Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia and results in a high risk of stroke. The number of immigrants is increasing globally, but little is known about potential differences in AF care across migrant populations.Aim

To investigate if initiation of oral anticoagulation therapy (OAC) differs for patients with incident AF in relation to country of origin.Methods

A nationwide register-based study covering 1999-2017. AF was defined as a first-time diagnosis of AF and a high risk of stroke. Stroke risk was defined according to guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Poisson regression adjusted for sex, age, socioeconomic position and comorbidity was made to compute incidence rate ratios (IRR) for initiation of OAC.Results

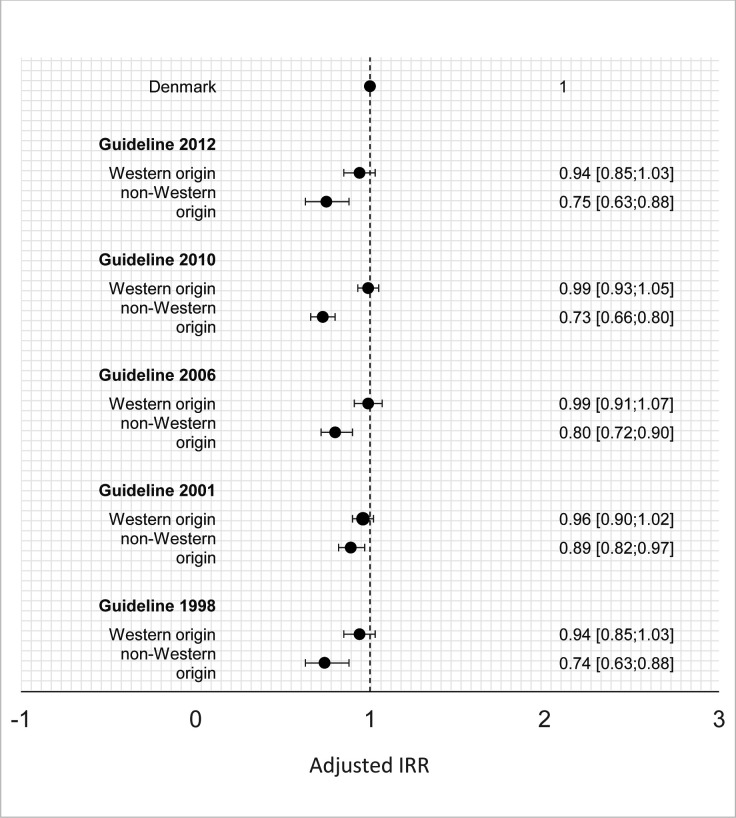

The AF population included 254 586 individuals of Danish origin, 6673 of Western origin and 3757 of non-Western origin. Overall, OAC was initiated within -30/+90 days relative to the AF diagnosis in 50.3% of individuals of Danish origin initiated OAC, 49.6% of Western origin and 44.5% of non-Western origin. Immigrants from non-Western countries had significantly lower adjusted IRR of initiating OAC according to all ESC guidelines compared with patients of Danish origin. The adjusted IRRs ranged from 0.73 (95% CI: 0.66 to 0.80) following the launch of the 2010 ESC guideline to 0.89 (95% CI: 0.82 to 0.97) following the launch of the 2001 ESC guideline.Conclusion

Patients with AF with a high risk of stroke of non-Western origin have persistently experienced a lower chance of initiating OAC compared with patients of Danish origin during the last decades.Free full text

Original research

Oral anticoagulation therapy initiation in patients with atrial fibrillation in relation to world region of origin: a register-based nationwide study

Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia and results in a high risk of stroke. The number of immigrants is increasing globally, but little is known about potential differences in AF care across migrant populations.

Aim

To investigate if initiation of oral anticoagulation therapy (OAC) differs for patients with incident AF in relation to country of origin.

Methods

A nationwide register-based study covering 1999–2017. AF was defined as a first-time diagnosis of AF and a high risk of stroke. Stroke risk was defined according to guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Poisson regression adjusted for sex, age, socioeconomic position and comorbidity was made to compute incidence rate ratios (IRR) for initiation of OAC.

Results

The AF population included 254 586 individuals of Danish origin, 6673 of Western origin and 3757 of non-Western origin. Overall, OAC was initiated within −30/+90 days relative to the AF diagnosis in 50.3% of individuals of Danish origin initiated OAC, 49.6% of Western origin and 44.5% of non-Western origin. Immigrants from non-Western countries had significantly lower adjusted IRR of initiating OAC according to all ESC guidelines compared with patients of Danish origin. The adjusted IRRs ranged from 0.73 (95% CI: 0.66 to 0.80) following the launch of the 2010 ESC guideline to 0.89 (95% CI: 0.82 to 0.97) following the launch of the 2001 ESC guideline.

586 individuals of Danish origin, 6673 of Western origin and 3757 of non-Western origin. Overall, OAC was initiated within −30/+90 days relative to the AF diagnosis in 50.3% of individuals of Danish origin initiated OAC, 49.6% of Western origin and 44.5% of non-Western origin. Immigrants from non-Western countries had significantly lower adjusted IRR of initiating OAC according to all ESC guidelines compared with patients of Danish origin. The adjusted IRRs ranged from 0.73 (95% CI: 0.66 to 0.80) following the launch of the 2010 ESC guideline to 0.89 (95% CI: 0.82 to 0.97) following the launch of the 2001 ESC guideline.

Conclusion

Patients with AF with a high risk of stroke of non-Western origin have persistently experienced a lower chance of initiating OAC compared with patients of Danish origin during the last decades.

Background

The number of immigrants has increased in Denmark as well as in Europe during the last decades and is projected to increase further due to conflicts, climate changes and economic factors, which will lead to greater ethnic and cultural diversity of populations.1 2 Inequality exists in general according to immigrants’ health status and in general and in relation to cardiovascular diseases.3–5

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia in Western countries. AF has a current prevalence of approximately 2% which is estimated to double by the year 2050.6 The prevalence may, however, be higher as cases of AF remain undiagnosed.7 Ischaemic stroke and systemic thromboembolism are well-known complications of AF. On average, the risk of stroke is increased fivefold.8 Oral anticoagulation (OAC) therapy is the primary preventive strategy for cardioembolic stroke in patients with AF. For decades, vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) were the only available OAC, but this changed with the introduction of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in 2011. The efficacy and safety of VKA and DOAC have been documented in clinical trials.9–13 According to European guidelines, patients with AF with a high risk of stroke should be treated with OAC. Still, the underuse of OAC has been a well-documented and persistent challenge in healthcare for decades.14

Social determinants of health, including ethnicity, may affect access to and quality of healthcare and OAC initiation has previously been investigated in relation to race in an American context.15–17 However, to our knowledge, no studies have investigated whether there are differences in OAC initiation between immigrant groups in a European setting.

Objectives

To examine whether OAC initiation differed for patients with incident AF with a high risk of stroke in relation to their country of origin.

Method

Setting and data sources

The study was conducted as a nationwide study in Denmark from the 1 May 1999 to 30 April 2017. The Danish healthcare system is primarily financed through taxation.18 Individuals with Danish citizenship or a long-term residency permit have free access to healthcare services, including hospital care and partial reimbursement of the costs of prescribed medicines. All Danish citizens have a personal identification number used in all public registers. This makes it possible to link data across all public registers and study the general population with relevant information concerning covariates.19 Only people who had lived in Denmark for at least 5 years were included to obtain data on comorbidity and socioeconomic position. Individuals were censored if they emigrated or died during the study period.

The following registers were used:

The Danish Civil Registrations System,20 which contains the date of birth, sex and country of birth.

The National Patient Register,21 which contains diagnoses, dates of admission and outpatient contact. The diagnoses are encoded using the International Classification of Diseases, 8th and 10th revision (ICD-10).

The Danish National Prescription Registry,22 which contains information about reimbursed drug prescriptions and uses the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system.

The Population Education Registry,23 which contains the highest completed educational level.

The Income Statistics Register,24 which contains income for individuals aged 15 or older at the end of the year and fully liable to pay tax in the year concerned. The income statistics mainly comprise wages and transfers. The captured income amounts, on average, to 90% of the total gross income.

The Employment Registry,25 which is an annual labour market statistic based on the population’s adherence to the labour market on the last working day in November.

Study population

The study population included patients with incident AF with a high risk of stroke from 01 May 1999 to 30 April 2017 at age 45 or older. AF was defined as a hospital diagnosis (ICD-10 code I48). We included AF diagnosed both at wards and in outpatient clinics. Furthermore, AF reported as a primary as well as a secondary diagnosis was included. Those diagnosed with AF before the study period were excluded.

The definition of a high risk of stroke changed throughout the study period according to the European guidelines issued by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in 1998, 2001, 2006, 2010 and 2012.26–30 For each guideline edition, we made a subpopulation defined according to the criteria of high risk of stroke used in the specific guideline (table 1). Because of the time to implement the guidelines, they were considered to be followed from the 1 May in the year following publication.31

Table 1

Criteria of high risk of stroke according to European Society of Cardiology guidelines

| Publication year | Time period in data | Criteria |

| 1998 | 01 May 1999 to 30 April 1999 Patient with incident AF, age ≥45 | High risk of stroke: More than one of the predisposing clinical factors: >65 years old, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, previous myocardial infarction, heart failure OR One high-risk factor: Prior stroke, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), systemic embolus |

| 2001 | 01 May 2002 to 30 April 2007 Patient with incident AF, age ≥45 |

One high-risk factor:

>75 years, hypertension, heart failure, prior thromboembolism OR >1 moderate risk factor: 65–75 years, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, thyrotoxicosis |

| 2006 | 01 May 2007 to 30 April 2011 Patient with incident AF, age ≥45 |

One high-risk factor:

Previous stroke, TIA, embolism, mitral stenosis, prosthetic heart valve OR >1 moderated risk factor: >75 years, hypertension, heart failure, diabetes mellitus |

| 2010 | 01 May 2011 to 30 April 2013 Patient with incident AF, age ≥45 | CHA2DS2-VASc>1 |

| 2012 | 01 May 2013 to 30 April 2017 Patient with incident AF, age ≥45 | CHA2DS2-VASc>1 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CHA2DS2-VASc, Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age (> 65 = 1 point, > 75 = 2 points), Diabetes, previous Stroke/transient ischemic attack (2 points).

Country of origin

The exposure of the study was country of origin, that is, Danish origin, Western origin and non-Western countries. The exposure was based on Statistics Denmark’s definition of country of origin and subdivision of Western and non-Western countries.32

Initiation of OAC

The initiation recommendation also changed through the study period and followed the guidelines definitions of high stroke risk. VKA were recommended in the guidelines published in 1998, 2001 and 2006. VKA or dabigatran was recommended in the 2010 guideline, and VKA, dabigatran, apixaban, edoxaban and rivaroxaban were recommended in the 2012 guideline. OAC initiation was defined as a redeemed prescription if it occurred between 30 days before and 90 days after the date the patient with AF entered a high risk of stroke and thereby the study population. Please see online supplemental table 20 for detailed information.

Supplementary data

Covariates

The covariates used in this study included sex, age, socioeconomic position, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA)/thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, antiplatelet drugs, coronary artery disease, thyrotoxicosis, major bleeding, renal disease, liver disease, peripheral artery disease (PAD)/aortic plaque and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) (see online supplemental table 20).

Socioeconomic position was assessed according to the level of education, income and adherence to the workforce. Data 5 years prior index date was included.

Education was defined according to the International Standard Classification of Education and the European consensus definitions as low, middle or high.33

Income was grouped into three categories relative to income in the population. Low income was below the lowest tertile, medium income was between the lowest and highest tertile and high income was the highest tertile.

Adherence to workforce was grouped as working, age-retirement or social subsidy. Adherence to workforce was defined by household level (best in the household).

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were presented as frequencies with percentages and continuous data were presented as medians with 25th–75th percentiles. For age, we implemented restricted cubic splines with three knots at quantiles 0.1, 0.5 and 0.9. Baseline characteristics were stratified by Danish origin, Western origin and non-Western origin.

The analyses were conducted using Poisson regression with an offset on the logarithm of the time from index to event or censoring, and the risk was estimated as incidence rate ratio (IRR). Due to missing data in relation to socioeconomic variables, we imputed data using multiple imputation chained equations which included covariates, exposure and the outcome represented by the outcome event proportion. We adjusted for covariates using doubly robust estimation for the matching parameters of sex and age.34 35 Because of changing guidelines criteria for high risk of stroke, we created five subpopulations and made five individual analyses with different adjustments in addition to an analysis of the total population (table 2). For the subpopulation based on ESC guideline in 1998, the adjustments were sex, age, educational level, income level, adherence to workforce, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, prior stroke/TIA/thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, antiplatelet drugs.

Table 2

Characteristics of the study population

| Danish origin | Western origin | Non-Western origin | |

| N=254 586 586 | N=6673 | N=3757 |

| Male | 132 529 (52%) 529 (52%) | 3019 (45%) | 1929 (51%) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 65 (56–73) | 64 (55–72) | 57 (48–65) |

| Educational level | |||

Low Low | 23 462 (11%) 462 (11%) | 1206 (24%) | 446 (19%) |

Middle Middle | 69 176 (32%) 176 (32%) | 1839 (37%) | 652 (28%) |

High High | 120 694 (57%) 694 (57%) | 1916 (39%) | 1206 (52%) |

| Income level | |||

Low Low | 171 809 (68%) 809 (68%) | 4261 (65%) | 2754 (74%) |

Middle Middle | 60 196 (24%) 196 (24%) | 1673 (25%) | 756 (20%) |

High High | 21 235 (8%) 235 (8%) | 634 (10%) | 196 (5%) |

| Work adherence | |||

Work Work | 47 593 (19%) 593 (19%) | 1182 (18%) | 559 (15%) |

Retired Retired | 194 498 (76%) 498 (76%) | 4718 (71%) | 1972 (53%) |

Social subsidy Social subsidy | 12 385 (5%) 385 (5%) | 725 (11%) | 1187 (32%) |

| Hypertension | 215 351 (85%) 351 (85%) | 5587 (84%) | 3220 (86%) |

| Diabetes | 37 744 (15%) 744 (15%) | 1037 (16%) | 1281 (34%) |

| Myocardial infarction | 26 301 (10%) 301 (10%) | 684 (10%) | 561 (15%) |

| Heart failure | 31 618 (12%) 618 (12%) | 856 (13%) | 621 (17%) |

| Ischaemic stroke | 15 932 (6%) 932 (6%) | 410 (6%) | 220 (6%) |

| TIA | 13 143 (5%) 143 (5%) | 352 (5%) | 140 (4%) |

| PAD/aortic plaque | 8315 (3%) | 219 (3%) | 77 (2%) |

| Major bleeding | 35 825 (14%) 825 (14%) | 990 (15%) | 753 (20%) |

| Abnormal renal function | 11 090 (4%) 090 (4%) | 267 (4%) | 283 (8%) |

| Abnormal liver function | 920 (0%) | 30 (0%) | 17 (0%) |

| Systemic embolism | 1786 (1%) | 38 (1%) | 18 (0%) |

PAD, peripheral artery disease; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

For the subpopulation based on ESC guideline in 2001, the adjustments were sex, age, educational level, income level, adherence to workforce, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, prior stroke/TIA/thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, antiplatelet drugs and thyrotoxicosis.

For the subpopulation based on ESC guideline in 2006, the adjustments were sex, age, educational level, income level, adherence to workforce, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, prior stroke/TIA/thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, antiplatelet drugs, thyrotoxicosis and coronary artery disease.

For the subpopulation based on ESC guideline in 2011 and 2013, the adjustments were sex, age, educational level, income level, adherence to workforce, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, prior stroke/TIA/thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, antiplatelet drugs, major bleeding, renal disease, liver disease, PAD/aortic plaque and NSAID. All analyses had patients of Danish origin as reference.

As a supplement, all analyses were stratified by sex and age groups (below 65, 65–74 and above 74 years).

We used Stata V.16 (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, Texas, USA: StataCorp LLC), and all results were presented with 95% CIs.

Results

The population contained 254 586 patients with incident AF of Danish origin, 6673 of Western origin and 3757 of non-Western origin. A total of 127

586 patients with incident AF of Danish origin, 6673 of Western origin and 3757 of non-Western origin. A total of 127 983 individuals of Danish origin with a high risk of stroke were treated according to the valid guidelines during the study period. For individuals of Western origin, the number was 3309 and for individuals of non-Western origin, the number was 1672. Please see online supplemental tables 1 and 2 for absolute numbers.

983 individuals of Danish origin with a high risk of stroke were treated according to the valid guidelines during the study period. For individuals of Western origin, the number was 3309 and for individuals of non-Western origin, the number was 1672. Please see online supplemental tables 1 and 2 for absolute numbers.

For the total population of patients with incident AF with a high risk of stroke, the unadjusted IRR was lower for patients from non-Western countries compared with patients of Danish origin (0.82 (95% CI: 0.79 to 0.85)) whereas no difference was observed for patients from Western countries (0.98 (95% CI: 0.96 to 1.00)) See figure 1.

Adjusted IRRs of oral anticoagulation initiation according to origin for specific guidelines. Danish origin is the reference. IRR, incidence rate ratio.

When investigating the implementation of the different editions of the guidelines, a lower chance of OAC initiation was consistently indicated for patients of non-Western origin compared with patients of Danish origin in all periods. The IRR estimates were consistent during the guidelines as patients with AF with a high risk of stroke from non-Western countries had significantly lower IRR estimates regarding OAC treatment compared with patients of Danish origin. Hence, the adjusted IRR for the most recent population, reflecting the ESC guideline from 2012 was 0.75 (95% CI: 0.63 to 0.88) when comparing immigrants from non-Western countries to patients of Danish origin. Online supplemental tables 3–9 show unadjusted results.

No overall statistically significant differences in OAC use were observed among patients with AF with a high risk of stroke from Western countries when compared with patients of Danish origin.

Focusing on the potential difference in the use of DOAC and VKA following the publication of the guideline from 2012, separate analyses for DOAC and VKA were performed. The IRRs for DOAC treatment were 1.06 (95% CI: 1.01 to 1.12) and 0.95 (95% CI: 0.89 to 1.01) for immigrants from Western and non-Western countries, respectively, indicating no differences in use according to country of origin. In contrast, the IRRs for VKA use were 0.75 (95% CI: 0.67 to 0.84) and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.80 to 0.95) for immigrants from Western and non-Western countries, respectively.

Results stratified by sex and age groups were in line with the primary analyses (online supplemental tables 8–19).

Discussion

In this nationwide register-based study of patients with AF with a high risk of stroke, patients of non-Western counties had a lower chance of OAC initiation than patients of Danish origin. The difference appears to have been present across multiple editions of the ESC guidelines during the last decades. In contrast, the chance of OAC initiation for patients of Western origin did not differ statistically significantly from patients of Danish origin.

There is a paucity of European data on OAC initiation among immigrants and the host population with AF. However, a previous Danish study of OAC initiation following ischaemic stroke found no major differences between individuals of Danish origin and immigrants.36 The contrast to our study may be in the study population as the earlier study was restricted to patients with AF who had been hospitalised with an acute stroke and treated in the specialised stroke unit. The management of patients who had a stroke in Denmark is centralised in large hospital departments in Denmark and the quality of care, including post-stroke treatment with OAC, is systematically monitored through a nationwide clinical quality database. Therefore, it might be expected that the application of OAC shows less variation in this study population compared with all patients with AF, who are treated in many different settings in the healthcare systems.

Studies from the USA investigating race and initiation of OAC in patients with AF also found inequalities: A study based on Medicare beneficiaries from 2013 to 2014 found that blacks were less likely than whites to initiate OAC with an adjusted OR of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.78 to 0.91).16 A similar study based on a voluntary quality improvement initiative with data from 2014 to 2020 also found that black patients were less likely than white patients to be discharged while taking any anticoagulant with adjusted OR: 0.75 (95% CI: 0.68 to 0.84).17 Finally, a study based on the Veterans Health Administration Corporate Data Warehouse data and Medicare data from 2010 to 2018 found that black patients had lower initiation of any anticoagulant with adjusted OR: 0.89 (95% CI: 0.82 to 0.97).15 Furthermore, a Danish study investigating patients with post-acute coronary syndrome found lower initiation of relevant treatment in patients with non-Western origin compared with patients of Danish origin.37 Also, a study made in Sweden, which has a healthcare system similar to the Danish, investigated treatment according to guidelines for acute myocardial infarction found that inequality existed between immigrants and patients of Swedish origin.38

Further efforts are needed in order to clarify the causes of the observed differences in the initiation of OAC. Since the number of immigrants is increasing, the public health and clinical implications of persistently lower rate of OAC use will automatically increase if nothing is done given the well-documented preventive effect of OAC on both ischaemic stroke risk and severity. Furthermore, OAC treatment has a beneficial effect on patients who experience a stroke while they are receiving OAC since they experience milder strokes compared with patients who had a stroke not receiving OAC treatment.39

All patients included in our study fulfilled the guideline-recommended eligibility criteria for OAC treatment as far as it is possible to define these criteria using administrative register data. However, it is not possible, based on the available data, to determine whether the lower chance of OAC initiation among non-Western patients was due to a lower willingness/attention among physicians to prescribe OAC or a barrier among the patients to redeem issued prescriptions. The physician may be uncertain about the compliance of the patient and potentially perceive that the risk profile of the patient has not been sufficiently clarified, for example, due to language barriers. From the patient’s perspective, poor health literacy may partly explain why some patients do not claim their prescribed medication.40 Additionally, the financial status of the patient could influence if the patient claims medication since it is partly self-payment, but since we adjusted for income level, this should not be an explanation for our findings. Another factor is patient preferences, which we do not have data on. It could partly reflect health literacy, but the overlap is not complete. Some patients want to avoid receiving recommended medical treatment even though they are fully capable of cognitively understanding the implications of this opt-out.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was the nationwide register data, resulting in a large sample size and almost complete follow-up.21 Also, we stratified patients with a high risk of stroke according to the guidelines and adjusted for what could influence the OAC initiation for each specific guideline.

Since the OAC initiation of this study was measured according to registers, we cannot know if the doctor did not give the OAC initiation or if the patient did not redeem their prescription. Further, the criteria for high risk of stroke has been criticised, since there is no evidence for thresholds for age according to risk of stroke.41 However, this does not change the fact that we were able to assess if the official guidelines were followed or not. The Danish population is still quite homogeneous and the absolute number of immigrants with AF is still low. This made it impossible to achieve meaningful statistical precision in more detailed analyses, for example, analyses based on comparison of populations of specific countries of origin.

Finally, although the data completeness in general was high, data on educational level might not be fully complete since old educations are not included in the register and educations from foreign countries might not be fully captured.

Conclusion

Patients with incident AF and a high risk of stroke of non-Western origin had a lower chance of OAC initiation compared with patients of Danish origin and the difference in treatment practice appeared persistent across multiple editions of the ESC guidelines on AF. Further efforts are warranted in order to determine the extent, causes and implications of potential disparity in AF care among immigrant populations.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception of the study and approved the final manuscript. JF is acting as guarantor.

Funding: The study was funded by Karen Elise Jensen’s Foundation who had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis or writing of this manuscript.

Disclaimer: LF supported by the Health Research Foundation of Central Denmark Region, consultant for BMS/Pfizer and AstraZeneca.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data are available from Statistics Denmark, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Statistics Denmark.

References

Articles from Open Heart are provided here courtesy of BMJ Publishing Group

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Disparities in oral anticoagulation initiation in patients with schizophrenia and atrial fibrillation: A nationwide cohort study.

Br J Clin Pharmacol, 88(8):3847-3855, 08 Apr 2022

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 35355307 | PMCID: PMC9545247

Incidence of atrial fibrillation and flutter in Denmark in relation to country of origin: a nationwide register-based study.

Scand J Public Health, 14034948231205822, 05 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38179955

Flaws in Anticoagulation Strategies in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation at Hospital Discharge.

J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther, 24(3):225-232, 01 Jan 2019

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 30599759

Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation associated with valvular heart disease: a joint consensus document from the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, endorsed by the ESC Working Group on Valvular Heart Disease, Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), South African Heart (SA Heart) Association and Sociedad Latinoamericana de Estimulación Cardíaca y Electrofisiología (SOLEACE).

Europace, 19(11):1757-1758, 01 Nov 2017

Cited by: 56 articles | PMID: 29096024

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

1

1