Abstract

Free full text

Signatures of copy number alterations in human cancer

Abstract

Gains and losses of DNA are prevalent in cancer and emerge as a consequence of inter-related processes of replication stress, mitotic errors, spindle multipolarity and breakage–fusion–bridge cycles, among others, which may lead to chromosomal instability and aneuploidy1,2. These copy number alterations contribute to cancer initiation, progression and therapeutic resistance3–5. Here we present a conceptual framework to examine the patterns of copy number alterations in human cancer that is widely applicable to diverse data types, including whole-genome sequencing, whole-exome sequencing, reduced representation bisulfite sequencing, single-cell DNA sequencing and SNP6 microarray data. Deploying this framework to 9,873 cancers representing 33 human cancer types from The Cancer Genome Atlas6 revealed a set of 21 copy number signatures that explain the copy number patterns of 97% of samples. Seventeen copy number signatures were attributed to biological phenomena of whole-genome doubling, aneuploidy, loss of heterozygosity, homologous recombination deficiency, chromothripsis and haploidization. The aetiologies of four copy number signatures remain unexplained. Some cancer types harbour amplicon signatures associated with extrachromosomal DNA, disease-specific survival and proto-oncogene gains such as MDM2. In contrast to base-scale mutational signatures, no copy number signature was associated with many known exogenous cancer risk factors. Our results synthesize the global landscape of copy number alterations in human cancer by revealing a diversity of mutational processes that give rise to these alterations.

Main

Beyond alterations to single chromosomes, changes in genomic copy number can also occur through whole-genome doubling (WGD) and chromothripsis. WGD is when the entire chromosomal content of a cell is duplicated7 from a diploid to a tetraploid state, whereas chromothripsis is a ‘genomic catastrophe’ that leads to clustered rearrangements associated with oscillating copy number patterns8. These evolutionary events may occur multiple times at different intensities during tumour development and lead to highly complex cancer genomes9.

Previously, we developed a computational framework that enables the separation of somatic mutations into mutational signatures of single base substitutions (SBSs), doublet base substitutions (DBSs), and small insertions or deletions (IDs)10,11. Analyses of mutational signatures have provided unprecedented insights into the exogenous and endogenous processes that mould cancer genomes at a single nucleotide level12. Prior studies have also examined signatures of genomic rearrangements in cancer, and these have revealed insights into cancer-subtype-specific homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) and templated insertions13,14. Moreover, advancement in the bioinformatics integration of single nucleotide mutations, rearrangements and microsatellite instability profiles have improved signal-to-noise ratios to identify cancer processes15. However, rearrangement signatures can only be derived from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data, which significantly limits their translational usability.

We recently developed a ‘mechanism-agnostic’ approach to summarize allele-specific copy number profiles in whole-genome sequenced sarcomas16, whereby a priori information on the mutational processes active in those cancers was not known, which we term copy number signatures. Other cancer-subtype-specific methods to interrogate copy number patterns that use known hallmarks of genomic instability have been applied to multiple myeloma17, breast cancer18, ovarian cancer19 and prostate cancer20. To our knowledge, there is currently no approach that allows the interrogation of copy number signatures derived from allele-specific profiles across multiple cancer types and across different experimental assays. To address this gap, we developed a new framework to decipher copy number signatures across cancer types (Supplementary Table 1) and multiple experimental platforms.

A framework for copy number signatures

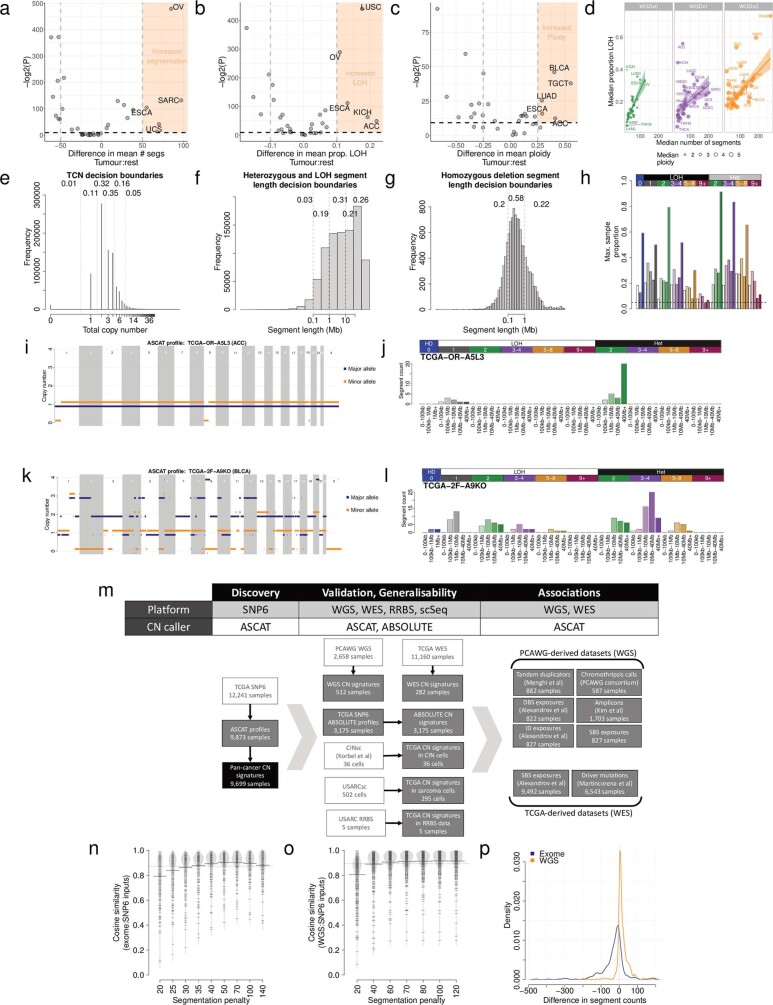

The extent of genomic instability—as measured through the number of copy number segments, the proportion of the genome displaying loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and the status of genome doubling—varied greatly among cancer types in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (Fig. 1a, b). Nevertheless, a linear relationship was observed between the number of segments and the proportion of genomic LOH, which varies from cancers with diploid and copy number ‘quiet’ genomes (for example, acute myeloid leukaemia, thymoma and thyroid carcinoma; Fig. Fig.1a1a and see Supplementary Table 1 for abbreviations of the cancer type) to cancers with highly aberrant copy number profiles (for example, high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas and sarcomas; Extended Data Fig. 1a, b). This linear relationship failed to hold only for adrenocortical carcinoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, both of which demonstrated enrichment of LOH without enrichment of copy number segmentation (Extended Data Fig. 1a–c). In addition, considerable variability of ploidy was observed both between and within cancer types (Fig. (Fig.1b1b and Extended Data Fig. Fig.1d).To1d).To distil this copy number heterogeneity and to capture biologically relevant copy number features, we developed a classification framework that encodes the copy number profile of a sample by summarizing the counts of segments into a 48-dimensional vector on the basis of the total copy number (TCN), the heterozygosity status and the segment size (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 1e–l).

a, Median number of segments in a copy number (CN) profile (x axis), median proportion of the genome that shows LOH (y

axis), median proportion of the genome that shows LOH (y axis) and the proportion of samples that have undergone one or more WGD events (size). The line of best fit from a robust linear regression is shown, whereby the colour of points indicates the weight of the tumour type in the regression model. Error bands indicate the 95% confidence interval, n = 33, t = 4.95, P = 2.5e-5. See Supplementary Table 1 for cancer type abbreviations. b, Ploidy characteristics of all samples split by tumour type. Bottom, ploidy (y

axis) and the proportion of samples that have undergone one or more WGD events (size). The line of best fit from a robust linear regression is shown, whereby the colour of points indicates the weight of the tumour type in the regression model. Error bands indicate the 95% confidence interval, n = 33, t = 4.95, P = 2.5e-5. See Supplementary Table 1 for cancer type abbreviations. b, Ploidy characteristics of all samples split by tumour type. Bottom, ploidy (y axis) for each sample in a tumour type (x

axis) for each sample in a tumour type (x axis), whereby samples are coloured by their genome doubling status as follows: 0×WGD, non-genome-doubled (green); 1×WGD, genome doubled (purple); and 2×WGD, twice genome-doubled (orange). Top, proportion (Prop.) of samples in each tumour type that are 0, 1 or 2×WGD. Horizontal lines indicate median ploidies. c, Decomposition plots of 21 pan-cancer copy number signatures (CN1–CN21). Heterozygosity (Het) status and total copy number (0–9+) are indicated below each column. Segment sizes are shown on the bottom right. Increasing saturation of colour indicates increasing segment size.

axis), whereby samples are coloured by their genome doubling status as follows: 0×WGD, non-genome-doubled (green); 1×WGD, genome doubled (purple); and 2×WGD, twice genome-doubled (orange). Top, proportion (Prop.) of samples in each tumour type that are 0, 1 or 2×WGD. Horizontal lines indicate median ploidies. c, Decomposition plots of 21 pan-cancer copy number signatures (CN1–CN21). Heterozygosity (Het) status and total copy number (0–9+) are indicated below each column. Segment sizes are shown on the bottom right. Increasing saturation of colour indicates increasing segment size.

a) Enrichment of segment counts in TCGA tumour types: x-axis=difference in mean segment counts between tumour type and all other tumours, y-axis=-log2(P-value) from a two-sided Mann-Whitney test. b) Enrichment of LOH in TCGA tumour types: x-axis=difference in mean proportion of genome LOH between tumour type and all other tumours, y-axis=-log2(P-value) from a two-sided Mann-Whitney test. c) Enrichment of high ploidy in TCGA tumour types: x-axis=difference in mean ploidy between tumour type and all other tumours, y-axis=-log2(P-value) from a two-sided Mann-Whitney test. d) Relationship between median number of segments (x-axis), median proportion of the genome that is LOH (y-axis) and ploidy (size) of 33 cancer types in TCGA, split by genome doubling status (panels). Error bands indicate the 95% confidence interval. e) Distribution of total copy number across TCGA. Dashed lines indicate decision boundaries between copy number classes. Numbers indicate the proportion of segments across TCGA that fall within the designated category. f) Maximum proportion of segments (y-axis) of each copy number category (x-axis) in any sample across TCGA. Increasing colour saturation indicates increasing segment length. g) Allele-specific copy number profile from a majority diploid sample (sample ID: TCGA-OR-A5L3, tumour type: ACC). Copy number (y-axis) across the genome (x-axis) is given for both the major (blue) and minor (orange) allele. i) Allele-specific copy number profile for a highly copy number aberrant sample (sample ID: TCGA-2F-A9KO, tumour type: BLCA). j) Copy number summary for TCGA-2F-A9KO. k) Overview of the discovery and validation datasets and samples used to develop the pan-cancer copy number signatures. Raw sequencing or array datasets that were used to generate copy number profiles are shown in white, previously processed datasets are shown in grey, and the pan-cancer copy number signature dataset is shown in black. WGS=whole genome sequencing, WES=whole exome sequencing, RRBS=reduced representation bisulfite sequencing, scSeq=single cell DNA sequencing. Throughout, samples have been excluded from analysis for data quality reasons, and to ensure sample matching between disparate datasets (see Methods for full details). l) Cosine similarity (y-axis) between input copy number summary vectors for exome sequencing and SNP6 array derived copy number profiles. m) Cosine similarity (y-axis) between input copy number summary vectors for whole genome sequencing and SNP6 array derived copy number profiles. n) Difference in segment counts between SNP6 array copy number profiles and whole genome sequencing (orange) or exome sequencing (blue) copy number profiles.

To ensure the generalizability of our framework across platforms, we optimized the copy number calling strategy for each platform, which yielded a strong concordance of summary vectors between WGS, whole-exome sequencing (WES) and SNP6-profiling-derived copy number profiles (Extended Data Fig. 1m–p, Supplementary Table 1 and Methods).

Repertoire of copy number signatures

Copy number matrices (n =

= 9,873; Supplementary Table 1) were decomposed using our previously established and extensively validated approach for deriving a reference set of signatures10,11 (Methods). This approach enabled the identification of both the shared patterns of copy number across all examined samples and the quantification of the number of segments attributed to each copy number signature in each sample, which we termed ‘signature attribution’.

9,873; Supplementary Table 1) were decomposed using our previously established and extensively validated approach for deriving a reference set of signatures10,11 (Methods). This approach enabled the identification of both the shared patterns of copy number across all examined samples and the quantification of the number of segments attributed to each copy number signature in each sample, which we termed ‘signature attribution’.

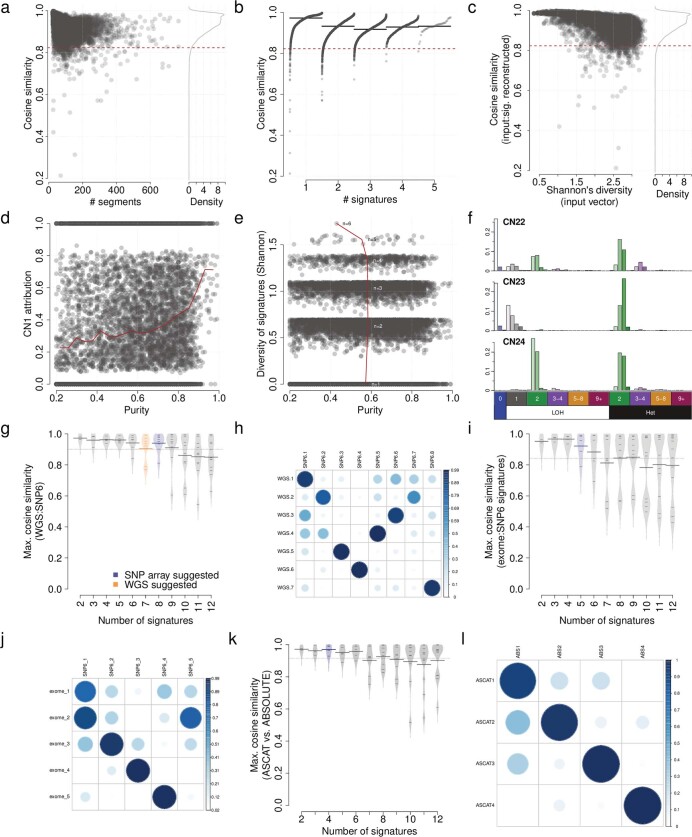

In this first iteration (Methods), we identified 21 distinct pan-cancer signatures (Fig. (Fig.1c1c and Supplementary Table 2). These signatures accurately reconstructed the copy number profiles of 97% of the examined TCGA samples (q value

value <

< 0.05; Methods). The remaining 3% were poorly reconstructed owing to a combination of a low number of segments and/or a high diversity of copy number states in the copy number profile or few operative signatures identified, and are unrelated to purity estimates (Extended Data Fig. 2a–e). The 21 copy number signatures (CN1–CN21) were carefully inspected and categorized into six groups on the basis of their most prevalent features. CN1 and CN2 are primarily defined by >40

0.05; Methods). The remaining 3% were poorly reconstructed owing to a combination of a low number of segments and/or a high diversity of copy number states in the copy number profile or few operative signatures identified, and are unrelated to purity estimates (Extended Data Fig. 2a–e). The 21 copy number signatures (CN1–CN21) were carefully inspected and categorized into six groups on the basis of their most prevalent features. CN1 and CN2 are primarily defined by >40 Mb heterozygous segments with TCNs of 2 and 3–4 respectively. CN3 is characterized by heterozygous segments with sizes >1

Mb heterozygous segments with TCNs of 2 and 3–4 respectively. CN3 is characterized by heterozygous segments with sizes >1 Mb and TCNs between 5 and 8. CN4–CN8 each have segment sizes between 100

Mb and TCNs between 5 and 8. CN4–CN8 each have segment sizes between 100 kb and 10

kb and 10 Mb but with different TCN or LOH states. CN9–CN12 each have numerous LOH components with segment sizes <40

Mb but with different TCN or LOH states. CN9–CN12 each have numerous LOH components with segment sizes <40 Mb. CN13–CN16 have whole-arm-scale or whole-chromosome-scale LOH events (>40

Mb. CN13–CN16 have whole-arm-scale or whole-chromosome-scale LOH events (>40 Mb). CN17 consists of LOH segments with TCNs between 2 and 4 as well as heterozygous segments with TCNs between 3 and 8, each with segment sizes 1–40

Mb). CN17 consists of LOH segments with TCNs between 2 and 4 as well as heterozygous segments with TCNs between 3 and 8, each with segment sizes 1–40 Mb. CN18–CN21 exhibit complex patterns of copy number alterations that are uncommon but are seen in distinct cancer types. In addition, three signatures (CN22–CN24) indicative of copy number profile oversegmentation were identified (Extended Data Fig. Fig.2f2f).

Mb. CN18–CN21 exhibit complex patterns of copy number alterations that are uncommon but are seen in distinct cancer types. In addition, three signatures (CN22–CN24) indicative of copy number profile oversegmentation were identified (Extended Data Fig. Fig.2f2f).

a) Cosine similarity between input copy number 48 dimensional vectors, and signature reconstructed 48 dimensional vectors (y-axis) against number of segments in each copy number profile (x-axis). Dashed line indicates cosine similarity threshold for non-random similarity (P <

< 0.05). b) Cosine similarity between input copy number 48 dimensional vectors, and signature reconstructed 48 dimensional vectors (y-axis) against the number of signatures assigned in each sample (x-axis). Dashed line indicates cosine similarity threshold for non-random similarity (P

0.05). b) Cosine similarity between input copy number 48 dimensional vectors, and signature reconstructed 48 dimensional vectors (y-axis) against the number of signatures assigned in each sample (x-axis). Dashed line indicates cosine similarity threshold for non-random similarity (P <

< 0.05). Solid lines indicate median cosine similarity. The number of signatures is plotted offset by the quantile of the sample. c) Cosine similarity between input copy number 48 dimensional vectors, and signature reconstructed 48 dimensional vectors (y-axis) against the Shannon’s diversity of copy number states in input 48 dimensional vector (x-axis). Dashed line indicates cosine similarity threshold for non-random similarity (P

0.05). Solid lines indicate median cosine similarity. The number of signatures is plotted offset by the quantile of the sample. c) Cosine similarity between input copy number 48 dimensional vectors, and signature reconstructed 48 dimensional vectors (y-axis) against the Shannon’s diversity of copy number states in input 48 dimensional vector (x-axis). Dashed line indicates cosine similarity threshold for non-random similarity (P <

< 0.05). d) Relationship between tumour purity (x-axis) and CN1 attribution (y-axis). If purity was a confounding factor for copy number calling, purity would be positively associated with CN1 attribution due to a reduced power to call copy number alterations, however, the opposite relationship is seen here. e) Relationship between tumour purity (x-axis) and Shannon’s diversity of attributed copy number signatures (y-axis). If purity was a confounding factor for copy number calling, purity might be expected to negatively associate with diversity due to reduced power to call copy number alterations, however, no such association is seen here. f) Three artefactual signatures identified in the TCGA pan-cancer analysis. Artefactual signatures are typified by a large number of homozygous deletions (top two), or small segment sizes of equal copy number in LOH and heterozygous segments (bottom). g) Maximum cosine similarities between each WGS signature and any SNP6 identified signatures (i.e. closest matching signature cosine similarity, y-axis) from 512 samples, with varying numbers of signatures decomposed (x-axis). h) Cosine similarities between WGS (x-axis) and SNP6 (y-axis) identified signatures from 512 samples, with a segmentation penalty of 70. i) Maximum cosine similarities between each exome signature and any SNP6 identified signatures (i.e. closest matching signature cosine similarity, y-axis) from 282 samples, with varying numbers of signatures decomposed (x-axis). j) Cosine similarities between exome and SNP6 identified signatures from 282 samples, with a segmentation penalty of 70 and suggested number of signatures extracted. k) Maximum cosine similarities between each ABSOLUTE-derived signature and any ASCAT-derived signatures (i.e. closest matching signature cosine similarity, y-axis) from 3,175 samples, with varying numbers of signatures decomposed (x-axis). l) Cosine similarities between ABSOLUTE-derived and ASCAT-derived signatures from 3,175 samples, with four signatures extracted in each dataset.

0.05). d) Relationship between tumour purity (x-axis) and CN1 attribution (y-axis). If purity was a confounding factor for copy number calling, purity would be positively associated with CN1 attribution due to a reduced power to call copy number alterations, however, the opposite relationship is seen here. e) Relationship between tumour purity (x-axis) and Shannon’s diversity of attributed copy number signatures (y-axis). If purity was a confounding factor for copy number calling, purity might be expected to negatively associate with diversity due to reduced power to call copy number alterations, however, no such association is seen here. f) Three artefactual signatures identified in the TCGA pan-cancer analysis. Artefactual signatures are typified by a large number of homozygous deletions (top two), or small segment sizes of equal copy number in LOH and heterozygous segments (bottom). g) Maximum cosine similarities between each WGS signature and any SNP6 identified signatures (i.e. closest matching signature cosine similarity, y-axis) from 512 samples, with varying numbers of signatures decomposed (x-axis). h) Cosine similarities between WGS (x-axis) and SNP6 (y-axis) identified signatures from 512 samples, with a segmentation penalty of 70. i) Maximum cosine similarities between each exome signature and any SNP6 identified signatures (i.e. closest matching signature cosine similarity, y-axis) from 282 samples, with varying numbers of signatures decomposed (x-axis). j) Cosine similarities between exome and SNP6 identified signatures from 282 samples, with a segmentation penalty of 70 and suggested number of signatures extracted. k) Maximum cosine similarities between each ABSOLUTE-derived signature and any ASCAT-derived signatures (i.e. closest matching signature cosine similarity, y-axis) from 3,175 samples, with varying numbers of signatures decomposed (x-axis). l) Cosine similarities between ABSOLUTE-derived and ASCAT-derived signatures from 3,175 samples, with four signatures extracted in each dataset.

We also systematically examined copy number signatures derived from WGS, WES and SNP6 profiles of the same samples. The results from this analysis demonstrated a strong concordance between signatures identified through different platforms (median cosine similarity of >0.8) (Extended Data Figs. Figs.1m1m and 2g–j, and Supplementary Table 2) and different copy number callers (median cosine similarity of 0.98) (Extended Data Fig. 2k–l and Supplementary Table 2).

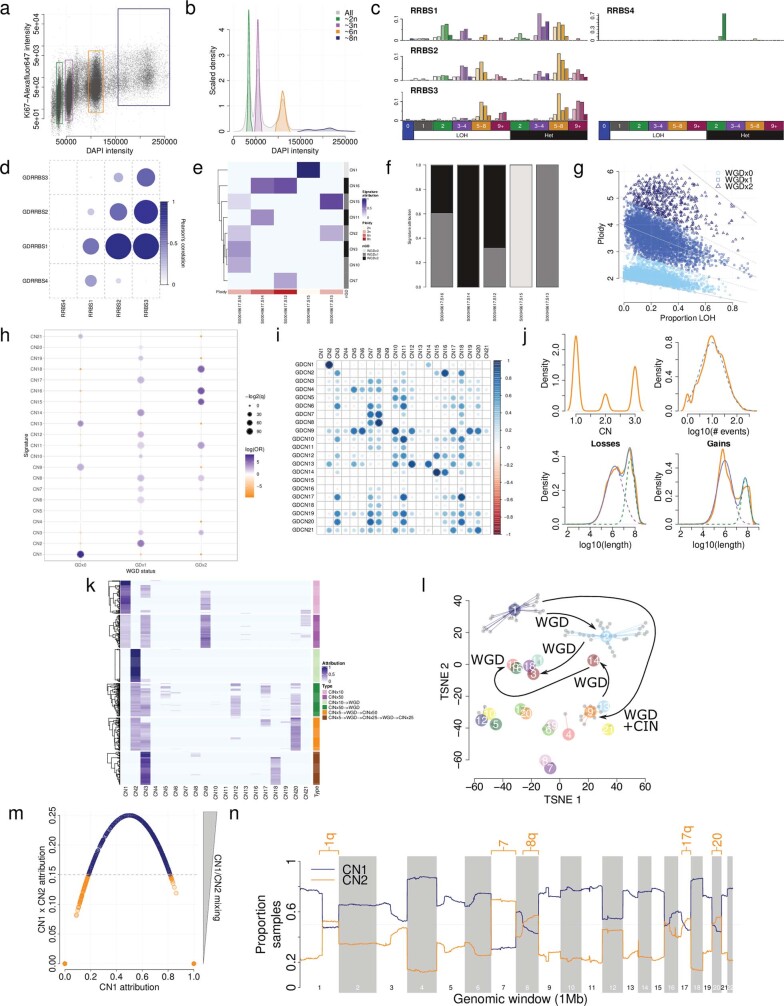

Transitional nature of copy number signatures

The catalogue of somatic mutations in a cancer genome is the cumulative result of the mutational processes that have been operative over the lifetime of the cell of origin21. Analyses of SBS and ID mutational signatures have used assumptions and prior evidence that individual mutations are independent and additive12. However, this assumption is violated for large-scale macro-evolutionary events such as WGD22. Moreover, there are inherent challenges in inferring WGD using copy number calling algorithms that affect subclonal tumour reconstruction23. We therefore generated several synergistic lines of evidence to investigate the impact of WGD on copy number signatures. First, we undertook copy number profiling of experimentally ploidy-sorted populations of undifferentiated soft tissue sarcoma (Supplementary Table 3 and Extended Data Fig. 3a–f). Second, each copy number signature was tested for enrichment in non-, once- or twice-genome doubled samples (Extended Data Fig. 3g, h and Supplementary Table 3). Third, in silico simulations of genome doubling on the extracted signatures were performed (Methods, Extended Data Fig. Fig.3i3i and Supplementary Table 3). Fourth, copy number profiles arising from dynamics of WGD and chromosomal instability (CIN) were simulated (Extended Data Fig. Fig.3j)3j) and re-examined for the previously derived signatures (Extended Data Fig. Fig.3k3k and Supplementary Table 3).

a) Flow cytometry sorting of cells based on staining of DAPI (x-axis) as a proxy for DNA content and ki67 staining (y-axis) as a marker of proliferation. Cells were gated for sorting according to coloured boxes shown. b) Density of cells from flow sorting shown for all cells (grey) and for individual sorted populations of cells (coloured). c) De-novo signatures extracted from ploidy-sorted populations of cells profiled with reduced representation bisulfite sequencing. d) Cosine similarities between de-novo signatures and artificially genome- doubled versions of those signatures. Signature C has the highest similarity with genome doubled signature A, and signature B has the highest similarity with genome doubled signature C, indicating successive genome doublings leading to transitions of signatures. e) Attribution (blue) of pan-cancer signatures (y-axis) across ploidy-sorted populations of cells (x-axis). Ploidy of the sorted population is shown in red. Genome-doubling association of the pan-cancer signatures is shown in grayscale. f) Summed attribution of genome-doubling classifications of pan-cancer signatures across ploidy-sorted populations of cells. g) WGD calls for TCGA, based on ploidy and the proportion of the genome that is LOH. See Methods for details. WGDx0=non-genome doubled, WGDx1=genome doubled once, WGDx2=twice genome doubled. h) Associations between copy number signature exposure and WGD calls. GDx0=non-genome doubled, GDx1=genome doubled once, GDx2=twice genome doubled. i) Cosine similarities between signatures (CN1-21) and their artificially genome doubled counterparts (GDCN1-21). A high cosine similarity between e.g. CN2 and GDCN1 indicated that CN2 is a genome doubled version of CN1. j) Distributions of total copy number of segments (only TCN1-3, top-left), number of non-diploid segements (top-right), segment length of losses (TCN=1, bottom-left) and segment length of gains (TCN=3, bottom-right) for predominantly diploid (CN1+9>0.8) profiles in TCGA. Orange lines indicate empirical distributions, non-orange lines indicate simulated distributions. Dashed lines indicate components of mixture distributions, or the distribution for non-mixed distributions. Solid blue lines indicate joint distributions. k) Attributions (blue) of the 21 pan-cancer signatures (x-axis) in 6 simulation designs each of 100 samples (y-axis). CIN=random sub-chromosomal copy number gain or loss. WGD=whole genome doubling. l) TSNE representation of all non-artefactual signatures (coloured points). Inferences about the relationships between signatures (Extended Data Fig. 3) are indicated with arrows; WGD=whole-genome doubling, CIN=chromosomal instability. m) CN1 attribution (x-axis) against CN1 attribution × CN2 attribution in samples for which CN1+CN2 attribution = 1. Decision boundary for determining highly aneuploid samples is shown in grey. Orange points are taken for further analysis of aneuploidy. n) CN1 (blue) and CN2 (orange) recurrence (y-axis) across the genome (x-axis) in 472 highly aneuploid samples where CN1+CN2 attribution = 1. Chromosome arms with >50% samples attributed to CN2 are labelled.

By combining the preceding set of in silico simulations and wet-laboratory experiments, we confirmed the transitional nature of copy number signatures, with one signature being completely effaced by another after WGD (Extended Data Fig. Fig.3l).3l). In this model, a cancer with a diploid signature (CN1), may undergo WGD, which alters the signature CN1 into signature CN2. Alternatively, a cancer may show a CIN-transforming signature of CN1 into signature CN9. Through a combination of CIN and WGD, signature CN2 may transform into signature CN3. Meanwhile, CN13–CN15 are linked through successive WGD events on the background of early chromosomal losses.

Although WGD has a transitional effect on copy number signatures, we hypothesized that smaller scale events, such as segmental aneuploidy, may reflect additive behaviour similar to mutational signatures. To investigate this, we focused on the ploidy-associated signatures CN1 (diploid) and CN2 (tetraploid), for which an attribution of both signatures together indicates a hyperdiploid or subtetraploid profile (Extended Data Fig. Fig.3m3m and Supplementary Table 3). We mapped these signatures across the cancer genomes so that only CN1 and CN2 were attributed (CN1 +

+ CN2

CN2 =

= 1) and had a mixed attribution of those signatures (CN1

1) and had a mixed attribution of those signatures (CN1 ×

× CN2

CN2 >

> 0.15). This analysis recapitulated known patterns of aneuploidy in human cancer24, including gains of chromosomes 1q, 7, 8q, 16p, 17q and 20 in more than 50% of TCGA samples (Extended Data Fig. Fig.3n3n).

0.15). This analysis recapitulated known patterns of aneuploidy in human cancer24, including gains of chromosomes 1q, 7, 8q, 16p, 17q and 20 in more than 50% of TCGA samples (Extended Data Fig. Fig.3n3n).

The landscape of copy number signatures

Next, we surveyed the distribution of the 21 signatures across different cancer types (Fig. (Fig.22 and Supplementary Table 4). The ploidy-associated signatures CN1 and CN2 were found in most samples across all cancer types. Signatures CN4, CN7, CN10, CN18, CN20 and CN21 were derived through specific cancer type extractions and therefore unique to uveal melanoma, breast cancer, lung squamous carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma, liver cancer and paragangliomas, respectively. Signatures CN4–CN8 all showed segments of high TCNs and were seen in tumour types with known prevalent amplicon events25. CN9–CN12 showed differing patterns of hypodiploidy, with segment sizes of LOH <

< 40

40 Mb and WGD that was reflective of a type of structural CIN often induced by replication stress26. Signatures CN14 and CN16 were prevalent in adrenocortical carcinoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, which indicates a link with the known patterns of chromosomal-scale LOH (cLOH) seen in these cancers27,28. Signature CN17 was prevalent in tumour types previously described as being HRD and enriched in the tandem duplicator phenotype (TDP)29. Different cancer lineages clustered together on the basis of the prevalence of signatures; namely TDP, WGD, diploid CIN, simple diploidy and cLOH (Fig. (Fig.2).2). This segregation of cancer types and their constituent signatures reflects the genomic heterogeneity imparted through WGD, chromothripsis and aneuploidy in human cancer5,7.

Mb and WGD that was reflective of a type of structural CIN often induced by replication stress26. Signatures CN14 and CN16 were prevalent in adrenocortical carcinoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, which indicates a link with the known patterns of chromosomal-scale LOH (cLOH) seen in these cancers27,28. Signature CN17 was prevalent in tumour types previously described as being HRD and enriched in the tandem duplicator phenotype (TDP)29. Different cancer lineages clustered together on the basis of the prevalence of signatures; namely TDP, WGD, diploid CIN, simple diploidy and cLOH (Fig. (Fig.2).2). This segregation of cancer types and their constituent signatures reflects the genomic heterogeneity imparted through WGD, chromothripsis and aneuploidy in human cancer5,7.

Attributions of the 21 signatures (y axis) split by tumour type (x

axis) split by tumour type (x axis). The size of each dot represents the proportion of samples of each tumour type that shows the signature and the colour reflects the median attribution of the signature in each tumour type. Tumour/signature attributions with less than 5% of samples are not shown. Hierarchical clustering is shown below, sample sizes are shown above. aCN15 was identified from an extraction of high LOH samples (>70% of the genome LOH), and is not found at ≥5% frequency in any tumour type. bCN4 was identified in UVM at <5% frequency. Het mix, mixture of heterozygous segments.

axis). The size of each dot represents the proportion of samples of each tumour type that shows the signature and the colour reflects the median attribution of the signature in each tumour type. Tumour/signature attributions with less than 5% of samples are not shown. Hierarchical clustering is shown below, sample sizes are shown above. aCN15 was identified from an extraction of high LOH samples (>70% of the genome LOH), and is not found at ≥5% frequency in any tumour type. bCN4 was identified in UVM at <5% frequency. Het mix, mixture of heterozygous segments.

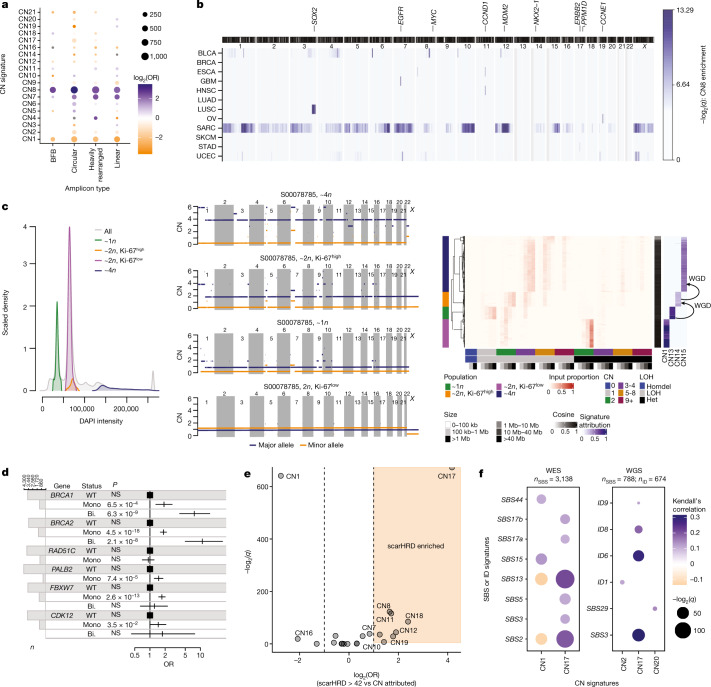

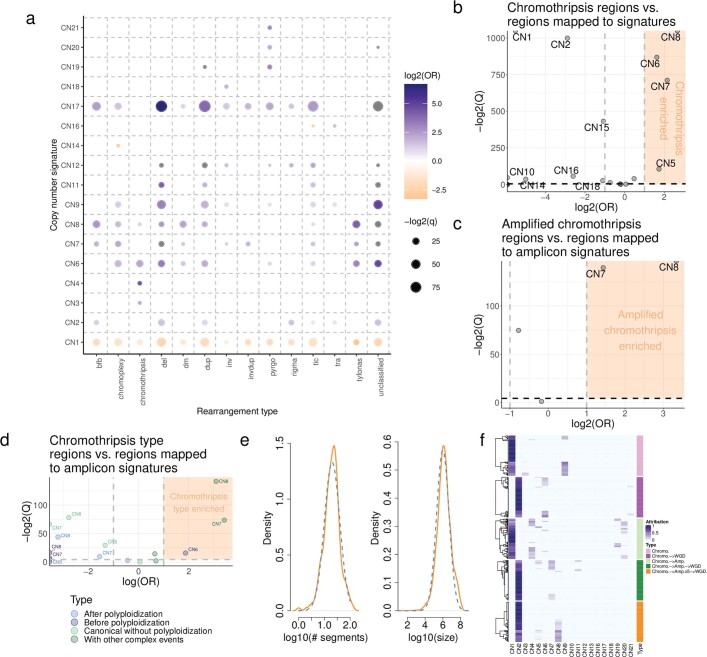

Signatures associated with chromothripsis

Oncogene amplification is associated with aggressive behaviour in cancer25. Reasoning that signatures with high levels of TCN (CN4–CN8) could be associated with genomic amplification, we correlated these signatures with known classes of amplicons25,30. All amplicon signatures were positively associated with one or more amplicon types (Fig. (Fig.3a3a and Extended Data Fig. Fig.4).4). CN8, which shows very high copy number states and is enriched in nine cancer types (two-sided Mann–Whitney test, q <

< 0.05), was strongly associated with all four classes of amplicons, although most strongly with extra-chromosomal circular DNA amplicons (ecDNA) and the recently described large amplicon phenotype termed ‘tyfonas’31 (Extended Data Fig. Fig.4a4a).

0.05), was strongly associated with all four classes of amplicons, although most strongly with extra-chromosomal circular DNA amplicons (ecDNA) and the recently described large amplicon phenotype termed ‘tyfonas’31 (Extended Data Fig. Fig.4a4a).

a, Associations between signatures (y axis) and amplicon structures (x

axis) and amplicon structures (x axis), displaying the q

axis), displaying the q value (size) and log2(OR) (colour) from two-sided Fisher’s exact tests of genomic regions unattributed or attributed to each signature against each amplicon type. Only significant (q

value (size) and log2(OR) (colour) from two-sided Fisher’s exact tests of genomic regions unattributed or attributed to each signature against each amplicon type. Only significant (q <

< 0.05) associations are shown. BFB, breakage–fusion–bridge. b, Enrichment of mapped CN8 in 1-Mb windows of the human genome across 8 cancer types in which ≥40 samples were attributed CN8. Colour indicates the –log2(q

0.05) associations are shown. BFB, breakage–fusion–bridge. b, Enrichment of mapped CN8 in 1-Mb windows of the human genome across 8 cancer types in which ≥40 samples were attributed CN8. Colour indicates the –log2(q value) from a bootstrapping analysis to determine significance. An ideogram of chromosome bands is shown above. c, Single-cell sequencing from a near-genome-wide LOH undifferentiated soft tissue sarcoma. Sorted populations of cells based on ploidy and proliferation (left) were single-cell sequenced and copy number profiled (middle, representative cells). Copy number (y

value) from a bootstrapping analysis to determine significance. An ideogram of chromosome bands is shown above. c, Single-cell sequencing from a near-genome-wide LOH undifferentiated soft tissue sarcoma. Sorted populations of cells based on ploidy and proliferation (left) were single-cell sequenced and copy number profiled (middle, representative cells). Copy number (y axis) across the genome (x

axis) across the genome (x axis) is given for both the major (blue) and minor (orange) allele. Copy number summaries (red) and signatures (blue) recapitulate the pattern seen in the copy number profiles (right). d, Association between mutational status of key HR pathway genes and CN17 attribution from a multivariate two-sided logistic regression model including cancer type as a covariate. NS, not significant (P

axis) is given for both the major (blue) and minor (orange) allele. Copy number summaries (red) and signatures (blue) recapitulate the pattern seen in the copy number profiles (right). d, Association between mutational status of key HR pathway genes and CN17 attribution from a multivariate two-sided logistic regression model including cancer type as a covariate. NS, not significant (P ≥

≥ 0.05). Squares represent point estimates for the odds ratio (OR). Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. n

0.05). Squares represent point estimates for the odds ratio (OR). Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. n =

= 4,919 biologically independent tumours. Bi., bi-allelic alteration; Mono., monoallelic alteration; WT, wild type. e, Association between signature attribution and scarHRD score, an orthogonal test for HRD, displaying –log2(q) (y

4,919 biologically independent tumours. Bi., bi-allelic alteration; Mono., monoallelic alteration; WT, wild type. e, Association between signature attribution and scarHRD score, an orthogonal test for HRD, displaying –log2(q) (y axis) and log2(OR) (x

axis) and log2(OR) (x axis) from two-sided Fisher’s exact tests in which scarHRD positivity was based on a threshold of >42. A half dot indicates an infinite –log2(q

axis) from two-sided Fisher’s exact tests in which scarHRD positivity was based on a threshold of >42. A half dot indicates an infinite –log2(q value) (q

value) (q =

= 0). f, Correlation between copy number signature (x

0). f, Correlation between copy number signature (x axis) attribution and SBS or ID signature (y

axis) attribution and SBS or ID signature (y axis) exposure across TCGA exomes (left) and whole genomes (right). The strength of correlation is indicated by colour (orange, anticorrelated, blue, correlated), the q

axis) exposure across TCGA exomes (left) and whole genomes (right). The strength of correlation is indicated by colour (orange, anticorrelated, blue, correlated), the q value is indicated by point size. Non-significant (q

value is indicated by point size. Non-significant (q >

> 0.01) associations are not shown.

0.01) associations are not shown.

a) Associations between copy number signature attribution (y-axis) and rearrangement phenomena (x-axis) described in Hadi et al. (2020). Effect size (log2 odds ratio, colour), and significance level (-log2 Q-value, size) from a Fisher’s exact test are displayed. b) Correlation between copy number signature attributed segments and chromothriptic regions at a genomic level. X-axis=effect size (log odds ratio), y-axis=significance (-log2 Q-value). A half dot indicates an infinite value (Q =

= 0, or OR=Inf). c) Same as for (a), but correlated against amplified chromothripsis. CN7-8 OR= OR

0, or OR=Inf). c) Same as for (a), but correlated against amplified chromothripsis. CN7-8 OR= OR =

= 2.69 and 10.08 respectively, Q

2.69 and 10.08 respectively, Q <

< 0.05. d) Same as for (a), but correlated against distinct chromothripsis types. e) Distributions of the number of segments (left) and segment sizes (right) on chromothriptic chromosomes identified by PCAWG. Orange lines indicate empirical distributions. Blue dashed lines indicate simulation distributions. f) Attributions (blue) of the 21 pan-cancer signatures (x-axis) in 5 simulation designs each of 100 samples (y-axis). Chromo.=chromothripsis. WGD=whole genome doubling. Amp=single gain of the derivative chromothriptic chromosome.

0.05. d) Same as for (a), but correlated against distinct chromothripsis types. e) Distributions of the number of segments (left) and segment sizes (right) on chromothriptic chromosomes identified by PCAWG. Orange lines indicate empirical distributions. Blue dashed lines indicate simulation distributions. f) Attributions (blue) of the 21 pan-cancer signatures (x-axis) in 5 simulation designs each of 100 samples (y-axis). Chromo.=chromothripsis. WGD=whole genome doubling. Amp=single gain of the derivative chromothriptic chromosome.

Recent evidence shows that genomic amplification can evolve through inter-related processes of chromothripsis, breakage–fusion–bridge and ecDNA formation32. To test this finding, we mapped the copy number signatures with known regions of chromothripsis33 across the cancer genome (Methods), which revealed that CN5–CN8 are enriched in chromothriptic regions (Extended Data Fig. Fig.4b4b and Supplementary Table 5). Each of these signatures was dominated by small segments, while CN7 and CN8 were both strongly associated with amplified chromothripsis33 (Extended Data Fig. Fig.4c),4c), larger DNA segments and complex chromothriptic events (Extended Data Fig. Fig.4d).4d). Simulations of copy number profiles incorporating processes of chromothripsis, WGD and chromosomal duplication (Extended Data Fig. Fig.4e)4e) demonstrated that CN4–CN8 can be generated through chromothripsis-like events. Moreover, these signatures reflected distinct life histories of tumours, such as chromothripsis before or after WGD (Extended Data Fig. 4d, f and Supplementary Table 5).

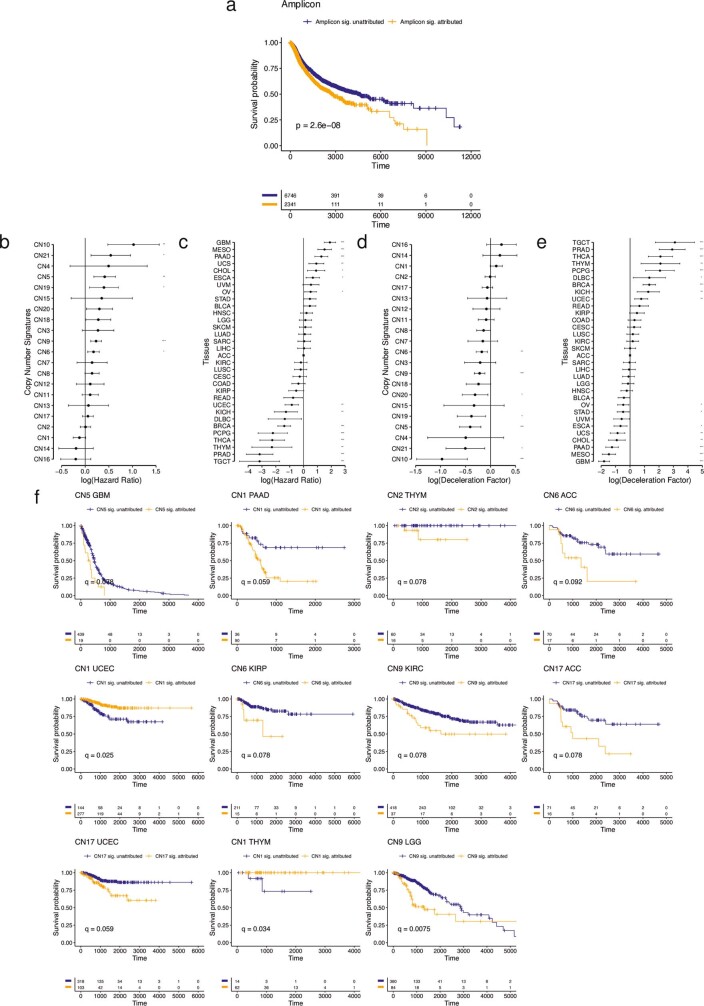

Chromothripsis and gene amplification are both independently associated with poor prognosis25,34. Attribution of any of the five amplicon signatures in their respective cancer types showed poor disease-specific survival in a univariate pan-cancer analysis (Extended Data Fig. Fig.5a5a and Supplementary Table 5). Similarly, multiple amplicon signatures were associated with reduced disease-specific survival in multivariate pan-cancer and cancer subtype analyses, with consistent results from analyses based on Cox-model hazard ratios (Extended Data Fig. 5b, c and Supplementary Table 5) and analyses based on accelerated failure times (Extended Data Fig. 5d, e and Supplementary Table 5). For example, a cancer-type-specific survival analysis revealed that patients with glioblastoma with operative signature CN5 had poor disease-specific survival (172 days reduced median survival; Extended Data Fig. Fig.5f5f and Supplementary Table 5). To determine the topographical localization of the amplification events, we mapped the most common amplicon signature with the highest amplification level, CN8, across the genome in eight cancer types (n

days reduced median survival; Extended Data Fig. Fig.5f5f and Supplementary Table 5). To determine the topographical localization of the amplification events, we mapped the most common amplicon signature with the highest amplification level, CN8, across the genome in eight cancer types (n ≥

≥ 40 in each type) that were attributed CN8, and assessed CN8 enrichment in each cancer type through a bootstrapping analysis. This revealed cancer-type-specific enrichment of CN8 in regions harbouring oncogenes that are commonly amplified in their respective cancer types (Fig. (Fig.3b3b and Supplementary Table 5).

40 in each type) that were attributed CN8, and assessed CN8 enrichment in each cancer type through a bootstrapping analysis. This revealed cancer-type-specific enrichment of CN8 in regions harbouring oncogenes that are commonly amplified in their respective cancer types (Fig. (Fig.3b3b and Supplementary Table 5).

a) Kaplan-Meier curves of disease specific survival for patients whose tumours are amplicon signature (CN4:8) attributed (orange) and non-attributed (blue). b) Cox-model hazard ratios (x-axis) for copy number signatures (y-axis) with copy number signature attribution and tumour type as a covariates (see Extended Data Fig. 5e). Horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Sample sizes are given in Supplementary Table 5. c) Cox-model hazard ratios (x-axis) for tumour types (y-axis) with copy number signature attribution (see Extended Data Fig. 5d) and tumour type as covariates. Horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. ACC is taken as the reference tumour type (square point). d) Accelerated failure time deceleration factors (x-axis) for copy number signatures (y-axis) with copy number signature attribution and tumour type as a covariates (see Extended Data Fig. 5c). A log(deceleration factor)<1 indicates reduced survival time (accelerated failure time), while a log(deceleration factor)>1 indicates increased survival time (deaccelerated failure time). Horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Sample sizes are given in Supplementary Table 5. e) Accelerated failure time deceleration factors (x-axis) for tumour types (y-axis) with copy number signature attribution (see Extended Data Fig. 5b) and tumour type as covariates. A log(deceleration factor)<1 indicates reduced survival time (accelerated failure time), while a log(deceleration factor)>1 indicates increased survival time (deaccelerated failure time). Horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. ACC is taken as the reference tumour type (square point). f) Kaplan-Meier curves for within-tumour type associations with copy number signature attribution. Tumour type/copy number signature combinations with a significant effect on survival (Q <

< 0.05) are displayed.

0.05) are displayed.

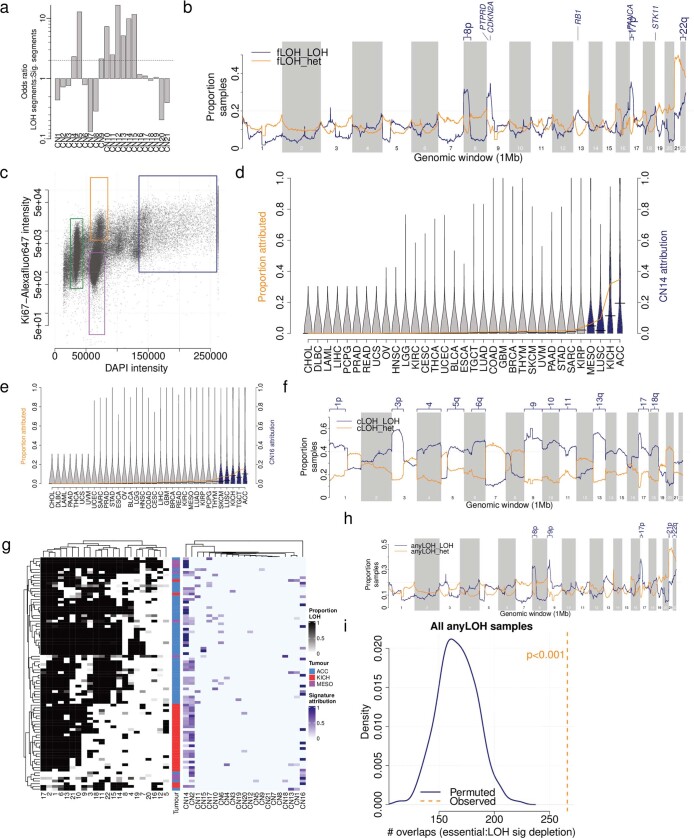

Signatures associated with LOH

LOH is an important mechanism that contributes to the inactivation of tumour suppressor genes during cancer development6,33,35. Nine signatures were positively correlated with LOH regions of the genome (Extended Data Fig. Fig.6a)6a) and were recurrently found around known tumour suppressor genes (Extended Data Fig. Fig.6b6b and Supplementary Table 6). Four of these signatures (CN9–CN12) exhibited predominantly small segment sizes and very few that were >40 Mb (Fig. (Fig.1c)1c) and were therefore termed focal LOH (fLOH) signatures.

Mb (Fig. (Fig.1c)1c) and were therefore termed focal LOH (fLOH) signatures.

a) Association between LOH segments and mapped copy number signature segments across the full TCGA cohort. b) Recurrence of mapped LOH signatures (y-axis) across the genome in 1Mb bins (x-axis), split by LOH (blue) or heterozygous (orange) segments. Tumour suppressor genes with >20% of samples with LOH signatures are labelled. c) FACS sorting of undifferentiated sarcoma cells. Cells were gated on DAPI staining intensity (x-axis, proxy for DNA content), and ki67 intensity (y-axis, indicating replicating cells). Gates were chosen to isolate population of near haploid cells (~1n, green), replicating and non- replicating ~2n populations of cells (orange and purple respectively) and a ~4n population of cells (blue). d) Prevalence (orange line) and distribution (violins) of CN14 attributions across TCGA cancer types. Blue violins are cancer types significantly enriched in CN14 compared to all others (Q <

< 0.05, Mann Whitney test). KICH enrichment: OR

0.05, Mann Whitney test). KICH enrichment: OR =

= 4.6, P

4.6, P =

= 3.0e-3, Fisher’s exact test. ACC enrichment: OR

3.0e-3, Fisher’s exact test. ACC enrichment: OR =

= 8.9, P

8.9, P =

= 6.3e-9, Fisher’s exact test. e) Prevalence (orange line) and distribution (violins) of CN16 attributions across TCGA cancer types. Blue violins are cancer types significantly enriched in CN21 compared to all others (Q

6.3e-9, Fisher’s exact test. e) Prevalence (orange line) and distribution (violins) of CN16 attributions across TCGA cancer types. Blue violins are cancer types significantly enriched in CN21 compared to all others (Q <

< 0.05, Mann Whitney test). KICH enrichment: OR

0.05, Mann Whitney test). KICH enrichment: OR =

= 30.5, P

30.5, P =

= 1.0e-21, Fisher’s exact test. ACC enrichment: OR

1.0e-21, Fisher’s exact test. ACC enrichment: OR =

= 37.4, P

37.4, P =

= 3.5e- 33, Fisher’s exact test. f) Recurrence of mapped arm-level LOH signatures (y-axis) across the genome in 1Mb bins (x-axis), split by LOH (blue) or heterozygous (orange) segments. Chromsome arms with >50% of samples with LOH signatures are labelled. g) Left: Heatmap of LOH prevalence by chromosome (x-axis) and sample (y-axis) for all CN13-CN16 attributed ACC, KICH or MESO samples. Samples are clustered according to chromosomal LOH levels. Right: Copy number signature attributions for the same samples. h) Recurrence of mapped chromosomal-scale and focal LOH signatures (y-axis) across the genome in 1Mb bins (x-axis), split by LOH (blue) or heterozygous (orange) segments. Chromosome arms with >20% of samples with LOH signatures are labelled. i) Enrichment of essential genes in regions of the genome with >20% of the samples having heterozygous segments of cLOH or fLOH signatures through bootstrapping of genomic regions.

3.5e- 33, Fisher’s exact test. f) Recurrence of mapped arm-level LOH signatures (y-axis) across the genome in 1Mb bins (x-axis), split by LOH (blue) or heterozygous (orange) segments. Chromsome arms with >50% of samples with LOH signatures are labelled. g) Left: Heatmap of LOH prevalence by chromosome (x-axis) and sample (y-axis) for all CN13-CN16 attributed ACC, KICH or MESO samples. Samples are clustered according to chromosomal LOH levels. Right: Copy number signature attributions for the same samples. h) Recurrence of mapped chromosomal-scale and focal LOH signatures (y-axis) across the genome in 1Mb bins (x-axis), split by LOH (blue) or heterozygous (orange) segments. Chromosome arms with >20% of samples with LOH signatures are labelled. i) Enrichment of essential genes in regions of the genome with >20% of the samples having heterozygous segments of cLOH or fLOH signatures through bootstrapping of genomic regions.

Genome-wide chromosomal-scale losses (near haploidy), often followed by genome doubling, are associated with poor prognosis in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia36. Conversely, haploidization is associated with immune cell infiltration and a relatively better prognosis in undifferentiated soft tissue sarcoma16. This is an uncommon event in cancer (0.2% prevalence in TCGA; Extended Data Fig. Fig.3g)3g) but is seen in as much as 3% of sarcomas and mesotheliomas. We reasoned that this phenomenon could result in a distinctive copy number signature that could have clinical implications. We selectively extracted signatures from cancers that display an LOH of more than 70% of the genome, which revealed the distinctive signatures CN13, CN14 and CN15. We experimentally confirmed these rare signatures through ploidy sorting and single-cell DNA sequencing (SCS) of undifferentiated soft tissue sarcoma (Extended Data Fig. Fig.6c6c and Supplementary Table 6), which are known to have genome-wide LOH and a complex subclonal structure16. These unique signatures were represented in multiple subclones and reflected successive WGDs on a background of genome-wide LOH (Fig. (Fig.3c).3c). Other patterns of distinctive hypodiploidy37,38 were enriched in adrenocortical carcinoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (CN14 and CN16; Extended Data Fig. 6d, e). Mapping of these signatures to the genome displayed recurrent LOH in chromosome regions 1p, 3p, 5q, 9, 10q, 13q and 17p (Extended Data Fig. 6f, g and Supplementary Table 6), which matched known patterns of aneuploidy in these cancers27,28.

An allele-specific deletion of a DNA segment harbouring an essential gene that results in LOH represents a potential therapeutic vulnerability39, and such regions have been shown to be under strong negative selection for deleterious mutations22,40,41. We hypothesized that in cancers with extensive LOH signatures, regions of the genome with a high density of essential genes may show retention of heterozygosity. An enrichment analysis revealed that regions of retained heterozygosity were enriched in essential genes compared with random selections of regions across the genome (Extended Data Fig. 6h, i). These essential-gene-enriched regions are probably subject to strong negative selection for genomic losses and therefore represent a particularly rich area to explore for therapeutics. This is particularly relevant to cancers that have extensive LOH, as tagged here with cLOH signatures in adrenocortical carcinomas, kidney chromophobe cancers and mesotheliomas.

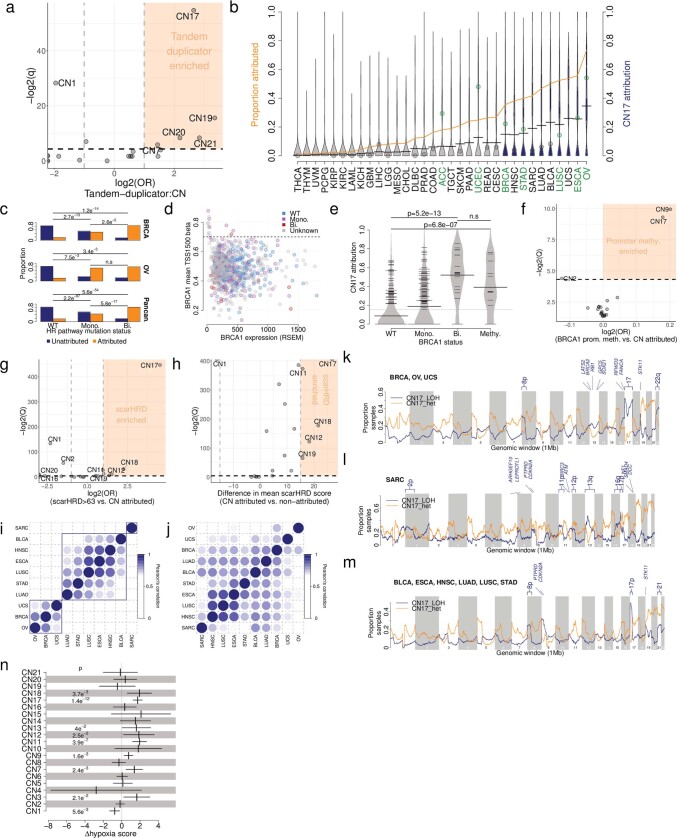

Signatures associated with HRD

Somatic tandem duplications (TDs) are commonly found in breast cancer and ovarian cancer that show failure of homologous recombination (HR) repair of DNA double-strand breaks, for example, owing to defective BRCA1 or BRCA2 expression29,42. A detailed characterization of TD across cancer types has revealed three patterns with duplicated segments that range around 10 kb, 200

kb, 200 kb or 2

kb or 2 Mb (ref. 29). CN17 has a segment size distribution that overlaps with the largest of these three patterns and was strongly associated with TD (Extended Data Fig. Fig.7a7a and Supplementary Table 7; odds ratio (OR)

Mb (ref. 29). CN17 has a segment size distribution that overlaps with the largest of these three patterns and was strongly associated with TD (Extended Data Fig. Fig.7a7a and Supplementary Table 7; odds ratio (OR) =

= 6.3, q

6.3, q =

= 3.6

3.6 ×

× 10–17, two-sided Fisher’s exact test) and enriched in cancer types known to show TD29 (Extended Data Fig. Fig.7b7b).

10–17, two-sided Fisher’s exact test) and enriched in cancer types known to show TD29 (Extended Data Fig. Fig.7b7b).

a) Associations between copy number signature attributed samples and tandem-duplicator phenotype samples, displaying -log2(Q-values) (y-axis) and log2 odds ratios (x-axis). CN17 association: OR =

= 6.3, Q

6.3, Q =

= 3.6e-17, Fisher’s exact test. b) Prevalence (orange line) and distribution (violins) of CN17 attributions across TCGA cancer types. Blue violins are cancer types significantly enriched in CN17 compared to all others (Q

3.6e-17, Fisher’s exact test. b) Prevalence (orange line) and distribution (violins) of CN17 attributions across TCGA cancer types. Blue violins are cancer types significantly enriched in CN17 compared to all others (Q <

< 0.05, Mann Whitney test). Points indicate the prevalence of TDP in given tumour types from the literature (Menghi et al., 2018) coloured by over- (green) or underrepresentation (gray). A half dot indicates an infinite value. c) Correlation of CN17 attribution (y-axis) with mutational status of one or more genes of the homologous recombination pathway (x-axis) in breast cancer (top, n

0.05, Mann Whitney test). Points indicate the prevalence of TDP in given tumour types from the literature (Menghi et al., 2018) coloured by over- (green) or underrepresentation (gray). A half dot indicates an infinite value. c) Correlation of CN17 attribution (y-axis) with mutational status of one or more genes of the homologous recombination pathway (x-axis) in breast cancer (top, n =

= 589), ovarian cancer (middle, n

589), ovarian cancer (middle, n =

= 309) or pan-cancer (bottom, n

309) or pan-cancer (bottom, n =

= 4,919). WT=wild type. Mono = Mono-allelic and Bi = bi-allelic. Two-sided Fisher’s exact test: Q-values are given above, n.s.=Q

4,919). WT=wild type. Mono = Mono-allelic and Bi = bi-allelic. Two-sided Fisher’s exact test: Q-values are given above, n.s.=Q ≥

≥ 0.05. d) Relationship between BRCA1 gene expression (x-axis) and promoter methylation (y-axis). A mean TSS1500 beta cutoff of 0.7 was chosen to indicate promoter hyper-methylation, correlating with gene silencing. e) CN17 attribution (y-axis) split by BRCA1 mutational status (x-axis) in TCGA breast cancers. WT=wild type (n

0.05. d) Relationship between BRCA1 gene expression (x-axis) and promoter methylation (y-axis). A mean TSS1500 beta cutoff of 0.7 was chosen to indicate promoter hyper-methylation, correlating with gene silencing. e) CN17 attribution (y-axis) split by BRCA1 mutational status (x-axis) in TCGA breast cancers. WT=wild type (n =

= 220), Mono.=mono-allelic mutation (n

220), Mono.=mono-allelic mutation (n =

= 148), Bi.=bi-allelic mutation (n

148), Bi.=bi-allelic mutation (n =

= 19), Methy.=promoter hypermethylation (n

19), Methy.=promoter hypermethylation (n =

= 13). Two-sided Mann-Whitney test: P-values are given above, n.s.=P

13). Two-sided Mann-Whitney test: P-values are given above, n.s.=P ≥

≥ 0.05. f) Association between copy number signature attribution and promoter hypermethylation of BRCA1 (beta

0.05. f) Association between copy number signature attribution and promoter hypermethylation of BRCA1 (beta >

> 0.7), displaying -log2(Q-values) (y-axis) and log2 odds ratios (x-axis) from a multivariate logistic regression model with cancer type as a covariate. g) Association between copy number signature attribution and scarHRD score, displaying -log2(Q-values) (y-axis) and log2 odds ratios (x-axis) from a Fisher’s exact test where scarHRD positivity was thresholded at >63. A half dot indicates an infinite value. h) Association between copy number signature attribution and scarHRD score, displaying -log2(Q-values) (y-axis) and difference in mean scarHRD scores (x-axis) from a Mann-Whitney test on continuous scarHRD scores. A half dot indicates an infinite value. i) Pearson’s correlation of recurrence of mapping of LOH segments of CN17 to the genome calculated for all pairwise comparisons of CN17-enriched tumour types. j) Pearson’s correlation of recurrence of mapping of CN17 to the genome from pairwise comparisons of CN17 enriched tumour types for heterozygous segments. k) Recurrence of mapped CN17 in 1

0.7), displaying -log2(Q-values) (y-axis) and log2 odds ratios (x-axis) from a multivariate logistic regression model with cancer type as a covariate. g) Association between copy number signature attribution and scarHRD score, displaying -log2(Q-values) (y-axis) and log2 odds ratios (x-axis) from a Fisher’s exact test where scarHRD positivity was thresholded at >63. A half dot indicates an infinite value. h) Association between copy number signature attribution and scarHRD score, displaying -log2(Q-values) (y-axis) and difference in mean scarHRD scores (x-axis) from a Mann-Whitney test on continuous scarHRD scores. A half dot indicates an infinite value. i) Pearson’s correlation of recurrence of mapping of LOH segments of CN17 to the genome calculated for all pairwise comparisons of CN17-enriched tumour types. j) Pearson’s correlation of recurrence of mapping of CN17 to the genome from pairwise comparisons of CN17 enriched tumour types for heterozygous segments. k) Recurrence of mapped CN17 in 1 Mb windows of the human genome in all CN17 attributed BRCA, OV and UCS samples, split by LOH (blue) and heterozygous segments (orange). Tumour-suppressor genes in regions with >20% samples attributed to CN17 with LOH segments are labelled. l) Recurrence of mapped CN17 in 1

Mb windows of the human genome in all CN17 attributed BRCA, OV and UCS samples, split by LOH (blue) and heterozygous segments (orange). Tumour-suppressor genes in regions with >20% samples attributed to CN17 with LOH segments are labelled. l) Recurrence of mapped CN17 in 1 Mb windows of the human genome in all CN17 attributed SARC samples, split by LOH (blue) and heterozygous segments (orange). Tumour-suppressor genes in regions with >20% samples attributed to CN17 with LOH segments are labelled. m) Recurrence of mapped CN17 in 1

Mb windows of the human genome in all CN17 attributed SARC samples, split by LOH (blue) and heterozygous segments (orange). Tumour-suppressor genes in regions with >20% samples attributed to CN17 with LOH segments are labelled. m) Recurrence of mapped CN17 in 1 Mb windows of the human genome in all CN17 attributed STAD, LUAD, BLCA, HNSC, ESCA and LUSC samples, split by LOH (blue) and heterozygous segments (orange). Tumour-suppressor genes in regions with >20% samples attributed to CN17 with LOH segments are labelled. n) Association between copy number signature (y-axis) attribution and hypoxia score (x-axis=effect size) in a two-sided multivariate logistic regression model including cancer type as a covariate. Vertical bars indicate effect estimates, horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. P-values for significant associations (P

Mb windows of the human genome in all CN17 attributed STAD, LUAD, BLCA, HNSC, ESCA and LUSC samples, split by LOH (blue) and heterozygous segments (orange). Tumour-suppressor genes in regions with >20% samples attributed to CN17 with LOH segments are labelled. n) Association between copy number signature (y-axis) attribution and hypoxia score (x-axis=effect size) in a two-sided multivariate logistic regression model including cancer type as a covariate. Vertical bars indicate effect estimates, horizontal bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. P-values for significant associations (P <

< 0.05) are given (non-significant values can be found in Supplementary Table 7). n

0.05) are given (non-significant values can be found in Supplementary Table 7). n =

= 6,805 biologically independent tumours.

6,805 biologically independent tumours.

We found an enrichment of CN17 in samples that harbour germline and/or somatic mutations in the key HR genes BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, FBXW7 and CDK12, but not RAD51C (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table 7), and in a more comprehensive analysis of the HR repair pathway (Extended Data Fig. Fig.7c7c and Supplementary Table 7). In addition to mutations, epigenetic silencing of HR genes can result in HRD43. This was further investigated by examining the promoter methylation status of BRCA1 in breast cancers with CN17 attribution. This revealed levels of CN17 comparable to samples with bi-allelic loss of HRD genes (Extended Data Fig. 7d, e). Extending this to a multivariate pan-cancer analysis showed that CN17 was significantly associated with promoter hypermethylation of BRCA1 across cancer types (Extended Data Fig. Fig.7f),7f), in addition to CN9. Further supporting the link between CN17 and HRD, other lines of evidence, including scarHRD scores44 and SBS and ID mutational signatures from WES and WGS, showed a strong correlation with CN17 attribution (Fig. 3e, f, Extended Data Fig. 7g, h and Supplementary Table 7). In addition, positive associations were found between CN17 and the APOBEC mutational signatures SBS2 and SBS13, which are prevalent around DNA double-strand breaks45.

Genome topographical mapping of CN17 in CN17-enriched cancers revealed a distribution of LOH segments (Extended Data Fig. Fig.7i)7i) that was tumour-type-specific, a feature not seen in heterozygous segments (Extended Data Fig. Fig.7j),7j), which suggests that there is tissue-specific-selective forces associated with DNA deletions. Breast cancer, ovarian cancer and uterine carcinosarcoma displayed recurrent chromosomal LOH at 8p, 17 (including BRCA1 and TP53) and 22 (Extended Data Fig. Fig.7k).7k). Focal LOH was also observed on 9q around TSC1, 13q around BRCA2 and RB1, and 19p around STK11. By contrast, CN17-attributed sarcomas displayed strong peaks of recurrent LOH around known sarcoma tumour suppressor genes46 (CDKN2A, RB1 and TP53; Extended Data Fig. Fig.7l).7l). The six other tumour types enriched in CN17 displayed recurrent chromosomal LOH at 8p, 9p, 17p, 19p and 21 (Extended Data Fig. Fig.7m).7m). These findings suggest that copy number signatures could be helpful in revealing the potential mechanisms that underpin the positive selection of cancer genes.

We hypothesized that tumour microenvironmental conditions could provide an explanation for finding CN17 in cancers without mutations in HRD-related genes, as hypoxia can fuel HRD in many cancers47,48. Modelling of copy number signature attributions with comprehensive readouts of transcriptome-based hypoxia gene signatures across cancer types49 revealed a significant positive correlation with CN17 attribution and with signatures of aneuploidy. This result confirms that hypoxia is strongly associated with different patterns of genomic instability, including HRD, in cancer genomes (Extended Data Fig. Fig.7n7n).

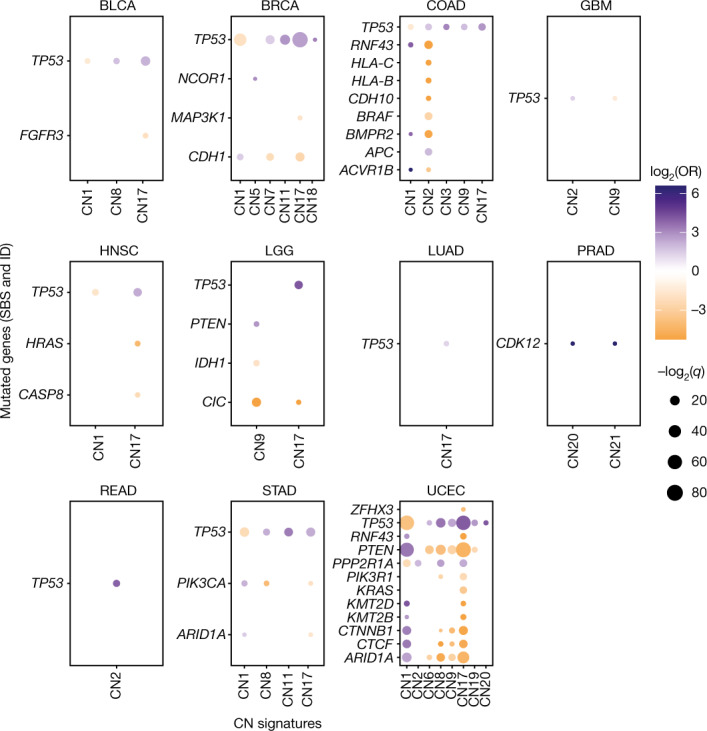

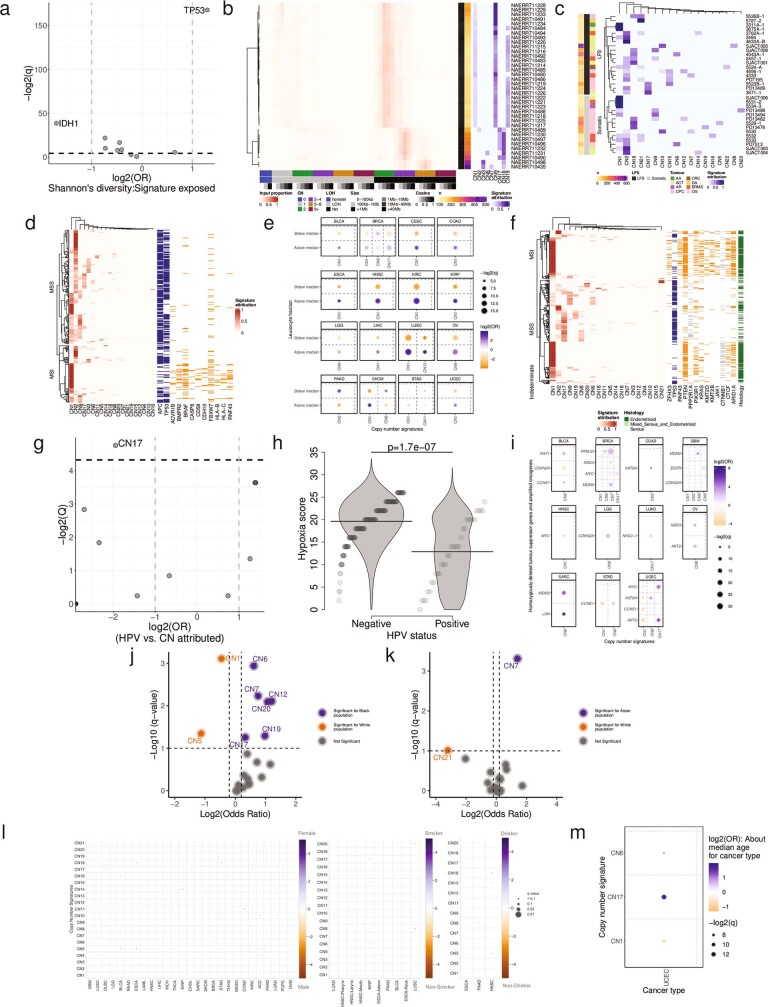

Signatures associated with cancer-driver genes

To identify genetic mechanisms that are potentially causative of copy number signature patterns, we associated somatic cancer-driver gene mutations with copy number signatures and found significant differences between cancer types. A consistent finding across cancer types was a positive association between TP53 mutations and multiple copy number signatures (Fig. (Fig.4a4a and Supplementary Table 8). TP53 mutations were also associated with an increased diversity of copy number signatures (Extended Data Fig. Fig.8a;8a; OR =

= 3.66, q

3.66, q =

= 3.0

3.0 ×

× 10–51), which provides support for a link between TP53 alterations and aneuploidy5. This result was also confirmed through the observation of CIN signatures such as CN9 in SCS data from RPE1 cells in which TP53 mutations were induced and from tumours from patients with Li–Fraumeni syndrome (Extended Data Fig. 8b, c and Supplementary Table 8).

10–51), which provides support for a link between TP53 alterations and aneuploidy5. This result was also confirmed through the observation of CIN signatures such as CN9 in SCS data from RPE1 cells in which TP53 mutations were induced and from tumours from patients with Li–Fraumeni syndrome (Extended Data Fig. 8b, c and Supplementary Table 8).

Associations between copy number signatures (x axis) and driver-gene single nucleotide variant and ID status (y

axis) and driver-gene single nucleotide variant and ID status (y axis) across each TCGA tumour type (panels). Effect size (log2(OR), colour), and significance level (–log2(q), size) from two-sided Fisher’s exact tests are displayed. Non-significant (q

axis) across each TCGA tumour type (panels). Effect size (log2(OR), colour), and significance level (–log2(q), size) from two-sided Fisher’s exact tests are displayed. Non-significant (q ≥

≥ 0.05) associations are not shown.

0.05) associations are not shown.

a) Correlation between Shannon’s diversity index of signature proportions in samples, and driver gene mutation status. Effect size (log2 odds ratio, y-axis) and significance (-log2 Q-value, y-axis) are displayed. Driver genes with |log2(OR)|>1 and Q <

< 0.05 are labelled. TP53 association: OR

0.05 are labelled. TP53 association: OR =

= 3.65, Q

3.65, Q =

= 3.0e- 51. b) Pan-cancer copy number signature attribution in 36 TP53 mutant RPE1 single cell sequenced cells (Mardin et al., 2020). Left: input profile summaries (red). Right: copy number signature attribution (blue). c) Heatmaps of copy number signatures identified across the spectrum of Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS) associated cancers and somatic TP53 mutant cancers. Colour indicates the strength of signature attribution. Somatic=somatic TP53 mutant cancers, LFS=germline TP53 mutant cancers. d) Heatmap of copy number signature attribution (left) and driver gene mutation status (right) for all COAD samples, split by microsatellite instability status. Driver gene mutations are coloured orange or blue for genes that are positively (OR

3.0e- 51. b) Pan-cancer copy number signature attribution in 36 TP53 mutant RPE1 single cell sequenced cells (Mardin et al., 2020). Left: input profile summaries (red). Right: copy number signature attribution (blue). c) Heatmaps of copy number signatures identified across the spectrum of Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS) associated cancers and somatic TP53 mutant cancers. Colour indicates the strength of signature attribution. Somatic=somatic TP53 mutant cancers, LFS=germline TP53 mutant cancers. d) Heatmap of copy number signature attribution (left) and driver gene mutation status (right) for all COAD samples, split by microsatellite instability status. Driver gene mutations are coloured orange or blue for genes that are positively (OR >

> 1, Q

1, Q <

< 0.05) or negatively (OR

0.05) or negatively (OR <

< 1, Q

1, Q <

< 0.05) associated with MSI status respectively, and grey for genes that are not associated with MSI status (q≥0.05). Association between CN1 or CN2 and MSI status: OR

0.05) associated with MSI status respectively, and grey for genes that are not associated with MSI status (q≥0.05). Association between CN1 or CN2 and MSI status: OR =

= 1.8 and 0.21, P

1.8 and 0.21, P =

= 0.03 and 7.7e-9 respectively, Fisher’s exact test. e) Correlations between leukocyte fraction (y-axis, split by median value per tumour type) and copy number signature attribution (x-axis). Effect size given as log2(OR) (colour) and significance given as Q-values (size) are displayed. Only associations with |log2(OR)|>1 and Q

0.03 and 7.7e-9 respectively, Fisher’s exact test. e) Correlations between leukocyte fraction (y-axis, split by median value per tumour type) and copy number signature attribution (x-axis). Effect size given as log2(OR) (colour) and significance given as Q-values (size) are displayed. Only associations with |log2(OR)|>1 and Q <

< 0.05 are shown. Associations were tested with a logistic regression model with leukocyte fraction as the dependent variable and tumour purity and copy number signature attribution (binarized) as independent variables (purity associations not shown). f) Heatmap of copy number signature attribution (left) and driver gene mutation status (right) for all UCEC samples, split by microsatellite instability status. Driver gene mutations are coloured orange or blue for genes that are positively (OR

0.05 are shown. Associations were tested with a logistic regression model with leukocyte fraction as the dependent variable and tumour purity and copy number signature attribution (binarized) as independent variables (purity associations not shown). f) Heatmap of copy number signature attribution (left) and driver gene mutation status (right) for all UCEC samples, split by microsatellite instability status. Driver gene mutations are coloured orange or blue for genes that are positively (OR >

> 1, Q

1, Q <

< 0.05) or negatively (OR

0.05) or negatively (OR <

< 1, Q

1, Q <

< 0.05) associated with MSI status respectively, and grey for genes that are not associated with MSI status (q≥0.05). Association between CN1 or CN2 and MSI status: OR

0.05) associated with MSI status respectively, and grey for genes that are not associated with MSI status (q≥0.05). Association between CN1 or CN2 and MSI status: OR =

= 0.17 and 2.6, P

0.17 and 2.6, P =

= 1.1e-10 and 7.0e-4 respectively, Fisher’s exact test. g) Association between HPV status and copy number signature attribution. X-axis=effect size (log odds ratio), y-axis=significance (-log2 Q-value). Fisher’s exact test. A half dot indicates an infinite value. h) Association between hypoxia score (y-axis) and HPV status (x-axis). Two-sided Mann-Whitney test. n

1.1e-10 and 7.0e-4 respectively, Fisher’s exact test. g) Association between HPV status and copy number signature attribution. X-axis=effect size (log odds ratio), y-axis=significance (-log2 Q-value). Fisher’s exact test. A half dot indicates an infinite value. h) Association between hypoxia score (y-axis) and HPV status (x-axis). Two-sided Mann-Whitney test. n =

= 259 biologically independent tumour samples. i) Associations between copy number signatures (x-axis) and driver gene copy number alteration status (y-axis, amplification for oncogenes, homozygous deletion for tumour-suppressor genes) across each TCGA tumour type (panels). Effect size (log2 odds ratio, colour), and significance level (-log2 Q-value, size) from a Fisher’s exact test are displayed. j) Associations between copy number signatures and TCGA Asian ethnicity, using TCGA White ethnicity as a reference. k) Associations between copy number signatures and TCGA Black ethnicity, using TCGA White ethnicity as a reference. l) Correlation between copy number signature (x-axis) attribution and sex (left), smoking status (middle) and drinking status (right) across TCGA samples. Strength of correlation is indicated by colour (orange=anti-correlated, blue=correlated), Q-value is indicated by size of point. m) Association between copy number signatures (y-axis) and median dichotomised age at diagnosis for individual cancer types (x-axis). Strength of correlation is indicated by colour (orange=negatively associated, blue=positively associated), Q-value is indicated by size of point. Only tumour types/copy number signature combinations with a significant (Q

259 biologically independent tumour samples. i) Associations between copy number signatures (x-axis) and driver gene copy number alteration status (y-axis, amplification for oncogenes, homozygous deletion for tumour-suppressor genes) across each TCGA tumour type (panels). Effect size (log2 odds ratio, colour), and significance level (-log2 Q-value, size) from a Fisher’s exact test are displayed. j) Associations between copy number signatures and TCGA Asian ethnicity, using TCGA White ethnicity as a reference. k) Associations between copy number signatures and TCGA Black ethnicity, using TCGA White ethnicity as a reference. l) Correlation between copy number signature (x-axis) attribution and sex (left), smoking status (middle) and drinking status (right) across TCGA samples. Strength of correlation is indicated by colour (orange=anti-correlated, blue=correlated), Q-value is indicated by size of point. m) Association between copy number signatures (y-axis) and median dichotomised age at diagnosis for individual cancer types (x-axis). Strength of correlation is indicated by colour (orange=negatively associated, blue=positively associated), Q-value is indicated by size of point. Only tumour types/copy number signature combinations with a significant (Q <

< 0.05) association with age at diagnosis are shown.

0.05) association with age at diagnosis are shown.

Mutations in RNF43, HLA-B, HLA-C and BRAF are commonly seen in microsatellite instable colon cancers and were negatively correlated with samples with tetraploid genomes (that is, CN2 attributed; Extended Data Fig. Fig.8d).8d). Microsatellite instability is associated with high immune cell infiltration, whereas aneuploidy is associated with a decrease in leukocyte fraction50. Across multiple cancer types, we observed a general trend of decreased leukocyte fractions in cancers with copy number signatures of aneuploidy compared to diploid cancers while accounting for purity (CN1; Extended Data Fig. Fig.8e).8e). Similar to colon cancer, multiple cancer-driver genes were associated with CN1 and CN2 in endometrial cancer, which was largely driven by differential copy number and mutation patterns seen in microsatellite stable and unstable tumours (Extended Data Fig. Fig.8f).8f). Last, we noted a positive association between CN17 and TP53 mutations in human papilloma virus (HPV) head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSC) (Extended Data Fig. Fig.8g8g and Supplementary Table 8). HNSCs are among the most hypoxic of all cancers and are associated with resistance to radiotherapy49,51. We therefore reasoned that the association seen here with HRD may actually be driven by hypoxia. Indeed, there was a significant increase in hypoxia scores in HPV-negative HNSC (Extended Data Fig. Fig.8h8h).

To assess the relationships between copy number signatures and copy number driver genes, we evaluated the associations between attributions of copy number signatures and either homozygous deletions of tumour suppressor genes or amplifications of known proto-oncogenes (Methods). Copy number drivers such as MDM2, EGFR, CCNE1, MYC and ERBB2 were strongly positively associated with the amplicon signatures CN6–CN8 as well as CN17 (Extended Data Fig. Fig.8i8i and Supplementary Table 8). By contrast, CDKN2A was the only homozygously deleted tumour suppressor gene associated with any signature, most commonly CN9.

We also explored the recent links between ancestry and HRD, genomic instability and chromothripsis52. The copy number signatures CN17 (HRD), CN6 and CN7 (chromothripsis) and some signatures with unknown aetiology were enriched in tumours of individuals with African ancestry (Extended Data Fig. Fig.8j8j and Supplementary Table 8). We further associated tumour copy number signatures in people with Asian ancestry and found an enrichment of CN7 (Extended Data Fig. Fig.8k8k and Supplementary Table 8), a chromothripsis pattern most frequently seen in breast cancers. In contrast to SBS and ID signatures10, no associations were found between any copy number signature and cancer risk factors such as sex, smoking status or alcohol consumption (Extended Data Fig. Fig.8l8l and Supplementary Table 8). Significant associations were found between age and copy number signature attribution in endometrial cancer (Extended Data Fig. Fig.8m8m and Supplementary Table 8); however, this was driven by subtype differences. That is, serous cancer versus endometrioid endometrial cancer (difference in mean age at diagnosis =

= 4.7

4.7 years, P

years, P =

= 8.99

8.99 ×

× 10–5, two-sided Mann–Whitney test), in which non-endometrioid endometrial cancers are strongly associated with HRD53 and enriched in CN17 (OR

10–5, two-sided Mann–Whitney test), in which non-endometrioid endometrial cancers are strongly associated with HRD53 and enriched in CN17 (OR =

= 13.6, P

13.6, P =

= 2.5

2.5 ×

× 10–22, two-sided Fisher’s exact test).

10–22, two-sided Fisher’s exact test).

Discussion

Here we presented a copy number signature framework that provides great utility for the exploration of copy number patterns across multiple cancer types and distinct experimental platforms and exceeds the capabilities provided by mutational signatures of substitutions, IDs or rearrangements. Signatures of substitutions and IDs have translational utility and have been identified across most cancer types and can be generally derived from WGS and, at much lower resolution, WES data54. Rearrangement signatures can only be derived exclusively from WGS data and cannot capture important prognostic information such as WGD. By contrast, this copy number signature framework can be applied across all cancer types, which enabled robust and consistent identification of copy number signatures from WGS, WES, reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS), SCS and SNP6 microarray data.

The identified copy number signatures hold clinical relevance with prognostic implications for patients in which amplicon signatures are observed (Extended Data Fig. Fig.5a).5a). Moreover, the identification of a copy number signature associated with HRD, although not the first such identification18, suggests that incorporating such signatures within existing bioinformatics tools for predicting HRD could further increase the accuracy of these tests55.

The field of copy number signatures is nascent, with multiple distinct methods previously implemented in distinct tumour types16–20. As the field matures, it will become increasingly clear which models are better suited to addressing specific clinical or biological questions. To resolve these questions, pan-cancer analyses that utilize all of these methods will be important, and we present here the first step towards that goal: a mechanism-agnostic pan-cancer compendium of copy number signatures derived from allele-specific profiles.

Methods

Utilized datasets

Using SNP6 microarray data, copy number profiles were generated for 9,873 cancers and matching germline DNA of 33 different types from TCGA6 using allele-specific copy number analysis of tumours (ASCAT)56 with a segmentation penalty of 70 (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, a set of whole-genome sequences from 512 cancers of the International Cancer Genome Consortium that overlapped with tumour profiles in TCGA were analysed33 to generate WGS-derived copy number profiles (see below). Last, a set of whole-exome sequences from 282 cancers from TCGA was analysed to generate exome-derived copy number profiles (see below).

Copy number profile summarization

Copy number segments were classified into three heterozygosity states: heterozygous segments with copy number of (A >

> 0, B

0, B >

> 0) (numbers reflect the counts for major allele A and minor allele B); segments with LOH with copy number of (A

0) (numbers reflect the counts for major allele A and minor allele B); segments with LOH with copy number of (A >

> 0, B

0, B =

= 0); and segments with homozygous deletions (A

0); and segments with homozygous deletions (A =

= 0, B

0, B =

= 0). Segments were further subclassified into five classes on the basis of the sum of major and minor alleles (TCN; Extended Data Fig. Fig.1e)1e) and were chosen for biological relevance as follows: TCN