Abstract

Free full text

Use of adapted or modified methods with people with dementia in research: A scoping review

Abstract

People with dementia are excluded from research due to methodological challenges, stigma, and discrimination. Including perspectives of people with dementia across a spectrum of abilities is essential to understanding their perspectives and experiences. Engaging people living with dementia in qualitative research can require adaptation of methods.

Qualitative research is typically considered when researchers seek to understand the perspectives, lived experiences, or opinions of individuals’ social reality. This scoping review explores current use of adapted methods with people with dementia in qualitative research, including methods used and impacts on the engagement as it relates to meeting accessibility needs. This review considered rationales for adaptations provided by authors, particularly whether authors identified a human rights or justice rationale for adapting methods to promote accessibility and engagement.

This review began with a search of primary studies using qualitative research methods published in English in OECD countries from 2017 to 2022. Two reviewers screened titles and abstracts for inclusion. Full texts were reviewed, and data from included studies were extracted using a pre-determined chart. Content analysis of rationales was conducted and reviewed by all authors. Studies were assessed for findings related to impacts of adapted methods.

Twenty-eight studies met inclusion criteria. Adaptations to qualitative research methods ranged from minor changes, such as maintaining a familiar interviewer, to more extensive novel methods such as photo-elicitation techniques. Twenty-seven studies provided a rationale for adapting their methods. No studies assessed impacts of their methodology on engagement or accessibility. Five studies observed that their methodology supported engagement.

This review helps understand the breadth of adaptations that researchers have made to qualitative research methods to include people with dementia in research. Research is needed to explore adaptations and their impact on engagement of persons with dementia with a range of abilities and backgrounds.

Introduction

People with dementia have historically been excluded from research due to challenges with communication as well as concerns about cognitive decline and capacity (Alsawy et al., 2017; Cottrell & Schultz, 1993; Swaffer, 2016; Tyrrell et al., 2006). People living with dementia have also been routinely excluded from research due to stigma that exists about their ability to provide consent to participate in research and engage in decision making (Tanner, 2012; Wilkinson, 2002). Further, there exists a broad lack of understanding about dementia, and many people may assume that people living with dementia cannot contribute meaningfully to research activities (Phillipson & Hammond, 2018).

Barriers to the participation of people with dementia in research exist due to changes common with dementia, but also because of researchers’ ability to accommodate these changes. People living with dementia often experience significant challenges with several cognitive domains, including memory, attention, perception, language, and executive function, which can negatively impact an individual’s ability to participate in, or engage with, traditional approaches to research (Waite et al., 2019). In addition, most people living with dementia live with other chronic conditions that can make engagement in research challenging (Griffith et al., 2016; Jellinger & Attems, 2015; Tonelli et al., 2017).

Each person living with dementia is unique. Dementia as a disease is heterogeneous in presentation in the areas of cognition, function, behaviour, and affect (Cohen-Mansfield, 2000). Indeed, many people living with dementia express a desire to be included in research that shapes policy and practice which impacts their lives (Dementia Action Alliance, 2010). While the experiences, concerns, needs of people living with dementia vary at an individual level, so too do their capabilities, and thus needs for support to engage in research activities vary. To understand the diverse lived experience and needs, desires, and abilities of people with dementia, it is necessary to include people with a range of capabilities to gain a fulsome understanding of their experiences and needs (Heggestad et al., 2013; McKeown et al., 2010). Adapted and modified research methods can serve to promote the inclusion of a diverse range of people living with dementia, especially those who may require additional accommodations to support their participation.

The involvement of people living with dementia in research is also a human rights concern. The World Health Organization (WHO) (2015) Plan stated that people with disabilities, including those living with dementia, have unique experiences and insights but have been excluded from the development of policies, laws, and services that impact their lives. People with disabilities should be involved in efforts to remove barriers that limit access to the assertion of their rights, including research (WHO, 2015). It is also important to consider the role of research ethics in the engagement of people with dementia as research participants. The Belmont Report (1978) identified that all research participants must be afforded three basic ethical principles – Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice. The principle of Justice is especially relevant for research with people with dementia, as they are often systematically excluded based on assumptions about their capacity without consideration of their actual abilities (Rushford & Harvey, 2016). The principle of Justice relates to the equitable treatment of research participants, and states that participants should not be denied from potential benefits of the research without ‘good reason’, or have any burden placed on their participation unduly. Participants should not be systematically excluded due to their race or ethnicity, health status, or age. Further, participants should be selected for reasons directly related to the problem being studied (The Belmont Report, 1978).

While ethical principles, as outlined above, support the inclusion of people living with dementia in research – institutional research ethics procedures often pose barriers to their inclusion. The procedural requirements of institutional research ethics boards and committees may lead researchers to exclude people with dementia from their research as a method of avoiding barriers imposed by institutional ethics boards relating to the mental capacity of people with dementia (Fletcher, 2021). While research ethics boards may consider all people with dementia to lack the capability to provide informed consent research and broader policy supports that individuals with diminished capacity have the right to participate in research, if desired, and can provide reliable accounts of their personal experiences (Beattie et al., 2015; National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Australian Research Council and Universities Australia, 2007; O’Connor et al., 2022; Rushford & Harvey, 2016). As supported by O’Connor et al. (2022), representation from people living with dementia across all stages is necessary to improve quality of care and life. Dementia Enquirers, an independent research initiative in the UK, supports people living with dementia to conceive, lead, and carry out research independent of traditional frameworks. This approach focuses on the priorities and leadership of people with dementia within research, recognizing that institutional rules intended to protect people with dementia exclude them in practice (Davies et al., 2022). Further, involving a diverse range of people with dementia, in research and policy is essential for supporting their human rights and upholding the ethical principle of Justice in research.

Qualitative research is typically considered when researchers seek to understand individuals’ social reality, including their attitudes, beliefs, and motivations. When looking to understand the perspectives and experiences of people living with disabilities, including people living with dementia, qualitative research is often argued to be the most appropriate mechanism of study (O’Day et al., 2002). However, qualitative research often requires participants to recall information about their experiences and express these experiences, most often in a verbal interview and this approach can be quite challenging for older adults with dementia (Phillipson et al., 2019).

For the purposes of this review, accessible research methods were broadly defined as adapted or modified techniques that attempt to support the participation of people with dementia in qualitative research by making the process of research easier. These techniques can include adapting to the hearing, visual, cognition, memory, and communication needs of people with dementia in the data collection process. Accessible strategies to minimize confusion, maximize meaningful engagement, and support the abilities of people with dementia are necessary when examining the individual lived experiences of dementia (Phillipson & Hammond, 2018). Facilitators to engaging people with dementia can include ensuring clear, accessible communication and maintaining flexible attitudes and approaches to research while considering an individual’s strengths, skills, preferences, and needs (Waite et al., 2019). Engagement in research activities can also include active participation during data collection efforts. Additional challenges related to ethical and consent processes as well as recruitment often need to be navigated when engaging people living with dementia as participants in research.

Phillipson et al. (2019) have identified that accessible methods are needed in dementia research to help capture the perspectives of people living with dementia in research who may require additional supports to participate. Outside of traditional institutional research, researchers in the field of creative methods in dementia research have prioritized the inclusion of people living with dementia. Examples include Cracked: new light on dementia, a stigma-challenging play and film, and Well-making, which examines crafts and creative arts as avenues for expression and reflexive research (Kontos et al., 2020; Rana et al., 2020). Researchers have also identified an urgent need for new methods that work to engage people with dementia in research to incorporate their perspectives (Heggestad et al., 2013; McKeown et al., 2010). The use of adapted or modified methods in qualitative research with people with dementia is necessary to include the perspectives of people living with dementia in research. Further, it is important to understand the methods currently being used in research with people with dementia, why they are used, and if they are effective at achieving the goal of making research more accessible. Understanding the use and impact of adapted methods can enable the inclusion of a more diverse range of people with dementia in research.

Review questions

1. What types of adapted or modified methods are used to involve people with dementia as participants in qualitative research studies?

2. How do researchers describe their rationale for using adapted or modified methods with people with dementia in qualitative research?

3. How is the use of adapted or modified methods discussed in relation to improving engagement of people with dementia in research activities?

Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the guidelines set by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis (2020). The JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis brings together scoping review methods proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and Levac et al. (2010) and thus adds consistency in methodology and reporting through developing a scoping review standard (Tricco et al., 2016). The scoping review conforms to the reporting standard of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2016).

Inclusion criteria

Participants.

Participants of selected studies included people living with dementia of any age and gender. Sources included participants that either had a diagnosis of dementia or self-identified as a person living with dementia. Dementia is generally defined as loss or impairment of memory, language, problem-solving, and other thinking abilities that are severe enough to interfere with daily life (Gaugler et al., 2021).

Concepts.

Adapted or modified methods are defined as flexible and adaptable strategies that promote meaningful communication, such as supportive modifications (i.e., promoting the comfort of participants by allowing for choice in location or time of participation), communication techniques (i.e., modifying traditional research methods like interviews to be more accessible), conversational approaches (i.e. storytelling), augmentative and alternative communication methods (i.e. picture boards, speech-generating technologies), or any other non-observational method that moves beyond traditional interviews or surveys (i.e. arts-based methods, Photovoice).

The overarching concept of interest was to understand the current use of adapted or modified methods, why such methods are used, and their impact on the engagement or accessibility of research for people with dementia. Human rights or ethical principles of justice approaches to the use of adapted or modified methods to improve the engagement of people living with dementia in qualitative research is also of interest to gauge the extent to which current research refers to adaptations and modifications as a way to meet the needs of people with dementia to exercise their right to participate. Human rights or ethical principles of justice approaches are defined as overarching frameworks connected to declarations protecting people from discrimination and promoting equality, such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations General Assembly, 2007), Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982), Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948), or Research Ethics Statements such as the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (2018), and The Belmont Report (1978).

Engagement is defined as “the act of being occupied or involved with an external stimulus” (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2011, p. 860) which includes duration (time in seconds that the participant is involved with a stimulus), attention (manipulation of the stimulus, gaze, and verbal behavior directed to the stimulus), attitude (positive or negative stance toward the stimulus), and refusal (acceptance or rejection of the stimulus) (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2011). Thus, increased engagement would generally include increased duration and attention to a stimulus (e.g., a research activity or data collection activity), positive attitude towards the activity, and decreased refusal or rejection of the activity.

Types of sources.

In this review, we considered published primary studies that involved people with dementia as direct participants and had descriptions of the types of adaptations or modifications made to their methods. Studies identifying a qualitative research design, or a mixed-method design with qualitative methods, were included. For mixed methods studies, only qualitative data and findings were included. Although some have recommended that scoping reviews include both published and grey literature (Pham et al., 2014; Tricco et al., 2016), this study focused only on published peer-reviewed articles because the aim is not solely to identify the use of these concepts in general but also to map the way scholars use the concept of adapted and modified methods in relation to dementia, human rights or justice approaches, and engagement.

Search strategy

All searches were conducted between May 2022 and December 2022 across PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases.

Peer-reviewed literature.

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a research librarian at the University of Waterloo. Search strings included keywords such as: “qualitative”, “adapted”, “modified”, “accessible”, “dementia”, “engagement”, as well as their related terms, MeSH terms, and synonyms. To align with the JBI method, a three-step search strategy was used. The first step of the scoping review involved an initial limited search of PubMed and Scopus. This was followed by an analysis of the text words contained in the titles and abstracts of retrieved papers, and of the index terms used to describe the articles to determine additional search terms. A second search using all identified keywords and index terms was then undertaken across all included databases. Third, the reference lists of the sources that were selected were searched for additional sources. Only sources published between 2017 and 2022 and in the English language and in an OECD country were included to capture the current state of the literature.

Selection of sources of evidence

Results of the search were collated and uploaded into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, n.d.) and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by two reviewers, the first author (E.C.) and a trained research assistant, using the inclusion criteria for the review. Disagreements were resolved through discussions with a member of the research team (C.M.). Full texts of references were retrieved and assessed by two reviewers against the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Charting the data

Included sources were examined to extract key information of the source, author, reference, and methods relevant to the review questions. Specifically, the included sources were examined for study design, data collection methods and procedures, the type of adaptation or modification included, and information about the participants, sample size, inclusion and exclusion criteria, study location, and recruitment methods. The study outcomes were also extracted, focusing on any outcomes of adaptations made to the study method or procedure, and any findings related to accessibility, inclusion, or engagement. The rationales for adaptations or modifications made were also captured. Information on whether a rationale was a given, and if so, if it related to human rights or ethical principles of justice was extracted. If a rationale was discussed that was not related to the two aforementioned categories, it was detailed for further examination and categorization.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting results

After completion of the data extraction, the characteristics of all included studies were tabulated. A descriptive qualitative content analysis (Creswell & Poth, 2016) was conducted using NVivo 12 (QSR International) to examine and categorize the rationales for use of adapted or modified methods provided by authors. A summary of data coded is provided in the form of categories. A narrative summary describing how the results relate to the objectives of the review was created, including a discussion of gaps in the literature.

Results

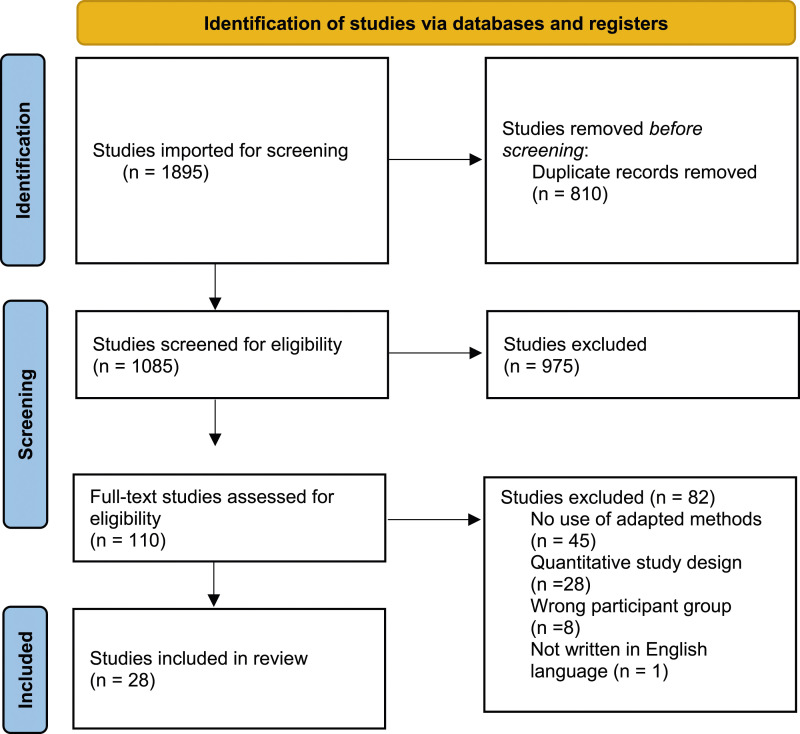

The database search identified 1895 abstracts. After the removal of duplicates, 1085 articles remained. A total of 975 articles were excluded after title and abstract review, and 110 articles underwent full-text review. Eight conflicts were identified at the full-text stage and a third reviewer (C.M.) was involved to resolve the conflicts. The final sample included 28 peer-reviewed articles (see Figure 1).

Studies included were from the UK (n = 15), Canada (n = 2), Australia (n = 2), the USA (n = 1) and other countries (n = 8). Research on this topic has grown over time. None of the included studies were published in 2017; 7% were published in 2018, 32% in 2019, 14% in 2020, 39% in 2021, and 7% in 2022 (Table 1). The majority (79%) of studies cited a qualitative research design, and the remainder were identified as mixed methods. All studies included people with dementia (n = 439). Studies also included care partners (n = 380) and health and social care providers or other stakeholders (n = 263). A comprehensive, descriptive table (Table 4) detailing characteristics of all included studies is presented in Appendix 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Total number of sources of evidence: 28 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of publication | Number of studies, per year | Types of studies | Rationale type | Outcomes | Summary of rationales |

| UK: 15 | 2017: 0 | Qualitative: 24 | Human rights: 9 | No studies assessed the impacts of their methodology on engagement | Adaptations ensure voices are included: 8 |

| Canada: 2 | 2018: 2 | Mixed methods: 4 | Ethical/Justice: 9 | 5 studies observed that their methodology supported engagement | Adaptations promote conversation: 7 |

| Australia: 2 | 2019: 9 | No rationale: 1 | Adaptations are best practice: 4 | ||

| USA: 1 | 2020: 4 | Other (not classified in any of the above): 19 | Improve overall research output: 2 | ||

| Other: 8 | 2021: 11 | Adaptations promote comfort: 1 | |||

| 2022: 2 | |||||

Types of adaptations and modifications made

While all studies included in this review necessarily used adapted or modified data collection methods, the types of adaptations and modifications made varied. Seventeen studies included cognitive and communication accessible strategies, such as providing interview questions in advance to support participation and using easy-to-understand language. Fifteen studies adapted to personal preference, such as maintaining a familiar interviewer or researcher, and encouraging participants to engage in the data collection activity at a time or place comfortable to them. Eleven studies included novel data collection approaches, such as photo-elicitation techniques (e.g., using visual images to elicit comments) and nominal group sessions (e.g., structured small group sessions to reach decisions). Eight studies employed flexibility in data collection methods, such as giving options for participation (e.g., participant could choose between a survey, interview, and the method of data collection such as in person or over the phone). Four studies included modifications to capture non-verbal communication, such as capturing the interview activities on video or taking notes on body language. Details of adaptations and modifications made in included sources are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of adaptations and modifications.

| Adaptation/Modification type | Details | Citations (first author, Year) |

|---|---|---|

| Accessible communication strategies | Providing clear communication in data collection, such as plain-language consent forms and information sheets, providing interview questions in advance, using easy-to-understand language and direct questions in interview guides, displaying interview questions visually, reducing the number of questions asked, providing prompts when participants experienced challenges responding, and giving ample time for response | Barrado-Martin, 2019 |

| Asghar, 2020 | ||

| Ward, 2020 | ||

| Sheth, 2019 | ||

| Stephan, 2018 | ||

| Krein, 2020 | ||

| Novek, 2021 | ||

| Gebhard, 2021 | ||

| Tetrault, 2022 | ||

| Kwak, 2018 | ||

| Hoel, 2021 | ||

| Talbot, 2021 | ||

| Capstick, 2021 | ||

| Morbey, 2019 | ||

| Fleetwood-Smith, 2022 | ||

| Keogh, 2021 | ||

| Tiersen, 2021 | |

| Adapting to personal preference | Supporting the comfort and preferences of the participant. Strategies may include keeping a consistent or familiar interviewer/researcher, conducting data collection at a time or place preferred by the participant, including the option to have a support person or care partner present, creating a sense of security | Barrado-Martin, 2019 |

| Thompson, 2022 | ||

| Keyes, 2019 | ||

| Ward, 2020 | ||

| Weeks, 2020 | ||

| Krein, 2020 | ||

| Novek, 2021 | ||

| Gebhard, 2021 | ||

| Funnell, 2019 | ||

| Tetrault, 2022 | ||

| Kwak, 2018 | ||

| Schnelli, 2020 | ||

| Fleetwood-Smith, 2022 | ||

| Keogh, 2021 | ||

| Bartlett, 2019 | |

| Novel data collection approaches | Think-aloud techniques; narrative interviews using objects, pictures, or photographs from around the participant’s home; photo-elicitation techniques; nominal group sessions (e.g., structured group brainstorming); invitation to respond techniques (e.g., direct calls to respond from interviewer); using life story books; walking interviews; reflective storytelling techniques; and a café method | McCombie, 2020 |

| Kindell, 2019 | ||

| Ward, 2020 | ||

| Sheth, 2019 | ||

| Funnell, 2019 | ||

| Kwak, 2018 | ||

| Hicks, 2021 | ||

| Talbot, 2021 | ||

| Capstick, 2021 | ||

| Keogh, 2021 | ||

| Bartlett, 2019 | |

| Flexibility in data collection methods | Using general or broad interview questions (i.e., not conforming to any one particular interviewing technique but purposely being flexible), giving options for participation (i.e., through a survey or interview) | Øksnebjerg, 2019 |

| Krein, 2020 | ||

| Novek, 2021 | ||

| Stamou, 2021 | ||

| Hicks, 2021 | ||

| Hoel, 2021 | ||

| Morbey, 2019 | ||

| Fleetwood-Smith, 2022 | |

| Capturing non-verbal communication | Capture non-verbal communication expressed by participants | Barrado-Martin, 2019 |

| Ward 2020 | ||

| Capstick, 2021 | ||

| Fleetwood-Smith, 2022 |

Types of rationales provided

Of the included studies, 27 of the 28 provided rationales for adapting or modifying methods used with participants with dementia, and some studies provided more than one rationale. Studies could be broadly considered to have provided ethical considerations, to promote justice, and/or methodological considerations, to promote participation. Nine studies rationalized adaptations or modifications on the basis of ethical principles of justice, which reflect that it is unjust to exclude people with dementia without accommodations. Nine studies provided rationales related to human rights, that is, people living with dementia have the right to participate in research if they so choose. Eight studies provided rationales for adaptations or modifications made to methods related to ensuring the participant’s voice was included, however, did not discuss such inclusion in terms of relation to an ethical principle of justice approach. Seven justified the adaptations or modifications made to promote conversation. For example, Barrado-Martín et al. (2019) emphasized that utilizing an invitation-to-respond technique was necessary to facilitate and promote the involvement of participants in conversation. Four rationalized the adaptations or modifications made as aligning to best practice or guidance from experts, such as Keyes et al. (2019), who cite the work of Clarke and Keady (2002) in the development of their inclusive data collection procedure. Two justified the adaptation or modification of methods as a way to improve the relevance of the research output through including ‘end users’ in the research process. One study provided a rationale for adapting or modifying methods to promote the comfort of participants involved, which included emphasizing the role of the data collection facilitator in promoting participant comfort through feelings of safety. There were no clear connections identified between the type of rationale and the type of adaptation employed by the authors. Characteristics of rationales provided in included sources are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of rationales provided for adapting or modifying methods.

| Rationale | Characteristics | Citations (first author, Year) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical rationales promoting justice | Rationales related to ethical principles of justice, e.g., adapting or modifying methods to ensure participation as it is unjust to exclude people on the basis of disability | Ward, 2020 | 9 |

| Krein, 2020 | |||

| Funnell, 2019 | |||

| Hoel, 2021 | |||

| Capstick, 2021 | |||

| Morbey, 2019 | |||

| Schnelli, 2020 | |||

| Fleetwood-Smith, 2022 | |||

| Bartletta, 2019 | |||

| Rationales related to human rights of people with dementia to participate on an equal basis with others | Ward, 2020 | 9 | |

| Weeks, 2020 | |||

| Stephan, 2018 | |||

| Funnell, 2019 | |||

| Tetrault, 2022 | |||

| Capstick, 2021 | |||

| Fleetwood-Smith, 2022 | |||

| Tiersen, 2021 | |||

| Bartletta, 2019 | |||

| Rationales related to ensuring participants voices were included | McCombie, 2020 | 8 | |

| Sheth, 2019 | |||

| Novek, 2021 | |||

| Gebhard, 2021 | |||

| Hicks, 2021 | |||

| Talbot, 2021 | |||

| Keogh, 2021 | |||

| Ward, 2020 | |||

| Methodological rationales promoting participation | Rationales justifying the use of adaptations or modifications to methods through highlighting the need for adaptations to promote conversation with people with dementia | Barrado-Martín, 2019 | 7 |

| Sheth, 2019 | |||

| Kwak, 2018 | |||

| Krein, 2020 | |||

| Gebhard, 2021 | |||

| Asghar, 2020 | |||

| Thompson, 2022 | |||

| Rationales that discussed adaptations or modifications to methods being made as they were considered to be best practice or advised by experts | Kindell, 2019 | 4 | |

| Keyes, 2019 | |||

| Tiersen, 2021 | |||

| Krein, 2020 | |||

| Rationales related to including people with dementia through adapted or modified methods to improve the research outcomes in terms of their relevance or applicability | Øksnebjerg, 2019 | 2 | |

| Asghar, 2020 | |||

| Rationale was related to ensuring participants felt comfortable during the interviews | Thompson, 2022 | 1 | |

| No rationale provided | No rationale for making adaptations or modifications to methods | Stamou, 2021 | 1 |

Supporting the engagement of people living with dementia in research

While all included studies included adaptations or modifications with participants with dementia, no studies assessed the impact of adaptations or modifications on the engagement of participants. Five studies observed that adaptations or modifications increased the engagement of participants, such as reporting that participants seemed more open to discussions about their feelings (Bartletta et al., 2019), seemed more relaxed (Hicks et al., 2021), participated in more conversation (Capstick et al., 2021), experienced reduced barriers (Morbey et al., 2019), and provided more information in their responses (Fleetwood-Smith et al., 2022).

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to understand the ways in which qualitative research methods have been adapted and modified to involve people living with dementia and research. The review mapped the nature of adaptations and modifications, as well as any discussions of how these adaptations or modifications might impact the accessibility of research methods. Adaptations and modifications ranged from supportive changes, such as promoting comfort through using a familiar facilitator, to more extensive modifications, such as using photograph prompts and novel methods. The accessibility of research methods, as tied to the adaptations or modifications made to accommodate the participation needs of individuals with dementia, was also examined in light of any discussions of improved engagement for participants with dementia.

As supported by the results of this review, various adaptations and modifications can be made to support the participation of people with dementia in research activities. The impact of these adaptations or modifications on the engagement of people with dementia in research (i.e., whether they are effective at accommodating participants needs) and the data produced remains relatively unstudied. Indeed, no studies identified in this review provided any evaluation of how adapted or modified methods being used impacted the engagement of people with dementia, or the outcomes of the research. Ensuring methods employed are effective at capturing a diverse range of perspectives of people living with dementia is essential to integrating such perspectives in policy and practice. It is argued that in order for the rights of people with dementia to be upheld, and for the outcomes of research to be translated into policies, laws, and services that impact their lives, rigorous research methodology must be employed to ensure maximum uptake and transferability of results into practice (WHO, 2015). A recent study by McArthur et al. (2023) identified that barriers exist to the inclusion of people living with dementia in research, highlighting the importance of adapted or modified research methods to engage people living with dementia in research. In alignment with the present review, the authors emphasize the need to examine the effect of including people living with dementia in research (McArthur et al., 2023). It is concluded that future research should seek to examine the methodological rigour of such adapted and modified methods.

A secondary focus of this review was to examine the rationales used by researchers who involved people with dementia in qualitative research activities through using adapted or modified methods. Researchers have a role in ensuring their studies are accessible to their participants. Creating a safe and accessible study procedure can support people with dementia’s right to participate (Cridland et al., 2016; Novek & Wilkinson, 2019; Wilkinson, 2002). Ensuring accessibility in research promotes the inclusion and participation of people living with dementia (Hobson et al., 2019). Future research should seek to include transparent discussions of methods employed to promote the uptake of accessible methods to engage people living with dementia.

In this scoping review, we identified 28 studies that included adaptations or modifications to their study methods for including people living with dementia. Twenty-seven of the included studies provided a rationale for adapting or modifying their methods. How authors rationalize adaptations and modifications is important when considering how this impacts the rights of people living with dementia to participate. Understanding why adaptations and modifications are made can help to encourage future research to incorporate accessibility adaptations that support participation for people living with dementia. In turn, this can help to support more accessible research for people with dementia in the future. While 5 studies observed that the adaptations or modifications made had an impact on the engagement of people with dementia in research, no studies assessed the impact of adaptations or modifications on the engagement of participants. As such, there is a gap within the literature of understanding how such adaptations or modifications may impact engagement, as well as research outcomes.

Limitations

This review was limited to English-language, peer-reviewed literature published between 2017 and 2022. While a rigorous search method was employed, it is possible that relevant literature could have been missed. The conclusions drawn from this review are based on the included descriptions of adaptations or modifications, and assessments made are limited to the level of detail provided by authors. Our understanding of the scope of the literature concerning the use of adapted or modified methods with people living with dementia is also limited to information published in English, and thus may not capture approaches to engaging with people living with dementia present in non-English literature – including culturally specific approaches. Thus, it is possible that this review presents an under-estimation of adaptations or modifications occurring in practice.

Conclusion

Globally, calls have been made to improve the inclusion of people living with disabilities, including those living with dementia, in research that impacts policy and practice as a way to recognize their rights to participate on an equal basis with others. However, inadequate information exists to support researchers to promote engagement of people living with dementia in research and support their participation with accessible research methods. While included studies showcase a range of adaptations and modifications that can be made to research methods for studies seeking to involve people living with dementia in research, there is limited information on how adaptations or modifications were chosen and implemented, and no assessment of how such adaptations or modifications actually impacted participants’ experiences with participating. Such limited evidence makes it difficult to prioritize the meaningful inclusion of people living with dementia in future studies. Comprehensive methodology sections with highly specific details of adaptations, modifications, and their impacts on engagement of people with dementia in the research process are needed to enhance the understanding of the opportunities for adaptations and modifications. This in turn can help to promote the recognition of the rights of people with dementia to participate in research. Future research should examine the impact of adaptations or modifications to methods in studies that include people with dementia as research participants on engagement.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Research Librarian Jackie Stapleton for her contributions to the development of the scoping review protocol. Research Assistants Samantha Liu and Ruah Alsaghier provided assistance with reference screening.

Biography

Emma Conway, MA: PhD Candidate, School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo. Emma Conway is a PhD Candidate in the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo. Emma’s work focuses on understanding the accessibility and inclusivity of qualitative research methods for engaging people with dementia in qualitative research to support people with dementia’s rights to participate.

Ellen MacEachen, PhD: Professor and Director, School of Public Health Sciences. Ellen MacEachen is a Professor in the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo. Her research examines vulnerable workers, precarious employment, and the changing nature of work. She specialises in qualitative research methodology and works closely with community partners and policy makers to ensure research relevance and improve research impact.

Laura Middleton, PhD: Associate Professor and Associate Chair of Applied Research, Partnerships and Outreach, Department of Kinesiology and Health Sciences, University of Waterloo. Laura Middleton is an Associate Professor and the Associate Chair of Applied Research, Partnerships and Outreach in the Department of Kinesiology and Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo. She aims to identify strategies to promote health, function, and well-being of those living with, or at risk for, dementia. She partners people living with dementia, care partners, health care professionals, and community service providers as co-researchers to create accessible and effective supports and interventions.

Carrie McAiney, PhD: Associate Professor, School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, Schlegel Research Chair in Dementia, Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging. Carrie McAiney is Associate Professor in the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo, and the Schlegel Research Chair in Dementia and Scientific Director of the Murray Alzheimer Research and Education Program at the Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging. As a health services researcher, Carrie works collaboratively with persons living with dementia, family/friend care partners, providers, and organizations to co-design, implement and evaluate interventions and approaches to enhance the well-being of persons living with dementia and family/friend care partners.

Appendix 1.

Table 4.

Summary of studies that have used adapted or modified methods to involve people with dementia.

| Authors | Year | Title | Aim | Sample | Setting | Adaptation or modification used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwak, Won Han, & Ha | 2018 | Telling life stories: a dyadic intervention for older Korean couples affected by mild Alzheimer’s disease | Examine how older Korean couples dealing with dementia experience the life story approach intervention through examining responses to a survey, as well as through interviews | 56 | Community | Researchers were provided with training to encourage participation. Supported communication by referring to old photographs, repeating questions and giving ample time to respond. Utilized the Life Story Book to support conversation. Used short sentences to help participants understand the interview questions |

| Stephan, Bieber, Hopper, Joyce, & Irving et al. | 2018 | Barriers and facilitators to the access to and use of formal dementia care: findings of a focus group study with people with dementia, informal carers and health and social care professionals in eight European countries | Explore the barriers and facilitators of formal care for persons with dementia, their care partners, and health professionals through focus groups | 51 | Nursing home | Focus groups were kept smaller. Pictures showing typical caregiving situations were included in the focus groups to promote conversation and ensure understanding of the topic |

| Bartletta & Brannelly | 2019 | On being outdoors: How people with dementia experience and deal with vulnerabilities | Understand how vulnerability is experienced by people with dementia in the outdoor environment through walking interviews | Phase 1: 16, Phase 2: 15 | Community | The method of walking interviews was employed by combining observations and interviews with participants with dementia during their everyday routine. Supported rapport building and conversation through situating the interview in a comfortable space. Participants engaged in conversation when supported through the walking interview and when the researchers showed an interest in their life. The length of the walking interviews was based on the participants' needs. Attention was paid to how the person responded during the research process and participation was abandoned if any distress was shown |

| Barrado-Martín, Heward, Polman, & Nyman | 2019 | Acceptability of a Dyadic Tai Chi Intervention for Older People Living with Dementia and Their Informal Carers | Investigate acceptability of Tai Chi exercise interventions in meeting the needs of PWD and care partners through focus groups, observations, field notes, and instructor feedback | 10 | Community | The facilitators of the focus groups were familiar. Non-verbal communication was noted. To facilitate conversation, printed copies of the focus group questions were provided to the participants |

| Funnell, Garriock, Shirley, & Williamson | 2019 | Dementia-friendly design of television news broadcasts | Understand the factors that influence the viewing of television news programs by participants with dementia and identify ways to improve the experience through focus groups | 5, 11, and 4 | Community | To support some participants who struggled with direct questioning, views were drawn out in a conversational manner using an invitation to respond technique. This technique encourages participants to join into the conversation through group interaction |

| Keyes, Clarke, & Gibb | 2019 | Living with dementia, interdependence, and citizenship: narratives of everyday decision-making | Examine the ways people living with dementia managed information about themselves and dementia through interviews | 16 | Community | Interviews were iterative and sequential. Importance of developing rapport evident, interviewers allow for participants to set the pace of the interviews to their own needs and preferences. Participants chose to be interviewed alone or with their care partner, location of interviews |

| Kindell, Wilkinson, & Keady | 2019 | From conversation to connection: a cross-case analysis of life-story work with five couples where one partner has semantic dementia | Examine conversations of people with dementia and investigate the utility of life-story work in facilitating communication through home visits, biographical interviews, and video/audio data | 5 | Community | Narrative interviews were employed. The interviewers used objects, pictures, or photographs from around the participants home to support those with dementia to participate. Care partners also provided support where necessary to enable participation |

| Krein, Jeon, & Miller Amberber | 2010 | Development of a new tool for the early identification of communication support needs in people living with dementia: An Australian face-validation study | Establish the face validity of the communication-support needs assessment tool for dementia by consulting people living with dementia and their close family/others who provide support | 7 | Community | Participants were given several options for feedback provision, including written feedback, or a combination of written and verbal feedback, with or without the support of a care partner to address potential communication difficulties. Participants were provided with the item pool and interview questions in advance |

| Morbey, Harding, Swarbrick, Ahmed, Elvish, Keady, Williamson, & Reilly | 2019 | Involving people living with dementia in research: an accessible modified Delphi survey for core outcome set development | Design an accessible Delphi survey with people living with dementia and care partners using the COINED model of co-research to structure consultations through interviews and group sessions | 18 | Community | The researchers adapted the Delphi method and consulted with people living with dementia to design the methodology. Adaptations were made in the consultation sessions including re-reading statements to clarify meaning. The authors modified the rating scale to include 3 instead of 5 items and stated this modification enabled participation. Additional modifications to engage with participants verbally were made. Approaches to accommodate individual means of participation were employed. Direct contact time to develop rapport with people living with dementia and working at their pace was necessary |

| Øksnebjerg, Woods, & Waldemar | 2019 | Designing the ReACT App to Support Self-Management of People with Dementia: An Iterative User-Involving Process | Understand how to design and deploy an assistive technology app through involving people with dementia in a user-centered design process | 28 | Community | Interview questions were purposefully general to enable participants to share their experiences and be flexible to their needs. To guide the interviews, and support attention and memory, questions were presented on posters |

| Sheth | 2019 | Intellectual disability and dementia: perspectives on environmental influences | Improve understandings of environmental influences on participation in routine and familiar activities for people with intellectual disabilities and dementia | 4 | Not specified | Consent forms were adapted to maximize cognitive accessibility. None of the participants were aware of their diagnosis, the term dementia or Alzheimer’s was not included in any recruitment, or consent procedures. Nominal group technique sessions were used. The methodology provided structure to support meaningful engagement in sharing perspectives |

| Asghar, Cang, & Yu | 2020 | The impact of assistive software application to facilitate people with dementia through participatory research | Analyze the impacts of the Assistive Brotherhood Community application through case studies and interviews with people with dementia | 8 | Community | The structure of the questions was kept simple, and the number of questions was reduced to accommodate potential challenges with concentration |

| Schnelli, Hirt, & Zeller | 2020 | People with dementia as internet users: what are their needs? A qualitative study | Identify the needs and expectations of people with dementia regarding dementia-related information on the internet concerning content, presentation, navigation, language, and design through interviews | 5 | Community | Followed recommendations for interviewing people with dementia including identifying willingness to participate, facilitating/stimulating the flow of the interview, creating a sense of security, adapting the interview in terms of physical and cognitive skills, and ensuring an optimal interview environment and the presence of trusted people. Developed rapport prior to the interview and ensured flexibility |

| Ward, Shack Thoft, Lomax, & Parkes | 2020 | A visual and creative approach to exploring people with dementia's experiences of being students at a school in Denmark | Explore the experiences of participants with dementia attending an adult school. This study utilized photo elicitation to learn more about the participants perspectives of the service. The photographs taken by participants were used to support focus groups | 10 | Community | The recruitment process undertaken in a familiar place to foster collaboration in the research process. Participants were given an easy-to-use digital camera for the photo elicitation phase of the study. Instructions were also attached to the camera. Researchers selected the photos to reduce burden on the participants. Small focus groups were deliberately designed to foster engagement. Questions were focused on personal experiences and emotions, rather than memory. Video recordings were made to capture nonverbal communication. Poems, storyboards, and storybooks were developed through the focus group sessions to represent the participants experiences |

| Weeks, MacQuarrie, & Vihvelin | 2020 | Planning an Intergenerational Shared Site: Nursing Home Resident Perspectives | Explore the effectiveness of an intergenerational visitation program for participants with dementia through interviews | 12 | Nursing home | Conversational interviewing was employed to facilitate engagement with the residents in a location that was comfortable to them. A less structured interview was intended to create a conversation-like atmosphere to prompt participants to engage with the researcher |

| Capstick, Dennison, Oyebode, Healy, Surr, Parveen, Sass, & Drury | 2021 | Drawn from life: Cocreating narrative and graphic vignettes of lived experience with people affected by dementia | Include participants with dementia who have varied cognitive abilities by adapting the Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement process through narrative elicitation to create vignettes of experiences with dementia services | 9 | Community | Use of storytelling/narrative elicitation enforced a person-centered approach to amplify stories of participants. The method was modified to support participation by using photo-elicitation, informal conversation, and observation. Photographs were used alongside the questions. Participants were encouraged to answer the questions through person narratives or stories |

| Gebhard & Mir | 2021 | What Moves People Living with Dementia? Exploring Barriers and Motivators for Physical Activity Perceived by People Living with Dementia in Care Homes | Investigate motivators and barriers concerning physical activity in people living with dementia in care homes in terms of the social-ecological model | 10 | LTC | The interview guide was created, and procedure developed, to enable participation. Interview questions were asked one at a time to reduce complexity. The study also pre-tested the interview guides with people at various stages of their dementia journey to ensure the interview guide was feasible. Included pictures alongside the interview questions to support verbal communication |

| Hicks, Innes, & Nyman | 2021 | Experiences of rural life among community-dwelling older men with dementia and their implications for social inclusion | Address the issue of social exclusion for rural-dwelling older men with dementia within an English county through a technological initiative through interviews | 17 | Community | Utilization of open interviews to enable meaningful insights into experiences. Walking interviews were offered |

| Hoel, Mork Rokstad, Hjorth Feiring, Lichtwarck, Selbaek, & Bergh | 2021 | Person-centered dementia care in homecare services - highly recommended but still challenging to obtain: a qualitative interview study | Understand how participants with dementia experience home care services through individual in-depth interviews | 12 | Community | The interviews were flexible to support ease of participation through moving to close-ended questions where needed. Participants were supported by experienced researchers. Consent form was written in simple language to support the participants ability to understand the information about the study |

| Keogh, Carney, & O’Shea | 2021 | Innovative methods for involving people with dementia and carers in the policymaking process | Increase the involvement of participants with dementia and care partners using innovative methods, such as a policy cafe and a carer's assembly for care partners | 10 | Community | The cafe method is discussed as being flexible and adaptable. The topics discussed were kept on the wall and tables to help participants stay on track. An information sheet was provided for clarity purposes. The venue was selected as it was familiar to participants. Decisions from the cafe proceedings were drawn out by an artist. The participants determined the length of the session |

| McCombie, Cort, Gould, Kiosses, Alexopoulos, Howard, & Lawrence | 2020 | Adapting and Optimizing Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH) for People with Mild-Moderate Dementia and Depression | Adapt and optimize problem adaptation therapy for depression in dementia through interviews and focus groups | 16 | Not specified | Interviewers used think-aloud techniques to guide sessions, to encourage open talk about how they were experiencing the intervention session as it happened, removing the need to recall session details in an interview later |

| Novek & Menec | 2021 | Age, Dementia, and Diagnostic Candidacy: Examining the Diagnosis of Young Onset Dementia Using the Candidacy Framework | Understand through semi-structured interviews the experience of accessing and receiving a diagnosis of young-onset dementia | 6 | Community | Flexible methodology was employed. The consent process was described as inclusive and rigorous. Open-ended questions were used to support conversations. Demographic information was provided by care partners. Throughout the interview, the interviewer sought ongoing process consent through restating the study aims, and monitoring for signs of discomfort. When signs of distress were observed, the interviewer offered to pause or change topics. To promote a positive interview experience, the interview sessions concluded with questions centered on the participants strengths and supports |

| Stamou, La Fontaine, O'Malley, Jones, Parkes, Carter, & Oyebode | 2021 | Helpful post-diagnostic services for young onset dementia: Findings and recommendations from the Angela project | Examine experiences of dementia service use from the perspective of people living with young-onset dementia and care partners | 10 | Community | The interview guide was developed to accommodate different degrees of cognitive impairment through two different approaches. A researcher contacted the participant by phone in advance to determine if the participant could recall the survey. A direct approach focused on in-depth discussion of participants’ survey responses was used for those who were able to recall their survey responses. An open approach was employed for those not able to recall the survey |

| Talbot, Dwyer, Clare, & Heaton | 2021 | The use of Twitter by people with young-onset dementia: A qualitative analysis of narratives and identity formation in the age of social media | Examine the role of using Twitter for people with dementia through interviews | 11 | Community | Interview guide was reviewed by 2 people with dementia to ensure that the topics were relevant, and the language used was accessible. Participants were asked questions in the interview and encouraged to engage in reflective storytelling about their experiences. In the second section of the interviews, the participants were shown a past Tweet of theirs which supported the conversation |

| Tiersen, Batey, Harrison, Naar, Serban, Daniels, & Calvo | 2021 | Smart Home Sensing and Monitoring in Households with Dementia: User-Centered Design Approach | Examine the needs of participants with dementia, care partners, and health and social care providers about smart home systems through a user-centered design process | Phase 1: 9, Phase 2: 2, Workshops: 35 | Community | People living with dementia were included in the design process of smart home technologies through participatory design approaches. The data collection approaches were discussed as being aligned to participants' abilities to foster their inclusion in the study |

| Fleetwood-Smith, Tischler, & Robson | 2022 | Using creative, sensory and embodied research methods when working with people with dementia: a method story | Explore the use of creative, sensory, and embodied research methods to understand the significance of clothing for participants with dementia in care homes through three cycles of research | Not specified | Care home | Researchers adapted the environment during the study to suit the participants with dementia's needs. Objects were used to elicit sensory and nonverbal communication. The approaches used were highlighted as enabling participants with dementia to engage in research by supporting flexible communication. The researchers volunteered at the care home prior to the study to develop rapport with the participants |

| Thompson, Tamplin, Clark, & Baker | 2022 | Therapeutic Choirs for Families Living with Dementia: A Phenomenological Study | Examine the benefits and experiences of participants with dementia and care partners who took part in community-based, therapeutic choirs through interviews | 7 | Community | Participants with dementia were provided with prompts when facing challenges with communication or recall. The interviewers built rapport with participants before the interview to maintain engagement |

| Tetrault, Nyback, Vaartio-Rajalin, & Fagerstrom | 2022 | Advance care planning in dementia care: Wants, beliefs, and insight | Explore the experiences and perspectives of people with early dementia about planning for future care through interviews | 10 | Community | Information about the study was provided in an accessible format. Language was chosen to be easy to understand |

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Emma Conway https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2616-7290

Ellen MacEachen https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6477-7650

Laura Middleton https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8624-3123

Carrie McAiney https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7864-344X

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012231205610

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/14713012231205610

Citations & impact

This article has not been cited yet.

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/155676977

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Beyond the black stump: rapid reviews of health research issues affecting regional, rural and remote Australia.

Med J Aust, 213 Suppl 11:S3-S32.e1, 01 Dec 2020

Cited by: 10 articles | PMID: 33314144

Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2(2022), 01 Feb 2022

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 36321557 | PMCID: PMC8805585

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Researchers' experiences with patient engagement in health research: a scoping review and thematic synthesis.

Res Involv Engagem, 9(1):22, 10 Apr 2023

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 37038164 | PMCID: PMC10088213

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Survivor, family and professional experiences of psychosocial interventions for sexual abuse and violence: a qualitative evidence synthesis.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 10:CD013648, 04 Oct 2022

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 36194890 | PMCID: PMC9531960

Review Free full text in Europe PMC