Abstract

Free full text

Microchimerism, Dendritic Cell Progenitors and Transplantation Tolerance

Abstract

The recent discovery of multilineage donor leukocyte microchimerism in allograft recipients up to three decades after organ transplantation implies the migration and survival of donor stem cells within the host. It has been postulated that in chimeric graft recipients, reciprocal modulation of immune responsiveness between donor and recipient leukocytes may lead, eventually, to the induction of mutual immunologic nonreactivity (tolerance). A prominent donor leukocyte, both in human organ transplant recipients and in animals, has invariably been the bone marrow-derived dendritic cell (DC). These cells have been classically perceived as the most potent antigen-presenting cells but evidence also exists for their tolerogenicity. The liver, despite its comparatively heavy leukocyte content, is the whole organ that is most capable of inducing tolerance. We have observed that DC progenitors propagated from normal mouse liver in response to GM-CSF express only low levels of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II antigen and little or no cell surface B7 family T cell costimulatory molecules. They fail to activate resting naive allogeneic T cells. When injected into normal allogeneic recipients, these DC progenitors migrate to T-dependent areas of host lymphoid tissue, where some at least upregulate cell surface MHC class II. These donor-derived cells persist indefinitely, recapitulating the behavior pattern of donor leukocytes after the successful transplantation of all whole organs, but most dramatically after the orthotopic (replacement) engraftment of the liver. A key finding is that in mice, progeny of these donor-derived DC progenitors can be propagated ex vivo from the bone marrow and other lymphoid tissues of nonimmunosuppressed spontaneously tolerant liver allograft recipients.

In humans, donor DC can also be grown from the blood of organ allograft recipients whose organ-source chimerism is augmented with donor bone marrow infusion. DC progenitors cannot, however, be propagated from the lymphoid tissue of nonimmunosuppressed cardiac-allografted mice that reject their grafts. These findings are congruent with the possibility that bidirectional leukoeyte migration and donor cell chimerism play key roles in acquired transplantation tolerance. Although the cell interactions are undoubtedly complex, a discrete role can be identified for DC under well-defined experimental conditions. Bone marrow-derived DC progenitors (MHC class II+, B7-1dim, B7-2−) induce alloantigen-specific hyporesponsiveness (anergy) in naive T cells in vitro. Moreover, costimulatory molecule-deficient DC progenitors administered systemically prolong the survival of mouse heart or pancreatic islet allografts. How the regulation of donor DC phenotype and function relates to the balance between the immunogenicity and tolerogenicity of organ allografts remains to be determined.

Introduction

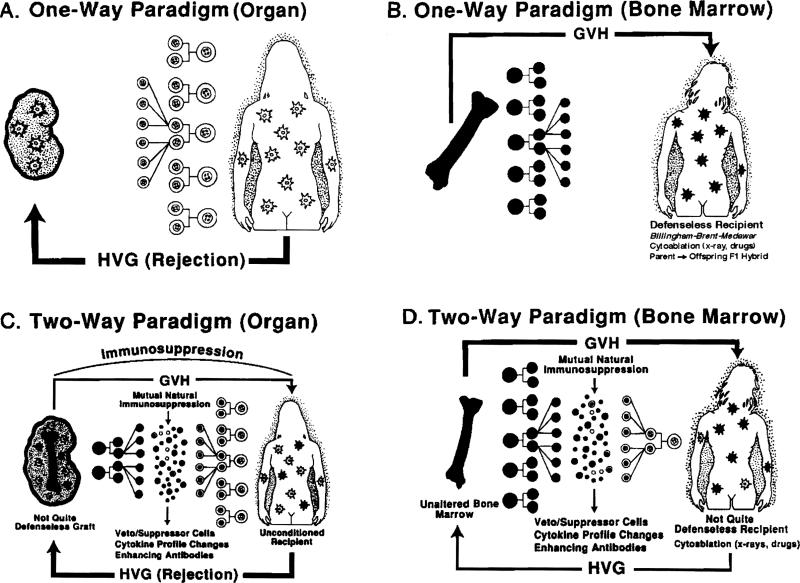

Ever since the landmark contributions of Billingham, Brent and Medawar [1, 2], transplantation has been defined largely in terms of a unidirectional immune reaction: host-versus-defenseless-graft (HVG) following organ transplantation (Fig. 1A) and graft-versus-defenseless-host (GVH) after bone marrow transplantation (Fig. 1B). In either direction, this one-way paradigm has failed to elucidate numerous enigmatic observations including the surprising clinical success of these procedures. However, it now appears that the events following both varieties of transplantation may be explained by the previously unsuspected persistence of a trace population of immune cells [3-6]. The trace population after organ transplantation (microchimerism) was discovered in 1992 when donor leukocytes were found in the skin, lymph nodes, blood and other locations in patients whose kidney or liver allo-grafts had been functioning for up to 30 years [3, 7]. The implication was that donor stem cells present in the transplanted organ had migrated and survived in the recipient [8-10] (Fig. 1C).

The one- and two-way paradigms of immune interaction following organ or bone marrow transplantation.

In the mirror image condition that evolves after conventional clinical bone marrow transplantation [3, 10], the trace population consists of leukocytes of host origin (Fig. 1D), meaning that recipient stem cells survive and persist despite patient preconditioning with supralethal cytoablation [11, 12]. With either conventional organ or bone marrow transplantation, the quantitative disproportion of the coexisting donor and recipient leukocytes is enormous. Nevertheless, there is much circumstantial and direct evidence that the two cell populations reciprocally modulate immune responsiveness, including the induction of mutual nonreactivity (the two-way paradigm). The implications of this concept at virtually every level of transplantation immunology have been discussed elsewhere [3-10, 13]. Here, we will consider mechanisms by which the trace populations of donor cells are sustained and function after organ transplantation.

The distribution of the post-organ transplant microchimerism is not homogeneous in host recipient tissues [4, 14, 15]. When the blood compartment is serially sampled, donor cells wax and wane [16, 17] presumably reflecting cyclic activity of stem cells after their migration from the transplanted organ. This assumption was supported by Taniguchi et al. [18] who showed that pluripotent stem cells purified from adult mouse livers unfailingly reconstituted all hematolymphopoietic lineages in supralethally irradiated mouse recipients. In equally convincing experiments, one of our researchers (Noriko Murase) demonstrated that supralethally irradiated adult rats wcre similarly rescued by syngeneic liver transplantation (Fig. 2). Heart transplantation also had a less dramatic but significant therapeutic effect which resulted in permanent full multilineage reconstitution and survival of one of six animals and prolongation of survival in four others (Fig. 2). In contrast, animals given 3 ml blood (far more than potentially trapped blood in the rinsed organs) died at the same time as untreated controls. One-half million fresh bone marrow cells were ineffective whereas all animals given one or five million bone marrow cells survived (Fig. 2). Such experiments have made it clear that the difference between the chimerism (and tolerance) produced by classical bone marrow transplantation, and that induced by the donor leukocytes that are normal constituents of all whole organs, is purely semantic.

Median survival time (days) of adult Lewis (LEW) rats after lethal irradiation and syngeneic organ or hone marrow transplantation. The rats were lethally irradiated (9.5 Gy) and transplanted with a heart or liver organ graft from naive syngeneic donors. The end point of this experiment was animal survival, which depended on the ability of hematopoietic progenitor cells contained in the organ grafts to reconstitute the lethally irradiated recipients. Different numbers of unfractionated LEW bone marrow cells (0.5, 1.0, or 5.0 × 106) or whole blood (3 ml) were also infused to lethally irradiated LEW recipients to identify the minimum number of bone marrow cells necessary for reconstitution.

Although the microchimerism is multilineage, dendritic leukocytes (commonly termed dendritic cells [DC]) have invariably been prominent donor cells in human organ recipients [3-8] and in experimental animal models [14, 15]. Consequently, we will focus in this review on studies of DC and their progenitors in mouse liver, heart and bone marrow and of host and donor-derived DC in lymphoid tissue of recipients of these organs [19-24]. The cell culture methods used were modified from the technique described by Inaba and Steinman et al. in 1992 for the propagation of mouse blood [25] and bone marrow DC [26] in response to GM-CSF. Similar studies on rat bone marrow-derived DC have permitted the extensive characterization of these cells [27]. We have also succeeded in propagating donor-derived DC from the peripheral blood of donor bone marrow-augmented human organ transplant recipients (see below).

Choice of Liver and Heart for Study

Transplantation of the liver and heart lead to different immunologic outcomes under specifically defined experimental circumstances. However, information obtained first in humans [3, 4] but most completely in rat and mouse experiments [14, 15, 28] suggests that hepatic tolerogenicity is merely an extreme example of a phenomenon common to all organized tissues and organs, with variations in outcome dictated by the quantity and lineage profile of leukocytes in the grafts. Consequently, the liver and heart with their high and low chimerism potential, respectively, were chosen for the study of progenitor and stem cells.

The Liver

In several species including humans, an hepatic allograft transplanted after removal of the recipient's own liver can induce donor-specific tolerance under a temporary umbrella of immunosuppression [29-31]. In fact, permanent graft acceptance in various animal models occurs without any treatment at all. This is seen unpredictably in outbred swine [32-34] but consistently across a limited number of rat donor/recipient strain combinations [35, 36], and in almost all mouse liver recipients, irrespective of the histocompatibility barrier [15]. The auto-induction of graft acceptance by the liver, whether spontaneous or initially “assisted” with immunosuppression, extends to other tissues or organs transplanted concomitantly or subsequently from the same donor or donor strain [35, 37, 38]. We have ascribed this hepatic tolerogenicity to hematopoietic “passenger leukocytes” of bone marrow origin that migrate from the liver after transplantation and establish residence ubiquitously in the recipient. Additionally, the liver is resistant to hyperacute (humoral) rejection and shields other donor organs from this potential complication. The latter quality may be explained in part by the prompt change in the recipient's complement to predominantly donor type after liver replacement [39].

The Heart

An ectopically placed heart allograft (within the abdomen) is also potentially tolerogenic but weakly so compared to the orthotopically transplanted liver. In observations that were inexplicable in 1973, Corry et al. [40] described spontaneous heart allograft acceptance using a mouse strain combination with a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I disparity (B1.AKM→B10.BR). Russell et al. [41] showed that mice which permanently accepted kidneys from significantly histoincompatible animals without treatment were subsequently tolerant to donor strain skin. Further, Murase et al. [28] have demonstrated cardiac tolerogenicity in the rat.

Choice of Species

The mouse was the natural choice for the progenitor cell studies. Unlike in the rat or human, there are several DC lineage-restricted markers in the mouse (33D1, nonlymphoid DC [NLDC]145, and CD11c [N418]) that can be identified using monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) [42,43]. This added to the attractiveness of mouse models for the study of properties of DC and their progenitors in lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs. Most previous similar mammalian investigations have been with this species, from which conclusions about tolerance phonomenology have been freely extrapolated to higher species. The tolerance induced by mouse and rat hepatic allografts (to self and other donor organs) occurs in spite of retention of donor-specific mixed leukocyte reactivity (MLR) and cell-mediated lymphocytotoxicity (CML) (split tolerance) [28, 31, 44], a feature also observed after the transplantation of various organs in humans [7, 8]. Surprisingly, in the rodent models, graft acceptance is not associated strongly with a T helper-1 (Th1)→Th2 transition of the cytokine profile [45] or with the number, phenotype, or cytotoxic potential of graft-infiltrating cells [46]. It is noteworthy that the timc for establishment and maintenance of chimerism and stable tolerance is shortest in the mouse, next in rats and longest in humans.

Although nonrejecting heart transplant models like those in the mouse have not been reported in rats, prolonged drug-free heart graft survival can be induced in several strain combinations by administering perioperative immunosuppression. With a Lewis→Brown Norway rat transplantation model and a short course of tacrolimus (formerly FK 506), it was possible to determine the relative tolerogenicity and the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GYHD), associated with four organs (liver, heart, kidney and intestine) and four tissue cell suspensions (2.5 × 108 cells) prepared from bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes or thymus [28]. The spectrum of tolerogenicity (without GVHD) was liver best→bone marrow cells next→heart least. The outcome with all of these cell or organ transp] antations in rats was strongly correlated with the degree of chimerism and also the lineage composition that was produced. The engrafted donor leukocytes always included T and B lymphocytes. However, the most prominent population when the allografts induced tolerance without GYHD consisted of cells of myeloid lineage, notably DC [28].

The Dendritic Cell: Classical and Changing Perceptions

The ubiquitous presence of donor DC in human [3-8] and animal whole organ recipients [14, 15] suggested that these cells hold the key to tolerance induction. This was conceived to be paradoxical at first. Because lymphoid DC are the most potent antigen-presenting cells (APC) and the only population that can activate unprimed T lymphocytes [47], they had been widely considered a problem to be overcome, not the solution to achieving transplant tolerance. Within organs [48] or after their migration to the spleen [49], DC were implicated as the mediators of primary stimulation of the immune response against donor antigen [50]. The migratory properties of DC are well adapted for this role [47, 49-51]. They are widely dispersed in lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs and in the circulation [47, 52]. Consequently, depletion of DC from allografts in order to reduce immunogenicity was a major theme in the transplantation literature throughout most of the first two decades after Steinman and Cohn [53] delineated these leukocytes as a separate lineage [53-55]. Until 1992, the therapeutic implications of the highly immunogenic DC were seen almost exclusively in the context of vaccine development and potential immunostimulation strategies for immunocompromised patients.

There were, however, hints in the literature that DC, the most effective activators of mature T cells, could also tolerize developing T cells. Based on studies of lymphocytes maturing in chimeric mouse thymuses in vitro, Jenkinson et al. [56] suggested that lymphoid stem cells entering the thymus might acquire tolerance to MHC antigens of their own haplotype by interaction with DC, the precursors of which also migrate to the thymus. Matzinger and Guerder [57] further showed that tolerance was not uniquely induced by thymic APC, but that DC from spleen (the most potent activators of mature T cells) could also inactivate developing T cells. It was also suggested that, as with mature T cells [58], T cell receptor (TCR) engagement of self-antigen by developing thymocytes in the absence of a second signal from bone marrow-derived APC could lead to clonal anergy [59].

There were further suggestions that DC could play a role in shaping peripheral tolerance [60]. DC pulsed with high doses of tumor antigen could inhibit antitumor immunity [61]. The potential of DC to control autoimmune responses by stimulating syngeneic MLR [62] and by implication, the induction of suppressor cells [63] had also been shown. More recently, DC transfer (from pancreatic lymph nodes) has been found to prevent diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice [64], whereas autoantigen (myelin basic protein)-pulsed thymic DC have induced specific peripheral tolerance in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis [65]. Shortman and his colleagues [66] have recently proposed the existence of subpopulations of mouse CD8+ lymphoid DC with a “veto” function. It has been further suggested that these CD8+ DC may contribute to Fas-induced apoptosis in peripheral CD4+ T cells [67].

The Nature of DC

DC are derived from CD34+ bone marrow precursors [68] and may share a common bone marrow progenitor with macrophages [69]. They were first isolated from mouse lymphoid tissues, in particular the spleen [53-55], in the course of studies on the function of immune accessory cells in culture. The cell surface phenotypic markers of lymphoid DC [51, 70] indicate that they are not some kind of aberrant macrophage, but indeed belong to a unique lineage. As do all leukocytes, they express CD45 (leukocyte common antigen) but unlike macrophages, they express low levels of Fc and complement receptors. They do not react with many mAbs directed against mononuclear and polymorphonuclear phagocytes (e.g., CD13-15, the CD16 and CD64 Fc receptors and the mouse macrophage marker SER-4). Furthermore, DC do not generally express T cell markers (e.g., CD3). Some human DC, however, express CD4. DC subsets in mouse thymus or bone marrow may express CD4 or CDS. DC do not express TCR, B cell markers (e.g., membrane immunoglobulin, CD19-22), or CD56/57 (natural killer [NK] cells). An important characteristic of (mature) lymphoid DC is that they constitutively express high levels of MHC class II molecules, whereas in macrophages and certain populations of DC (often alluded to as “immature”) expression of MHC class II is inducible in response to various cytokines. DC in secondary lymphoid tissues are located in T cell areas (interdigitating cells) and in splenic marginal zones; in the thymus, they are in the medulla. Cells that are indistinguishable from lymphoid DC have also been isolated from human peripheral blood. There is evidence that at least some of these cells in the bloodstream are migratory, moving from bone marrow to tissues or originating from nonlymphoid tissue and making their way to lymphoid organs.

How do DC Stimulate T Cells?

Compared to macrophages, mature DC within secondary lymphoid tissues take up or process antigen only weakly, but have the unique capacity to trigger primary T cell responses both in vitro and in vivo. They present foreign peptide-MHC complexes to resting T cells and have the capacity to deliver an array of costimulatory signals for T cell activation. This may involve antigen-independent, intercellular adhesion systems that operate before antigen recognition via the TCR, but which facilitate delivery of as yet unidentified DC-derived cytokines. Unlike macrophages, DC cannot produce (or produce only low levels of) interleukin 1 (IL-1) [70]. There is evidence that, like activated macrophages, mature DC produce IL-12 [71] that directs naive T cells towards a Th1 pattern of cytokine production. Although both macrophages and DC express GM-CSF receptors (GM-CSFR), only macrophages express M-CSFR [72]. Intimate contact between the DC and T cells may facilitate the delivery of activation signals via a variety of defined pathways, including B7/CD28, leukocyte function antigen-3 (LFA-3) [CD58]/CD2 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) [CD54]/LFA-1 [73-76], or via DC-restricted molecules, such as N418 (CD11c) in the mouse. Other potential T cell signaling molecules expressed by DC include CD5 [77, 78], MHC class I molecules [79, 80], the various isofomls of CD45 [81], heat stable antigen (HSA) and CD40.

DC Heterogeneity

DC subsets located in distinct compartments within the blood or the same (lymphoid) tissue (e.g., the mouse spleen or thymus) can exhibit phenotypic heterogeneity with respect to the expression of DC-restricted markers, MHC class II and T cell costimulatory molecules [51, 82]. This may reflect possible functional differences. Indeed evidence has emerged from several laboratories to support functional heterogeneity of DC and the presence both of precursor and mature DC within blood, lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues [83-89].

DC in Nonlymphoid Organs

Members of the DC lineage are believed to be distributed ubiquitously. Until recently, little was known about the properties of potential migratory DC resident in nonlymphoid organs, i.e., the liver, heart and kidney, that are commonly transplanted. Although the migration of DC from liver [15] or cardiac allografts [49] to T-dependent areas of recipient spleens has been studied in mice, the functional properties of these cells, or of the precursors from which they are derived have only recently been described [19, 21, 88, 90]. The best characterized DC isolated from nonlymphoid tissues are the MHC class II+ epidermal Langerhans cells (LC) [91]. When freshly isolated, these cells have a phenotype distinct from “mature” lymphoid DC and can process exogenous antigens. They possess Fc receptors, lysosomal enzymes, and some macrophage markers and exhibit avid phagocytic activity. However, they express low levels of critical cell surface costimulatory molecules (B7-1 and B7-2) and are poor initiators of naive T cell responses. Such cells may have tolerizing potential. When cultured in GM-CSF, however, LC can mature into cells resembling lymphoid DC [92-95]—their phagocytic and antigen-processing activities are lost. They upregulate cell surface MHC class II antigen expression and become mature, potent APC with costimulatory activity for T cells [93]. This transformation is accompanied by phenotypic remodeling of the cell surface and changes in other properties [94-96]. Thus, freshly isolated mouse LC express CD32 (FcγRII) receptors and the “macrophage” marker F4/80, but not IL-2 receptors (IL-2R) (CD25); cultured LC, on the other hand, attain a low buoyant density and have the reciprocal cell surface phenotype. CR3 (CD11b/CD18) and the nonlymphoid DC marker NLDC145 are, however, retained during maturation. Recent evidence indicates that the expression of at least two (T cell) costimulatory molecules (B7-1 [CD80] and B7-2 [CD86]) on mouse LC is upregulated with enhanced immunostimulatory function [87, 97].

Recently, it has been shown that, like fresh LC, DC isolated from mouse kidneys and hearts cannot stimulate allogeneic T cells unless cultured overnight [88]. These DC from nonlymphoid organs thus resemble immature rather than mature DC. The immunostimulatory function reported for all DC isolated from nonlymphoid organs may therefore be a consequence of in vitro maturation in culture. The hypothetical stages of DC maturation can be outlined as shown in Table 1.

Table I

Hypothetical stages of dendritic cell (DC) maturation (modified after Austyn; [51])

| Stage | Location | Phenotype | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| DC Progenitors | bone marrow and blood; thymus; nonlymphoid and secondary lymphoid tissue | MHC cl II−/dim | Give rise to DC |

| “Immature” DC | Skin epidermis (LC); interstitial DC in other nonlymphoid organs | FcR+; B7− MHC cl I+/II+ | Antigen uptake and processing; expression of antigen peptide-MHC complexes; poor allostimulatory capacity |

| Migratory DC | Blood and afferent lymph DC | Heterogeneous (transitional) | Migration to 2° lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues |

| Mature DC | Lymphoid tissue | FcR− B7+; MHC cl I+/IIhigh; DC-restricted markersa (heterogeneous) | Presentation of antigenic peptide-MHC complexes and costimulatory signals to T cellsb |

DC Progenitors as Candidate Tolerance-Inducing Cells

The possibility has been raised that resident, unperturbed, costimulatory molecule-deficient DC within nonlymphoid tissue may have tolerizing potential. Experiments addressing this issue, however, have been compromised by a lack of solid organ-derived cells (DC) to test with the T cells of the recipients. Development of the means to propagate DC progenitors from mouse liver in response to GM-CSF [19] provides a basis upon which to test the hypothesis, both in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, the availability of growth factors (GM-CSF [25, 26], tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [68, 98, 99], IL-4 [99], stem cell factor [100] and others) that induce proliferation and influence maturation of DC progenitors offers a means of investigating the regulation of the liver DC phenotype and function in relation to hepatic tolerogenicity/immunogenicity.

Difficulties Encountered in Studying Liver and Other Nonlymphoid Organ DC

Although presumptive interstitial DC have been demonstrated previously by immunohistochemical methods in the portal triads of normal rodent [90, 101-103] or human [104] liver and in the heart [101-103], little has been documented about their function, especially in relation to the activation of naive T cells. Our studies [90] have shown that a population of “mature” DC similar in function to the prototypic spleen DC [53-55] can be isolated from the nonparenchymal cell (NPC) population in normal mouse liver by overnight culture and differential centrifugation. These cells exhibit potent allostimulatory activity for unprimed T cells. However, isolation methods for these liver DC include steps that may induce phenotypic and functional change. In addition, these cells represent only a small percentage of the leukocyte populations and of other potential APC resident in normal mouse liver.

Propagation of Liver DC Progenitors in Response to GM-CSF

Following reports by Steinman's group that large numbers of DC progenitors could be induced to proliferate from normal mouse blood or bone marrow when cultured with GM-CSF [25, 26], we determined whether, using a similar approach, liver-derived DC progenitors could be propagated in liquid cultures. After four days of culture of liver NPC, during which nonadherent granulocytes were removed by gentle washes, growth of cell “clusters” attached to a layer of adherent cells was evident [19]; many dendritic-shaped cells appeared to have been released from the clusters and exhibited “sheet-like” cytoplasmic processes. With more prolonged culture in GM-CSF, these cells detached from the aggregates and many mononuclear cells, with a typical dendritic shape, were seen either loosely attached or floating in the culture medium. However, in the absence of GM-CSF, no cellular proliferation was seen. Adherent macrophages and fibroblasts also expanded in the liver cell cultures in the presence of GM-CSF, but remained firmly attached to the plastic surface. The floating or loosely adherent, putative liver DC were harvested by gentle aspiration for further phenotypic or functional analyses. By day 7 of culture, approximately 2.5 × 106 of these cells per normal mouse liver could be harvested from the cultures.

The surface immunophenotype of cells released from proliferating liver cell aggregates was determined by flow cytometric analysis after 6-10 days or further periods of culture in GM-CSF. Staining for cells of lymphoid lineage, including NK cells, was absent. The floating cells in the liver-derived cultures strongly expressed surface antigens that are known to be associated with mouse DC (Fig. 3) in addition to other cells. These included CD45 (leukocyte common antigen), HSA, ICAM-1 (CD54), CD11b (MAC-1), and CD44 (nonpolymeric determinant of phagocytic glycoprotein-1 [Pgp.1]). In addition, staining of weak to moderate intensity was observed for the mouse DC-restricted markers NLDC145 (interdigitating cells), 33D1 and N418, and for F4/80 and FcγRII (CD32). The intensity of expression of these markers on GM-CSF-stimulated spleen-derived cells was similar, except that 33D1 and NLDC 145 were slightly more and less intense, respectively, compared to the liver-derived cells.

Merged FACScan® immunophenotypic profiles of GM-CSF-stimulated mouse liver-derived DC progenitors released from cell aggregates in liquid culture (day 10) and examined using rat, hamster or mouse mAbs. [Reproduced from the J Exp Med, 1994;179:1828, by copyright permission of the Rockefeller University Press].

In contrast to the observation of Inaba et al. [25] however, concerning the progeny of circulating DC precursors, and to our own published findings on GM-CSF-stimulated spleen-derived DC [105], liver-derived cells that were similarly propagated expressed only a low level of surface MHC class II (I-Ek) antigen. They were therefore classified as DC progenitors. The intensity of MHC class II expression on the liver DC progenitors could not be increased by using higher concentrations of GM-CSF (0.4-0.S ng/ml) and/or by extending the period of culture for up to four weeks. Similar recent observations of immature (MHC class II−) isolated from the respiratory tract of neonatal rats have shown that these cells are refractory to the stimulatory effects of GM-CSF [106]. The low intensity of MHC class II expression on the liver DC progenitors suggested that these proliferating cells, though possessing several surface markers indicative of developing DC, were still at a phenotypically immature stage of differentiation. Further efforts to induce MHC class II antigen expression included combination of GM-CSF with TNF-α (500 U/ml) and/or interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (1000 U/ml) for up to five days, or culture on a “feeder layer” of irradiated, syngeneic spleen cells. None of these treatments significantly affected the expression of cell surface MHC class II on the putative liver DC progenitors. An important stimulatory factor or cofactor was absent.

Allostimulatory Activity of GM-CSF-Propagated Liver DC Progenitors

In view of the comparatively low cell surface expression of MHC class II on the GM-CSF-stimulated liver DC progenitors, it was of interest to determine their allostimulatory activity. Our prediction was that they would show little or none. When compared to GM-CSF-stimulated spleen cells propagated and harvested using the same techniques, the cultured liver-derived DC progenitors failed to induce naive, allogeneic T cell proliferation as predicted. GM-CSF-stimulated spleen-derived DC, however, which expressed much higher levels of surface MHC class II antigen, were more efficient inducers of quiescent, allogeneic T cells than freshly isolated spleen cells. Furthermore, failure of the GM-CSF-stimulated, putative liver DC progenitors to induce MLR contrasted with the potent allostimulatory activity of an overnight-cultured, nonadherent, low density mature DC-enriched population that was prepared from freshly isolated normal mouse liver NPC, using conventional methods [82]. Next, we tested an extracellular matrix protein (EMP), type-1 collagen, that is spatially associated with liver DC in situ and adherence to which is known to alter both the phenotypic characteristics and function of mononuclear leukocytes [107-109].

Upregulation of DC-Restricted Markers, MHC Class II and Allostimulatory Activity by Exposure of GM-CSF -Stimulated, Liver-Derived DC Progenitors to Type-1 Collagen

Seven-day, GM-CSF-stimulated liver-derived DC progenitors expressing low levels of MHC class II were transferred to culture plates precoated with rat tail type-1 collagen and maintained for three additional days in the presence of GM-CSF. Cell proliferation was observed on the collagen-coated plates, accompanied by a relative increase in nonadherent cells as compared to control cultures (collagen-free). Immunophenotypic analysis of the nonadherent cells showed marked upregulation in the intensity of expression of the DC markers NLDC145, 33D1 and N418. Such upregulation of DC-restricted markers had been shown previously by Inaba et al. in GM-CSF-stimlllated mouse bone marrow cell cultures [26]. Of particular interest, however, was the marked upregulation of cell surface MHC class II expression observed on liver DC progenitors (MHC class IIdim or class II−) propagated for an additional three days with GM-CSF on type-1 collagen-coated plates, as compared to similar cells maintained in collagen-free cultures (Fig. 4) [19]. Following exposure to type-1 collagen, the liver DC progenitors became potent inducers of MLR, in marked contrast to Ia-depleted cells maintained in GM-CSF alone, which failed to elicit T cell proliferation. These MHC class IIbright liver-derived DC also proved more potent MLR stimulators than freshly isolated spleen cells, although not as potent as GM-CSF-stimulated spleen-derived DC. This added further weight to our contention that the liver DC progenitors had undergone maturation following three-day culture in the presence of type-1 collagen and GM-CSF.

Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of MHC class II (I-Ek) on GM-CSF-stimulated mouse liver DC progenitors before and after exposure to type-1 collagen. All Ia+ cells were depleted from 7-d cultures of liver-derived cells released from aggregates in GM-CSF-supplemented medium by treatment with anti-Ia (I-Ek) mAb and complement; the cells were then exposed for a further 3 d to type-1 collagen 1) in the continuous presence of GM-CSF (0.4 ng/ml) or 2) maintained without collagen. An isotype-matched irrelevant antibody was used as a negative control. [Reproduced from the J Exp Med, 1994;179:1830, by copyright permission of the Rockefeller University Press].

In Vivo Migration (Homing) of Liver-Derived DC Progenitors in Allogeneic Recipients

A specialized property of DC is their capacity to “home” to T-dependent areas of peripheral lymphoid tissues [49, 110, 111]. To assess the homing ability of the liver DC progenitors propagated in culture, 10-day GM-CSF-stimulated cells (1 or 2.5 × 105 low I-Ek expression or Ia− following complement-mediated lysis, respectively) were injected s.c. into one hind footpad or i.v. into allogeneic B 10 (I-E−) recipients. For comparative analysis, strongly class II+ GM-CSF-stimulated spleen DC (10-day cultures) were injected into separate animals. One to five days later, the animals were sacrificed, and cryostat sections of the draining lymph nodes (where appropriate) and spleens were stained with donor-specific mAb (anti-I-Ek). Liver-derived DC progenitors, propagated in GM-CSF-supplemented cultures, homed after injection almost exclusively to the T cell areas of recipients’ spleens.

The allogeneic donor cells were found consistently in close proximity to arterioles [19, 21]. Similar observations were also made in the draining lymph node of footpad-injected mice. Moderate to intense I-Ek expression was detected on the liver-derived cells, many of which also exhibited distinct dendritic morphology. At day 5 after injection, liver-derived DC in the recipients’ spleens were more abundant than strong class II+ spleen-derived DC [21], which also homed after injection to T cell areas of recipients’ spleens and lymph nodes. Similar observations were made whether Iadim or Ia-depleted cells were injected. In the latter instance, however, the incidence of positive cells was reduced. These observations suggest that after injection, at least some of the liver DC progenitors upregulate their MHC class II surface antigen. As shown previously for other nonlymphoid organ DC [49, 111], immature liver DC propagated in culture also exhibit a key functional property of this cell lineage—the capacity to home to T-dependent areas of secondary lymphoid tissue and therein to strongly express MHC class II cell surface antigen. Following liver transplantation, the function of these donor-derived cells could influence the balance between the immunogenicity and tolerogenicity of the graft.

Persistence of Liver-Derived DC Progenitors and Their Progeny in Allogeneic Hosts

The foregoing donor MHC class II+ (I-Ek+) cells could still be detected in T cell areas, in the same close proximity to arterioles, at least two months after the injection of liver DC progenitors [21]. Rarely, mitotic figures were observed [21]. These findings are congruent with earlier observations on the persistence of cells with donor phenotype and distinct DC morphology within lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs of orthotopic liver allograft recipients many months after transplantation [3, 4, 15, 28, 112]. In mice, two-color immunohistochemical analysis has confirmed the identity of these cells as donor liver-derived DC [15].

Growth of Donor-Derived DC Progeny from Lymphoid Tissue of Liver-Allografted Mice

Bone marrow or spleen cells were isolated from unmodified mouse orthotopic liver transplant (OLTx) recipients (male B10; [H-2b, I-A+]→female C3H; [H-2k;I-Ek]) 14 days after transplantation. The cells were cultured for 10 days in GM-CSF employing the techniques described above to enrich for DC lineage cells. Using now cytometric and immunocytochemical analysis for donor MHC class I+ and II+ cells, respectively, a minor population of cells of donor phenotype (in addition to recipient cells) was found to propagate in culture. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, using probes specific for the sex-determining region of male donor Y chromosome, or donor MHC class II (in the B10.BR→B10 strain combination) revealed growth of cells of donor origin in bone marrow (especially) (Fig. 5) and spleen cell cultures propagated from female recipients of male livers [22-24]. No signal for donor-derived cells could be detected in 10-day GM-CSF-stimulatcd cultures of thymocytes from liver allograft recipients [23]. This suggested that the thymus may not be an appropriate microenvironmental niche for donor-derived DC progenitors, in spite of the identification there of mature DC [14].

Detection of the donor Y chromosome in freshly isolated (day 0) and 10-d GM-CSF-stimulated bone marrow cells from female (C3H) recipients of male (B10) livers or hearts. The mice were sacrificed 14 d or 8 d, respectively, after transplantation. In this strain combination, liver allografts are accepted spontaneously, whereas heart grafts are rejected with a median survival time of 8 d. Growth of donor-derived cells is evident in the DC cultures propagated from the bone marrow of liver allograft recipients, whereas there is little evidence of survival of male cells in the cultures from heart graft recipients. [Reproduced from the J Exp Med, 1995;182:384, by copyright permission of the Rockefeller University Press].

We next sought direct evidence that the donor-derived cells propagated from the bone marrow of liver allograft recipients were of DC lineage. Sorting of donor-positive cells was considered, but the anticipated yield of cells was calculated to be too low for subsequent functional analysis. Instead, 10-day GM-CSF-stimulated bone marrow-derived cells were harvested, NLDC 145+ cells were sorted (at least 90% purity by morphologic and FACScan® analysis) and then investigated for the presence of donor Y chromosome. As shown in Figure 6, PCR analyses demonstrated convincingly that the highly purified DC population comprised approximately 1-10% Y chromosome-positive (donor-derived) cells in addition to recipient strain DC [23]. Further evidence for the presence of donor-derived DC was obtained by testing the allostimulatory activity of sorted, NLDC 145+ GM-CSF + IL-4-stimulated bone marrow-derived cells in primary MLR. Here, IL-4 was used to promote ex vivo DC maturation, since this was necessary for the detection of allostimulatory activity. The purified NLDC 145+ population propagated from C3H recipients of B10 allografts strongly stimulated B10 (donor strain) responders, but also stimulated a response in recipient strain T cells [23]. The extent of stimulation (p < 0.01 compared to negatively sorted cells or syngeneic DC) was similar to that achieved with “artificial mixtures” containing 1% GM-CSF + IL-4-stimulated donor strain (B10) DC. The in vivo functional role of donor-derived DC progenitors in the lymphoid tissue of spontaneously tolerant liver allograft recipients remains to be determined. The capacity, however, of bone marrow-derived DC progenitors to induce alloantigen-specific anergy in T cells in vitro has recently been demonstrated (see below). An additional consideration is that presentation of allopeptides (derived from donor APC) by recipient DC (the indirect pathway of antigen presentation) [113] may be important for the induction of unresponsiveness.

Demonstration that donor-derived cells in 10-d GM-CSF-stimulated bone marrow cell cultures from liver-allografted mice are DC. PCR analysis of pre- and post-sorted cells, showing the presence of donor-derived Y chromosome in the NLDC 145+ (DC) fraction. [Reproduced from the J Exp Med, 1995;182:383, by copyright permission of the Rockefeller University Press].

Failure to Propagate Donor-Derived Cells from Bone Marrow of Mice Rejecting Heart Allografts

In contrast to liver allograft recipients, nonimmunosuppressed C3H mice reject heart allografts from the same donor strain (B10) within ten days [15]. PCR analysis for donor Y chromosome was performed on 10-day GM-CSF-stimulated cultures of bone marrow cells harvested from heterotopic cardiac allograft recipients eight days after transplant. In contrast to the results obtained from liver graft recipients, no evidence was obtained for the propagation of donor-derived cells from the bone marrow of animals rejecting their cardiac grafts (Fig. 5) despite evidence of small numbers of chimeric cells in freshly isolated bone marrow [23]. Thus heart-derived cells, in contrast to those detected in fresh bone marrow of liver allograft recipients, appear not to contain sufficient numbers of GM-CSF-responsive progenitors for growth of donor-derived cells (as opposed to amplification in the case of liver grafts) after 10 days of culture.

Propagation of Donor-Derived DC from the Blood of Bone Marrow-Augmented Human Liver Allograft Recipients

Donor-derived DC progenitors have also been propagatcd in culture from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of donor bone marrow-augmented human liver transplant recipients. The patients studied have been involved in a trial in which the infusion of unmodified donor vertebral body bone marrow at the time of organ transplant has been performed to augment donor cell microchimerism [114]. Representative data obtained for one bone marrow-augmented liver transplant patient are shown in Figure 7. PBMC were obtained 590 days post-transplant. DC were propagated in GM-CSF + IL-4-enriched medium using a modification of a method described previously [115]. On day 15 of culture, nonadherent cells of dendritic morphology were harvested and subjected to double immunofluorescence staining using a cocktail of phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled lineage-specific (CD3, CD14, CD22 and CD56) and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-HLA-DR antibodies. Subsequent to staining, the lineage− and HLA-DRbright cells were sorted and their purity confirmed by reanalysis. Within the sorted population, the presence of donor DNA (HLA-DR4) was determined by PCR amplication followed by Southern blotting (Fig. 7D, arrow). The knowledge obtained from studies of these donor-derived cells may provide new insight into the mechanistic basis of tolerance induction. It may also aid the development of strategies for the use of cellular immunotherapy to enhance allograft acceptance.

Detection of donor-derived DC in GM-CSF + IL-4-stimulated cultures propagated from the blood of a donor bone marrow-augmented liver transplant patient. PBMC obtained from the liver recipient 590 days post-transplantation were cultured using a modification of a method described previously [115]. On day 15 of culture, nonadherent cells of dendritic morphology were harvested and subjected to double immunofluorescent staining using a cocktail of PE-labeled lineage-specific (CD3, CD14, CD22 and CD56) and FITC-labeled anti-HLA-DR antibodies. Subsequent to staining, the lineage− and HLA-DRbright cells were sorted and their purity confirmed by reanalysis. Within the sorted population, the presence of donor DNA (HLA-DR4) was determined by PCR amplication followed by Southern blotting (D, arrow). A) Scatter profile of cells prior to sorting. Large granular cells within the gated region (R1) were selected for sorting. B) Analysis of autofluorescence of unstained cells within the gated region (A; R1) used to set the quadrants to view positive Fluorescence. C) The purity of the sorted cells (lineage− HLA-DRbright) was increased by creating a decreased sorting region (R2).

Bone Marrow-Derived DC Progenitors Induce Alloantigen-Specific Unresponsiveness (Anergy) in T Cells In Vitro

DC progenitors were propagated from B10 mouse bone marrow in response to GM-CSF. The methods used were similar to those employed to propagate DC progenitors from normal mouse liver. Cells expressing DC lineage markers (NLDC 145+, 33D1+, N418+) harvested from 8-10-day GM-CSF-stimulated bone marrow cell cultures were CD45+, HSA+, CD54+ and CD44+. They were MHC class II+, B7-1dim (CD80dim) but B7-2− (CD86−) (costimulatory molecule deficient) (Fig. 8). Supplementation of cultures with IL-4 in addition to GM-CSF, however, resulted in marked upregulation of surface MHC class II and B7-2 expression [116] (Fig. 8). These latter cells exhibited potent allostimulatory activity in primary mixed leukocyte cultures. In contrast, the cells stimulated with GM-CSF alone were very weak stimulators. They induced alloantigen-specific hyporesponsiveness in allogeneic T cells (C3H) detected upon restimulation in secondary MLR [116]. This was associated with blockade of IL-2 production. Reactivity to third party stimulators was intact. The hyporesponsiveness induced by the GM-CSF-stimulated, costimulatory molecule-deficient DC progenitors was prevented by incorporation of anti-CD28 mAb in the primary MLR. It was reversed by the addition of IL-2 to restimulated T cells [116]. These findings show that MHC class II+ B7-2−DC progenitors can induce alloantigen-spccific hyporesponsiveness in T cells in vitro. Under the appropriate conditions, donor-derived, costimulatory molecule-deficient DC progenitors could contribute to the induction of donor-specific unresponsiveness to graft alloantigens in vivo.

FACScan® profiles of DC progenitors (costimulatory molecule-deficient) and “mature” mouse bone marrow-derived DC. Above, expression of MHC class II (I-Ab), B7-1 and B7-2 on 8-d GM-CSF-stimulated DC progenitors (“immature” DC); below, 8-d GM-CSF + IL-4-stimulated B10 bone marrow-derived “mature” DC. Whereas the mature DC were potent stimulators of allogeneic T cells, the DC progenitors induced alloantigen-specific T cell hyporesponsiveness (anergy). For further details, see Lu et at. [116]. [Reproduced from Transplantation 1995, in press, by permission of Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD]

DC Progenitors Prolong Organ Allograft Survival

We have obtained evidence that GM-CSF-stimulated DC progenitors (B7-2−) capable of inducing T cell hyporesponsiveness in vitro can also prolong heart allograft survival. In the B10→C3H model, 2 × 106 B7-2− B10 DC progenitors were given i.v. seven days before transplantation. These cells significantly prolonged heart graft survival compared to syngeneic (C3H) or third party (BALB/c) cells [117] (Table II). In contrast and as expected, mature (B7-2+) DC reduced mean graft survival time. The nonspecific effect of third party DC progenitors (although significantly less than that of allogeneic cells) is also of interest, although its mechanistic basis is not at present understood.

Table II

Influence of one injection of donor-specific GM-CSF-stimulated DC progenitors (B7-2−) on B10 cardiac allograft survival in C3H mice

| Group | Cells injected (d-7) | n | Graft survival times (days) | Mean ± 1 SD | MST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | None (media control) | 8 | 8(×3), 12, 13(×2), 9, 10 | 10.1 ± 2.2 | 9.5 |

| B | Fresh B10 bone marrow cells | 4 | 12(×4) | 12 | 12 |

| Cultured cells | |||||

| C | B10 (B7-2+) (allogeneic) | 5 | 4(×2), 7, 8, 14 | 7.4 ± 4.1 | 7c |

| D | B10 (B7-2−) (allogeneic) | 8 | 19(×3), 22(×2), 23, 27, 35 | 23.3 ± 5.5 | 22ab |

| E | C3H (B7-2−) (syngeneic) | 4 | 12(×2), 13(×2) | 12.5 ± 0.6 | 12.5 |

| F | BALB/c (B7-2−) (third party) | 6 | 12, 17(×2), 16, 19, 20 | 16.8 ± 2.8 | 17 |

Cells (2 × 106 i.v.) were injected 7 d before heterotopic (B10→C3H) heart transplantation, n = number of mice. MST = median survival time. MST compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Pair-wise comparison by the Wilcoxon Sum Rank Test.

DC Progenitors Prolong Pancreatic Islet Allograft Survival

We have also tested the in vivo relevance of cultured DC progenitors in a pancreatic islet allograft model. Two days after rendering groups of B10 (H-2b; I-A+) mice diabetic with streptozotocin, and seven days before transplantation with 700 islet equivalents (99% pure) under the left renal capsule, the animals received i.v. either culture medium, 2 × 106 allogeneic (B10.BR; H-2k I-E+) or syngeneic, 10-day cultured GM-CSF-stimulated liver DC progenitors or 10-day cultured GM-CSF-stimulated mature spleen DC. Blood glucose and body weights were recorded daily. The graft survival times (Fig. 9) show that GM-CSF-stimulated liver DC progenitors prolong allograft survival [118].

Influence of cultured DC progenitors on B10.BR (H-2k) pancreatic islet allograft survival in B10 mice (H-2b). Cultured liver (L) or spleen (S) derived cells (2 × 106) were injected i.v. 2 d after the recipient animals were made diabetic with i.p. injection of streptozotocin. The animals were maintained on insulin (1-2 IU/day) until pancreatic islet transplantation. Pancreatic islets (700IEq/mouse) were placed beneath the left renal capsule seven days after the injection of cultured GM-CSF-stimulated liver DC progenitors or spleen-derived DC (“mature” DC). For further details, see Rastellini et al. [118]. [Reproduced from Transplantation 1995, in press, by permission of William and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD].

Conclusions

Model systems have been established which allow the evaluation, both in vitro and in vivo, of factors that regulate the growth, phenotype and function of DC. These cells have the capacity to direct the immune response, to determine its strength and to affect the balance between tolerance and immunity. However, it should be emphasized that the DC is only one of the hematolymphopoietic lineages represented in the microchimerism of the successfully engrafted whole organ recipient. The chimerism obviously is dependent on pluripotent stem cells for maintenance. The reductionist approach we have reviewed here could, therefore, distance us from the context we are seeking to understand. That context is one of a complex immune reaction that probably can neither be generated nor efficiently sustained by any single lineage [119]. Nevertheless, understanding the molecular regulation both of MHC class II gene product and T cell costimulatory molecule expression by the donor bone marrow-derived APC, and how this relates to T cell activation or unresponsiveness (ancrgy/clonal deletion) is a central issue in transplantation immunology. Such knowledge may be key to clarifying the role of donor-derived (chimeric) DC in host responses to liver and other whole organ transplants and to further understanding the inherent tolerogenicity that is a feature of all organs but most highly represented by the liver. MHC gene product and costimulatory molecule expression (B7-1 and B7-2 are thought to be the most important) on donor-derived DC may be crucial for effective antigen presentation and Th1 cell activation following liver transplantation. Conversely, their absence on donor-derived APC expressing even low levels of MHC gene products may favor tolerance induction by one or more mechanisms. Indeed, we have shown that, in vitro, bone marrow-derived DC progenitors (MHC class II+ B7-1dim, B7-2−) can induce alloantigen-specific hyporesponsiveness (anergy) in naive T cells. Further information is needed on the in vivo relevance of donor-derived DC progenitors, based on the finding that these cells can be propagated from the lymphoid tissue of spontaneously tolerant mouse liver graft recipients and from the blood of liver transplant patients given donor bone marrow infusions. Significantly, we have found that a single systemic injection of GM-CSF-stimulated DC progenitors can prolong organ (cardiac) and pancreatic islet allograft survival. These ongoing and future studies should shed light on one of the key questions of cellular immunology—the balance between the immunogenicity and tolerogenicity of organ allografts. In addition, they will clarify the potential therapeutic role of DC lineage cells in organ transplantation.

Acknowledgments

We thank our many collcagues who have contributed to these studies and provided stimulating and insightful discussion, in particular Drs. J.J. Fung, M.T. Lotze, S.A. McCarthy, P.A. Morel, S. Qian, W.A. Rudert, R.L. Simmons, W. Storkus, V.M. Subbotin and M. Trucco. The work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant DK 29961-14.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.5530130607

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc2963943?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1002/stem.5530130607

Article citations

Dendritic Cells: A Bridge between Tolerance Induction and Cancer Development in Transplantation Setting.

Biomedicines, 12(6):1240, 03 Jun 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38927447

Review

Subset-specific Retention of Donor Myeloid Cells After Major Histocompatibility Complex-matched and Mismatched Liver Transplantation.

Transplantation, 107(7):1502-1512, 20 Jun 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36584373 | PMCID: PMC10508270

Long-term Persistence of Allosensitization After Islet Allograft Failure.

Transplantation, 105(11):2490-2498, 01 Nov 2021

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 33481552 | PMCID: PMC8289921

Liver transplantation in the mouse: Insights into liver immunobiology, tissue injury, and allograft tolerance.

Liver Transpl, 22(4):536-546, 01 Apr 2016

Cited by: 30 articles | PMID: 26709949 | PMCID: PMC4811737

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

CD39 deficiency in murine liver allografts promotes inflammatory injury and immune-mediated rejection.

Transpl Immunol, 32(2):76-83, 07 Feb 2015

Cited by: 19 articles | PMID: 25661084 | PMCID: PMC4368493

Go to all (111) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Increased apoptosis of immunoreactive host cells and augmented donor leukocyte chimerism, not sustained inhibition of B7 molecule expression are associated with prolonged cardiac allograft survival in mice preconditioned with immature donor dendritic cells plus anti-CD40L mAb.

Transplantation, 68(6):747-757, 01 Sep 1999

Cited by: 51 articles | PMID: 10515374 | PMCID: PMC2978966

Costimulatory molecule-deficient dendritic cell progenitors (MHC class II+, CD80dim, CD86-) prolong cardiac allograft survival in nonimmunosuppressed recipients.

Transplantation, 62(5):659-665, 01 Sep 1996

Cited by: 253 articles | PMID: 8830833 | PMCID: PMC3154742

Identification of donor-derived dendritic cell progenitors in bone marrow of spontaneously tolerant liver allograft recipients.

Transplantation, 60(12):1555-1559, 01 Dec 1995

Cited by: 31 articles | PMID: 8545889 | PMCID: PMC2964062

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIDDK NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: DK 29961-14

Grant ID: R01 DK029961-19