Abstract

Free full text

A randomized trial of safety, acceptability and adherence of three rectal microbicide placebo formulations among young sexual and gender minorities who engage in receptive anal intercourse (MTN-035)

Abstract

Efforts to develop a range of HIV prevention products that can serve as behaviorally congruent viable alternatives to consistent condom use and oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) remain crucial. MTN-035 was a randomized crossover trial seeking to evaluate the safety, acceptability, and adherence to three placebo modalities (insert, suppository, enema) prior to receptive anal intercourse (RAI). If participants had no RAI in a week, they were asked to use their assigned product without sex. We hypothesized that the modalities would be acceptable and safe for use prior to RAI, and that participants would report high adherence given their behavioral congruence with cleansing practices (e.g., douches and/or enemas) and their existing use to deliver medications (e.g., suppositories; fast-dissolving inserts) via the rectum. Participants (N = 217) were sexual and gender minorities enrolled in five different countries (Malawi, Peru, South Africa, Thailand, and the United States of America). Mean age was 24.9 years (range 18–35 years). 204 adverse events were reported by 98 participants (45.2%); 37 (18.1%) were deemed related to the study products. The proportion of participants reporting “high acceptability” was 72% (95%CI: 65% - 78%) for inserts, 66% (95%CI: 59% - 73%) for suppositories, and 73% (95%CI: 66% - 79%) for enemas. The proportion of participants reporting fully adherent per protocol (i.e., at least one use per week) was 75% (95%CI: 69% - 81%) for inserts, 74% (95%CI: 68% - 80%) for suppositories, and 83% (95%CI: 77% - 88%) for enemas. Participants fully adherent per RAI-act was similar among the three products: insert (n = 99; 58.9%), suppository (n = 101; 58.0%) and enema (n = 107; 58.8%). The efficacy and effectiveness of emerging HIV prevention drug depends on safe and acceptable delivery modalities that are easy to use consistently. Our findings demonstrate the safety and acceptability of, and adherence to, enemas, inserts, and suppositories as potential modalities through which to deliver a rectal microbicide.

Introduction

The HIV epidemic has affected people across the globe over the past four decades, with sexual and gender minorities (SGM; i.e., populations with same-sex or same-gender attractions or behaviors and who may identify with a non-heterosexual identity such as gay, bisexual, queer, etc.)carrying much of the burden of new diagnoses [1]. While HIV prevalence rates vary among SGM in different regions (4% sub-Saharan Africa, 32% South East Asia, 44% South America, and 55% North America), the risk of acquiring HIV is 28 times higher among men who have sex with men (MSM) than adult men and 14 times higher for transgender people when compared to adult women [1]. Innovative biomedical advancements across the HIV prevention continuum (e.g., HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis [PrEP]) have offered new opportunities to curtail HIV incidence [2], yet new HIV infections have remained high globally due to acceptability, access, uptake, and adherence challenges to these highly effective biomedical prevention tools [3]. Optimal uptake and adherence to PrEP has been hindered further by financial barriers and social stigma [4, 5], challenges accessing inclusive and sustained HIV prevention services [3, 6–8], or concerns regarding the possible side effects of systemic delivery of PrEP [9]. Therefore, efforts to develop a range of HIV prevention products that can serve as viable alternatives and/or complements to consistent condom use and oral PrEP, including formulations able to deliver multiple drugs (e.g., anti-HIV-1 and anti-HSV-2) in combination, remain crucial.

Researchers and advocates have proposed expanding modalities of PrEP delivery, including the use of rectal microbicides (RMs); topical biomedical products being developed to reduce the risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for use with sexual activity [9–11]. If found to be safe and effective, RMs may offer an episodic prevention modality for individuals who would perceive a pericoital prevention strategy more feasible and preferable to systemic daily or on demand oral PrEP modalities [9, 12]. In a randomized, cross-over trial comparing daily oral PrEP to two regimens (daily use and event-driven) of a rectal microbicide gel candidate, MSM and transgender women varied in their preferred strategy after using the products [13], with nearly 30% of the sample rating daily oral PrEP as the least preferred prevention method. Twenty percent of participants preferred an event-driven rectal microbicide strategy when engaging in condomless anal sex. Therefore, it is crucial for RMs to be designed so that they can be delivered via mechanisms that not only deliver enough drug to block HIV/STI transmission but are also a good behavioral fit with the intended end-users based on their lifestyles.

Most rectal microbicide candidates have been formulated as gels because of their similarities to lubricants, highlighting the potential for the rectal microbicide gel to be readily incorporated into users’ sexual practices [10, 14–16]. While ideal from a behavioral congruence perspective, these gel formulations have required the use of an applicator to achieve sufficient drug delivery, which could present acceptability and adherence challenges for long-term uses [17, 18], At this time, it is unclear if topical gels would be able to deliver protective levels of HIV prevention drugs when used without an applicator [15, 19, 20]. As such, researchers and advocates have argued that other rectal delivery modalities should be considered, including suppositories, fast-dissolving inserts, and enemas [21–23].

Survey research with SGM populations across various countries has found high hypothetical acceptability to a rectal microbicide formulated as a suppository, insert, or enema [21, 24, 25]. while promising, the hypothetical nature of these studies limits our ability to understand whether SGM populations would find these modalities acceptable after using them with their partners prior to receptive anal intercourse (rai), and whether they would consistently use them when engaging in rai. to date, few studies with SGM populations have examined the acceptability, uptake of, and adherence to inserts, suppositories, or enemas as a rectal microbicide modality to be used prior to sex [26]. in a randomized, crossover acceptability trial where HIV-negative MSM used both 35 ml of placebo gel and an 8g placebo suppository prior to three rai occasions, respectively, participants noted moderate acceptability for the suppository, with the greatest proportion of participants preferring the gel over the suppository [26]. two clinical trials are examining the acceptability of rectal microbicide candidates as a fast-dissolving insert (mtn 039; nct04047420) and an enema (dream; nct04016233) for use among SGM populations, yet the results of these trials have yet to be released. moreover, no study has examined these modalities within the same trial, limiting our ability to compare their acceptability, safety, and adherence among SGM individuals who have used all three products rectally prior to rai. therefore, with the goal of supporting the development of behaviorally congruent rectal microbicide modalities for topical PrEP delivery, the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN) developed MTN-035 (DESIRE; Developing and Evaluating Short-Acting Innovations for Rectal Use) to identify acceptable modalities among SGM in five different countries: Malawi, Peru, South Africa, Thailand, and the United States of America.

The primary objectives of MTN-035 were to evaluate the acceptability and safety of and adherence to three placebo modalities–an insert, a suppository, and an enema–that could be used prior to RAI in a randomized, cross-over trial. We hypothesized that all three modalities would be acceptable and safe for use prior to RAI, and that SGM participants would report high adherence to these modalities given their behavioral congruence with cleansing practices (e.g., enemas) and their familiar use to deliver medications (e.g., suppositories; fast-dissolving inserts) via the rectum.

Materials and methods

Sample

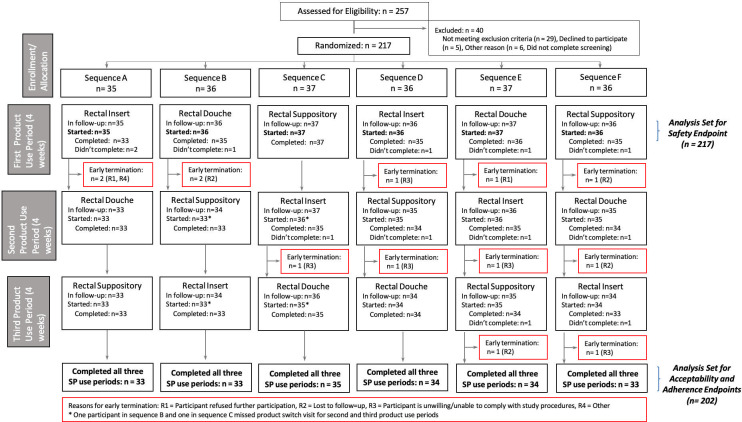

HIV-uninfected transgender men, transgender women, and cisgender MSM between the ages of 18 and 35 were recruited into the trial (see Fig 1). Data collection took place between April 2019 and July 2020 in the United States (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Birmingham, Alabama; and San Francisco, California), Thailand (Chiang Mai), Peru (Lima), Malawi (Blantyre), and South Africa (Johannesburg).

Participants were recruited from a variety of sources, including outpatient clinics, universities, community-based locations, online websites, and social networking applications. In addition, participants were also referred to the study from other local research projects, research registries and other health and social service providers. At some sites, prospective participants were pre-screened by phone, using an IRB-approved phone script, to assess presumptive eligibility based on select behavioral and medical eligibility requirements. This includes a review of the prospective participants’ sexual history and engagement in receptive anal sex in their lifetime and within the previous three months. For those deemed presumably eligible when a phone screen was conducted, a screening visit was scheduled. A re- affirmation of all eligibility criteria was obtained and confirmed during a formal screening and enrollment visit, described below.

The study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards (IRB)/Ethics Committees at all participating institutions, including the Health Research Ethics Council, South African Health Products Regulatory Authority, the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health IRB, the Research Institute for Health Sciences Human Experimentation Committee, the Medical Device Control Division/Thai Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the IMPACTA Bioethics Committee, the Peruvian National Institute of Health (Instituto Nacional de Salud), the Peruvian FDA, the Peruvian Ministry of Health, the University of Pittsburgh IRB, the University of California San Francisco IRB, University of Alabama at Birmingham IRB, and the University of Pennsylvania IRB. This study was submitted to clincialtrials.gov on September 14, 2018, assigned number NCT03671239.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included: 1) men (cis or transgender) and transgender women between 18–35 years old; 2) ability and willingness to provide written informed consent in local language; 3) HIV- 1/2 uninfected at Screening and Enrollment; 4) ability and willingness to provide adequate contact and location information; 5) availability to return for all study visits and willingness to comply with study participation requirements; 6) deemed to be in general good health by a healthcare provider at Screening and Enrollment; 7) a reported history of consensual RAI at least three times in the past three months and expectation to maintain at least that frequency of RAI during study participation; 8) willingness to not take part in other research studies involving drugs, medical devices, genital or rectal products, or vaccines for the duration of study participation; 9) For individuals who could get pregnant (transgender men with a female reproductive system), a negative pregnancy test at Screening and Enrollment; 10) For individuals who could get pregnant, use of an effective method of contraception for at least 30 days (inclusive) prior to Enrollment, and intention to use an effective method for the duration of study participation. Exclusion criteria included history of inflammatory bowel disease or anorectal condition impeding product placement or assessment of tolerability; anticipated use of non-study rectally administered products; any prior participation in research studies involving rectal products; having an active anorectal or reproductive tract infection requiring treatment or symptomatic urinary tract infection (these participants could be retested during screening and could enroll if resolved); and pregnancy or breast-feeding.

Screening, enrollment and retention

Participants were screened for eligibility prior to enrolling in the study. All enrolled participants provided written informed consent. Participants returned to the clinic within the 45-day screening window where they completed administrative, behavioral, clinical, and laboratory procedures. Additionally, clinical results or treatments for urinary tract infections, genital/reproductive tract infections, sexually transmitted infections (UTIs/RTIs/STIs) or other findings were provided as clinically indicated at all visits. At all clinic visits, participants were also dispensed condoms and lubricant. Consented and enrolled participants were then randomized into one of six sequences, each varying the order in which participants used the study placebo products, with a 1-week wash-out period between each 4-week product use period (Table 1).

Table 1

| Sequence | Period 1 (4 weeks) | Washout period (~1 week) | Period 2 (4 weeks) | Washout period (~1 week) | Period 3 (4 weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Rectal Insert | Rectal Enema | Rectal Suppository | ||

| B | Rectal Enema | Rectal Suppository | Rectal Insert | ||

| C | Rectal Suppository | Rectal Insert | Rectal Enema | ||

| D | Rectal Insert | Rectal Suppository | Rectal Enema | ||

| E | Rectal Enema | Rectal Insert | Rectal Suppository | ||

| F | Rectal Suppository | Rectal Enema | Rectal Insert |

Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:1:1:1 ratio to one of six study product application sequences (A-F), with the randomization configuration based on permuted blocks, to keep the allocation balanced. The randomization scheme, including enrollment of replacement participants, was generated and maintained by the MTN Statistical Data Manager Center (SCHARP), and it was configured in the Medidata Balance system prior to site activation. This allowed for participants being assigned to a randomized sequence by the system, only after site staff confirmed them as eligible and willing to enroll in the study.

Each participant was followed for approximately 3.5 months and was expected to complete eight visits (including Screening and Enrollment visits). A regular visit was considered missed if the participant did not complete any part of the visit within the visit window. If an interim visit was completed to make up for the missed regular visit, then the missed regular visit was calculated as completed.

Study procedures

Each participant received placebo inserts, placebo suppositories, and placebo (water) enema bottles for pericoital rectal administration (see Fig 2). The rectal suppository is approximately 3–3.8 cm (1.2–1.5 inches) long and 2 grams in weight. The placebo rectal suppository consists of a Witepsol® H5 (IOI Oleochemical) base and contains 15% diglyceride and not more than 1% monoglyceride content. The placebo rectal insert provided by CONRAD is formulated into white to off-white uncoated solid dosage forms in a bullet shape. The insert contains the following inactive excipients: isomalt, xylitol, sodium CMC, povidone, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, poloxamer 188, sodium stearyl fumarate and magnesium stearate. The insert is 1.5 cm (0.6 inches) long, 0.7 cm (0.28 inches) wide, 0.6 cm (0.23 inches) in height, and approximately 500 mg in weight.

The products were administered in order of the assigned sequence and prior to each respective product use period. Participants were instructed to use one dose of the assigned study product between 30 minutes and 3 hours prior to RAI, following their usual pre-RAI practices, and not to use more than one product dose in 24 hours. If a participant did not engage in RAI in a given week, they were asked to insert a dose of the product in the absence of RAI. Participants self-administered the first dose of each product in the clinic to ensure correct administration.

The schedule of participants’ study activities is depicted in Fig 3. At Visit 2, participants were provided with their first rectal product for period 1, based on their assigned sequence. For Visits 3, 5, and 7, participants returned to the clinic for the product use end visits. At these visits, participants completed study procedures, including pharyngeal, urine, blood, pelvic (individuals with a vagina or neovagina), and anorectal tests, if indicated (required at Visit 7). Participants completed a baseline computer assisted self-interview (CASI) during their enrollment visit (Visit 2) and at the end of each product use end visit (Visits 3, 5, and 7).

After an approximately 7-day washout period following study product use periods, participants returned to the clinic to complete Visits 4 and 6. At these visits, participants completed study procedures, including pharyngeal, urine, blood, pelvic (individuals with a vagina or neovagina), and anorectal tests, if indicated. Additionally, participants self-administered one dose of the product they were dispensed and collected the remaining product in their sequence to use for the next four weeks during periods 2 and 3; they were also given product use instructions.

Visit 8 served as the follow-up safety contact and termination visit where participants completed study procedures as well as received clinical results or treatment for UTIs/RTIs/STIs or other findings. Participant reimbursement was based on local guidelines and approved by the local IRBs/ECs prior to study implementation.

We undertook several efforts to minimize the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic during our data collection period, including revising when and how products were dispensed during periods of COVID-19 restrictions. Of the 78 enrolled participants when the COVID-19 pandemic began, only four did not receive all three products (see Jacobson et al. [27] for details).

Primary safety endpoint

Our primary safety endpoint was defined as the presence of a Grade 2 or higher related adverse events (AEs) as defined by the Division of AIDS Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Pediatric Adverse Events, Corrected Version 2.1, July 2017 and Addenda 1, 2 and 3 (Female Genital [Dated November 2007], Male Genital [Dated November 2007] and Rectal [Clarification dated May 2012] Grading Tables for Use in Microbicide Studies [28–31].

Primary acceptability endpoint

Acceptability endpoints were based on participants’ responses to the CASI for each product at their respective product use end visits (Visits 3, 5 and 7). Using a 10-point scale (1 = Very Unlikely; 10 = Very Likely), participants were asked to answer the following question about their most recently used product: “Think about the positive and negative experiences you have had using the [study product] during the past 4-week period. If this [study product] was available and it provided some protection against HIV, how likely would you be to use it before receptive anal sex?”. The endpoint was operationalized as binary, with scores 1 to 6 grouped as “low acceptability” and scores 7 to 10 as “high acceptability”.

Primary adherence endpoints

Adherence to use of each assigned product, as per-protocol, was based on the number of weeks that a participant missed using an assigned product (0 to 4 weeks), using a given product use end visit CASI assessment: “The following questions refer to your use of the study provided rectal [study product: enema, insert or suppository] over the past 4 weeks. You were asked to insert the study provided rectal [study product] in your rectum at least once a week during the past 4 weeks. However, for different reasons, people might have encountered difficulties using the [study product]. Thinking about your experience during these past four weeks, in how many of the weeks did you miss a rectal [study product] application?”. The adherence per-protocol was operationalized as binary, with participants who reported not having missed any application classified as “adherent”.

Additionally, adherence per RAI-act was defined (for participant-periods with at least one RAI act was reported) as the proportion of times that participants reported having used the study-provided enema, insert or suppository before RAI. We determined adherence per RAI act by dividing participants’ responses to their CASI assessments regarding the number of times a participant noted using the study product before RAI by the total number of RAI acts self-reported over the same 4-week period. Participants are classified as fully adherent per RAI-act if they reported using the study product for all reported RAI acts.

Statistical analysis

There is no control group for comparison in this study. The main goal was not to compare between the three different placebo modalities, but to obtain overall rates of acceptability, adherence, and safety of each modality. The selected sample size provides at least 90% power to rule out rates of acceptability or adherence below 70%.

Baseline characteristics are described for all enrolled participants. The study’s safety endpoint was evaluated among participants who received at least one of the study products (excluding any study periods when participants did not receive a product). The acceptability and adherence primary endpoints were evaluated among participants who received all three study products and completed the scheduled product use (which we refer to as the “per-protocol” subset), thus providing relevant data from all three periods of study. To support the generalizability of acceptability and adherence results, we compared baseline characteristics between participants in the per-protocol subset and those who were lost to follow-up.

For the safety endpoint, the proportion of participants with Grade 2 or higher related AEs is reported, along with a 95% confidence interval (CI) (Clopper-Pearson method). For adherence and acceptability endpoints, the proportion of participants classified as adherent, or who reported a high acceptability score, are also provided, along with 95% CIs.

To test for potential effects of the assigned sequence and/or sites in the overall acceptability and adherence, generalized linear mixed models with a logistic link function were used. The participant’s assigned sequence, site, and the modality used in the study period were included as fixed effects, with a random effect at the participant level to account for the cross-over design. To test if overall differences exist between sites or assigned sequences, omnibus likelihood ratio tests were used. No adjustment of p-values was performed.

Results

Demographics of enrolled participants

We screened 257 individuals across the seven study sites and enrolled 217 participants in five countries; 40 were not enrolled: 29 were not eligible, five were eligible but did not enroll, and six did not complete their screening (see Fig 1). Overall, the retention rates were above 90% for all study visits.

The mean age was 24.9 years (SD = 4.7), ranging from 18 to 35 years old. Most of the sample reported having a male sex indicator assigned at birth (n = 214; 99%). Twenty percent of the sample identified as a gender minority. Overall, 13 (14%) participants in the U.S sites identified as Hispanic/Latinx. The racial, ethnic, and tribal affiliation of participants across the study sites is noted in Table 2.

Table 2

| All Sites (N = 217) | Birmingham, USA (N = 33) | Pittsburgh, USA (N = 33) | San Francisco, USA (N = 30) | Blantyre, Malawi (N = 31) | Chiang Mai, Thailand (N = 30) | Johannesburg, South Africa (N = 30) | Lima, Peru (N = 30) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), M(SD) | 24.9 (4.7) | 25.7 (5.1) | 25.5 (4.8) | 28.6 (3.9) | 24.6 (4.6) | 23.3 (3.3) | 21.9 (3.0) | 24.7 (4.7) |

| Sex Assigned at Birth, N (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 214 (99%) | 31 (94%) | 32 (97%) | 30 (100%) | 31 (100%) | 30 (100%) | 30 (100%) | 30 (100%) |

| Female | 3 (1%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 173 (80%) | 28 (85%) | 28 (85%) | 27 (90%) | 19 (61%) | 22 (73%) | 28 (93%) | 21 (70%) |

| Female | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

| Transgender Male | 2 (1%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Transgender Female | 19 (9%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (27%) | 2 (7%) | 7 (23%) |

| Gender Nonconforming/ Variant | 5 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

| Other Gender | 10 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 9 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Multiple Genders | 6 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Latinx Ethnicity (U.S. Sites) | 13 (6%) | 2 (6%) | 3 (9%) | 8 (27%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Race (U.S. Sites) or Ethnic Group (non-U.S. sites) | ||||||||

| Asian | 8 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 6 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Black or African American | 16 (7%) | 13 (39%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (1%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| White | 66 (30%) | 19 (58%) | 28 (85%) | 19 (63%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Multiple Races | 33 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 30 (100%) |

| Thai | 30 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 30 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Xhosa | 5 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (17%) | 0 (0%) |

| Zulu | 14 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (47%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other African Ethnic Group | 38 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (23%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 6 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (13%) | 0 (0%) |

USA: United States of America

Participants reported having had an average of 3 male partners (SD = 6.35; range: 0–70) in the prior 30 days. Participants’ average total number of RAI occasions during that 30-day period was 4.76 (SD = 8.50; range: 0–100), with an average of 2.57 (SD = 7.74; range: 0–100) condomless RAI occasions self-reported during the same period. Two thirds of participants (n = 142; 65.4%) reported prior use of an enema, with fewer participants self-reporting that they had used a suppository (n = 8; 3.7%) or insert (n = 10; 4.6%) prior to RAI.

Study product use period completion

A study product use period was considered completed if the participant received the study product and completed the scheduled study product use period. Study product use period completion rates were 94% for the insert, 95% for the suppository, and 95% for the enema. Among enrolled participants, 92% exited the study at their scheduled end of study visit. Reasons for early study terminations included “Participant refused further participation” [n = 2 (1%)], “Participant is unwilling/unable to comply with required procedures” [n = 6 (3%)], “Lost to follow-up” [n = 4 (2%)], “Investigator decision” [n = 1 (<1%)], “Unable to contact participant” [n = 3 (1%)], “HIV infection” [n = 1 (<1%)], and “Other, specify” [n = 1 (<1%), participant relocating].

The per-protocol subset of participants (those who completed all three study product use periods) included 202 (93%) out of the 217 participants enrolled (see Fig 1). No major differences were observed in the baseline characteristics of these participants (site, randomization sequence, age, sex assigned at birth or gender) when compared to those of participants not included in the per-protocol subset.

Primary safety endpoint

There were 204 AEs in the study reported by 98 participants (45% of the total sample; see Table 3). One hundred sixty-seven (81.9%) were classified as not related to the study products, and the remaining 37 (18.1%) were classified as related to the study products and occurred in 24 (11.1%) of participants. Thirty-five product-related AEs were graded as mild; two were graded as moderate (our primary safety endpoint) and both occurred during periods of insert use. Product-related AEs included abdominal distention (n = 1), abdominal pain (n = 5), anal pruritus (graded as moderate, n = 1), anorectal discomfort (n = 7), constipation (n = 1), defecation urgency (n = 3), diarrhoea (n = 4), dyschezia (n = 1), flatulence (n = 6), nausea (n = 1), rectal haemorrhage (n = 1), rectal tenesmus (n = 4), and malaise (n = 2, one graded as moderate). No events were graded as potentially life-threatening or resulting in death. There were no pregnancies reported by participants in this study. Two participants tested positive for HIV infection during follow-up while enrolled in the study.

Table 3

| Total | Not Related | Related | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severity Grade | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Grade 1 Mild | 95 (46.6%) | 60 (63.2%) | 35 (36.8%) |

| Grade 2 Moderate | 107 (52.5%) | 105 (98.1%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| Grade 3 Severe | 2 (0.9%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Grade 4 Potentially Life-Threatening | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Grade 5 Death | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 204 (100%) | 167 (81.9%) | 37 (18.1%) |

Notes. 98 out of the 217 participants reported one or more AEs.

Primary acceptability endpoint

The proportion of participants reporting “high acceptability” was for inserts: 72% (95%CI: 65% - 78%), suppositories: 66% (95%CI: 59% - 73%), and enemas: 73% (95%CI: 66% - 79%) (see Table 4).

Table 4

| Acceptability | Adherence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectal Insert | Suppository | Rectal Enema | Rectal Insert | Suppository | Rectal Enema | |

| Percentage with High Acceptability/Adherence and 95% Confidence Interval | 72% (65%, 78%) | 66% (59%, 73%) | 73% (66%, 79%) | 75% (69%, 81%) | 74% (68%, 80%) | 83% (77%, 88%) |

| Participants with high acceptability/adherence by site | ||||||

| Birmingham, USA | 21/29 (72%) | 19/29 (66%) | 23/29 (79%) | 26/29 (90%) | 22/29 (76%) | 24/29 (83%) |

| Blantyre, Malawi | 24/29 (83%) | 21/29 (72%) | 26/29 (90%) | 23/29 (79%) | 16/29 (55%) | 20/29 (69%) |

| Chiang Mai, Thailand | 25/30 (83%) | 21/30 (70%) | 13/30 (43%) | 25/30 (83%) | 30/30 (100%) | 29/30 (97%) |

| Johannesburg, South Africa | 22/27 (81%) | 21/27 (78%) | 20/28 (71%) | 10/27 (37%) | 14/27 (52%) | 18/28 (64%) |

| Lima, Peru | 18/26 (69%) | 18/26 (69%) | 23/25 (92%) | 22/26 (85%) | 19/26 (73%) | 22/25 (88%) |

| Pittsburgh, USA | 17/30 (57%) | 16/30 (53%) | 23/30 (77%) | 20/30 (67%) | 23/30 (77%) | 26/30 (87%) |

| San Francisco, USA | 16/30 (53%) | 16/30 (53%) | 15/30 (50%) | 24/30 (80%) | 24/30 (80%) | 26/30 (87%) |

Notes. Estimates exclude missing data for acceptability (Rectal insert (n = 3); Suppository (n = 2); Enema (n = 5)) and adherence (Rectal insert (n = 3); Suppository (n = 3); Enema (n = 2)).

From the logistic mixed model (see Table 5), no statistically significant differences in product acceptability were observed between products. Participants in Birmingham, Blantyre, Johannesburg, and Lima being more likely (between 2.74 and 6.42 times more likely) to report high acceptability than participants in San Francisco. No significant differences were observed by product sequence.

Table 5

| Acceptability | Adherence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio Estimate | Lower CI | Upper CI | p-value | Odds Ratio Estimate | Lower CI | Upper CI | p-value | |

| Product | ||||||||

| Enema | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Insert | .97 | .60 | 1.57 | .90 | .51 | .28 | .94 | .03 |

| Suppository | .69 | .43 | 1.11 | .13 | .49 | .26 | .89 | .02 |

| Site | ||||||||

| San Francisco, USA | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Birmingham, USA | 2.74 | 1.24 | 6.07 | .01 | 1.06 | .28 | 3.96 | .93 |

| Blantyre, Malawi | 6.42 | 2.60 | 15.83 | < .001 | .33 | .09 | 1.16 | .08 |

| Chiang Mai, Thailand | 1.94 | .90 | 4.17 | .09 | 3.52 | .83 | 14.97 | .09 |

| Johannesburg, South Africa | 4.36 | 1.85 | 10.29 | .001 | .10 | .03 | .38 | .001 |

| Lima, Peru | 3.47 | 1.49 | 8.06 | .004 | .89 | .23 | 3.38 | .86 |

| Pittsburgh, USA | 1.65 | .77 | 3.52 | .20 | .67 | .19 | 2.41 | .54 |

| Sequence Order | ||||||||

| A | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| B | 1.52 | .68 | 3.39 | .31 | .99 | .30 | 3.32 | .99 |

| C | .80 | .38 | 1.72 | .57 | 1.25 | .38 | 4.12 | .71 |

| D | .91 | .42 | 1.96 | .81 | .79 | .24 | 2.56 | .69 |

| E | 1.01 | .47 | 2.18 | .98 | 1.02 | .31 | 3.35 | .97 |

| F | .91 | .42 | 1.97 | .80 | 1.50 | .44 | 5.10 | .51 |

Note. Rectal enema, the San Francisco site, and sequence A are used as reference levels for study product, site, and randomized sequence, respectively.

Primary adherence endpoint

The adherence primary endpoint was evaluated on the per-protocol subset of 202 participants (see Table 4). The proportion of participants reporting full adherence per protocol was: inserts 75% (95%CI: 69% - 81%), suppositories: 74% (95%CI: 68% - 80%), and enemas: 83% (95%CI: 77% - 88%).

As noted in Table 5, the observed differences in adherence per protocol across products were statistically significant. Statistically significant differences were also observed between some sites, with participants in the Johannesburg site were also less likely to be fully adherent when compared to their peers in San Francisco. Assigned product sequence was not associated with adherence.

Adherence per-sex-act

Participants in the per-protocol subset reported an average of about 7 sex acts in the 4-week period of product use: insert (M = 7.2; SE = 0.7), suppository (M = 7.7; SE = 0.7), and enema (M = 7.8; SE = 0.8). Among participants who reported at least one sex act during the product use period, the percentages of participants fully adherent per RAI-act were similar among the three study products: insert (n = 99/168; 58.9%), suppository (n = 101/174; 58.0%) and enema (n = 107/182; 58.8%).

Discussion

RMs are needed for individuals with an increased chance of acquiring HIV through RAI, particularly young SGM across the globe [23]. Given ongoing challenges to ensure equitable uptake and adherence to systemic oral PrEP and the desire for a diverse suite of HIV prevention products, it is important to expand the HIV/STI prevention pipeline by exploring whether different types of products that could be delivered through various modalities are safe, acceptable and adherable, and behaviorally congruent with the intended end-users’ RAI practices [9].

All three administration modalities with placebo products were found to be safe for use, with less than 20% of AEs deemed related to the study products/modalities and only two related events being graded as having moderate clinical severity or higher. These findings align with our study hypothesis. The safety profile of all three administration modalities with placebo products is promising and underscores the potential of all three modalities as viable for rectal drug delivery. The low incidence of distinct product-related AEs (e.g., diarrhea, flatulence) across study products is also noteworthy, as it mirrors common AEs reported when using over-the-counter rectal products (e.g., enemas) and prior rectal microbicide candidates in clinical trials (e.g., gels). while we should continue to reduce the occurrence of any AEs during product development, the promising safety profiles for the three modalities using placebo products employed in this trial offer a threshold whereby future clinical trials examining these same modalities with active drug ingredients can benchmark their safety endpoints.

Consistent with our hypotheses for our acceptability and adherence endpoints, SGM participants reported high overall acceptability for all three products and high overall adherence per protocol and per RAI act. While survey research literature has noted high hypothetical acceptability to RMs as an HIV prevention strategy prior to RAI [9, 14, 15, 17, 20, 24, 32], there has been limited research exploring the real-world acceptability and adherence of these three products. The absence of these data is troubling from a product development perspective given the increasingly restrictive costs and resources required to empirically evaluate a promising biomedical HIV prevention candidate. In the absence of product acceptability and adherence data, the effectiveness of a PrEP candidate may be compromised if the intended end-users are not willing to use it. Future research examining the acceptability of and adherence to diverse PrEP candidates should remain a priority in clinical trials.

While overall acceptability and adherence were high for each product, we observed differences in acceptability and adherence after SGM participants had used all three modalities. While the products were rated similarly in their acceptability and there were no differences based on participants’ assigned product sequence, adherence to the enema was higher when compared to the fast-dissolving insert or the suppository. Given the high prevalence of rectal douching prior to RAI among SGM globally [33], the greater adherence to the enema may be indicative of congruence between the benefits afforded by the modality and users’ behavioral practices prior to RAI. In a recent study, for instance, Carballo-Diéguez and colleagues [21] found that over 80% of SGM participants reported douching prior to RAI to rinse their rectum and feel clean, avoid smelling bad, and/or enhance their sexual pleasure. Given the limited data on the use of inserts or suppositories by SGM populations, however, it is unclear if these products could also yield behaviorally congruent benefits prior to or during RAI, including increasing sexual pleasure and lubricity during sex, and result in greater adherence in future studies.

We also observed differences for both acceptability and adherence between participants living in the different communities across the five countries participating in the trial. Compared to San Francisco, participants in the other regions reported greater acceptability of the three rectal modalities under study. Consistent with prior research with hypothetical and real-world studies with rectal candidates [9, 13, 26, 34], these regional variations suggest that some modalities may be more acceptable or adherable in some contexts than others. It is possible that this difference in acceptability may be related to the various efficacious PrEP modalities already available in San Francisco (e.g., daily, and event-driven oral PrEP) and which may not be available or accessible in other regions. As such, participants in the San Francisco site may weigh acceptability differently given their ability to compare these placebo modalities against efficacious PrEP technologies. We also found differential adherence between participants in the San Francisco and the Johannesburg sites; however, it is unclear what may have contributed to these differences. Although the collected data suggests differences by sites, future research, both qualitative and quantitative, may be warranted given the number of comparisons and the absence of clear hypotheses to understand the factors contributing to these differences.

Strengths & limitations

This study had several strengths. First, this is the first study to examine the safety and acceptability of and adherence to these three promising modalities for rectal drug delivery prior to RAI. Examining each product’s use in real life contexts strengthens the social validity of our findings and the potential use for these three modes of delivery in the future. Second, the crossover randomized design of our trial allowed us to assess SGM participants’ acceptability of and adherence to these three modalities within the same trial, offering a unique opportunity to compare their acceptability, safety, and adherence within individuals who used all three products prior to RAI. Third, given the variability in both legal protections and social acceptance of SGM people between and within these countries, our ability to recruit and retain a large sample of young SGM living in geographically and socio-politically diverse countries is noteworthy and strengthens the generalizability of our findings to diverse contexts. Finally, our efforts to minimize the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic during our data collection period minimized interruptions to our trial and ensured that rigor was preserved [27].

Nonetheless, our trial also had several limitations. First, self-reported responses tend to be favorable due to social desirability; however, we tried to minimize bias by having participants complete their questionnaires in a private location during their clinical visits. Second, there is a possibility of recall bias when participants completed their surveys. Third, we recruited a convenience sample of participants willing to use each of the study products at least once per week, as required by the protocol. We acknowledge that the generalizability of our clinical trial findings may not be representative of all individuals practicing RAI. Fourth, given the placebo nature of the three products used in our trial, we were unable to employ a biological confirmation method regarding participants’ product use and adherence, or examine the extent and duration of rectal coverage afforded by each product during and after sex. These data will be crucial in the future, particularly as drug candidates are embedded into these modalities and tested for safety and adherence. Fifth, we were unable to recruit the sexual partners of our study participants. Given existing data regarding partners’ roles in young SGMs’ decision-making when selecting HIV prevention strategies prior to sex, future research examining these dyadic dynamics may be warranted. Finally, while we designed our clinical trial to resemble participants’ product use to as close as ‘real-world’ settings possible while maintaining rigor, we acknowledge that the trial protocols may hinder the social validity of the findings. Future research examining these products in real-world situations may further clarify their potential for use as rectal microbicide modalities.

Conclusions

Advances in biomedical strategies for HIV prevention continue to emerge. Efforts to diversify HIV prevention options will strengthen our ability to reduce new HIV infections among SGM, whether some SGM desire systemic modalities (e.g., daily oral PrEP; PrEP injectables) or prefer topical protection (e.g., RMs). Regardless of the mode of administration, the effectiveness of these HIV prevention strategies will require that users have access to safe and acceptable products which are easy to use consistently. Our trial addresses the limited data available regarding the safety and acceptability of and adherence to enemas, inserts, and suppositories as potential modalities through which to deliver a rectal microbicide. findings from this trial demonstrate high safety profiles, alongside high levels of acceptability and adherence, among all three modalities. future research examining the acceptability, adherence, safety, and efficacy of promising prep candidates using these three rectal microbicide modalities is encouraged.

Supporting information

S1 Checklist

CONSORT checklist for MTN-035 trial.(DOC)

Acknowledgments

The study team gratefully acknowledges the study participants of MTN-035. We are grateful to the local research teams for their work. We also recognize the contributions of staff across the study sites. In Malawi, we recognize the work of Abigail Mnemba, Alinafe Kamanga, Annie Munthali, Daniel Gondwe, Linly Seyama, Yamikani Mbilizi, Noel Kayange, Mary Chadza, and Josiah Mayani. In South Africa, the MTN-035 team included Helen Rees, Kerushini Moodley, Krishnaveni (Krina) Reddy, Thesla Palanee-Phillips, Andile Twala, Ashleigh Jacques, Tsitsi Nyamuzihwa, Nazneen Cassim. In Peru, we recognize the work of Ana Miranda, Diana Morales, Helen Chapa, Javier Valencia, Milagros Sabaduche, Pedro Gonzales, Karina Pareja, Katherine Milagros, and Charri Macassi. We also recognize the Thailand MTN-035 team, including the work by Suwat Chariyalertsak, Pongpun Saokhieo, Veruree Manoyos, Nataporn Kosachunhanan, and Piyathida Sroysuwan. In the United States, we recognize the work of Allison Matthews, Amy Player, Andrea Thurman, Carol Mitchell, Christine O’Neill, Christy Pappalardo, Christopher Quan, Cindy Jacobson, Clifford Yip, Craig Hendrix, Craig Hoesley, Danielle Camp, Deon Powell, Devika Singh, Diana Ng, Edward Livant, Elizabeth Brown, Emily Helms, Emily Schaeffer, Faye Heard, Gina Brown, Gustavo Doncel, Holly Gundacker, Hyman Scott, Jackie Fitzpatrick, James Gavel, Jeanna Piper, Jenna Weber, Jennifer Schille, Jessica Webster, Jessica Maitz, Jillian Zemanek, Jim Pickett, Jonathan Lucas, Julie Nowak, Kathleen Dietz, Ken Ho, Krissa Welch, Kristine Heath, Lisa Rohan, Lizardo Lacanlale, Lynn Mitterer, Lorna Richards, Marcus Bolton, Mei Song, Naana Cleland, Nicholas Ng, Nicole Macagna, Nnennaya Okey-Igwe, Onkar Singh, Patricia Peters, Rebecca Giguere, Renee Weinman, Roberta Black, Scott Fields, Sharon Riddler, Sharon Hillier, Sherri Karas, Sherri Johnson, Stacey Edick, Sufia Dadabhai, Susan Buchbinder, Taha Taha, Tarana Billups, Teri Senn, Theresa Wagner, Tim McCormick, and Yuqing Jiao. The rectal placebo inserts used in this study were provided by CONRAD as part of a project entitled Development of Novel On-Demand and Longer-Acting Microbicide Product Leads funded by a cooperative agreement between the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and Eastern Virginia Medical School (AID-OAA-A-14-00010).

Funding Statement

The study was designed and implemented by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN; https://mtnstopshiv.org/research/studies/mtn-035). From 2006 until November 30, 2021, the MTN was an HIV/AIDS clinical trial network funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615, UM1AI106707), with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. NIH employees contributed to the study design, manuscript development and the decision to publish as well as providing safety oversight during study conduct but had no role in data collection and analysis.

Data Availability

Data cannot be shared publicly as some fields may include identifiable Protected Health Information (PHI). Requests for de-identified datasets are available from the Microbicide Trials Network. A Dataset Request Form must be completed by the investigator requesting the data; the completed form must be then be submitted to the FHI 360 Clinical Research Manager (CRM) for the protocol. The data underlying the results presented in the study are available from the MTN. Data supporting the study findings were provided by the trial team of the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN) 035. Data are restricted and are not publicly available. Parties interested in accessing the MTN 035 data may contact the MTN Leadership Team at gro.vihspotsntm@rgmmdantm for access to de-identified data.

References

Decision Letter 0

12 Jan 2023

PONE-D-22-27511A Randomized Trial of Safety, Acceptability and Adherence of Three Rectal Microbicide Placebo Formulations among Young Sexual and Gender Minorities Who Engage in Receptive Anal Intercourse (MTN-035)PLOS ONE

Dear Dr. Bauermeister,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands. Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process.

The manuscript has been evaluated by three reviewers, and their comments are available below.

Overall, the reviewers have expressed their congratulations on the quality of the manuscript and have offered several suggestions to further enhance the study methodology. In particular, they have noted that the study population and eligibility criteria were not described in enough detail to allow for replication of the study. As a result, the reviewers have raised concerns about the generalizability of the results. The full details of their comments may be seen below.

Could you please revise the manuscript to carefully address the concerns raised?

Please submit your revised manuscript by Feb 25 2023 11:59PM. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp. When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

Please include the following items when submitting your revised manuscript:

A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). You should upload this letter as a separate file labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Manuscript'.

If you would like to make changes to your financial disclosure, please include your updated statement in your cover letter. Guidelines for resubmitting your figure files are available below the reviewer comments at the end of this letter.

If applicable, we recommend that you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io to enhance the reproducibility of your results. Protocols.io assigns your protocol its own identifier (DOI) so that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols. Additionally, PLOS ONE offers an option for publishing peer-reviewed Lab Protocol articles, which describe protocols hosted on protocols.io. Read more information on sharing protocols at https://plos.org/protocols?utm_medium=editorial-email&utm_source=authorletters&utm_campaign=protocols.

We look forward to receiving your revised manuscript.

Kind regards,

Lucinda Shen, MSc

Staff Editor

PLOS ONE

Journal Requirements:

When submitting your revision, we need you to address these additional requirements.

1. Please ensure that your manuscript meets PLOS ONE's style requirements, including those for file naming. The PLOS ONE style templates can be found at

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=wjVg/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_main_body.pdf and

2. Thank you for stating the following financial disclosure:

“The study was designed and implemented by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN). From 2006 until November 30, 2021, the MTN was an HIV/AIDS clinical trial network funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615, UM1AI106707), with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.”

Please state what role the funders took in the study. If the funders had no role, please state: "The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript."

If this statement is not correct you must amend it as needed.

Please include this amended Role of Funder statement in your cover letter; we will change the online submission form on your behalf.

3. Thank you for stating the following in the Competing Interests section:

“I have read the journal's policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: Dr. Liu has received funding for investigator sponsored research projects from Gilead Sciences and Viiv Healthcare. Gilead Sciences has donated study drug to studies led by Dr. Liu.”

Please confirm that this does not alter your adherence to all PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials, by including the following statement: "This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.” (as detailed online in our guide for authors http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/competing-interests). If there are restrictions on sharing of data and/or materials, please state these. Please note that we cannot proceed with consideration of your article until this information has been declared.

Please include your updated Competing Interests statement in your cover letter; we will change the online submission form on your behalf.

4. Please review your reference list to ensure that it is complete and correct. If you have cited papers that have been retracted, please include the rationale for doing so in the manuscript text, or remove these references and replace them with relevant current references. Any changes to the reference list should be mentioned in the rebuttal letter that accompanies your revised manuscript. If you need to cite a retracted article, indicate the article’s retracted status in the References list and also include a citation and full reference for the retraction notice.

[Note: HTML markup is below. Please do not edit.]

Reviewers' comments:

Reviewer's Responses to Questions

Comments to the Author

1. Is the manuscript technically sound, and do the data support the conclusions?

The manuscript must describe a technically sound piece of scientific research with data that supports the conclusions. Experiments must have been conducted rigorously, with appropriate controls, replication, and sample sizes. The conclusions must be drawn appropriately based on the data presented.

Reviewer #1: Yes

Reviewer #2: Yes

Reviewer #3: Yes

**********

2. Has the statistical analysis been performed appropriately and rigorously?

Reviewer #1: Yes

Reviewer #2: Yes

Reviewer #3: Yes

**********

3. Have the authors made all data underlying the findings in their manuscript fully available?

The PLOS Data policy requires authors to make all data underlying the findings described in their manuscript fully available without restriction, with rare exception (please refer to the Data Availability Statement in the manuscript PDF file). The data should be provided as part of the manuscript or its supporting information, or deposited to a public repository. For example, in addition to summary statistics, the data points behind means, medians and variance measures should be available. If there are restrictions on publicly sharing data—e.g. participant privacy or use of data from a third party—those must be specified.

Reviewer #1: Yes

Reviewer #2: No

Reviewer #3: No

**********

4. Is the manuscript presented in an intelligible fashion and written in standard English?

PLOS ONE does not copyedit accepted manuscripts, so the language in submitted articles must be clear, correct, and unambiguous. Any typographical or grammatical errors should be corrected at revision, so please note any specific errors here.

Reviewer #1: Yes

Reviewer #2: Yes

Reviewer #3: Yes

**********

5. Review Comments to the Author

Please use the space provided to explain your answers to the questions above. You may also include additional comments for the author, including concerns about dual publication, research ethics, or publication ethics. (Please upload your review as an attachment if it exceeds 20,000 characters)

Reviewer #1: This paper summarized the results of a RCT to assess acceptability and adherence to three methods for self-administering rectal microbicide PrEP for the prevention of HIV transmission via receptive anal sex. The paper is thorough in its description of methods and well written. I mostly have minor comments and points of clarification.

Methods

Eligibility criteria: What does "ability and willingness to provide adequate locator information" mean?

Eligibility criteria: How was "general good health" assessed?

This is more editorial, but there are a number of unusual acronyms (e.g., RM, PUEV) that reduce readability.

Results

Page 14: First paragraph under Study Product Use Period Completion: In one instance n = 1 is reported as 1%, in another n = 1 is reported as <1%.

Logistic mixed model results: There is a substantial difference in acceptability in the methods based on the point estimates here that is not clear in the raw estimates of acceptability. The authors address possible reasons for differences in acceptability by site in the discussion, but the models account for site. The confidence intervals are relatively wide, as well. Was the study powered for these analyses? Additional discussion about these points is warranted.

Reviewer #2: This study aimed to evaluate the safety, acceptability and adherence of three rectal microbicide placebo formulations for young sexual and gender minorities who engage in receptive anal intercourse. It is important to develop effective products such as these to complement currently available products such as oral PrEP and condoms. The paper is well written and detailed. However I do have some issues to raise.

Major comments

1. It would help to have more detailed characterisation of the study population. The cross-over procedure is explained in great detail, but the population is referred to as “sexual and gender minorities” without really explaining this, and the baseline characteristics table does not give sufficient detail either, only including gender and sex at birth, but not information such as MSM status or frequency of RAI practice.

2. The compliance is extremely high, given the number of visits required, the number of invasive procedures and that at least some of the study was conducted during the pandemic. I would like to see further detail of how this was achieved, and even more importantly, how generalisable are these results? I can’t imagine that the study participants are representative of all those who practise RAI, or even “sexual and general minorities” populations specifically. I imagine acceptability and adherence would be considerably lower in populations less able to commit to the study schedule. Related to this, I feel that the recruitment procedure is skimmed over. How were individuals currently practising RAI targeted? So few individuals were excluded because they did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. One inclusion criterion is “a reported history of consensual RAI at least three times in the past three months”? How was that ascertained without administering some kind of pre-recruitment questionnaire as part of the screening process?

3. It’s important to set out differences in results by setting more clearly. The authors provide odds ratios in Table 5 but no acceptability/adherence percentages stratified by setting. It’s important to understand how much acceptability and adherence vary by setting, so we have an idea how generalisable results may be between settings for future studies.

4. The abstract doesn’t seem to talk about any differences in outcomes between the three products, even though the results showed that the enema had a higher adherence than the other products.

5. Limitations section of Discussion: I think this should be extended. Following on from point 3 re generalisability, I think authors should comment on other populations practising RAI such as heterosexual women. The study population here was almost universally individuals born male. Participants were instructed on how to use the products and first used them in the clinic – is there any comment on potential for misuse of products if users are provided with written instructions only/guidance videos etc? Authors talk about “real-world acceptability” but the conditions in this study are very far from how such products would be used in a real-world situation. Are they really reaching the “intended end-users”? Authors mention social desirability bias but was there risk of recall bias (top page 12: “Thinking about your experience during these past four weeks, in how many of the weeks did you miss a rectal [study product] application?”?

6. Any study such as this, evaluating acceptability, cries out for a mixed methods design. This study really suffers from having no qualitative research component to start to understand and interpret the quantitative outcomes. Additionally, at the many clinic visits, there would have been opportunity to ask pertinent closed and open-ended questions. Instead, there is quite a lot of conjecture in the Discussion which could have been answered with better questionnaire design e.g., enema use and user’s practices prior to RAI. Authors could have asked participants about these practices. Authors also mention that San Francisco-based participants may already have access to other PrEP products which may be responsible for the differences in acceptability by setting. One of the study questionnaires could have asked about this. This weakness needs to be acknowledged in the Limitations section.

7. I wanted to see a lot more detail on RAI activity, including how many weeks participants reported no RAI. I’d have liked to see this in a table with frequency of RAI activity by baseline characteristics.

Minor comments

1. There are quite a few abbreviations that I wouldn’t consider necessary such as AEs, RMs, SGM and PUEVs.

2. Figure 1 refers to “douche” rather than “enema”. It also seems overly complicated.

3. Abstract: it may be clearer if the abstract was structured (IMRAD format). “204 adverse events were reported by 98 participants” – provide percentage of participants reporting at least one adverse event.

4. “The efficacy and effectiveness of emerging HIV prevention drug depends” – shouldn’t this be “HIV prevention products depend”?

5. Introduction line 4: provide references for HIV prevalence by region statistics.

6. Introduction paragraph 1 last sentence: shouldn’t it be “drugs targeting multiple STIs” rather than “multiple drugs”?

7. Page 5 last sentence: any references at all for the “few studies with SGM populations have examined the acceptability, uptake of, and adherence to inserts, suppositories, or enemas”?

8. The countries included should be stated in the abstract.

9. First line of page 7: this should really be in the Results section.

10. Figure 1 seems overly detailed, and there’s a lot of overlap with Table 1 – they can probably be combined. I think it should show the 1 week wash-out period in some way.

11. Jacobson et al are mentioned (top page 11): please describe more about the overlap between papers and what further information Jacobson et al provides that would be useful to the reader when interpreting this paper.

12. Adherence per sex act (page 16): shouldn’t this be referring to “per RAI act” rather than just “per sex act”?

13. Discussion Strengths and Limitations paragraph 2: provide percentages for adherence per protocol and per sex act, and then the percentages for hypothetical acceptability reported by all the other studies that are cited, for comparison.

14. Page 18 first sentence: “users’ behavioural practices prior to sex” – should be “prior to RAI”. Authors should be careful about these distinctions throughout the manuscript.

15. Table 2 row headers: add country for each setting.

16. Table 2 states that 100% of Blantyre participants were “Other African tribe” ethnicity. Surely, as 100% of participants from this site were from this one group, this could be more specific?

17. Table 4 label “95% Confidence Interval” doesn’t seem quite right, as there’s a central estimate then 95%CI in brackets.

Reviewer #3: This is a generally well-conducted study. There are some aspects of the reporting that could be improved. In particular, I would recommend that the authors adhere to the CONSORT guidelines. For example, the first paragraph under "methods" reports results, which should be in the results section. Instead they could have began by describing the study design, followed by eligibility, study procedures, and outcomes. One key element which is completely omitted is how the study sample size was determined - this should be reported. The statistical analysis seems mostly okay; one minor suggestion is to report standard errors instead of standard deviations in the analysis of "adherence per-sex-act" (but keep standard deviations elsewhere where they have been reported for descriptive purposes).

**********

6. PLOS authors have the option to publish the peer review history of their article (what does this mean?). If published, this will include your full peer review and any attached files.

If you choose “no”, your identity will remain anonymous but your review may still be made public.

Do you want your identity to be public for this peer review? For information about this choice, including consent withdrawal, please see our Privacy Policy.

Reviewer #1: No

Reviewer #2: No

Reviewer #3: No

**********

[NOTE: If reviewer comments were submitted as an attachment file, they will be attached to this email and accessible via the submission site. Please log into your account, locate the manuscript record, and check for the action link "View Attachments". If this link does not appear, there are no attachment files.]

While revising your submission, please upload your figure files to the Preflight Analysis and Conversion Engine (PACE) digital diagnostic tool, https://pacev2.apexcovantage.com/. PACE helps ensure that figures meet PLOS requirements. To use PACE, you must first register as a user. Registration is free. Then, login and navigate to the UPLOAD tab, where you will find detailed instructions on how to use the tool. If you encounter any issues or have any questions when using PACE, please email PLOS at gro.solp@serugif. Please note that Supporting Information files do not need this step.

Author response to Decision Letter 0

15 Feb 2023

Reviewer 1

This paper summarized the results of a RCT to assess acceptability and adherence to three methods for self-administering rectal microbicide PrEP for the prevention of HIV transmission via receptive anal sex. The paper is thorough in its description of methods and well written. I mostly have minor comments and points of clarification.

• Thank you. We have clarified the points raised below.

Eligibility criteria. What does "ability and willingness to provide adequate locator information" mean? How was "general good health" assessed?

• We appreciate the Reviewer catching the typo on our inclusion criteria. We now clarify that participants had to be able and willing to provide “adequate contact and location information”. We also clarify that they had to be “deemed in general good health by a healthcare provider at Screening and Enrollment”.

Acronyms. This is more editorial, but there are a number of unusual acronyms (e.g., RM, PUEV) that reduce readability.

• Thank you. We have reduced abbreviations (i.e., RM and PUEV) to improve readability wherever possible.

Prevalence. Page 14: First paragraph under Study Product Use Period Completion: In one instance n = 1 is reported as 1%, in another n = 1 is reported as <1%.

• Thank you. We should have used <1%. This was updated in our revised manuscript.

Logistic mixed model results: There is a substantial difference in acceptability in the methods based on the point estimates here that is not clear in the raw estimates of acceptability. The authors address possible reasons for differences in acceptability by site in the discussion, but the models account for site. The confidence intervals are relatively wide, as well. Was the study powered for these analyses? Additional discussion about these points is warranted.

• We would like to address the apparent difference in acceptability from the logistic model relative to raw estimates. Although raw estimates of the Odds Ratios (OR) are not provided in the manuscript, they are in fact not very different from those obtained from the adjust logistic model:

OR(Insert vs Enema) = [0.72/(1-0.72)]/[0.73/(1-0.73)] = 0.95 (Adjusted OR = 0.97)

OR(Suppositories vs Enema) = [0.66/(1-0.66)]/[0.73/(1-0.73)] = 0.72 (Adjusted OR = 0.69)

We hope that the reviewer will agree that is the use of a different scale (odds ratio) what gives the impression of a more substantial difference between some of the modalities, rather than it being a consequence of including adjustment of other factors in the logistic model. That said, we would like to clarify that the principal objective of the study was not to compare the different modalities, but to evaluate the acceptability and adherence of each one and to provide estimates. While the sample size of the study allowed for high power for ruling out acceptability/adherence rates below 70%, the study was not powered for formal comparisons between modalities. The logistic regression model analysis was performed to test for any potential differences by randomize sequence (to check for possible effect of the order in which participants used the products, or possible carry-over effect), and (ii) to test for the differences observed between sites. While we think it reasonable to include the study product in these models (which in turns allowed us to make some statements regarding some of the differences being statistically significant), we acknowledge that failing to declare some of the differences as significant does not imply the absence of such differences. To avoid confusion, the Statistical Analysis section of the Methods has been updated to clarify the main objective of the study. We have also removed some statements previously included in the Results section, which probably unduly emphasized these statistical tests.

Reviewer #2

This study aimed to evaluate the safety, acceptability and adherence of three rectal microbicide placebo formulations for young sexual and gender minorities who engage in receptive anal intercourse. It is important to develop effective products such as these to complement currently available products such as oral PrEP and condoms. The paper is well written and detailed. However I do have some issues to raise.

• Thank you for your review. We respond to the points raised below, as well as in the manuscript.

Description of the study population. It would help to have more detailed characterisation of the study population. The cross-over procedure is explained in great detail, but the population is referred to as “sexual and gender minorities” without really explaining this, and the baseline characteristics table does not give sufficient detail either, only including gender and sex at birth, but not information such as MSM status or frequency of RAI practice.

• We have now provided a definition of sexual gender minorities (i.e., populations with same-sex or same-gender attractions or behaviors and who may identify with a non-heterosexual identity such as gay, bisexual, queer, etc.) in the Introduction.

• Thank you. We note that the sample’s baseline sexual behaviors as part of their Inclusion criteria (i.e., individuals self-report engaging in consensual receptive anal sex at least three times in the past three months and have the expectation to maintain at least that frequency of RAI during study participation). As requested, we have also included additional baseline information regarding participants’ sexual behaviors in the prior 30 days and prior history with the three study products in the Results:

“Participants reported having had an average of 3 male partners (SD=6.35; range: 0-70) in the prior 30 days. Participants’ average total number of RAI occasions during that 30-day period was 4.76 (SD=8.50; range: 0-100), with an average of 2.57 (SD=7.74; range: 0-100) condomless RAI occasions self-reported during the same period. Two thirds of participants (n=142; 65.4%) reported prior use of an enema, with fewer participants self-reporting that they had used a suppository (n=8; 3.7%) or insert (n=10; 4.6%) prior to RAI.”

Generalizability of results. The compliance is extremely high, given the number of visits required, the number of invasive procedures and that at least some of the study was conducted during the pandemic. I would like to see further detail of how this was achieved, and even more importantly, how generalisable are these results? I can’t imagine that the study participants are representative of all those who practise RAI, or even “sexual and general minorities” populations specifically. I imagine acceptability and adherence would be considerably lower in populations less able to commit to the study schedule.

• We agree that participants in a clinical trial may not be representative of the general population. We have expanded the limitations section to highlight this point. Specifically, we now state: “Second, we recruited a convenience sample of participants willing to use each of the study products at least once per week, as required by the protocol. We acknowledge that the generalizability of our clinical trial findings may not be representative of all individuals practicing RAI.”

Recruitment and screening. Related to this, I feel that the recruitment procedure is skimmed over. How were individuals currently practising RAI targeted? So few individuals were excluded because they did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. One inclusion criterion is “a reported history of consensual RAI at least three times in the past three months”? How was that ascertained without administering some kind of pre-recruitment questionnaire as part of the screening process?

• Thank you. We have expanded the recruitment paragraph to highlight the procedures that different sites undertook. We now state: Participants were recruited from a variety of sources, including outpatient clinics, universities, community-based locations, online websites, and social networking applications. In addition, participants were also referred to the study from other local research projects, research registries and other health and social service providers. At some sites, prospective participants were pre-screened by phone, using an IRB-approved phone script, to assess presumptive eligibility based on select behavioral and medical eligibility requirements. This includes a review of the prospective participants’ sexual history and engagement in receptive anal sex in their lifetime and within the previous three months. For those deemed presumably eligible when a phone screen was conducted, a screening visit was scheduled. A re- affirmation of all eligibility criteria was obtained and confirmed during a formal screening and enrollment visit, described below.

Differences in results. It’s important to set out differences in results by setting more clearly. The authors provide odds ratios in Table 5 but no acceptability/adherence percentages stratified by setting. It’s important to understand how much acceptability and adherence vary by setting, so we have an idea how generalisable results may be between settings for future studies.

• Thank you. We have added results by-site in Table 4.

Abstract. The abstract doesn’t seem to talk about any differences in outcomes between the three products, even though the results showed that the enema had a higher adherence than the other products.

• Thank you. We would like to clarify that the principal objective of the study was not to compare the different modalities, but to evaluate the acceptability and adherence of each one and to provide estimates. While the sample size of the study allowed for high power for ruling out acceptability/adherence rates below 70%, the study was not powered for formal comparisons between modalities. Therefore, we have not included this detail in the abstracts to avoid misdirecting the reader.

Limitations section of Discussion: I think this should be extended. Following on from point 3 re generalisability, I think authors should comment on other populations practising RAI such as heterosexual women. The study population here was almost universally individuals born male. Participants were instructed on how to use the products and first used them in the clinic – is there any comment on potential for misuse of products if users are provided with written instructions only/guidance videos etc? Authors talk about “real-world acceptability” but the conditions in this study are very far from how such products would be used in a real-world situation. Are they really reaching the “intended end-users”? Authors mention social desirability bias but was there risk of recall bias (top page 12: “Thinking about your experience during these past four weeks, in how many of the weeks did you miss a rectal [study product] application?”?

• Thank you for these comments. We have amended the Limitations section to note the potential for recall bias: “Second, there is a possibility of recall bias when participants completed their surveys.”. We have also made a note regarding the need for future research outside of a clinical trial design: “Finally, while we designed our clinical trial to resemble participants’ product use to as close as ‘real-world’ settings possible while maintaining rigor, we acknowledge that the trial protocols may hinder the social validity of the findings. Future research examining these products in real-world situations may further clarify their potential for use as rectal microbicide modalities.”