Abstract

Importance

Food allergies affect approximately 8% of children and 11% of adults in the US. Racial differences in food allergy outcomes have previously been explored among Black and White children, but little is known about the distribution of food allergies across other racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic subpopulations.Objective

To estimate the national distribution of food allergies across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups in the US.Design, setting, and participants

In this cross-sectional survey study, conducted from October 9, 2015, to September 18, 2016, a population-based survey was administered online and via telephone. A US nationally representative sample was surveyed. Participants were recruited using both probability- and nonprobability-based survey panels. Statistical analysis was performed from September 1, 2022, through April 10, 2023.Exposures

Demographic and food allergy-related participant characteristics.Main outcomes and measures

Stringent symptom criteria were developed to distinguish respondents with a "convincing" food allergy from those with similar symptom presentations (ie, food intolerance or oral allergy syndrome), with or without physician diagnosis. The prevalence of food allergies and their clinical outcomes, such as emergency department visits, epinephrine autoinjector use, and severe reactions, were measured across race (Asian, Black, White, and >1 race or other race), ethnicity (Hispanic and non-Hispanic), and household income. Complex survey-weighted proportions were used to estimate prevalence rates.Results

The survey was administered to 51 819 households comprising 78 851 individuals (40 443 adults and parents of 38 408 children; 51.1% women [95% CI, 50.5%-51.6%]; mean [SD] age of adults, 46.8 [24.0] years; mean [SD] age of children, 8.7 [5.2] years): 3.7% Asian individuals, 12.0% Black individuals, 17.4% Hispanic individuals, 62.2% White individuals, and 4.7% individuals of more than 1 race or other race. Non-Hispanic White individuals across all ages had the lowest rate of self-reported or parent-reported food allergies (9.5% [95% CI, 9.2%-9.9%]) compared with Asian (10.5% [95% CI, 9.1%-12.0%]), Hispanic (10.6% [95% CI, 9.7%-11.5%]), and non-Hispanic Black (10.6% [95% CI, 9.8%-11.5%]) individuals. The prevalence of common food allergens varied by race and ethnicity. Non-Hispanic Black individuals were most likely to report allergies to multiple foods (50.6% [95% CI, 46.1%-55.1%]). Asian and non-Hispanic White individuals had the lowest rates of severe food allergy reactions (Asian individuals, 46.9% [95% CI, 39.8%-54.1%] and non-Hispanic White individuals, 47.8% [95% CI, 45.9%-49.7%]) compared with individuals of other races and ethnicities. The prevalence of self-reported or parent-reported food allergies was lowest within households earning more than $150 000 per year (8.3% [95% CI, 7.4%-9.2%]).Conclusions and relevance

This survey study of a US nationally representative sample suggests that the prevalence of food allergies was highest among Asian, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Black individuals compared with non-Hispanic White individuals in the US. Further assessment of socioeconomic factors and corresponding environmental exposures may better explain the causes of food allergy and inform targeted management and interventions to reduce the burden of food allergies and disparities in outcomes.Free full text

Racial, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Differences in Food Allergies in the US

Key Points

Question

What is the national distribution of food allergies among all US individuals across race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic groups?

Findings

In this survey study of 51 819 households, Asian, Black, and Hispanic individuals were more likely to report having food allergies compared with White individuals. The prevalence of food allergies was lowest among households in the highest income bracket.

819 households, Asian, Black, and Hispanic individuals were more likely to report having food allergies compared with White individuals. The prevalence of food allergies was lowest among households in the highest income bracket.

Meaning

This study suggests that racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic differences in the prevalence of food allergies exist and are evident in clinical outcomes such as food allergy–related emergency department visits and epinephrine autoinjector use.

Abstract

Importance

Food allergies affect approximately 8% of children and 11% of adults in the US. Racial differences in food allergy outcomes have previously been explored among Black and White children, but little is known about the distribution of food allergies across other racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic subpopulations.

Objective

To estimate the national distribution of food allergies across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups in the US.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cross-sectional survey study, conducted from October 9, 2015, to September 18, 2016, a population-based survey was administered online and via telephone. A US nationally representative sample was surveyed. Participants were recruited using both probability- and nonprobability-based survey panels. Statistical analysis was performed from September 1, 2022, through April 10, 2023.

Exposures

Demographic and food allergy–related participant characteristics.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Stringent symptom criteria were developed to distinguish respondents with a “convincing” food allergy from those with similar symptom presentations (ie, food intolerance or oral allergy syndrome), with or without physician diagnosis. The prevalence of food allergies and their clinical outcomes, such as emergency department visits, epinephrine autoinjector use, and severe reactions, were measured across race (Asian, Black, White, and >1 race or other race), ethnicity (Hispanic and non-Hispanic), and household income. Complex survey-weighted proportions were used to estimate prevalence rates.

Results

The survey was administered to 51 819 households comprising 78

819 households comprising 78 851 individuals (40

851 individuals (40 443 adults and parents of 38

443 adults and parents of 38 408 children; 51.1% women [95% CI, 50.5%-51.6%]; mean [SD] age of adults, 46.8 [24.0] years; mean [SD] age of children, 8.7 [5.2] years): 3.7% Asian individuals, 12.0% Black individuals, 17.4% Hispanic individuals, 62.2% White individuals, and 4.7% individuals of more than 1 race or other race. Non-Hispanic White individuals across all ages had the lowest rate of self-reported or parent-reported food allergies (9.5% [95% CI, 9.2%-9.9%]) compared with Asian (10.5% [95% CI, 9.1%-12.0%]), Hispanic (10.6% [95% CI, 9.7%-11.5%]), and non-Hispanic Black (10.6% [95% CI, 9.8%-11.5%]) individuals. The prevalence of common food allergens varied by race and ethnicity. Non-Hispanic Black individuals were most likely to report allergies to multiple foods (50.6% [95% CI, 46.1%-55.1%]). Asian and non-Hispanic White individuals had the lowest rates of severe food allergy reactions (Asian individuals, 46.9% [95% CI, 39.8%-54.1%] and non-Hispanic White individuals, 47.8% [95% CI, 45.9%-49.7%]) compared with individuals of other races and ethnicities. The prevalence of self-reported or parent-reported food allergies was lowest within households earning more than $150

408 children; 51.1% women [95% CI, 50.5%-51.6%]; mean [SD] age of adults, 46.8 [24.0] years; mean [SD] age of children, 8.7 [5.2] years): 3.7% Asian individuals, 12.0% Black individuals, 17.4% Hispanic individuals, 62.2% White individuals, and 4.7% individuals of more than 1 race or other race. Non-Hispanic White individuals across all ages had the lowest rate of self-reported or parent-reported food allergies (9.5% [95% CI, 9.2%-9.9%]) compared with Asian (10.5% [95% CI, 9.1%-12.0%]), Hispanic (10.6% [95% CI, 9.7%-11.5%]), and non-Hispanic Black (10.6% [95% CI, 9.8%-11.5%]) individuals. The prevalence of common food allergens varied by race and ethnicity. Non-Hispanic Black individuals were most likely to report allergies to multiple foods (50.6% [95% CI, 46.1%-55.1%]). Asian and non-Hispanic White individuals had the lowest rates of severe food allergy reactions (Asian individuals, 46.9% [95% CI, 39.8%-54.1%] and non-Hispanic White individuals, 47.8% [95% CI, 45.9%-49.7%]) compared with individuals of other races and ethnicities. The prevalence of self-reported or parent-reported food allergies was lowest within households earning more than $150 000 per year (8.3% [95% CI, 7.4%-9.2%]).

000 per year (8.3% [95% CI, 7.4%-9.2%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

This survey study of a US nationally representative sample suggests that the prevalence of food allergies was highest among Asian, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Black individuals compared with non-Hispanic White individuals in the US. Further assessment of socioeconomic factors and corresponding environmental exposures may better explain the causes of food allergy and inform targeted management and interventions to reduce the burden of food allergies and disparities in outcomes.

Introduction

Food allergies (FAs) affect an estimated 8% of children and 11% of adults in the US.1,2 Individuals with an FA may experience FA-related economic burden, lower health-related quality of life, and increased risk of comorbid atopic conditions (ie, eczema, asthma, and/or allergic rhinitis).3 However, the distribution of FA burden may vary across different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic strata.4,5

The prevalence of self-reported FAs has been increasing in recent decades, especially among non-Hispanic Black (hereafter, Black) children.6 Black children have been reported to have higher rates of FAs compared with non-Hispanic White (hereafter, White) children in the US.7,8 In the 2007-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 8.1% of Black children had parent-reported FAs compared with 6.3% of White children and 5.2% of Hispanic children.9 Black children also often had higher food-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels.10,11,12 In a Boston-area birth cohort study, Black children were reported to be more likely to be sensitized to any food allergens and multiple food allergens compared with White children.13 Less is known about racial differences in FAs among adults, although the limited available evidence suggests that the differences reported in pediatric samples may also exist among adults.14 The NHANES sensitization data from 2005-2006 suggested that serologically defined FA to peanut, egg white, cow’s milk, and shrimp was more common among Black children and adults.12 These study findings and others, compiled using medical record review and random digit dial survey methods, concluded that Black children and adults have higher rates of seafood allergy compared with other races and ethnicities.4,15,16

Despite a growing body of literature on racial differences in FA prevalence and phenotypes between Black and White populations, there remains a paucity of population-based data on FA burden among other races and ethnicities in the US across all age groups—particularly within the past decade. In addition, although a complex interplay between race and socioeconomic factors exists, these social determinants of health remain underexplored in FA research, to our knowledge.5 Therefore, this study aimed to estimate the distribution of self-reported or parent-reported, “convincing” FAs, reaction severity, and management among individuals of varying racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds in the US.

Methods

Between October 9, 2015, and September 18, 2016, a population-based survey was developed and administered to 51 819 US households, obtaining parent-reported responses for 38

819 US households, obtaining parent-reported responses for 38 408 children (≤18 years) and self-reported responses from 40

408 children (≤18 years) and self-reported responses from 40 443 adults (>18 years). Adults completed the survey in English or Spanish via telephone or online. The probability-based sampling methods used included additional coverage of rural and low-income households that are frequently underrepresented in surveys relying on address-based or convenience sampling.1,2 The institutional review boards of Northwestern University and NORC (National Opinion Research Center) at the University of Chicago approved all research study activities. Written and oral informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study followed the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) reporting guidelines.

443 adults (>18 years). Adults completed the survey in English or Spanish via telephone or online. The probability-based sampling methods used included additional coverage of rural and low-income households that are frequently underrepresented in surveys relying on address-based or convenience sampling.1,2 The institutional review boards of Northwestern University and NORC (National Opinion Research Center) at the University of Chicago approved all research study activities. Written and oral informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study followed the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) reporting guidelines.

Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measures included overall pediatric and adult self-reported prevalence of any FA(s) to 9 common, federally regulated food allergens (cow’s milk, hen’s egg, peanut, tree nuts, soy, wheat, sesame, fin fish, and shellfish) among various racial and ethnic groups. Data on physician-diagnosed comorbid atopic conditions, allergic reaction symptoms, severe FAs, emergency department (ED) visits, epinephrine prescriptions, and presence of multiple FAs were also obtained.

Self-reported or parent-reported FA prevalence was calculated for physician-confirmed FAs and “convincing” FAs (self-reported or parent-reported FAs corroborated by a history of symptoms related to an IgE-mediated FA). Self-reported or parent-reported convincing FAs were identified using a stringent algorithm that incorporated a stringent IgE-mediated FA symptom list and reported food allergens. The algorithm was designed to exclude reported FA cases that did not have a clinical food-specific reaction history indicative of a true IgE-mediated FA, such as suspected food intolerances and oral allergy syndrome.1,2 “Physician-confirmed FAs” (hereafter, confirmed FAs) met the criteria for convincing FAs but were also reported as physician diagnosed via confirmatory oral food challenge, skin prick, and/or specific IgE testing. Food allergies were considered severe if stringently defined symptoms were reported that involved 2 or more organ systems as defined: (1) skin and/or oral mucosa system: hives, swelling, lip and/or tongue swelling, difficulty swallowing, or throat tightening; (2) respiratory system: chest tightening, trouble breathing, or wheezing; (3) gastrointestinal system: vomiting; and (4) cardiovascular and/or heart system: chest pain, rapid heart rate, fainting, dizziness, feeling lightheaded, or low blood pressure.1,2

Assessment of Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status

Race is a sociopolitically constructed categorization based on phenotypic indicators. Ethnicity is also a distinct social construct that refers to a shared cultural origin.17 US Census definitions were used for race (ie, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White, >1 race, or other) and ethnicity (ie, Hispanic or Latino and not Hispanic or Latino).18 Due to sample size limitations, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, and those who reported more than 1 race or other race were collapsed into a “more than 1 or other race” category. Therefore, presented estimates are stratified across the following 5 racial and ethnic categories: Asian, Black, Hispanic, White, and more than 1 or other race.

The socioeconomic factors assessed by the survey included household income (<$25 000, $25

000, $25 000-$49

000-$49 999, $50

999, $50 000-$99

000-$99 999, $100

999, $100 000-$149

000-$149 999, or ≥$150

999, or ≥$150 000) and insurance type (uninsured, private insurance, or public insurance), all of which were self-reported. Insurance status was available only for a subset of 6761 AmeriSpeak panelists.

000) and insurance type (uninsured, private insurance, or public insurance), all of which were self-reported. Insurance status was available only for a subset of 6761 AmeriSpeak panelists.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed from September 1, 2022, through April 10, 2023. Self-reported confirmed and convincing FA prevalence estimates were calculated using complex survey weighted proportions.1,2 Pearson χ2 statistics were calculated to test the independence of key study variables. Covariate-adjusted, complex survey-weighted logistic regression models compared relative prevalence and other convincing FA outcomes by participant characteristics, including interaction terms to assess moderation effects by demographic information. Two-sided hypothesis tests were used, and conventional thresholds of P <

< .05 denoted statistical significance. Stata MP, version 16 (StataCorp LLC), was used for all analyses.

.05 denoted statistical significance. Stata MP, version 16 (StataCorp LLC), was used for all analyses.

Results

Demographic Characteristics and Convincing FA Prevalence

Surveys were completed for 78 851 individuals (self-reported for 40

851 individuals (self-reported for 40 443 adults and parents or proxies for 38

443 adults and parents or proxies for 38 408 children; 51.1% women [95% CI, 50.5%-51.6%]; mean [SD] age of adults, 46.8 [24.0] years; mean [SD] age of children, 8.7 [5.2] years). Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of all respondents and those with convincing FA, separately. The sample comprised 3.7% Asian individuals, 12.0% Black individuals, 17.4% Hispanic individuals, 62.2% White individuals, and 4.7% individuals of more than 1 race or other race. Observed weighted distributions by age, sex, race, and ethnicity were comparable to the general US population.18

408 children; 51.1% women [95% CI, 50.5%-51.6%]; mean [SD] age of adults, 46.8 [24.0] years; mean [SD] age of children, 8.7 [5.2] years). Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of all respondents and those with convincing FA, separately. The sample comprised 3.7% Asian individuals, 12.0% Black individuals, 17.4% Hispanic individuals, 62.2% White individuals, and 4.7% individuals of more than 1 race or other race. Observed weighted distributions by age, sex, race, and ethnicity were comparable to the general US population.18

Table 1.

| Characteristic | All US children and adults (n = = 78 78 851) 851) | Children and adults with convincing FA (n = = 9726) 9726) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 3119b | 3.7 (3.5-4.0)b | 410b | 3.9 (3.4-4.4)b |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 7687b | 12 (11.6-12.5)b | 1024b | 12.7 (11.6-13.9)b |

| Hispanic | 8636b | 17.4 (16.7-18.1)b | 1368b | 18.3 (16.9-19.7)b |

| White, non-Hispanic | 54 990 990 | 62.2 (61.4-62.9) | 6326 | 58.9 (57.3-60.6) |

| Multiple or otherc | 4439b | 4.7 (4.4-4.9)b | 598b | 6.2 (5.4-7.2)b |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 41 29 b 29 b | 51.1 (50.5-51.6)b | 5439b | 63.3 (61.9-64.8)b |

| Male | 37 573b 573b | 48.9 (48.4-49.5)b | 4287b | 36.7 (35.2-38.1)b |

| Age, y | ||||

| <1 | 1851b | 1.2 (1.1-1.3)b | 92b | 0.3 (0.3-0.4)b |

| 1 | 1817b | 1.1 (1.0-1.2)b | 166b | 1.0 (0.7-1.3)b |

| 2 | 2102b | 1.3 (1.2-1.4)b | 194b | 1.3 (0.9-1.8)b |

| 3-5 | 6164b | 3.6 (3.5-3.8)b | 550b | 3.0 (2.6-3.6)b |

| 6-10 | 10 524b 524b | 6.2 (6.0-6.5)b | 967b | 5.0 (4.4-5.5)b |

| 11-13 | 6663b | 3.7 (3.5-3.9)b | 631b | 2.8 (2.4-3.3)b |

| 14-17 | 9295b | 5.2 (5.0-5.5)b | 832b | 3.7 (3.3-4.1)b |

| 18-29 | 8336b | 16.7 (16.2-17.2)b | 1593b | 18.7 (17.5-20.0)b |

| 30-39 | 7803b | 13.2 (12.8-13.5)b | 1446b | 16.6 (15.5-17.8)b |

| 40-49 | 6289b | 13.0 (12.6-13.4)b | 1002b | 13.0 (12.0-14.1)b |

| 50-59 | 7799b | 14.0 (13.6-14.4)b | 1062b | 16.5 (15.4-17.8)b |

| ≥60 | 10 218b 218b | 20.8 (20.3-21.3)b | 1189b | 18.1 (16.9-19.4)b |

| Annual household income, $ | ||||

<25 000 000 | 12 943b 943b | 16.5 (16.0-17.0)b | 1554b | 16.2 (15.1-17.4)b |

25 000-49 000-49 999 999 | 19 653b 653b | 22.0 (21.4-22.6)b | 2465b | 22.4 (21.2-23.7)b |

50 000-99 000-99 999 999 | 28 537b 537b | 31.0 (30.3-31.7)b | 3651b | 33.0 (31.6-34.6)b |

100 000-149 000-149 999 999 | 11 635b 635b | 19.5 (18.9-20.2)b | 1374b | 19.3 (17.9-20.8)b |

≥150 000 000 | 6103b | 11.0 (10.5-11.6)b | 682b | 9.0 (8.1-10.1)b |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Uninsured | 525 | 8.0 (6.7-9.6) | 56 | 8.4 (5.8-12.0) |

| Private insurance | 4310 | 66.3 (64.1-68.5) | 429 | 63.0 (57.9-67.9) |

| Public insurance | 1926 | 25.6 (23.8-27.6) | 219 | 28.6 (24.2-33.4) |

| Geographic region | ||||

| West | 16 872 872 | 23.8 (23.1-24.5) | 2227 | 24.7 (23.3-26.1) |

| Midwest | 17 983 983 | 20.9 (20.3-21.4) | 2015 | 19.9 (18.7-21.1) |

| South | 29 292 292 | 37.7 (36.9-38.4) | 3620 | 36.8 (35.3-38.4) |

| Northeast | 14 328 328 | 17.7 (17.1-18.3) | 1827 | 18.7 (17.3-20.1) |

| Physician-diagnosed comorbid conditions | ||||

| Asthma | 9510b | 12.2 (11.8-12.7)b | 2549b | 25.3 (23.9-26.7)b |

| Atopic dermatitis or eczema | 4718b | 6.5 (6.2-6.9)b | 1156b | 12.5 (11.5-13.6)b |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | 163b | 0.2 (0.1-0.2)b | 74b | 0.6 (0.5-0.9)b |

| Food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome | 374b | 0.3 (0.2-0.3)b | 240b | 1.5 (1.2-1.8)b |

| Allergic rhinitis | 14 164b 164b | 19.5 (19.0-20.0)b | 3094b | 33.6 (32.2-35.2)b |

| Insect sting allergy | 2443b | 3.5 (3.3-3.7)b | 739b | 7.8 (7.1-8.7)b |

| Latex allergy | 1534b | 2.0 (1.9-2.2)b | 593b | 6.2 (5.5-7.0)b |

| Medication allergy | 7269b | 11.3 (11.0-11.7)b | 1699b | 20.8 (19.6-22.2)b |

| Urticaria or chronic hives | 587b | 0.8 (0.7-0.9)b | 215b | 2.2 (1.8-2.6)b |

| Other chronic condition | 4285b | 6.4 (6.1-6.7)b | 755b | 8.4 (7.6-9.3)b |

Abbreviation: FA, food allergy.

<

< .05.

.05.An estimated 5.0% of individuals in the US, across all age groups, have a physician-confirmed FA, while 10.1% have a convincing FA. By observing confirmed and convincing FA rates by age, this study found that FA rates increased during pediatric ages, plateaued during adulthood, and decreased during geriatric years among all race and ethnicity categories (eFigure in Supplement 1).

By comparing rates of convincing FAs by race and ethnicity, this study found that 10.5% (95% CI, 9.1%-12.0%) of Asian individuals, 10.6% (95% CI, 9.8%-11.5%) of Black individuals, 10.6% (95% CI, 9.7%-11.5%) of Hispanic individuals, and 9.5% of (95% CI, 9.2%-9.9%) White individuals had a convincing FA (Table 2). Black children had the highest rate of convincing FAs (8.9% [95% CI, 7.6%-10.3%]), and Asian children had the lowest rate at 6.5% (95% CI, 5.1%-8.2%) (Table 3). Black children had the highest rate of convincing peanut allergy (3.0% [95% CI, 2.4%-3.8%]) compared with all other race and ethnicity categories. Asian children reported higher rates of tree nut allergy compared with children from other racial and ethnic groups (2.0% [95% CI, 1.2%-3.2%]). Black children reported the highest rate of egg allergy (1.6% [95% CI, 1.0%-2.7%]) and fin fish allergy (0.9% [95% CI, 0.6%-1.5%]). Among the adult population, White adults had the lowest rate of convincing FAs (10.1% [95% CI, 9.7%-10.6%]) compared with other races and ethnicities, which were comparable in rates. The prevalence of peanut allergy (2.9% [95% CI, 2.0%-4.2%]) and the prevalence of shellfish allergy (3.8% [95% CI, 3.0%-4.9%]) were highest among Asian adults. Tree nut allergy prevalence was highest among Black adults (1.6% [95% CI, 1.2%-2.1%]). Hen’s egg allergy prevalence (1.2% [95% CI, 0.8%-1.8%]) and fin fish allergy prevalence (1.5% [95% CI, 1.1%-1.9%]) were highest among Hispanic adults.

Table 2.

| Characteristic | All | Peanut | Milk | Shellfish | Tree nut | Egg | Fin fish | Wheat | Soy | Sesame | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Asian | 410 | 10.5 (9.1-12.0) | 122 | 2.9 (2.1-3.9) | 76 | 1.5 (1.1-2.0) | 129 | 3.4 (2.7-4.3) | 58 | 1.3 (0.9-1.8) | 52 | 1.1 (0.8-1.6) | 37 | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 13 | 0.4 (0.2-0.7) | 28 | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 7 | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) |

| Black | 1024 | 10.6 (9.8-11.5) | 282 | 2.5 (2.1-3.0) | 212 | 2.3 (1.9-2.8) | 303 | 3.0 (2.6-3.0) | 166 | 1.6 (1.3-2.0) | 116 | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) | 95 | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 51 | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 60 | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) | 30 | 0.2 (0.2-0.4) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1368 | 10.6 (9.7-11.5) | 398 | 2.4 (2.1-2.8) | 289 | 2.5 (2.0-3.0) | 366 | 2.8 (2.4-3.3) | 209 | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | 135 | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 139 | 1.2 (1.0-1.6) | 84 | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 97 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 46 | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) |

| White | 6326 | 9.5 (9.2-9.9) | 1357 | 1.6 (1.4-1.7) | 1243 | 1.6 (1.5-1.8) | 1406 | 2.3 (2.1-2.5) | 825 | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 545 | 0.6 (0.6-0.7) | 477 | 0.7 (0.6-0.7) | 459 | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 361 | 0.5 (0.4-0.6) | 159 | 0.2 (0.2-0.3) |

| Multiple or otherb | 598 | 13.4 (11.8-15.3) | 126 | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) | 142 | 3.0 (2.2-4.2) | 127 | 3.3 (2.4-4.4) | 73 | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 60 | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 40 | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | 39 | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 34 | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | 9 | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) |

| χ2 Value | 7.8 | 85.5 | 79.4 | 41.3 | 26.2 | 53 | 49.1 | 16 | 21 | 8.1 | ||||||||||

| P valuec | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .001 | .002 | <.001 | <.001 | <.05 | .01 | .17 | ||||||||||

| Household income, $ | ||||||||||||||||||||

<25 000 000 | 1554 | 9.9 (9.2-10.6) | 275 | 1.5 (1.2-1.7) | 326 | 1.9 (1.7-2.3) | 395 | 2.6 (2.2-3.0) | 177 | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | 133 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 164 | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | 97 | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 106 | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) | 26 | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) |

25 000 to 49 000 to 49 999 999 | 2465 | 10.3 (9.7-10.8) | 511 | 1.7 (1.5-1.9) | 499 | 2.0 (1.8-2.3) | 555 | 2.4 (2.1-2.7) | 318 | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | 208 | 0.8 (0.6-0.9) | 176 | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | 153 | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 141 | 0.7 (0.5-0.8) | 49 | 0.2 (0.2-0.3) |

50 000 to 99 000 to 99 999 999 | 3651 | 10.7 (10.2-11.3) | 944 | 2.2 (2.0-2.4) | 781 | 2.1 (1.9-2.4) | 910 | 2.8 (2.5-3.1) | 507 | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | 365 | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 291 | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 248 | 0.8 (0.6-0.9) | 219 | 0.6 (0.5-0.8) | 115 | 0.3 (0.2-0.3) |

100 000 to 149 000 to 149 999 999 | 1374 | 10.0 (9.2-10.8) | 383 | 2.2 (1.9-2.6) | 239 | 1.7 (1.3-2.1) | 311 | 2.6 (2.2-3.0) | 215 | 1.3 (1.0-1.5) | 149 | 0.9 (0.7-1.3) | 103 | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 100 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 74 | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 39 | 0.3 (0.2-0.4) |

≥150 000 000 | 682 | 8.3 (7.4-9.2) | 172 | 1.6 (1.3-2.0) | 117 | 1.6 (1.2-2.2) | 160 | 2.0 (1.6-2.5) | 114 | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | 53 | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 54 | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 48 | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 40 | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 22 | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) |

| χ2 Value | 5.1 | 38.4 | 14.6 | 17.3 | 5.7 | 26.9 | 25.8 | 5.4 | 23.8 | 5.7 | ||||||||||

| P valuec | <.001 | <.001 | .22 | .09 | .44 | .01 | .004 | .63 | .008 | .41 | ||||||||||

| Insurance status | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Uninsured | 56 | 10.3 (7.4-14.3) | 4 | 0.3 (0.1-1.0) | 14 | 2.0 (1.1-3.8) | 14 | 2.4 (1.3-4.7) | 6 | 0.6 (0.3-1.6) | 2 | 0.8 (0.2-3.4) | 5 | 1.5 (0.5-4.0) | 1 | 0.1 (0.0-0.6) | 4 | 0.7 (0.2-2.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Private insurance | 429 | 9.4 (8.3-10.5) | 62 | 1.2 (0.9-1.7) | 81 | 2.0 (1.4-2.6) | 93 | 2.2 (1.7-2.9) | 55 | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 26 | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 18 | 0.4 (0.2-0.6) | 38 | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 23 | 0.5 (0.3-0.9) | 6 | 0.2 (0.1-0.5) |

| Public insurance | 219 | 11.0 (9.3-12.9) | 13 | 0.8 (0.4-1.7) | 45 | 2.2 (1.5-3.2) | 51 | 2.6 (1.9-3.7) | 16 | 0.7 (0.3-1.5) | 12 | 0.7 (0.3-1.4) | 19 | 0.9 (0.5-1.4) | 18 | 0.9 (0.4-1.8) | 8 | 0.5 (0.2-1.0) | 3 | 0.1 (0.0-0.3) |

| χ2 Value | 1.2 | 5.7 | 0.45 | 0.7 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 1.37 | 4.2 | 0.6 | 1.6 | ||||||||||

| P valuec | .32 | .13 | .85 | .78 | .28 | .52 | .01 | .18 | .83 | .52 | ||||||||||

<

< .05.

.05.Table 3.

| Characteristic | All | Peanut | Milk | Shellfish | Tree nut | Egg | Fin fish | Wheat | Soy | Sesame | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | |

| Race and ethnicity in pediatric population only | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Asian | 116 | 6.5 (5.1-8.2) | 47 | 2.6 (1.8-3.8) | 28 | 1.6 (1.0-2.7) | 30 | 1.7 (1.1-2.7) | 26 | 2.0 (1.2-3.2) | 16 | 1.0 (0.5-1.9) | 9 | 0.5 (0.2-1.2) | 3 | 0.3 (0.1-1.4) | 6 | 0.4 (0.1-1.3) | 3 | 0.3 (0.1-1.4) |

| Black | 261 | 8.9 (7.6-10.3) | 138 | 3.0 (2.4-3.8) | 75 | 2.2 (1.5-3.3) | 98 | 2.2 (1.7-2.9) | 73 | 1.6 (1.1-2.2) | 55 | 1.6 (1.0-2.7) | 40 | 0.9 (0.6-1.5) | 18 | 0.4 (0.2-0.7) | 22 | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | 14 | 0.3 (0.2-0.6) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 493 | 8.4 (7.2-9.8) | 168 | 2.5 (1.9-3.2) | 116 | 2.2 (1.5-3.1) | 92 | 1.5 (0.8-2.0) | 89 | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) | 55 | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | 30 | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | 24 | 0.4 (0.3-0.7) | 30 | 0.5 (0.3-0.8) | 17 | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) |

| White | 2186 | 7.0 (6.4-7.6) | 662 | 1.8 (1.6-2.1) | 547 | 1.8 (1.6-2.1) | 329 | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 352 | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 252 | 0.7 (0.7-0.9) | 141 | 0.4 (0.3-0.5) | 140 | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 133 | 0.4 (0.3-0.7) | 64 | 0.2 (0.1-0.2) |

| Multiple or otherb | 276 | 8.1 (6.7-9.8) | 86 | 2.5 (1.8-3.6) | 71 | 1.7 (1.3-2.3) | 50 | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 47 | 1.3 (0.9-2.1) | 40 | 1.3 (0.8-2.3) | 17 | 0.4 (0.2-0.6) | 20 | 0.5 (0.3-0.8) | 13 | 0.4 (0.2-0.8) | 4 | 0.1 (0.0-0.2) |

| χ2 Value | 3.2 | 65.3 | 14.7 | 114.1 | 42.5 | 87.1 | 67.7 | 9.6 | 4.5 | 22.8 | ||||||||||

| P valuec | .02 | .01 | .64 | <.001 | .03 | .007 | .008 | .67 | .91 | .16 | ||||||||||

| Annual household income in pediatric population only, $ | ||||||||||||||||||||

<25 000 000 | 380 | 7.3 (6.1-8.6) | 104 | 1.7 (1.3-2.3) | 99 | 1.8 (1.2-2.7) | 66 | 1.3 (0.8-2.0) | 51 | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) | 45 | 0.7 (0.4-1.3) | 38 | 1.0 (0.6-1.8) | 15 | 0.3 (0.1-0.6) | 28 | 0.6 (0.3-1.3) | 7 | 0.1 (0.0-0.4) |

25 000 to 49 000 to 49 999 999 | 771 | 8.0 (7.1-9.0) | 210 | 1.8 (1.5-2.3) | 195 | 2.2 (1.7-2.8) | 104 | 1.1 (0.9-1.5) | 114 | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | 82 | 0.8 (0.6-1.2) | 41 | 0.4 (0.3-0.7) | 43 | 0.6 (0.3-1.0) | 50 | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 19 | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) |

50 000 to 99 000 to 99 999 999 | 1408 | 7.7 (7.0-8.4) | 464 | 2.3 (2.0-2.7) | 365 | 2.1 (1.7-2.6) | 275 | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | 247 | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 174 | 1.1 (0.8-1.6) | 102 | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 92 | 0.5 (0.4-0.8) | 79 | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 49 | 0.2 (0.2-0.4) |

100 000 to 149 000 to 149 999 999 | 582 | 8.1 (6.8-9.6) | 217 | 2.7 (2.1-3.6) | 127 | 2.0 (1.3-3.1) | 94 | 1.1 (0.8-1.4) | 110 | 1.4 (1.1-1.8) | 86 | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | 32 | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) | 36 | 0.6 (0.3-1.0) | 30 | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) | 15 | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) |

≥150 000 000 | 291 | 6.4 (5.2-7.9) | 106 | 2.5 (1.7-3.8) | 51 | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 60 | 1.6 (0.9-2.6) | 65 | 1.2 (0.9-1.7) | 31 | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 24 | 0.4 (0.3-0.7) | 19 | 0.5 (0.3-0.9) | 17 | 0.3 (0.2-0.6) | 12 | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) |

| χ2 Value | 1 | 48.9 | 59.3 | 16.3 | 17.5 | 33.2 | 72.6 | 16.8 | 32.6 | 4.6 | ||||||||||

| P valuec | .38 | .10 | .13 | .56 | .36 | .26 | .006 | .58 | .24 | .84 | ||||||||||

| Insurance in pediatric population only | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Uninsured | 11 | 4.9 (2.3-9.8) | 1 | 0.4 (0.1-2.7) | 5 | 2.3 (0.8-6.7) | 1 | 0.4 (0.1-2.7) | 1 | 0.3 (0.0-2.1) | 1 | 0.6 (0.1-3.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.2 (0.0-1.5) | 1 | 0.3 (0.0-1.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Private insurance | 104 | 5.7 (4.4-7.4) | 29 | 1.5 (0.9-2.6) | 26 | 1.6 (0.9-3.0) | 9 | 0.4 (0.2-0.8) | 20 | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | 10 | 0.4 (0.2-0.9) | 6 | 0.3 (0.1-0.7) | 13 | 0.8 (0.5-1.5) | 5 | 0.4 (0.1-1.0) | 2 | 0.1 (0.0-0.4) |

| Public insurance | 35 | 7.0 (4.7-10.5) | 3 | 0.2 (0.1-0.9) | 12 | 3.2 (1.6-6.4) | 7 | 1.1 (0.5-2.6) | 2 | 0.2 (0.0-0.8) | 3 | 1.3 (0.4-1.2) | 1 | 0.1 (0.0-0.5) | 2 | 0.3 (0.1-1.2) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.3 (0.1-1.2) |

| χ2 Value | 0.53 | 26.8 | 20.3 | 13.9 | 12.8 | 18 | 5.1 | 10.6 | 7.4 | 4.1 | ||||||||||

| P valuec | .59 | .01 | .27 | .15 | .08 | .26 | .39 | .14 | .42 | .56 | ||||||||||

| Race and ethnicity in adult population only | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Asian | 294 | 11.4 (9.8-13.3) | 75 | 2.9 (2.0-4.2) | 48 | 1.5 (1.0-2.0) | 99 | 3.8 (3.0-4.9) | 32 | 1.1 (0.8-1.7) | 36 | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) | 28 | 1.0 (0.6-1.5) | 10 | 0.4 (0.2-0.7) | 22 | 0.7 (0.5-1.2) | 4 | 0.2 (0.1-0.5) |

| Black | 663 | 11.2 (10.2-12.3) | 144 | 2.4 (1.9-2.9) | 137 | 2.3 (1.9-2.9) | 205 | 3.3 (2.8-3.9) | 93 | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) | 61 | 1.0 (0.7-1.5) | 55 | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | 33 | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | 38 | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) | 16 | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 875 | 11.6 (10.5-12.8) | 230 | 2.4 (2.0-2.9) | 173 | 2.6 (2.1-3.3) | 274 | 3.4 (2.8-4.0) | 120 | 1.5 (1.1-1.9) | 80 | 1.2 (0.8-1.8) | 109 | 1.5 (1.1-1.9) | 60 | 0.8 (0.5-1.1) | 67 | 1.0 (0.7-1.3) | 29 | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) |

| White | 4140 | 10.1 (9.7-10.6) | 695 | 1.5 (1.4-1.7) | 696 | 1.6 (1.5-1.8) | 1077 | 2.6 (2.4-2.8) | 473 | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 293 | 0.6 (0.5-0.7) | 336 | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | 319 | 0.9 (0.7-1.0) | 228 | 0.5 (0.5-0.6) | 95 | 0.2 (0.2-0.3) |

| Multiple or otherb | 322 | 15.9 (13.6-18.6) | 40 | 1.2 (0.8-1.7) | 71 | 3.7 (2.5-5.4) | 77 | 4.3 (3.1-6.0) | 26 | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | 20 | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | 23 | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) | 19 | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 21 | 1.0 (0.5-1.7) | 5 | 0.2 (0.1-0.5) |

| χ2 Value | 9.6 | 96.9 | 127.5 | 62.4 | 28.4 | 59.1 | 64.8 | 15.6 | 39 | 7.7 | ||||||||||

| P valuec | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .01 | .001 | <.001 | .15 | .002 | .35 | ||||||||||

| Annual household income in adult population only, $ | ||||||||||||||||||||

<25 000 000 | 1174 | 10.6 (9.8-11.5) | 171 | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) | 227 | 2.0 (1.6-2.4) | 329 | 3.0 (2.5-3.5) | 126 | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | 88 | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | 126 | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) | 82 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 78 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 19 | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) |

25 000 to 49 000 to 49 999 999 | 1694 | 10.9 (10.2-11.6) | 301 | 1.6 (1.4-1.9) | 304 | 1.9 (1.7-2.2) | 451 | 2.8 (2.4-3.2) | 204 | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 126 | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) | 135 | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) | 110 | 0.7 (0.6-1.0) | 91 | 0.6 (0.5-0.9) | 30 | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) |

50 000 to 99 000 to 99 999 999 | 2243 | 11.6 (9.6-12.3) | 480 | 2.1 (1.9-2.4) | 416 | 2.1 (1.9-2.4) | 635 | 3.2 (2.9-3.6) | 260 | 1.2 (1.1-1.5) | 191 | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 189 | 0.9 (0.7-1.0) | 156 | 0.8 (0.7-1.1) | 140 | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | 66 | 0.3 (0.2-0.4) |

100 000 to 149 000 to 149 999 999 | 792 | 10.5 (9.6-11.5) | 166 | 2.0 (1.7-2.5) | 112 | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) | 217 | 3.0 (2.5-3.6) | 105 | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 63 | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 71 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 64 | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | 44 | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 24 | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) |

≥150 000 000 | 391 | 8.8 (7.7-10.0) | 66 | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) | 66 | 1.8 (1.3-2.5) | 100 | 2.2 (1.7-2.8) | 49 | 0.9 (0.7-1.3) | 22 | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) | 30 | 0.7 (0.4-1.0) | 29 | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 23 | 0.4 (0.2-0.6) | 10 | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) |

| χ2 Value | 4.5 | 46.5 | 13.9 | 26 | 7.2 | 29.2 | 19.4 | 7.2 | 26.9 | 6.9 | ||||||||||

| P valuec | .001 | <.001 | .36 | .07 | .51 | .05 | .08 | .61 | .02 | .50 | ||||||||||

| Insurance in adult population only | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Uninsured | 45 | 13.5 (9.3-19.3) | 3 | 0.3 (0.1-0.9) | 9 | 1.9 (0.9-3.8) | 13 | 3.6 (1.8-7.1) | 5 | 0.8 (0.3-2.3) | 1 | 0.9 (0.1-6.0) | 5 | 2.3 (0.8-6.3) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.0 (0.2-3.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Private insurance | 325 | 11.3 (9.9-12.9) | 33 | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | 55 | 2.1 (1.5-3.0) | 84 | 3.2 (2.5-4.2) | 35 | 1.2 (0.8-1.8) | 16 | 0.4 (0.2-0.7) | 12 | 0.4 (0.2-0.7) | 25 | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) | 18 | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | 4 | 0.2 (0.1-0.8) |

| Public insurance | 184 | 12.4 (10.4-14.8) | 10 | 1.0 (0.4-2.2) | 33 | 1.9 (1.2-2.8) | 44 | 3.2 (2.2-4.5) | 14 | 0.9 (0.4-1.9) | 9 | 0.4 (0.2-0.9) | 18 | 1.2 (0.7-1.9) | 16 | 1.1 (0.5-2.4) | 8 | 0.6 (0.3-1.4) | 1 | 0 (0.0-0.3) |

| χ2 Value | 0.62 | 3.9 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 3 | 34.2 | 6.9 | 1.3 | 5 | ||||||||||

| P valuec | .53 | .38 | .83 | .94 | .55 | .57 | .003 | .37 | .79 | .38 | ||||||||||

<

< .05.

.05.Convincing FA Prevalence by Socioeconomic Factors

Significant differences in the prevalence of any convincing FA were observed by household income. Convincing FA was most prevalent among households earning $50 000 to $99

000 to $99 999 per year (10.7% [95% CI, 10.2%-11.3%]) and lowest among those earning $150

999 per year (10.7% [95% CI, 10.2%-11.3%]) and lowest among those earning $150 000 or more (8.3% [95% CI, 7.4%-9.2%]) (Table 2). No significant differences in the prevalence of convincing FA were observed by insurance type.

000 or more (8.3% [95% CI, 7.4%-9.2%]) (Table 2). No significant differences in the prevalence of convincing FA were observed by insurance type.

Multiple FAs, Severity, and Reaction Management

Among those with FAs, Black individuals had the highest rate of multiple convincing FAs (50.6% [95% CI, 46.1%-55.1%]) compared with other races and ethnicities (Table 4). Among respondents with convincing FAs, a history of at least 1 severe convincing FA reaction was also highest among Black individuals (55.8% [95% CI, 51.7%-59.8%]), followed by Hispanic individuals (51.3% [95% CI, 47.0%-55.5%]). Asian and White individuals had the lowest rates of severe food allergy reactions (Asian individuals, 46.9% [95% CI, 39.8%-54.1%] and White individuals, 47.8% [95% CI, 45.9%-49.7%]) compared with individuals of other races and ethnicities. Hispanic and Black individuals had higher rates of FA-related ED visits in the last year (Hispanic, 15.5% [95% CI, 12.3%-19.5%]; Black, 13.5% [95% CI, 9.7%-18.4%]) as well as in their lifetime (Hispanic, 47.7% [95% CI, 43.5%-52.0%]; Black, 45.4% [95% CI, 40.8%-50.1%]) compared with other races and ethnicities. In addition, rates of epinephrine autoinjector (EAI) use were highest among Black and Hispanic individuals (Asian, 22.6% [95% CI, 17.7%-28.%%]; Black, 23.6% [95% CI, 20.3%-27.2%]; Hispanic, 24.6% [95% CI, 21.7%-27.9%]; White, 20.9% [95% CI, 19.5%-22.4%]; >1 or other race, 19.4% [14.7%-25.3%]), but no significant differences in overall rates of EAI use (P =

= .14), or presence of a current EAI prescription (Asian, 28.0% [95% CI, 22.4%-34.4%]; Black: 26.7% [95% CI, 23.3%-30.5%]; Hispanic: 30.4% [95% CI, 27.1%-34.1%]; White, 26.0% [95% CI, 24.4%-27.6%]; >1 or other race, 23.6% [18.5%-29.7%]; P

.14), or presence of a current EAI prescription (Asian, 28.0% [95% CI, 22.4%-34.4%]; Black: 26.7% [95% CI, 23.3%-30.5%]; Hispanic: 30.4% [95% CI, 27.1%-34.1%]; White, 26.0% [95% CI, 24.4%-27.6%]; >1 or other race, 23.6% [18.5%-29.7%]; P =

= .11) were observed by race and ethnicity.

.11) were observed by race and ethnicity.

Table 4.

| Characteristic | Severe | EAI prescription | ED visit in last year | Lifetime ED visit | Multiple food allergies | EAI use | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | No.a | % (95% CI) | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Asian | 188 | 46.9 (39.8-54.1) | 136 | 28.0 (22.4-34.4) | 52 | 9.9 (7.1-13.8) | 153 | 36.5 (29.7-43.8) | 180 | 37.2 (31.3-43.6) | 101 | 22.6 (17.7-28.5) |

| Black | 557 | 55.8 (51.7-59.8) | 341 | 26.7 (23.3-30.5) | 137 | 13.5 (9.7-18.4) | 472 | 45.4 (40.8-50.1) | 517 | 50.6 (46.1-55.1) | 275 | 23.6 (20.3-27.2) |

| Hispanic | 702 | 51.3 (47.0-55.5) | 519 | 30.4 (27.1-34.1) | 204 | 15.5 (12.3-19.5) | 678 | 47.7 (43.5-52.0) | 662 | 45.4 (41.2-49.6) | 416 | 24.6 (21.7-27.9) |

| White | 2969 | 47.8 (45.9-49.7) | 2048 | 26.0 (24.4-27.6) | 705 | 8.3 (7.5-9.3) | 2445 | 35.6 (33.8-37.4) | 2716 | 43.8 (41.9-45.6) | 1564 | 20.9 (19.5-22.4) |

| Multiple or otherb | 306 | 50.7 (43.4-57.8) | 182 | 23.6 (18.5-29.7) | 72 | 8.4 (5.9-11.9) | 229 | 33.9 (28.1-40.2) | 265 | 39.4 (33.2-46.0) | 132 | 19.4 (14.7-25.3) |

| χ2 Value | 2.8 | 1.9 | 8 | 10.9 | 3.5 | 1.7 | ||||||

| P valuec | .03 | .11 | <.001 | <.001 | .01 | .14 | ||||||

| Annual household income, $ | ||||||||||||

<25 000 000 | 806 | 54.0 (50.3-57.6) | 382 | 20.9 (18.4-23.8) | 205 | 16.2 (12.9-20.0) | 644 | 44.3 (40.6-48.2) | 694 | 43.8 (40.2-47.4) | 323 | 19.3 (16.7-22.3) |

25 000-49 000-49 999 999 | 1205 | 50.0 (47.1-52.9) | 667 | 22.3 (20.1-24.7) | 240 | 8.9 (7.3-10.7) | 990 | 37.7 (34.9-40.5) | 1081 | 44.0 (41.2-46.9) | 528 | 18.1 (16.1-20.2) |

50 000-99 000-99 999 999 | 1774 | 49.3 (46.7-51.8) | 1386 | 29.7 (27.6-32.0) | 481 | 10.5 (8.7-12.6) | 1586 | 40.9 (38.4-43.6) | 1650 | 46.6 (44.0-49.3) | 1060 | 25.2 (23.1-27.3) |

100 000-149 000-149 999 999 | 629 | 47.7 (43.6-51.9) | 526 | 31.0 (27.5-34.8) | 163 | 8.3 (6.3-10.9) | 511 | 35.1 (31.3-39.1) | 604 | 42.4 (38.4-46.5) | 389 | 21.9 (19.1-25.0) |

≥150 000 000 | 308 | 45.9 (40.1-51.9) | 265 | 28.9 (24.5-33.8) | 81 | 7.7 (5.8-10.2) | 246 | 33.6 (28.5-39.1) | 311 | 42.5 (37.2-48.1) | 188 | 24.2 (19.9-29.2) |

| χ2 Value | 1.88 | 9.4 | 7.1 | 4.7 | 1.1 | 5.4 | ||||||

| P valuec | .11 | <.001 | <.001 | .001 | .35 | <.001 | ||||||

| Insurance status | ||||||||||||

| Uninsured | 31 | 54.7 (38.9-69.5) | 7 | 15.2 (6.6-31.1) | 3 | 3.7 (1.1-11.4) | 22 | 39.2 (24.7-55.9) | 23 | 34.5 (22.1-49.4) | 14 | 22. 3 (11.9-38.1) |

| Private insurance | 195 | 47.1 (41.0-53.3) | 89 | 22.2 (17.3-28.0) | 28 | 8.0 (4.9-12.8) | 109 | 26.5 (21.4-32.2) | 189 | 41.2 (35.5-47.2) | 61 | 14.0 (10.3-18.7) |

| Public insurance | 110 | 49.0 (41.0-57.0) | 27 | 7.8 (5.0-12.2) | 28 | 16.7 (9.0-28.8) | 73 | 35.6 (26.5-46.0) | 109 | 50.8 (41.5-60.1) | 28 | 9.5 (6.1-14.4) |

| χ2 Value | 0.4 | 7.2 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.5 | ||||||

| P valuec | .67 | .001 | .04 | .12 | .10 | .08 | ||||||

Abbreviations: EAI, epinephrine autoinjector; ED, emergency department.

<

< .05.

.05.Patient report of a severe FA reaction history was more common among lower earning households, but again this difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, differences in rates of current epinephrine prescriptions were significantly different by household income, with the lowest earning households least likely to report a current EAI prescription. Report of at least 1 FA-related ED visit (in the last year and lifetime) was most frequent among those with a household income less than $25 000 (last year, 16.2% [95% CI, 12.9%-20.0%]; lifetime, 44.3% [95% CI, 40.6%-48.2%]) (Table 4).

000 (last year, 16.2% [95% CI, 12.9%-20.0%]; lifetime, 44.3% [95% CI, 40.6%-48.2%]) (Table 4).

When observing FA severity by insurance type, no significant differences were observed except for the rate of EAI prescription (P <

< .001), which was the highest for those with private insurance (22.2% [95% CI, 17.3%-28.0%]), as well as rates of FA-related ED visits in the past year, which were most common among publicly-insured respondents (16.7% [95% CI, 9.0%-28.8%]) (Table 4).

.001), which was the highest for those with private insurance (22.2% [95% CI, 17.3%-28.0%]), as well as rates of FA-related ED visits in the past year, which were most common among publicly-insured respondents (16.7% [95% CI, 9.0%-28.8%]) (Table 4).

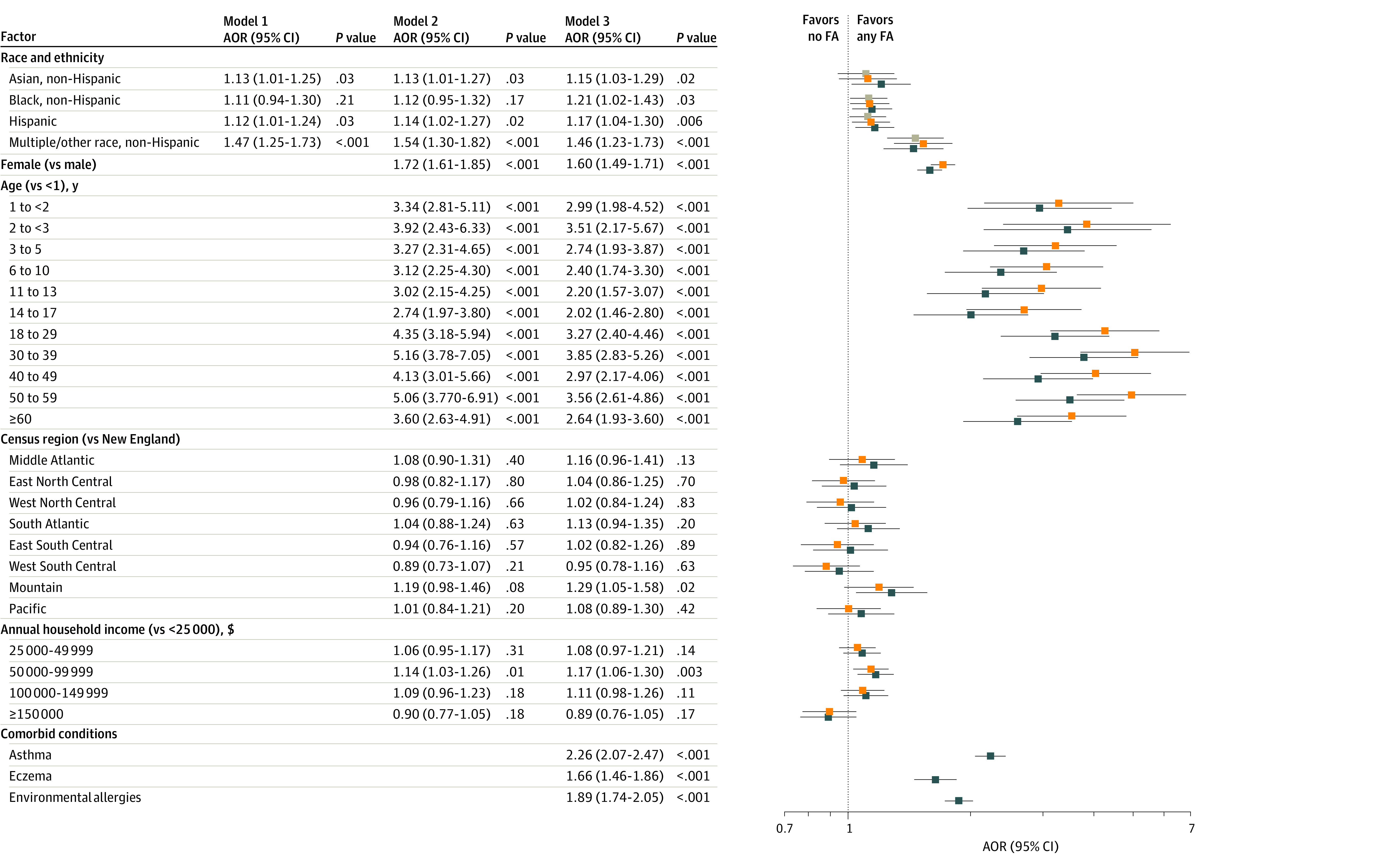

Associations Between Race and Ethnicity With Convincing FA

Odds ratios were generated from a model of logistic regressions adjusted for sex, age, geographic region, household income, and atopic comorbidities. Compared with White individuals, Asian individuals (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.21 [95% CI, 1.02-1.43]; P =

= .03), Black individuals (AOR, 1.15 [95% CI, 1.03-1.29]; P

.03), Black individuals (AOR, 1.15 [95% CI, 1.03-1.29]; P =

= .02), Hispanic individuals (AOR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.04-1.30]; P

.02), Hispanic individuals (AOR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.04-1.30]; P =

= .006), and those categorized as having more than 1 race or other races (AOR, 1.46 [95% CI, 1.23-1.71]; P

.006), and those categorized as having more than 1 race or other races (AOR, 1.46 [95% CI, 1.23-1.71]; P <

< .001) were more likely to have at least 1 convincing FA (Figure).

.001) were more likely to have at least 1 convincing FA (Figure).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the few studies to estimate the prevalence of convincing FAs among children and adults living in the US using a national, probability-based sampling frame and a diverse sample with respect to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. White individuals across all ages had lower rates of convincing FAs (9.5%) compared with Asian, Black, and Hispanic individuals (Asian, 10.5%; Black, 10.6%; Hispanic, 10.6%). Specific food allergen types and rates of FA outcomes (severe allergic reactions, multiple allergies, and ED visits) systematically varied across individuals of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. In addition, a convincing FA and a history of severe FA were seemingly lower among high-income families. This study demonstrates that FA burden disproportionately falls on individuals who report a non-White race and ethnicity19 as well as individuals with lower household incomes.

Asian children reported the highest rates of tree nut allergy, and Black children reported the highest rate of egg allergy and fin fish allergy. In addition, Asian adults reported the highest rate of peanut allergy and shellfish allergy, Black adults reported the highest rate of tree nut allergy, and Hispanic adults reported the highest rate of hen’s egg allergy and fin fish allergy. These findings corroborate existing literature that suggests specific food allergens are more common among different racial and ethnic groups.15 Data collected over a decade ago suggested that Black children and adults exhibited elevated shellfish allergy risk relative to White children and adults.15 More recent literature from the FORWARD study demonstrated that shellfish allergy and fin fish allergy were more common among Black children than White children.20,21 Findings from our study suggest that seafood allergy is also more common among Asian and Hispanic populations. It is unclear what factors are associated with seafood allergy, but previous literature has hypothesized that it may be mediated by differential sensitization to household-level environmental exposures, such as dust mites or cockroaches.22,23 These exposures may be present as a result of environmental injustices latently established through historically racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically biased policies.24 Separately, in an online survey of South Asian Indian individuals living in the US, tree nut allergy was reported to be the most common FA.25 Previous studies from Australia have also demonstrated that tree nut allergies were disproportionately prevalent among children living in Australia who were born to Asian parents.26 Our study sample included Asian individuals from all regions of origin. Considering the heterogeneity within racial and ethnic groups with respect to dietary practices, environmental exposures, and genetic ancestry, as well as the paucity of literature investigating the distribution of FAs among racially and ethnically diverse adult populations, future FA studies should consider further assessment of sociocultural and economic characteristics and explore associations with FA outcomes among individuals of different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Black and Hispanic individuals reported higher rates of severe allergic reactions, allergies to multiple foods, and FA-related ED visits compared with those from other racial and ethnic groups. These national data build on previous published analyses of clinical data from tertiary care medical centers in the Midwestern US, which reported that Black and Hispanic patients with FAs may experience more FA burden compared with patients from other racial or ethnic backgrounds.4 Previous data from Florida demonstrated that Black and Hispanic children had higher rates of food-induced anaphylaxis and ED visits.27 In an observational study of ED data from New York and Florida, ED rates for food-induced anaphylaxis were highest among young Black children living in urban environments.28 In a secondary analysis of the US National Mortality Database from 1999 to 2010, rates of fatal food-induced anaphylaxis significantly increased among African American male patients but not among other demographic groups.14 A better understanding of how socioeconomic factors and barriers are associated with FA outcomes is necessary to develop effective interventions to improve FA management. Considering the disproportionate FA burden among Black and Hispanic individuals in the US, as well as those from households with lower incomes, further research is necessary to explore barriers and facilitators to FA management that are specifically experienced by these individuals and families to allow for the development of more targeted, culturally relevant, equitable, and accessible educational efforts that will improve FA outcomes and eliminate FA-related disparities for these understudied and historically marginalized groups.

The prevalence of convincing FAs and the frequency of a history of severe FA reactions were lowest among those with a household income of $150 000 or more. However, paradoxically, among the few studies focused on household income and FA prevalence, previous data have suggested that those in lower income brackets have lower FA prevalence. A National Center for Health Statistics data brief reported that FA prevalence increased as income level increased from 1997 to 2011.29 The prevalence of FA was reported in reference to the national poverty level at the time of analysis: less than 100% of the poverty level, between 100% and 200%, and above 200%, which differ from the 5 categories used for the analyses of our study. In addition, only 0.6% of children enrolled in Medicaid had an FA diagnosis30 compared with the general population of children with a confirmed, physician-diagnosed FA prevalence rate of 5%.1 However, children and adults enrolled in Medicaid may not be able to obtain an accurate physician diagnosis of FA because there is less access to specialist care. Many private practices do not accept Medicaid coverage,31 and academic centers that accept it are concentrated in urban areas, a challenge for individuals living in suburban or rural areas. The limited access to care may inflate self-reported or parent-reported FAs because there is a barrier to obtaining clinical assessments and diagnostic testing, such as skin prick tests, specific IgE assessments, and oral food challenges, to identify cases of FA. Fewer reports of severe FA reactions among individuals with higher household incomes may be associated with having more access to FA management. Individuals using government-sponsored nutritional support programs have difficulty accessing allergen-free options.32 Only 1 in 2 children with an FA enrolled in Medicaid have a filled EAI prescription.33 Although further research is necessary to better understand the potential association of household income with FA outcomes, these findings emphasize the importance of socioeconomic factors as likely associated with FA outcomes by race and ethnicity. These socioeconomic factors should be factored into future analyses of the association of race and ethnicity with FA because these social constructs may influence each other.

000 or more. However, paradoxically, among the few studies focused on household income and FA prevalence, previous data have suggested that those in lower income brackets have lower FA prevalence. A National Center for Health Statistics data brief reported that FA prevalence increased as income level increased from 1997 to 2011.29 The prevalence of FA was reported in reference to the national poverty level at the time of analysis: less than 100% of the poverty level, between 100% and 200%, and above 200%, which differ from the 5 categories used for the analyses of our study. In addition, only 0.6% of children enrolled in Medicaid had an FA diagnosis30 compared with the general population of children with a confirmed, physician-diagnosed FA prevalence rate of 5%.1 However, children and adults enrolled in Medicaid may not be able to obtain an accurate physician diagnosis of FA because there is less access to specialist care. Many private practices do not accept Medicaid coverage,31 and academic centers that accept it are concentrated in urban areas, a challenge for individuals living in suburban or rural areas. The limited access to care may inflate self-reported or parent-reported FAs because there is a barrier to obtaining clinical assessments and diagnostic testing, such as skin prick tests, specific IgE assessments, and oral food challenges, to identify cases of FA. Fewer reports of severe FA reactions among individuals with higher household incomes may be associated with having more access to FA management. Individuals using government-sponsored nutritional support programs have difficulty accessing allergen-free options.32 Only 1 in 2 children with an FA enrolled in Medicaid have a filled EAI prescription.33 Although further research is necessary to better understand the potential association of household income with FA outcomes, these findings emphasize the importance of socioeconomic factors as likely associated with FA outcomes by race and ethnicity. These socioeconomic factors should be factored into future analyses of the association of race and ethnicity with FA because these social constructs may influence each other.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Although this study used US Census racial and ethnic categories, each category represents a heterogeneous population, of which we did not individually analyze subpopulations. Limitations also exist in the collapsed classification of multiracial individuals and other races. Due to the limited sample size of multiracial individuals, individuals of other races, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander individuals, and American Indian or Alaska Native individuals, they were categorized as individuals of other races for the purposes of these analyses. In addition, our findings were limited by their reliance on self-reported or parent-reported data. Self-reported or parent-reported data are subject to recall bias and often overpresent FA cases because individuals may mistakenly include intolerances and oral allergy syndrome as an FA. It is not as accurate as the criterion standard oral food challenge used to identify a true clinical FA. However, oral food challenges are not feasible to estimate FA prevalence on a national level because they are costly and time-consuming. Recognizing the potential clinical underrepresentation and overestimation of FA using self-reported or parent-reported data, this study implemented a strict, convincing FA definition considering symptoms and food allergens to reasonably estimate FA prevalence. Finally, the survey was conducted only in English and Spanish, which may have led to underrepresentation of Asian populations and other immigrant populations with limited English- or Spanish-language fluency.

Conclusion

This survey study suggests that, in the US, Asian, Black, and Hispanic populations appear to experience greater FA burden compared with their White counterparts. Further efforts should be undertaken to evaluate the sociocultural and economic covariates associated with racial and ethnic differences in FA burden and to explore additional factors such as cultural heterogeneity within racial and ethnic groups experiencing FAs. Additional targeted, educational interventions may address disparities in FA outcomes and improve targeted FA management.

Notes

Supplement 1.

eFigure. Prevalence of Convincing and Physician-Confirmed Food Allergy by Age, Estimated Across Racial, Ethnic, and Household Income Strata

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.18162

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/150005607

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.18162

Article citations

Racial and Ethnic Representation in Food Allergen Immunotherapy Trial Participants: A Systematic Review.

JAMA Netw Open, 7(9):e2432710, 03 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39283639 | PMCID: PMC11406388

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Key factors that influence quality of life in patients with IgE-mediated food allergy vary by age.

Allergy, 79(10):2812-2825, 02 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39096008

The role of pediatricians in the diagnosis and management of IgE-mediated food allergy: a review.

Front Pediatr, 12:1373373, 30 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38873581

Review

Food Insecurity and Health Inequities in Food Allergy.

Curr Allergy Asthma Rep, 24(4):155-160, 29 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38421593

Review

Health disparities in allergic diseases.

Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 24(2):94-101, 30 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38295102 | PMCID: PMC10923006

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (7) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Prevalence of Diabetes by Race and Ethnicity in the United States, 2011-2016.

JAMA, 322(24):2389-2398, 01 Dec 2019

Cited by: 303 articles | PMID: 31860047 | PMCID: PMC6990660

Associations of Race/Ethnicity and Food Insecurity With COVID-19 Infection Rates Across US Counties.

JAMA Netw Open, 4(6):e2112852, 01 Jun 2021

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 34100936 | PMCID: PMC8188266

State Variation in Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Incidence of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Among US Women.

JAMA Oncol, 9(5):700-704, 01 May 2023

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 36862439 | PMCID: PMC9982739

Temporal trends and racial/ethnic disparity in self-reported pediatric food allergy in the United States.

Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 112(3):222-229.e3, 07 Jan 2014

Cited by: 58 articles | PMID: 24428971 | PMCID: PMC3950907

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

1

,

2

1

,

2