Abstract

Objective

To compare the risk of interpersonal violence experienced by pregnant and postpartum individuals with physical disabilities, sensory disabilities, or intellectual or developmental disabilities with those without disabilities, and to examine whether a prepregnancy history of interpersonal violence puts individuals with disabilities, at excess risk of interpersonal violence in the perinatal period.Method

This population-based study included all individuals aged 15-49 years with births in Ontario, Canada, from 2004 to 2019. Individuals with physical (n=147,414), sensory (n=47,459), intellectual or developmental (n=2,557), or multiple disabilities (n=9,598) were compared with 1,594,441 individuals without disabilities. The outcome was any emergency department visit, hospital admission, or death related to physical, sexual, or psychological violence between fertilization and 365 days postpartum. Relative risks (RRs) were adjusted for baseline social and health characteristics. Relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) was estimated from the joint effects of disability and prepregnancy violence history; RERI>0 indicated positive interaction.Results

Individuals with physical (0.8%), sensory (0.7%), intellectual or developmental (5.3%), or multiple disabilities (1.8%) were more likely than those without disabilities (0.5%) to experience perinatal interpersonal violence. The adjusted RR was 1.40 (95% CI 1.31-1.50) in those with physical disabilities, 2.39 (95% CI 1.98-2.88) in those with intellectual or developmental disabilities, and 1.96 (95% CI 1.66-2.30) in those with multiple disabilities. Having both a disability and any violence history produced a positive interaction for perinatal interpersonal violence (adjusted RERI 0.87; 95% CI 0.47-1.29).Conclusion

The perinatal period is a time of relative high risk for interpersonal violence among individuals with pre-existing disabilities, especially those with a history of interpersonal violence.Free full text

Disability and Interpersonal Violence in the Perinatal Period

Abstract

Objective:

To compare the risk of interpersonal violence experienced by pregnant and postpartum individuals with a physical, sensory, or intellectual or developmental disability to those without disabilities, and examine if a pre-pregnancy history of interpersonal violence puts individuals with disabilities at excess risk of interpersonal violence in the perinatal period.

Method:

This population-based study included all 15 to 49-year-olds with a birth in Ontario, Canada from 2004–2019. Individuals with physical (N=147 414), sensory (N=47 459), intellectual or developmental (N=2557), or multiple disabilities (N=9598) were compared to 1 594 441 individuals without disabilities. The outcome was any emergency department visit, hospital admission, or death related to physical, sexual, or psychological violence between fertilization and 365 days postpartum. Relative risks (aRR) were adjusted for baseline social and health characteristics. Relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) was estimated from the joint effects of disability and pre-pregnancy violence history, where RERI > 0 indicated positive interaction.

Results:

Individuals with physical (0.8%), sensory (0.7%), intellectual or developmental (5.3%), and multiple disabilities (1.8%) were more likely than those without disabilities (0.5%) to experience perinatal interpersonal violence. The aRR of was 1.40 (95% CI 1.31–1.50) in those with physical, 2.39 (95% CI 1.98–2.88) in those with intellectual or developmental, and 1.96 (95% CI 1.66–2.30) in those with multiple disabilities. Having both a disability and any violence history produced a positive interaction for perinatal interpersonal violence (aRERI 0.87; 95% CI 0.47–1.29).

Conclusion:

The perinatal period is a time of relative high risk for interpersonal violence among individuals with a pre-existing disability, especially those with a history of violence.

PRECIS

The perinatal period is a time of high risk for interpersonal violence among individuals with a pre-existing disability, especially those with a history of violence.

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization defines interpersonal violence as the intentional use of physical force or power against an individual by an intimate partner, family member, or other community member.1 Interpersonal violence against women is a major public health and human rights issue, with one in three individuals experiencing physical, sexual, or psychological abuse in their lifetime, most often perpetrated by an intimate partner.2 Pregnancy is a time of high risk for interpersonal violence, particularly by an intimate partner: more than 30% of intimate partner violence begins in pregnancy,3 and pre-existing violence tends to escalate perinatally.4 Perinatal interpersonal violence has serious negative consequences for pregnant and postpartum people, including elevated risk of mortality5—and neonatal consequences, including elevated risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality.6 Given the perinatal period is a time of increased engagement with medical resources, this period also represents a substantial opportunity for intervention. Such efforts require identification of high-risk groups and development of appropriate resources.

Women with disabilities experience elevated risk of interpersonal violence, with rates of abuse—overall and by an intimate partner—two to four times rates reported by those without disabilities.7–10 Pregnancy rates among people with disabilities are increasing, such that 13% of pregnancies are to people with physical, sensory, or intellectual or developmental disabilities.11 However, despite individuals with disabilities being over-represented in cases of interpersonal violence,7–10 and the perinatal period being a time of elevated risk for interpersonal violence for all pregnant and postpartum people,3,4 few quantitative studies have examined disability and interpersonal violence in the perinatal period. Three prior studies suggest pregnant people with disabilities experience elevated risk of intimate partner violence.12–14 Evidence is lacking on postnatal violence, and on how pre-pregnancy history of interpersonal violence affects perinatal risk.

Our objectives were to: (1) compare the risk of interpersonal violence, reported in emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and deaths, among pregnant and postpartum individuals with a physical, sensory, or intellectual or developmental disability to those without disabilities, and (2) examine if a pre-pregnancy history of interpersonal violence puts individuals with disabilities at excess risk of interpersonal violence in the perinatal period, relative to the risk factors of disability or history of interpersonal violence alone.

METHODS

We undertook a population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada, using data from ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences) (Toronto, Ontario), a research institute that collects administrative data from the health care encounters of all Ontario residents for health system evaluation and improvement. Ontario is Canada’s largest province, with 140 000 births per year,15 and has a universal health care system that provides essential care at no direct cost to residents. Datasets with information on outpatient visits, emergency department visits, hospital admissions, socio-demographics, and deaths (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx) were linked using a unique encoded identifier and accessed and analyzed at ICES. ICES data are complete and valid for primary discharge diagnoses, physician billing claims, and socio-demographics.16

ICES is a prescribed entity under Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA). Section 45 of PHIPA authorizes ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management of, evaluation or monitoring of, the allocation of resources to or planning for all or part of the health system. Projects that use data collected by ICES under section 45 of PHIPA, and use no other data, are exempt from research ethics board review. The use of the data in this project is authorized under section 45 and approved by ICES’ Privacy and Legal Office.

The cohort included all 15 to 49-year-olds with a singleton livebirth or stillbirth conceived between April 1, 2004, and March 31, 2019. Livebirths and stillbirths were identified in the MOMBABY dataset, which is derived from Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database. The MOMBABY dataset includes all maternal-newborn records for hospital births, which represent > 98% of all Ontario births.16 Fertilization date was estimated by subtracting gestational age, ascertained in most cases by first trimester ultrasound,17 from the date of birth. Disability predating fertilization was identified using algorithms developed to identify a disability in health administrative data,18,19 as reported previously.20 These algorithms have been shown to identify disabilities associated with functional limitations.21 and with need for accommodations when accessing health care.22 Briefly, a disability was deemed present if a diagnostic code for a physical (i.e., a congenital anomaly, musculoskeletal disorder, neurological disorder, or permanent injury), sensory (i.e., hearing or vision impairment), or intellectual or developmental disability (i.e., autism spectrum disorder, chromosomal anomalies associated with intellectual disability, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, or intellectual disability), or multiple disabilities (i.e., ≥ 2 of the above), was recorded in ≥ 2 physician visits or ≥ 1 emergency department visits or hospitalizations from database inception (~1988–1991) to fertilization. Those without a pre-pregnancy disability in any of these categories were the comparison group.

The primary outcome was any emergency department visit, hospital admission, or death related to physical, sexual, or psychological interpersonal violence in pregnancy and up to 365 days postpartum (Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). 23,24 External cause of injury codes have 85% accuracy compared to clinical records as a reference standard.25,26 These data capture severe manifestations of interpersonal violence, i.e., those resulting in acute care use or death. In additional analyses, we examined interpersonal violence by (a) timing (i.e., arising in pregnancy and, separately, arising postpartum), (b) type (i.e., physical, sexual, or psychological23), and (c) number of violence-related health care encounters, each separated by at least 24 hours.27

Covariates were derived from the literature, and included age, parity, and social and health characteristics indicative of disparities experienced by individuals with disabilities28,29 which are also associated with increased risk of interpersonal violence (Appendix 3, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). 2–4 We measured neighborhood income quintile by linking postal codes with area-level Census income data. Rural residence was ascertained using the Rurality Index of Ontario, which classifies neighborhoods as urban or rural based on proximity to different types of health care.30 Chronic conditions were identified using collapsed ambulatory diagnostic groups for stable and unstable chronic conditions (excluding codes for disability to avoid overlap) from the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG)® System version 10 in the two years before pregnancy,31 where unstable conditions are those that are more likely to have complications and require more ongoing resources such as specialty care. Mental illness (i.e., a mood or anxiety, psychotic, or other mental disorder) and substance use disorder were ascertained by diagnoses recorded in ≥ 2 physician visits or ≥ 1 emergency department visits or hospital admissions in the two years before pregnancy.32 Finally, we measured any (database inception to the index pregnancy) and recent (< 2 years before the index pregnancy) history of interpersonal violence in ≥ 1 emergency department visits or hospital admissions for physical, sexual, or psychological violence.23,24

We calculated frequencies and percentages to describe baseline characteristics by disability status, and derived standardized differences to compare the distribution of covariates across groups, with > 0.10 indicating meaningful imbalance.33 (Unlike p-values, standardized differences are not influenced by sample size and are therefore appropriate for large cohorts.33)

To address the first objective, we used modified Poisson regression,34 with generalized estimating equations to account for clustering of births to the same mother in the study period,35 to calculate relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for any interpersonal violence in pregnancy and up to 365 days after delivery. We compared individuals with a physical, sensory, intellectual or developmental, or multiple disabilities to those without a disability. RRs were adjusted for covariates that are associated with disability status and are risk factors for interpersonal violence:2–4,28,29 age, parity, neighborhood income quintile, rurality, stable and unstable chronic conditions, mental illness, and substance use disorder; pre-pregnancy history of interpersonal violence was added to the multivariable models in a separate step.

To address the second objective, we employed three metrics to determine if a pre-pregnancy history of interpersonal violence is associated with excess risk of interpersonal violence in individuals with disabilities in the perinatal period, relative to having a disability or a history of interpersonal violence in isolation. This assessment of additive interaction has clinical value because it identifies groups at highest risk of the outcome and therefore most likely to benefit from intervention.36 First, we calculated interaction contrasts (IC), which represent the combined effect of disability and pre-pregnancy history of interpersonal violence on the outcome that cannot be explained by summing their individual effects, derived as the difference in risk differences.37 Second, we measured relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI, also called the interaction contrast ratio), which reflects the excess risk due to interaction relative to the risk without exposure, derived as RR11 − RR10 − RR01 + 1.35,38 RERI > 0 means a positive interaction between disability and pre-pregnancy history of interpersonal violence. Third, we calculated the attributable proportion due to interaction (AP), which is the proportion of the outcome due to interaction among those with both exposures, derived as RERI / RR11.35,38

In additional analyses, we estimated (a) modified Poisson regression models to separately examine the risks of interpersonal violence in pregnancy and postpartum; (b) modified Poisson regression models to separately determine the risks of physical, sexual, and psychological violence perinatally; and (c) multinomial logistic regression models to examine the odds of having 1 or ≥ 2 violence-related health care encounters perinatally, relative to zero encounters. All analyses used SAS version 9.4.

RESULTS

During the study period, there were 147 414 births to individuals with a physical disability, 47 459 to those with a sensory disability, 2557 to those with an intellectual or developmental disability, 9598 to those with multiple disabilities, and 1 594 441 to those without disabilities. Compared to those without disabilities, individuals with sensory, intellectual or developmental, and multiple disabilities were younger, and individuals with an intellectual or developmental disability were more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods. Individuals with physical disabilities and multiple disabilities had elevated rates of stable chronic conditions, and all disability groups had elevated rates of unstable chronic conditions. All disability groups had elevated rates of mental illness, and those with intellectual or developmental disabilities and multiple disabilities had elevated rates of substance use disorders. All disability groups were more likely to have a history of interpersonal violence in the two years before the index pregnancy (Table 1) (Appendix 4, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 15- to 49-year-olds with a physical, sensory, intellectual or developmental, or multiple disabilities, and those without a disability, who had a singleton livebirth or stillbirth in Ontario, Canada, 2004–2019. Data presented as number (%).

| Physical disability (N=147 414) | Sensory disability (N=47 459) | Intellectual or developmental disability (N=2557) | Multiple disabilities (N=9598) | No disability (N=1 594 441) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||||

15–24 15–24 | 25 674 (17.4) | 10 651 (22.4) * | 1166 (45.6) * | 2293 (23.9) * | 273 412 (17.1) |

25–34 25–34 | 91 386 (62.0) | 27 832 (58.6) * | 1100 (43.0) * | 5382 (56.1) * | 1 027 201 (64.4) |

35–49 35–49 | 30 354 (20.6) | 8976 (18.9) | 291 (11.4) * | 1923 (20.0) | 293 828 (18.4) |

| Multiparous | 85 851 (58.2) | 25 881 (54.5) | 1,422 (55.6) | 5372 (56.0) | 911 510 (57.2) |

| Neighborhood income quintile (Q) | |||||

Q1 (lowest) Q1 (lowest) | 31 631 (21.5) | 10 447 (22.0) | 975 (38.1) * | 2488 (25.9) | 351 994 (22.1) |

Q2 Q2 | 29 320 (19.9) | 9650 (20.3) | 564 (22.1) | 2001 (20.8) | 321 063 (20.1) |

Q3 Q3 | 29 998 (20.3) | 9708 (20.5) | 422 (16.5) * | 1918 (20.0) | 327 666 (20.6) |

Q4 Q4 | 30 992 (21.0) | 9899 (20.9) | 298 (11.7) * | 1760 (18.3) | 328 161 (20.6) |

Q5 (highest) Q5 (highest) | 24 801 (16.8) | 7596 (16.0) | 278 (10.9) * | 1391 (14.5) | 259 394 (16.3) |

Missing Missing | 672 (0.5) | 159 (0.3) | 20 (0.8) | 40 (0.4) | 6163 (0.4) |

| Rural region of residence | 8464 (5.7) | 2115 (4.5) | 145 (5.7) | 553 (5.8) | 66 689 (4.2) |

Missing Missing | 2473 (1.7) | 605 (1.3) | 79 (3.1) * | 155 (1.6) | 22 121 (1.4) |

| Stable chronic conditions | 40 325 (27.4) * | 12 216 (25.7) | 630 (24.6) | 3126 (32.6) * | 365 302 (22.9) |

| Unstable chronic conditions | 24 292 (16.5) * | 7048 (14.9) * | 390 (15.3) * | 2160 (22.5) * | 185 290 (11.6) |

| Mental illness | 28 752 (19.5) * | 8195 (17.3) * | 1056 (41.3) * | 2581 (26.9) * | 200 340 (12.6) |

| Substance use disorder | 2962 (2.0) | 589 (1.2) | 213 (8.3) * | 356 (3.7) * | 14 707 (0.9) |

| Any history of interpersonal violence before pregnancy | 6317 (4.3) | 1734 (3.7) | 340 (13.3) * | 732 (7.6* | 32 990 (2.1) |

| Recent history of interpersonal violence < 2 years before pregnancy | 2347 (1.6) * | 628 (1.3) * | 201 (7.9) * | 317 (3.3) * | 13 025 (0.8) |

Individuals with physical (0.8%), sensory (0.7%), intellectual or developmental (5.3%), and multiple disabilities (1.8%) were more likely than those without disabilities (0.5%) to experience interpersonal violence in the perinatal period (Table 2). After adjusting for covariates, risks were elevated for those with physical (aRR 1.40, 95% CI 1.31–1.50), intellectual or developmental (aRR 2.39, 95% CI 1.98–2.88), and multiple disabilities (aRR 1.96, 95% CI 1.66–2.30), but not those with sensory disabilities (aRR 1.06, 95% CI 0.94–1.19).

Table 2.

Risk of experiencing interpersonal violence in pregnancy and up to 365 days after delivery, in individuals with a disability, compared to those without any recognized disability.

| Disability status | N (%) with outcome | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Model 1: Adjusted RR (95% CI) * | Model 2: Adjusted RR (95% CI) † |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No disability (N=1 594 441) | 7474 (0.5) | [Referent] | [Referent] | [Referent] |

| Physical disability only (N=147 414) | 1183 (0.8) | 1.68 (1.57–1.81) | 1.52 (1.42–1.63) | 1.40 (1.31–1.50) |

| Sensory disability only (N=47 459) | 311 (0.7) | 1.39 (1.22–1.57) | 1.13 (1.00–1.28) | 1.06 (0.94–1.19) |

| Intellectual or developmental disability only (N=2557) | 135 (5.3) | 11.08 (9.10–13.51) | 3.05 (2.53–3.68) | 2.39 (1.98–2.88) |

| Multiple disabilities (N=9598) | 173 (1.8) | 3.84 (3.22–4.59) | 2.38 (2.01–2.81) | 1.96 (1.66–2.30) |

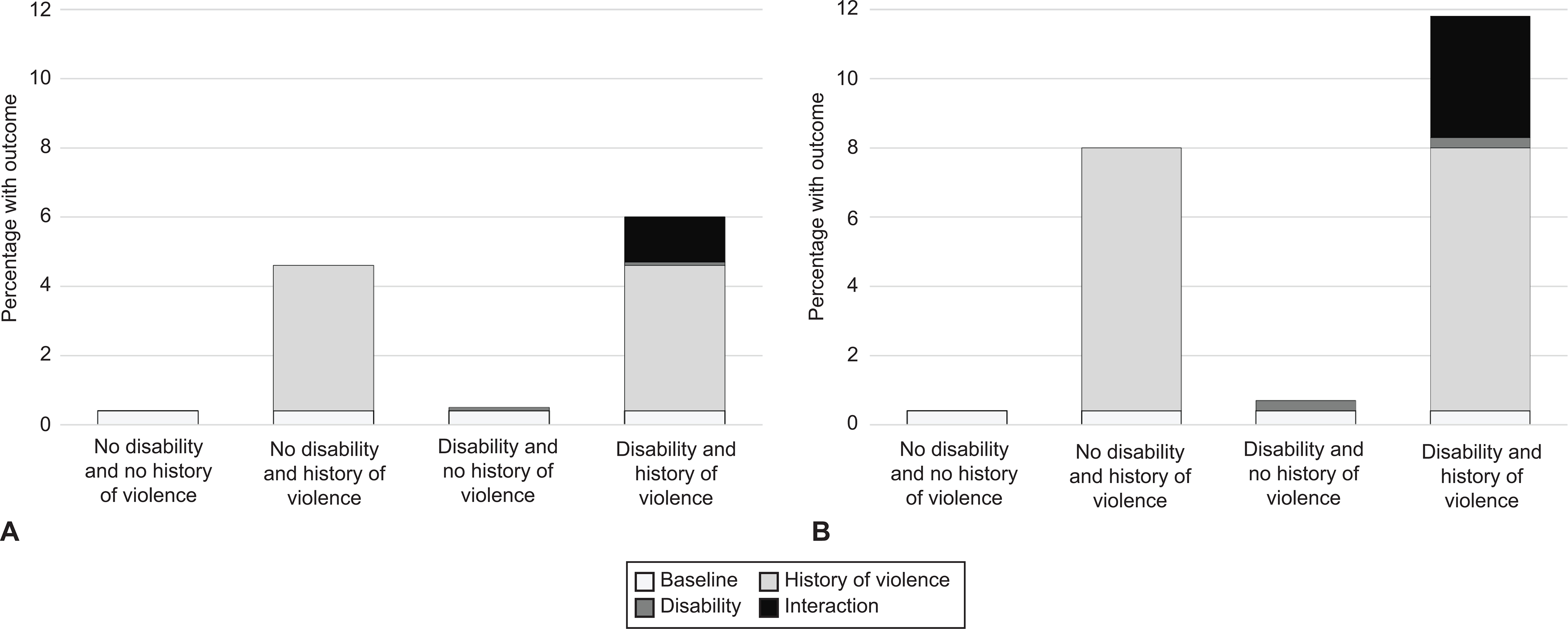

Individuals with disabilities with a history of interpersonal violence predating the index pregnancy had excess risk for interpersonal violence perinatally. For any history of interpersonal violence, the IC indicated an absolute rate of interpersonal violence in the perinatal period of 1.3% (95% CI 1.2%–1.3%) due to the combined effects of disability and pre-pregnancy history of interpersonal violence (aRERI 0.87, 95% CI 0.47–1.29; aAP 18.2%, 95% CI 10.8%–25.5%) (Figure 1a, Table 3). For recent history of interpersonal violence < 2 years before the index pregnancy, the IC indicated an absolute rate of interpersonal violence in the perinatal period of 3.5% (95% CI 3.2%–3.8%) due to the combined effects of disability and pre-pregnancy history of interpersonal violence (aRERI 1.61, 95% CI 0.94–2.34; aAP 26.5%, 95% CI 16.8%–34.8%) (Figure 1b, Table 3).

Additive interaction between disability status and any history of interpersonal violence before pregnancy (A) and a recent history of interpersonal violence in the 2 years before pregnancy (B), on the risk of interpersonal violence in pregnancy and up to 365 days after delivery.

Table 3.

Additive interaction between disability status and any and recent history of interpersonal violence on the risk of interpersonal violence in pregnancy and up to 365 days after delivery.

| Risk factor status | N (%) with outcome | RR (95% CI) | RERI (95% CI) * | AP (95% CI) † | aRR (95% CI) *‡ | aRERI (95% CI) | aAP (95% CI) †‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any history of interpersonal violence before pregnancy | |||||||

| No disability + no history of violence | 5366 (0.4) | [Referent] | 3.31 (2.42–4.25) | 29.1% (23.2%–35.6%) | [Referent] | 0.87 (0.47–1.29) | 18.2% (10.8%–25.5%) |

| No disability + history of violence | 2108 (4.6) | 7.23 (6.55–7.98) | 3.49 (3.24–3.77) | ||||

| Disability + no history of violence | 1043 (0.5) | 1.59 (1.49–1.71) | 1.41 (1.32–1.52) | ||||

| Disability + history of violence | 759 (6.0) | 11.41 (9.76–12.70) | 4.78 (4.31–5.29) | ||||

| Recent history of interpersonal violence (< 2 years before pregnancy) | |||||||

| No disability + no history of violence | 6434 (0.4) | [Referent] | 9.59 (7.07–12.33) | 40.0% (32.7%–47.2%) | [Referent] | 1.61 (0.94–2.34) | 26.5% (16.8%–34.8%) |

| No disability + history of violence | 1040 (8.0) | 13.51 (11.98–15.24) | 4.06 (3.68–4.49) | ||||

| Disability + no history of violence | 1389 (0.7) | 1.59 (1.49–1.71) | 1.40 (1.31–1.51) | ||||

| Disability + history of violence | 413 (11.8) | 23.69 (20.32–27.63) | 6.08 (5.34–6.93) |

Abbreviations: RERI = relative excess risk due to interaction; AP = attributable proportion due to interaction.

Compared to those without a disability, all disability groups experienced elevated risk of interpersonal violence during pregnancy, and those with physical, intellectual or developmental, and multiple disabilities, but not sensory disabilities, experienced elevated risk in the postpartum period (Appendix 5, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). Individuals with physical, intellectual or developmental, and multiple disabilities, but not sensory disabilities, experienced elevated risks of physical violence. All disability groups had a higher associated risk of sexual violence, and those with physical or multiple disabilities, but not intellectual or developmental or sensory disabilities, had a higher risk of psychological violence (Appendix 6, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). Individuals with physical, intellectual or developmental, and multiple disabilities, but not sensory disabilities, experienced the highest odds of having ≥ 2 health care encounters for violence perinatally (Appendix 7, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx).

DISCUSSION

In this population-based study, interpersonal violence resulting in an emergency department visit, hospitalization, or violent death in the perinatal period occurred more often in individuals with disabilities. Risks for those with intellectual or developmental and multiple disabilities were particularly high, with unadjusted rates 11 and nearly four times, respectively, that of individuals without disabilities. A history of interpersonal violence was associated with excess risk of perinatal interpersonal violence among those with disabilities. These data have implications for perinatal violence prevention, demonstrating the importance of appropriate screening tools, accessible violence-related information and services, and health care professional education to meet the needs of individuals with disabilities.

Few quantitative studies have examined perinatal interpersonal violence in people with disabilities.10 All existing studies were conducted in the United States and used self-reported data on physical violence in pregnancy by an intimate partner from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System.12–14 These studies reported adjusted odds ratios ranging from 1.5013 to 2.812 comparing pregnant people with versus without disabilities. None adjusted for pre-pregnancy abuse, which may explain the stronger effects compared to ours. Our study adds to the literature by documenting risks of severe presentations of interpersonal violence resulting in emergency department visits, hospitalizations, or death. Our data span the full perinatal period and examine different disability groups separately. We also illustrate the synergistic effects of disability and pre-pregnancy history of violence on the risks of interpersonal violence perinatally.

There are several reasons individuals with disabilities may be at greater risk than those without disabilities for interpersonal violence perinatally. For numerous social and structural reasons,28 people with disabilities have high rates of many risk factors for interpersonal violence, including low socioeconomic status and mental illness.39 Risks were reduced after controlling for these factors. Research outside the perinatal period suggests elevated interpersonal violence rates also reflect disability-related and economic needs that increase reliance on others, including intimate partners, for support; social stereotypes of disability that reduce personal agency and perceived credibility; communication difficulties; and lack of accessible information and services that promote violence awareness and prevention.7–10 For those with intellectual or developmental disabilities, other contributors include lack of awareness about violence, rights, and services.7–10 The strongest risk factor for perinatal interpersonal violence is a pre-pregnancy history of violence.39 Our findings supported the hypothesis that disability and pre-pregnancy history of interpersonal violence have synergistic effects, with excess risk for interpersonal violence perinatally in individuals with disabilities with a history of violence. The perinatal period may be a time of extra vulnerability for these individuals due to greater reliance on others for economic and disability-related needs40 and fears that reporting violence may trigger a report to child protective services.41

Several limitations should be considered. Only singleton pregnancies resulting in a livebirth or stillbirth were included; thus, our findings may not be generalizable to individuals with twins or higher order multiples, or to pregnancies ending in a miscarriage or induced abortion. Disability ascertainment was restricted to medical records, meaning that undiagnosed disabilities were missed.19 This might bias estimates toward the null. We were only able to detect violence in acute care and death records;23,24 under-estimation may have been greater in people with disabilities than those without disabilities given people with disabilities are less likely to disclose violence,42 and health care professionals are less likely to ask them about violence.42 Because individuals experiencing sexual and psychological violence are less likely to seek care, these types of violence are especially likely to be underestimated in administrative data. We also had no reliable information on perpetrators (e.g., intimate partners) since such data are not mandatory in administrative data.24 Sexual violence (e.g., sexual coercion, rape) may result in pregnancy as well as ongoing violence in pregnancy, but we were unable to assess this in our study. Finally, we were missing data on relationship status and living situation.

Our findings have critical implications given that interpersonal violence in pregnancy and postpartum acts as a barrier to care41 and a risk factor for adverse perinatal outcomes.5,6 Tools used for violence screening perinatally43 do not include items about forms of violence that are unique to individuals with disabilities, such as refusal to assist with activities of daily living. People with disabilities also face a “fear of double disclosure,”41 worrying not only about stigma surrounding interpersonal violence, but also about how health care professionals’ negative attitudes toward disability might impact care.41 Further, violence-related information and services are frequently inaccessible. Our findings underscore the importance of screening tools that address forms of violence often experienced by people with disabilities,44,45 health care professional training and awareness, and resources that address physical and communication-related accessibility needs.41,42 Finally, given the strongest risk factor for interpersonal violence in the perinatal period, particularly in those with a disability, was a pre-pregnancy history of interpersonal violence, our findings suggest more could be done before pregnancy to offer screening and support at the index encounter, thereby reducing risks of perinatal violence.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content_1

Supplemental Digital Content_2

Acknowledgments:

Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed in the material are those of the author(s), and not necessarily those of CIHI. Parts of this report are based on Ontario Registrar General (ORG) information on deaths, the original source of which is ServiceOntario. The views expressed therein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of ORG or the Ministry of Government Services. Geographical data are adapted from Statistics Canada, Postal Code Conversation File + 2011 (Version 6D) and 2016 (Version 7B). This does not constitute endorsement by Statistics Canada of this project.

Funding:

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award # 5R01HD092326. This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program to Dr. Hilary K. Brown. The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Natasha Saunders receives an honorarium from the BMJ Group (Archives of Diseases in Childhood). Simone N. Vigod receives royalties from UpToDate for authorship of materials related to depression and pregnancy.

Presented at the Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research Annual Meeting on June 1, 2022.

REFERENCES

Citations & impact

This article has not been cited yet.

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/136893948

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Association of Preexisting Disability With Severe Maternal Morbidity or Mortality in Ontario, Canada.

JAMA Netw Open, 4(2):e2034993, 01 Feb 2021

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 33555330 | PMCID: PMC7871190

A population-based analysis of postpartum acute care use among women with disabilities.

Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM, 4(3):100607, 03 Mar 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35248782 | PMCID: PMC9703340

Perinatal mental illness among women with disabilities: a population-based cohort study.

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 57(11):2217-2228, 08 Aug 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 35939075 | PMCID: PMC9722243

Safeguarding strategies in athletes with intellectual disabilities: A narrative review.

PM R, 16(4):374-383, 05 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38009695

Review