Abstract

Free full text

A case of cytomegalovirus cystic lung disease and review of literature

Abstract

A 31‐week gestation male infant with respiratory distress since day of delivery had lobectomy at 8 weeks of age for symptomatic, suspected congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM). Histology of resected lung showed cytomegalovirus (CMV) inclusion bodies and emphysematous changes. The infant was treated with antiviral therapy with improvement in symptoms. CMV infection of the lung should be considered in any neonate presenting with lung cysts.

weeks of age for symptomatic, suspected congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM). Histology of resected lung showed cytomegalovirus (CMV) inclusion bodies and emphysematous changes. The infant was treated with antiviral therapy with improvement in symptoms. CMV infection of the lung should be considered in any neonate presenting with lung cysts.

Abstract

A preterm infant with respiratory distress since day of delivery had lobectomy at 8 weeks of age for symptomatic, suspected congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM). Histology of resected lung showed cytomegalovirus (CMV) inclusion bodies and emphysematous changes.

weeks of age for symptomatic, suspected congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM). Histology of resected lung showed cytomegalovirus (CMV) inclusion bodies and emphysematous changes.

INTRODUCTION

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is the commonest infection among newborns worldwide. 1 CMV pneumonitis is well‐described among infants, especially immunocompromised and preterm babies. CMV‐associated lung cysts are comparatively less well described. We report a case of a preterm baby with respiratory distress and a preoperative diagnosis of suspected congenital pulmonary airway malformation, who had a lobectomy, and a post‐operative diagnosis of CMV lung infection. We further review the literature of CMV‐associated lung cysts.

CASE REPORT

A male preterm infant, born at 31 weeks gestation, via spontaneous vaginal delivery following prolonged premature rupture of membranes, was referred to the pulmonology unit of a tertiary facility at age 6

weeks gestation, via spontaneous vaginal delivery following prolonged premature rupture of membranes, was referred to the pulmonology unit of a tertiary facility at age 6 weeks post‐delivery, on account of prolonged respiratory distress requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) ventilation. His birthweight was 1300

weeks post‐delivery, on account of prolonged respiratory distress requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) ventilation. His birthweight was 1300 g and Apgar scores were 6/10 and 8/10 at 1 and 5

g and Apgar scores were 6/10 and 8/10 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. The infant did not need resuscitation after birth. The mother was HIV‐positive on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), with suppressed HIV viral load of less than 50 copies per ml at the time of delivery. A late obstetric ultrasound scan done at 31

minutes, respectively. The infant did not need resuscitation after birth. The mother was HIV‐positive on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), with suppressed HIV viral load of less than 50 copies per ml at the time of delivery. A late obstetric ultrasound scan done at 31 weeks gestation diagnosed a twin pregnancy with no suggestion of a congenital thoracic malformation. The mother received a dose of betamethasone and two doses of oral azithromycin prophylaxis prior to delivery. The infant was the first of a monochorionic, diamniotic set of twins. He was administered nevirapine prophylaxis for 6

weeks gestation diagnosed a twin pregnancy with no suggestion of a congenital thoracic malformation. The mother received a dose of betamethasone and two doses of oral azithromycin prophylaxis prior to delivery. The infant was the first of a monochorionic, diamniotic set of twins. He was administered nevirapine prophylaxis for 6 weeks for the prevention of perinatal HIV acquisition. Birth HIV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was negative. He was breastfed for 21

weeks for the prevention of perinatal HIV acquisition. Birth HIV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was negative. He was breastfed for 21 days after which formula supplementation was started because of low maternal milk supply. The infant was exclusively formula‐fed at the time of admission to our tertiary facility.

days after which formula supplementation was started because of low maternal milk supply. The infant was exclusively formula‐fed at the time of admission to our tertiary facility.

A few hours after delivery, the infant developed respiratory distress which was attributed to respiratory distress syndrome and received a single dose of surfactant. Intravenous (IV) antibiotics were commenced for presumed sepsis but discontinued after 3 days when blood culture had no growth and c‐reactive protein (CRP) was 1

days when blood culture had no growth and c‐reactive protein (CRP) was 1 mg/L. Echocardiogram was normal. Brain ultrasound showed a structurally normal preterm brain with grade

mg/L. Echocardiogram was normal. Brain ultrasound showed a structurally normal preterm brain with grade −

− 1 left intraventricular haemorrhage, bilateral periventricular white matter flaring, and no ventriculomegaly or brain calcifications. No investigations for CMV were done for the infant or mother at this stage as CMV was not suspected.

1 left intraventricular haemorrhage, bilateral periventricular white matter flaring, and no ventriculomegaly or brain calcifications. No investigations for CMV were done for the infant or mother at this stage as CMV was not suspected.

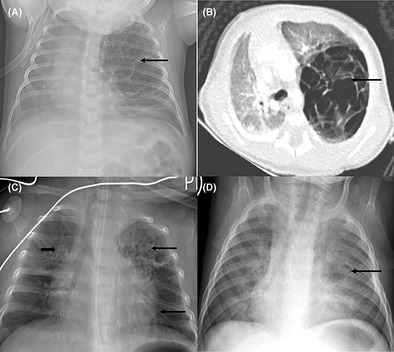

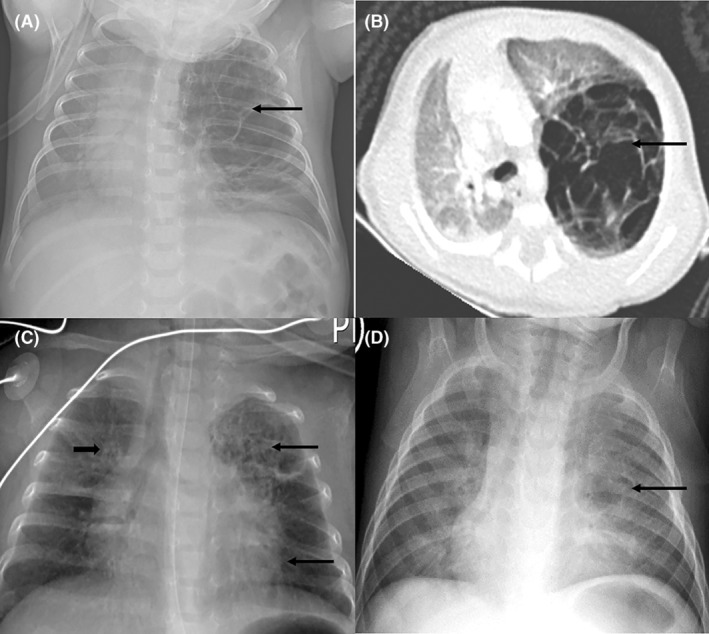

The respiratory distress improved gradually and then worsened at age 5 weeks. Chest x‐ray done at this stage demonstrated a large multilocular cystic mass in the left upper zone suggestive of a congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM), Figure 1A. There had been no previous chest x‐rays taken. The infant was subsequently referred to the pulmonology unit of our tertiary facility.

weeks. Chest x‐ray done at this stage demonstrated a large multilocular cystic mass in the left upper zone suggestive of a congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM), Figure 1A. There had been no previous chest x‐rays taken. The infant was subsequently referred to the pulmonology unit of our tertiary facility.

Pre‐operative and post‐operative chest x‐rays and computed tomography (CT) scan of a preterm baby with a pre‐operative diagnosis of suspected congenital pulmonary airway malformation. 1a: Chest x‐ray showing a large multilocular cystic mass in the left upper lobe(arrow), with shift of the mediastinum to the right; 1b: Chest CT scan (axial view) showing an expansile multilocular cystic mass arising from the left upper lobe (arrow), with shift of the mediastinum to the right, and compression of the right lung; 1c: Chest x‐ray after left upper lobectomy and 2 weeks of IV ganciclovir, showing resolution of mediastinal shift, right sided linear opacities (short arrow), and left sided cystic lesions in the expanded left lower and remainder of upper lobes (long arrows); 1d: Chest x‐ray after 6

weeks of IV ganciclovir, showing resolution of mediastinal shift, right sided linear opacities (short arrow), and left sided cystic lesions in the expanded left lower and remainder of upper lobes (long arrows); 1d: Chest x‐ray after 6 weeks of antiviral therapy showing bilateral patchy opacification and a single cyst of the left lingula area (arrow).

weeks of antiviral therapy showing bilateral patchy opacification and a single cyst of the left lingula area (arrow).

Examination findings on arrival to the pulmonology unit were tachypnoea with chest indrawing, decreased air entry of the left hemithorax, and requirement of nasal cannula oxygen at 2 L/min to maintain normal oxygen saturations. There were no dysmorphic features or microcephaly. Abdominal, skin, cardiovascular and neurological examinations were normal. A chest CT scan showed an expansile multilocular cystic mass arising from the left upper lobe with no associated aberrant arterial supply to suggest a hybrid lesion, Figure 1B. This lesion exerted mass effect on the mediastinum and right lung. A left upper lobectomy at a postnatal age of 8

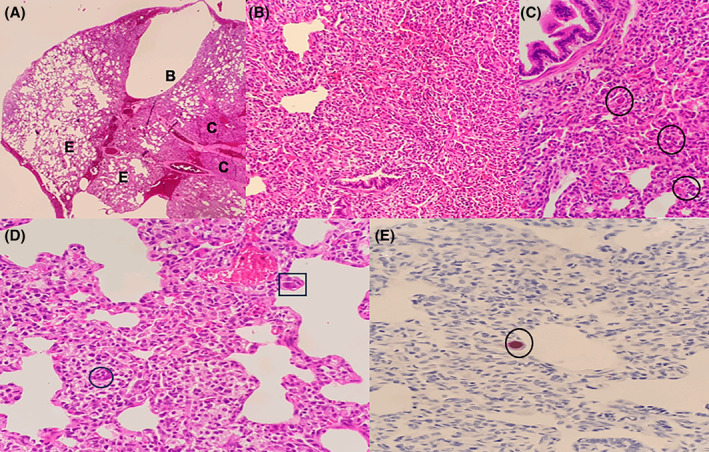

L/min to maintain normal oxygen saturations. There were no dysmorphic features or microcephaly. Abdominal, skin, cardiovascular and neurological examinations were normal. A chest CT scan showed an expansile multilocular cystic mass arising from the left upper lobe with no associated aberrant arterial supply to suggest a hybrid lesion, Figure 1B. This lesion exerted mass effect on the mediastinum and right lung. A left upper lobectomy at a postnatal age of 8 weeks was performed on the assumption that this was a symptomatic CPAM. Post‐operative chest x‐ray demonstrated some residual cystic changes of the left lung, Figure 1C. Histology of resected lung had features consistent with CMV infection with no evidence of CPAM, Figure 2.

weeks was performed on the assumption that this was a symptomatic CPAM. Post‐operative chest x‐ray demonstrated some residual cystic changes of the left lung, Figure 1C. Histology of resected lung had features consistent with CMV infection with no evidence of CPAM, Figure 2.

Histology of resected lung showing emphysematous changes and cytomegalovirus inclusion bodies. (A) is a low power view, showing lung tissue with a subpleural bulla [B], areas of emphysematous change [E] and patchy consolidation [C]. High power view of these areas in (B) shows interstitial expansion by chronic inflammation with scattered large cells seen (C, circle) (D) is a high power view showing an endothelial cell (square) and pneumocyte (circle) containing nuclear and cytoplasmic viral inclusions. (A–D) were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. (E) shows the cytomegalovirus immunohistochemical stain which highlights the nuclear viral inclusion.

Blood CMV viral load was log 5.2 (146,328 IU/mL). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of CMV‐lung disease was considered, and intravenous ganciclovir was started. Serial full blood counts did not show any lymphopenia or thrombocytopenia, liver function tests were normal, eye examination and hearing screen were also normal. The infant gained weight well, the respiratory distress resolved, and he was discharged after 2

IU/mL). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of CMV‐lung disease was considered, and intravenous ganciclovir was started. Serial full blood counts did not show any lymphopenia or thrombocytopenia, liver function tests were normal, eye examination and hearing screen were also normal. The infant gained weight well, the respiratory distress resolved, and he was discharged after 2 weeks of IV ganciclovir to complete a 4‐week course of oral valganciclovir. Repeat CMV viral load after 2

weeks of IV ganciclovir to complete a 4‐week course of oral valganciclovir. Repeat CMV viral load after 2 weeks therapy decreased to log 3.4 (2489

weeks therapy decreased to log 3.4 (2489 IU/mL).

IU/mL).

On follow up 6 weeks after lobectomy, the infant had no respiratory distress and chest examination was normal. Repeat chest x‐ray showed a persistent cystic lesion of the left lung as well as bilateral opacities, Figure 1D. His immune workup had high immunoglobulin M, cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells, suggestive of an ongoing infection. CMV viral load was now 9673

weeks after lobectomy, the infant had no respiratory distress and chest examination was normal. Repeat chest x‐ray showed a persistent cystic lesion of the left lung as well as bilateral opacities, Figure 1D. His immune workup had high immunoglobulin M, cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells, suggestive of an ongoing infection. CMV viral load was now 9673 IU/mL (log 4), thus the duration of treatment with oral valganciclovir was extended. The twin had normal examination findings and an undetectable CMV viral load.

IU/mL (log 4), thus the duration of treatment with oral valganciclovir was extended. The twin had normal examination findings and an undetectable CMV viral load.

DISCUSSION

This case of a preterm infant highlights an unusual manifestation of perinatally acquired CMV‐associated lung disease which was mistaken for a CPAM. A few case reports have described cystic lung lesions associated with neonatal or congenital CMV infection. These are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1

Clinical and radiological characteristics of reported cases of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection among neonates associated with cystic lung lesions.

| Author and country | Antenatal ultrasonography (USG)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | Gestational age, birthweight | Mother's CMV test results | Baby's CMV test results | Chest x‐ray (CXR)/computed tomography (CT) | Antiviral therapy | Surgery | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carrol et al., 2 1996, UK | Polyhydramnios, fetal left upper lobe lesion at 29 weeks gestation weeks gestation | 32 weeks, 2000 weeks, 2000 g g | Serum CMV IgM positive | Urine culture CMV positive | Left upper lobe emphysema | Not stated | Left upper lobectomy. CMV inclusion bodies in resected lung | Discharged at 8 weeks of age weeks of age |

| Bradshaw and Moore, 3 2003, New Zealand | Normal antenatal USG | 30 weeks, 1590 weeks, 1590 g g |

Hepatitis at 28 Convalescing CMV IgM positive, CMV IgG positive. |

Day 1: CMV IgM negative, urine CMV negative Day 29: CMV IgM positive, IgG equivocal, Urine CMV positive |

Initial CXR: consistent with respiratory distress syndrome. Day 19: Cystic changes, right sided consolidation on CXR Day 29: worsened bilateral cystic changes on CXR Chest CT scan: multiple cystic changes | Not given | No surgery |

Day 43: partial resolution on CXR 16 |

| Cho et al., 4 2003, Turkey | Not stated | 38 weeks, 2450 weeks, 2450 g g | Not stated |

CMV IgM positive Urine CMV positive |

CXR on admission: right upper lobe pneumonia Chest CT scan 7 | Not stated |

Right upper lobe posterior segmentectomy CMV inclusion bodies in resected lung | CXR 1 month post discharge: no lesions month post discharge: no lesions |

| Staunton et al., 5 2012, UK | Polyhydramnios | 26 weeks, 965 weeks, 965 g g | CMV IgM and IgG positive | Day 1 of life: Urine CMV PCR positive, Blood CMV IgM positive, IgG negative. CMV viral load 151,000 copies/ml |

Initial CXR: respiratory distress syndrome pattern Day 51: left upper lobe emphysema with mediastinal shift | Oral vanganciclovir | Surgery on Day 52 of life. Emphysematous left upper lobe, CMV inclusion bodies in resected lung | Discharged on Day 89 |

| Kumar and Santhanam, 6 2015, India | Not stated | 31 weeks, 1060 weeks, 1060 g g | Not tested |

Urine CMV PCR positive Serum CMV IgM positive |

Initial CXR: normal. Later CXRs: evolution from left lung consolidation to left lung cysts | No antiviral therapy | No surgery | Complete resolution on CXR at 9 months months |

| Özdemir et al., 7 2020, Turkey | Normal fetal MRI | 35 weeks, 1870 weeks, 1870 g g | CMV IgM negative during pregnancy | CMV IgM positive |

Initial CXR: normal. Day 20: cystic lesion left lung zone, chest CT scan: multiple left lower lobe cysts | Intravenous ganciclovir | No surgery | Day 35 CXR: No cysts |

All the cases listed were neonates, and five of six were preterm babies. All the cases had evidence of CMV infection in blood, urine and/or resected lung specimen. One had evidence of a lung lesion antenatally, 2 while another had evidence of symptomatic maternal antenatal CMV infection. 3 Two cases were associated with polyhydramnios. 2 , 5 Four cases had cysts located in the left lung. 2 , 5 , 6 , 7 One case had bilateral cysts 3 and one had right lung cysts. 4

As in the other reported cases, our patient presented with respiratory distress, which was initially attributed to respiratory distress syndrome or neonatal sepsis. Our patient's mother was not diagnosed with polyhydramnios during pregnancy, as in some of the other reported cases. 2 , 5 She also did not report any illness during pregnancy, which would have heightened the suspicion for an intrauterine infection in our patient. Our patient had left lung cysts, which are commoner in neonatal CMV infections than right‐sided or bilateral cysts. 2 , 5 , 6 , 7 CMV inclusion bodies were found on the resected lung of our patient, similar to the reported cases of CMV‐associated cystic lung lesions that had resection. 2 , 4 , 5

Our patient's presumptive diagnosis of CPAM was based on his clinical and radiological findings. Although the antenatal ultrasound scan did not detect a congenital thoracic malformation, exclusion of a CPAM could not have been made with absolute certainty. The evidence in favour of CMV infection includes our patient's prematurity, similar to previously reported cases cited above. There was also no evidence of CPAM on histology of resected lung. However, it is difficult to determine when and how CMV was acquired in our patient as this baby was not tested at birth, and neither was the mother, as testing for CMV is not routine in our setting. As our patient did not have a chest x‐ray before the postnatal age of 6 weeks, there is also uncertainty about when these cystic lung lesions first developed.

weeks, there is also uncertainty about when these cystic lung lesions first developed.

CPAM associated with CMV co‐infection has been reported. 8 , 9 However, in our case, histology showed no features of a congenital lung lesion. As in our patient, differential CMV infection in twins has also been reported, with no clear explanation for this occurrence. 10

There is currently no consensus on the treatment of CMV‐associated cystic lung disease. Our decision to treat the baby post‐thoracotomy was based on the finding that the re‐expanded left lower lobe after upper lobe resection also showed cyst‐like changes on chest x‐ray, Figure 1C. CMV‐associated lung cysts have resolved with supportive management alone. 3 However, untreated CMV in preterm infants may lead to severe neurodevelopmental sequelae. 1 Additionally, data of long‐term lung health after CMV lung infection are lacking. Therefore, follow‐up of these patients until lung function testing can be done is worth considering.

CMV‐associated cystic lung disease in preterm babies may cause significant morbidity and is an important differential diagnosis for CPAM. Unusual presentations of congenital infections must be considered and tested for in preterm babies with cystic lung lesions as it could lead to avoidance of unnecessary surgical resection. Long‐term prognosis of CMV‐associated cystic lung disease requires further study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data, conception, initial and final drafts of this manuscript. Seyram M. Wordui, Marco Zampoli, Aneesa Vanker, Diane Gray reviewed the literature.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors declare that appropriate written informed consent was obtained for the publication of this manuscript and accompanying images.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank members of the multidisciplinary team that was involved in the management of this patient.

Notes

Wordui SM, Singh S, Pillay T, Zampoli M, Daniels A, Brooks A, et al. A case of cytomegalovirus cystic lung disease and review of literature. Respirology Case Reports. 2024;12(10):e70054. 10.1002/rcr2.70054 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Associate Editor: Daniel Ng

REFERENCES

Articles from Respirology Case Reports are provided here courtesy of Wiley

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Early resection of a rare congenital pulmonary airway malformation causing severe progressive respiratory distress in a preterm neonate: a case report and review of the literature.

BMC Pediatr, 23(1):238, 13 May 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37173730 | PMCID: PMC10182594

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Congenital cytomegalovirus infection associated with development of neonatal emphysematous lung disease.

BMJ Case Rep, 2012:bcr0220125737, 08 May 2012

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 22605840 | PMCID: PMC3351638

Spontaneous pneumothorax in a teenager with prior congenital pulmonary airway malformation.

Respir Med Case Rep, 11:18-21, 28 Feb 2014

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 26029523 | PMCID: PMC3969605

Case of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung associated with congenital pulmonary airway malformation in a neonate.

Korean J Pediatr, 61(1):30-34, 22 Jan 2018

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 29441110 | PMCID: PMC5807988

1

1