Abstract

Free full text

Use of short single-balloon enteroscopy in patients with surgically altered anatomy: a single-center experience

Abstract

Conventional duodenoscopy is challenging to perform in patients with a surgically altered anatomy (SAA). Short single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE) is an innovative alternative. We investigated the performance of short SBE in patients with SAA and explored risk factors for unsuccessful intubation. Patients who underwent short SBE from October 2019 to October 2023 were retrospectively analyzed. Successful enteroscopic intubation was defined as the endoscope reaching the papilla of Vater, the pancreaticobiliary-enteric anastomosis, or the target site of the afferent limb. In total, 99 short SBE procedures were performed in 64 patients (40 men, 24 women) with a mean age of 61 years (range, 36–86 years). The patients had a history of choledochoduodenostomy (n =

= 1), Billroth II gastrojejunostomy (n

1), Billroth II gastrojejunostomy (n =

= 11), pancreaticoduodenectomy (n

11), pancreaticoduodenectomy (n =

= 17), Roux-en-Y reconstruction with hepaticojejunostomy (n

17), Roux-en-Y reconstruction with hepaticojejunostomy (n =

= 31), and Roux-en-Y reconstruction with total gastrectomy (n

31), and Roux-en-Y reconstruction with total gastrectomy (n =

= 4). Successful enteroscopic intubation occurred in 32 of 64 (50.0%) patients, and in 57 of 99 (57.6%) procedures. No perforation or severe pancreatitis occurred. Multivariable analysis showed that Roux-en-Y reconstruction was a risk factor for intubation failure (hazard ratio, 4.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.1–15.8; p

4). Successful enteroscopic intubation occurred in 32 of 64 (50.0%) patients, and in 57 of 99 (57.6%) procedures. No perforation or severe pancreatitis occurred. Multivariable analysis showed that Roux-en-Y reconstruction was a risk factor for intubation failure (hazard ratio, 4.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.1–15.8; p =

= 0.033). Short SBE is efficacious and safe in patients with postsurgical anatomy. Roux-en-Y reconstruction adversely affects the success of short SBE intubation.

0.033). Short SBE is efficacious and safe in patients with postsurgical anatomy. Roux-en-Y reconstruction adversely affects the success of short SBE intubation.

Introduction

Conventional duodenoscopy is considered the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of many biliopancreatic diseases, and its success rate is approximately 95% in patients with normal gastrointestinal anatomy1. However, successful intubation in patients with a surgically altered anatomy (SAA) is technically difficult because of a long, angulated afferent limb and adhesions2–4. Therefore, in the past, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTCD) or surgical intervention was often done for postoperative biliary adverse events like cholangitis and choledochojejunostomy stricture5.

Balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE), encompassing double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE), single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE) and spiral enteroscopy (SE), is an effective technique for deep insertion of the small bowel5,6. The first BAE was successfully performed in 2005 by Haruta et al. in a patient with Roux-en-Y gastrectomy6. Subsequently, many studies have reported this procedure to be useful in patients with a surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy7–14.

SBE has recently been playing an increasingly important role in this regard15,16, particularly in the performance of short SBE17. The scope used for short SBE, which has a working length of 152 cm and a working channel diameter of 3.2 mm, is more compatible with conventional accessories for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Moreover, short SBE permits passive bending and high-force transmission, allowing the scope to smoothly advance and facilitating the efficient performance of torque operations18. However, short SBE and short SBE-assisted ERCP are technically demanding, and the success rate widely varies. We herein report our experience in performing short SBE and short SBE-assisted ERCP in a consecutive cohort of patients with SAA. We also explore the risk factors related to unsuccessful intubation.

Patients and methods

Patients

This single-center study was conducted at Shulan (Hangzhou) Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang Shuren University and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The present study received approval from the ethics committee of Shulan (Hangzhou) Hospital. Written informed consent to perform diagnosis and therapy by short SBE was obtained from all patients. We retrospectively reviewed consecutive patients with SAA who had undergone short SBE and short SBE-assisted ERCP from October 2019 to October 2023. In total, 99 procedures were performed in 64 patients aged ≥

≥ 18 years.

18 years.

Endoscopic procedures

Both aspirin and P2Y12 platelet inhibitors were prohibited during the short SBE procedure. Perioperative antibiotics were allowed for patients with cholangitis. The patients fasted for at least 6 h prior to the short SBE procedure. Bowel cleansing prior to short SBE procedure was not routine. They were placed in the prone position and monitored during anesthesia. A soft pillow was placed under the right chest wall to facilitate opening of the airway. A nasal oxygen tube was used for oxygen inhalation, and the oxygen flow rate was adjusted according to the patient’s clinical status. The patient underwent continuous monitoring of the oxygen saturation, electrocardiogram, and pulse rate and intermittent measurement of blood pressure. Carbon dioxide insufflation was used in all cases. All endoscopic procedures were performed by an experience endoscopist (performance of SBE >

> 30 cases per year) under fluoroscopic control. The enteroscope used in all cases was the SIF-H290S (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan), which has a 152 cm working length and a 3.2 mm working channel diameter. The specifications of the short SBE are detailed in a previous report18. A single-use overtube (ST-SB1S; Olympus Medical Systems, Japan) was used with the enteroscope in some patients. The balloon was remotely controlled by a balloon control unit (OBCU; Olympus Medical Systems, Japan). In some procedures, especially for patient with an intact papilla, a transparent cap (D-201–10704; Olympus Medical Systems, Japan) was attached to the tip of the enteroscope. The standard “push and pull” technique was used for SBE19. For difficult cases, the patient was shifted to the left lateral decubitus position or external abdominal pressure was applied18.

30 cases per year) under fluoroscopic control. The enteroscope used in all cases was the SIF-H290S (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan), which has a 152 cm working length and a 3.2 mm working channel diameter. The specifications of the short SBE are detailed in a previous report18. A single-use overtube (ST-SB1S; Olympus Medical Systems, Japan) was used with the enteroscope in some patients. The balloon was remotely controlled by a balloon control unit (OBCU; Olympus Medical Systems, Japan). In some procedures, especially for patient with an intact papilla, a transparent cap (D-201–10704; Olympus Medical Systems, Japan) was attached to the tip of the enteroscope. The standard “push and pull” technique was used for SBE19. For difficult cases, the patient was shifted to the left lateral decubitus position or external abdominal pressure was applied18.

Bile duct stones were removed with a retrieval balloon (TXR-8.5-12-15 A, COOK, United States)/(Extractor™ Pro XL, Boston Scientific, United States) or a basket (MWB-2 ×

× 4, COOK, United States) after balloon dilatation (BDC-8/55, 10/55, 12/55, Nanwei Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) according to the diameter of bile duct and the size of the stones.

4, COOK, United States) after balloon dilatation (BDC-8/55, 10/55, 12/55, Nanwei Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) according to the diameter of bile duct and the size of the stones.

The single-operator cholangioscopy system used in this study was the EyeMax system (Nanwei Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China), a novel fiber optic direct vision system. Biliary fully covered self-expandable metallic stent used in this study was EVO-FC-10-11-6-B or EVO-FC-10-11-8-B (6–8 cm length, COOK, United States). Intestinal self-expandable metallic stent used in this study was EVO-22-27-6-D (6 cm length, COOK, United States).

Patients after enteroscopy were followed up. Blood routine, coagulation function, and liver function tests were done regularly. Pay attention to the signs of peritonitis and be alert to post-SBE pancreatitis. According to the patients’ condition, if initial intubation failed, we tried SBE again (n =

= 7), or tried PTCD (n

7), or tried PTCD (n =

= 12), or surgical intervention (n

12), or surgical intervention (n =

= 5), or conservative treatment (n

5), or conservative treatment (n =

= 8) in our center. During the follow-up period, a total of 32 patients died, of which 17 occurred in the failed endoscopic intubation group.

8) in our center. During the follow-up period, a total of 32 patients died, of which 17 occurred in the failed endoscopic intubation group.

Definitions and outcome measurements

The primary outcome was to obtain the rate of technical success of enteroscopic intubation and to identify patient related risk factors associated with failed intubation.

Successful enteroscopic intubation was defined as the endoscope reaching the papilla of Vater, the pancreaticobiliary-enteric anastomosis, or the target site of the afferent limb. Procedural success was defined as successful completion of the entire procedure, from endoscope insertion to the intended treatment17. The enteroscopic intubation time was measured from insertion of the enteroscope through the mouth to arrival at the papilla of Vater, the pancreaticobiliary-enteric anastomosis, or the target site of the afferent limb. Endoscopic complications were defined in accordance with a previous report20.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are reported as frequency with proportion and were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, whereas continuous variables are reported as standard deviation (or median with interquartile range) and were compared using the independent Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test. Risk factors for unsuccessful intubation were identified using binary logistic regression analyses. “Enter” methodology was used in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Statistical significance was set at p <

< 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS for Windows, version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS for Windows, version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

In total, 99 short SBE procedures were performed in 64 patients (40 men, 24 women) with a mean age of 61 years (range, 36–86 years). The patients’ demographic characteristics, etiology of SAA, reconstruction method, enteroscopic intubation time, and clinical data are summarized in Table 1. All patients underwent prior surgical interventions: choledochoduodenostomy (n =

= 1), Billroth II gastrojejunostomy (n

1), Billroth II gastrojejunostomy (n =

= 11), pancreaticoduodenectomy (n

11), pancreaticoduodenectomy (n =

= 17), Roux-en-Y reconstruction with hepaticojejunostomy (n

17), Roux-en-Y reconstruction with hepaticojejunostomy (n =

= 31), and Roux-en-Y reconstruction with total gastrectomy (n

31), and Roux-en-Y reconstruction with total gastrectomy (n =

= 4). The indications for treatment were malignant biliary obstruction in 41 (41.4%) procedures, bile duct stones and cholangitis in 35 (35.4%), malignant afferent loop obstruction in 8 (8.1%), benign biliary stricture post liver transplantation in 4 (4.0%), recurrent tumor invasion of the duodenal stump after Billroth II gastrojejunostomy in 2 (2.0%), hemobilia in 2 (2.0%), bile leakage post pancreaticoduodenectomy in 2 (2.0%), pancreatitis attack after Billroth II gastrojejunostomy in 2 (2.0%), benign pancreatic stricture post pancreaticoduodenectomy in 2 (2.0%), and benign afferent loop obstruction post pancreaticoduodenectomy in 1 (1.0%). Enteroscopy was successful in 32 of 64 (50.0%) patients, and in 57 of 99 (57.6%) procedures (Table 2). The success rate of short SBE intubation in patients with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (34.0% [16/47]) was significantly lower than that in patients undergoing choledochoduodenostomy (100% [2/2]), Billroth II anastomosis (81% [17/21]), and pancreaticoduodenectomy (75.9% [22/29]) (p

4). The indications for treatment were malignant biliary obstruction in 41 (41.4%) procedures, bile duct stones and cholangitis in 35 (35.4%), malignant afferent loop obstruction in 8 (8.1%), benign biliary stricture post liver transplantation in 4 (4.0%), recurrent tumor invasion of the duodenal stump after Billroth II gastrojejunostomy in 2 (2.0%), hemobilia in 2 (2.0%), bile leakage post pancreaticoduodenectomy in 2 (2.0%), pancreatitis attack after Billroth II gastrojejunostomy in 2 (2.0%), benign pancreatic stricture post pancreaticoduodenectomy in 2 (2.0%), and benign afferent loop obstruction post pancreaticoduodenectomy in 1 (1.0%). Enteroscopy was successful in 32 of 64 (50.0%) patients, and in 57 of 99 (57.6%) procedures (Table 2). The success rate of short SBE intubation in patients with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (34.0% [16/47]) was significantly lower than that in patients undergoing choledochoduodenostomy (100% [2/2]), Billroth II anastomosis (81% [17/21]), and pancreaticoduodenectomy (75.9% [22/29]) (p <

< 0.05). The enteroscopic intubation time was significantly shorter in the successful intubation group than in the failed intubation group (35 vs. 79 min, respectively; p

0.05). The enteroscopic intubation time was significantly shorter in the successful intubation group than in the failed intubation group (35 vs. 79 min, respectively; p <

< 0.05).

0.05).

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of the patients.

| Variable | SAA patients underwent short SBE |

|---|---|

Age, years, mean ± ± SD SD | 61.0 ± ± 11.6 11.6 |

BMI, kg/m2, mean ± ± SD SD | 20.6 ± ± 2.9 2.9 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 40 (62.5%) |

| Female | 24 (37.5%) |

| Etiology for SAA, n (%) | |

| Benign | 15 (23.4%) |

| Malignant | 49 (76.6%) |

| Reconstruction method, n (%) | |

| Choledochoduodenostomy | 1 (1.6%) |

| Billroth II gastrojejunostomy | 11 (17.2%) |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 17 (26.6%) |

| Roux-en-Y with total gastrectomy | 4 (6.3%) |

| Roux-en-Y with hepaticojejunostomy | 31 (48.4%) |

| Indication for procedures, n (%) | n = = 99 99 |

| Malignant biliary obstruction | 41 (41.4%) |

| Bile duct stones and cholangitis | 35 (35.4%) |

| Malignant afferent loop obstruction | 8 (8.1%), |

Benign biliary stricture post liver transplantation | 4 (4.0%) |

| Recurrent tumor invasion of the duodenal stump after Billroth II gastrojejunostomy | 2 (2.0%) |

| Hemobilia | 2 (2.0%) |

| Bile leakage post pancreaticoduodenectomy | 2 (2.0%) |

| Pancreatitis attack post Billroth II gastrojejunostomy | 2 (2.0%) |

Benign pancreatic stricture post pancreaticoduodenectomy | 2 (2.0%) |

| Benign afferent loop obstruction post pancreaticoduodenectomy | 1 (1.0%) |

SAA: surgically altered anatomy; SBE: single-balloon enteroscopy; SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index.

Table 2

Successful and unsuccessful short SBE intubation.

| Variable | Successful intubation (n  = = 57) 57) | Unsuccessful intubation (n  = = 42) 42) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

Age, years, mean ± ± SD SD | 61.0 ± ± 11.4 11.4 | 60.9 ± ± 12.1 12.1 | 0.946 |

BMI, kg/m2, mean ± ± SD SD | 20.6 ± ± 2.7 2.7 | 20.7 ± ± 3.2 3.2 | 0.878 |

| Reconstruction method | 0.001 | ||

| Choledochoduodenostomy | 2 | 0 | / |

| Billroth II gastrojejunostomy | 17 | 4 | / |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 22 | 7 | / |

| Roux-en-Y with total gastrectomy | 0 | 4 | / |

| Roux-en-Y with hepaticojejunostomy | 16 | 27 | / |

| History of gastrectomy | 44 | 15 | 0.001 |

| History of heptectomy | 32 | 26 | 0.565 |

| Overtube | 26 | 23 | 0.368 |

| Transparent cap | 28 | 25 | 0.305 |

ERCP preoperative albumin, g/L, mean ± ± SD SD | 34.5 ± ± 5.9 5.9 | 34.2 ± ± 5.9 5.9 | 0.819 |

| ERCP preoperative TB, µmol/L, median (IQR) | 37.0 (50.0) | 31.0 (135.3) | 0.697 |

| ERCP preoperative DB, µmol/L, median (IQR) | 21.0 (41.5) | 19.5 (104.8) | 0.681 |

| ERCP preoperative GGT, U/L, median (IQR) | 223.0 (394.5) | 184.0 (387.5) | 0.513 |

| ERCP preoperative AKP, U/L, median (IQR) | 279.0 (490.0) | 239.0 (350.5) | 0.322 |

| ERCP preoperative ALT, U/L, median (IQR) | 41.0 (49.0) | 48.5 (74.0) | 0.501 |

| ERCP preoperative AST, U/L, median (IQR) | 45.0 (65.5) | 55.5 (54.8) | 0.533 |

| Enteroscopic intubation time, minutes, median (IQR) | 35.0 (48.0) | 79.0 (80.0) | 0.001 |

SBE: single-balloon enteroscopy; SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; IQR: interquartile range; TB: total bilirubin; DB: direct bilirubin; GGT: γ-glutamyltranspeptidase; AKP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase;

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Generally, duodenoscopy, and gastroscopy allow for successful endoscopic diagnosis and treatment in patients who undergo choledochoduodenostomy. However, one patient in this study had a suspected cholangiocarcinoma, and conventional duodenoscopy and gastroscopy could not meet the diagnostic and therapeutic requirements because of the “hidden” anastomosis. Duodenal endoscopy could not expose the anastomotic site, but gastroscopy was prone to slipping.

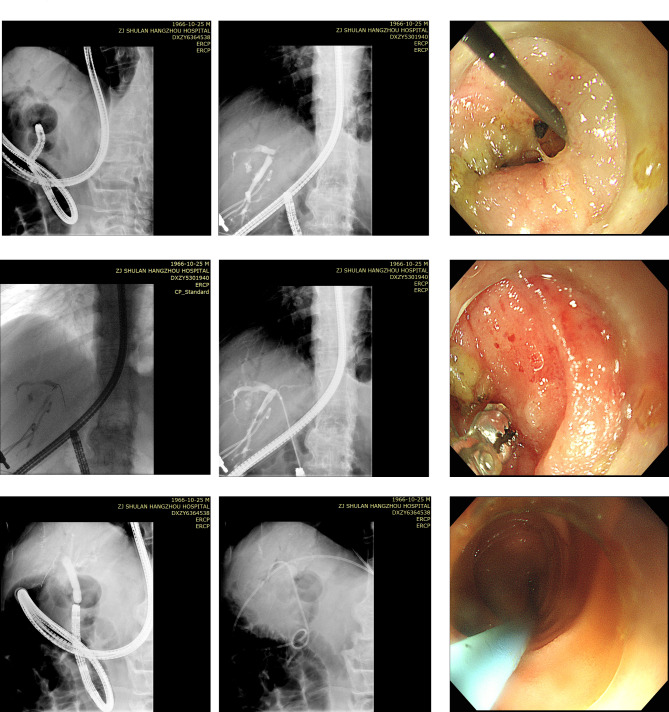

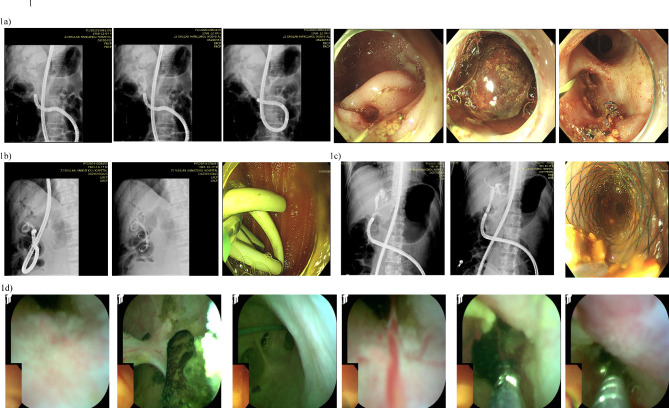

After successful intubation, subsequent endoscopic diagnosis and treatment procedures included ERC stone removal and nasobiliary duct drainage (Fig. 1a), placement of a plastic afferent loop stent (Fig. 1b), placement of a metal biliary stent (Fig. 1c), and cholangioscopic biopsy with the EyeMax system (Fig. 1d), among others. Short SBE-assisted ERC combined with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage resolved the biliary obstruction in some patients (Fig. 2).

Presentation of cases. (a) Choledocholithiasis. (b) Placement of intestinal plastic stent. (c) Placement of biliary metallic stent. (d) Cholangioscopic biopsy with EyeMax system.

In univariate analysis, factors associated with failed intubation included a history of gastrectomy (p <

< 0.05) and Roux-en-Y reconstruction (p

0.05) and Roux-en-Y reconstruction (p <

< 0.05) (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, we found that Roux-en-Y reconstruction (hazard ratio, 4.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.1–15.8; p

0.05) (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, we found that Roux-en-Y reconstruction (hazard ratio, 4.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.1–15.8; p =

= 0.033) was the only independent factor for intubation failure (Table 3).

0.033) was the only independent factor for intubation failure (Table 3).

Table 3

Analysis factors associated with intubation failure.

| Logistic regression | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | P value | P value | HR | 95% CI |

| Age | 0.946 | / | / | / |

| Gender | 0.856 | / | / | / |

| BMI | 0.876 | / | / | / |

| Etiology for SAA | 0.134 | / | / | / |

| History of gastrectomy | 0.001 | 0.242 | / | / |

| History of heptectomy | 0.565 | / | / | / |

| Roux-en-Y reconstruction | 0.001 | 0.033 | 4.2 | 1.1–15.8 |

| ALB pre-ERCP | 0.817 | / | / | / |

| ALT pre-ERCP | 0.081 | / | / | / |

| AST pre-ERCP | 0.222 | / | / | / |

| GGT pre-ERCP | 0.875 | / | / | / |

| AKP pre-ERCP | 0.838 | / | / | / |

| TB pre-ERCP | 0.198 | / | / | / |

| DB pre-ERCP | 0.204 | / | / | / |

| Overtube for short SBE | 0.369 | / | / | / |

| Transparent cap for short SBE | 0.306 | / | / | / |

HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; BMI: body mass index; ALB: albumin; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; GGT: γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; AKP: alkaline phosphatase; TB: total bilirubin; DB: direct bilirubin; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; SBE: single-balloon enteroscopy; SAA: surgically altered anatomy.

Mild post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred in a 61-year-old patient with a native papilla post-Billroth II anastomosis due to gastric cancer. No patients developed perforation or massive bleeding related to the endoscopic procedures.

Discussion

BAE has greatly improved the performance of ERCP in patients with SAA and has become the first-line treatment3,21–31. However, the working length of conventional DBE and SBE scopes is 200 cm, and the lack of ERCP accessories limits their clinical application. To circumvent this limitation, short-type DBE scopes and short SBE scopes have come into use17,28,32–35, with a working length of 155 and 152 cm, respectively. In one study, the total procedural success rate of short SBE-assisted ERCP ranged from 70.4 to 85.9%36. Short DBE showed a similar success rate33–35.

Identifying and intubating the afferent limb is the first and most critical step for successful endoscopic procedures. Skinner et al31. reported that in most patients who have undergone Billroth II gastrojejunostomy, the afferent limb entrance is located on the right side. Tanisaka et al36. stated that the steepest bend occurs in the afferent limb in patients who have undergone Billroth II gastrojejunostomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy. The afferent limb entrance is not recognized in up to half of patients with a history of Roux-en-Y surgery. Tsutsumi et al37. recommended advancing the short SBE scope to the middle loop in patients with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (side-to-side jejunojejunostomy), which can help to reach the papilla of Vater or pancreaticobiliary-enteric anastomosis. Mönkemüller et al38. and Moreels et al39. recommended using fluoroscopy control to aid in the localization of the jejunojejunal anastomosis. They also recommended using fluoroscopy to identify the movement of the short SBE scope toward the liver shadow, indicating successful intubation of the afferent limb. Several methods are available for identifying the afferent limb, such as finding a disruption of the transverse folds or using intraluminal indigo carmine injection or carbon dioxide insufflation at the Roux-en-Y anastomosis36,38,39.

The “push and pull” method for safe and smooth advancement of the short SBE scope along the intestinal wall has been discussed in detail19,31,36, as has the maneuver for use of an overtube31,36. In some difficult cases, the patient’s position must be changed or abdominal pressure must be applied18,31. Occasionally, the surgeon must wait for favorable intestinal peristalsis before intubation can be performed, when the operating part of the short SBE scope is almost fully pressed against the patient’s mouth. The “wait and go ahead” principle should be adopted. In our center, we also use the method of dragging the retrieval balloon back to drive the enteroscope forward.

The SIF-H290S used in the present study is a relatively new type of short SBE scope that was introduced in Japan in 201617. Despite our patience, perseverance, and use of all aforementioned techniques, the enteroscopy success rate is lower (only 57.6%) and the intubation time is longer in the present study than in previous studies17,28,31,36. There are several possible reasons for this. First, most of the patients in this study had malignancies (41.4% of procedures). Second, the heterogeneity of surgical quality may have led to an excessive length or angle of the afferent loop. Third, the proportion of patients undergoing endoscopic procedures after Roux-en-Y reconstruction was 47.5%. Previous research has demonstrated that Roux-en-Y anastomosis and malignancies are the main risk factors for procedural failure40. In addition, a transparent hood has been found to be useful for enteroscope insertion to the afferent limb41. However, the present study did not yield such results. During endoscopic intubation in some cases, we found that the majority of the body of the short SBE scope was coiled within the stomach cavity. Therefore, we believe that gastrectomy is beneficial for intubation. In addition, compared to previous studies, our study did not yield such positive outcomes. Moreover, we found that Roux-en-Y reconstruction was the only independent factor related to intubation failure in this study.

Adverse events may occur when inserting the enteroscope to the target site, including intestinal bleeding and perforation, particularly in patients with tight adhesions18. In one study, intestinal perforation occurred in 1.9% of patients40. In the present study, only one patient with choledocholithiasis after Billroth II anastomosis due to gastric cancer developed mild postoperative pancreatitis. No major adverse events occurred, such as significant post-ERCP bleeding or perforation. In fact, our experience has shown that removing plastic stents through the enteroscopy site is much more difficult than inserting plastic stents. The nasobiliary duct can be used as a substitute. Simultaneously or subsequently incising the nasobiliary duct and retaining it within the stomach is beneficial for stent removal.

PTCD is a remedial method for failed short SBE-assisted ERCP18. Short SBE-assisted ERCP using the rendezvous technique may be helpful for patients with a sharply angulated Roux-en-Y limb31,42. A motorized spiral enteroscope (SE) (PSF-1; Olympus Medical Systems) with a working length of 168 cm and a working channel diameter of 3.2 mm has been available since 2015. Motorized SE-assisted ERCP in patients with SAA reportedly facilitates successful and rapid enteroscopic access and cannulation18,43. However, the motorized SE has been recently withdrawn from the market due to related complications. Alternative treatment modalities have also been recently developed, including laparoscopy-assisted ERCP and interventional endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)18. Laparoscopy-assisted ERCP reportedly achieved high success rates in some patients with a history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery44. Interventional EUS also provides a higher success rate and shorter procedure time than balloon enteroscopy-assisted ERCP in some patients with SAA18,45. Moreover, EUS-directed transgastric ERCP, a recently emerging technique, may be superior to laparoscopy-assisted ERCP because of its shorter procedure time and length of hospital stay46,47.

Conclusion

Short SBE is a safe first-line method for managing pancreatobiliary disease in patients with SAA. Difficult cases, particularly those involving patients with a history of Roux-en-Y reconstruction, require the combination of other methods or the search for alternative solutions.

Author contributions

Sm.D, Ss.Z and Qy.L contributed in conception, design, and statistical analysis. Sm.D, Sj.D, Hk.Z, and Yt.H contributed in data collection and manuscript drafing. Ss.Z and Qy.L supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Declarations

All other authors disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Articles from Scientific Reports are provided here courtesy of Nature Publishing Group

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79633-3

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-79633-3.pdf

1,2

1,2