assume single- and double-sided risk for high utilization groups, such as patients with advanced CKD. The results from the ESCOs suggested potential for such shared savings for partnerships between nephrologists and large organizations, although predominantly in urban areas (28,43).

Fourth, engaging in advocacy with federal and state regulatory agencies will be crucial to expanding home dialysis and transplantation. The shortage of dialysis nurses (44,45) likely will worsen with an increased shift to home dialysis, which is more nurse- and less patient care technician–intensive than in-center hemodialysis. Currently, home dialysis nurses require a Registered Nurse certification, 12 months of work experience as a dialysis nurse, and an additional 3 months of experience in the home dialysis modality before they are allowed to train patients independently. Practically, these requirements limit the pool of qualified personnel to existing dialysis nurses, magnifying the paucity of new nursing graduates choosing dialysis as an area of interest (46). State regulatory agencies could consider adjusting the requirements of certification or duration of work experience to increase the nursing pool for home therapies. Federal agencies could consider student loan forgiveness to incentivize new nursing graduates to choose nephrology or dialysis. Furthermore, the lack of explicit nationwide standards for training may incentivize some dialysis service organizations that lack a robust home dialysis staff to deliver a minimum level of personnel-intensive training of surrogates. Hurrying patients out of dialysis clinics to home therapies could increase morbidity and would make the field less attractive to new nursing graduates.

As centers increase capacity, legislative changes and regulatory scrutiny are also needed. Transplant centers avoided using suboptimal deceased donor organs when the CMS conditions of participation required excellent early post-transplant outcomes (47); CMS then withdrew these outcome metrics. The CMS and the Health Resources and Services Administration are launching the ETC Learning Collaborative to identify best practices that: (1) increase annual transplants; (2) decrease discards; and (3) increase procurement of deceased kidneys with a kidney donor profile index of 60%–80%. Although record numbers of deceased donor transplants occurred in 2020, 5000 kidneys were discarded (48–50). In 2021, the discard rate will likely exceed the 2020 rate (38,51–53). Although recent reforms in accountability for organ procurement organizations have increased procurement, these changes need parallel efforts to improve utilization. This requires improved accountability from transplant centers for both organ offer decisions and selective waitlisting of patients, and new metrics development (38,54). Efforts to increase transplantation without complementary focus on the organ supply may result in a zero-sum competition for a fixed number of kidneys.

We can draw some hope from recent legislative successes, including the “Immuno Bill” (H.R.5534) expanding Medicare coverage for immunosuppressive medications (55). Medicaid expansion has positively affected kidney transplantation access (56). Changes in the allocation criteria in 2014 have improved transplantation disparities but may have adversely affected waitlisting rates (40,57).

Most importantly, patient engagement will be crucial to achieving the aims of the models. Inviting patient advocates at the start of a program could help in both planning and implementing while also ensuring the focus remains on issues most relevant to patients. In established programs, ongoing patient feedback is necessary for continuous improvement. Patient advocates can provide insights into community norms and attitudes to inform strategies on education about kidney health and treatment options. Peers sharing stories of their journey often provide priceless support, reassurance, and valuable insights to new patients navigating home dialysis and kidney transplantation (58).

Potential Unintended Consequences

Successful implementation of the models within the AAKH initiative requires a coordinated effort from multiple, engaged stakeholders and, ideally, adequate health care and community resources to address social determinants of health challenges. Dialysis clinics with home therapy capacity do not exist in many communities (59). Centers for transplantation may be far from dialysis clinics (44) and may not have the capacity to handle a surge of referrals. The availability of surgeons and the supporting infrastructure vary greatly (44,60). Homelessness, food insecurity, and a lack of insurance can create significant hurdles for choices for KRT (61,62). In communities with low resources, existing disparities in access to home dialysis and transplantation may be exacerbated, especially if penalties force providers to drop markets. Indeed, data from early adopters of value-based care in other fields demonstrate that health systems with patients who are socially disadvantaged are disproportionately penalized (63,64).

The initial AAKH initiative proposal did not include specific measures that address health care equity or disparities, despite its innovative approach and patient-centric goals. Given that we are in the first phase of adoption, the models present an ideal opportunity to propose strategies that may mitigate widening disparities. A recent paper (65) details potential opportunities to address health disparities related to home dialysis and transplantation using incentives from the ETC and KCC: (1) participants could partner with local governments to prioritize subsidized housing for patients with kidney failure and housing instability; (2) participants could adapt TCUs to include training for self-care dialysis; and once housing is stable, patients could transition to home dialysis; and (3) participants could make investments in population health management for patients with advanced kidney disease to coordinate education and referrals for transplant and home therapies (e.g., development of EHR-based registries, care coordination for patients transitioning from advanced CKD to kidney failure and KRT). Furthermore, precise data on social determinants of health are not currently available, yet are sorely needed for accurate adjustment for communities serving disadvantaged populations.

President Biden’s Executive Order 13985 (66) seeks to improve data collection for measurement and analysis of disparities across programs and policies. It also includes a new approach to advance equity within the ESRD Quality Incentive Program framework. The novel Health Equity Incentive will promote home dialysis among patients who are dual eligible through financial incentives with the ETC (67), in recognition of the need for prospective investments to narrow gaps in care delivery among vulnerable populations.

Future Directions

The ETC and KCC models reflect a growing vision of value-based approaches to kidney care that now align patient-preferred therapies with payment reforms. Private insurers, recognizing the utility of managing patients with CKD stage 4 or 5, are emulating aspects of the KCC with new plans (68–70), while partnering with organizations or new kidney care delivery companies (71–76) using a shared saving or loss framework. Ultimately, we hope the recent attention directed toward kidney care resulting from the AAKH initiative leads to tangible and equitable improvements in the health of patients with kidney disease nationwide.

Disclosures

A.V. Kshirsagar is a voting member of the Carolina Dialysis Board; reports consultancy to Target Real World Evidence in 2021, and with Alkahest; reports receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Nursing Research); and reports serving as a scientific advisor or member of American Journal of Kidney Disease and Kidney Medicine. D.E. Weiner reports being a Medical Director of Clinical Research for Dialysis Clinic, Inc. (DCI); reports having consultancy agreements with Akebia (2020, 2021), Cara Therapeutics (2020), Janssen Biopharmaceuticals for participation in Medical Advisory Boards (2019), and Tricida (2019); reports receiving honoraria from Akebia (2020, 2021) paid to DCI; reports receiving research funding paid to their institution via DCI (local site principal investigator [PI] for clinical trials contracted through DCI sponsored by Ardelyx [ongoing] and Cara Therapeutics [completed]) and for trials sponsored by AstraZeneca (site PI, capitated on the basis of recruitment, completed 2020), CSL Behring (site PI, ongoing), Goldfinch Bio (site PI, capitated on the basis of recruitment, ongoing), and Janssen Biopharmaceuticals (site PI, capitated on the basis of recruitment, completed 2019); reports receiving honoraria from the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) for an editorial position at the American Journal of Kidney Diseases and from Elsevier for royalties from the National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases, 8th Edition and Kidney Medicine; reports being a scientific advisor or member of ASN Quality and Policy Committees and an ASN representative to KCP; reports being a scientific advisor or member of Scientific Advisory Board for National Kidney Foundation, a Co-Editor-in-Chief of National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases, 8th Edition, and Editor-in-Chief of Kidney Medicine; and having other interests/relationships as chair of the adjudications committee for the Evaluation of Effect of TRC101 on Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease in Subjects With Metabolic Acidosis Trial (George Institute), and Member of Data Monitoring Committee, “Feasibility of Hemodialysis with GARNET in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients with a Bloodstream Infection” Trial (Avania). D.L. White reports being employed by the American Society of Nephrology. F. Liu reports being involved in clinical trials involving home hemodialysis devices sponsored by CVS and Outset Medical; reports participating in advisory boards with Janssen Pharmaceutical, Medtronic Inc., and Quanta Dialysis Technologies; reports consultancy agreements with CVS Health Corporation/Accordant; reports having speaking arrangement with Janssen Pharmaceutical; reports receiving honoraria from NxStage Medical, all unrelated to the submitted work; and reports being a medical advisor for Accordant, also unrelated to the submitted work. M.L. Mendu reports having ownership interest in, and serving on the clinical advisory board of, RubiconMD. S.D. Bieber reports employment with Kootenai Health; reports being a medical director for Northwest Kidney Centers; reports being a medical director for Fresenius, receiving compensation for providing dialysis center oversight; reports serving as faculty for a home dialysis university; and reports receiving payments to lecture about home dialysis. S.Q. Lew reports receiving grants from Care First Foundation and personal fees from Reata, outside the submitted work; reports employment with Mitre; reports serving on the Board of Directors of Quality Insights and Accountable Care Organization Board of Directors of George Washington University; reports other interests/relationships with the American Society of Nephrology as a Kidney Health Initiative member, member of the coronavirus disease 2019 home dialysis subcommittee, KidneyX grant reviewer, and a Quality Committee member; and other interests/relationships as Data Safety Monitoring Board member of NIH's Kidney Precision Medical Project, National Institute on Aging grant reviewer, and member of US Food and Drug Administration Gastroenterology and Urology Devices Panel of the Food and Drug Administration's Medical Devices Advisory Committee. S. Mohan reports serving on the Angion Pharma scientific advisory board, as a member of the ASN Quality committee, as deputy editor of Kidney International Reports (International Society of Nephrology), as a member of the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients visiting committee, as vice chair of the United Network for Organ Sharing data advisory committee, and as national faculty chair for the ESRD Treatment Choices Learning Collaborative; reports having consultancy agreements with Angion Biomedica; and reports receiving research funding from Angion Biomedica and the National Institutes of Health (National Institute Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute Minority Health and Health Disparities, and National Institute Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering). T.J. O’Neil reports being the sole proprietor of HD CLEAN, a company dedicated to “making hemodialysis safer,” has a patent null pending, and is in the very early phases of submitting utility and design patents on a device to reduce the risk of both venous-line disconnection and microbial contamination of the bloodline-to-central–hemodialysis catheter-hub connection points; the effort is entirely self-funded, is not proceeding under the sponsorship or support of any other agency or business entity, and was undertaken more than a year after his retirement to without-compensation emeritus teaching staff status from the James H. Quillen Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Johnson City Tennessee; reports being a paid educational content consultant for Nephrology Curriculum at GOATCOACH, paid medical consultant for GAIA Software, and President and CEO of HD CLEAN (Dialysis); reports an ownership interest in HD CLEAN (Dialysis); and reports serving as a member of the ASN Quality Committee and an advisor of the Veterans Transplantation Association. The remaining author has nothing to disclose.

Author Contributions

A. Kshirsagar, S. Mohan, and J. Zimmerman conceptualized the study; D. Weiner was responsible for the project administration; S. Bieber, A. Kshirsagar, and D. White were responsible for the resources; S. Mohan, T. O'Neill, and D. White provided supervision; A. Kshirsagar was responsible for the visualization; A. Kshirsagar, S. Lew, F. Liu, M. Mendu, T. O'Neill, and D. Weiner wrote the original draft; and S. Bieber, A. Kshirsagar, S. Lew, F. Liu, M. Mendu, S. Mohan, T. O'Neill, D. Weiner, D. White, and J. Zimmerman reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

Articles from Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN are provided here courtesy of American Society of Nephrology

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.10880821

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://journals.lww.com/cjasn/fulltext/2022/07000/keys_to_driving_implementation_of_the_new_kidney.22.aspx

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/124631841

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.2215/cjn.10880821

Article citations

"Long-term effects of center volume on transplant outcomes in adult kidney transplant recipients".

PLoS One, 19(6):e0301425, 06 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38843258

From Home to Wearable Hemodialysis: Barriers, Progress, and Opportunities.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 19(11):1488-1495, 08 Jan 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38190138

Review

Discrepant Outcomes between National Kidney Transplant Data Registries in the United States.

J Am Soc Nephrol, 34(11):1863-1874, 03 Aug 2023

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 37535362 | PMCID: PMC10631598

Characterization of Transplant Center Decisions to Allocate Kidneys to Candidates With Lower Waiting List Priority.

JAMA Netw Open, 6(6):e2316936, 01 Jun 2023

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 37273203 | PMCID: PMC10242426

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services' Models to Improve Late-stage Chronic Kidney Disease and End-stage Renal Disease Care: Leveraging Nephrology Payment Policy to Achieve Value.

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis, 29(1):24-29, 01 Jan 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 35690399

Review

The Large Kidney Care Organizations' Experience With the New Kidney Models.

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis, 29(1):40-44, 01 Jan 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35690402

Review

Patient-Reported Experiences with Dialysis Care and Provider Visit Frequency.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 16(7):1052-1060, 12 Jul 2021

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 34597265 | PMCID: PMC8425623

Health Policy and Kidney Care in the United States: Core Curriculum 2020.

Am J Kidney Dis, 76(5):720-730, 05 Aug 2020

Cited by: 14 articles | PMID: 32771281

Review

1

,

2

1

,

2