Abstract

Free full text

The Bidirectional Relationship Between Sleep Disturbance and Functional Dyspepsia: A Systematic Review to Understand Mechanisms and Implications on Management

Abstract

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a prevalent chronic digestive disorder that significantly impacts patients' quality of life. Sleep disturbance (SD) is common among FD patients, yet the relationship between SD and FD remains poorly characterized. This systematic review explores the bidirectional relationship between FD and SD, investigating underlying mechanisms and implications for management. A rigorous and comprehensive systematic search was conducted across PubMed, PubMed Central (PMC), Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, and ScienceDirect using select keywords related to SD and FD. Only studies published in English from the past 10 years that met inclusion and exclusion criteria were included. Quality assessment tools specific to study types were employed to minimize bias. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria and quality assessments, the review encompassed 30 studies. The key findings reveal that FD is frequently associated with SD, with a significant proportion of FD patients reporting poor sleep quality. The mechanisms linking SD and FD are complex, involving the circadian rhythm, visceral hypersensitivity, immune responses, and psychological factors. Nonpharmacological treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), acupuncture, and pharmacological neuromodulators have shown promise in managing FD and SD, offering hope for improved patient outcomes. SD and FD share a significant bidirectional relationship, influenced by a complex interplay of physiological, psychological, and lifestyle factors. Addressing SD in FD patients may improve overall symptom management. Further research is crucial, as it should focus on isolating specific SD causes and their direct impacts on FD and other functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), opening up new avenues for understanding and treatment.

Introduction and background

Indigestion, one of the most prevalent chronic digestive disorders, is a significant concern [1]. It may be due to an underlying condition that is detected or causes that cannot be detected, called functional dyspepsia (FD) [1]. FD is prevalent in approximately 10% of the United Kingdom and Canadian population, with a higher prevalence in the United States at approximately 12% [1]. This high prevalence underscores the urgent need for a deeper understanding and effective management of FD.

Rome IV criteria define FD as bothersome epigastric pain or burning at least once a day per week called epigastric pain syndrome (EPS), bothersome early satiety or postprandial fullness occurring at least three days per week called postprandial distress syndrome (PDS), or an overlap disorder termed EPS-PDS [2,3].

FD, a prevalent chronic digestive disorder, significantly impacts individuals' lives. It increases unnecessary healthcare usage, may cause somatoform-type behavior, and significantly impacts psychological well-being and quality of life. This includes higher rates of absenteeism from employment, lower productivity at work, reduced productivity at home, and increased medical and prescription medicine costs every year [4]. These implications underscore the need for a comprehensive approach to managing and treating FD.

FD frequently coexists with other functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). These FGIDs may be associated concurrently with other non-gastrointestinal symptoms, including sleep disturbance (SD), anxiety, and depression, which can contribute to the maintenance or even progression of FGIDs [5].

While FD rarely leads to mortality, it significantly impacts the quality of life, with as many as 68% of patients reporting poor sleep quality [6]. There is evidence that points to a direct association between psychological distress and FD, although these studies are limited. However, SD, a common problem in FD patients, has a known association with and may influence the severity of dyspepsia symptoms [7].

Sleep is necessary for life and essential to physical and psychological health. The circadian rhythm regulates it. Over time, new lifestyles, such as shift work and overuse of electronic devices before bed, have adversely affected sleep [8]. Although SD is frequently found in patients with FGIDs, it is difficult to determine the cause and effect of the disturbances. However, we do know that SD worsens gastrointestinal symptoms, and conversely, many gastrointestinal diseases affect the sleep-wake cycle and lead to poor sleep [9].

Unlike GERD and IBS, the SD and FD relationship is still poorly characterized [10]. Although many studies have shown their association, how they contribute to symptom development or severity with each other has yet to be well documented. This study aims to provide insights into the bidirectional relationship between FD and SD and hopefully also provide evidence of the need for novel therapeutic approaches in persons suffering from both conditions.

Review

This study is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [11].

Eligibility criteria

This review question was formulated based on the participants, intervention, and outcome (PIO) elements: participants, patients diagnosed with FD or SD; intervention, investigating the bidirectional relationship between SD and dyspepsia, including exploring the impact of sleep quality on dyspepsia and the influence of dyspepsia on sleep patterns; and outcome, understanding the mechanisms underlying the bidirectional relationship between SD and dyspepsia such as alterations in neurotransmitter pathways, circadian rhythms, stress response, and gut-brain interactions. Additionally, exploring the implications of this relationship on managing dyspepsia and SD includes developing holistic management strategies targeting both conditions. Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria were added. Inclusion criteria were as follows: studies with human participants, English language (or include translations), and free full-text articles published within the past 10 years. In contrast, exclusion criteria were as follows: animal studies, papers published in languages other than English (without available translations), publications before 2014, and studies in persons without SD or FD.

Databases and search strategy

The search was conducted systematically using PubMed, PubMed Central (PMC), Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, and ScienceDirect databases. The last search of all the databases was performed on June 26, 2024. The key terms used in the search engines were sleep disturbance, functional dyspepsia, and the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) strategy used in PubMed. Details of the databases and search strategies can be found in Table Table11.

Table 1

| Database | Keywords | Search strategy | No. of articles before filters | Filters | Search result |

| PubMed | Sleep, sleep disturbance, sleep quality, insomnia, dyspepsia, indigestion | Sleep disturbance OR Sleep OR Sleep Quality OR ((("Sleep"[Majr]) OR (“Sleep Wake Disorders/drug therapy"[Mesh] OR “Sleep Wake Disorders/metabolism"[Mesh] OR “Sleep Wake Disorders/microbiology"[Mesh])) OR "Sleep Quality"[Mesh]) OR "Sleep Initiation and Maintenance Disorders"[Mesh] AND Functional Dyspepsia OR Dyspepsia OR Indigestion OR "Dyspepsia"[Majr]) OR "Dyspepsia"[Mesh] | 17002 | Free full text, ten years, humans, English | 1410 |

| PubMed Central (PMC) | Sleep disturbance, functional dyspepsia | Sleep Disturbance AND Functional Dyspepsia | 1536 | Open access, ten years | 718 |

| Google Scholar | Sleep disturbance, functional dyspepsia | “Sleep Disturbance” AND “Functional Dyspepsia” | 1320 | English, ten years | 872 |

| Cochrane Library | Sleep disturbance, functional dyspepsia | Sleep AND “Dyspepsia” | 200 | English, ten years | 102 |

| ScienceDirect | Sleep disturbance, functional dyspepsia | Sleep Disturbance AND Functional Dyspepsia | 1977 | Open access, English, ten years | 102 |

All references were grouped and organized using EndNote, and duplicate removal was done manually by EndNote. The records were manually screened based on the titles and abstracts, and irrelevant studies were excluded. The full-text articles for applicable studies were retrieved. All authors independently examined each article that was successfully retrieved according to the appropriate screening tool for quality appraisal to minimize the risk of bias in this study.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The full articles retrieved were assessed for quality assessment and risk of bias using tools depending on the study type: case-control and cohort studies, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS); cross-sectional studies, Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional studies (AXIS) Critical Appraisal; narrative reviews, Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles 2 (SANRA 2); and systematic reviews and meta-analyses, Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR 2). The assessment tools differed in their criteria and passing scores. For the paper to be accepted, a 70% score was required for each assessment tool. After completing the quality appraisal, 28 articles were included in this systematic review. Two authors agreed on which data to extract from the included articles.

Results

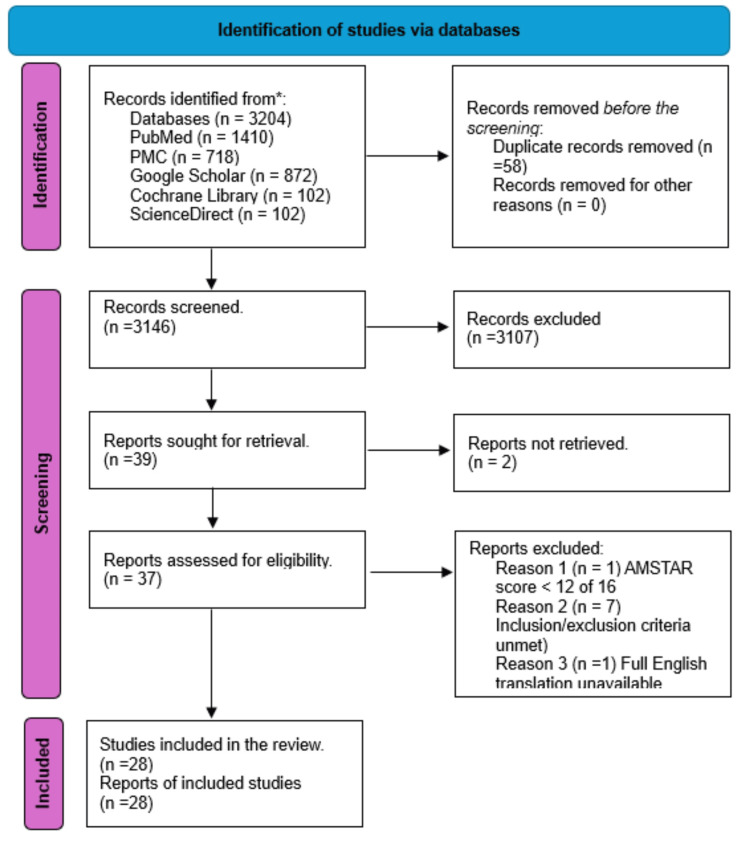

This systematic review was carried out per the PRISMA criteria, which were used to screen and narrow down studies incorporated in this systematic review. It is outlined below in Figure Figure11.

Figure 1

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Five databases were used to search for articles relevant to this study: PubMed, PMC, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, and ScienceDirect. A thorough search was performed using the MeSH strategy outlined above and relevant regular keywords, which yielded 3204 results. From these, 41 studies were sought for retrieval, of which two were not retrieved; we subsequently applied our inclusion and exclusion criteria in addition to performing a quality appraisal for each study. This resulted in nine studies being eliminated, and ultimately, 28 studies were included in this systematic review. Table Table22 below briefly describes the included studies regarding funding, population, setting, intervention, comparison, and outcomes.

Table 2

IBS: irritable bowel syndrome; FD: functional dyspepsia; CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy; QOL: quality of life; SF-36: Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey

| Author | Funding | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Setting | Outcome |

| Arnaout et al. [1] | Not specified | Adults in low- and middle-income countries | None (observational study) | None (cross-sectional study) | International, low- and middle-income countries | Prevalence and risk factors of FD |

| Barberio et al. [2] | Not specified | Patients diagnosed with Rome IV IBS and FD | None (observational study) | IBS alone vs. FD alone vs. overlap of both | Clinical setting, longitudinal follow-up | Natural history and clinical outcomes |

| Futagami et al. [3] | Yes | Patients with FD according to Rome IV criteria | None (observational study) | Subtypes of FD | Clinical setting | Classification and characteristics of FD subtypes |

| Barberio et al. [4] | Not specified | Global population with uninvestigated dyspepsia | None (meta-analysis) | Prevalence rates according to Rome criteria | Various studies included in the meta-analysis | Prevalence of uninvestigated dyspepsia |

| Colombo et al. [5] | Not specified | Children and adolescents with heartburn, FD, and/or IBS | None (observational study) | Presence vs. absence of sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression | Clinical setting | Correlation of heartburn with sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression |

| Huang et al. [6] | Not specified | Patients with FD | None (observational study) | Patients with sleep impairment vs. those without | Clinical setting | Correlation between sleep impairment and FD |

| Li et al. [7] | Not specified | Patients with FD diagnosed based on Rome III criteria | None (observational study) | Patients with sleep disturbances and psychological distress vs. those without | Clinical setting | Association between sleep disturbances, psychological distress, and FD |

| Li et al. [8] | Not specified | Patients experiencing sleep deprivation | Observation of sleep deprivation effects | NA | Clinical and experimental settings | Changes in gastrointestinal physiology and disease outcomes |

| Khanijow et al. [9] | Not specified | Patients with various gastrointestinal diseases | Observation of sleep dysfunction | Patients with and without sleep dysfunction | Clinical setting | Association between sleep dysfunction and gastrointestinal disease symptoms |

| Grover et al. [10] | Not specified | Patients with FD | Observation of sleep disturbances | Patients with and without sleep disturbances | Clinical setting | Correlation of sleep disturbances with FD symptoms |

| Alonso-Bermejo et al. [12] | Not specified | General population meeting Rome IV criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders | Observation of prevalence | None | Community-based setting | Frequency of various functional gastrointestinal disorders |

| Zhao et al. [13] | Not specified | Patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders in class 3 hospitals in Tianjin, China | Observation of sleep quality | Patients with varying sleep quality | Hospital-based setting | Association between sleep quality and gastrointestinal disorder symptoms |

| Hyun et al. [14] | Not specified | General community with digestive symptoms | Observation of sleep disturbances | Individuals with and without sleep disturbances | Community-based setting | Correlation between digestive symptoms and sleep disturbances |

| Khan et al. [15] | Not specified | FD patients in a tertiary care hospital | Observation of sleep quality | Patients with varying sleep quality | Tertiary care hospital | Relationship between sleep quality and FD |

| Morito et al. [16] | Not specified | Individuals with abdominal symptoms | Observation of sleep disturbances | Individuals with and without sleep disturbances | Clinical setting | Correlation between sleep disturbances and abdominal symptoms |

| Su et al. [17] | Not specified | Patients with sleep disturbances | Observation of FD risk | Patients with and without sleep disturbances | Population-based cohort | Relative risk of FD |

| Topan and Scott [18] | Not specified | Individuals with disorders of gut-brain interaction | Observation of sleep patterns | Individuals with and without sleep disturbances | Clinical and research settings | Impact of sleep on gut-brain interaction disorders |

| Tseng and Wu [19] | Not specified | Rotating shift workers | Observation of circadian rhythm and sleep disturbance | Individuals with regular vs. rotating shifts | Occupational setting | Impact on gastrointestinal dysfunction |

| Du et al. [20] | Not specified | Patients with FD | Measurement of duodenal eosinophil degranulation | Patients with and without eosinophil degranulation | Clinical setting | Association between eosinophil degranulation and FD |

| Fowler et al. [21] | Not specified | Patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction | Observation of circadian rhythms and melatonin metabolism | Patients with normal vs. disrupted circadian rhythms | Clinical and research settings | Impact on gut-brain interaction disorders |

| Ermis et al. [22] | Not specified | Male patients with FD | Measurement of melatonin levels | Patients with varying melatonin levels | Clinical setting | Role of melatonin in FD pathogenesis |

| Fang et al. [23] | Not specified | Patients with FD | Observation of subgroups based on Rome III criteria | Different subgroups of FD | Clinical setting | Distinct aetiopathogenesis |

| Koloski et al. [24] | Not specified | Patients with IBS and FD | Observation of gut-brain and brain-gut pathways | Pathways in patients with IBS vs. FD | Population-based prospective studies | Independent pathways operating in IBS and FD |

| Nakamura et al. [25] | Yes | 20 patients with FD and sleep disturbance | Administration of sleep aids for four weeks (zolpidem, eszopiclone, and suvorexant) | Pre- and post-intervention comparison of sleep quality and gastrointestinal symptoms | Clinical setting | Significant improvement in sleep quality and gastrointestinal symptoms. Improvement in QOL assessed by the SF-36. Significant reduction in anxiety scores |

| Law et al. [26] | Not specified | Patients with gastroduodenal disorders | CBT-based interventions | CBT interventions vs. other treatments | Various clinical trials included in the review | Effectiveness of CBT on gastroduodenal disorders |

| Ho et al. [27] | Not specified | Patients with FD | Acupuncture and related therapies | Acupuncture vs. prokinetics | Various studies included in the meta-analysis | Effectiveness of therapies on FD |

| Masuy et al. [28] | Not specified | Patients with FD | Various treatment options | Different treatments for FD | Review of clinical studies | Effectiveness and outcomes of treatments |

| Adibi et al. [29] | Yes | Individuals with and without FD | Observation of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress | FD patients vs. non-FD individuals | Community-based setting | Association between psychological factors and FD |

Discussion

FD, a subset of FGIDs, is defined by the presence of dyspeptic symptoms, namely, epigastric pain or burning, and postprandial discomfort or early satiety, in a patient with no identifiable organic cause on an investigation, namely, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy [12]. FGIDs include IBS, functional constipation (FC), GERD, and other symptoms associated with no structural or organic cause as classified by the Rome IV criteria for FGIDs. Compared to other FGIDs, FD patients have more trouble sleeping [13]. SD encompasses a variety of disorders that have all been documented in persons with a diagnosis of FD, including insomnia, hypersomnia, circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders, sleep apnea, narcolepsy and cataplexy, parasomnia, and sleep-related movement disorders [14].

Digestive problems and sleep deprivation are frequently associated, but there is a complicated link between them. Dyspeptic symptoms, like abdominal pain, may make it difficult to fall asleep or postpone sleep onset, while insufficient sleep may worsen dyspepsia symptoms. A recent meta-analysis showed that individuals with postprandial distress (51%) and epigastric pains (40%) had a greater generalized incidence of sleep disruption [15]. Fass and colleagues found that 57.2% of patients studied with IBS and FD reported abdominal pain and discomfort that woke them from sleep. On the other hand, sleep deprivation has been reported to enhance gastrointestinal sensitivity and aggravate unpleasant abdominal symptoms [9,15]. This vicious cycle may explain the heightened symptoms of FD in patients with coexistent SD.

While the interrelation between SD and FD has been studied, its underlying mechanism is complex. Emerging insight into the pathophysiology of FD suggests that the circadian rhythm, visceral hypersensitivity, the immune system, and intestinal dysmotility are primary players in its pathogenesis [9,16]. The proposed underlying mechanisms emphasize the bidirectional system of our brain and gastrointestinal tract.

The circadian rhythm

Several brain regions regulate the sleep-wake state. The circadian rhythm originates in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and regulates sleep-wake through hormones like melatonin and serotonin. The raphe nuclei are also involved in the circadian rhythm through their interaction with serotonin. The raphe nuclei receive signals from the gut's enteric nervous system via serotonergic, cholinergic, and noradrenergic pathways and, in turn, send signals to the dorsal column of the spinal cord that regulates gut motility and pain sensation. Serotonin, as a neurotransmitter, also enhances the activity of prokinetic neuropeptides in the gastrointestinal tract. Interference of these pathways through a sleep-wake cycle disturbance might affect gut motility. Overstimulating such pathways may cause hypersensitivity and bowel discomfort such as nausea, pain, or bloating [9,16,17].

Visceral hypersensitivity

Visceral hypersensitivity is a constant feature of FGIDs [18]. However, the mechanisms driving the response need to be better understood. There is a probable association with melatonin, which reduces pain symptoms of IBS by regulating the sleep-wake state. It's also plausible that poor sleep may affect the upper gastrointestinal tract, and the relationship between sleep and IBS may also apply to FD [17,18]. Night-time awakening disrupts sleep. This is frequently accompanied by emotional instability and psychosocial comorbidities that may induce visceral hypersensitivity, hyperalgesia, and hypervigilance, contributing to the symptoms in patients who suffer from FD [19].

The immune system

Eosinophil-mast cell-nerve interactions have an essential role in generating dyspeptic symptoms. Tryptase released from degranulated mast cells induces intestinal epithelial breakdown, activates other inflammatory cells, and raises visceral hypersensitivity in the intestinal tract. This low-grade mucosal inflammation, characterized by increased duodenal eosinophilia and mast cells in FD, may result from circadian disruption. However, this has mainly been unexplored so far [20,21]. Immune dysregulation causing FD could also be related to melatonin levels. Melatonin inhibits the acute neutrophilic response of inflammation. It maintains mucosal cell integrity by reducing neutrophil-mediated damage, suggesting alterations in melatonin release associated with irregular sleep patterns may contribute to inflammation [21,22]. However, it's important to note that the relationship between melatonin and the immune gastrointestinal response is much more complicated.

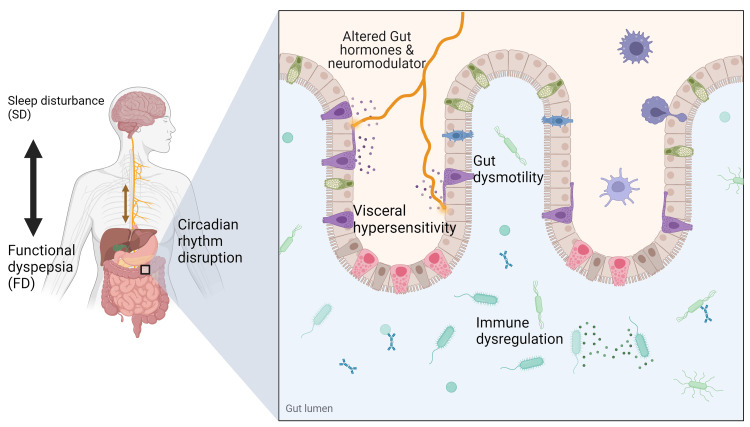

Figure Figure22 below shows the bidirectional communication between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract, highlighting the main effects of SD on the circadian rhythm and gastrointestinal system.

Figure 2

Gut-brain interaction and bidirectional relationship of SD and FD. SD alters the circadian rhythm, affecting the release of neuromodulators and hormones such as melatonin, causing altered gut motility, visceral hypersensitivity, and immune dysregulation. Altered gut motility causing early satiety and abdominal discomfort is called PDS. Visceral hypersensitivity and immune dysregulation are associated with epigastric pain and are referred to as EPS. Sometimes with overlap (PDS-EPS). Symptoms of FD may cause waking or increased sleep latency, causing SD. Created with Biorender.com

SD: sleep disturbance; FD: functional dyspepsia; PDS: postprandial distress syndrome; EPS: epigastric pain syndrome

Psychological and behavioral factors

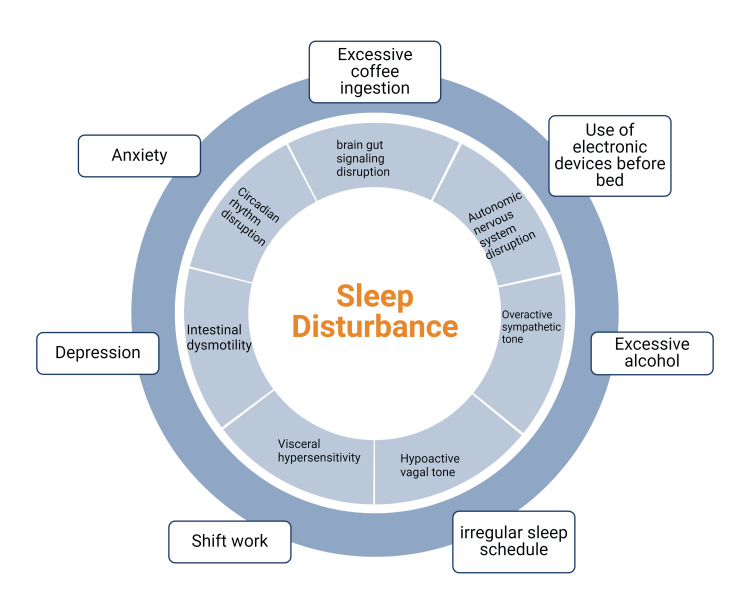

Behavioral and lifestyle factors contributing to SD, such as coffee drinking, excessive alcohol intake, use of electronic devices before bed, anxiety, and depression, have also been linked with FD. This might be due to a disruption of brain-gut signaling and dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, including an overactive sympathetic tone and a hypoactive vagal tone, which leads to visceral hypersensitivity and dyspeptic symptoms [23,24]. The autonomic dysfunction associated with depression might impair gastric accommodation and produce symptoms of FD, specifically the PDS subtype of the disease [23,24]. However, the gut and brain interact bidirectionally in FD. In people without FD, higher levels of anxiety and depression were significant predictors of developing IBS and FD. Also, between one-third and two-thirds of patients with FGIDs have a primary gut-driven syndrome that goes on to affect the brain [24]. Hypothesized pathways of gut-brain communication include direct secretion of neuroactive chemicals in the gut by bacteria, such as serotonin precursors, and stimulation of secretion of serotonin from enteroendocrine cells [24]. Figure Figure33 below highlights common lifestyle factors associated with SD and their effect on the gastrointestinal tract.

Figure 3

Common lifestyle factors affecting circadian rhythm and ultimately leading to SD. SD, in turn, has multiple effects on the gastrointestinal tract, which may cause or enhance symptoms of FD. Created with Biorender.com

SD: sleep disturbance; FD: functional dyspepsia

Therapeutic interventions, including nonpharmacological treatments

The connection between SD and FD continues to grow, with evidence showing that the use of sleep-inducing drugs is associated with reduced pain and overall improvement of dyspeptic symptoms in FD patients. So, it might be necessary to evaluate for SD in patients with FD and vice versa. If so, sleep aids may work for FD and SD [25]. There is a higher incidence of behavioral abnormalities and SD in patients with FD than those without FD. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is effective in patients with FD and SD. CBT-based interventions are associated with improvements in depression, anxiety, stress, health-related quality of life, and gastrointestinal symptoms [26]. Increased sensory signals from the gut and impaired central modulation of pain and gut functions are critical pathogenic features among FD patients. Acupuncture is a therapeutic approach suggested to modulate the brain-gut axis and restore homeostasis. This potential mechanism might explain the effectiveness of acupuncture for managing FD [27]. As the name implies, the brain‐gut axis is a bidirectional communication pathway between the brain and the gut, connecting the central and enteric nervous systems. This pathway is frequently disturbed in patients who experience SD. Neuromodulators, like antidepressants and anxiolytics, are second-line drugs indicated for refractory FD symptoms through their pain‐modulating potential on the brain-gut axis. Psychiatric comorbidities that are associated with SD, such as depression or anxiety disorders, frequently coexist with FD, for which neuromodulators are used. Although several have been studied, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are the most effective [28].

SD and FD share a bidirectional relationship. However, other factors also play a role, and the current study has limitations. Psychological factors, such as stress, anxiety, and depression, affect both conditions [29]. More research is needed to assess the specific causes of SD and its relationship with FD. Rome IV criteria increased the sensitivity for the diagnosis of FD by introducing a third category of FD with an overlap of symptoms. This new category, PDS-EPS overlapped syndrome, increased the sensitivity of FD detection [3]. Our data set included research dating back to 2014, before the introduction of Rome IV, which may have caused some heterogeneity in how FGIDs are classified among studies included in this review.

Conclusions

The systematic review highlights a significant bidirectional relationship between SD and FD. There is evidence suggesting that individuals with SD are more likely to experience FD and, conversely, those with FD are more likely to suffer from SD. A complex interplay of physiological, psychological, and lifestyle factors influences this relationship. SD affects the circadian rhythm, alters visceral sensitivity, and affects the immune system. Nonpharmacological treatment modalities such as CBT, acupuncture, and pharmacological neuromodulators are effective at improving symptoms of SD and FD and may be the best option for patients with both conditions. More research is needed to isolate the relationship between specific causes of SD, such as insomnia, hypersomnia, circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders, sleep apnea, narcolepsy and cataplexy, parasomnia, sleep-related movement disorders, and their association with other FGIDs.

Disclosures

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Alvin Billey, Asra Saleem, Bushra Zeeshan, Meaza F. Zergaw, Sondos T. Nassar

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Alvin Billey, Gayanthi Dissanayake, Mohamed Elgendy

Drafting of the manuscript: Alvin Billey, Asra Saleem, Gayanthi Dissanayake, Meaza F. Zergaw, Sondos T. Nassar

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Alvin Billey, Bushra Zeeshan, Mohamed Elgendy, Sondos T. Nassar

Supervision: Alvin Billey, Sondos T. Nassar

References

Articles from Cureus are provided here courtesy of Cureus Inc.

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Acupuncture for functional dyspepsia.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, (10):CD008487, 13 Oct 2014

Cited by: 28 articles | PMID: 25306866 | PMCID: PMC10558101

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Food and functional dyspepsia: a systematic review.

J Hum Nutr Diet, 31(3):390-407, 15 Sep 2017

Cited by: 38 articles | PMID: 28913843

Review

Sleep disturbance and psychological distress are associated with functional dyspepsia based on Rome III criteria.

BMC Psychiatry, 18(1):133, 18 May 2018

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 29776354 | PMCID: PMC5960153

Functional Dyspepsia: Current Understanding and Future Perspective.

Digestion, 105(1):26-33, 18 Aug 2023

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 37598673

Review

1

1