Abstract

Aims

Anticoagulation can prevent stroke and prolong lives in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). However, anticoagulated patients with AF remain at risk of death. The aim of this study was to investigate the causes of death and factors associated with all-cause and cardiovascular death in the XANTUS population.Methods and results

Causes of death occurring within a year after rivaroxaban initiation in patients in the XANTUS programme studies were adjudicated by a central adjudication committee and classified following international guidance. Baseline characteristics associated with all-cause or cardiovascular death were identified. Of 11 040 patients, 187 (1.7%) died. Almost half of these deaths were due to cardiovascular causes other than bleeding (n = 82, 43.9%), particularly heart failure (n = 38, 20.3%) and sudden or unwitnessed death (n = 24, 12.8%). Fatal stroke (n = 8, 4.3%), which was classified as a type of cardiovascular death, and fatal bleeding (n = 17, 9.1%) were less common causes of death. Independent factors associated with all-cause or cardiovascular death included age, AF type, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, hospitalization at baseline, rivaroxaban dose, and anaemia.Conclusion

The overall risk of death due to stroke or bleeding was low in XANTUS. Anticoagulated patients with AF remain at risk of death due to heart failure and sudden death. Potential interventions to reduce cardiovascular deaths in anticoagulated patients with AF require further investigation, e.g. early rhythm control therapy and AF ablation.Trial registration numbers

NCT01606995, NCT01750788, NCT01800006.Free full text

Causes of death in patients with atrial fibrillation anticoagulated with rivaroxaban: a pooled analysis of XANTUS

Abstract

Aims

Anticoagulation can prevent stroke and prolong lives in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). However, anticoagulated patients with AF remain at risk of death. The aim of this study was to investigate the causes of death and factors associated with all-cause and cardiovascular death in the XANTUS population.

Methods and results

Causes of death occurring within a year after rivaroxaban initiation in patients in the XANTUS programme studies were adjudicated by a central adjudication committee and classified following international guidance. Baseline characteristics associated with all-cause or cardiovascular death were identified. Of 11 040 patients, 187 (1.7%) died. Almost half of these deaths were due to cardiovascular causes other than bleeding (n = 82, 43.9%), particularly heart failure (n = 38, 20.3%) and sudden or unwitnessed death (n = 24, 12.8%). Fatal stroke (n = 8, 4.3%), which was classified as a type of cardiovascular death, and fatal bleeding (n = 17, 9.1%) were less common causes of death. Independent factors associated with all-cause or cardiovascular death included age, AF type, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, hospitalization at baseline, rivaroxaban dose, and anaemia.

Conclusion

The overall risk of death due to stroke or bleeding was low in XANTUS. Anticoagulated patients with AF remain at risk of death due to heart failure and sudden death. Potential interventions to reduce cardiovascular deaths in anticoagulated patients with AF require further investigation, e.g. early rhythm control therapy and AF ablation.

Trial registration numbers

NCT01606995, NCT01750788, NCT01800006

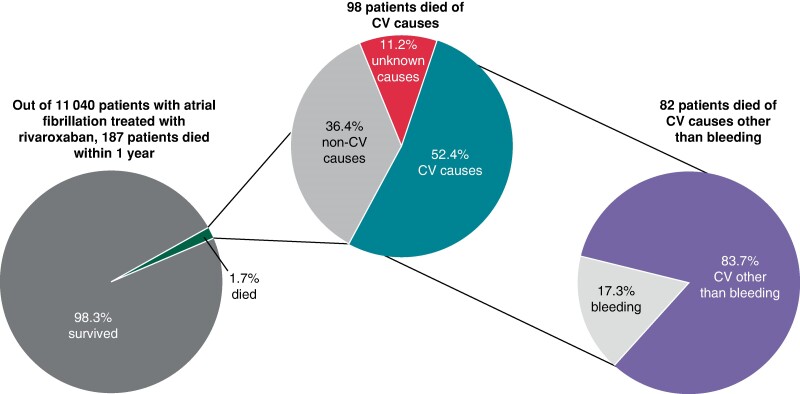

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract

Adjudicated causes of death in the XANTUS programme. Patients with atrial fibrillation treated with rivaroxaban were enrolled and followed up for 12 months. All deaths were centrally adjudicated. The majority of deaths was cardiovascular, with deaths due to heart failure and sudden deaths the most common causes of death. The findings call for additional interventions, e.g. early rhythm control, to reduce the burden of death due to heart failure and sudden death.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with increased mortality,1,2 and stroke is a common cause of death in patients with AF.3,4 Oral anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists or non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) can reduce the risk of stroke as well as mortality in patients with AF.3,5 However, even when receiving anticoagulation therapy, patients with AF enrolled into controlled clinical trials remain at risk of cardiovascular death, calling for further treatments to improve outcomes.6–8

The XANTUS programme collected 1-year outcomes in more than 11 000 unselected patients with AF from 47 countries who were anticoagulated with the NOAC rivaroxaban.9,10 Centrally adjudicated causes of death and a description of factors associated with all-cause death and cardiovascular death in the XANTUS population are reported.

Methods

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

The XANTUS programme has been described previously. This analysis included data from the XANTUS (NCT01606995), XANTUS-EL (NCT01800006), and XANAP (NCT01750788) studies.11–13 These three observational studies included patients with AF treated with rivaroxaban. Follow-up was planned for 1 year. To enable the capture of a wide range of patients receiving rivaroxaban in clinical care, hardly any exclusion criteria were stipulated, and sites were encouraged to enrol consecutive patients. All causes of death in patients with AF in the first year after initiating rivaroxaban therapy were adjudicated by a central adjudication committee. A single committee consisting of five members adjudicated all events across the prospective, observational XANTUS programme,10 which enrolled patients from different geographic regions (XANTUS: Western Europe, Canada, and Israel;11 XANAP: Asia Pacific;12 XANTUS-EL: the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Africa, and Latin America13). Each event was independently adjudicated by two adjudication committee members, and a third member was involved if there was any disagreement. All patients included in the analysis provided informed, written consent.

The main outcomes of interest in this analysis were all-cause death and cardiovascular death. Cardiovascular death included death due to intracranial and extracranial bleeding, stroke, and other cardiovascular causes, as listed in Table Table11; other XANTUS outcomes were defined in previous publications.11–13 Non-cardiovascular death included death due to cancer, infectious disease, or other known causes (Table Table11). For some patients, multiple causes of death were adjudicated. If one of these causes was cardiovascular, the death was categorized as ‘cardiovascular death’. If the cause of death was ‘other’ with a non-cardiovascular cause specified, the death was categorized as non-cardiovascular, and if no further specification was given, the death was categorized as ‘unknown’ (Figure Figure11).

Table 1

Summary of causes of death

| Category, n (%) | Adjudicated cause of death | Number of patients who died (n = 187), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular death, 98 (52.4)a | Bleeding | 17 (9.1) |

| Extracranial haemorrhage | 6 (3.2) | |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | 11 (5.9) | |

| Cardiovascular other than bleeding | 82 (43.9)b | |

| Cardiac decompensation/heart failure | 38 (20.3) | |

| Sudden or unwitnessed deathc | 24 (12.8) | |

| Myocardial infarction | 8 (4.3) | |

| Non-haemorrhagic stroke | 8 (4.3) | |

| Other vascular event | 3 (1.6) | |

| Dysrhythmia | 2 (1.1) | |

| Venous thromboembolism | 1 (0.5) | |

| Systemic embolism | 0 (0) | |

| Non-cardiovascular death, 68 (36.4)a | Cancer | 26 (13.9) |

| Infectious disease | 24 (12.8) | |

| Other (reason specified)d | 23 (12.3) | |

| Unknown, 21 (11.2)a | Other (no reason given) | 3 (1.6) |

| Unexplainede | 22 (11.8) |

CV, cardiovascular.

aA patient could have more than one adjudicated cause of death but could only be included in one of the categories of cardiovascular death, non-cardiovascular death, and unknown.

bTwo patients had two cardiovascular causes of death (other than bleeding) each.

cSudden or unwitnessed deaths were assessed as cardiovascular deaths.

dReasons included respiratory, renal, and multi-system failure.

eOf the 22 patients with unexplained causes of death, one had an additional cardiovascular cause of death and was included in the cardiovascular death category.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed using the Statistical Analysis System (release 9.2 or higher). All patients who received at least one dose of rivaroxaban during the observation period were analysed. One site with Good Clinical Practice violations in the XANTUS study was excluded from the analysis (81 patients were affected). Cumulative incidence functions for cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular deaths were calculated using the Aalen–Johansen estimator. Other causes of death were considered as competing risks for the respective curve.14

In addition, an analysis to determine baseline characteristics associated with all-cause death and cardiovascular death was performed. For each outcome, the analysis was conducted in the following steps. First, a descriptive analysis of potential factors associated with outcomes was performed based on medical judgement and previous reports in the literature. Secondly, univariate Cox models were fitted with the outcome as the response variable and only one feature at a time. Features with a P-value <0.10 were candidates for inclusion in the multivariable model, and Kendall's Tau was used to assess correlations between covariates. Factors that were categorized and had very low numbers of events in a category were excluded or combined with another category. The proportional hazards assumption of the covariates was checked. In the third step, multivariable Cox regression models, including the previously selected factors, were fitted using backward elimination. At each stage, the variable with the highest P-value was excluded from the model until all variables in the model were significant (P < 0.10). Finally, discrimination in the multivariable models was assessed using Harrell's C statistic.15 Because data on creatinine clearance (CrCl) were missing in 37% of patients, these patients were grouped with patients who had CrCl ≥ 50 mL/min. These two groups had similar baseline characteristics and were generally healthier than patients with CrCl < 50 mL/min. A sensitivity analysis, from which patients with missing CrCl values were excluded, was also performed.

Results

Of 11 040 patients receiving rivaroxaban treatment for a median duration of 366 (interquartile range 329–379) days, the majority survived (10 853, 98.3%), 187 (1.7%) died, and 87 fatal or non-fatal strokes and 172 fatal or non-fatal major bleeding events occurred; these were defined in line with previous XANTUS publications.11,12,16 The mean age of the population of patients who survived was 70.4 ± 10.4 years, and 76.7 ± 10.4 years in the population who died. The mean CHA2DS2-VASc [congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, stroke or transient ischaemic attack (2 points), vascular disease, age 65–74, sex category (female)] score was 3.5 ± 1.7 in the survival population and 4.4 ± 1.7 in the population who died.

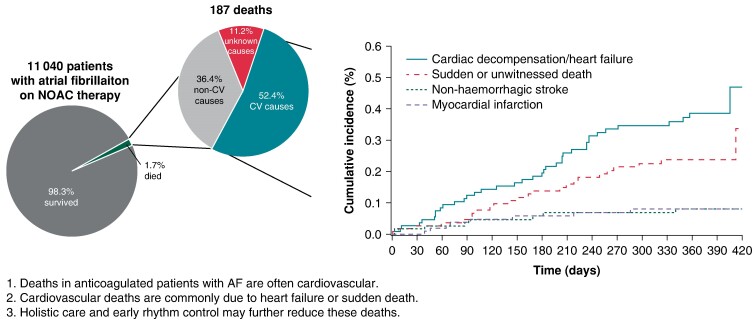

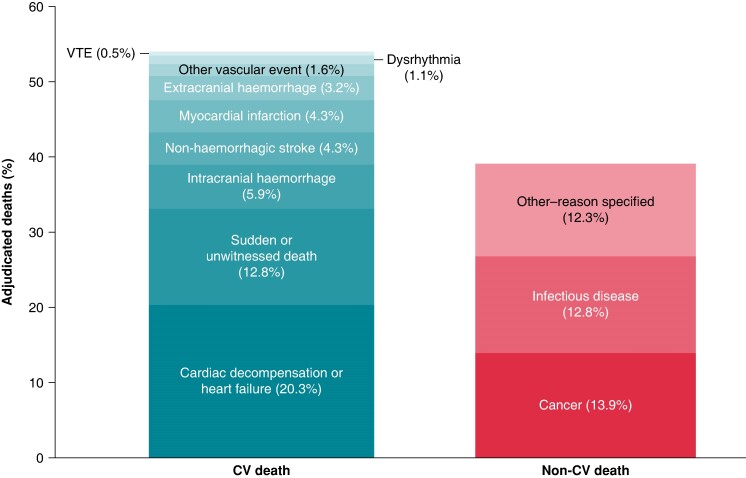

Among the patients who died, 98 (52.4%) died of cardiovascular causes [1.0 event per 100 patient-years; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.8–1.2], 68 (36.4%) died of other causes (0.7 events per 100 patient-years; 95% CI 0.5–0.9), and the remaining 21 (11.2%) died of unknown causes (0.2 events per 100 patient-years; 95% CI 0.1–0.3; Table Table11, Figures Figures22 and 33). Deaths occurred at a steady rate during the 1-year follow-up period (Figure Figure33). Deaths were most often due to heart failure (n = 38), sudden or unwitnessed death (n = 24), cancer (n = 26), or infectious diseases (n = 24). Causes of death in the subcategory other (n = 23) included respiratory, renal, and multi-system failure.

Causes of death in the pooled XANTUS studies. A patient could have more than one adjudicated cause of death but could only be included in one of the categories of cardiovascular death or non-cardiovascular death. CV, cardiovascular; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

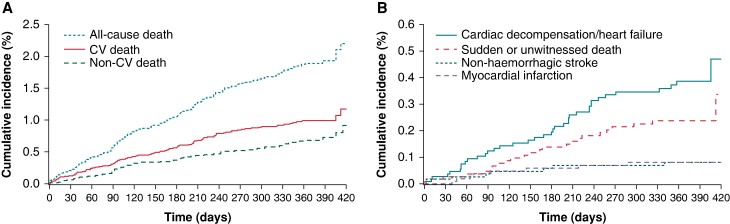

Cumulative incidence of death according to (A) cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular death and (B) sudden or unwitnessed death, and death due to non-haemorrhagic stroke, myocardial infarction, or cardiac decompensation or heart failure. Aalen–Johansen estimates are shown for the cumulative incidence functions, including all other deaths as competing risks. For all-cause death, Kaplan–Meier estimates are shown. CV, cardiovascular.

Compared with survivors, patients who died were older, with a lower body mass index (BMI), and were more likely to suffer from persistent forms of AF and to have a history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack or non-central nervous system systemic embolism, heart failure, diabetes, or myocardial infarction (MI; Table Table22). In addition, patients who died were more often hospitalized at baseline and, if enrolled as outpatients, more often managed by general physicians. They were also more often anaemic or treated with doses other than those recommended in the label. Baseline characteristics were generally more similar between patients who died of cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular causes compared with those with unknown causes of death (Table (Table2).2). Patient sex, dosing according to label, AF type, hypertension, prior MI, active cancer at baseline, and type of treating physician differed according to the cause of death.

Table 2

Baseline characteristics according to survival

| Potential risk factor | Patients who survived (n = 10 853) | Patients who died (n = 187) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 70.4 ± 10.4 | 76.7 ± 10.4 | <0.0001 |

| Age, years | <0.0001 | ||

<75 <75 | 6712 (61.8) | 70 (37.4) | |

≥75 ≥75 | 4141 (38.2) | 117 (62.6) | |

| Male | 6207 (57.2) | 101 (54.0) | 0.3811 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, mean ± SD | 3.5 ± 1.7 | 4.4 ± 1.7 | <0.0001 |

| HAS-BLED score, mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | <0.0001 |

| Rivaroxaban dose | <0.0001 | ||

20 mg o.d. 20 mg o.d. | 7997 (73.7) | 102 (54.5) | |

15 mg o.d. 15 mg o.d. | 2665 (24.6) | 76 (40.6) | |

Other doses (including missing)a Other doses (including missing)a | 191 (1.8) | 9 (4.8) | |

| Dosing according to label | <0.0001 | ||

Yes Yes | 5397 (49.7) | 83 (44.4) | |

No No | 1518 (14.0) | 48 (25.7) | |

Unknownb Unknownb | 3938 (36.3) | 56 (29.9) | |

| First available CrCl, mL/min, median (IQR) | 68.8 (55.1–87.0) | 60.0 (42.0–71.0) | 0.3350 |

| First available CrCl | <0.0001 | ||

<50 mL/min <50 mL/min | 1215 (11.2) | 47 (25.1) | |

≥50 mL/min ≥50 mL/min | 5647 (52.0) | 82 (43.9) | |

Unknown Unknown | 3991 (36.8) | 58 (31.0) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 28.0 ± 5.1 | 27.0 ± 6.3 | 0.0232 |

| First available weight, kg, mean ± SD | 80.0 ± 17.7 | 75.6 ± 20.0 | 0.0021 |

| AF type | <0.0001 | ||

First diagnosed First diagnosed | 1997 (18.2) | 41 (21.9) | |

Paroxysmal Paroxysmal | 4066 (37.5) | 36 (19.3) | |

Persistent Persistent | 1756 (16.2) | 40 (21.4) | |

Permanent Permanent | 3012 (27.8) | 69 (36.9) | |

Missing Missing | 42 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Prior stroke/TIA/non-CNS SE | 2274 (21.0) | 55 (29.4) | 0.0049 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2276 (21.0) | 76 (40.6) | <0.0001 |

LVEF LVEF | <0.0001 | ||

<40% <40% | 1075 (9.9) | 45 (24.1) | |

≥40% ≥40% | 8619 (79.4) | 105 (56.1) | |

Unknownb Unknownb | 1159 (10.7) | 37 (19.8) | |

| Hypertension | 8262 (76.1) | 143 (76.5) | 0.9128 |

| Diabetes | 2405 (22.2) | 57 (30.5) | 0.0067 |

| Prior MI | 956 (8.8) | 29 (15.5) | 0.0014 |

| Vascular disease | 2964 (27.3) | 67 (35.8) | 0.0097 |

| Active cancer at baseline | 129 (1.2) | 6 (3.2) | 0.0127 |

| Anaemia/reduced haemoglobin | 346 (3.2) | 24 (12.8) | <0.0001 |

| Hospitalized at baseline | <0.0001 | ||

Yes Yes | 2004 (18.5) | 60 (32.1) | |

No No | 8848 (81.5) | 127 (67.9) | |

Missing Missing | 1 (<0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Patient treated by | 0.0040 | ||

GP GP | 668 (6.2) | 13 (7.0) | |

Office cardiologist Office cardiologist | 5388 (49.6) | 76 (40.6) | |

Office neurologist Office neurologist | 218 (2.0) | 4 (2.1) | |

In-hospital physician In-hospital physician | 4438 (41) | 88 (47.1) | |

Other Other | 140 (1.3) | 6 (3.2) | |

Missing Missing | 1 (<0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Prior antithrombotic therapy | 0.6100 | ||

Yes Yes | 7413 (68.3) | 131 (70.1) | |

No No | 3440 (31.7) | 56 (29.9) | |

| Concomitant antiplatelet or NSAID | 0.7721 | ||

Yes Yes | 2285 (21.1) | 41 (21.9) | |

No No | 8568 (78.9) | 146 (78.1) | |

| Alcohol use | 0.0002 | ||

Abstinent Abstinent | 5830 (53.7) | 124 (66.3) | |

Light Light | 3952 (36.4) | 47 (25.1) | |

Medium or heavy Medium or heavy | 878 (8.1) | 10 (5.3) | |

Missing Missing | 193 (1.8) | 6 (3.2) | |

| Smoking | 0.6081 | ||

Never Never | 6956 (64.1) | 114 (61.0) | |

Former Former | 3056 (28.2) | 58 (31.0) | |

Current Current | 698 (6.4) | 11 (5.9) | |

Missing Missing | 143 (1.3) | 4 (2.1) |

Values are n (%) unless specified otherwise.

AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CHA2DS2-VASc, Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 years (2 points), Diabetes mellitus, Stroke or transient ischaemic attack (2 points), Vascular disease, age 65–74 years, Sex category (female); CNS, central nervous system; CrCl, creatinine clearance; GP, general practitioner; HAS-BLED, Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile international normalized ratio, Elderly, Drugs/alcohol concomitantly; IQR, interquartile range; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NSAID, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug; od, once daily; SD, standard deviation; SE, systemic embolism; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

aThree patients had missing doses, 190 patients received doses <15 mg o.d., and 7 patients received doses >20 mg o.d.

bThese missing values were included in the category ‘unknown’ in the multivariable Cox regression model.

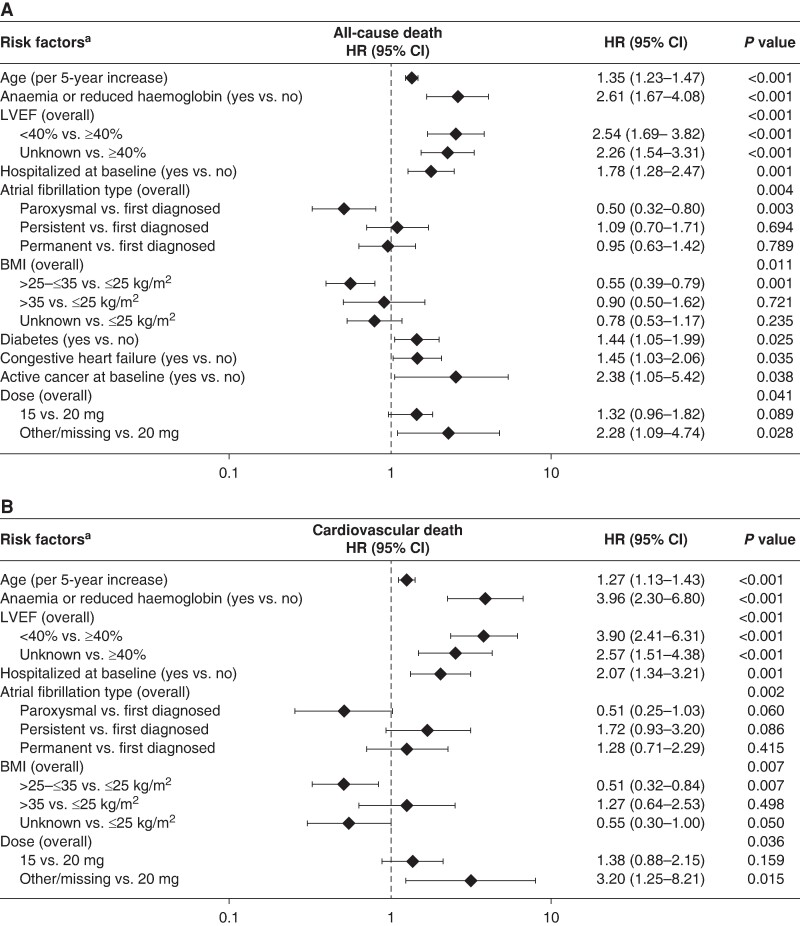

Factors associated with all-cause death and cardiovascular death were selected from the available baseline characteristics using Cox proportional hazards regression and included in the multivariable Cox regression model. The multivariable Cox regression models are shown in Figure Figure44. This exploratory analysis suggested that age, anaemia, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), hospitalization at baseline, AF type, BMI, diabetes, congestive heart failure, active cancer, and rivaroxaban dose independently affected the risk of all-cause death. Similarly, age, anaemia, or reduced haemoglobin, LVEF, hospitalization at baseline, AF type, BMI, and rivaroxaban dose were independently associated with cardiovascular death. A sensitivity analysis assessing the effect of excluding patients with missing CrCl values showed generally similar results (data not provided).

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression of risk factors for (A) all-cause death and (B) cardiovascular death. CV, cardiovascular. aHarrell's C statistic was 0.782 for A and 0.798 for B. BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; HR, hazard ratio, LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. First-diagnosed AF was chosen as a comparator as it reflects the first presenting pattern of AF.

Discussion

This study explored the causes of death in patients with AF anticoagulated with rivaroxaban in routine care. Overall, mortality was low. Cardiovascular death, especially due to heart failure and sudden or unwitnessed death, was the most common cause of death and accounted for nearly half of deaths, comparable with reports from the Global Anticoagulant Registry in the FIELD Atrial Fibrillation (GARFIELD-AF).17 Deaths due to stroke were uncommon, as were deaths due to bleeding (Table Table11, Figure Figure33). Several factors were independently associated with an increased risk of all-cause or cardiovascular death. These factors included age, AF pattern, LVEF, hospitalization at baseline, rivaroxaban dose, and comorbidities such as anaemia or reduced haemoglobin, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and active cancer.

The association of heart failure with an increased risk of death observed in our analysis is of particular interest. Similar results have been reported in other studies. In the prospective GARFIELD-AF Registry,2 approximately half of deaths were due to cardiovascular causes, and congestive heart failure and cancer were the two most common causes of death overall, whereas sudden or unwitnessed death was the second most common cause of cardiovascular death. Congestive heart failure and other characteristics, such as diabetes and older age, were also associated with an increased risk of death.2 In several contemporary observational data sets, including the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation,18 the Global Registry on Long-Term Oral Anti-thrombotic Treatment In Patients With Atrial Fibrillation, the EURObservational Research Programme in Atrial Fibrillation, and the Fushimi AF Registry,19–21 and in a French retrospective database study22 and the Loire Valley study,23,24 it was found that the presence of heart failure and other comorbidities increased the risk of cardiovascular death. To reduce AF-related mortality, it is important for clinicians to treat comorbid conditions alongside heart failure and any anticoagulation.20,25 Subanalyses of the EAST-AFNET 4 trial26 and recent trials of AF ablation27 all support the early use of rhythm control therapy and AF ablation in patients with AF and heart failure. It is possible that a more intensive and earlier use of rhythm control could have reduced sudden deaths and heart failure–related deaths in this population.

The Phase III NOAC trials also found a high rate of death due to heart failure or sudden death: In the Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48) trial, the most common cause of cardiovascular death was sudden cardiac death, the risk of which was increased in patients with low ejection fraction, heart failure, or prior MI at baseline.28 The rate of fatal bleeding observed here is comparable with findings in the approval trials of the NOACs28,29 and in recent controlled trials of NOACs in patients with device-detected AF.30,31 A meta-analysis of the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation, RE-LY, ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48, and Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF) studies also showed that the most common causes of death were sudden death or dysrhythmia and heart failure, with fatal bleeding or ischaemic stroke being the cause of death in only a small proportion of patients.29 Finally, a meta-analysis of these Phase III trials showed that patients with heart failure and AF had an increased risk of death, a lower risk of bleeding, and a similar risk of stroke or systemic embolism compared with patients who did not have heart failure, whereas the efficacy and safety of NOACs vs. warfarin treatment were similar regardless of comorbid heart failure.32 Overall, our data support the notion that death due to heart failure and sudden death are the main drivers of mortality in anticoagulated patients with AF.

The evidence that patients with AF remain at risk of death despite anticoagulation, as well as the evidence that causes of death other than stroke play an important role in the risk of mortality in AF, contributed to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society guideline recommendations for a more holistic and integrated approach to care with the Atrial Fibrillation Better Care (ABC) pathway.25,33 This pathway has three key components: avoid stroke, better symptom control, and treatment of comorbidities.25,33 The recently published ACC/AHA/HRS guidelines on AF add a new therapeutic goal to the management of AF: reduction of AF burden.34 A call for a broader use of rhythm control also came out of the 9th AFNET/EHRA consensus document.35 Our data illustrate the potential for rhythm control interventions, and for holistic AF care, to further reduce cardiovascular events in anticoagulated patients with AF.

Events in XANTUS underwent a similar adjudication process as events in controlled clinical trials, rendering causes of death comparable. Mortality in XANTUS was lower than in historic cohorts of patients with AF not receiving anticoagulation.36–38 In addition, we observed very few deaths due to stroke or bleeding, underpinning the efficacy and safety of NOACs, such as rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in patients with AF.29 Despite this effect, which can be attributed to anticoagulation, cardiovascular deaths due to heart failure or sudden, presumably arrhythmic death remained common.

The association of anaemia or low haemoglobin at baseline with all-cause death and cardiovascular death is also of interest. Anaemia was four times more frequent at baseline in patients who died (n = 24, 12.8%) compared with survivors (n = 346, 3.2%), and there was a trend towards a higher frequency of anaemia in patients who died of cardiovascular (n = 17, 17.3%) vs. non-cardiovascular causes (n = 7, 10.3%). Previously, low haemoglobin levels were identified as a predictor of death and hospitalization for heart failure in patients with AF in a prospective, single-centre cohort study,39 and anaemia was a predictor of death and rehospitalization in a US claims database analysis of elderly patients with AF.40 In addition to heart failure, death due to bleeding, and death due to non-cardiovascular causes associated with anaemia, such as cancer, may have contributed to these trends. Our cohort is too small to draw a conclusion on this topic. Of the 24 patients with anaemia or reduced haemoglobin at baseline who died, the most common adjudicated cause of death was cardiac decompensation or heart failure (n = 11). Cancer (n = 2), intracranial haemorrhage (n = 1), and extracranial haemorrhage (n = 1) were identified as the adjudicated cause of death in very few of these patients. The remainder of these patients died of infectious disease (n = 3), non-haemorrhagic stroke (n = 2), multi-organ failure (n = 1), MI (n = 1), respiratory failure (n = 1), or sudden or unwitnessed death (n = 1). The effect of investigating or treating anaemia in patients with AF on the risk of mortality requires further study. Our results highlight that low haemoglobin levels can help to identify patients with AF at risk.

The identification of rivaroxaban dose as a feature associated with death and cardiovascular death is probably linked to measured and unmeasured underlying comorbidities and their real or perceived severity. This is especially true for patients with malignancies. The fact that a proportion of patients did not receive the indicated dose of rivaroxaban is discussed in full in the original XANTUS publication10 and will, therefore, not be covered in detail here.

To further reduce the risk of death in patients with AF, treatments other than anticoagulation are needed. Our exploratory analysis suggested that targeting heart failure, sudden death, and AF could improve survival in this setting. The recently published Early Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation for Stroke Prevention Trial (EAST-AFNET 4)41 and its subanalyses26,42,43 suggest that early rhythm control therapy could reduce cardiovascular complications, including cardiovascular death, in anticoagulated patients with recently diagnosed AF. Current ESC guidelines state that consideration of rhythm control therapy as an early intervention step and as part of the ‘B’ element of the ABC pathway may be appropriate for patients with symptomatic AF for both quality of life and symptom improvement.25 Heart failure and AF frequently occur together.44 Rhythm control therapy26 and especially AF ablation27,45 have the potential to reduce outcomes in patients with AF and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy resulting from genetic and other disorders may present with a combination of AF and heart failure, and studies on these disorders are being conducted for an improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying the complex association between heart failure and AF, as well as between AF and sudden death.46–48 Implementation of a dynamic, interdisciplinary approach to AF management is expected to lead to further improved outcomes, but strategies to further improve adherence are needed.

One-third of the deaths recorded in XANTUS were due to non-cardiovascular causes. Our analyses identify anaemia and active cancer as features associated with death. The association of AF, newly detected AF, and cancer49,50 and the association of anaemia with death in patients with AF51–53 have recently been reported by others. Both associations warrant further mechanistic research. Reducing these deaths will require comprehensive assessment of patients with AF and treatment of their comorbidities as highlighted in AF guidelines as comprehensive care54,55 or, in an earlier iteration, integrated care of patients with AF.56 The findings in XANTUS call for validation. At face value, they suggest that attention should be paid to anaemia and to the detection of cancer as part of the comprehensive care of patients with AF. In addition, infections contributed to non-cardiovascular deaths in this cohort. Their timely detection and therapy can help to reduce this mortality. These should be considered in a holistic approach to patients with AF.57,58

Limitations

The limitations of the XANTUS programme have been described previously.10,11 Treatment with rivaroxaban was a requirement for inclusion. Selection bias could have resulted if patients considered their risk of stroke or bleeding when deciding whether to participate in the study, and physicians may have included patients with intact cognitive function preferentially. Patients included in XANTUS were also heterogeneous in terms of the time from their first diagnosis of AF. Nevertheless, the large study population, regional spread across five continents, central endpoint adjudication, and prospective design are important strengths of the study. The associations reported here cannot be used to infer causality. Not all therapies were captured during follow-up. Therefore, the influence of rhythm control and comorbidity treatment could not be reliably assessed in this data set.

Conclusions

The overall rate of stroke and death is low in anticoagulated patients with AF. The remaining deaths are predominantly cardiovascular and often due to heart failure and sudden death. These results not only underpin the effectiveness of current stroke prevention strategies but also highlight that the management of patients with AF needs to encompass other cardiovascular treatments to mitigate heart failure and sudden death. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying the association between the clinical features identified in this study and death and cardiovascular death, including further evaluation of rhythm control therapy and AF ablation.

Acknowledgements

The XANTUS steering committee thanks the patients who participated in the study, their caregivers and families, as well as the XANTUS investigators and their teams. The authors thank Lizahn Zwart for providing editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript, with funding from Bayer AG.

Contributor Information

Paulus Kirchhof, Department of Cardiology, University Heart and Vascular Center UKE Hamburg, Martinistraße 52, Gebäude Ost 70, 20246 Hamburg, Germany. German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK), partner site Hamburg/Kiel/Lübeck, Hamburg, Germany. Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK.

Sylvia Haas, Formerly Technical University Munich, Munich, Germany.

Pierre Amarenco, Department of Neurology and Stroke Centre, Paris-Diderot-Sorbonne University, Paris, France.

Alexander G G Turpie, Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada.

Miriam Bach, Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany.

Marc Lambelet, Chrestos Concept GmbH & Co KG, Essen, Germany.

Susanne Hess, Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany.

A John Camm, Cardiovascular and Cell Sciences Research Institute, St George’s University of London, London, UK.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from Bayer AG, Germany.

Conflict of interest: P.K. has received research support from the European Union, the British Heart Foundation (London, UK), the Leducq Foundation (Paris, France), the German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK, Berlin, Germany), and from several drug and device companies active in AF; he has also received honoraria from several such companies, including Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer/Bristol Myers Squibb. He is listed as an inventor on two pending patents held by the University of Birmingham. S.H. has served as a consultant for Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, and Sanofi. P.A. has served as a consultant for Bayer, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Edwards, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi. A.G.G.T. has been a consultant for Astellas, Bayer, Janssen Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC, Portola, and Takeda. M.B. and S.He. are employees of Bayer AG. M.L. is an employee of Chrestos Concept, which received funding for this analysis from Bayer AG. A.J.C. has received institutional research grants and personal fees as an advisor or speaker from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer/Bristol Myers Squibb.

Data availability

All authors had full access to all the data in the study and were involved in the drafting and reviewing of this manuscript. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the data analysis. The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Articles from Europace are provided here courtesy of Oxford University Press

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euae183

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://academic.oup.com/europace/article-pdf/26/7/euae183/58696167/euae183.pdf

Citations & impact

This article has not been cited yet.

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/164980968

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Real-world vs. randomized trial outcomes in similar populations of rivaroxaban-treated patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in ROCKET AF and XANTUS.

Europace, 21(3):421-427, 01 Mar 2019

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 30052894

Global Prospective Safety Analysis of Rivaroxaban.

J Am Coll Cardiol, 72(2):141-153, 01 Jul 2018

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 29976287

Cause of Death and Predictors of All-Cause Mortality in Anticoagulated Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation: Data From ROCKET AF.

J Am Heart Assoc, 5(3):e002197, 08 Mar 2016

Cited by: 82 articles | PMID: 26955859 | PMCID: PMC4943233

[Rivaroxaban at Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation: a Prospective Study and Clinical Practice].

Kardiologiia, 56(8):87-92, 01 Aug 2016

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 28290887

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.