Abstract

Background

Bipolar disorder often emerges from depressive episodes and is initially diagnosed as depression. This study aimed to explore the effects of a prior depression diagnosis on outcomes in patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder.Methods

This cohort study analyzed data of patients aged 18-64 years who received a new bipolar disorder diagnosis in Japan, using medical claims data from January 2005 to October 2020 provided by JMDC, Inc. The index month was defined as the time of the bipolar diagnosis. The study assessed the incidence of psychiatric hospitalization, all-cause hospitalization, and mortality, stratified by the presence of a preceding depression diagnosis and its duration (≥1 or <1 year). Hazard ratios (HRs) and p-values were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models, adjusted for potential confounders, and supported by log-rank tests.Results

Of the 5595 patients analyzed, 2460 had a history of depression, with 1049 experiencing it for over a year and 1411 for less than a year. HRs for psychiatric hospitalization, all hospitalizations, and death in patients with a history of depression versus those without were 0.92 (95% CI = 0.78-1.08, p = 0.30), 0.87 (95% CI = 0.78-0.98, p = 0.017), and 0.61 (95% CI = 0.33-1.12, p = 0.11), respectively. In patients with preceding depression ≥1 year versus <1 year, HRs were 0.89 (95% CI = 0.67-1.19, p = 0.43) for psychiatric hospitalization, 0.85 (95% CI = 0.71-1.00, p = 0.052) for all hospitalizations, and 0.25 (95% CI = 0.07-0.89, p = 0.03) for death.Conclusion

A prior history and duration of depression may not elevate psychiatric hospitalization risk after bipolar disorder diagnosis and might even correlate with reduced hospitalization and mortality rates.Free full text

Effect of prior depression diagnosis on bipolar disorder outcomes: A retrospective cohort study using a medical claims database

Abstract

Background

Bipolar disorder often emerges from depressive episodes and is initially diagnosed as depression. This study aimed to explore the effects of a prior depression diagnosis on outcomes in patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Methods

This cohort study analyzed data of patients aged 18–64 years who received a new bipolar disorder diagnosis in Japan, using medical claims data from January 2005 to October 2020 provided by JMDC, Inc. The index month was defined as the time of the bipolar diagnosis. The study assessed the incidence of psychiatric hospitalization, all‐cause hospitalization, and mortality, stratified by the presence of a preceding depression diagnosis and its duration (≥1 or <1

years who received a new bipolar disorder diagnosis in Japan, using medical claims data from January 2005 to October 2020 provided by JMDC, Inc. The index month was defined as the time of the bipolar diagnosis. The study assessed the incidence of psychiatric hospitalization, all‐cause hospitalization, and mortality, stratified by the presence of a preceding depression diagnosis and its duration (≥1 or <1 year). Hazard ratios (HRs) and p‐values were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models, adjusted for potential confounders, and supported by log‐rank tests.

year). Hazard ratios (HRs) and p‐values were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models, adjusted for potential confounders, and supported by log‐rank tests.

Results

Of the 5595 patients analyzed, 2460 had a history of depression, with 1049 experiencing it for over a year and 1411 for less than a year. HRs for psychiatric hospitalization, all hospitalizations, and death in patients with a history of depression versus those without were 0.92 (95% CI =

= 0.78–1.08, p

0.78–1.08, p =

= 0.30), 0.87 (95% CI

0.30), 0.87 (95% CI =

= 0.78–0.98, p

0.78–0.98, p =

= 0.017), and 0.61 (95% CI

0.017), and 0.61 (95% CI =

= 0.33–1.12, p

0.33–1.12, p =

= 0.11), respectively. In patients with preceding depression ≥1

0.11), respectively. In patients with preceding depression ≥1 year versus <1

year versus <1 year, HRs were 0.89 (95% CI

year, HRs were 0.89 (95% CI =

= 0.67–1.19, p

0.67–1.19, p =

= 0.43) for psychiatric hospitalization, 0.85 (95% CI

0.43) for psychiatric hospitalization, 0.85 (95% CI =

= 0.71–1.00, p

0.71–1.00, p =

= 0.052) for all hospitalizations, and 0.25 (95% CI

0.052) for all hospitalizations, and 0.25 (95% CI =

= 0.07–0.89, p

0.07–0.89, p =

= 0.03) for death.

0.03) for death.

Conclusion

A prior history and duration of depression may not elevate psychiatric hospitalization risk after bipolar disorder diagnosis and might even correlate with reduced hospitalization and mortality rates.

1. INTRODUCTION

Bipolar disorder is a multifaceted mental health condition characterized by episodes of mania and depression, affecting approximately 1%–2% of the global population over a lifetime.

1

,

2

The onset of bipolar disorder in a majority of cases is characterized by depressive episodes rather than mania or hypomania, with 58%–71% of bipolar I cases and over 90% of bipolar II cases initially presenting with depression.

3

,

4

Consequently, between 37% and 69% of those eventually diagnosed with bipolar disorder were initially diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD).

5

,

6

,

7

There is typically a delay of about 4 to 9 years from the first psychiatric consultation or provisional MDD diagnosis to a confirmed bipolar disorder diagnosis.

5

,

6

,

8

,

9

The rate at which diagnoses change from MDD to bipolar disorder varies significantly, ranging from 2% over 21

years from the first psychiatric consultation or provisional MDD diagnosis to a confirmed bipolar disorder diagnosis.

5

,

6

,

8

,

9

The rate at which diagnoses change from MDD to bipolar disorder varies significantly, ranging from 2% over 21 years to 20% within 3

years to 20% within 3 years.

10

,

11

,

12

Some studies indicate a consistent yearly transition rate of about 1.25%, while others report the highest rate of change, 3.9%, in the first year, which then decreases to 0.8% after 5

years.

10

,

11

,

12

Some studies indicate a consistent yearly transition rate of about 1.25%, while others report the highest rate of change, 3.9%, in the first year, which then decreases to 0.8% after 5 years.

2

,

12

,

13

Factors that increase the likelihood of transitioning from MDD to bipolar disorder include younger age at onset, psychotic features, atypical features, mixed features, a recurrent course, family history of bipolar disorder, and non‐response to antidepressants.

14

years.

2

,

12

,

13

Factors that increase the likelihood of transitioning from MDD to bipolar disorder include younger age at onset, psychotic features, atypical features, mixed features, a recurrent course, family history of bipolar disorder, and non‐response to antidepressants.

14

While psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are commonly utilized in the early stages of bipolar disorder, the debate over the most effective treatment strategy continues. 15 Notably, antidepressants are frequently prescribed in cases initially diagnosed with MDD before bipolar disorder is recognized, owing to their primary role in MDD treatment. 16 , 17 , 18 However, prevailing clinical guidelines for bipolar disorder generally advise against using antidepressants as the main treatment for bipolar depression. 19 , 20 , 21 This recommendation arises from concerns about their limited efficacy in bipolar disorder and the potential risk of inducing manic episodes or rapid cycling. 22 , 23 , 24 Despite these concerns, the effect of prior antidepressant use on the clinical outcomes after a bipolar diagnosis remains under‐explored. To effectively assess the risks and benefits of treating pre‐existing MDD in the context of subsequent bipolar disorder outcomes, more definitive research is required.

Medical record databases, comprising extensive archives of healthcare interactions including diagnoses and prescriptions, serve as invaluable resources for clinical research. These databases encapsulate real‐world outcomes, including hospitalization and mortality, covering large and diverse patient cohorts across various healthcare settings. A significant advantage of these databases lies in their ability to facilitate longitudinal tracking of patients, encompassing periods both before and after changes in diagnoses if any.

The objective of the current study was to investigate the impact of diagnosis of pre‐existing depression on the clinical outcomes of patients who are subsequently diagnosed with bipolar disorder. To accomplish this, we utilized a comprehensive medical record database, reflecting real‐world scenarios.

2. METHOD

2.1. Study design and setting

This cohort study undertook a comprehensive examination of patients newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder in Japan. It tracked patients from the month of diagnosis, retrospectively reviewing prior depression diagnoses and subsequent event occurrences. Claims records and health examination data were sourced from JMDC, Inc., covering the period from January 1, 2005, to October 30, 2020. The JMDC Claims Database is an epidemiological medical claims database that has accumulated claims data (inpatient, outpatient, dispensing) and medical examination data for employees and their families received from multiple employer‐based health insurance associations since 2005. This database currently includes data on approximately 17 million individuals. It uniquely allows for continuous tracking of patient data across multiple healthcare facilities, notwithstanding changes in hospital or the use of multiple institutions, unless there is a cessation of insurance coverage due to employment termination, retirement, death, or other reasons. The present study was conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines. 25 This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University (approval number: R3098; date: August 31, 2021), which waived the requirement for an informed consent due to the anonymous nature of the data.

2.2. Patient

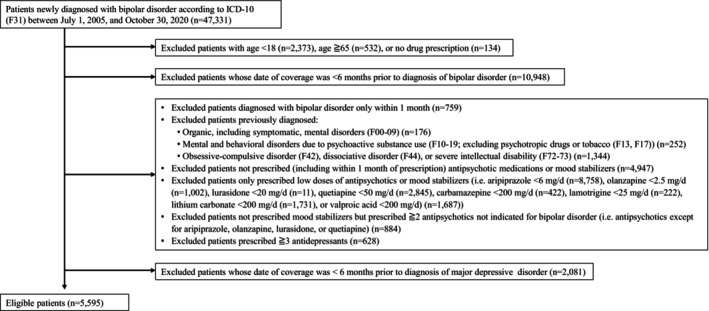

To accurately select patients with bipolar disorder for the study, three clinical psychiatrists (HS, TT, and KW) conducted a thorough review of 100 randomly chosen cases diagnosed with bipolar disorder from the JMDC claims dataset. The review focused on patient characteristics such as gender, age, insured status, visit category (outpatient or inpatient) at the time of diagnosis, the diagnostic trajectory of mental illness (ICD‐10: F00‐99), and the dosages of psychotropic medications prescribed both in the year before and after the diagnosis. These medications included antipsychotics (ATC codes: N05A), anxiolytics (N05B), hypnotics (N05C), antidepressants (N06A), lithium (N05AN), carbamazepine (N03AF01), valproic acid (N03AG01), and lamotrigine (N03AX09). This thorough examination led to the establishment of specific selection criteria for the study population: (1) patients newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD‐10, F31) between July 1, 2005, and October 30, 2020, (2) patients aged between 18 and 64 years at the time of diagnosis, and (3) patients with data available for six or more months prior to their bipolar disorder diagnosis, to confirm the initial diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The study divided these individuals into two cohorts: one with a prior MDD (F32) diagnosis according to the ICD‐10 and one without. For those with an MDD history, only patients with data spanning at least 6

years at the time of diagnosis, and (3) patients with data available for six or more months prior to their bipolar disorder diagnosis, to confirm the initial diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The study divided these individuals into two cohorts: one with a prior MDD (F32) diagnosis according to the ICD‐10 and one without. For those with an MDD history, only patients with data spanning at least 6 months before their MDD diagnosis were included for further analysis, ensuring the diagnosis was a new occurrence. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder only within 1

months before their MDD diagnosis were included for further analysis, ensuring the diagnosis was a new occurrence. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder only within 1 month, (2) patients previously diagnosed with organic mental disorders (F00‐09), substance‐related disorders (F10‐19) (excluding psychotropic drugs or tobacco (F13 or F17)), obsessive‐compulsive disorder (F42), dissociative disorder (F44), or severe intellectual disability (F72‐73), (3) patients not prescribed (including prescriptions within 1

month, (2) patients previously diagnosed with organic mental disorders (F00‐09), substance‐related disorders (F10‐19) (excluding psychotropic drugs or tobacco (F13 or F17)), obsessive‐compulsive disorder (F42), dissociative disorder (F44), or severe intellectual disability (F72‐73), (3) patients not prescribed (including prescriptions within 1 month), or only prescribed low doses of, antipsychotics or mood stabilizers (i.e. aripiprazole <6

month), or only prescribed low doses of, antipsychotics or mood stabilizers (i.e. aripiprazole <6 mg/d, olanzapine <2.5

mg/d, olanzapine <2.5 mg/d, lurasidone <20

mg/d, lurasidone <20 mg/d, quetiapine <50

mg/d, quetiapine <50 mg/d, carbamazepine <200

mg/d, carbamazepine <200 mg/d, lamotrigine <25

mg/d, lamotrigine <25 mg/d, lithium carbonate <200

mg/d, lithium carbonate <200 mg/d, or valproic acid <200

mg/d, or valproic acid <200 mg/d), (4) patients not prescribed mood stabilizers but prescribed two or more antipsychotics not indicated for bipolar disorder (i.e. antipsychotics except for aripiprazole, olanzapine, lurasidone, or quetiapine), or (5) patients prescribed three or more antidepressants following their bipolar disorder diagnosis. Notably, criterion (4) was established to exclude patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. It was specified that cases involving the use of two or more antipsychotics not indicated for bipolar disorder, and lacking concurrent mood stabilizer therapy, were considered indicative of schizophrenia rather than bipolar disorder. Criterion (5) was designed to exclude patients with MDD. Cases in which patients were prescribed three or more antidepressants concurrently were presumed to primarily have MDD as the underlying condition.

mg/d), (4) patients not prescribed mood stabilizers but prescribed two or more antipsychotics not indicated for bipolar disorder (i.e. antipsychotics except for aripiprazole, olanzapine, lurasidone, or quetiapine), or (5) patients prescribed three or more antidepressants following their bipolar disorder diagnosis. Notably, criterion (4) was established to exclude patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. It was specified that cases involving the use of two or more antipsychotics not indicated for bipolar disorder, and lacking concurrent mood stabilizer therapy, were considered indicative of schizophrenia rather than bipolar disorder. Criterion (5) was designed to exclude patients with MDD. Cases in which patients were prescribed three or more antidepressants concurrently were presumed to primarily have MDD as the underlying condition.

2.3. Assessment measures

The present retrospective analysis tracked key clinical outcomes from the time of bipolar disorder diagnosis up to October 30, 2020. The primary outcomes of interest were psychiatric hospitalization, hospitalization for any reason, and mortality. Patients received treatment and care following standard clinical practices.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Patients were stratified into groups based on their history of MDD diagnosis prior to the bipolar disorder diagnosis. The psychiatric hospitalization rate, overall hospitalization rate, and crude mortality rate were calculated for each group. The incidence rates for these outcomes were then compared between those with and without a preceding diagnosis of MDD. To adjust for potential confounders, hazard ratios and p‐values were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models, supplemented by log‐rank tests. Adjustments were made for several variables, including gender, age, insured person status (i.e. an insured individual or a dependent), comorbidity levels as measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (i.e. CCI scores of ≥1 or 0), year of bipolar disorder diagnosis (i.e. 2012 or earlier, or 2013 or later), and prior history of overall hospitalization. The CCI was utilized to quantify the burden of comorbidities that might influence mortality risk, with a higher score indicating a greater risk. Similarly, for patients with a history of MDD diagnosis, analyses were conducted separately for those with a duration of preceding MDD diagnosis ≥1 and <1 year. The same statistical approaches were applied to compare incidence rates of psychiatric hospitalization, overall hospitalization, and mortality across these subgroups. Statistical significance was set at a p‐value of <0.05 (two‐tailed). All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

year. The same statistical approaches were applied to compare incidence rates of psychiatric hospitalization, overall hospitalization, and mortality across these subgroups. Statistical significance was set at a p‐value of <0.05 (two‐tailed). All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient characteristics

A total of 5595 patients were included in the present analysis (Figure 1). Among them, 2460 (44.0%) had a preceding diagnosis of MDD. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. In the group with a preceding diagnosis of MDD, the mean duration between the diagnoses of MDD and subsequent bipolar disorder was 18.2 ±

± 23.6

23.6 months. Among the 2460 patients with a preceding diagnosis of MDD, 1049 had experienced MDD diagnosis for ≥1

months. Among the 2460 patients with a preceding diagnosis of MDD, 1049 had experienced MDD diagnosis for ≥1 year, while 1411 had a history of MDD diagnosis lasting <1

year, while 1411 had a history of MDD diagnosis lasting <1 year.

year.

TABLE 1

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

| Characteristics | Preceding MDD diagnosis (n = = 2460) 2460) | No preceding MDD diagnosis (n = = 3135) 3135) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 37.3 (11.3) | 36.0 (11.8) |

| Male, n (%) | 1420 (57.7) | 1607 (51.3) |

| Insured individual, n (%) | 1718 (69.8) | 1938 (61.8) |

| Physical comorbidity (CCI ≥1), n (%) | 203 (8.3) | 283 (9.0) |

| History of psychiatric admission, n (%) | 238 (9.7) | 205 (6.5) |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; MDD, major depressive disorder; SD, standard deviation.

3.2. Effect of preceding MDD diagnosis on clinical outcome

The crude rate of psychiatric hospitalization was 8.0% (196/2460) in the group with a preceding diagnosis of MDD and 7.6% (239/3135) in the group without a preceding diagnosis of MDD. No significance was observed in the incidence rates of psychiatric hospitalization between the two groups (2.63/1000 person‐months vs. 2.56/1000 person‐months, adjusted hazard ratio (HR): 0.92, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.78–1.08, p‐value: 0.30).

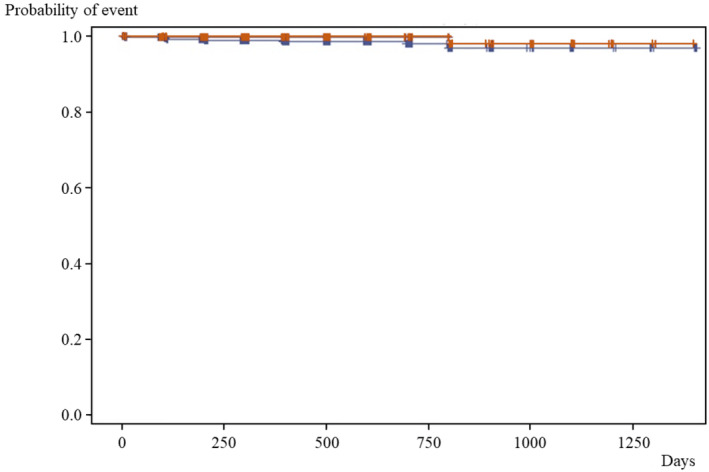

The crude rate of overall hospitalization was 23.2% (571/2460) in the group with a preceding diagnosis of MDD and 23.8% (746/3135) in the group without a preceding diagnosis of MDD. There was a statistical significance in the incidence rates of overall hospitalization between the two groups (9.07/1000 person‐months vs. 9.39/1000 person‐months, adjusted HR: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.78–0.98, p‐value: 0.02, Figure 2).

Time to hospitalization for any reason based on a preceding diagnosis of MDD. The red line represents individuals with a prior diagnosis of MDD, while the blue line denotes those without a preceding diagnosis of MDD. MDD, major depressive disorder.

The crude mortality rate was 0.69% (17/2460) in the group with a preceding diagnosis of MDD and 0.96% (30/3135) in the group without a preceding diagnosis of MDD. The mortality incidence rates were 2.70/100000 person‐months and 3.81/100000 person‐months, respectively. No significant difference was found in the mortality incidence rates between the two groups (adjusted HR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.33–1.12, p‐value: 0.11).

3.3. Effect of duration of preceding MDD diagnosis on clinical outcome

The crude rate of psychiatric hospitalization was 8.6% (90/1049) in the group with preceding MDD diagnosis ≥1 year and 7.5% (106/1411) in the group with preceding MDD diagnosis <1

year and 7.5% (106/1411) in the group with preceding MDD diagnosis <1 year. There was no significant difference in the incidence rates of psychiatric hospitalization between the two groups (2.93/1000 person‐months vs. 2.42/1000 person‐months, adjusted HR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.67–1.19, p‐value: 0.43).

year. There was no significant difference in the incidence rates of psychiatric hospitalization between the two groups (2.93/1000 person‐months vs. 2.42/1000 person‐months, adjusted HR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.67–1.19, p‐value: 0.43).

The crude rate of overall hospitalization was 23.2% (243/1049) in the group with preceding MDD diagnosis ≥1 year and 23.2% (328/1411) in the group with preceding MDD diagnosis <1

year and 23.2% (328/1411) in the group with preceding MDD diagnosis <1 year. There was no significance in the incidence rates of overall hospitalization between the two groups (9.25/1000 person‐months vs. 8.94/1000 person‐months, adjusted HR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.71–1.00, p‐value: 0.052).

year. There was no significance in the incidence rates of overall hospitalization between the two groups (9.25/1000 person‐months vs. 8.94/1000 person‐months, adjusted HR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.71–1.00, p‐value: 0.052).

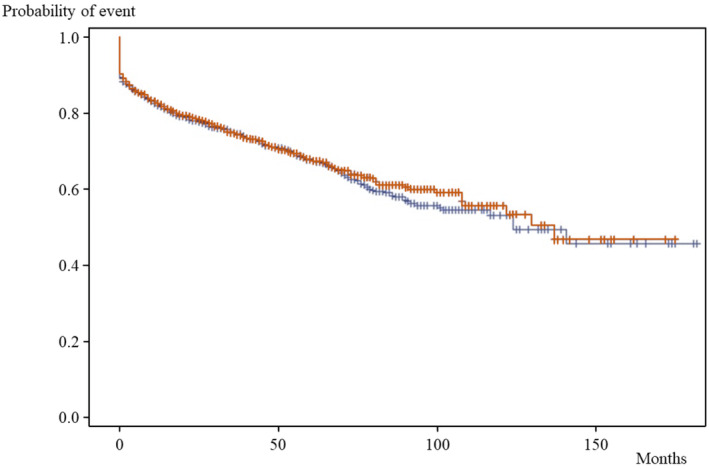

The crude mortality rate was 0.29% (3/1049) in the group with preceding MDD diagnosis ≥1 year and 0.99% (14/1411) in the group with preceding MDD diagnosis <1

year and 0.99% (14/1411) in the group with preceding MDD diagnosis <1 year. The mortality incidence rates were 1.16/100000 person‐months and 3.77/100000 person‐months, respectively. There was a significant difference in the mortality incidence rates between the two groups (adjusted HR: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.07–0.89, p‐value: 0.03, Figure 3).

year. The mortality incidence rates were 1.16/100000 person‐months and 3.77/100000 person‐months, respectively. There was a significant difference in the mortality incidence rates between the two groups (adjusted HR: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.07–0.89, p‐value: 0.03, Figure 3).

4. DISCUSSION

This study was the first to examine the impact of a prior MDD diagnosis and its duration on outcomes following a bipolar disorder diagnosis. The analysis indicated that neither a history of MDD diagnosis nor the length of diagnosed duration significantly predicted the changes in rates of psychiatric hospitalization post‐diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Intriguingly, a history of MDD diagnosis was associated with reduced hospitalization rates for all causes, and a diagnosis of MDD for more than a year showed decreased mortality rates. Given that these patients were treated and cared for according to standard clinical practices, it appears that a prior diagnosis and treatment for MDD may not lead to more severe psychiatric states following a bipolar disorder diagnosis. Instead, they may be linked to a reduction in adverse physical health outcomes.

The present study established that neither a prior diagnosis of MDD nor its duration significantly impacted psychiatric hospitalization rates following a bipolar disorder diagnosis. When MDD is diagnosed, treatment is generally conducted as per standard practice guidelines, including the use of antidepressant medications.

16

,

17

,

18

This indicates that antidepressant therapy prior to the emergence of bipolar disorder may be acceptable without worsening the mental conditions in subsequent bipolar disorder. Existing literature has not addressed the impact of antidepressants prescribed prior to a bipolar disorder diagnosis, while studies focusing on their effects post‐diagnosis reveal mixed results regarding psychiatric hospitalization rates. For instance, a database study of 190 824 patients with bipolar or schizoaffective disorder over 3

824 patients with bipolar or schizoaffective disorder over 3 months on average reported that valproic acid, aripiprazole, and bupropion were associated with lower hospitalization rates than lithium carbonate, while most antidepressants were correlated with higher rates.

26

On the other hand, one cohort study of 519 hospitalized bipolar patients over a year showed that no form of pharmacotherapy, including antidepressants, significantly affected rehospitalization rates.

27

A pertinent factor influencing the present results may be the relatively brief average interval of 1.5

months on average reported that valproic acid, aripiprazole, and bupropion were associated with lower hospitalization rates than lithium carbonate, while most antidepressants were correlated with higher rates.

26

On the other hand, one cohort study of 519 hospitalized bipolar patients over a year showed that no form of pharmacotherapy, including antidepressants, significantly affected rehospitalization rates.

27

A pertinent factor influencing the present results may be the relatively brief average interval of 1.5 years between MDD and bipolar disorder diagnoses in this study, contrasting with the 4–9‐year span reported in previous research.

5

,

6

,

8

,

9

Recent advancements in psychiatric care may enable earlier diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Under these circumstances, treating depression prior to its diagnosis may not markedly impact the long‐term prognosis of the condition. Additionally, it is essential to differentiate between bipolar disorder and unipolar depression when treating a depressed patient. This can be achieved by inquiring about any history of manic episodes. Even in patients with depressive episodes who do not have an apparent history of mania, it is important to carefully evaluate specific symptoms, the course of the illness, and other characteristics that might indicate a risk of transitioning to bipolar disorder in the future.

14

years between MDD and bipolar disorder diagnoses in this study, contrasting with the 4–9‐year span reported in previous research.

5

,

6

,

8

,

9

Recent advancements in psychiatric care may enable earlier diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Under these circumstances, treating depression prior to its diagnosis may not markedly impact the long‐term prognosis of the condition. Additionally, it is essential to differentiate between bipolar disorder and unipolar depression when treating a depressed patient. This can be achieved by inquiring about any history of manic episodes. Even in patients with depressive episodes who do not have an apparent history of mania, it is important to carefully evaluate specific symptoms, the course of the illness, and other characteristics that might indicate a risk of transitioning to bipolar disorder in the future.

14

Patients with a history of MDD diagnosis experienced lower hospitalization rates for all causes compared to those without such a history. In an analysis of general hospital admissions over 2 years for 18

years for 18 380 patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorder, common reasons for admission were diseases of the urinary tract, gastrointestinal system, oncology, and respiratory system.

28

Their hospitalization rates, particularly for conditions such as poisoning, injuries, endocrine/metabolic, hematologic, neurologic, dermatologic, and infectious diseases, were notably higher compared to the general population.

28

These health complications can often be linked to factors such as psychiatric symptom‐related self‐neglect, limited access to medical care, and self‐harm. A pre‐existing diagnosis of MDD, followed by appropriate treatment and care, may improve psychiatric symptoms and enhance access to medical care, potentially reducing the incidence of hospitalizations for physical health issues.

380 patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorder, common reasons for admission were diseases of the urinary tract, gastrointestinal system, oncology, and respiratory system.

28

Their hospitalization rates, particularly for conditions such as poisoning, injuries, endocrine/metabolic, hematologic, neurologic, dermatologic, and infectious diseases, were notably higher compared to the general population.

28

These health complications can often be linked to factors such as psychiatric symptom‐related self‐neglect, limited access to medical care, and self‐harm. A pre‐existing diagnosis of MDD, followed by appropriate treatment and care, may improve psychiatric symptoms and enhance access to medical care, potentially reducing the incidence of hospitalizations for physical health issues.

Individuals diagnosed with MDD for over a year exhibited lower mortality rates compared to those with a shorter MDD history in the present study, suggesting that shorter intervals between depressive and manic phases might be linked to increased mortality. Notably, rapid‐cycling bipolar disorder, characterized by frequent and brief phase changes, is associated with higher rates of obesity, hyperglycemia, metabolic syndrome, and substance use disorders as well as elevated suicide attempts. 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 The suicide rate in bipolar disorder is approximately 0.1–0.4 per 100 person‐years, with suicide accounting for an estimated 15%–20% of deaths. 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 Furthermore, suicide attempts are more frequent in cases where depressive episodes predominate, normally beginning with a depressive phase, compared to those primarily experiencing manic episodes. 40 These findings underscore the importance of heightened vigilance for mortality risks, including suicide, particularly in the early stages following a change in mood episodes. 41

This study has several limitations. Firstly, being an analysis of medical record datasets, the classification of study patients relied on disease names from claims records rather than specific operational diagnostic criteria. This methodology could lead to potential discrepancies in clinical judgments. Moreover, the study did not take into account various factors that could influence the findings, such as the severity of the patients' conditions (e.g. bipolar disorder type I or II) and a range of biological and clinical characteristics, including aspects of bipolarity. Secondly, the detection of prior MDD diagnosis is contingent upon medical examination. Consequently, there is a possibility that cases with a history of MDD diagnosis may have been inaccurately classified as having no prior MDD diagnosis. Thirdly, the specific nature of MDD treatments post‐diagnosis, particularly antidepressant use, was not examined. Finally, the study was limited to outcomes that could be identified through medical claims data, focusing only on significant adverse outcomes like hospitalization or death.

In conclusion, the present study indicates that a history and duration of prior MDD diagnosis do not increase the risk of psychiatric hospitalization after a bipolar disorder diagnosis. On the contrary, they may be linked to lower rates of hospitalization for any reason and decreased mortality rates. Despite the limitations of analyzing receipt and health examination data, our findings suggest that relatively early diagnosis of MDD is associated with a lower risk of these events in bipolar disorder. To corroborate these findings, future research in the form of prospective cohort studies with the accurate assessment of patients' medical histories and psychiatric symptoms is necessary.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

HS received grants from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Japan Research Foundation Clinical Pharmacology, and Takeda Science Foundation, and honorarium from Eisai, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Shionogi Pharma, Yoshitomiyakuhin, Sumitomo Pharma, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, MSD, and Lundbeck Japan. HS is an Editorial Board member of Neuropsychopharmacology Reports and a first/corresponding author of this article. To minimize bias, they were excluded from all editorial decision‐making related to the acceptance of this article for publication. MN has nothing to declare. TT received a grant from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and honorarium from Takeda Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Shionogi Pharma, Yoshitomiyakuhin, Sumitomo Pharma, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, MSD, Nippon Boehringer lngelheim, Mylan EPD, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Viatris, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Janssen Pharmaceutical, TEIJIN PHARMA, and Lundbeck Japan. KB and TN are full‐time employees of Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. KW has received manuscript fees or speaker's honoraria from Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck Japan, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Sumitomo Pharma, and Takeda Pharmaceutical and received research/grant support from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Otsu‐ka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Sumitomo Pharma, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. In addition, KW is a consultant of Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck Japan, Luye Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. KK has received consulting fees from Advanced Medical Care Inc., JMDC Inc., and Shin Nippon Biomedical Laboratories Ltd.; executive compensation from Cancer Intelligence Care Systems, Inc.; honoraria from Shionogi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Taisho Pharmaceutical, and Pharma Business Academy; and grants from Eisai Co., Ltd., Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., OMRON Corporation, and Toppan Inc.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of The Research Protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University (approval number: R3098; date: August 31st, 2021), which waived the requirement for an informed consent due to the anonymous nature of the data.

Informed Consent: N/A.

Registry and the Registration No. of the Study/Trial: N/A.

Animal Studies: N/A.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM OTHER SOURCES

We own all the rights in the material submitted and agree to transfer, assign, or otherwise convey all copyright ownership to the Neuropsychopharmacology Reports upon acceptance of this manuscript.

Notes

Sakurai H, Nakashima M, Tsuboi T, Baba K, Nosaka T, Watanabe K, et al. Effect of prior depression diagnosis on bipolar disorder outcomes: A retrospective cohort study using a medical claims database. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2024;44:591–598. 10.1002/npr2.12457 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from JMDC, Inc., but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of JMDC, Inc.

REFERENCES

Articles from Neuropsychopharmacology Reports are provided here courtesy of Wiley

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/165250213

Article citations

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of suspected difficult-to-treat depression.

Front Psychiatry, 15:1371242, 21 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39234616 | PMCID: PMC11371740

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Hospitalization risk in pediatric patients with bipolar disorder treated with lurasidone vs. other oral atypical antipsychotics: a real-world retrospective claims database study.

J Med Econ, 24(1):1212-1220, 01 Jan 2021

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 34647502

Hospitalization Risk for Adults with Bipolar I Disorder Treated with Oral Atypical Antipsychotics as Adjunctive Therapy with Mood Stabilizers: A Retrospective Analysis of Medicaid Claims Data.

Curr Ther Res Clin Exp, 94:100629, 27 Mar 2021

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 34306269 | PMCID: PMC8296072

Prevalence and humanistic impact of potential misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder among patients with major depressive disorder in a commercially insured population.

J Manag Care Pharm, 14(7):631-642, 01 Sep 2008

Cited by: 19 articles | PMID: 18774873

[Bipolar I disorder in France: prevalence of manic episodes and hospitalisation-related costs].

Encephale, 29(3 pt 1):248-253, 01 May 2003

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 12876549

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

1

1