Abstract

Free full text

Endothelial cells regulate alveolar morphogenesis by constructing basement membranes acting as a scaffold for myofibroblasts

Abstract

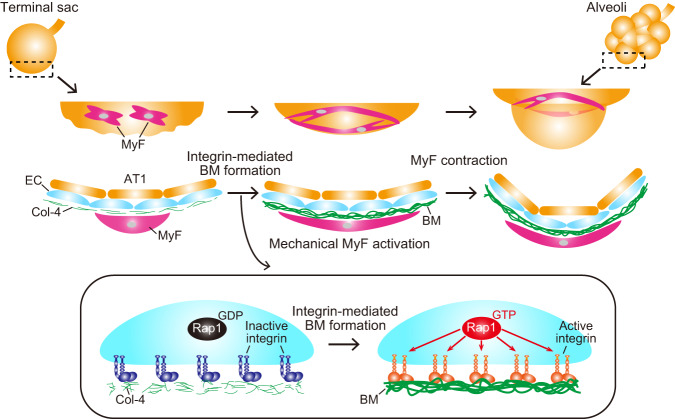

Alveologenesis is a spatially coordinated morphogenetic event, during which alveolar myofibroblasts surround the terminal sacs constructed by epithelial cells and endothelial cells (ECs), then contract to form secondary septa to generate alveoli in the lungs. Recent studies have demonstrated the important role of alveolar ECs in this morphogenetic event. However, the mechanisms underlying EC-mediated alveologenesis remain unknown. Herein, we show that ECs regulate alveologenesis by constructing basement membranes (BMs) acting as a scaffold for myofibroblasts to induce septa formation through activating mechanical signaling. Rap1, a small GTPase of the Ras superfamily, is known to stimulate integrin-mediated cell adhesions. EC-specific Rap1-deficient (Rap1iECKO) mice exhibit impaired septa formation and hypo-alveolarization due to the decreased mechanical signaling in myofibroblasts. In Rap1iECKO mice, ECs fail to stimulate integrin β1 to recruit Collagen type IV (Col-4) into BMs required for myofibroblast-mediated septa formation. Consistently, EC-specific integrin β1-deficient mice show hypo-alveolarization, defective mechanical signaling in myofibroblasts, and disorganized BMs. These data demonstrate that alveolar ECs promote integrin β1-mediated Col-4 recruitment in a Rap1-dependent manner, thereby constructing BMs acting as a scaffold for myofibroblasts to induce mechanical signal-mediated alveologenesis. Thus, this study unveils a mechanism of organ morphogenesis mediated by ECs through intrinsic functions.

Introduction

Alveologenesis is the final step of lung development aimed at generating alveoli, creating a large surface area for gas exchange between the lungs and blood. In mice, alveologenesis starts after birth and continues for several weeks, ultimately giving rise to more than 2 million alveoli. Alveolar formation is a spatially coordinated morphogenetic event regulated by multiple cell types such as alveolar epithelial type I (AT1) and type II (AT2) cells, myofibroblasts, endothelial cells (ECs), pericytes, and autonomic neurons1–4. During alveologenesis, the walls of terminal sacs at the ends of the respiratory bronchioles protrude into the air space to form secondary septa, which subdivide at the terminal sac to generate alveoli. Two-dimensional (2D) analysis of terminal sacs revealed that myofibroblasts exist at the tip of a growing secondary septum. Furthermore, a reduction of myofibroblasts or their specific ablation in mice reportedly prevented alveolar formation5–8. Thus, myofibroblasts are regarded as a key player in secondary septa formation. Importantly, Sun’s group, by performing 3D imaging analysis of alveolar morphogenesis, showed that thinly stretched and long myofibroblasts surround the alveolar entry rings and contract against air pressure on the alveolar wall to induce the formation of secondary septa9. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that myofibroblast contraction required for septa formation depends on insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor-stimulated mechanical signaling that involves myosin light chain kinase (MLCK)-mediated activation of myosin and nuclear localization of Yes-associated protein (YAP), an effector of the Hippo pathway10,11.

ECs not only form blood vessel networks for delivering blood but also produce paracrine cues referred to as angiocrine factors, which actively regulate the development, maintenance and regeneration of various organs, the self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells, and even underlie the pathogenesis of many diseases such as tissue fibrosis and tumor progression12–14. Indeed, pulmonary EC-derived angiocrine factors were shown to regulate lung development and regeneration. EC-derived hepatocyte growth factor stimulates epithelial cells to induce primary septa formation during distal lung morphogenesis15. Previous reports also showed that upon pneumonectomy, pulmonary ECs promote the proliferation of alveolar epithelial cells and bronchioalveolar stem cells (BASCs) by releasing matrix metalloproteinase 14 to increase the bioavailability of EGF ligands16,17. Furthermore, during lung regeneration, BASCs were shown to be specified into alveolar epithelial cells by thrombospondin-1 produced by pulmonary ECs18. In addition, several studies have clearly shown the essential role of pulmonary ECs in alveologenesis. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling after birth decreases alveolarization possibly through prevention of angiogenesis19,20. Furthermore, mice lacking platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM1) reportedly exhibit impaired alveologenesis, pointing to an active role of ECs in alveolarization21. Importantly, a recent study demonstrated that loss of aerocytes (aCap), alveolar capillary ECs specialized for gas exchange, resulted in hypo-alveolarization despite normal differentiation of myofibroblasts22. These results suggest that pulmonary ECs regulate alveolar morphogenesis independently of inducing myofibroblast differentiation. However, the mechanism underlying EC-mediated alveologenesis is still not fully understood.

Herein, we analyzed EC-specific Rap1a/Rap1b double knockout mice and uncovered a molecular mechanism governing the regulation of alveolar morphogenesis by pulmonary ECs. Rap1, a small GTPase belonging to the Ras superfamily, is known to potentiate both integrin-mediated cell adhesions into the extracellular matrix and cadherin-mediated cell-cell junctions23–27. Mammalian genomes encode two highly homologous and evolutionarily conserved Rap1 genes, Rap1a and Rap1b. We found that postnatal deletion of endothelial Rap1a and Rap1b resulted in impairment of mechanical signaling in alveolar myofibroblasts characterized by compromised alveologenesis. The link between endothelial Rap1 and mechanical activation of alveolar myofibroblasts is mediated via endothelial Rap1 stimulation of integrin β1, which in turn induces the formation of basement membranes (BMs) that act as a scaffold for myofibroblasts and promote alveologenesis through mechanical signaling. Thus, this study unveils a mechanism of organ morphogenesis mediated by ECs, which affect myofibroblasts by assembling a BM rather than producing angiocrine factors.

Results

Rap1 is required for alveologenesis

To investigate the role of Rap1 in ECs during early postnatal stages, we generated mice lacking both Rap1a and Rap1b in ECs (Rap1iECKO) by crossing double-floxed Rap1a/b mice (Rap1fl/fl) with mice expressing CreERT2 recombinase under the control of the Cdh5 promoter and by delivering tamoxifen via the lactating mothers for three consecutive days from postnatal day 0 (P0) (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Rap1fl/fl mice without the CreERT2 gene served as a control. To ensure the specific ablation of Rap1a/b paralogs in the EC lineage, we isolated CD31 (also known as PECAM1)-positive [CD31(+)] ECs and platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα)-positive [PDGFRα(+)] cell populations including myofibroblasts from the lungs of P9 pups by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). CD31(+) and PDGFRα(+) cells were found to express the EC marker, Pecam1, and the myofibroblast marker, Eln, respectively, confirming sorting of the desired cell populations (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Importantly, expression levels of Rap1a and Rap1b mRNAs in CD31(+) cells derived from Rap1iECKO mice were significantly downregulated compared to those from Rap1fl/fl mice (Supplementary Fig. 1c). However, their expression was not altered in PDGFRα(+) cells regardless of genotypes, confirming EC-specific and efficient deletion of Rap1a and Rap1b genes in Rap1iECKO mice.

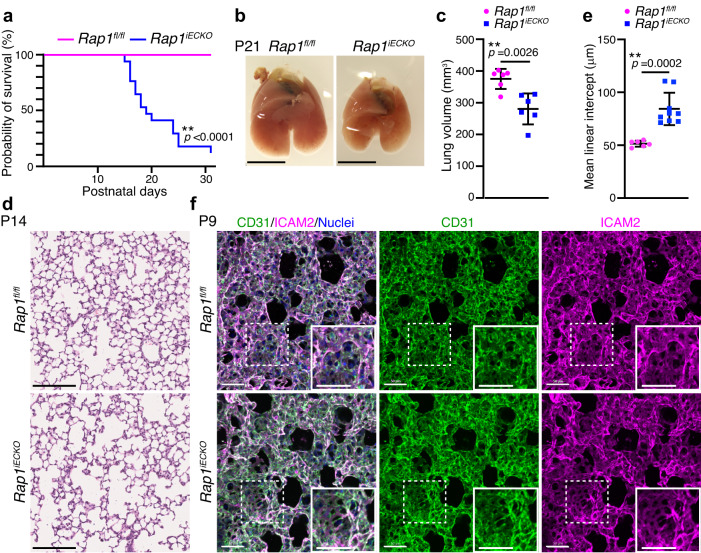

We analyzed Rap1iECKO mice and found that they exhibited postnatal lethality. Rap1iECKO mice started to die at P15 and more than 90% of the mutant mice were lost by P30 (Fig. 1a). When identifying the causes of death, we noticed that the lungs of Rap1iECKO mice were significantly smaller than those of controls at P21 (Fig. 1b, c). This difference in lung size was already apparent at P14, but not at P7, even though the body weights of control and Rap1iECKO mice were similar (Supplementary Fig. 1d, e). Furthermore, Rap1iECKO mice exhibited an increased mean linear intercept (MLI) of the lungs compared to control siblings at P14, but not at P7 (Fig. 1d, e and Supplementary Fig. 1f), indicating that postnatal alveologenesis is compromised in the absence of endothelial Rap1. On the other hand, tissue morphologies of the liver, stomach, and intestine appeared to be normal at P14 in Rap1iECKO mice, suggesting that the lung abnormality is not secondary to the systemic defects (Supplementary Fig. 1g).

a Kaplan–Meier survival curves for Rap1fl/fl (pink) and Rap1iECKO (blue) mice (n =

= 22 mice/each). b Representative images of the lungs from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P21. c Lung volumes of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P21. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Data are means

22 mice/each). b Representative images of the lungs from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P21. c Lung volumes of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P21. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Data are means ±

± s.d. (n

s.d. (n =

= 6 mice/each). d Representative images of HE-stained lung tissues from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P14. e Mean linear intercepts (MLI) in the lungs of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P14, as in (d). Each dot represents an individual mouse. Data are means

6 mice/each). d Representative images of HE-stained lung tissues from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P14. e Mean linear intercepts (MLI) in the lungs of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P14, as in (d). Each dot represents an individual mouse. Data are means ±

± s.d. (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n

s.d. (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n =

= 6 and 9 mice). f Confocal z-projection images for CD31 (green), ICAM2 (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli isolated from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9. Boxed areas are enlarged in the insets. **P

6 and 9 mice). f Confocal z-projection images for CD31 (green), ICAM2 (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli isolated from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9. Boxed areas are enlarged in the insets. **P <

< 0.01, by the log-rank test (a) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (c, e). Scale bars; 5

0.01, by the log-rank test (a) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (c, e). Scale bars; 5 mm (b), 250

mm (b), 250 μm (d), 50

μm (d), 50 μm (f). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

μm (f). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Next, we investigated whether defective alveologenesis in Rap1iECKO mice is attributable to abnormal development of the lung vasculature by performing 3D immunofluorescence analysis of lungs using anti-CD31 and anti-intercellular adhesion molecule 2 (ICAM2) antibodies. However, the alveolar vascular structure in Rap1iECKO mice at P4 and P9 was almost identical to that in control siblings (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1h). The alveolar capillary network is composed of two types of ECs, the aCap and the general capillary (gCap) ECs22. Staining of P14 lungs with antibodies for their specific marker carbonic anhydrase 4 (Car4) for aCap and plasmalemma vesicle-associated protein (PLVAP) for gCap showed that aCap and gCap ECs were in normal amounts and locations in the alveolar capillaries of Rap1iECKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 1i). Furthermore, staining of P9 lungs with antibodies for the Ets-related gene (ERG) (a marker of endothelial nuclei), for phosphorylated histone H3 (PHH3) (a proliferation marker), and for Cleaved-caspase3 (an apoptosis marker) revealed similar numbers of alveolar capillary ECs as well as the frequency of proliferation and apoptosis in P9 lungs of control and Rap1iECKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 1j–m). These results indicate that alveolar capillary networks develop normally in Rap1iECKO mice. Rap1 is known to potentiate endothelial barrier function by forming vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin-mediated EC-EC junctions24,28–30. However, Rap1iECKO mice did not exhibit vascular hemorrhage (Supplementary Fig. 1n), suggesting the barrier function of alveolar capillaries to be preserved in those mice. Collectively, our findings suggest that alveolar capillary ECs actively regulate alveolar morphogenesis in a Rap1-dependent manner.

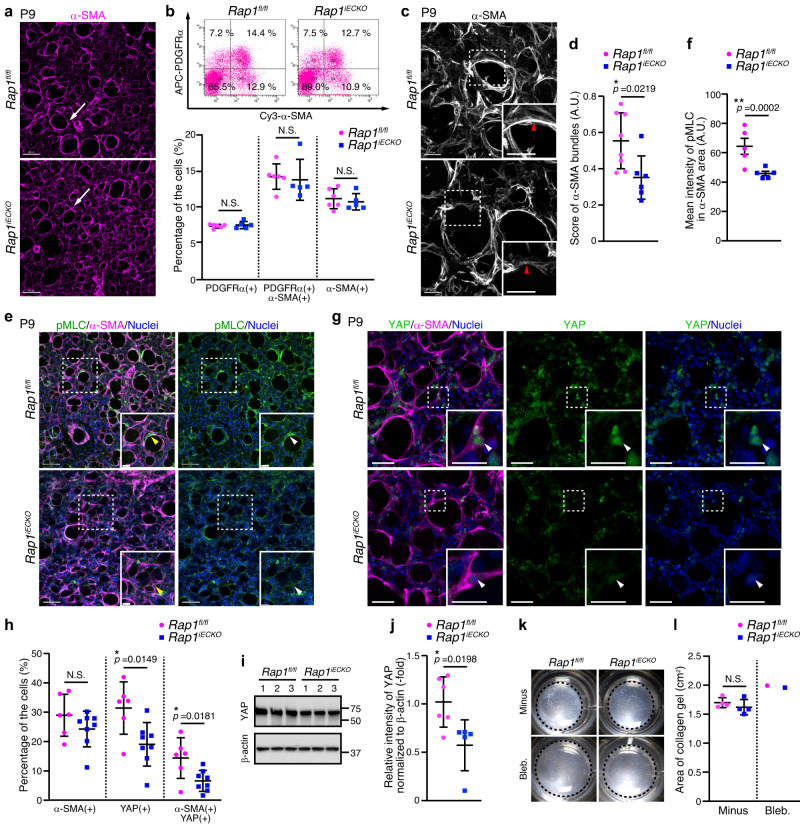

Rap1 regulates mechanical signaling required for alveolar myofibroblast contraction

Postnatal alveolar morphogenesis depends largely on the contractile force produced by alveolar myofibroblasts9. Hence, to investigate whether alveolar myofibroblast differentiation is affected in Rap1iECKO mice, we employed 3D immunostaining with a myofibroblast marker antibody [α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)] and found that myofibroblasts were present in terminal sacs at P4 and localized to the alveolar entry ring at P9 in both control and Rap1iECKO mice (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Consistently, autonomic nerves, which have recently been shown to regulate myofibroblast proliferation and migration4, developed normally in Rap1iECKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Flow cytometric analysis also revealed normal numbers of alveolar myofibroblasts [α-SMA(+)/PDGFRα(+) cells], myofibroblast progenitors [PDGFRα(+) cells], and smooth muscle cells [α-SMA(+) cells] in the lungs of Rap1iECKO mice (Fig. 2b). These findings indicate that myofibroblast differentiation occur normally in Rap1iECKO mice. We also found that the appearance of AT1 cells labeled with their marker antibody [Advanced Glycosylation End-Product Specific Receptor (RAGE)], did not differ between control and Rap1iECKO mice at either P4 or P9 (Supplementary Fig. 2c), revealing that AT1 cells are not involved in the impairment of alveologenesis in Rap1iECKO mice.

a Confocal z-projection images for α-SMA in alveoli from P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice. Arrowheads, myofibroblasts surrounding the alveolar entry ring. b Upper, flow cytometry plots of myofibroblasts [α-SMA(+)/PDGFRα(+) cells], their progenitors [PDGFRα(+) cells] and smooth muscle cells [α-SMA(+) cells] in the lungs of P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice. Plots show Cy3-anti-α-SMA versus APC-anti-PDGFRα fluorescence. Lower, percentages of cell populations as indicated at the bottom (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n =

= 6 and 5 mice). c Confocal z-projection images for α-SMA in alveoli from P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice. Arrowheads, α-SMA filaments. d Score of α-SMA bundles in alveoli (arbitrary units, A.U.), as in (c) (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n

6 and 5 mice). c Confocal z-projection images for α-SMA in alveoli from P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice. Arrowheads, α-SMA filaments. d Score of α-SMA bundles in alveoli (arbitrary units, A.U.), as in (c) (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n =

= 8 and 6 mice). e Confocal z-projection images for pMLC(S19) (green), α-SMA (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice. Arrowheads, pMLC signal in myofibroblasts. f pMLC fluorescence intensity in α-SMA(+) areas (arbitrary units, A.U.), as in (e) (n

8 and 6 mice). e Confocal z-projection images for pMLC(S19) (green), α-SMA (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice. Arrowheads, pMLC signal in myofibroblasts. f pMLC fluorescence intensity in α-SMA(+) areas (arbitrary units, A.U.), as in (e) (n =

= 5 mice/each). g Confocal z-projection images for YAP (green), α-SMA (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice. Arrowheads, the nuclei of α-SMA(+) myofibroblasts. h Percentages of α-SMA(+), nuclear YAP(+), α-SMA(+)/nuclear YAP(+) cell populations, as in (g) (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n

5 mice/each). g Confocal z-projection images for YAP (green), α-SMA (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice. Arrowheads, the nuclei of α-SMA(+) myofibroblasts. h Percentages of α-SMA(+), nuclear YAP(+), α-SMA(+)/nuclear YAP(+) cell populations, as in (g) (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n =

= 6 and 8 mice). i Western blot analysis of YAP and β-actin in lungs of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9 (3 mice/each). j, Expression levels of YAP relative to those of β-actin, as in i (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n

6 and 8 mice). i Western blot analysis of YAP and β-actin in lungs of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9 (3 mice/each). j, Expression levels of YAP relative to those of β-actin, as in i (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n =

= 6 and 5 mice). k Representative images of collagen gels containing PDGFRα(+) cells from the lungs of P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice and cultured without (Minus) or with 10

6 and 5 mice). k Representative images of collagen gels containing PDGFRα(+) cells from the lungs of P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice and cultured without (Minus) or with 10 μM blebbistatin (Bleb.). l, Quantification of collagen gel areas (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO without/with Bleb., n

μM blebbistatin (Bleb.). l, Quantification of collagen gel areas (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO without/with Bleb., n =

= 6/1 and 6/1 mice). Each dot represents an individual mouse, and data are presented as means

6/1 and 6/1 mice). Each dot represents an individual mouse, and data are presented as means ±

± s.d. (b, d, f, h, j, l). N.S., no significance; *P

s.d. (b, d, f, h, j, l). N.S., no significance; *P <

< 0.05 by two-tailed Student’s t-test (d, f, h, j, l). Boxed areas are enlarged in the insets (c, e, g). Scale bars; 80

0.05 by two-tailed Student’s t-test (d, f, h, j, l). Boxed areas are enlarged in the insets (c, e, g). Scale bars; 80 μm (a, e), 20

μm (a, e), 20 μm (c, g and enlarged in c and e), 10

μm (c, g and enlarged in c and e), 10 μm (enlarged in g). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

μm (enlarged in g). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

However, we observed the α-SMA filaments in myofibroblasts to be markedly thinner in Rap1iECKO mice than in controls (Fig. 2c, d and Supplementary Movie 1, 2), pointing to a functional impairment of myofibroblasts in Rap1iECKO mice. Alveolar myofibroblasts generate contractile force through activation of mechanical signaling involving MLCK-dependent phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC) and nuclear localization of YAP10,11. Therefore, to investigate whether mechanical signaling in alveolar myofibroblasts is affected in Rap1iECKO mice, we employed 3D immunostaining with antibodies against phosphorylated-myosin light chain (pMLC) and YAP. In control mice, myofibroblasts localized to the alveolar entry ring showed a strong pMLC signal (Fig. 2e, f). However, the pMLC signal in alveolar myofibroblasts of Rap1iECKO siblings was dramatically decreased. Furthermore, the number of alveolar myofibroblasts exhibiting the nuclear YAP signal in Rap1iECKO mice was also significantly lower than that in control mice (Fig. 2g, h). Cells other than myofibroblasts in the lungs of Rap1iECKO mice also tended to have a weak nuclear YAP signal. Consistently, YAP protein levels in the lungs of Rap1iECKO mice were lower than those in control mice, suggesting reduced nuclear YAP localization in the Rap1iECKO mice, since YAP retained in the cytoplasm undergoes proteasomal degradation31 (Fig. 2i, j). These findings indicate that mechanical signaling in alveolar myofibroblasts is impaired in Rap1iECKO mice.

Next, we investigated whether mechanical signaling in myofibroblasts of Rap1iECKO mice is compromised in a cell-autonomous or a non-cell-autonomous manner. To this end, PDGFRα(+) cells including myofibroblasts and their progenitors were sorted by FACS from P8-9 lungs of control and Rap1iECKO mice, and subjected to collagen gel contraction assay. The contractile ability of PDGFRα(+) cells derived from Rap1iECKO mice was similar to that of control mouse-derived cells (Fig. 2k, l). Furthermore, PDGFRα(+) cells derived from Rap1iECKO mice and those from control mice exhibited a similar degree of nuclear YAP localization when plated on a glass-base dish (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e), indicating the mechanotransduction machinery to be preserved even in the Rap1iECKO mouse-derived cells. These results suggest that mechanical signaling in myofibroblasts is non-cell-autonomously impaired in Rap1iECKO mice.

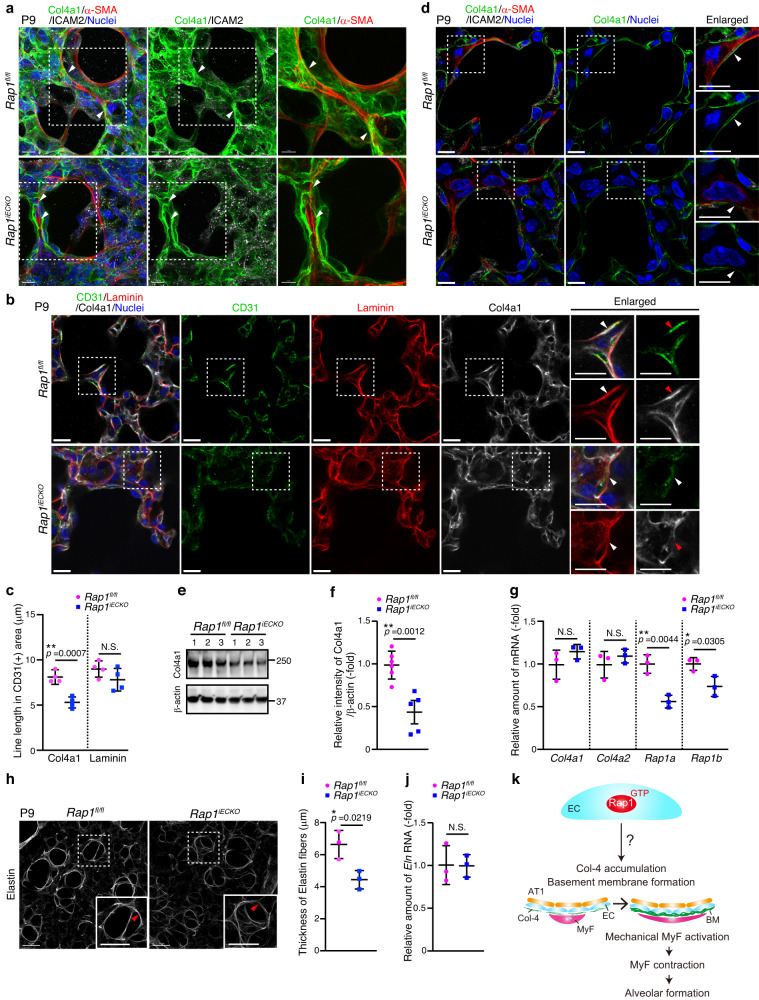

ECs induce Col-4 accumulation to generate BMs acting as a scaffold for myofibroblasts in a Rap1-dependent manner

The next question to address was how ECs regulate mechanical signaling in alveolar myofibroblasts in a Rap1-dependent manner. To tackle this issue, we first analyzed spatial localizations of ECs and myofibroblasts in alveoli (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Capillary ECs surrounded and created intimate contacts with AT1 cells to form alveoli in P9 lungs. Furthermore, myofibroblasts covered the outside of the alveolar space by making tight contacts with ECs. It can reasonably be assumed that BMs mediate an indirect contact between ECs and myofibroblasts. In addition, BMs are known to act as scaffolds for cells to regulate development and tissue morphogenesis32–34. Importantly, the stiffness of the extracellular matrix forming BMs has also been shown to stimulate mechanical signaling involved in various cellular functions35,36. Therefore, we hypothesized that ECs might regulate alveologenesis by constructing BMs acting as a scaffold for myofibroblasts. To address this hypothesis, we analyzed BMs during alveologenesis by visualizing Collagen Type IV Alpha 1 (Col4a1), a major BM component. Col4a1 was distributed throughout the alveoli in both control and Rap1iECKO mice (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3b). In controls, Col4a1 was well assembled and formed sheet-like BMs, which closely surrounded the alveolar myofibroblasts (Fig. 3a). In clear contrast, Col4a1 resulted in the construction of disorganized BMs that were loosely attached to the alveolar myofibroblasts in Rap1iECKO mice (Fig. 3a). Consistently, the single slice images revealed that control mice showed continuous BMs tightly attached to the alveolar myofibroblasts, while Rap1iECKO mice exhibited a discontinuous appearance of BMs surrounding the myofibroblasts (Fig. 3b–d and Supplementary Fig. 3c). We further investigated whether alveolar ECs in Rap1iECKO mice fail to form continuous BMs by conducting mosaic gene deletion analysis. To achieve mosaic deletion of Rap1a/b in ECs, a low dose of tamoxifen was delivered from the lactating mother into Rap1afl/fl;Rap1bfl/fl;Cdh5-CreERT2 postnatal mice with the mTmG reporter background (Rap1iECKO;mTmG mice) at P1, enabling the identification of ECs lacking Rap1a/b with membrane GFP (mGFP) fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Rap1afl/+;Rap1bfl/+;Cdh5-CreERT2 or Rap1afl/fl;Rap1bfl/fl;Cdh5-CreERT2 mice with the mTmG reporter background (Rap1iECHet;mTmG mice) served as a control. Col4a1 located around mGFP-labeled Rap1a/b-deficient ECs showed less assembly, forming discontinuous BMs, whereas that around the mGFP-labeled control ECs constructed continuous BMs (Supplementary Fig. 3e, f). These results raise the possibility of defective assembly of Col4a1 into stable BMs in Rap1iECKO mice. Additionally, we observed lower Col4a1 protein levels in the lungs of Rap1iECKO mice than in control lungs, despite similar mRNA levels of Col4a1 and Col4a2 in these two groups (Fig. 3e–g). Given that matrix metalloproteinase-2, also known as 72 kDa type IV collagenase, is known to be active during alveologenesis37, it is reasonable to assume that Col4a1 in the alveoli of Rap1iECKO mice undergoes digestion by collagenolytic enzymes, possibly due to impaired Col4a1 assembly. We also analyzed laminin, another BM component, and found that its localization in BMs was relatively well preserved even in Rap1iECKO mice (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 3b, c), revealing that ECs recruit Col-4, but not laminin, into BMs in a Rap1-dependent manner.

kDa type IV collagenase, is known to be active during alveologenesis37, it is reasonable to assume that Col4a1 in the alveoli of Rap1iECKO mice undergoes digestion by collagenolytic enzymes, possibly due to impaired Col4a1 assembly. We also analyzed laminin, another BM component, and found that its localization in BMs was relatively well preserved even in Rap1iECKO mice (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 3b, c), revealing that ECs recruit Col-4, but not laminin, into BMs in a Rap1-dependent manner.

a Confocal z-projection images for Col4a1 (green), α-SMA (red), ICAM2 (white), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9. Arrowheads, Col4a1-based BMs surrounding myofibroblasts. b Single slice images for CD31 (green), Laminin (red), Col4a1 (white), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9. Arrowheads, Col4a1 and Laminin associated with ECs. c Line lengths of Col4a1 (left) and Laminin (right) in CD31(+) areas, as in (b) (n =

= 4 mice/each). d Single slice images for Col4a1 (green), α-SMA (red), ICAM2 (white), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9. Arrowheads, BMs localizing between ECs and myofibroblasts. e Western blot analysis of expressions of Col4a1 and β-actin in lungs of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9 (3 mice/each). f Expression levels of Col4a1 relative to those of β-actin, as in (e) (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n

4 mice/each). d Single slice images for Col4a1 (green), α-SMA (red), ICAM2 (white), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9. Arrowheads, BMs localizing between ECs and myofibroblasts. e Western blot analysis of expressions of Col4a1 and β-actin in lungs of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9 (3 mice/each). f Expression levels of Col4a1 relative to those of β-actin, as in (e) (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n =

= 6 and 5 mice). g Expression levels of Col4a1, Col4a2, Rap1a, and Rap1b mRNA relative to those of Actb in lungs of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9 (n

6 and 5 mice). g Expression levels of Col4a1, Col4a2, Rap1a, and Rap1b mRNA relative to those of Actb in lungs of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9 (n =

= 3 mice/each). h Confocal z-projection images for Elastin in alveoli from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9. i Thicknesses of Elastin fibers, as in (h) (n

3 mice/each). h Confocal z-projection images for Elastin in alveoli from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9. i Thicknesses of Elastin fibers, as in (h) (n =

= 3 mice/each). j Expression levels of Eln mRNA relative to those of Actb in lungs of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9 (n

3 mice/each). j Expression levels of Eln mRNA relative to those of Actb in lungs of Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9 (n =

= 3 mice/each). k Schematic diagram illustrating how ECs regulate the function of alveolar myofibroblasts. ECs induce BM formation by accumulating Col-4 in a Rap1-dependent manner. BMs constructed by ECs appear to serve as a scaffold for myofibroblasts to induce alveolar formation. Each dot represents an individual mouse, and data are presented as means

3 mice/each). k Schematic diagram illustrating how ECs regulate the function of alveolar myofibroblasts. ECs induce BM formation by accumulating Col-4 in a Rap1-dependent manner. BMs constructed by ECs appear to serve as a scaffold for myofibroblasts to induce alveolar formation. Each dot represents an individual mouse, and data are presented as means ±

± s.d. (c, f, g, i, j). N.S. no significance; **P

s.d. (c, f, g, i, j). N.S. no significance; **P <

< 0.01, *P

0.01, *P <

< 0.05, by two-tailed Student’s t-test (c, f, g, i, j). Boxed areas are enlarged on the right (a, d, b) and in the insets (h). Scale bars; 10

0.05, by two-tailed Student’s t-test (c, f, g, i, j). Boxed areas are enlarged on the right (a, d, b) and in the insets (h). Scale bars; 10 μm (a, d), 7

μm (a, d), 7 μm (enlarged in a), 15

μm (enlarged in a), 15 μm (b), 50

μm (b), 50 μm (h). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

μm (h). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Alveolar myofibroblasts secrete and assemble elastin into elastic fibers which are mechanically required for alveolar formation9. Thus, we next analyzed elastic fibers in alveoli and found that they localized around the alveolar entry ring in both control and Rap1iECKO mice (Fig. 3h). However, quantitative analysis revealed that the elastic fibers surrounding the alveolar entry ring were thinner in Rap1iECKO mice than in control mice, although expression of Elastin mRNA in the lungs differed minimally between these two groups (Fig. 3i, j and Supplementary Movie 3, 4), supporting the hypothesis that functions of alveolar myofibroblasts are impaired in Rap1iECKO mice. Collectively, these findings suggest that ECs Rap1-dependently generate BMs required for myofibroblasts to induce mechanical signal-mediated alveologenesis (Fig. 3k).

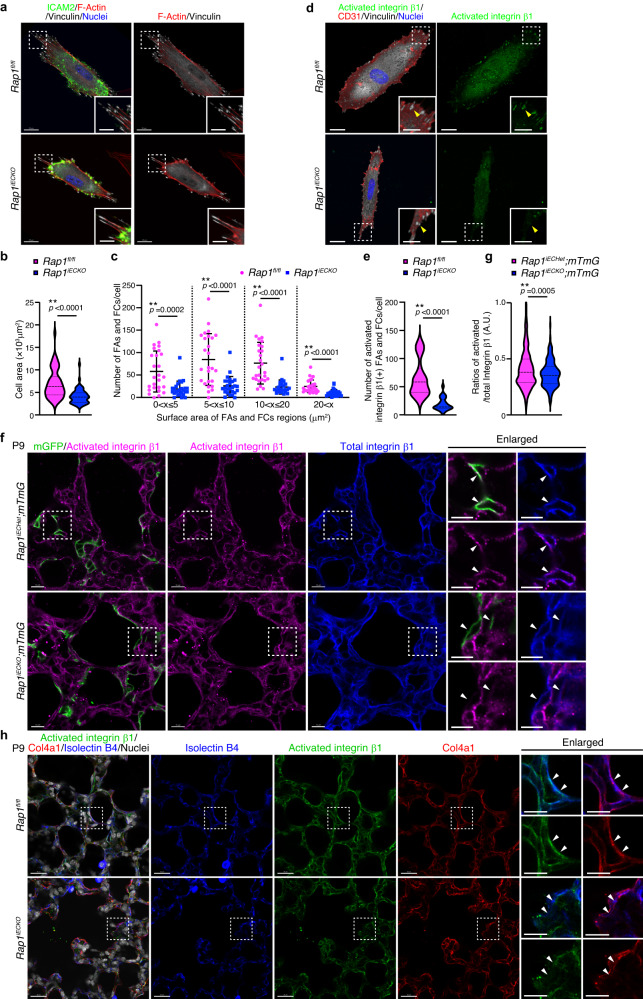

Rap1 stimulates adhesive activity of integrin β1 in alveolar ECs

We next investigated the molecular mechanism by which endothelial Rap1 induces BM formation. Rap1 stimulates the adhesive activity of integrins to promote cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix38,39. Importantly, a previous report showed that RAP-3, a C. elegans orthologue of mammalian Rap1, activates PAT-2 (α-subunit)/PAT-3 (β-subunit) integrins, which in turn promote Col-4 recruitment into BMs in a laminin-independent manner40. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that endothelial Rap1 activates integrins to induce Col-4 recruitment to BMs. To test this hypothesis, we first evaluated the adhesive activity of integrins in ECs of control and Rap1iECKO mouse lungs. To this end, ECs were isolated from the lungs of control and Rap1iECKO mice, plated onto dishes coated with Collagen Type I (Col-1), and subjected to analysis of integrin-mediated cell adhesion. Rap1iECKO mouse-derived ECs exhibited a significantly smaller cell area than control ECs (Fig. 4a, b). In addition, the number and size of focal adhesions (FAs) and focal complexes (FCs) were reduced in the ECs derived from Rap1iECKO mice as compared to those of control ECs (Fig. 4a, c), suggesting decreased adhesive activity of integrins in Rap1-deficient lung ECs. Consistently, the number of activated integrin β1-positive FAs/FCs was significantly decreased in the lung ECs isolated from Rap1iECKO mice as compared to those from control mice (Fig. 4d, e). These findings suggest that Rap1 is required for activation of integrins in lung ECs.

a–c Formation of FAs and FCs in ECs isolated from the lungs of P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice and cultured on collagen-coated dishes for 72 h. a Confocal fluorescence images for ICAM2 (green), F-actin (red), vinculin (white), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue). b Violin plots of the average cell area (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n

h. a Confocal fluorescence images for ICAM2 (green), F-actin (red), vinculin (white), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue). b Violin plots of the average cell area (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n =

= 90 and 71 cells from 3 mice). c Number of FAs/FCs per cell, within the indicated size range at the bottom. The dots represent individual cells. Data are means

90 and 71 cells from 3 mice). c Number of FAs/FCs per cell, within the indicated size range at the bottom. The dots represent individual cells. Data are means ±

± s.d. (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n

s.d. (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n =

= 90 and 71 cells from 3 mice). d Confocal fluorescence images for activated integrin β1 (green), CD31 (red), vinculin (white), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in ECs isolated from the lungs of P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice and cultured for 72

90 and 71 cells from 3 mice). d Confocal fluorescence images for activated integrin β1 (green), CD31 (red), vinculin (white), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in ECs isolated from the lungs of P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice and cultured for 72 h. Arrowheads, the activated integrin β1-positive FAs/FCs. e Violin plots indicate the average number of activated integrin β1-positive FAs/FCs per cell, as in d (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n

h. Arrowheads, the activated integrin β1-positive FAs/FCs. e Violin plots indicate the average number of activated integrin β1-positive FAs/FCs per cell, as in d (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n =

= 23 and 24 cells from 3 mice). f Single slice images for mGFP (green), activated integrin β1 (magenta), and integrin β1 (blue) in alveoli from Rap1iECHet;mTmG and Rap1iECKO;mTmG mice at P9. Arrowheads, mGFP-labeled plasma membranes of ECs. g Violin plots showing the ratio of the number of activated integrin β1 to the total integrin β1 per cell (arbitrary units, A.U.), as in (f) (Rap1iECHet;mTmG and Rap1iECKO;mTmG, n

23 and 24 cells from 3 mice). f Single slice images for mGFP (green), activated integrin β1 (magenta), and integrin β1 (blue) in alveoli from Rap1iECHet;mTmG and Rap1iECKO;mTmG mice at P9. Arrowheads, mGFP-labeled plasma membranes of ECs. g Violin plots showing the ratio of the number of activated integrin β1 to the total integrin β1 per cell (arbitrary units, A.U.), as in (f) (Rap1iECHet;mTmG and Rap1iECKO;mTmG, n =

= 433 and 217 ROIs from 3 mice). h Single slice images for activated integrin β1 (green), Col4a1 (red), isolectin B4 (blue), and Nuclei (DAPI, white) in alveoli from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9. Arrowheads, isolectin B4(+) ECs. In violin plots (b, e, g) bold and thin dashed lines indicate the median and quartiles, respectively. **P

433 and 217 ROIs from 3 mice). h Single slice images for activated integrin β1 (green), Col4a1 (red), isolectin B4 (blue), and Nuclei (DAPI, white) in alveoli from Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice at P9. Arrowheads, isolectin B4(+) ECs. In violin plots (b, e, g) bold and thin dashed lines indicate the median and quartiles, respectively. **P <

< 0.01, by two-tailed Student’s t-test (b, c, e, g). Boxed areas are enlarged in the insets (a, d) and on the right (f, h). Scale bars; 20

0.01, by two-tailed Student’s t-test (b, c, e, g). Boxed areas are enlarged in the insets (a, d) and on the right (f, h). Scale bars; 20 μm (a, d, h), 10

μm (a, d, h), 10 μm (f and enlarged images in a, d, h) and 7

μm (f and enlarged images in a, d, h) and 7 μm (enlarged images in f). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

μm (enlarged images in f). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

To further confirm the Rap1-mediated activation of integrins in alveolar ECs, we performed 3D immunofluorescence analysis of the lungs of Rap1iECHet;mTmG and Rap1iECKO;mTmG mice with the antibodies against integrin β1and its activated form. In both groups, integrin β1 was localized at the mGFP-labeled plasma membrane of alveolar ECs (Fig. 4f). However, the plasma membrane localization of the activated form of integrin β1 was significantly diminished in alveolar ECs of Rap1iECKO;mTmG mice as compared to those of Rap1iECHet;mTmG mice (Fig. 4f, g), indicating that Rap1 is required for activation of integrins in alveolar ECs. Furthermore, we observed that Col4a1 was assembled near the plasma membrane-localized activated integrin β1 in alveolar ECs of control mice (Fig. 4h). In contrast, alveolar ECs of Rap1iECKO mice exhibited a reduced plasma membrane localization of activated integrin β1 and Col4a1 assembly was only slightly induced around these ECs (Fig. 4h). Considered collectively, our results suggest that Rap1 activates integrin β1 in alveolar ECs to induce BM formation.

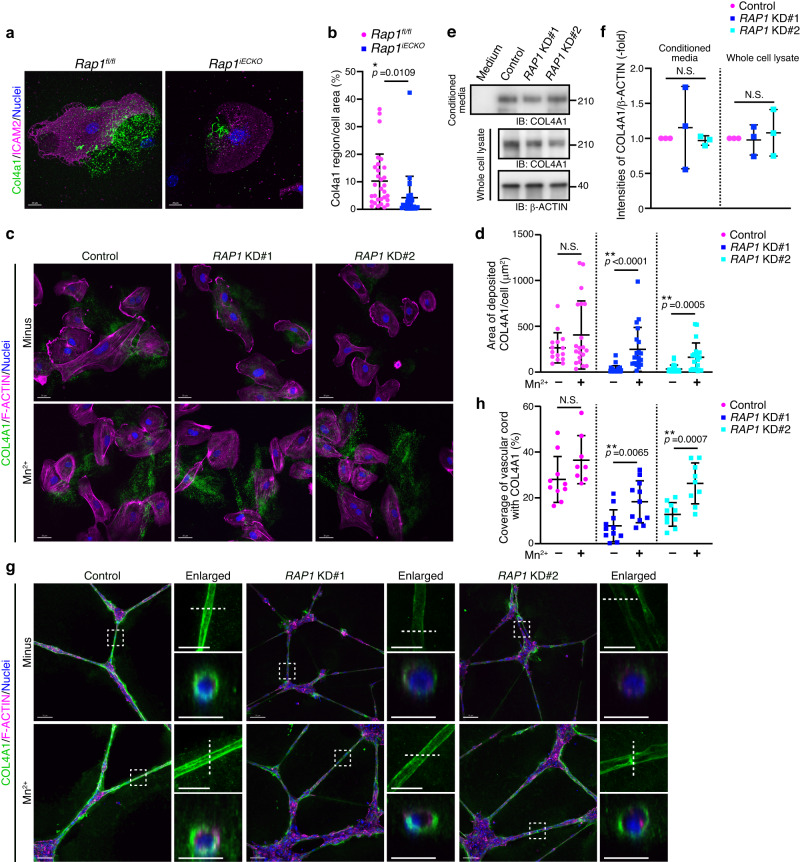

Rap1 generates BMs through integrin-mediated recruitment of Col-4

We next aimed to elucidate whether Rap1 induces Col-4 recruitment by activating integrin in ECs. For this purpose, lung ECs isolated from control and Rap1iECKO mice were cultured in Col-1-coated dishes for 72 h and then subjected to immunofluorescence staining with Col4a1 antibody. Col4a1 was deposited and assembled on the surface of the dish by control lung ECs (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). However, the amount of Col4a1 assembled on the dish was significantly decreased when lung ECs derived from Rap1iECKO mice were cultured (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). We also conducted the same experiments using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Control HUVECs deposited and assembled COL4A1 on the culture dish surface (Fig. 5c, d). However, depletion of both RAP1A and RAP1B led to a reduction of COL4A1 assembled on the dish without affecting the mRNA levels of COL4A1 and COL4A2 (Fig. 5c, d and Supplementary Fig. 4b–f). We also tested the possibility that the decreased amount of Col-4 assembled on the dish cultured with Rap1-depleted ECs is due to its degradation by performing Western blot analysis and found that the cellular protein levels of COL4A1 differed minimally between control and RAP1A/RAP1B-depleted HUVECs (Fig. 5e, f). In addition, similar amounts of COL4A1 protein were present in the conditioned media cultured with control and RAP1A/RAP1B-depleted HUVECs (Fig. 5e, f). These findings indicate that the depletion of Rap1 does not affect either the degradation or the secretion of Col-4 and thereby suggest that endothelial Rap1 actively regulates the assembly of Col-4.

h and then subjected to immunofluorescence staining with Col4a1 antibody. Col4a1 was deposited and assembled on the surface of the dish by control lung ECs (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). However, the amount of Col4a1 assembled on the dish was significantly decreased when lung ECs derived from Rap1iECKO mice were cultured (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). We also conducted the same experiments using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Control HUVECs deposited and assembled COL4A1 on the culture dish surface (Fig. 5c, d). However, depletion of both RAP1A and RAP1B led to a reduction of COL4A1 assembled on the dish without affecting the mRNA levels of COL4A1 and COL4A2 (Fig. 5c, d and Supplementary Fig. 4b–f). We also tested the possibility that the decreased amount of Col-4 assembled on the dish cultured with Rap1-depleted ECs is due to its degradation by performing Western blot analysis and found that the cellular protein levels of COL4A1 differed minimally between control and RAP1A/RAP1B-depleted HUVECs (Fig. 5e, f). In addition, similar amounts of COL4A1 protein were present in the conditioned media cultured with control and RAP1A/RAP1B-depleted HUVECs (Fig. 5e, f). These findings indicate that the depletion of Rap1 does not affect either the degradation or the secretion of Col-4 and thereby suggest that endothelial Rap1 actively regulates the assembly of Col-4.

a Confocal fluorescence images for Col4a1 (green), ICAM2 (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in ECs from the lungs of P9 Rap1fl/fl and Rap1iECKO mice and cultured on collagen-coated dishes for 72 h. b The amounts of Col4a1 assembled on the dish, as in (a), are expressed as percentages of Col4a1-positive area relative to ICAM2-labeled total cellular area (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n

h. b The amounts of Col4a1 assembled on the dish, as in (a), are expressed as percentages of Col4a1-positive area relative to ICAM2-labeled total cellular area (Rap1f/f and Rap1iECKO, n =

= 39 and 44 cells from 3 mice). c Confocal fluorescence images for COL4A1 (green), F-Actin (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in HUVECs transfected with control siRNA or two siRNA mixtures targeting both RAP1A and RAP1B (RAP1 KD#1, RAP1 KD#2) and cultured without or with 0.5

39 and 44 cells from 3 mice). c Confocal fluorescence images for COL4A1 (green), F-Actin (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in HUVECs transfected with control siRNA or two siRNA mixtures targeting both RAP1A and RAP1B (RAP1 KD#1, RAP1 KD#2) and cultured without or with 0.5 mM MnCl2 for 24

mM MnCl2 for 24 h. d The amounts of COL4A1 assembled on the dish, as in (c), are expressed as a COL4A1-positive area divided by the number of cells in each image (Numbers of analyzed cells are provided in Supplementary Table 3). e Western blot analysis of COL4A1 and β-actin. Upper, COL4A1 in the conditioned media cultured without (Medium) or with HUVECs transfected with the indicated siRNAs; lower, COL4A1 and β-actin in the corresponding whole cell lysates. f The amounts of COL4A1 in the conditioned media and whole cell lysates normalized by those of β-actin, as in (e), are expressed relative to the levels observed in the control groups (n

h. d The amounts of COL4A1 assembled on the dish, as in (c), are expressed as a COL4A1-positive area divided by the number of cells in each image (Numbers of analyzed cells are provided in Supplementary Table 3). e Western blot analysis of COL4A1 and β-actin. Upper, COL4A1 in the conditioned media cultured without (Medium) or with HUVECs transfected with the indicated siRNAs; lower, COL4A1 and β-actin in the corresponding whole cell lysates. f The amounts of COL4A1 in the conditioned media and whole cell lysates normalized by those of β-actin, as in (e), are expressed relative to the levels observed in the control groups (n =

= 3 independent experiments). g Confocal z-projection images for COL4A1 (green), F-Actin (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in vascular cord structures constructed by HUVECs transfected with the indicated siRNAs and cultured on Matrigel without or with 0.5

3 independent experiments). g Confocal z-projection images for COL4A1 (green), F-Actin (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in vascular cord structures constructed by HUVECs transfected with the indicated siRNAs and cultured on Matrigel without or with 0.5 mM MnCl2 for 24

mM MnCl2 for 24 h. Boxed areas are enlarged on the upper right. The cross-sectional images of the areas indicated by dotted lines are shown at the bottom. h Coverage of vascular cord structures with COL4A1, as in (g), are expressed as percentages relative to total vascular cord areas (Numbers of experiments are provided in Supplementary Table 3). Each dot represents an individual cell (b), image (d, h), and experiment (f). Data are presented as means

h. Boxed areas are enlarged on the upper right. The cross-sectional images of the areas indicated by dotted lines are shown at the bottom. h Coverage of vascular cord structures with COL4A1, as in (g), are expressed as percentages relative to total vascular cord areas (Numbers of experiments are provided in Supplementary Table 3). Each dot represents an individual cell (b), image (d, h), and experiment (f). Data are presented as means ±

± s.d. (b, d, f, h). N.S. no significance; **P

s.d. (b, d, f, h). N.S. no significance; **P <

< 0.01, *P

0.01, *P <

< 0.05, by two-tailed Student’s t-test (b, d, h) and by one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s post-hoc test (f). Scale bars; 20

0.05, by two-tailed Student’s t-test (b, d, h) and by one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s post-hoc test (f). Scale bars; 20 μm (a), 30

μm (a), 30 μm (c and upper enlarged images in g), 70

μm (c and upper enlarged images in g), 70 μm (g), 15

μm (g), 15 μm (lower enlarged images in g). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

μm (lower enlarged images in g). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Next, we investigated whether Rap1 induces Col-4 assembly through the activation of integrins. Manganese ions (Mn2+) reportedly increase the ligand-binding affinity of integrins41. Indeed, the treatment of HUVECs with Mn2+ increased the active form of integrin β1 localized at FAs (Supplementary Fig. 4g). Thus, we examined the effect of Mn2+ treatment on COL-4 assembly and showed that it partially rescued the assembly of COL4A1 by RAP1A/RAP1B-depleted HUVECs (Fig. 5c, d). These results suggest that ECs deposit and assemble Col-4 through Rap1-mediated activation of integrins.

To further confirm this notion, we performed a Matrigel-based in vitro cord formation assay using HUVECs. HUVECs were plated on Matrigel, allowed to form capillary-like network structures for 36 h, and then stained with anti-COL4A1 antibody to analyze BM formation. COL4A1 was accumulated around HUVEC-constructed cord-like structures to form BMs (Fig. 5g, h), a process completely inhibited by knockdown of COL4A1, indicating that COL4A1 assembled on the vessel wall had been deposited by HUVECs (Supplementary Fig. 4h–j). Depletion of both RAP1A and RAP1B severely inhibited accumulation of COL4A1 around the cord-like structures, while not impacting the expression levels of COL4A1 and COL4A2 mRNAs in HUVECs (Fig. 5g, h, Supplementary Fig. 4d). Furthermore, the Mn2+ treatment partially, yet significantly, rescued the diminished accumulation of COL4A1 around the cord-like structures in HUVECs depleted of both RAP1A and RAP1B (Fig. 5g, h). To further confirm the role of integrin β1 in BM formation, we treated HUVECs with blocking antibody against integrin β1 (mAb13)42, and found that COL4A1 accumulation around the cord-like structures was decreased by integrin β1 blocking antibody (Supplementary Fig. 4k, l). Taken together, these findings indicate that Rap1 induces Col-4 accumulation around vessel walls to form BM by stimulating the adhesive activity of integrins.

h, and then stained with anti-COL4A1 antibody to analyze BM formation. COL4A1 was accumulated around HUVEC-constructed cord-like structures to form BMs (Fig. 5g, h), a process completely inhibited by knockdown of COL4A1, indicating that COL4A1 assembled on the vessel wall had been deposited by HUVECs (Supplementary Fig. 4h–j). Depletion of both RAP1A and RAP1B severely inhibited accumulation of COL4A1 around the cord-like structures, while not impacting the expression levels of COL4A1 and COL4A2 mRNAs in HUVECs (Fig. 5g, h, Supplementary Fig. 4d). Furthermore, the Mn2+ treatment partially, yet significantly, rescued the diminished accumulation of COL4A1 around the cord-like structures in HUVECs depleted of both RAP1A and RAP1B (Fig. 5g, h). To further confirm the role of integrin β1 in BM formation, we treated HUVECs with blocking antibody against integrin β1 (mAb13)42, and found that COL4A1 accumulation around the cord-like structures was decreased by integrin β1 blocking antibody (Supplementary Fig. 4k, l). Taken together, these findings indicate that Rap1 induces Col-4 accumulation around vessel walls to form BM by stimulating the adhesive activity of integrins.

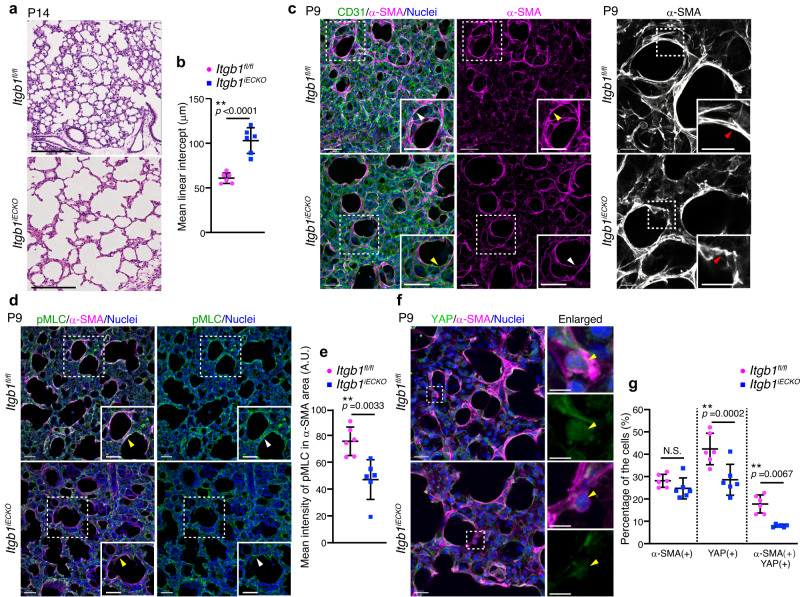

Integrin β1 generates BMs required for myofibroblast-mediated alveologenesis

Based on the above findings, we tested whether integrin β1 acts downstream from Rap1 to form the BMs required for mechanical signaling in myofibroblasts. To this end, we generated EC-specific Itgb1 deficient (Itgb1iECKO) mice by crossing floxed Itgb1 mice with Cdh5-CreERT2 transgenic mice. Endothelial Itgb1 was deleted after birth by delivering tamoxifen via the lactating mother for three consecutive days from P0. Expression of Itgb1 mRNA was partially, but significantly, decreased in CD31(+) ECs isolated from P9 lungs of Itgb1iECKO mice as compared to those from control mice, while its expressions in PDGFRα(+) cells containing myofibroblasts were similar in control and Itgb1iECKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b).

Therefore, we investigated the requirement of endothelial integrin β1 for alveolar morphogenesis. As observed in Rap1iECKO mice (Fig. 1d, e), Itgb1iECKO mice showed an increased MLI compared to control mice, indicating compromised alveologenesis in the Itgb1iECKO mice (Fig. 6a, b). Thus, we next tested whether the mechanical signaling required for alveologenesis is impaired in myofibroblasts of Itgb1iECKO mice. Although myofibroblasts localizing to the alveolar entry ring were present in Itgb1iECKO mice, their α-SMA filaments were thinner than those of control mice, as observed in Rap1iECKO mice (Figs. 2c, d, and and6c).6c). Consistently, the pMLC signal in alveolar myofibroblasts of Itgb1iECKO mice was dramatically attenuated compared to that in control siblings (Fig. 6d, e). Furthermore, fewer alveolar myofibroblasts exhibited the nuclear YAP signal in Itgb1iECKO mice than in control mice (Fig. 6f, g). These results show that mechanical signaling in alveolar myofibroblasts was compromised not only in Rap1iECKO mice but also in Itgb1iECKO mice.

a Images of HE-stained lung tissues from Itgb1fl/fl and Itgb1iECKO mice at P14. b Mean linear intercepts (MLI) in the lungs of Itgb1fl/fl and Itgb1iECKO mice at P14, as in (a) (n =

= 6 mice/each). c Confocal z-projection images for CD31 (green), α-SMA (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) (left two columns) and for α-SMA (white) (right column) in alveoli from Itgb1fl/fl and Itgb1iECKO mice at P9. Boxed areas are enlarged in the insets. Arrowheads, α-SMA filaments surrounding the alveolar entry ring. d Confocal z-projection images for pMLC (green), α-SMA (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from Itgb1fl/fl and Itgb1iECKO mice at P9. Boxed areas are enlarged in the insets. Arrowheads, the pMLC signal in myofibroblasts. e Fluorescence intensity of pMLC in α-SMA(+) areas (arbitrary units, A.U.), as in (d) (n

6 mice/each). c Confocal z-projection images for CD31 (green), α-SMA (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) (left two columns) and for α-SMA (white) (right column) in alveoli from Itgb1fl/fl and Itgb1iECKO mice at P9. Boxed areas are enlarged in the insets. Arrowheads, α-SMA filaments surrounding the alveolar entry ring. d Confocal z-projection images for pMLC (green), α-SMA (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from Itgb1fl/fl and Itgb1iECKO mice at P9. Boxed areas are enlarged in the insets. Arrowheads, the pMLC signal in myofibroblasts. e Fluorescence intensity of pMLC in α-SMA(+) areas (arbitrary units, A.U.), as in (d) (n =

= 6 mice/each). f Confocal z-projection images for YAP (green), α-SMA (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from Itgb1fl/fl and Itgb1iECKO mice at P9. Boxed areas are enlarged on the upper right. Enlarged YAP images are shown at the bottom. Arrowheads, the nuclei of α-SMA(+) myofibroblasts. g Percentages of α-SMA(+), nuclear YAP(+), and α-SMA(+)/nuclear YAP(+) cell populations, as in (f) (n

6 mice/each). f Confocal z-projection images for YAP (green), α-SMA (magenta), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from Itgb1fl/fl and Itgb1iECKO mice at P9. Boxed areas are enlarged on the upper right. Enlarged YAP images are shown at the bottom. Arrowheads, the nuclei of α-SMA(+) myofibroblasts. g Percentages of α-SMA(+), nuclear YAP(+), and α-SMA(+)/nuclear YAP(+) cell populations, as in (f) (n =

= 6 mice/each). Each dot represents an individual mouse, and data are presented as means

6 mice/each). Each dot represents an individual mouse, and data are presented as means ±

± s.d. (b, e, g). N.S. no significance; **P

s.d. (b, e, g). N.S. no significance; **P <

< 0.01, by two-tailed Student’s t-test (b, e, g). Scale bars; 50

0.01, by two-tailed Student’s t-test (b, e, g). Scale bars; 50 μm (a, d, and left images in c), 20

μm (a, d, and left images in c), 20 μm (f), 15

μm (f), 15 μm (right images in c), and 10

μm (right images in c), and 10 μm (enlarged images in f). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

μm (enlarged images in f). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

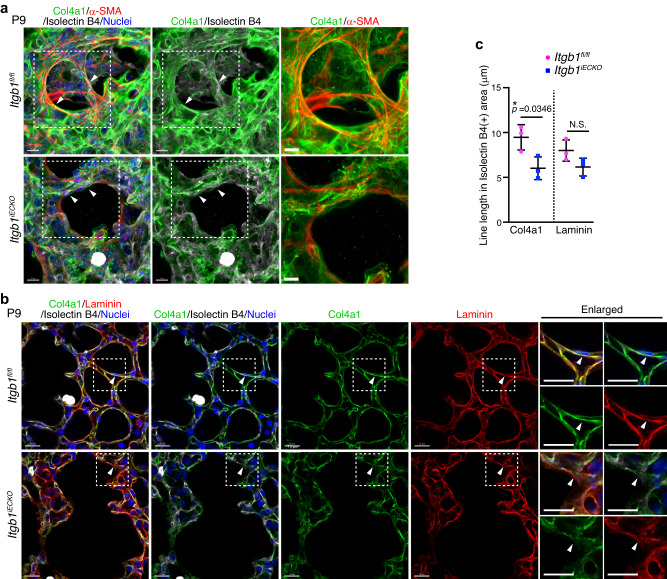

Finally, we investigated whether the BM formation required for mechanical signaling in myofibroblasts was inhibited in Itgb1iECKO mice. In control mice, BMs constructed by well-assembled Col4a1 tightly surrounded myofibroblasts localizing to the alveolar entry ring (Fig. 7a). In contrast, BMs consisting of Col4a1 showed disorganized morphology and were loosely attached to the alveolar myofibroblasts in Itgb1iECKO mice (Fig. 7a). Single slice images of alveoli also revealed that linear and continuous BMs constructed by Col4a1 and laminin were established along the ECs in control mice, whereas both Col4a1 and laminin were diffusely and discontinuously localized around the ECs in the alveoli of Itgb1iECKO mice (Fig. 7b, c and Supplementary Fig. 6). Altogether, these results indicate that endothelial Rap1 stimulates integrin β1 to induce the formation of BMs, which act as a scaffold for myofibroblasts and thereby induce mechanical signal-mediated alveologenesis (Fig. 8).

a Confocal z-projection images for Col4a1 (green), α-SMA (red), isolectin B4 (white), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from Itgb1fl/fl and Itgb1iECKO mice at P9. Boxed areas are enlarged on the right. Arrowheads, Col4a1-formed BMs surrounding the alveolar myofibroblasts. b Single slice fluorescence images for Col4a1 (green), Laminin (red), isolectin B4 (white), and Nuclei (DAPI, blue) in alveoli from Itgb1fl/fl and Itgb1iECKO mice at P9. Boxed areas are enlarged on the right. Arrowheads, the isolectin B4-labeled ECs. c Line lengths of Col4a1 (left) and Laminin (right) in isolectin B4(+) areas, as in (b). Each dot represents an individual mouse. Data are means ±

± s.d. (n

s.d. (n =

= 3 mice/each). N.S. no significance; *P

3 mice/each). N.S. no significance; *P <

< 0.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test (c). Scale bars; 10

0.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test (c). Scale bars; 10 μm (a), 7

μm (a), 7 μm (enlarged images in a), 15

μm (enlarged images in a), 15 μm (b). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

μm (b). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

During alveologenesis, alveolar ECs generate BMs by stimulating integrin β1-mediated recruitment of Col-4 in a Rap1-dependent manner. BMs formed by ECs act as a scaffold for alveolar myofibroblasts (MyF) to induce mechanical signal-mediated secondary septa formation, ultimately giving rise to alveoli.

Discussion

In this study, we uncovered a molecular mechanism underlying EC-mediated alveolar morphogenesis by analyzing EC-specific Rap1-deficient mice (Fig. 8). We demonstrated that Rap1iECKO mice exhibit hypo-alveolarization due to defective mechanical signaling in alveolar myofibroblasts, which is essential for the formation of secondary septa. As to the underlying mechanism, we discovered that alveolar ECs accomplish integrin β1-mediated recruitment of Col-4 and BM assembly in a Rap1-dependent manner, thereby acting as a scaffold for myofibroblasts allowing mechanical signal-induced secondary septa formation during alveologenesis.

Hypo-alveolarization in the lungs of Rap1iECKO mice is not secondary to growth retardation and/or defects in the development of other organs. It has been suggested that growth retardation and calorie restriction disrupt proper alveologenesis in postnatal and adult mice43,44. These findings raise the possibility that impaired formation of organs other than the lungs and subsequent growth retardation may cause hypo-alveolarization in Rap1iECKO mice, since Rap1 was deleted in all ECs throughout the body. However, this is not the case, since Rap1iECKO postnatal mice did not exhibit growth retardation, at least until P14, and the liver, stomach, and intestine developed normally. Consistent with these observations, mosaic gene deletion analysis of Rap1 in ECs further confirmed the requirement of Rap1 in alveolar ECs for proper alveologenesis. Thus, the growth retardation and defective formation of organs other than the lungs do not cause hypo-alveolarization in Rap1iECKO postnatal mice.

ECs contribute to organ morphogenesis not only by producing angiocrine factors but also via their cellular functions. It is now widely accepted that ECs produce angiocrine factors that actively regulate the development of various organs such as the lungs15, heart45, kidneys46, liver47, pancreas48, and bone49. Our present study revealed a mode of EC-mediated organ development in which ECs regulate alveolar morphogenesis via the formation of BMs. Similarly, we recently reported that ECs promote glomerular morphogenesis possibly by inducing blood filtration during pronephros formation in zebrafish embryos50. Hence, cellular functions mediated by ECs might play a crucial role in various types of organ morphogenesis. In addition, such intrinsic EC functions might also regulate organ regeneration and the pathogenesis of various diseases, as do EC-derived angiocrine factors. Thus, future studies are anticipated to clarify further unexpected roles of EC functions, deepening our understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of organ formation, maintenance, regeneration and dysfunction.

How do ECs induce Col-4 assembly to form BMs through Rap1-mediated activation of integrin β1? BMs are composed of laminin, Col-4, nidogen, and perlecan, among which laminin and Col-4 self-assemble into two independent supramolecular networks51,52. BM formation reportedly begins through laminin binding to cell surface receptors such as integrins and dystroglycan52. Laminin scaffolds on the cell surface subsequently recruit Col-4 networks via nidogens. Thus, Col-4 incorporation into BMs is thought to require laminin scaffolds on cell surfaces. However, in Rap1iECKO mice, Col-4 localization in BMs around alveolar myofibroblasts was disorganized, despite laminin localization being relatively well preserved, indicating that laminin scaffolds are not sufficient to correctly accumulate Col-4 at BMs. In this regard, laminin-independent mechanisms for recruiting Col-4 into BMs have been reported40,53. Jayadev et al. showed that Col-4 is incorporated into the gonadal and pharyngeal BMs in C. elegans at a postembryonic stage in laminin-dependent and laminin-independent manners, respectively. They showed that INA-1/PAT-3 integrin was selectively activated to recruit laminin at the gonad, thereby directing Col-4 incorporation into BMs, whereas PAT-2/PAT-3 integrin promoted Col-4 recruitment into the pharyngeal BMs in a laminin-independent manner. Importantly, they also found that Rap1 activates the PAT-2/PAT-3 integrins to recruit Col-4. Therefore, ECs might stimulate Rap1 to activate collagen-binding integrins, which would in turn recruit Col-4 into BMs required for myofibroblast function. Among the collagen-binding integrins, α1β1 and α2β1 integrins are known to be major receptors for Col-4 and to regulate diverse biological functions such as cell adhesion, cell migration, insulin secretion, and inflammation by binding to Col-454,55. Indeed, publicly available scRNA-seq data of the lungs showed that ECs in lungs of postnatal mice express Itga1 and Itga2 as well as Itgb156. Thus, α1β1 and α2β1 integrins might be activated by Rap1 in ECs, thereby binding and accumulating Col-4 to generate BMs. On the other hand, Itgb1iECKO mice exhibited impaired accumulation of both Col-4 and laminin at BMs. Hence, ECs might also promote laminin incorporation into BMs by stimulating laminin-binding integrins such as α6β1 integrins independently of Rap1.

EC-generated BMs act as a stiff scaffold for alveolar myofibroblasts, leading to the induction of alveologenesis through activation of mechanical signaling. Substrate stiffness influences a wide range of cellular responses such as cell adhesion, migration, survival, proliferation, and differentiation36,57. Indeed, differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and their cellular functions are known to be markedly affected by matrix stiffness58. During alveologenesis, myofibroblasts contract to form secondary septa by activating mechanical signaling involving myosin activation and nuclear YAP localization. Activation of such mechanical signaling is thought to depend on substrate stiffness59. Therefore, it is assumed that alveolar myofibroblasts induce activation of mechanical signaling by sensing the stiffness of EC-generated BMs. Indeed, BM mechanics have been widely suggested to regulate development, homeostasis, and various disease processes33,60. If this is the case, how do myofibroblasts sense the stiffness of EC-generated BMs? Cells sense substrate stiffness via integrin-mediated cell adhesion complexes, which link the extracellular matrix to the actin cytoskeleton61. Therefore, myofibroblasts might sense BM stiffness by adhering to BM components such as Col-4 via integrins. In addition, a prior study showed that BMs promote rapid and robust fibronectin assembly using sliding FAs driven by a contractile winch, thereby leading to accumulation of fibronectin at BMs62. It has also been reported that alveolar myofibroblasts adhere to fibronectin via α5β1 integrins, which is a requirement for alveologenesis63. Thus, myofibroblasts might sense the stiffness of BMs through integrin-mediated adhesion to fibronectin assembled on the EC-generated BMs. These hypotheses merit detailed examination in future studies.

This study has limitations, one of which is that the cause of lethality in Rap1iECKO mice was not identified. The hypo-alveolarization exhibited by Rap1iECKO mice might not be the cause of postnatal death, since suppression of alveolar septation reportedly does not lead to postnatal death64. Hence, further investigation is required to identify the cause of death in Rap1iECKO mice. Another limitation is that our results do not reveal the morphogenetic processes of alveolar formation. We analyzed alveologenesis by performing 3D immunofluorescence analysis of fixed lung tissues. However, analyzing 3D still images of alveoli is insufficient to illustrate morphogenetic processes of alveolar formation, which are highly complex and dynamic. Thus, live-imaging techniques, which are challenging to perform, are required to meaningfully elucidate the morphogenetic processes of alveolar formation.

In summary, our data demonstrate that ECs facilitate alveologenesis in postnatal lungs by constructing BMs through Rap1-mediated activation of integrin β1, which is required for activation of mechanical signaling in myofibroblasts. Our findings are not only important for understanding lung development but may also have implications relevant to lung disease. Surgical removal of lung lobes, i.e., pneumonectomy, induces compensatory growth of the remaining lobes not only through the growth of existing alveoli but also via the formation of new alveolar units by reactivated alveolar myofibroblasts65,66. Stimulating EC-mediated BM formation might be an effective therapeutic strategy to induce realveolarization, not only after pneumectomy, but also for lung diseases such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Methods

Mice

Animal experiments were approved by the animal committees of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, the Nippon Medical School, and Tokyo Medical and Dental University and performed by following the guidelines of the National Cerebral, Cardiovascular Center and the Nippon Medical School, and Tokyo Medical and Dental University.

Mice were housed in 12:12 light:dark light cycles at ambient temperature ranging between 20 °C and 23

°C and 23 °C and humidities between 30% and 70%. All mouse lines used in this study were in the C57BL/6

°C and humidities between 30% and 70%. All mouse lines used in this study were in the C57BL/6 J background. Rap1a and Rap1b double-floxed mice (B6;129S-Rap1atmMorz;Rap1btm1Morz/J) and Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo /J, a cell membrane-targeted, two-color fluorescent Cre-reporter line (ROSA-mTmG) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory67. Cdh5-CreERT2 mice expressing CreERT2 recombinase under the control of the Cdh5 promoter68 and Itgb1-floxed mice69 were previously described in detail. Rap1afl/fl;Rap1bfl/fl mice and Itgb1fl/fl mice were crossed with Cdh5-CreERT2 mice to specifically delete both Rap1a and Rap1b and Itgb1 in ECs upon tamoxifen treatment. Rap1afl/fl;Rap1bfl/fl mice and Itgb1fl/fl mice were used as littermate controls. To achieve tamoxifen-induced recombination in postnatal mice, 20

J background. Rap1a and Rap1b double-floxed mice (B6;129S-Rap1atmMorz;Rap1btm1Morz/J) and Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo /J, a cell membrane-targeted, two-color fluorescent Cre-reporter line (ROSA-mTmG) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory67. Cdh5-CreERT2 mice expressing CreERT2 recombinase under the control of the Cdh5 promoter68 and Itgb1-floxed mice69 were previously described in detail. Rap1afl/fl;Rap1bfl/fl mice and Itgb1fl/fl mice were crossed with Cdh5-CreERT2 mice to specifically delete both Rap1a and Rap1b and Itgb1 in ECs upon tamoxifen treatment. Rap1afl/fl;Rap1bfl/fl mice and Itgb1fl/fl mice were used as littermate controls. To achieve tamoxifen-induced recombination in postnatal mice, 20 mg/ml tamoxifen (T5648, Sigma–Aldrich) dissolved in corn oil was orally administered into the lactating dams for three consecutive days from P0 (75

mg/ml tamoxifen (T5648, Sigma–Aldrich) dissolved in corn oil was orally administered into the lactating dams for three consecutive days from P0 (75 μg/g/day). Littermate control postnatal mice also received tamoxifen from the lactating dams. A 20

μg/g/day). Littermate control postnatal mice also received tamoxifen from the lactating dams. A 20 mg dose of tamoxifen was dissolved with 1

mg dose of tamoxifen was dissolved with 1 ml of corn oil by sonication followed by vigorous shaking at 65

ml of corn oil by sonication followed by vigorous shaking at 65 °C under dark conditions, and then stored at −20

°C under dark conditions, and then stored at −20 °C for up to 1 week in the dark.

°C for up to 1 week in the dark.

The mosaic depletion of Rap1a and Rap1b was carried out as describe in the Supplementary Fig. 3d. The Rap1afl/fl;Rap1bfl/fl;Cdh5-CreERT2 mice were crossed with the Rap1afl/+;Rap1bfl/+;ROSA-mTmG mice. Then, the mother was orally gavaged with amoxifen (7.5 μg/g/day) only at P1, administering a low dose of tamoxifen to the Rap1afl/fl;Rap1bfl/fl;Cdh5-CreERT2;ROSA-mTmG (Rap1iECKO;mTmG) pups through the mother’s milk. The alveolar ECs lacking the Rap1a and Rap1b were identified based on the fluorescence of mGFP. The Rap1afl/+;Rap1bfl/+;Cdh5-CreERT2;ROSA-mTmG mice or Rap1afl/fl;Rap1bfl/fl;Cdh5-CreERT2;ROSA-mTmG (Rap1iECHet;mTmG) mice served as a control.

μg/g/day) only at P1, administering a low dose of tamoxifen to the Rap1afl/fl;Rap1bfl/fl;Cdh5-CreERT2;ROSA-mTmG (Rap1iECKO;mTmG) pups through the mother’s milk. The alveolar ECs lacking the Rap1a and Rap1b were identified based on the fluorescence of mGFP. The Rap1afl/+;Rap1bfl/+;Cdh5-CreERT2;ROSA-mTmG mice or Rap1afl/fl;Rap1bfl/fl;Cdh5-CreERT2;ROSA-mTmG (Rap1iECHet;mTmG) mice served as a control.

HE staining

Lungs, liver, stomach, and small intestine were perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) through the right ventricle of the heart, then inflated by injecting 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS containing NaN3 (PBS/NaN3) through the trachea, and fixed for 15 min. Then, the whole organs were harvested and kept overnight in 4% PFA/PBS/NaN3 at 4

min. Then, the whole organs were harvested and kept overnight in 4% PFA/PBS/NaN3 at 4 °C. After fixation, they were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin wax. The paraffin-embedded blocks of the organs were cut into 4

°C. After fixation, they were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin wax. The paraffin-embedded blocks of the organs were cut into 4 μm tissue sections and stained with a standard HE staining procedure using 1% Eosin Y Solution (Wako) and Mayer’s Hematoxylin Solution (Wako) according to a previously described method37. Then, the specimens were mounted in Canada Balsam (KANTO CHEMICAL CO., INC.) and imaged employing fluorescence microscopy (KEYENCE, BZ-X710).

μm tissue sections and stained with a standard HE staining procedure using 1% Eosin Y Solution (Wako) and Mayer’s Hematoxylin Solution (Wako) according to a previously described method37. Then, the specimens were mounted in Canada Balsam (KANTO CHEMICAL CO., INC.) and imaged employing fluorescence microscopy (KEYENCE, BZ-X710).

Cell isolation from lungs

Cell isolation using flow cytometry was performed in accordance with a method described previously70. Briefly, the lungs were perfused with ice-cold PBS via the right ventricle of the heart and inflated by injecting 1 ml of 25

ml of 25 U/ml Dispase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) dissolved in PBS through the trachea. The lungs were then excised, followed by removal of bronchi and other tissues. All lobes were transferred into a 6-well plate filled with 5

U/ml Dispase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) dissolved in PBS through the trachea. The lungs were then excised, followed by removal of bronchi and other tissues. All lobes were transferred into a 6-well plate filled with 5 ml of digestion buffer containing 100

ml of digestion buffer containing 100 μg/ml LiberaseTM (Roche), 0.1

μg/ml LiberaseTM (Roche), 0.1 mg/ml DNaseI (Sigma–Aldrich), and 25

mg/ml DNaseI (Sigma–Aldrich), and 25 mM HEPES, and then extensively minced with scissors. Subsequently, the minced lungs were mixed by pipetting several times using a P1000 pipet equipped with a truncated blue tip, transferred into 50

mM HEPES, and then extensively minced with scissors. Subsequently, the minced lungs were mixed by pipetting several times using a P1000 pipet equipped with a truncated blue tip, transferred into 50 ml conical tubes, and incubated in a 37

ml conical tubes, and incubated in a 37 °C water bath for 30

°C water bath for 30 min, during which the lungs were extensively pipetted, every 5

min, during which the lungs were extensively pipetted, every 5 min, using a P1000 pipet tip. After the incubation, 5

min, using a P1000 pipet tip. After the incubation, 5 ml of FACS buffer (PBS containing 2% fetal calf serum) were added to stop the digestion reaction. Then, the suspended cells were passed through a 100

ml of FACS buffer (PBS containing 2% fetal calf serum) were added to stop the digestion reaction. Then, the suspended cells were passed through a 100 μm mesh cell strainer and collected by centrifugation at 330

μm mesh cell strainer and collected by centrifugation at 330 ×

× g for 5

g for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended with 5

min. The cell pellet was resuspended with 5 ml of red blood cell lysing buffer (Funakoshi) and incubated for 4

ml of red blood cell lysing buffer (Funakoshi) and incubated for 4 min at room temperature (RT). After the incubation, the lysing reaction was stopped by adding 5

min at room temperature (RT). After the incubation, the lysing reaction was stopped by adding 5 ml of FACS buffer. The suspended cells were passed through a 40

ml of FACS buffer. The suspended cells were passed through a 40 μm mesh cell strainer, collected by centrifugation at 330

μm mesh cell strainer, collected by centrifugation at 330 ×

× g for 5

g for 5 min, and resuspended in 800

min, and resuspended in 800 μl of FACS buffer.

μl of FACS buffer.

To achieve sorting of CD31(+) cells and PDGFRα(+) cells, PE-conjugated anti-CD31(BioLegend, 1/200) and APC-conjugated anti-PDGFRα (eBioscience, 1/200) antibodies were used for positive selection, while FITC-conjugated anti-CD45 (BioLegend, 1/200), FITC-conjugated anti-TER119 (BioLegend, 1/200), and FITC-conjugated anti-CD326/EpCAM (BioLegend, 1/200) antibodies were used for negative selection (Supplementary Table 1). For immunostaining, the cells were incubated in FACS buffer containing the above-mentioned antibodies for 30 min on ice with intermittent mixing. After washing with a 10-fold volume of FACS buffer, the cells were resuspended in 1

min on ice with intermittent mixing. After washing with a 10-fold volume of FACS buffer, the cells were resuspended in 1 ml of FACS buffer containing SYTOX Blue (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1/500) to label the dead cells. Then, more than 5

ml of FACS buffer containing SYTOX Blue (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1/500) to label the dead cells. Then, more than 5 ×

× 106 cells showing FITC(−), APC (−), SYTOX Blue(−), and PE(+) and those showing FITC(−), PE(−), SYTOX Blue(−), and APC(+) were collected as CD31(+) and PDGFRα(+) cell populations, respectively, employing a cell sorter, BD FACSAriaTM Fusion (BD biosciences), using a 100

106 cells showing FITC(−), APC (−), SYTOX Blue(−), and PE(+) and those showing FITC(−), PE(−), SYTOX Blue(−), and APC(+) were collected as CD31(+) and PDGFRα(+) cell populations, respectively, employing a cell sorter, BD FACSAriaTM Fusion (BD biosciences), using a 100 μm nozzle and FACS Diva software. Then, the sorted cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 330

μm nozzle and FACS Diva software. Then, the sorted cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 330 ×

× g for 10

g for 10 min, and used for the experiments or stored at −80

min, and used for the experiments or stored at −80 °C for RNA purification.

°C for RNA purification.

RNA preparation

To extract total RNA from mouse lungs, the lobes excised from P9 mice were homogenized in TRIzol RNA Isolation Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a Physcotron homogenizer (MICROTEC CO., LTD.) for 30 s and subjected to RNA isolation steps according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted total RNA was further purified using the RNeasy Plus Kit (QIAGEN) and reverse-transcribed using SuperScriptTM III Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) together with 10

s and subjected to RNA isolation steps according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted total RNA was further purified using the RNeasy Plus Kit (QIAGEN) and reverse-transcribed using SuperScriptTM III Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) together with 10 mM dNTPs, RNase OUT ribonuclease inhibitor (TOYOBO), and random primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

mM dNTPs, RNase OUT ribonuclease inhibitor (TOYOBO), and random primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

To isolate total RNA from FACS-sorted cells, 0.5–1 ×

× 107 cells were lysed in 300

107 cells were lysed in 300 μl TRIzol RNA Isolation Reagents by employing extensive pipetting. Then, the cell lysates were mixed with the same volume of 100% EtOH, vortexed vigorously, and subjected to a further purification procedure using a Direct-zolTM RNA MicroPrep kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified RNA was reverse-transcribed using a SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

μl TRIzol RNA Isolation Reagents by employing extensive pipetting. Then, the cell lysates were mixed with the same volume of 100% EtOH, vortexed vigorously, and subjected to a further purification procedure using a Direct-zolTM RNA MicroPrep kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified RNA was reverse-transcribed using a SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

qPCR

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed employing a CFX96 Touch Deep Well real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) using KOD SYBR qPCR Mix (TOYOBO) or Thunderbird Next SYBR qPCR Mix (TOYOBO). The primers used for qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

3D immunofluorescence staining of alveoli

3D immunofluorescence staining of the lungs was conducted according to a previously described method70. Briefly, P9 mice were anesthetized with an anesthetic reagent containing 75 μg/ml medetomidine, 400

μg/ml medetomidine, 400 μg/ml midazolam, and 500

μg/ml midazolam, and 500 μg/ml butorphanol. After opening the chest cavity, the lungs were refluxed with PBS through the right ventricle to remove blood and subsequently perfused with 1

μg/ml butorphanol. After opening the chest cavity, the lungs were refluxed with PBS through the right ventricle to remove blood and subsequently perfused with 1 ml of pre-warmed 6% gelatin in PBS. Then, the lungs were inflated by injecting pre-warmed 1% low melting agarose (LMT) (Nacalai tesque, Inc.) in PBS through the trachea, allowing the filling of alveolar tissues with the gel. After this process, the lungs were immediately chilled with crushed ice for 5

ml of pre-warmed 6% gelatin in PBS. Then, the lungs were inflated by injecting pre-warmed 1% low melting agarose (LMT) (Nacalai tesque, Inc.) in PBS through the trachea, allowing the filling of alveolar tissues with the gel. After this process, the lungs were immediately chilled with crushed ice for 5 min to solidify the agarose, excised, and fixed in pre-cooled 2% PFA in PBS at 4

min to solidify the agarose, excised, and fixed in pre-cooled 2% PFA in PBS at 4 °C for 30

°C for 30 min. After confirming that the gel-filled lungs had solidified, the lobes were separated from each other and placed directly on a cutting stage with glue. Then, 250–300

min. After confirming that the gel-filled lungs had solidified, the lobes were separated from each other and placed directly on a cutting stage with glue. Then, 250–300 μm-thick sections were cut from the lobes with a VT1200S vibratome (Leica), fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 1

μm-thick sections were cut from the lobes with a VT1200S vibratome (Leica), fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 1 h at 4

h at 4 °C, and washed with PBS/NaN3. Subsequently, the tissue sections were warmed to 55

°C, and washed with PBS/NaN3. Subsequently, the tissue sections were warmed to 55 °C for 30

°C for 30 min in PBS/NaN3 to melt out the agarose gel. After repeating this step once, the specimens were blocked with blocking solution (5% normal goat serum and 0.25% TritonX-100 in PBS/NaN3) for 30

min in PBS/NaN3 to melt out the agarose gel. After repeating this step once, the specimens were blocked with blocking solution (5% normal goat serum and 0.25% TritonX-100 in PBS/NaN3) for 30 min at 4

min at 4 °C. Then, individual tissue sections were placed in each well of a 24-well plate and immunostained with primary antibodies in 250

°C. Then, individual tissue sections were placed in each well of a 24-well plate and immunostained with primary antibodies in 250 μl blocking solution at 4

μl blocking solution at 4 °C overnight. After washing with PBS/NaN3 at 4

°C overnight. After washing with PBS/NaN3 at 4 °C three times, 30

°C three times, 30 min each time, the tissue sections were further incubated with secondary antibodies in 250

min each time, the tissue sections were further incubated with secondary antibodies in 250 μl blocking solution at 4

μl blocking solution at 4 °C overnight and washed with 500

°C overnight and washed with 500 μl of PBS/NaN3 at 4

μl of PBS/NaN3 at 4 °C three times, 30

°C three times, 30 min each time. The primary and secondary antibodies used for 3D immunofluorescence staining of alveoli are listed in Supplementary Table 1. To mount the tissue sections on slides, mending tape with a square hollow for placing specimens was attached to the slides (Matsunami Glass). The tissue samples were placed in the hollows on the slides filled with handmade mounting media containing 2.5% DABCO, 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane, 50