Abstract

Background

Paclitaxel is an antineoplastic agent used to treat breast, lung, endometrial, cervical, pancreatic, sarcoma, and thymoma cancer. However, drugs that induce, inhibit, or are substrates of cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes 2C8 or 3A4 may alter the metabolism of paclitaxel, potentially impacting its effectiveness. The purposes of this study are to provide an overview of paclitaxel use, identify potential drugs that interact with paclitaxel, and describe their clinical manifestations.Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed on patients receiving paclitaxel to evaluate types and stages of cancer, treatment regimens, and adverse events of paclitaxel alone or paclitaxel in combination with other antineoplastic drugs, using data retrieved in March 2022 from the US Department of Defense Cancer Registry. Additionally, the study compared the health issues and prescriptions of patients who completed treatment with those who discontinued treatment. It evaluated interactions of paclitaxel with noncancer drugs, particularly antidepressants metabolizing and inhibiting CYP3A4, using data from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/Professional Encounter Record and the Pharmacy Data Transaction Service database. Data were retrieved in October 2022.Results

Of 702 patients prescribed paclitaxel, 338 completed treatment. Paclitaxel discontinuation alone vs concomitantly (P < .001) and 1 drug vs combination (P < .001) both were statistically significant. Patients who took paclitaxel concomitantly with a greater number of prescription drugs had a higher rate of treatment discontinuation than those who received fewer medications. Patients in the completed group received 9 to 56 prescription drugs, and those in the discontinued group were prescribed 6 to 70. Those who discontinued treatment had more diagnosed medical issues than those who completed treatment.Conclusions

The study provides a comprehensive overview of paclitaxel usage from 1996 through 2022 and highlights potential drug interactions that may affect treatment outcomes. While the impact of prescription drugs on paclitaxel discontinuation is uncertain, paclitaxel and antidepressants do not have significant drug-drug interactions.Free full text

Paclitaxel Drug-Drug Interactions in the Military Health System

Abstract

Background

Paclitaxel is an antineoplastic agent used to treat breast, lung, endometrial, cervical, pancreatic, sarcoma, and thymoma cancer. However, drugs that induce, inhibit, or are substrates of cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes 2C8 or 3A4 may alter the metabolism of paclitaxel, potentially impacting its effectiveness. The purposes of this study are to provide an overview of paclitaxel use, identify potential drugs that interact with paclitaxel, and describe their clinical manifestations.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed on patients receiving paclitaxel to evaluate types and stages of cancer, treatment regimens, and adverse events of paclitaxel alone or paclitaxel in combination with other antineoplastic drugs, using data retrieved in March 2022 from the US Department of Defense Cancer Registry. Additionally, the study compared the health issues and prescriptions of patients who completed treatment with those who discontinued treatment. It evaluated interactions of paclitaxel with noncancer drugs, particularly antidepressants metabolizing and inhibiting CYP3A4, using data from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/Professional Encounter Record and the Pharmacy Data Transaction Service database. Data were retrieved in October 2022.

Results

Of 702 patients prescribed paclitaxel, 338 completed treatment. Paclitaxel discontinuation alone vs concomitantly (P < .001) and 1 drug vs combination (P < .001) both were statistically significant. Patients who took paclitaxel concomitantly with a greater number of prescription drugs had a higher rate of treatment discontinuation than those who received fewer medications. Patients in the completed group received 9 to 56 prescription drugs, and those in the discontinued group were prescribed 6 to 70. Those who discontinued treatment had more diagnosed medical issues than those who completed treatment.

Conclusions

The study provides a comprehensive overview of paclitaxel usage from 1996 through 2022 and highlights potential drug interactions that may affect treatment outcomes. While the impact of prescription drugs on paclitaxel discontinuation is uncertain, paclitaxel and antidepressants do not have significant drug-drug interactions.

BACKGROUND

Paclitaxel was first derived from the bark of the yew tree (Taxus brevifolia). It was discovered as part of a National Cancer Institute program screen of plants and natural products with putative anticancer activity during the 1960s.1–9 Paclitaxel works by suppressing spindle microtube dynamics, which results in the blockage of the metaphase-anaphase transitions, inhibition of mitosis, and induction of apoptosis in a broad spectrum of cancer cells. Paclitaxel also displayed additional anticancer activities, including the suppression of cell proliferation and antiangiogenic effects. However, since the growth of normal body cells may also be affected, other adverse effects (AEs) will also occur.8–18

Two different chemotherapy drugs contain paclitaxel—paclitaxel and nabpaclitaxel— and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognizes them as separate entities.19–21 Taxol (paclitaxel) was approved by the FDA in 1992 for treating advanced ovarian cancer.20 It has since been approved for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma (as an orphan drug), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and cervical cancers (in combination with bevacizumab) in 1994, 1997, 1999, and 2014, respectively.21 Since 2002, a generic version of Taxol, known as paclitaxel injectable, has been FDA-approved from different manufacturers. According to the National Cancer Institute, a combination of carboplatin and Taxol is approved to treat carcinoma of unknown primary, cervical, endometrial, NSCLC, ovarian, and thymoma cancers.19 Abraxane (nab-paclitaxel) was FDA-approved to treat metastatic breast cancer in 2005. It was later approved for first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC and late-stage pancreatic cancer in 2012 and 2013, respectively. In 2018 and 2020, both Taxol and Abraxane were approved for first-line treatment of metastatic squamous cell NSCLC in combination with carboplatin and pembrolizumab and metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in combination with pembrolizumab, respectively.22–26 In 2019, Abraxane was approved with atezolizumab to treat metastatic triple-negative breast cancer, but this approval was withdrawn in 2021. In 2022, a generic version of Abraxane, known as paclitaxel protein-bound, was released in the United States. Furthermore, paclitaxel-containing formulations also are being studied in the treatment of other types of cancer.19–32

One of the main limitations of paclitaxel is its low solubility in water, which complicates its drug supply. To distribute this hydrophobic anticancer drug efficiently, paclitaxel is formulated and administered to patients via polyethoxylated castor oil or albumin-bound (nab-paclitaxel). However, polyethoxylated castor oil induces complement activation and is the cause of common hypersensitivity reactions related to paclitaxel use.2,17,33–38 Therefore, many alternatives to polyethoxylated castor oil have been researched.

Since 2000, new paclitaxel formulations have emerged using nanomedicine techniques. The difference between these formulations is the drug vehicle. Different paclitaxel-based nano-technological vehicles have been developed and approved, such as albumin-based nanoparticles, polymeric lipidic nanoparticles, polymeric micelles, and liposomes, with many others in clinical trial phases.3,37 Albumin-based nanoparticles have a high response rate (33%), whereas the response rate for polyethoxylated castor oil is 25% in patients with metastatic breast cancer.33,39–52 The use of paclitaxel dimer nanoparticles also has been proposed as a method for increasing drug solubility.33,53

Paclitaxel is metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes 2C8 and 3A4. When administering paclitaxel with known inhibitors, inducers, or substrates of CYP2C8 or CYP3A4, caution is required.19–22 Regulations for CYP research were not issued until 2008, so potential interactions between paclitaxel and other drugs have not been extensively evaluated in clinical trials. A study of 12 kinase inhibitors showed strong inhibition of CYP2C8 and/or CYP3A4 pathways by these inhibitors, which could alter the ratio of paclitaxel metabolites in vivo, leading to clinically relevant changes.54 Differential metabolism has been linked to paclitaxel-induced neurotoxicity in patients with cancer.55 Nonetheless, variants in the CYP2C8, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and ABCB1 genes do not account for significant interindividual variability in paclitaxel pharmacokinetics.56 In liver microsomes, losartan inhibited paclitaxel metabolism when used at concentrations > 50 μmol/L.57 Many drug-drug interaction (DDI) studies of CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 have shown similar results for paclitaxel.58–64

The goals of this study are to investigate prescribed drugs used with paclitaxel and determine patient outcomes through several Military Health System (MHS) databases. The investigation focused on (1) the functions of paclitaxel; (2) identifying AEs that patients experienced; (3) evaluating differences when paclitaxel is used alone vs concomitantly and between the completed vs discontinued treatment groups; (4) identifying all drugs used during paclitaxel treatment; and (5) evaluating DDIs with antidepressants (that have an FDA boxed warning and are known to have DDIs confirmed in previous publications) and other drugs.65–67

The Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, institutional review board approved the study protocol and ensured compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act as an exempt protocol. The Joint Pathology Center (JPC) of the US Department of Defense (DoD) Cancer Registry Program and MHS data experts from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/Professional Encounter Record (CAPER) and the Pharmacy Data Transaction Service (PDTS) provided data for the analysis.

METHODS

The DoD Cancer Registry Program was established in 1986 and currently contains data from 1998 to 2024. CAPER and PDTS are part of the MHS Data Repository/Management Analysis and Reporting Tool database. Each observation in the CAPER record represents an ambulatory encounter at a military treatment facility (MTF). CAPER includes data from 2003 to 2024.

Each observation in the PDTS record represents a prescription filled for an MHS beneficiary at an MTF through the TRICARE mail-order program or a US retail pharmacy. Missing from this record are prescriptions filled at international civilian pharmacies and inpatient pharmacy prescriptions. The MHS Data Repository PDTS record is available from 2002 to 2024. The legacy Composite Health Care System is being replaced by GENESIS at MTFs.

Data Extraction Design

The study design involved a cross-sectional analysis. We requested data extraction for paclitaxel from 1998 to 2022. Data from the DoD Cancer Registry Program were used to identify patients who received cancer treatment. Once patients were identified, the CAPER database was searched for diagnoses to identify other health conditions, whereas the PDTS database was used to populate a list of prescription medications filled during chemotherapy treatment.

Data collected from the JPC included cancer treatment, cancer information, demographics, and physicians’ comments on AEs. Collected data from the MHS include diagnosis and filled prescription history from initiation to completion of the therapy period (or 2 years after the diagnosis date). For the analysis of the DoD Cancer Registry Program and CAPER databases, we used all collected data without excluding any. When analyzing PDTS data, we excluded patients with PDTS data but without a record of paclitaxel being filled, or medications filled outside the chemotherapy period (by evaluating the dispensed date and day of supply).

Data Extraction Analysis

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Coding and Staging Manual 2016 and the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition, 1st revision, were used to decode disease and cancer types.68,69 Data sorting and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel. The percentage for the total was calculated by using the number of patients or data available within the paclitaxel groups divided by the total number of patients or data variables. The subgroup percentage was calculated by using the number of patients or data available within the subgroup divided by the total number of patients in that subgroup.

In alone vs concomitant and completed vs discontinued treatment groups, a 2-tailed, 2-sample z test was used to statistical significance (P < .05) using a statistics website.70 Concomitant was defined as paclitaxel taken with other antineoplastic agent(s) before, after, or at the same time as cancer therapy. For the retrospective data analysis, physicians’ notes with a period, comma, forward slash, semicolon, or space between medication names were interpreted as concurrent, whereas plus (+), minus/plus (−/+), or “and” between drug names that were dispensed on the same day were interpreted as combined with known common combinations: 2 drugs (DM886 paclitaxel and carboplatin and DM881-TC-1 paclitaxel and cisplatin) or 3 drugs (DM887-ACT doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and paclitaxel). Completed treatment was defined as paclitaxel as the last medication the patient took without recorded AEs; switching or experiencing AEs was defined as discontinued treatment.

RESULTS

The JPC provided 702 entries for 687 patients with a mean age of 56 years (range, 2 months to 88 years) who were treated with paclitaxel from March 1996 to October 2021. Fifteen patients had duplicate entries because they had multiple cancer sites or occurrences. There were 623 patients (89%) who received paclitaxel for FDA-approved indications. The most common types of cancer identified were 344 patients with breast cancer (49%), 91 patients with lung cancer (13%), 79 patients with ovarian cancer (11%), and 75 patients with endometrial cancer (11%) (Table 1). Seventy-nine patients (11%) received paclitaxel for cancers that were not for FDA-approved indications, including 19 for cancers of the fallopian tube (3%) and 17 for esophageal cancer (2%) (Table 2).

TABLE 1

Uses of Paclitaxel by Cancer Locationa

| Cancer location | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 623 (89) |

|

| |

| Breast | 344 (49) |

Upper-outer quadrant Upper-outer quadrant | 130 (19) |

Overlapping lesion Overlapping lesion | 73 (10) |

Breast not otherwise specified Breast not otherwise specified | 45 (6) |

Upper-inner quadrant Upper-inner quadrant | 41 (6) |

Lower-inner quadrant Lower-inner quadrant | 23 (3) |

Lower-outer quadrant Lower-outer quadrant | 21 (3) |

Central portion Central portion | 9 (1) |

Axillary tail Axillary tail | 2 (< 1) |

|

| |

| Lung | 91 (13) |

Upper lobe Upper lobe | 37 (5) |

Lower lobe Lower lobe | 34 (5) |

Lung not otherwise specified Lung not otherwise specified | 8 (1) |

Main bronchus Main bronchus | 6 (1) |

Middle lobe Middle lobe | 5 (1) |

Overlapping lesion Overlapping lesion | 1 (< 1) |

|

| |

| Ovary | 79 (11) |

|

| |

| Endometrial | 75 (11) |

Endometrium Endometrium | 67 (10) |

Corpus uteri Corpus uteri | 6 (1) |

Fundus uteri Fundus uteri | 1 (< 1) |

Overlapping lesion Overlapping lesion | 1 (< 1) |

|

| |

| Cervical | 15 (2) |

Cervix uteri Cervix uteri | 13 (2) |

Endocervix Endocervix | 1 (< 1) |

Overlapping lesion Overlapping lesion | 1 (< 1) |

|

| |

| Pancreatic | 13 (2) |

Head of pancreas Head of pancreas | 7 (1) |

Body of pancreas Body of pancreas | 2 (< 1) |

Tail of pancreas Tail of pancreas | 2 (< 1) |

Pancreas not otherwise specified Pancreas not otherwise specified | 2 (< 1) |

|

| |

| Connective, subcutaneous, and other soft tissue | 4 (1) |

Head, face, and neck Head, face, and neck | 2 (< 1) |

Upper limb and shoulder Upper limb and shoulder | 1 (< 1) |

Trunk not otherwise specified Trunk not otherwise specified | 1 (< 1) |

Thymus Thymus | 2 (< 1) |

TABLE 2

Off-Label Uses of Paclitaxel by Cancer Locationa

| Cancer location | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 79 (11) |

|

| |

| Fallopian | 19 (3) |

Fallopian tube Fallopian tube | 18 (3) |

Female genital tract not otherwise specified Female genital tract not otherwise specified | 1 (< 1) |

|

| |

| Esophageal | 17 (2) |

Lower third of esophagus Lower third of esophagus | 7 (1) |

Esophagus not otherwise specified Esophagus not otherwise specified | 7 (1) |

Cervical esophagus Cervical esophagus | 1 (< 1) |

Thoracic esophagus Thoracic esophagus | 1 (< 1) |

Middle third of esophagus Middle third of esophagus | 1 (< 1) |

|

| |

| Stomach | 6 (1) |

Cardia not otherwise specified Cardia not otherwise specified | 4 (1) |

Stomach not otherwise specified Stomach not otherwise specified | 2 (< 1) |

|

| |

| Larynx | 2 (< 1) |

Glottis Glottis | 1 (< 1) |

Supraglottis Supraglottis | 1 (< 1) |

|

| |

| Total | 33 (5) |

Unknown primary site Unknown primary site | 7 (1) |

Peritoneum not otherwise specified Peritoneum not otherwise specified | 6 (1) |

Kidney not otherwise specified Kidney not otherwise specified | 4 (1) |

Uterus not otherwise specified Uterus not otherwise specified | 3 (< 1) |

Tonsil not otherwise specified Tonsil not otherwise specified | 3 (< 1) |

Anal canal Anal canal | 2 (< 1) |

Glans penis Glans penis | 1 (< 1) |

Prostate gland Prostate gland | 1 (< 1) |

Undescended testis Undescended testis | 1 (< 1) |

Posterior wall of bladder Posterior wall of bladder | 1 (< 1) |

Urethra Urethra | 1 (< 1) |

Lower gum Lower gum | 1 (< 1) |

Cheek mucosa Cheek mucosa | 1 (< 1) |

Parotid gland Parotid gland | 1 (< 1) |

There were 477 patients (68%) aged > 50 years. A total of 304 patients (43%) had a stage III or IV cancer diagnosis and 398 (57%) had stage II or lower (combination of data for stages 0, I, and II; not applicable; and unknown) cancer diagnosis. For systemic treatment, 16 patients (2%) were treated with paclitaxel alone and 686 patients (98%) received paclitaxel concomitantly with additional chemotherapy: 59 patients (9%) in the before or after group, 410 patients (58%) had a 2-drug combination, 212 patients (30%) had a 3-drug combination, and 5 patients (1%) had a 4-drug combination. In addition, for doublet therapies, paclitaxel combined with carboplatin, trastuzumab, gemcitabine, or cisplatin had more patients (318, 58, 12, and 11, respectively) than other combinations (≤ 4 patients). For triplet therapies, paclitaxel combined with doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide or carboplatin plus bevacizumab had more patients (174 and 20, respectively) than other combinations, including quadruplet therapies (≤ 4 patients) (Table 3).

TABLE 3

Paclitaxel Use in Military Health System Cancer Registry Database

| Drugs | Total, No. (%) | Completed without AEs, No. (%) | Discontinued with AEs, No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 702 (100) | 338 (48) | 364 (52) |

|

| |||

| Treatment | |||

Alone Alone | 16 (2) | 16 (5) | 0 (0) |

Concomitant Concomitant | 686 (98) | 322 (95) | 364 (100) |

Before or after Before or after | 59 (8) | 4 (1) | 55 (15) |

Paclitaxel + other medications Paclitaxel + other medications | 627 (89) | 318 (94) | 309 (85) |

|

| |||

| Paclitaxel + 1 medication | 410 (58) | 222 (66) | 188 (52) |

Carboplatin Carboplatin | 318 (45) | 182 (54) | 136 (37) |

Trastuzumab Trastuzumab | 58 (8) | 23 (7) | 35 (10) |

Gemcitabine Gemcitabine | 12 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) |

Cisplatin Cisplatin | 11 (2) | 6 (2) | 5 (1) |

Trastuzumab-dttb Trastuzumab-dttb | 4 (1) | 1 (< 1) | 3 (1) |

Bevacizumab Bevacizumab | 3 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (1) |

Cetuximab Cetuximab | 2 (< 1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

Cyclophosphamide Cyclophosphamide | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) |

Ramucirumab Ramucirumab | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

|

| |||

| Paclitaxel + 2 medications | 212 (30) | 93 (28) | 119 (33) |

Doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide Doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide | 174 (25) | 78 (23) | 96 (26) |

Carboplatin + bevacizumab Carboplatin + bevacizumab | 20 (3) | 6 (2) | 14 (4) |

Ifosfamide (IFEX) + cisplatin Ifosfamide (IFEX) + cisplatin | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

Carboplatin + trastuzumab Carboplatin + trastuzumab | 3 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (1) |

Cisplatin + bevacizumab Cisplatin + bevacizumab | 3 (< 1) | 2 (1) | 1 (< 1) |

Trastuzumab + pertuzumab Trastuzumab + pertuzumab | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

Carboplatin + etoposide Carboplatin + etoposide | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) |

Carboplatin + fluorouracil (5FU) Carboplatin + fluorouracil (5FU) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) |

Gemcitabine + cisplatin Gemcitabine + cisplatin | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) |

Trastuzumab-dttb + pertuzumab Trastuzumab-dttb + pertuzumab | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) |

Carboplatin + pembrolizumab Carboplatin + pembrolizumab | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) |

Cisplatin + pembrolizumab Cisplatin + pembrolizumab | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) |

|

| |||

| Paclitaxel + 3 medications | 5 (1) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) |

Carboplatin + trastuzumab + pertuzumab Carboplatin + trastuzumab + pertuzumab | 2 (< 1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

Carboplatin + doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide Carboplatin + doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) |

Doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide + pegfilgrastim Doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide + pegfilgrastim | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) |

Doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide + pembrolizumab Doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide + pembrolizumab | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) |

|

| |||

| Cancers | |||

Cancer with FDA-approved indication Cancer with FDA-approved indication | 546 (78) | 241 (71) | 305 (84) |

Off-label or other cancers Off-label or other cancers | 156 (22) | 97 (29) | 59 (16) |

Stage 0, I, II, not applicable, or unknown Stage 0, I, II, not applicable, or unknown | 398 (57) | 196 (58) | 202 (55) |

Stage III or IV Stage III or IV | 304 (43) | 142 (42) | 162 (45) |

|

| |||

| Age | |||

≤ 50 y ≤ 50 y | 225 (32) | 102 (30) | 123 (34) |

> 50 y > 50 y | 477 (68) | 236 (70) | 241 (66) |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration.

Patients were more likely to discontinue paclitaxel if they received concomitant treatment. None of the 16 patients receiving paclitaxel monotherapy experienced AEs, whereas 364 of 686 patients (53%) treated concomitantly discontinued (P < .001). Comparisons of 1 drug vs combination (2 to 4 drugs) and use for treating cancers that were FDA-approved indications vs off-label use were significant (P < .001), whereas comparisons of stage II or lower vs stage III and IV cancer and of those aged ≤ 50 years vs aged > 50 years were not significant (P = .50 and P = .30, respectively) (Table 4).

TABLE 4

Adverse Event-Related Discontinuationsa

| Criteria | Paclitaxel use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse events, No. | Patients, No. | Patients, % | P value | |

| Treatment | ||||

Alone Alone | 0 | 16 | 0 | < .001 |

Concomitant Concomitant | 364 | 686 | 53 | |

1 medication (alone, before, or after) 1 medication (alone, before, or after) | 55 | 75 | 73 | < .001 |

Combination (2 – 4 drugs) Combination (2 – 4 drugs) | 309 | 627 | 49 | |

|

| ||||

| Cancers | ||||

Food and Drug Administration-approved cancer indication Food and Drug Administration-approved cancer indication | 305 | 546 | 56 | < .001 |

Others (off-label) Others (off-label) | 59 | 156 | 38 | |

Stage 0, I, II, not applicable, or unknown Stage 0, I, II, not applicable, or unknown | 202 | 398 | 51 | .50 |

Stage III and IV Stage III and IV | 162 | 304 | 53 | |

|

| ||||

| Age | ||||

≤ 50 y ≤ 50 y | 123 | 225 | 55 | .30 |

> 50 y > 50 y | 241 | 477 | 51 | |

Among the 364 patients who had concomitant treatment and had discontinued their treatment, 332 (91%) switched treatments with no AEs documented and 32 (9%) experienced fatigue with pneumonia, mucositis, neuropathy, neurotoxicity, neutropenia, pneumonitis, allergic or hypersensitivity reaction, or an unknown AE. Patients who discontinued treatment because of unknown AEs had a physician’s note that detailed progressive disease, a significant decline in performance status, and another unknown adverse effect due to a previous sinus tract infection and infectious colitis (Table 5).

TABLE 5

Adverse Event-Related Discontinuations (N = 364)

| Adverse event | Alone, No. | Concomitant, No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse events | 0 | 32 (9) |

Fatigue and pneumonia Fatigue and pneumonia | — | 1 (< 1) |

Mucositis Mucositis | — | 1 (< 1) |

Neuropathy Neuropathy | — | 4 (1) |

Neurotoxicity Neurotoxicity | — | 1 (< 1) |

Neutropenia Neutropenia | — | 2 (1) |

Pneumonitis Pneumonitis | — | 3 (1) |

Reaction of allergic or hypersensitivity Reaction of allergic or hypersensitivity | — | 8 (2) |

Unknown Unknown | — | 12 (3) |

|

| ||

| No documentation | 0 | 332 (91) |

|

| ||

| Changed treatment | 0 | 332 (91) |

Management Analysis and Reporting Tool Database

MHS data analysts provided data on diagnoses for 639 patients among 687 submitted diagnoses, with 294 patients completing and 345 discontinuing paclitaxel treatment. Patients in the completed treatment group had 3 to 258 unique health conditions documented, while patients in the discontinued treatment group had 4 to 181 unique health conditions documented. The MHS reported 3808 unique diagnosis conditions for the completed group and 3714 for the discontinued group (P = .02).

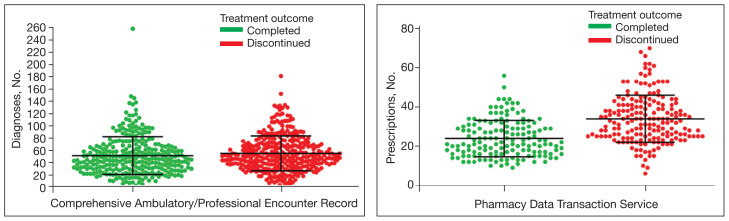

The mean (SD) number of diagnoses was 51 (31) for the completed and 55 (28) for the discontinued treatment groups (Figure). Among 639 patients who received paclitaxel, the top 5 diagnoses were administrative, including encounters for other administrative examinations; antineoplastic chemotherapy; administrative examination for unspecified; other specified counseling; and adjustment and management of vascular access device. The database does not differentiate between administrative and clinically significant diagnoses.

Diagnoses and Prescriptions for Patients Receiving Paclitaxel by Treatment Outcome

Mean and SD shown for each distribution; patients who discontinued treatment had more diagnosed medical issues compared with those who completed treatment; patients who took paclitaxel concomitantly with a greater number of prescription drugs had a higher rate of treatment discontinuation than those who received fewer filled prescriptions

MHS data analysts provided data for 336 of 687 submitted patients who were prescribed paclitaxel; 46 patients had no PDTS data, and 305 patients had PDTS data without paclitaxel, Taxol, or Abraxane dispensed. Medications that were filled outside the chemotherapy period were removed by evaluating the dispensed date and day of supply. Among these 336 patients, 151 completed the treatment and 185 discontinued, with 14 patients experiencing documented AEs. Patients in the completed treatment group filled 9 to 56 prescriptions while patients in the discontinued treatment group filled 6 to 70 prescriptions. Patients in the discontinued group filled more prescriptions than those who completed treatment: 793 vs 591, respectively (P = .34).

The mean (SD) number of filled prescription drugs was 24 (9) for the completed and 34 (12) for the discontinued treatment group. The 5 most filled prescriptions with paclitaxel from 336 patients with PDTS data were dexamethasone (324 prescriptions with 14 recorded AEs), diphenhydramine (296 prescriptions with 12 recorded AEs), ondansetron (277 prescriptions with 11 recorded AEs), prochlorperazine (265 prescriptions with 12 recorded AEs), and sodium chloride (232 prescriptions with 11 recorded AEs).

DISCUSSION

As a retrospective review, this study is more limited in the strength of its conclusions when compared to randomized control trials. The DoD Cancer Registry Program only contains information about cancer types, stages, treatment regimens, and physicians’ notes. Therefore, noncancer drugs are based solely on the PDTS database. In most cases, physicians’ notes on AEs were not detailed. There was no distinction between initial vs later lines of therapy and dosage reductions. The change in status or appearance of a new medical condition did not indicate whether paclitaxel caused the changes to develop or directly worsen a pre-existing condition. The PDTS records prescriptions filled, but that may not reflect patients taking prescriptions.

Paclitaxel

Paclitaxel has a long list of both approved and off-label uses in malignancies as a primary agent and in conjunction with other drugs. The FDA prescribing information for Taxol and Abraxane was last updated in April 2011 and September 2020, respectively.20,21 The National Institutes of Health National Library of Medicine has the current update for paclitaxel on July 2023.19,22 Thus, the prescribed information for paclitaxel referenced in the database may not always be up to date. The combinations of paclitaxel with bevacizumab, carboplatin, or carboplatin and pembrolizumab were not in the Taxol prescribing information. Likewise, a combination of nab-paclitaxel with atezolizumab or carboplatin and pembrolizumab is missing in the Abraxane prescribing information.22–27

The generic name is not the same as a generic drug, which may have slight differences from the brand name product.71 The generic drug versions of Taxol and Abraxane have been approved by the FDA as paclitaxel injectable and paclitaxel-protein bound, respectively. There was a global shortage of nab-paclitaxel from October 2021 to June 2022 because of a manufacturing problem.72 During this shortage, data showed similar comments from physician documents that treatment switched to Taxol due to the Abraxane shortage.

Of 336 patients in the PDTS database with dispensed paclitaxel prescriptions, 276 received paclitaxel (year dispensed, 2013–2022), 27 received Abraxane (year dispensed, 2013–2022), 47 received Taxol (year dispensed, 2004–2015), 8 received both Abraxane and paclitaxel, and 6 received both Taxol and paclitaxel. Based on this information, it appears that the distinction between the drugs was not made in the PDTS until after 2015, 10 years after Abraxane received FDA approval. Abraxane was prescribed in the MHS in 2013, 8 years after FDA approval. There were a few comparison studies of Abraxane and Taxol.73–76

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients have not been established for paclitaxel. According to the DoD Cancer Registry Program, the youngest patient was aged 2 months. In 2021, this patient was diagnosed with corpus uteri and treated with carboplatin and Taxol in course 1; in course 2, the patient reacted to Taxol; in course 3, Taxol was replaced with Abraxane; in courses 4 to 7, the patient was treated with carboplatin only.

Discontinued Treatment

Ten patients had prescribed Taxol that was changed due to AEs: 1 was switched to Abraxane and atezolizumab, 3 switched to Abraxane, 2 switched to docetaxel, 1 switched to doxorubicin, and 3 switched to pembrolizumab (based on physician’s comments). Of the 10 patients, 7 had Taxol reaction, 2 experienced disease progression, and 1 experienced high programmed death–ligand 1 expression (this patient with breast cancer was switched to Abraxane and atezolizumab during the accelerated FDA approval phase for atezolizumab, which was later revoked). Five patients were treated with carboplatin and Taxol for cancer of the anal canal (changed to pembrolizumab after disease progression), lung not otherwise specified (changed to carboplatin and pembrolizumab due to Taxol reaction), lower inner quadrant of the breast (changed to doxorubicin due to hypersensitivity reaction), corpus uteri (changed to Abraxane due to Taxol reaction), and ovary (changed to docetaxel due to Taxol reaction). Three patients were treated with doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and Taxol for breast cancer; 2 patients with breast cancer not otherwise specified switched to Abraxane due to cardiopulmonary hypersensitivity and Taxol reaction and 1 patient with cancer of the upper outer quadrant of the breast changed to docetaxel due to allergic reaction. One patient, who was treated with paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin for metastasis of the lower lobe of the lung and kidney cancer, experienced complications due to infectious colitis (treated with ciprofloxacin) and then switched to pembrolizumab after the disease progressed. These AEs are known in paclitaxel medical literature on paclitaxel AEs.19–24,77–81

Combining 2 or more treatments to target cancer-inducing or cell-sustaining pathways is a cornerstone of chemotherapy.82–84 Most combinations are given on the same day, but some are not. For 3- or 4-drug combinations, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide were given first, followed by paclitaxel with or without trastuzumab, carboplatin, or pembrolizumab. Only 16 patients (2%) were treated with paclitaxel alone; therefore, the completed and discontinued treatment groups are mostly concomitant treatment. As a result, the comparisons of the completed and discontinued treatment groups were almost the same for the diagnosis. The PDTS data have a better result because 2 exclusion criteria were applied before narrowing the analysis down to paclitaxel treatment specifically.

Antidepressants and Other Drugs

Drug response can vary from person to person and can lead to treatment failure related to AEs. One major factor in drug metabolism is CYP.85 CYP2C8 is the major pathway for paclitaxel and CYP3A4 is the minor pathway. When evaluating the noncancer drugs, there were no reports of CYP2C8 inhibition or induction. Over the years, many DDI warnings have been issued for paclitaxel with different drugs in various electronic resources.

Oncologists follow guidelines to prevent DDIs, as paclitaxel is known to have severe, moderate, and minor interactions with other drugs. Among 687 patients, 261 (38%) were prescribed any of 14 antidepressants. Eight of these antidepressants (amitriptyline, citalopram, desipramine, doxepin, venlafaxine, escitalopram, nortriptyline, and trazodone) are metabolized, 3 (mirtazapine, sertraline, and fluoxetine) are metabolized and inhibited, 2 (bupropion and duloxetine) are neither metabolized nor inhibited, and 1 (paroxetine) is inhibited by CYP3A4. Duloxetine, venlafaxine, and trazodone were more commonly dispensed (84, 78, and 42 patients, respectively) than others (≤ 33 patients).

Of 32 patients with documented AEs, 14 (44%) had 168 dispensed drugs in the PDTS database. Six patients (19%) were treated with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel for breast cancer; 6 (19%) were treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel for cancer of the lung (n = 3), corpus uteri (n = 2), and ovary (n = 1); 1 patient (3%) was treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel, then switched to carboplatin, bevacizumab, and paclitaxel, and then completed treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel for an unspecified female genital cancer; and 1 patient (3%) was treated with cisplatin, ifosfamide, and paclitaxel for metastasis of the lower lobe lung and kidney cancer.

The 14 patients with PDTS data had 18 cancer drugs dispensed. Eleven had moderate interaction reports and 7 had no interaction reports. A total of 165 noncancer drugs were dispensed, of which 3 were antidepressants and had no interactions reported, 8 had moderate interactions reported, and 2 had minor interactions with Taxol and Abraxane, respectively (Table 6).86–129

TABLE 6

Medications With Potential to Inhibit and Induce Effects on CYP P450 Isoenzymes and Metabolism Pathways Observed Among Patients Experiencing Adverse Events With Paclitaxel

| Type | Medication (No. prescriptions/No. AEs) | CYP inhibition/inducement | CYP metabolization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Paclitaxel (336/14) | Unknown/not reported | (2C8)a, 3A4 |

| Carboplatin (198/8)b,c | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Doxorubicin (116/6)b,c | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Cyclophosphamide (96/5)b,c | Unknown/not reported | 2B6, 3A4, 3A5, 2C9 | |

| Gemcitabine (16/1)b,c | Unknown/not reported | (3A4, 2B6)a, 2A6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19 | |

| Ifosfamide (4/1)b,c | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Cisplatin (20/1)b,c | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Bevacizumab (26/1)b | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Pembrolizumab (22/1)b | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Capecitabine (27/2)c | I nhibit: 2C9; uninhibited: 1A2, 2A6, 3A4, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1 | — | |

| Pemetrexed (8/1)c | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Topotecan (5/1)c | U ninhibited: 1A2, 2A6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E, 3A, 4A | 3A, 2A1 | |

| Palbociclib (4/1)c | I nhibit: 3A (weak); uninhibited: 1A2, 2A6, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6; uninduced: 1A2, 2B6, 2C8, 3A4 | 3A | |

| Vinorelbine (2/1)c | Unknown/not reported | 3A4, 2A6 | |

| Letrozole (20/2) | Inhibit: 2A6 (potent/strong), 2C19 (weak/mild) | ||

| Tamoxifen (22/1) | Unknown/not reported | (3A4/5, 2D6)a,1A2, 2B6, 2C9, 2C19 | |

| Anastrozole (45/1) | Inhibit: 1A2, 2C8/9, 3A4 (weak/mild); uninhibited: 2A6, 2D6 | — | |

| Megestrol (13/1) | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Durvalumab (7/1) | Unknown/not reported | — | |

|

| |||

| Antidepressant | Nortriptyline (3/2) | Unknown/not reported | (2D6)a, 1A2, 2C, 3A4 |

| Bupropion (11/1) | Inhibit: 2D6 | 2B6 | |

| Paroxetine (2/1) | Inhibit: 2D6 (potent/strong), 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 3A4 (weak/mild) | (2D6)a, 3A4, 2C9 | |

|

| |||

| Noncancer | Dexamethasone (324/14)c | Induce: 3A4 (weak/mild) | 3A4 |

| Pegfilgrastim (150/6)c | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Aprepitant (83/3)c | Unknown/not reported | (3A4)a, 1A2, 2C19 | |

| Atorvastatin (55/3)c | Uninhibited: 3A4 | 3A4 | |

| Ciprofloxacin (39/3)d | Inhibit: 1A2 | (1A2)a | |

| Cimetidine (28/2)c | Inhibit: 1A2, 2C9, 2D6, 3A4 | — | |

| Filgrastim (36/2)c | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Metronidazole (22/2)c | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Gatifloxacin (6/1)d | Uninhibited: 3A4, 2D6, 2C9, 2C19, 1A2 | — | |

| Nitrofurantoin (31/1)c | Unknown/not reported | — | |

| Losartan (11/1)c | Unknown/not reported | (2C9)a, 3A4 | |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse events; CYP, cytochrome P450.

Of 3 patients who were dispensed bupropion, nortriptyline, or paroxetine, 1 patient with breast cancer was treated with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, followed by paclitaxel with bupropion, nortriptyline, pegfilgrastim, dexamethasone, and 17 other noncancer drugs that had no interaction report dispensed during paclitaxel treatment. Of 2 patients with lung cancer, 1 patient was treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel with nortriptyline, dexamethasone, and 13 additional medications, and the second patient was treated with paroxetine, cimetidine, dexamethasone, and 12 other medications. Patients were dispensed up to 6 noncancer medications on the same day as paclitaxel administration to control the AEs, not including the prodrugs filled before the treatments. Paroxetine and cimetidine have weak inhibition, and dexamethasone has weak induction of CYP3A4. Therefore, while 1:1 DDIs might have little or no effect with weak inhibit/induce CYP3A4 drugs, 1:1:1 or more combinations could have a different outcome (confirmed in previous publications).65–67

Dispensed on the same day may not mean taken at the same time. One patient experienced an AE with dispensed 50 mg losartan, carboplatin plus paclitaxel, dexamethasone, and 6 other noncancer drugs. Losartan inhibits paclitaxel, which can lead to negative AEs.57,66,67 However, there were no blood or plasma samples taken to confirm the losartan was taken at the same time as the paclitaxel given this was not a clinical trial.

CONCLUSIONS

This retrospective study discusses the use of paclitaxel in the MHS and the potential DDIs associated with it. The study population consisted mostly of active-duty personnel, who are required to be healthy or have controlled or nonactive medical diagnoses and be physically fit. This group is mixed with dependents and retirees that are more reflective of the average US population. As a result, this patient population is healthier than the general population, with a lower prevalence of common illnesses such as diabetes and obesity. The study aimed to identify drugs used alongside paclitaxel treatment. While further research is needed to identify potential DDIs among patients who experienced AEs, in vitro testing will need to be conducted before confirming causality. The low number of AEs experienced by only 32 of 702 patients (5%), with no deaths during paclitaxel treatment, indicates that the drug is generally well tolerated. Although this study cannot conclude that concomitant use with noncancer drugs led to the discontinuation of paclitaxel, we can conclude that there seems to be no significant DDIs identified between paclitaxel and antidepressants. This comprehensive overview provides clinicians with a complete picture of paclitaxel use for 27 years (1996–2022), enabling them to make informed decisions about paclitaxel treatment.

Acknowledgments

The Department of Research Program funds at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center supported this protocol. We sincerely appreciate the contribution of data extraction from the Joint Pathology Center teams (Francisco J. Rentas, John D. McGeeney, Beatriz A. Hallo, and Johnny P. Beason) and the MHS database personnel (Maj Ryan Costantino, Brandon E. Jenkins, and Alexander G. Rittel). We gratefully thank you for the protocol support from the Department of Research programs: CDR Martin L. Boese, CDR Wesley R. Campbell, Maj. Abhimanyu Chandel, CDR Ling Ye, Chelsea N. Powers, Yaling Zhou, Elizabeth Schafer, Micah Stretch, Diane Beaner, and Adrienne Woodard.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the official position or policy of the Defense Health Agency, US Department of Defense, the US Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Ethics and consent: The study protocol was approved by the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Institutional Review Board and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act as an exempt protocol.

Author disclosures: The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest or outside sources of funding with regard to this article.

References

Articles from Federal Practitioner are provided here courtesy of Frontline Medical Communications

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Retrospective Evaluation of Drug-Drug Interactions With Erlotinib and Gefitinib Use in the Military Health System.

Fed Pract, 40(suppl 3):S24-S34, 15 Aug 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38021095 | PMCID: PMC10681012

Repaglinide : a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Pharmacoeconomics, 22(6):389-411, 01 Jan 2004

Cited by: 24 articles | PMID: 15099124

Review

Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2(2022), 01 Feb 2022

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 36321557 | PMCID: PMC8805585

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Results from a mailed promotion of medication reviews among Department of Defense beneficiaries receiving 10 or more chronic medications.

J Manag Care Pharm, 16(8):578-592, 01 Oct 2010

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 20866163 | PMCID: PMC10438093

a

a