Abstract

Introduction

Post-acne scars are a prevalent cosmetic complaint that usually require multi-modality treatment to achieve accepted results.Objectives

The target of this research was to evaluate and compare the efficacy and safety of microneedling with topical insulin versus microneedling with non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid in atrophic post-acne scar treatment.Methods

The current comparative split-face research included 30 patients with atrophic facial acne scars. Each patient received six sessions of microneedling with topical insulin on one side of the face and microneedling with non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid on the other side. Sessions were done three weeks apart, and digital photographs were taken before and three months after the last treatment session. Goodman and Baron qualitative and quantitative grading system was used to evaluate the improvement across both sides of the face, along with patient satisfaction.Results

Three months after the last session, a statistically significant improvement in qualitative acne scar grading on both sides of the face (P < 0.001) was reported, with non-significant difference between the two sides (P = 0.864). Moreover, the mean percentage of improvement in quantitative acne scar grading was 49.18 ± 13.22 on the insulin side and 47.72 ± 15.08 on the hyaluronic acid side, with non-significant difference between the two sides after treatment (P = 0.235).Conclusion

Both microneedling with topical insulin and with non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid achieved comparable significant improvement of atrophic post-acne scars.Free full text

Microneedling with Topical Insulin Versus Microneedling with Non-Cross-Linked Hyaluronic Acid for Atrophic Post-Acne Scars: A Split-Face Study

Abstract

Introduction

Post-acne scars are a prevalent cosmetic complaint that usually require multi-modality treatment to achieve accepted results.

Objectives

The target of this research was to evaluate and compare the efficacy and safety of microneedling with topical insulin versus microneedling with non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid in atrophic post-acne scar treatment.

Methods

The current comparative split-face research included 30 patients with atrophic facial acne scars. Each patient received six sessions of microneedling with topical insulin on one side of the face and microneedling with non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid on the other side. Sessions were done three weeks apart, and digital photographs were taken before and three months after the last treatment session. Goodman and Baron qualitative and quantitative grading system was used to evaluate the improvement across both sides of the face, along with patient satisfaction.

Results

Three months after the last session, a statistically significant improvement in qualitative acne scar grading on both sides of the face (P < 0.001) was reported, with non-significant difference between the two sides (P = 0.864). Moreover, the mean percentage of improvement in quantitative acne scar grading was 49.18 ± 13.22 on the insulin side and 47.72 ± 15.08 on the hyaluronic acid side, with non-significant difference between the two sides after treatment (P = 0.235).

Conclusion

Both microneedling with topical insulin and with non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid achieved comparable significant improvement of atrophic post-acne scars.

Introduction

Acne scarring is a common cosmetic problem. Normal tissue replacement with fibrous scars occurs due to acne’s inflammatory process [1]. Despite the presence of various treatment options for acne scars, a standard treatment that will permanently improve the condition has not been established, and combined methods should be used to obtain ideal cosmetic results [2].

Microneedling is a well-established option for scar management, especially when combined with topical agents. It is a transdermal collagen induction and trans-epidermal medication delivery technique in which very tiny needles are rolled into the skin to penetrate it superficially and controllably [3].

Blood glucose concentration is balanced by insulin. Because of insulin’s roles in metabolism, cellular proliferation, protein synthesis, and growth, it is considered a potent factor in the healing process. Insulin also controls the proliferation, growth, migration, and development of fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and endothelial cells [4].

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a mucopolysaccharide found in high concentration in the epidermis and dermis in order to maintain skin hydration. Non-cross-linked HA can promote collagen deposition via enhancing the anabolic activity of dermal fibroblasts, and it plays a critical role in the wound healing process [5].

Objective

A few studies have evaluated the efficacy of topical insulin for acne scar treatment. Thus, the target of this research was to evaluate microneedling with topical insulin versus with non-cross-linked HA in atrophic acne scar treatment.

Methods

The current prospective split-face comparative research enrolled 30 cases diagnosed clinically with atrophic acne scars who were randomly selected from the Al-Zahraa Hospital Dermatology Outpatient Clinic. The study was approved by The Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the Faculty of Medicine for Girls, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt, with approval code 202104792.

Before enrollment in this research study, the procedure details were discussed with the patients, and informed written consent was obtained from them. The presence of atrophic facial acne scars, age between 18 and 45 years, and the absence of post-acne scar treatment in the previous three months were required for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, lactation, keloidal tendency, coagulation disorders or bleeding tendency, active inflammatory acne lesions, active infection such as viral warts or herpes simplex in the treatment area, and uncontrolled blood glucose level.

Treatment Protocol

A sufficient layer of topical anesthetic cream (pridocaine cream, formed of prilocaine 2.5% + lidocaine 2.5%) was applied to the face 30 minutes before the procedure, then the face was washed with water and disinfected with alcohol. The whole face was treated with microneedling using a dermapen (Dr. Pen Ultima A6; Bjheyetec Electronic Technology Co., Guangzhou, China) with 36 disposable needles at 1.5 mm depth and adjusted speed. The dermapen device was applied over the skin with one hand while the other hand stretched the skin to expose the scar’s base for the dermapen. The device was moved vertically until uniform pinpoint bleeding was seen. To avoid encrustation, sterile saline was used to wipe the blood away.

After the needling process, 1–2 ml of topical insulin (Human Actrapid 100 IU/ml solution; Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bagsvμrd, Denmark) was applied to one side of the face and 1–2 ml of topical non-cross-linked HA solution (Presensa fullnesse 3.5% Persensa Spain) was applied to the other side. Side selection for either insulin or HA was done randomly by sealed envelope method.

After the procedure, the patients were advised to use photo-protective measures and apply topical fusidic acid cream twice a day for 3–5 days. Acyclovir 400 mg /8 hours was prescribed for one week (especially to patients with a history of recurrent herpes labialis). Blood glucose level was measured before and after the procedure for all the patients. This treatment protocol was repeated every three weeks for a total of six sessions,

Assessment of the Responses

Evaluation was done at baseline, monthly after the last session, and the final evaluation three months after the last treatment session by Goodman and Baron qualitative and quantitative acne scarring grading systems [6,7].

Patient Satisfaction

The patients were asked to rate their improvement in acne scars on both sides of the face in comparison to pre-treatment condition using the quartile scale [210].

Grade 0: Slight improvement < 25%

Grade 1: Moderate improvement 25%–49%

Grade 2: Considerable improvement 50%–74%

Grade 3: Marked improvement ≥ 75%

Side Effects

Erythema, edema, post-inflammatory hypo or hyperpigmentation, hypoglycemia, and pain were discussed verbally with the cases and evaluated by the doctor throughout the study.

The patients were asked to rate their pain according to a numeric rating scale (NRS) ranging from 0–10 [11].

Statistical Analysis

Data collection, editing, coding, and entry were all accomplished with IBM SPSS version 23. When the variables were parametric or non-parametric, the quantitative data are presented as means, ranges, and standard deviations with inter-quartile ranges (IQR). The error margin was established at 5% based on a 95% confidence interval This indicates that a P value of 0.05 was used for statistical significance.

Results

The present research included 21 females (70%) and 9 males (30%), with a mean age of 30.63 ± 4.72 years. Eight cases were of skin phototype III (26.7%), and 22 cases were of type IV (73.3%). The duration of post-acne scars ranged from two to 18 years with a median (IQR) of 5.25 (4–12) years (Table 1).

Table 1

Demographic Data of the Studied Patients.

| No. = 30 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean±SD | 30.63 ± 4.72 |

| Range | 23 – 38 | |

| Sex | Female | 21 (70.0%) |

| Male | 9 (30.0%) | |

| Skin phototype | III | 8 (26.7%) |

| IV | 22 (73.3%) | |

| Scar duration (Years) | Median (IQR) | 5.25 (4 – 12) |

| 2 – 18 | ||

IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

Clinical Assessment

Before treatment, a non-significant difference was noticed between both sides of the face regarding both qualitative and quantitative Goodman and Baron scoring system; after treatment, the qualitative grading of acne scars was significantly improved on insulin side and HA side (P < 0.001), with a non-significant difference between both sides (P = 0.864). Also, the quantitative Goodman and baron scoring system was lower after treatment on the insulin side, from 15.80 ± 3.91 to 7.87 ± 2.30, with a 49.18% improvement; on the HA side, it decreased from 14.07 ± 2.83 to 7.30 ± 2.34, with a 47.72% improvement. This improvement is considered significant on both sides of the face (P < 0.001), with a non-significant difference between both sides after treatment (P = 0.348) (Tables 2 and and33).

Table 2

Comparison between the Insulin- and HA-Treated Sides, Qualitative Grading Before and After Treatment.

| Qualitative | Insulin side | HA side | Test value* | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||||

| Before | II: mild | 1 | 3.3% | 1 | 3.3% | 1.137 | 0.566 |

| III: moderate | 15 | 50.0% | 19 | 63.3% | |||

| IV: sever | 14 | 46.7% | 10 | 33.3% | |||

| After | I: macular | 1 | 3.3% | 1 | 3.3% | 0.293 | 0.864 |

| II: mild | 17 | 56.7% | 19 | 63.3% | |||

| III: moderate | 12 | 40.0% | 10 | 33.3% | |||

| IV: sever | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |||

| Chi-square test | 29.556 | 29.993 | |||||

| P-value | <0.001 (HS) | <0.001 (HS) | |||||

P > 0.05: Nonsignificant (NS); P < 0.05: Significant (S); P < 0.01: highly significant (HS).

HA = hyaluronic acid.

Table 3

Comparison between the Insulin- and HA-treated Sides, Quantitative Grading Before and After Treatment and Percentage of Improvement.

| Quantitative | Insulin side | HA side | Test value | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. = 30 | No. = 30 | ||||

| Before | Mean ± SD | 15.80 ± 3.91 | 14.07 ± 2.83 | 1.968• | 0.054 |

| Range | 9 – 24 | 8 – 19 | |||

| After | Mean ± SD | 7.87 ± 2.30 | 7.30 ± 2.34 | 0.947• | 0.348 |

| Range | 3 – 12 | 2 – 12 | |||

| Percentage of improvement | Mean ± SD | 49.18 ± 13.22 | 47.72 ± 15.08 | 0.400• | 0.691 |

| Range | 21.43 – 80 | 20 – 83.33 | |||

| Paired t-test | −13.840 | −13.664 | |||

| P | <0.001 (HS) | <0.001 (HS) | |||

P > 0.05: Nonsignificant (NS); P < 0.05: Significant (S); P < 0.01: highly significant (HS)

HA = hyaluronic acid.

On comparing the degree of reduction in quantitative grading after treatment, a non-significant difference was noticed between both sides of the face (P = 0.235).

On the insulin side, moderate improvement was achieved in 12 cases (40%), good improvement in eight cases (26.7%), minimal improvement in eight cases (26.7%), and very good improvement in two cases (6.7%). On the HA side, moderate improvement was achieved in 17 cases (56.7%), good improvement in four cases (13.3%), minimal improvement in nine cases (30%); no case had very good improvement (0.0%) (Table 4).

Table 4

Comparison between the Insulin- and HA-treated Sides, Reduction Degree in Quantitative Grading.

| Quantitative | Insulin Side | HA Side | Test value | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. = 30 | No. = 30 | ||||

| Reduction | Minimal | 8 (26.7%) | 9 (30.0%) | 4.254 | 0.235 |

| Moderate | 12 (40.0%) | 17 (56.7%) | |||

| Good | 8 (26.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | |||

| Very good | 2 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

P > 0.05: Nonsignificant (NS); P < 0.05: Significant (S); P < 0.01: highly significant (HS)

HA = hyaluronic acid.

Quantitative Grading After Treatment for Each Scar Type

Boxcar scars showed significant improvement after treatment, with improvement percentages of 54.87% and 54.80% on the insulin side and HA side, respectively. Rolling scars also showed significant improvement after treatment, with improvement percentages of 60.63% and 50.26% on the insulin and HA side, respectively. Ice pick scars had the least percentage of improvement, 37.06% and 34.44% on the insulin and HA sides, respectively. On comparing the quantitative scoring after treatment in terms of improvement according to scar type, a non-significant difference was noticed between both sides of the face (Table 5).

Table 5

Comparison between the Insulin- and HA-treated Sides Quantitative Grading Before and After Treatment in Each Scar Type.

| Quantitative | Before | After | Percentage of Improvement | Test value• | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Box scar | Insulin side | Mean ± SD | 17.00 ± 3.65 | 7.71 ± 2.06 | 54.87 ± 5.20 | −12.433 | 0.000 |

| Range | 11 – 22 | 5 – 10 | 44.44 – 60 | ||||

| HA side | Mean ± SD | 15.29 ± 2.29 | 7.00 ± 2.65 | 54.80 ± 16.11 | −9.578 | 0.000 | |

| Range | 12 – 19 | 2 – 9 | 40 – 83.33 | ||||

| P | 0.313 (NS) | 0.583 (NS) | 0.992 (NS) | ||||

| Ice pick scar | Insulin side | Mean ± SD | 11.67 ± 2.08 | 7.33 ± 1.53 | 37.06 ± 7.81 | −6.500 | 0.023 |

| Range | 10 – 14 | 6 – 9 | 30 – 45.45 | ||||

| HA side | Mean ± SD | 13.00 ± 1.73 | 8.67 ± 2.89 | 34.44 ± 12.51 | −6.500 | 0.023 | |

| Range | 12 – 15 | 7 – 12 | 20 – 41.67 | ||||

| P | 0.442 (NS) | 0.519 (NS) | 0.774 (NS) | ||||

| Rolling scar | Insulin side | Mean ± SD | 20.00 ± 4.24 | 8.00 ± 2.71 | 60.63 ± 9.66 | −9.798 | 0.002 |

| Range | 15 – 24 | 4 – 10 | 50 – 73.33 | ||||

| HA side | Mean ± SD | 14.00 ± 3.83 | 7.25 ± 3.30 | 50.26 ± 13.13 | −9.000 | 0.003 | |

| Range | 9 – 17 | 3 – 11 | 35.29 – 66.67 | ||||

| P | 0.081 (NS) | 0.738 (NS) | 0.250 (NS) | ||||

| Mixed | Insulin side | Mean ± SD | 15.00 ± 3.25 | 8.00 ± 2.58 | 46.10 ± 14.51 | −10.340 | 0.000 |

| Range | 9 – 21 | 3 – 12 | 21.43 – 80 | ||||

| HA side | Mean ± SD | 13.75 ± 3.00 | 7.19 ± 2.01 | 46.47 ± 14.78 | −8.656 | 0.000 | |

| Range | 8 – 18 | 3 – 11 | 22.22 – 70.59 | ||||

| P | 0.267 (NS) | 0.328 (NS) | 0.944 (NS) | ||||

P > 0.05: Non significant (NS); P < 0.05: Significant (S); P < 0.01: highly significant (HS)

HA = hyaluronic acid.

Patient Satisfaction

Grade 3 improvement on the insulin side was reported by 14 patients and 12 on the HA side, grade 2 by eight patients on the insulin side and nine on the HA side, grade 1 by four patients on the insulin side and four on the HA side, and grade 0 by four patients on the insulin side and five on the HA side, with non-significant difference between the insulin and HA sides regarding patient satisfaction (P = 0.616).

Side Effects

All the cases had erythema on the first day after the procedure. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation on both sides of the face was noticed in one patient only. The pain score ranged from 2 to 6, and none of the patients had clinical or lab evidence of hypoglycemia.

Discussion

Management of atrophic acne scars represents a therapeutic challenge for dermatologists, with no available standard effective treatment option [12]. Microneedling has gained marked popularity in the dermatology field for acne scar management, especially in the skin-of-color population. The microneedling process can stimulate new collagen, elastin, and new capillary formation in the papillary dermis. Several clinical studies have documented the efficacy of microneedling in acne scar management regardless of scar type or severity [13].

In the current research, the qualitative scoring of Goodman and Baron was significantly improved in the insulin side, with P <0.001, and the quantitative scoring decreased from 15.80 ± 3.91 to 7.87 ± 2.30, with 49.18% improvement.

On reviewing the literature, a few published studies have evaluated the efficacy of microneedling with topical insulin for treatment of post-acne scars. Pawar and Singh [14] used PRP with microneedling on the left side of the face and topical insulin with microneedling on the right side of the face (Actrapid insulin 40 IU/ml). The treatment protocol included four sessions at monthly intervals. To measure the progress, a qualitative grading system was used, with 45% improvement on the right side of the face (insulin) and only 26% improvement on the left (PRP). They concluded that both treatment modalities were associated with significant reduction in atrophic acne scars.

Also, Abbas et al. [15] conducted a split-face study to compare topical vitamin C with microneedling versus topical insulin (human Actrapid insulin 100 IU/ml solution) with microneedling for atrophic post-acne scar treatment. They did four sessions at monthly intervals. Statistically significant improvement in the value of ASAS on both sides of the face, with a slightly more improvement on the side treated with vitamin C, was noticed in their study.

Insulin is recognized now an as important factor in the wound healing process. It acts on growth hormone receptors that are present in the skin, thus increasing re-epithelialization, collagen content, granulation tissue formation, and insulin-like growth factor production by fibroblasts [16]. In diabetic foot management, topical application of insulin improved re-epithelization rates [17]. This effect is achieved via regulation of the inflammatory process, reduction in reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in the tissue, and induction of chemotaxis [16]. Moreover, intralesional injection and topical insulin spray prevented hypertrophic scar development after wound injuries in susceptible individuals [18].

On the HA-treated side in our study, the qualitative scoring of Goodman and Baron was significantly improved, with P < 0.001, and the quantitative scoring decreased from 14.07 ± 2.83 to 7.30 ± 2.34, with a 47.72% improvement.

The efficacy of microneedling with non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid was assessed by Amer et al. [19], who compared combined microneedling with PRP on the right side against microneedling and non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid on the left side of the face. The cases received four sessions at consecutive monthly intervals, showiing an improvement of 85.4% on the right side and 82.9% on the left side. This demonstrates that microneedling with non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid is effective in treating atrophic post-acne scars.scars.

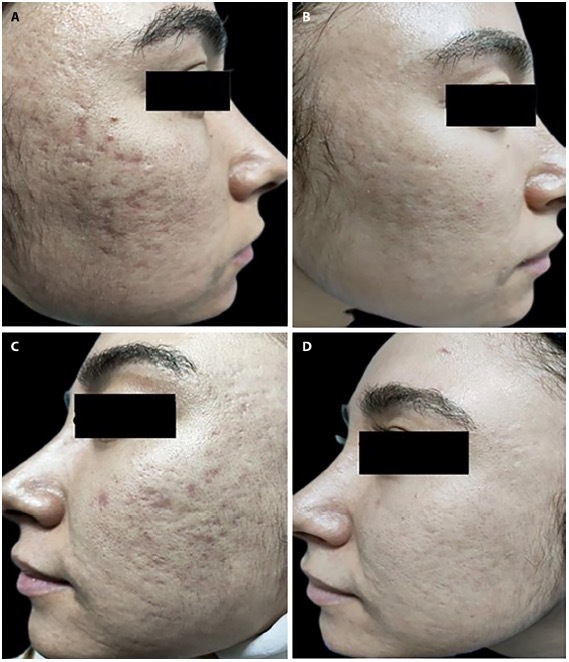

A 29-year-old woman with acne scars of 5 years’ duration. (A) Insulin side before treatment. (B) Insulin side 3 months after the last session. (C) Hyaluronic acid side before treatment. (D) Hyaluronic acid side 3 months after the last session.

The suggested mechanisms of acne scar improvement with topical HA include maintenance of skin hydration, increased keratinocyte proliferation, migration, differentiation, and increased epidermal thickness [20].

Regarding clinical improvement according to scar type in the current study, box car and rolling scars showed highly significant improvement after treatment on both sides of the face, while ice pick scars showed the least percentage of improvement. This is in agreement with Chawla, who conducted a split-face comparative study of microneedling with PRP versus microneedling with vitamin C in treating atrophic post-acne scars. He concluded that microneedling combined with PRP or vitamin C was effective in treating boxcar and rolling scars but had limited efficacy in dealing with ice pick scars [21].].

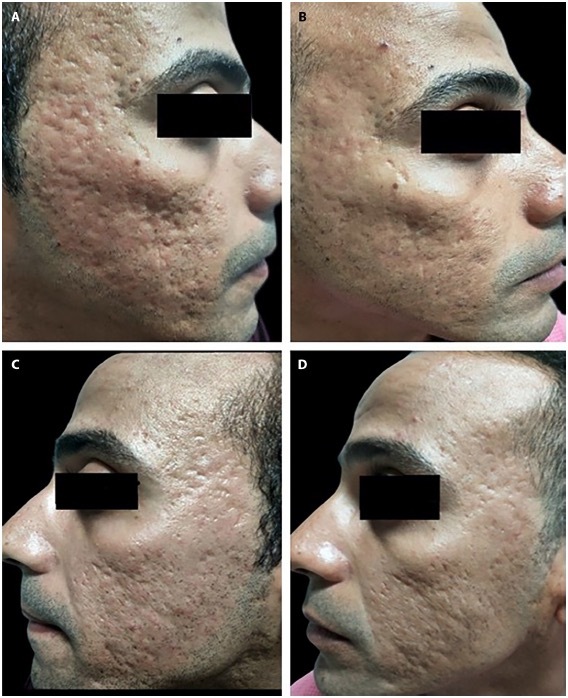

A 32-year-old man with mixed acne scars of 8 years’ duration. (A) Insulin side before treatment. (B) Insulin side 3 months after the last session. (C) Hyaluronic acid side before treatment. (D) Hyaluronic acid side 3 months after the last session.

The current study is the first of its kind to compare microneedling with topical insulin and microneedling with non-cross-linked HA for atrophic facial post-acne scar treatment. As measured by the Goodman and Baron grading system and patient satisfaction, both sides of the face showed a statistically significant decrease in the severity of post-acne scars and significant patient satisfaction.

Limitations

Our study’s strengths include the use of combination therapy, a treatment protocol composed of six sessions at three-week intervals, and all types of scars included in the treatment protocol except hypertrophic scars.

Our limitations include the absence of a control group (microneedling alone) and the relatively short follow-up period.

Conclusion

Both microneedling with topical insulin and with non-cross-linked HA is an efficient and safe therapy for atrophic post-acne scars, with a slight predilection for insulin due to its low cost and availability. Topical insulin can be considered an anti-scarring drug, but further studies on a larger scale with longer follow-up periods are required.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing Interests: None.

Authorship: All authors have contributed significantly to this publication.

References

Articles from Dermatology Practical & Conceptual are provided here courtesy of Mattioli 1885

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Combined autologous platelet-rich plasma with microneedling versus microneedling with non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid in the treatment of atrophic acne scars: Split-face study.

Dermatol Ther, 34(1):e14457, 06 Dec 2020

Cited by: 13 articles | PMID: 33107665

Microneedling With Topical Insulin Versus Microneedling With Placebo in the Treatment of Postacne Atrophic Scars: A Randomized Control Trial.

Dermatol Surg, 23 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39442178

Microneedling with topical vitamin C versus microneedling with topical insulin in the treatment of atrophic post-acne scars: A split-face study.

Dermatol Ther, 35(5):e15376, 21 Feb 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 35150195

Successful Topical Application of Botulinum Toxin After Microneedling Versus Microneedling Alone for the Treatment of Atrophic Post Acne Scars: A Prospective, Split-face, Controlled Study.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol, 15(7):26-31, 01 Jul 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 35942010 | PMCID: PMC9345194

1

1