Abstract

Free full text

Multifaceted relationship between diabetes and kidney diseases: Beyond diabetes

Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common causes of chronic kidney disease. Kidney involvement in patients with diabetes has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from asymptomatic to overt proteinuria and kidney failure. The development of kidney disease in diabetes is associated with structural changes in multiple kidney compartments, such as the vascular system and glomeruli. Glomerular alterations include thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, loss of podocytes, and segmental mesangiolysis, which may lead to microaneurysms and the development of pathognomonic Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules. Beyond lesions directly related to diabetes, awareness of the possible coexistence of nondiabetic kidney disease in patients with diabetes is increasing. These nondiabetic lesions include focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, IgA nephropathy, and other primary or secondary renal disorders. Differential diagnosis of these conditions is crucial in guiding clinical management and therapeutic approaches. However, the relationship between diabetes and the kidney is bidirectional; thus, new-onset diabetes may also occur as a complication of the treatment in patients with renal diseases. Here, we review the complex and multifaceted correlation between diabetes and kidney diseases and discuss clinical presentation and course, differential diagnosis, and therapeutic oppor-tunities offered by novel drugs.

Core Tip: The relationship between diabetes and kidney disease is complex. Indeed, in patients with diabetes beyond the development of diabetic kidney disease, other forms of kidney disorders not directly correlated with diabetes may occur. Distinguishing between these conditions is essential to guide clinical management. Additionally, de novo diabetes may complicate the treatment of patients with kidney disease. Finally, growing evidence indicates that new drugs, such as sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, may be effective under both conditions. Herein, we discuss the multifaceted correlation between diabetes and kidney diseases, focusing on clinical presentation, differential diagnosis, and new therapeutic opportunities.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most common causes of renal disorders and chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the leading cause of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) in high-income countries[1]. Kidney involvement may be found in up to 30%-40% of diabetes patients[2] and is characterized by a wide spectrum of possible clinical entities, such as diabetic kidney disease (DKD), nondiabetic kidney disease (NDKD), and association of DKD together with NDKD[3]. Consequently, the clinical presentation may range from mild urinary alterations and low-grade proteinuria to overt proteinuria and kidney failure[4].

DKD is usually diagnosed in patients with a long history of DM (> 10 years) who present with albuminuria and/or reduced estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR). However, recent epidemiological studies have highlighted that it may also present with non-albuminuric renal impairment[5]. Clinical experience and studies have found that not all cases of CKD and urinary alterations in patients with diabetes are direct consequences of DM. Indeed, studies of kidney biopsies have shown that up to 40% of patients with a clinical diagnosis of DKD present a form of NDKD[6]. These nondiabetic lesions include focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, IgA nephropathy, and other primary or secondary glomerular diseases. Therefore, it appears clear that an approach based exclusively on clinical evaluation is insufficient to properly classify and manage patients with DM with renal damage, whereas renal biopsy remains essential for acquiring both diagnostic and prognostic information[7]. Interestingly, the relationship between DM and kidney disease is bidirectional. Therefore, although patients with diabetes may be affected by various kidney diseases, developing de-novo DM in patients with nephropathies is possible, particularly in those undergoing immunosuppressive treatment[8]. Therefore, in this opinion review, we discuss the multifaceted relationship between kidney disease and DM. Moreover, we explored new therapeutic opportunities provided by the introduction of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which were first used for their antidiabetic effects and have been shown to be potentially effective in kidney disease management[9].

WHAT ARE THE CAUSES OF CKD IN PATIENTS WITH DIABETES?

DKD

DKD is a complex and heterogeneous disease with overlapping etiological pathways. Understanding the molecular mechanism of DKD onset and progression may help optimize diagnosis and treatment. However, a full discussion of the precise pathogenesis is outside the scope of the present study; rather, it may be found in focused reviews[10,11].

Briefly, the mechanisms of DKD can be classified into changes in glomerular hemodynamics, inflammatory responses, and oxidative stress. In the early stages of DKD, one of the most characteristic alterations is glomerular hyperfiltration, which is also influenced by lifestyle factors, such as diet, body weight, and hyperglycemia[12,13]. In particular, hyperglycemia stimulates sodium-glucose cotransporters to increase the reabsorption of glucose and sodium in the proximal tubules, reducing sodium chloride delivery to the macula dense[14]. As a result, activation of the so-called tubuloglomerular feedback occurs, resulting in the dilatation of afferent arterioles and the release of angiotensin II[15]. These mechanisms contribute to increased glomerular perfusion, increased intraglomerular pressure, and glomerular hyperfiltration.

Regarding inflammatory responses, experimental and clinical evidence demonstrated changes in circulating leukocytes that may induce alterations in the levels of specific pro-inflammatory molecules[16]. Accordingly, increased expressions of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors have been observed in kidney biopsies from patients with DKD[17].

Instead, what concerns oxidative stress, hyperglycemia leads to the production of reactive oxygen species, which activates inflammasomes and induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and apoptosis, thus contributing to the progression of kidney damage[18-20].

Recent mechanistic models highlight the importance of chronic subclinical inflammation as a key promoter of kidney injury in diabetes[21,22]. Indeed, inflammation may constitute a link between biochemical stimuli, immune cell recruitment, oxidative stress, and renal cell alterations, ultimately leading to glomerular and vascular damage with interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy[23,24].

Moreover, several individual and demographic factors may influence the development, presentation, and natural history of DKD. For example, epidemiological studies have shown that DKD occurs more frequently in African Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans than in Caucasians[25]. These differences may be explained by genetic backgrounds and economic and social factors.

Less consistent data are available on the effects of sex on DKD. While sexual dysmorphism may influence the metabolic and molecular mechanisms underlying DKD, the extent of these effects and the characterization of high-risk subjects (men and pre-or postmenopausal women) remain under debate[26].

Estimating the incidence and prevalence of CKD and kidney failure in patients with DM is challenging because kidney biopsies are infrequently performed[27,28]. Indeed, patients with a long history of DM who present with albuminuria and/or a reduced eGFR are presumed to have DKD without histological confirmation.

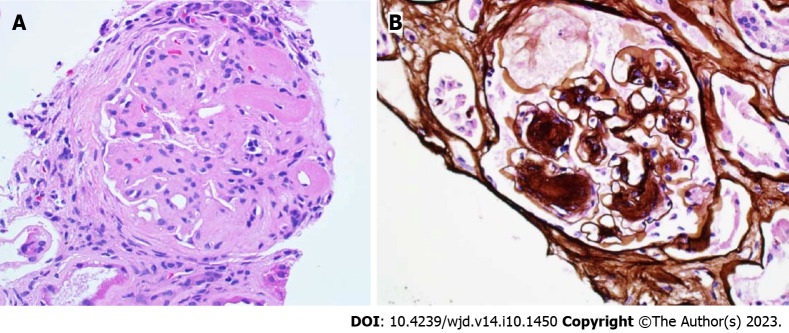

Currently, only a complete examination of the kidney biopsy may lead to the accurate definition of DKD versus NDKD[29]. The histological picture of DKD may vary, with pathological alterations in glomeruli, renal tubular cells, and vascular tissue[30]. The initial alteration in classical diabetic glomerulopathy is the thickening of the glomerular basement membrane[31]. Other glomerular changes include mesangial expansion, which can be diffuse or nodular (often termed “Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules”), podocyte injury, and glomerular sclerosis[32,33] (Figure (Figure1).1). A substantial number of patients with type 2 diabetes and DKD have mild or no glomerulopathy, with tubulointerstitial and/or arteriolar abnormalities[34,35]. Tubulointerstitial fibrosis usually occurs after the initial glomerular lesions and is the final pathway mediating progression to advanced CKD and ESKD. Patients with type 1 DM (T1DM) predominantly develop classical diabetic glomerulopathy, whereas pathological abnormalities in type 1 DM (T2DM), particularly in patients without albuminuria, are more heterogeneous[34,36,37].

Pure diabetic glomerulopathy. A: The glomerulus shows nodular expansion of the mesangial matrix and segmental sclerosis with hyalinosis (H&E 40 ×); B: Nodular mesangial matrix expansion with peripheralized capillaries (Jones methenamine silver 40 ×).

The heterogeneity of DKD is also clinically evident. Some differences between T1DM and T2DM are as follows: The former generally presents more conspicuously, while T2DM can be asymptomatic for years before diagnosis. The most common clinical features are persistently elevated urine albumin excretion (defined as a urine albumin excretion > 30 mg/d or > 30 mg/g) and persistently decreased eGFR (defined as an eGFR < 60 mL/min using a creatinine-based formula). In severe cases, albumin levels can exceed the nephrotic threshold of 3.5 g per 24 h, resulting in nephrotic syndrome[38,39].

The early phases of DKD are often asymptomatic; thus, manifestations are detected through routine testing. Therefore, patients with DM should undergo annual testing for kidney complications using the serum creatinine-based estimated glomerular eGFR and urine tests for abnormal levels of albumin excretion[40,41]. The urine sediment in DKD is usually bland; however, patients with severely increased albuminuria may have microscopic hematuria[42,43], and those with nephrotic-range proteinuria often have oval fat bodies or lipid droplets. Dysmorphic red blood cells and red blood cell casts are uncommon in patients with DKD and, if present, may suggest NDKD[44].

In addition to the classical phenotype of albuminuria with or without eGFR reduction, clinical experience and epidemiological studies have observed an increased incidence of reduced eGFR without albuminuria[45,46]. Being aware of this occurrence is necessary as the non-albuminuric phenotype is present in both T1DM and T2DM patients and includes patients progressing toward ESKD independently of developing albuminuria[47,48].

From a prognostic point of view, whether the natural history and rate of progression of DKD differ according to DM type remains unclear. In T2DM, disease onset usually occurs after the age of 40 years, and factors such as age-related senescence of the kidney and hypertension can contribute to the decline in kidney function to varying degrees. In addition, T2DM can be asymptomatic for years, which could lead to delayed diagnosis; therefore, the true time of onset of hyperglycemia is usually unknown[48,49]. Moreover, owing to the obesity pandemic[50], T2DM is progressively increasing compared with T1DM among youths, resulting in earlier development of complications, including CKD[51-53].

NDKD

NDKD includes various renal diseases diagnosed in patients with diabetes who may benefit from specific therapies. Therefore, distinguishing between DKD and NDKD is of paramount relevance because their prognosis and treatment differ.

However, the epidemiology of DKD and NDKD remains unclear. The reported prevalence of DKD and NDKD varies among centers regarding indications for renal biopsy in patients with diabetes[54]. Selection bias is possible for two reasons. First, the prevalence of NDKD may be overestimated, as the criteria for kidney biopsy are generally represented by an atypical presentation with clinical elements highly suggestive of NDKD. Second, because diabetic patients with CKD are often clinically diagnosed with DKD, the diagnosis of NDKD or NDKD superimposed on DKD is often missed[3].

In 328 patients with T2DM enrolled between 2001 and 2014, Li et al[55] identified a histological diagnosis of pure DKD in 57.3%, NDKD in 36.9%, and mixed forms in 5.8% of cases. Similarly, Zeng et al[56] observed the diagnosis of DKD in 48.4% out of 244 patients with T2DM. The diagnoses of NDKD and a mixed form were made in 45.9 and 5.7% of the patients, respectively. In 2017, in a meta-analysis of 48 studies, Fiorentino et al[27] found that the prevalence of DKD, NDKD, and overlapping forms was extremely variable, ranging from 6.5 to 94%, 3.0 to 82.9%, and 4.0 to 45.5%, respectively. More recently, Tong et al[57] found prevalence of 41.3% for DKD, 40.6% for NDKD, and 18.1% for mixed forms.

While the prevalence of DKD exceeded that of NDKD in Europe and Oceania, NDKD was more prevalent in North America, Asia, and Africa[57].

The pathological entities diagnosed on the kidney biopsies of patients with NDKD may also be influenced by ethnic and epidemiological factors. For example, while focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was the most prevalent diagnosis among patients in a North American cohort study, membranous nephropathy (MN) represented the most common pathological type of NDKD in Asia, Africa, and Europe[58].

Furthermore, it should be highlighted that patients affected by DM may also be at high risk of developing rare glomerulopathies, such as IgA-dominant acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis (APIGN). This is a subtype of APIGN first reported in the early 2000s and characterized by specific clinical and pathological elements[59]. From a clinical perspective, patients with IgA-dominant APIGN usually have severe and rapidly progressive renal failure with various degrees of hematuria, proteinuria, hypocomplementemia, and ongoing or recent staphylococcal infections. Patients with DM have a high prevalence of staphylococcal skin infections, which explains why DM is a major risk factor for glomerulonephritis[60,61].

Moreover, mounting evidence suggests that the intravitreal injection of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors used to treat diabetic retinopathy (DR) may be associated with glomerular diseases. Once injected intravitreally, VEGF inhibitors are systemically absorbed, leading to nephrotoxicity in podocytes and endothelial cells[62,63].

Finally, even when a kidney biopsy shows NDKD, the coexistence of DM could impact its presentation, management, and prognosis. In a cohort of patients with various glomerular diseases, Freeman et al[64] found that patients with versus without diabetes had a significantly higher rate of proteinuria and a higher rate of progression to ESKD regardless of diagnosis.

However, despite the potentially high clinical impact of these conditions, beyond some epidemiological findings, no prospective data are available. This is the rationale for designing CureGN-Diabetes, an ongoing multicenter prospective cohort study that aims to understand how diabetes influences the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of glomerular disease[65].

WHAT ELEMENTS MAY GUIDE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS BETWEEN DKD AND NDKD?

The clinical and histological heterogeneity of kidney damage in patients with diabetes highlights the importance of a proper differential diagnosis of DKD and NDKD. A correct diagnosis may impact clinical and therapeutic management. Even if some measures, such as optimizing glycemic and blood pressure control, and prescribing renin-angiotensin system inhibitors are strictly recommended for all diabetic patients with kidney disease, other treatments may differ significantly according to the diagnosis[66].

The main example is provided by immunosuppressive drugs (e.g., steroids, mycophenolate, cyclosporine, etc.), which are not indicated for DKD; otherwise, they may constitute the treatment of choice for patients with non-diabetes-related glomerular disease. In this case, the histological diagnosis of NDKD is essential to support the use of these drugs, considering their potential side effects, such as infections, leukopenia, and metabolic alterations[67].

Moreover, distinguishing between DKD and NDKD may affect long-term clinical management. Some forms of glomerular disease may recur after kidney transplantation[68]. Therefore, for diabetic patients who develop ESKD, it may be useful to determine the exact cause of kidney disease.

Given these considerations, many authors have attempted to characterize the most relevant factors for differentiating between DKD and NDKD (Table (Table11).

Table 1

Elements for the differential diagnosis between diabetic kidney disease and nondiabetic kidney disease

|

|

DKD

|

NDKD

|

Ref.

|

| Clinical characteristics | [57,71,72] | ||

| Diabetic retinopathy | Microhematuria; active urinary sediment | ||

| Longer diabetes duration (> 5 yr) | Acute onset of nephrotic proteinuria | ||

| Acute kidney injury | |||

| Positive autoimmunity | |||

| Histopathological elements | [27,29] | ||

| Light microscopy | |||

| Diffuse glomerulosclerosis | Thickening of the GBM; mesangial expansion; mesangiolysis | Reduced vascular involvement and arteriolar hyalinosis | |

| Nodular glomerulosclerosis | Mesangial expansion with nodular glomerular sclerosis (“Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules”) | ||

| Nodules are PAS-positive, silver and Congo red negative | Amyloidosis: Congo red positive staining | ||

| Immunofluorescence | Linear staining of the GBM and tubular basement membrane for IgG and albumin; no other specific stainings | MIDD: Light-chain and/or heavy-chain deposits; IgAN: Predominant or codominant mesangial staining for IgA with or without C3; Cryoglobulinaemia and MPGN: Mesangial and GBM staining for IgM, IgG and C3 | |

| Electron microscopy | Diffuse GBM thickening; diabetic fibrillosis; podocytopenia | Fibrillar and Immunotactoid glomerulonephritis: Microfibrillar and microtubules deposition; cryoglobulinaemia and MPGN: Mesangial, subendothelial and subepithelial electron-dense deposits, intracapillary thrombi and leucocytic infiltrate | |

| Radiological features | Higher renal arterial resistance index (> 0.66) | [78] | |

| Biomarkers | Higher uNGAL/creatinine ratio (cutoff = 60.85 ng/mg) | [75] | |

| Omic sciences | Specific biomolecular signatures in urine and plasma; proteomic analysis of extracellular vesicles | [79,80,81,83] | |

| Other techniques | Evaluation of urine samples by Raman spectroscopy and chemometric analysis | [82] | |

DKD: Diabetic kidney disease; NDKD: Nondiabetic kidney disease; MIDD: Monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disorder; IgAN: IgA nephropathy; GBM: Glomerular basal membrane; MPGN: Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; uNGAL: Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Currently, the most widely used approaches in clinical practice are based on evaluating clinical elements and histological findings.

The main clinical elements guiding the differential diagnosis are DM duration (shorter duration is more consistent with NDKD), microhematuria as a clinical indicator of NDKD, and evidence of DR as a clinical predictor of DKD[69]. Indeed, available data suggest that the absence of DR may predict NDKD; however, DKD cannot be excluded, whereas DR may occur in patients with mixed forms[70]. Moreover, a history of poor glycemic and blood pressure control is another factor that orients DKD[71,72]. Regarding the clinical presentation, rapid-onset severe albuminuria and/or a rapid eGFR decline (sometimes presenting as acute kidney injury), such as active urinary sediment, should be considered possible alternative etiologies.

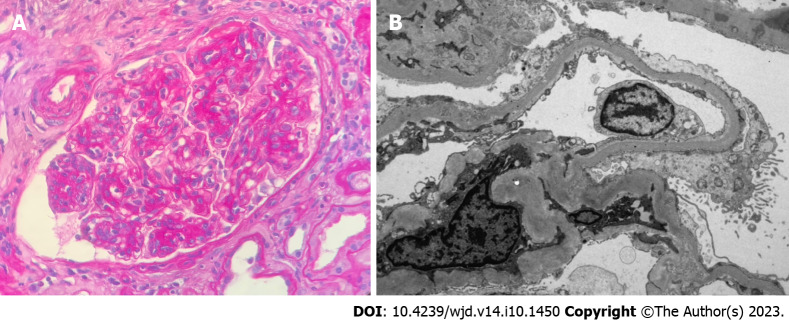

Given the clinical limitations of reaching a proper diagnosis, renal biopsy remains an essential tool for differential diagnosis. However, even if a renal biopsy is performed, drawing a definite conclusion is not always straightforward. As mentioned previously, glomerulopathies may overlap with DKD. Moreover, some diseases may exhibit histological features resembling those of DKD. For example, both diffuse and nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis are common diseases; in these cases, immunofluorescence and thorough ultrastructural examination using electron microscopy is required[30]. Diffuse diabetic glomerulosclerosis includes the differential diagnosis of IgAN, MN, and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (Figure (Figure2).2). Alsaad et al[29] emphasized that these glomerulopathies frequently exhibit reduced vascular involvement and less severe arteriolar hyalinosis than diabetic nephropathy. Nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis poses great concerns in terms of its differential diagnosis. For example, as their appearance on light microscopy may overlap, amyloidosis may only be distinguished from DKD by red-positive Congo staining, while non-amyloidotic monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disease presents a typical light-chain and/or heavy-chain deposition on immunofluorescence. Fibrillar and immunotactoid glomerulonephritis may have various histological patterns, including nodular glomerulosclerosis, and when these entities are suspected, diagnostic certainty is obtained only with ultrastructural evaluation using electron microscopy. The most challenging differential diagnosis is idiopathic nodular glomerulosclerosis, a rare glomerulopathy that is not histologically distinguishable from nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis. In this case, the absence of DM was the only diagnostic element[30]. While kidney biopsy remains the gold standard method to obtain a differential diagnosis between DKD and NDKD, an advancement in precision medicine in the renal setting is the definition of novel noninvasive biomarkers[73]. Many studies have evaluated different molecules, such as urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), plasma copeptin, urinary liver-type fatty acid-binding protein, and, more recently, the omics platform-based approach, finding that these molecules may be correlated with kidney disease progression[74]. As tubulointerstitial involvement occurs frequently in DKD, some authors have attempted to clarify the role in the differential diagnosis between DKD and NDKD[75] of NGAL, a well-known tubulointerstitial biomarker[76,77]. Duan et al[75] recruited 100 patients with T2DM who were histologically diagnosed with DKD (n = 79) or NDKD (n = 21). Urinary NGAL levels were normalized to creatinine levels to obtain the uNGAL/creatinine ratio (uNCR). The uNCR was an independent risk factor for DKD in patients with DM and renal impairment, and patients with NDKD showed lower uNCR levels than patients with DKD. A uNCR value of 60.685 ng/mg was found as the best predictive cutoff for DKD. Interestingly, patients with DKD with a uNCR higher than 60.685 ng/mg showed a worse prognosis and a higher risk of developing proteinuria in the nephrotic range[75].

Nondiabetic kidney disease. A: Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis and diabetic nephropathy. Lobulated glomerulus due to nodular mesangial expansion and endocapillary hypercellularity in a patient with diabetes and proliferative glomerulopathy with monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition (PAS 40 ×); B: Severe effacement of the foot processes over thickened glomerular basement membranes in a patient with diabetic glomerulosclerosis with superimposed podocyte injury (electron microscopy, magnification 2000 ×).

Confirming the vascular involvement in diabetic nephropathy, Li et al[78] described a higher renal arterial resistance index (RI) in patients with DKD than in patients with NDKD, with 0.66 being the optimal predictive cutoff for DKD, even after adjusting for serum creatinine levels. The authors also created a promising diagnostic tool: A RI-based prediction model for the differential diagnosis between DKD and NDKD.

Interestingly, some innovative solutions to early and proper diagnosis of kidney involvement in diabetic patients come from studies using omics sciences. The proteomic analysis of the urine (nowadays seen as a potential surrogate for the kidney biopsy) by multiple peptide panels, such as cell-free microRNAs and extracellular vesicles, has allowed to predict DKD development and progression[79-81].

In addition, very recently, it has been demonstrated that the evaluation of urine samples by Raman spectroscopy followed by chemometric analysis may be able to differentiate between DKD and NDKD with high specificity and sensitivity[82]. Similar results were also found in blood samples, in which the combination of traditional molecular biology and transcriptomic approaches has led to the identification of potential DKD biomarkers[83,84].

While these new approaches may improve the risk stratification of patients with diabetes and kidney disease, they have scarcely been studied in clinical trials[85].

Thus, although integrating biomarkers into the clinical management of patients with diabetes seems promising, the effective use of these tools remains to be defined, and longitudinal prospective studies are needed to validate these strategies.

HOW CAN THE TREATMENT OF KIDNEY DISEASES IMPACT GLYCEMIC CONTROL?

One of the least considered aspects of the relationship between DM and kidney disease is the possibility of developing DM during the treatment of glomerular diseases.

Although post-transplant DM has been the subject of extensive clinical and experimental research, data on epidemiology, pathogenesis, and risk factors of new-onset DM among patients with glomerular diseases (NODAG) are scarce[86].

Conversely, conceivable data extrapolated from transplant studies may not apply to patients with glomerulonephritis as immunosuppressive strategies in these patient populations are substantially different in terms of intensity and duration of treatment. Theoretically, patients with glomerular diseases may present with multiple causes for the development of DM and metabolic complications. Renal diseases, particularly inflammation, are associated with reduced glucose filtration, increased insulin resistance, hyperuricemia, and impaired tubular function, which predispose patients to hyperglycemia[87]. Moreover, all the immunosuppressive drugs commonly used to treat glomerulonephritis may cause metabolic complications[88]. Apart from the well-known hyperglycemic effects of corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus, may promote DM through a direct effect on pancreatic β-islet cells[89]. Given these considerations, the scarcity of data regarding this issue is surprising. In 2017, Miyawaki et al[90] investigated the incidence of new-onset DM in a cohort of 95 patients at the first diagnosis of IgAN treated with tonsillectomy combined with steroid pulse therapy and evaluated them both during hospitalization and after 1 year of follow-up.

They found that DM occurred with an incidence of 20% (19 patients) only during the hospitalization, and no patients developed DM during the follow-up. Patients developing NODAG, compared with patients without DM, were older, with a higher prevalence of hypertension and family history of DM. In addition to steroid use, age and family history of DM have emerged as independent risk factors for DM development.

Lim et al[91] evaluated the epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes of NODAG in 448 Asian patients with biopsy-proven glomerulonephritis. Among the evaluated patients, the most common diagnoses were lupus nephritis (24.6%), MCD, FSGS (27.7%), and IgAN (21.7%). The majority (72.1%) received immunosuppressants after diagnosis, mostly steroids, mycophenolate, cyclosporine, and cyclophosphamide. Moreover, patients also received non-immunosuppressant drugs such as diuretics and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. NODAG occurred in 48 patients (10.7%); the time from biopsy to hyperglycemia was 9.1 wk. Methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide are commonly administered to patients with NODAG. Hyperlipidemia, greater proteinuria, lower HDL-C levels, and methylprednisolone use were independently associated with NODAG risk. Looking at clinical outcomes, the authors noticed no differences in ESKD, time to ESKD, cardiovascular disease, or death among patients with NODAG compared with those who did not develop it. In 2020, the same group evaluated the prevalence of prediabetes and NODAG in a cohort of 229 nondiabetic adults diagnosed with glomerulonephritis[92]. The authors found that prediabetes was already present in approximately one-third of patients at the time of renal biopsy. After the biopsy and during the follow-up, 29 patients (12.7%) developed NODAG. Adjusted multivariate analysis confirmed that prediabetes and methylprednisolone use were independently associated with NODAG.

Overall, these data highlight that new-onset DM after the diagnosis of the glomerular disease is an early event with a significant incidence ranging from approximately 10% to 20% of glomerular patients. This variability may be due to the intensity of the immunosuppressive treatment and use of corticosteroids.

MAY ANTIDIABETIC DRUGS INFLUENCE THE COURSE OF KIDNEY DISEASES? THE EXAMPLE OF SGLT2 INHIBITION

Recent evidence suggests that novel antidiabetic drugs may exert significant nephroprotective effects resulting in a reduction of albuminuria and a slower decline in eGFR in patients with CKD, even in the absence of diabetes[93]. An example is provided by the case of SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), recently introduced to the market.

In the kidneys, the reabsorption of filtered glucose occurs through SGLTs, a family of membrane proteins expressed in the renal proximal tubule. SGLT2, a high-capacity, low-affinity transporter, accounts for approximately 90% of glucose reabsorption in the kidneys. Thus, the pharmacological inhibition of SGLT2 may reduce glucose and sodium reabsorption by inducing glycosuria[94]. This mechanism of action offers potential promise for the treatment of patients with T2DM; consequently, early research focused on the effects of SGLT2i in improving glucose control and metabolic parameters[95]. However, in recent years, SGLT2i have arisen from antidiabetic drugs to cardiorenal protective treatments. The first trials exploring the cardiovascular effects of SGLT2i were EMPA-REG OUTCOME, testing empagliflozin; CANVAS, testing canagliflozin; and DECLARE-TIMI 58, testing dapagliflozin[96-98]. Briefly, these trials showed that in patients with T2DM, the addition of SGLT2i to standard care reduced the incidence of cardiovascular events and mortality. Interestingly, although not specifically designed to the scope, both secondary and post-hoc analyses in subgroups of patients with CKD showed that SGLT2i treatment was correlated with a slower progression of kidney disease and a reduced number of renal events, defined as increased proteinuria, eGFR reduction, ESKD, or death from renal disease[99].

Theoretically, several plausible mechanisms of action for SGLT2i are present in the kidneys[100]. The first effect is lowering the threshold for glucose excretion, normally 180 mg/dl to approximately 40 mg/dl, causing glycosuria and consequently reducing serum glycemia and HbA1c (0.6%-1.0%) and improving insulin secretion and sensitivity. However, other factors may be implicated. For example, limiting the passage of glucose through proximal cells can reduce glycolysis, which can be related to renal fibrosis[101]. The reabsorption of glucose is coupled with Na+ in the proximal tubule; inhibition of SGLT2 leads to increased delivery of NaCl to the macula densa, activating tubule-glomerular feedback and reducing intraglomerular pressure[102]. Moreover, this mechanism, associated with decreased activity of the Na+-H+ antiporter, may exert a natriuretic effect with a subsequent reduction in blood pressure and hypervolemia. Previous effects allow SLGT2i to reduce kidney ATP consumption and prevent kidney hypoxia. Other effects are being studied, such as the possibility of weakening fibrosis, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and podocyte loss, stimulating uricuria and autophagy, and improving metabolic flexibility and weight loss[103,104]. Based on these considerations and the results of early trials, additional studies have been specifically designed to test the renal effects of SGLT2i in patients with kidney disease with or without DM. The CREDENCE trial (canagliflozin), which included only patients with T2DM with an eGFR of 30-90 mL/min and albuminuria, showed that patients with kidney disease who received canagliflozin had a lower risk of death from renal or cardiovascular causes, ESKD, or doubling of the serum creatinine level than those who received a placebo[105]. Instead, in the DAPA-CKD enrolling patients with eGFR 25-75 mL/min and albuminuria > 200 mg/g, approximately one-third of the patients had no prior DM. In this cohort, the diagnoses of kidney diseases included IgAN in 17%, FSGS in 2%, MN, and other glomerular diseases. Nonetheless, even in patients affected by T2DM, approximately 3% of patients with coexistent GN exist (1% IgAN, 1% FSGS, < 1% MN)[106]. In addition to the renal protective effects of dapagliflozin reported in the entire study population, sub-analyses were performed on 270 patients with IgAN and 104 patients with FSGS. These studies indicated that while dapagliflozin was effective in slowing kidney disease progression in IgAN, in patients with FSGS, the reduction in eGFR decline was not statistically significant compared with the placebo[107,108]. Finally, in the more recent EMPA-KIDNEY trial enrolling patients with eGFR > 20 mL/min with or without albuminuria, only 46% of the patients had a history of DM, including 6% of patients with a biopsy-proven concomitant glomerular disease (3% IgAN). In 54% of the patients without DM, the most prevalent diagnosis was IgAN (21%) and FSGS (5%)[109]. In agreement with previous results, in this trial, the use of an SGLT2i, empagliflozin, was associated with significant clinical benefits in renal outcomes regardless of basal eGFR and the presence/absence of DM. The importance of this evidence is highlighted by the fact that the European Medicines Agency recently approved the first SGLT2i, dapagliflozin, as a nephroprotective drug for the treatment of CKD in nondiabetic patients[110].

Plausibly, in the future, this indication will be expanded to other molecules in the SGLT2i class and patients affected by systemic diseases, such as erythematous systemic lupus and vasculitis, who were excluded from all large renal outcome trials[111].

The development and clinical application of sGLT2i offer just an example of successful translational research, underlying how the individuation of new molecular mechanisms linking kidney disease and diabetes.

Similar considerations could be made for other antidiabetic drugs, such as metformin and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, that have shown nephroprotective effects[93,112,113]. However, research on the pathogenesis of DM and kidney damage is an extremely active field[114]. So, both experimental findings and clinical scenarios of kidney disease in diabetes are rapidly evolving, and significant innovations are expected in the next future.

CONCLUSION

Here, we overviewed the complex bidirectional relationship between diabetes and renal disease. Regarding kidney involvement in patients with diabetes, we underline the necessity of an appropriate diagnostic workup to define a precise diagnosis, as many conditions other than DKD may cause renal impairment. Accurate diagnosis has important clinical implications and may guide therapeutic approaches.

In this view, although the potential utility of new biomarkers, kidney biopsy remains an irreplaceable tool for acquiring crucial information on the diagnosis and severity of renal damage. Furthermore, we discuss the risk of developing new-onset DM as a complication of immunosuppressive treatment in patients with immune-mediated renal disease. Available data reveal that about 10%-20% of patients treated for glomerulonephritis may develop DM, but it is unclear if de-novo DM may affect renal or general outcomes. Therefore, while waiting for proper longitudinal prospective studies, it appears reasonable to devote more attention to the early recognition of DM in patients with glomerular diseases.

Finally, the case of SGLT2i, first tested as an antidiabetic drug and then showing glucose-independent nephroprotective effects, suggests that both experimental and clinical research may have practical implications. This example demonstrates how efforts to improve our understanding of the complex pathophysiology of diabetes and kidney diseases may translate into novel therapeutic approaches[115].

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: June 21, 2023

First decision: July 28, 2023

Article in press: August 28, 2023

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hu X, China; Tazegul G, Turkey; Zhao W, China; Horowitz M, Australia S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

Contributor Information

Pasquale Esposito, Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties (DiMI), University of Genoa, Genoa 16132, Italy. Unit of Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa 16132, Italy. [email protected].

Daniela Picciotto, Unit of Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa 16132, Italy.

Francesca Cappadona, Unit of Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa 16132, Italy.

Francesca Costigliolo, Unit of Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa 16132, Italy.

Elisa Russo, Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties (DiMI), University of Genoa, Genoa 16132, Italy. Unit of Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa 16132, Italy.

Lucia Macciò, Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties (DiMI), University of Genoa, Genoa 16132, Italy.

Francesca Viazzi, Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties (DiMI), University of Genoa, Genoa 16132, Italy. Unit of Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa 16132, Italy.

References

Articles from World Journal of Diabetes are provided here courtesy of Baishideng Publishing Group Inc

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Application of a validated prognostic plasma protein biomarker test for renal decline in type 2 diabetes to type 1 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II.

Clin Diabetes Endocrinol, 10(1):30, 10 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39385270 | PMCID: PMC11466018

The effect of long-term hemodialysis on diabetic retinopathy observed by swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography.

BMC Ophthalmol, 24(1):334, 09 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39123172 | PMCID: PMC11316430

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Renal pathology patterns in type II diabetes mellitus: relationship with retinopathy. The Collaborative Study Group.

Nephrol Dial Transplant, 13(10):2547-2552, 01 Oct 1998

Cited by: 89 articles | PMID: 9794557

Glomerular Diseases in Diabetic Patients: Implications for Diagnosis and Management.

J Clin Med, 10(9):1855, 24 Apr 2021

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 33923227 | PMCID: PMC8123132

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Pathologic classification of diabetic nephropathy.

J Am Soc Nephrol, 21(4):556-563, 18 Feb 2010

Cited by: 764 articles | PMID: 20167701