Abstract

Background

Hyperplastic polyposis of the colorectum is a precancerous condition that has been linked with DNA methylation. The polyps in this condition have been distinguished from typical small hyperplastic polyps and renamed sessile serrated adenomas. Sessile serrated adenomas also occur sporadically and appear to be indistinguishable from their counterparts in hyperplastic polyposis.Aims and methods

The existence of distinguishing molecular features was explored in a series of serrated polyps and matched normal mucosa from patients with and without hyperplastic polyposis by assessing mutation of BRAF, DNA methylation in 14 markers (MINTs 1, 2 and 31, p16, MGMT, MLH1, RASSF1, RASSF2, NORE1 (RASSF5), RKIP, MST1, DAPK, FAS, and CHFR), and immunoexpression of MLH1.Results

There was more extensive methylation in sessile serrated adenomas from subjects with hyperplastic polyposis (p<0.0001). A more clearcut difference in patients with hyperplastic polyposis was the finding of extensive DNA methylation in normal mucosa from the proximal colon.Conclusions

A genetic predisposition may underlie at least some forms of hyperplastic polyposis in which the earliest manifestation may be hypermethylation of multiple gene promoters in normal colorectal mucosa. Additionally, some of the heterogeneity within hyperplastic polyposis may be explained by different propensities for MLH1 inactivation within polyps.Free full text

Extensive DNA methylation in normal colorectal mucosa in hyperplastic polyposis

Abstract

Background

Hyperplastic polyposis of the colorectum is a precancerous condition that has been linked with DNA methylation. The polyps in this condition have been distinguished from typical small hyperplastic polyps and renamed sessile serrated adenomas. Sessile serrated adenomas also occur sporadically and appear to be indistinguishable from their counterparts in hyperplastic polyposis.

Aims and methods

The existence of distinguishing molecular features was explored in a series of serrated polyps and matched normal mucosa from patients with and without hyperplastic polyposis by assessing mutation of BRAF, DNA methylation in 14 markers (MINTs 1, 2 and 31, p16, MGMT, MLH1, RASSF1, RASSF2, NORE1 (RASSF5), RKIP, MST1, DAPK, FAS, and CHFR), and immunoexpression of MLH1.

Results

There was more extensive methylation in sessile serrated adenomas from subjects with hyperplastic polyposis (p<0.0001). A more clearcut difference in patients with hyperplastic polyposis was the finding of extensive DNA methylation in normal mucosa from the proximal colon.

Conclusions

A genetic predisposition may underlie at least some forms of hyperplastic polyposis in which the earliest manifestation may be hypermethylation of multiple gene promoters in normal colorectal mucosa. Additionally, some of the heterogeneity within hyperplastic polyposis may be explained by different propensities for MLH1 inactivation within polyps.

Colorectal hyperplastic polyps (HPs) with their characteristic serrated glandular architecture are easily distinguished on morphological grounds from adenomas and have been classified as non‐neoplastic lesions that are lacking in malignant potential.1 While an individual HP may have extremely limited potential for malignant transformation, there are reports linking the condition hyperplastic polyposis (HPP) with colorectal cancer (CRC).2,3,4 This raises the question of whether HPs occurring in the condition HPP are qualitatively different from their sporadic counterparts.

The definition of HPP allows for two major phenotypes: (1) multiple small and mainly distal polyps; and (2) small numbers of large and mainly proximal polyps.5 This morphological heterogeneity may explain why some studies have failed to show a convincing link with CRC.6,7 It is pertinent that investigations that have focused on right sided HPs have suggested that these may be the precursors of the subset of CRC with high level DNA microsatellite instability (MSI‐H) whether presenting in HPP8 or sporadically.9,10,11,12 The first detailed morphological characterisation of large and proximal HPs occurred in the context of HPP.2 The authors argued that the polyps in question were distinct from traditional HPs and that the condition they were describing was more aptly termed serrated adenomatous polyposis. The same authors then went on to demonstrate that identical “sessile serrated adenomas” (SSA) could occur sporadically and described in considerable detail the morphological features that distinguished these lesions from typical HPs.13

Parallel studies focusing on immunohistochemical and molecular changes also showed differences between proximal and distal lesions, whether these were sporadic or presented in the context of HPP. Specifically, proximal polyps and/or polyps with the features of SSA showed more aberrant proliferation,14 and high frequencies of BRAF mutation15,16 and DNA methylation.15,17 In contrast, small and distal HPs had frequent KRAS mutation3,15 or alterations implicating chromosome 1p3 and low frequencies of both BRAF mutation16 and DNA methylation.3,15,17

It is not known if the serrated polyps presenting in HPP are qualitatively different from their sporadic counterparts that are large, proximal, and show the morphological features of SSA. Based on findings with respect to BRAF mutation and DNA methylation, it would appear that the serrated polyps occurring in these two clinical scenarios do not differ qualitatively and the link between HPP and colorectal cancer is observed merely because the polyps are very numerous. Nevertheless, there are grounds for suspecting that the polyps in HPP may differ. A key rate limiting step in the evolution of sporadic CRC with MSI‐H is methylation of the promoter region and subsequent inactivation of the DNA mismatch repair gene MLH1.18 Using immunohistochemistry to test for loss of expression of MLH1 in 44 sporadic serrated polyps that were all resected from the proximal colon, none of the polyps showed even focal loss of MLH1.14 It would therefore appear that loss of expression of MLH1 is an uncommon event in sporadic serrated polyps, although such loss has been described in a selected series of sporadic mixed polyps.19 In contrast, loss of MLH1 has been observed in a high proportion of serrated polyps occurring within the condition HPP.8

In the present study, we have identified three patients with HPP in which the phenotype was particularly severe, as manifested by the presence of at least one CRC, serrated polyps with adenomatous dysplasia (mixed polyps or serrated adenomas), as well as very numerous polyps with the features of SSA. We compared patterns of DNA methylation and expression of MLH1 in polyps and normal mucosa from these patients with samples obtained from patients with only small numbers of right sided serrated polyps. As inhibition of apoptosis has been linked to the aetiology of serrated polyps,20,21 the marker panel for DNA methylation included multiple genes with a proapoptotic function.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissues

Patient Nos 1–3 met one or more of the diagnostic criteria for HPP, each having multiple serrated polyps in the proximal colon of which at least two exceeded 10 mm in diameter.5 The numbers and types of polyps are shown in table 11.. In patient No 2, over 100 polyps were counted and 54 of these were diagnosed histologically. Patient No 4 and 5 presented with proximal CRC and small numbers of proximal serrated polyps that did not meet the criteria for HPP. The serrated polyps in patient No 1–5 were classified as HPs, mixed polyps, traditional serrated adenomas (TSA), and the variant HP described as SSA13 (table 11,, fig 11).). Diffuse mucosal hyperplasia was present in the appendix in patient No 1, 4, and 5. Patient No 1 and No 3–5 were treated by right hemicolectomy and patient No 2 by proctocolectomy. Patient No 6–12 had a single SSA of the proximal colon that was removed endoscopically. Patient No 13–15 had a right sided CRC and at least one right sided HP but only DNA obtained from normal mucosa was tested.

Clinical features and polyp diagnoses in subjects with colorectal cancer (CRC)†

Clinical features and polyp diagnoses in subjects with colorectal cancer (CRC)†| Patient No | Age (y) | Sex | HP | SSA | MP | TSA | AD | CRC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64 | F | 3 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| 2 | 63 | M | 32 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2* |

| 3 | 70 | F | 0 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| 4 | 28 | F | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | 75 | M | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

*A synchronous rectal cancer was not subjected to molecular analysis.

HP, hyperplastic polyp; SSA, sessile serrated adenoma; MP, mixed polyp (all were part SSA, part AD); TSA, traditional serrated adenoma; AD, adenoma; CRC, colorectal cancer.

SSAs contiguous with CRCs from patient No 2, 5, and 6 are not included in the polyp count but the contiguous SSA from patient No 4 was analysed for DNA methylation.

†Respective age and sex for patient No 6–15 with diagnoses presented under methods are: 75 M; 63 M; 65 F; 72 M; 74 M; 64 F; 48 F; 73 F; 74 F; 72 F.

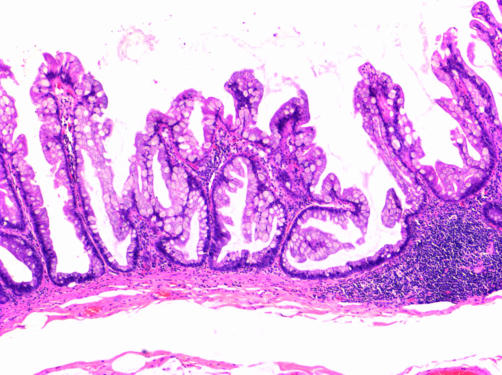

Figure 1 Typical histological appearances of a sessile serrated adenoma from patient No 2. The crypts are dilated and mucin filled, show exaggerated serration, and increased branching, and extend horizontally along the muscularis mucosae. Haematoxylin and eosin stain.

Typical histological appearances of a sessile serrated adenoma from patient No 2. The crypts are dilated and mucin filled, show exaggerated serration, and increased branching, and extend horizontally along the muscularis mucosae. Haematoxylin and eosin stain.

Seven of the CRCs shown in table 11 for patient No 1–5 presented in the proximal colon. Patient No 2 had synchronous rectal cancer arising in a tubulovillous adenoma that was not subjected to further analysis. CRCs in patient No 2, 4, and 5 were contiguous with residual SSA (not included in totals shown in table 11).). None of the patients had inflammatory bowel disease. The study was approved by the institutional review board of McGill University.

MLH1 immunostaining

Immunohistochemical staining for the mismatch repair protein MLH1 was undertaken for 18, 54, and four serrated polyps from patient No 1–3, respectively, and seven CRCs (including any contiguous polyps) from patient No 1–5. Sections (4 μm) of formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissues were cut, mounted onto charged slides, and prepared for incubation with the primary mouse monoclonal antibody to MLH1 (1:100 clone G168‐15; BD Pharmingen, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA), as described previously.14 Loss of MLH1 expression was scored only when there was complete loss of nuclear expression within a distinct subclone or an entire colorectal crypt, including the crypt base cells.

DNA extraction and bisulphite modification

Samples were microdissected from paraffin embedded tissue using two 8 μm thick sections that included 23 SSAs, two mixed polyps, one TSA, two conventional adenomas, and seven CRCs. Care was taken to exclude as much normal mucosa as possible. In the case of polyps, no more than 5% of crypts would have been derived from normal mucosa. Normal mucosa was obtained from two separate samples in patient No 1, 2, 3, and 5, and one sample in patient No 4, 6, and 13–15. Meticulous care was taken to exclude any non‐normal tissue. Samples of normal mucosa were all obtained from the proximal colon. Cell lysis and DNA extraction were performed using a QIAamp DNA mini kit (QlAGEN, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Extracted genomic DNA was diluted in 40 μl of distilled water and denatured by adding 6 μl of 2N NaOH and incubation at 75°C for 20 minutes. Freshly prepared 4.8 M sodium bisulphite (500 μl) and 28 μl of 10 mM hydroquinone were added to the denatured genomic DNA and the reaction was carried out overnight in the dark at 55°C. DNA was then purified using a Wizard DNA clean‐up (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) and then ethanol precipitated after five minutes of alkali treatment with 8.8 μl of 2 N NaOH at room temperature.

Methylation specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Methylation of promoter region of 11 genes and three MINT loci (see below) was examined by methylation specific polymerase chain reaction (MSP) using AmpliTaq Gold kit (Roche, Branchburg, New Jersey, USA). MINT1, MINT2, MINT31, p16 (CDKN2A), MLH1, and O‐6‐methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) have been employed in several previous studies defining CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colorectal polyps and cancers.22,23,24,25,26 RASSF1, RASSF2, and NORE1 (RASSF5) are members of the RAS association domain family (RASSF) of RAS effectors, known to link RAS activation to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.27,28,29,30,31 Mammalian sterile20‐like 1 (MST1) is a ubiquitously expressed proapoptotic protein kinase that mediates the apoptotic effect of RAS by forming a complex with RASSF1/NORE1 and induction of the caspase cascade.31,32,33 The cell surface receptor FAS and death associated protein kinase (DAPK) are known mediators of the extrinsic (death receptor initiated) apoptotic pathway.34,35 Checkpoint gene with forkhead and RING finger domains (CHFR) functions as a mitotic checkpoint to delay entry into metaphase.36 Raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP) negatively regulates mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) by direct binding and inhibition of Raf kinase.37,38 The primer sequences of these genes are listed in table 22.. Conditions for amplification were 10 minutes at 95°C followed by 39 cycles of denaturing at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at certain temperatures (table 22)) for 30 seconds, and 30 seconds of extension at 72°C. PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on 8% acrylamide gels and visualised by SYBR gold nucleic acid gel stain (Molecular Probes, Eugene, USA). CpGenome Universal Methylated DNA (Chemicon, Temecula, California, USA) was used as a positive control for methylation. Gene promoters were considered methylated if the intensity of methylated bands was more than 10% of their respective unmethylated bands.

Primer sequences and methylation specific polymerase chain reaction conditions

Primer sequences and methylation specific polymerase chain reaction conditions| Primer name | Sense primer (5′‐3′) | Antisense primer (5′‐3′) | Annealing temp (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MINT1 | ||||

U U | AATTTTTTTATATATATTTTTGAAGT | AACAAAAACCTCAACCCCACA | 54 | Park23 |

M M | AATTTTTTTATATATATTTTCGAAGC | AAAAACCTCAACCCCGCG | 54 | Park23 |

| MINT2 | ||||

U U | GATTTTGTTAAAGTGTTGAGTTTGTT | CAAAATAATAACAACAATTCCATACA | 54 | Park23 |

M M | TTGTTAAAGTGTTGAGTTCGTC | AATAACGACGATTCCGTACG | 54 | Park23 |

| MINT31 | ||||

U U | TAGATGTTGGGGAAGTGTTTTTGGT | TAAATACCCAAAAACAAAACACCACA | 59 | Park23 |

M M | TGTTGGGGAAGTGTTTTTCGGC | CGAAAACGAAACGCCGCG | 59 | Park23 |

| P16 | ||||

U U | TTATTAGAGGGTGGGGTGGATTGT | CAACCCCAAACCACAACCATAA | 59 | Park23 |

M M | TTATTAGAGGGTGGGGCGGATCGC | GACCCCGAACCGCGACCGTAA | 59 | Park23 |

| MLH1 | ||||

U U | AATGAATTAATAGGAAGAGTGGATAGT | TCTCTTCATCCCTCCCTAAAACA | 54 | Petko41 |

M M | CGGATAGCGATTTTTAACGC | CCTAAAACGACTACTACCCG | 54 | Petko41 |

| MGMT | ||||

U U | TTTGTGTTTTGATGTTTGTAGGTTTTTGT | AACTCCACACTCTTCCAAAAACAAAACA | 59 | Esteller42 |

M M | TTTCGACGTTCGTAGGTTTTCGC | GCACTCTTCCGAAAACGAAACG | 59 | Esteller42 |

| RASSF1 | ||||

U U | TTTAGGTTTTTATTGTGTGGTT | CCAATTAAACCCATACTTCACTAA | 52 | – |

M M | GTATTTAGGTTTTTATTGCGCG | GATTAAACCCGTACTTCGCTAA | 52 | – |

| RASFF2 | ||||

U U | AGTTTGTTGTTGTTTTTTAGGTGG | AAAAAACCAACAACCCCCACA | 54 | Hesson43 |

M M | GTTCGTCGTCGTTTTTTAGGCG | AAAAACCAACGACCCCCGCG | 58 | Hesson43 |

| NORE1 | ||||

U U | AAGGAAGGGGAAATTTAATTAGAGT | CCCCTCTAAAACAAAACTCAACA | 56 | – |

M M | AGGAAGGGGAAATTTAATTAGAGC | CCTCTAAAACGAAACTCGACG | 56 | – |

| MST1 | ||||

U U | TTTTGGTAATGTAGGAAGATAGTGT | AAACCACAACCCTAATCACATA | 54 | – |

M M | GTTTCGGTAACGTAGGAAGATAGC | AACCACGACCCTAATCACGTA | 54 | – |

| FAS | ||||

U U | AATTAATGGAGTTTTTTTTAATTTGG | AACACCTATATATCACTCTTACACAAA | 54 | – |

M M | ATTAATGGAGTTTTTTTTAATTCGG | CACCTATATATCACTCTTACGCGAA | 54 | – |

| DAPK | ||||

U U | GGTAAGGAGTTGAGAGGTTGTTTT | ACCCTACCACTACAAATTACCAAA | 54 | – |

M M | GTAAGGAGTCGAGAGGTTGTTTC | CCTACCGCTACGAATTACCG | 54 | – |

| CHFR | ||||

U U | TTGGTTAGGATTAAAGATGGTTGA | CCCACAATTAACTAACAACAACACT | 54 | – |

M M | TTTGGTTAGGATTAAAGATGGTC | GCGATTAACTAACGACGACG | 54 | – |

| RKIP | ||||

U U | TTTAGTGATATTTTTTGAGATATGA | CACTCCCTAACCTCTAATTAACCAA | 52 | – |

M M | TTTAGCGATATTTTTTGAGATACGA | GCTCCCTAACCTCTAATTAACCG | 52 | – |

BRAF mutation

BRAF mutation analysis at codon 600 (V600E; formerly V599E)39 was performed by a real time PCR based allelic discrimination method, as previously described.40 Briefly, primers were designed to selectively amplify the wild‐type (T1796) and mutant (A1796) BRAF alleles. PCR amplification and melting curve analysis was performed on a Rotor‐gene 3000 (Corbett Research, NSW, Australia). Cycling conditions were as follows: 50°C for two minutes, 95°C for two minutes, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 60 seconds. After amplification, samples were subjected to a temperature ramp from 60°C to 99°C, rising 1°C each step. For wild‐type samples, single peaks were observed at 80°C and samples containing mutant alleles produced additional peaks at 85°C.

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test was used to compare the frequency of locus methylation in polyps of patients with or without hyperplastic polyposis. Loci that did not show amplification with primers for both methylated and unmethylated sequences were excluded from analysis. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Immunoexpression of MLH1

There was complete loss of expression of MLH1 in the six proximal CRCs from patient No 1, 2, 3, and 5, and these CRCs also showed high level DNA MSI (data not shown). Of 18 serrated polyps from patient No 1, seven showed loss of expression of MLH1. This included the unequivocally dysplastic subclones in four of four mixed polyps (fig 22)) and clusters of non‐dysplastic crypts in three SSAs. Among 54 serrated polyps from patient No 2, only one showed convincing loss of expression of MLH1 and this was limited to a single non‐dysplastic crypt (fig 33).). Of four serrated polyps from patient No 3, a mixed polyp showed loss of MLH1 within the adenomatous subclone and multifocal loss of MLH1 was present in an SSA. A large SSA contiguous with the CRC from patient No 4 showed normal expression of MLH1.

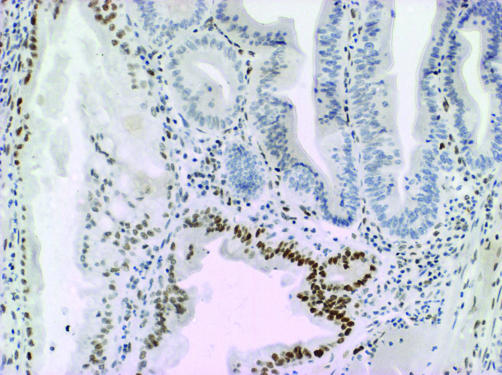

Figure 2 Loss of nuclear expression of MLH1 in adenomatous or dysplastic clone (upper right) within a sessile serrated adenoma (giving a mixed polyp) from patient No 1. ABC technique.

Loss of nuclear expression of MLH1 in adenomatous or dysplastic clone (upper right) within a sessile serrated adenoma (giving a mixed polyp) from patient No 1. ABC technique.

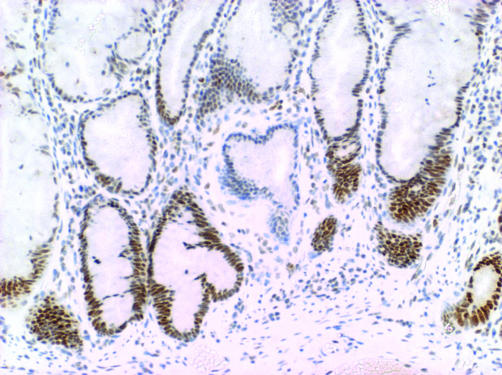

Figure 3 Loss of nuclear expression of MLH1 (possible mild residual staining) in a single crypt non‐dysplastic crypt in a sessile serrated adenoma from patient No 2. The crypt is not longitudinally sectioned but loss is clearly occurring near the crypt base. This was the only evidence of loss of expression of MLH1 in a total of 54 polyps that were tested in this patient (the colorectal cancer also showed loss of MLH1). ABC technique.

Loss of nuclear expression of MLH1 (possible mild residual staining) in a single crypt non‐dysplastic crypt in a sessile serrated adenoma from patient No 2. The crypt is not longitudinally sectioned but loss is clearly occurring near the crypt base. This was the only evidence of loss of expression of MLH1 in a total of 54 polyps that were tested in this patient (the colorectal cancer also showed loss of MLH1). ABC technique.

CpG island methylation

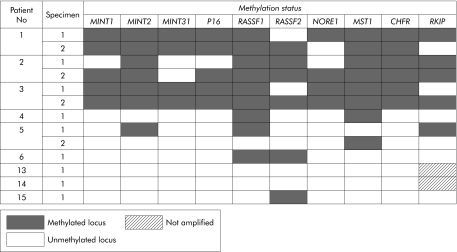

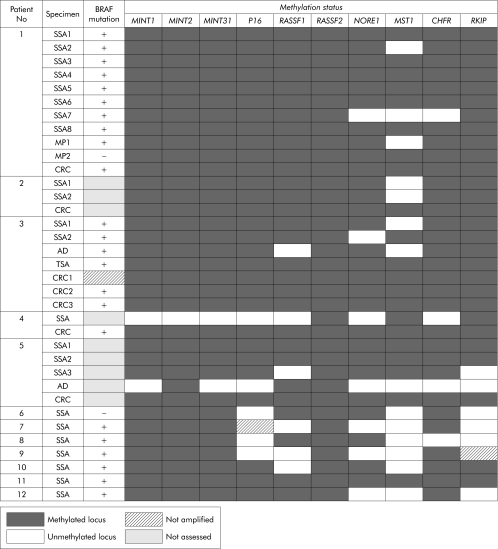

The methylation status of markers was examined in 23 SSAs, two mixed polyps, one TSA, two conventional adenomas, and seven CRCs from 12 patients (fig 44).). Markers MGMT, MLH1, FAS, and DAPK were less specific than the others in showing relatively high frequencies of methylation in normal mucosa of three subjects (No 4, 5 and 6) without HPP (data not shown). The range of locus methylation in the polyps of patient No 1–3 with HPP was 70–100% (7–10 of 10 markers) versus 30–100% (3–10 of 10 markers) in the polyps of patient No 4–12 with sporadic SSAs. The 93% methylated loci (112 of 120) demonstrated in DNA samples derived from 12 SSAs from patient No 1–3 with HPP was significantly more frequent than 73% of methylated loci (79 of 108) in 11 sporadic SSAs (patient No 4–12) (p<0.0001) (fig 44).

Figure 4 Methylation patterns in gene promoters in polyps and cancers. SSA, sessile serrated adenoma; TSA, traditional serrated adenoma; CRC, colorectal cancer.

Methylation patterns in gene promoters in polyps and cancers. SSA, sessile serrated adenoma; TSA, traditional serrated adenoma; CRC, colorectal cancer.

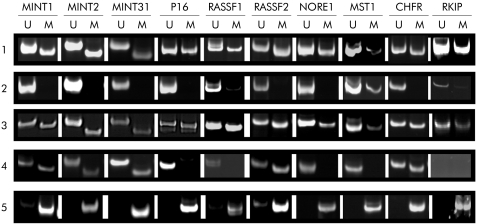

Although there was more methylation in the polyps of patients with HPP, there was considerable overlap between the patient groups (fig 44).). A more striking difference was found with respect to the frequency of methylation in normal mucosa in patients with and without HPP. While patient No 1–3 with HPP showed methylation rates of 85%, 75%, and 90% in normal colonic mucosa (17, 15, and 18 of 20 loci, respectively), we detected methylation in only 13% of loci when testing normal mucosal samples derived from patient No 4–6 and 13–15 with sporadic serrated polyps of the proximal colon (fig 55).). Examples of MSP on DNA derived from normal mucosa as well as polyps in patients with and without HPP are shown in fig 66.

Figure 6 Representative examples of methylation specific polymerase chain reaction at different loci in normal mucosa and polyps from patients with or without hyperplastic polyposis. Methylation of MINT1, 2, 31 markers, and p16, RASSF1, RASSF2, NORE1, MST1, CHFR, and RKIP was examined by methylation specific polymerase chain reaction using primers for unmethylated (U) or methylated (M) loci. (1) Normal colonic mucosa from patient No 3 (sample 2) with hyperplastic polyposis; (2) normal colon mucosa from patient No 5 (sample 2) with sporadic sessile serrated adenoma (SSA); (3) SSA from patient No 1 (sample 1) with hyperplastic polyposis; (4) SSA from patient No 9 with sporadic SSA; and (5) control methylated DNA (see materials and methods).

Representative examples of methylation specific polymerase chain reaction at different loci in normal mucosa and polyps from patients with or without hyperplastic polyposis. Methylation of MINT1, 2, 31 markers, and p16, RASSF1, RASSF2, NORE1, MST1, CHFR, and RKIP was examined by methylation specific polymerase chain reaction using primers for unmethylated (U) or methylated (M) loci. (1) Normal colonic mucosa from patient No 3 (sample 2) with hyperplastic polyposis; (2) normal colon mucosa from patient No 5 (sample 2) with sporadic sessile serrated adenoma (SSA); (3) SSA from patient No 1 (sample 1) with hyperplastic polyposis; (4) SSA from patient No 9 with sporadic SSA; and (5) control methylated DNA (see materials and methods).

BRAF mutation

Mutation of BRAF was found in 100% of SSAs (10 of 10) in patients with HPP and in 87% (7 of 8) of sporadic SSAs (fig 44).). Mutation of KRAS was found in a single mixed polyp from patient No 1 (data not shown). SSAs from patients with and without HPP were therefore well matched in terms of anatomical location and BRAF mutation.

Discussion

The role of DNA methylation or the CIMP25,44 in the evolution of CRC has been a matter of some controversy. It has been argued by some that CRCs with CIMP do not have distinct clinical, pathological, and molecular features and that DNA methylation is largely an epiphenomenon.45 However, this interpretation ignores three important groups of observations. Firstly, CIMP positive CRCs do in fact share a number of features regardless of the presence or absence of DNA MSI‐H status. These include proximal location, female predilection, mucinous and poor differentiation, and a high frequency of the serrated pathway specific BRAF mutation.46,47,48,49 Secondly, CIMP (as well as mutation of BRAF) is fully established in the putative precursor lesions of CIMP positive CRCs, namely large and proximal HPs or SSAs (see above). Thirdly, the observations that: (a) there is extensive and concordant DNA methylation across all polyps in HPP,22 (b) the condition HPP segregates within families,3,50 and (c) CRCs with BRAF mutation and/or DNA methylation occur within families,40,49,51 serve as evidence for a genetic mechanism underlying CIMP although this remains controversial.52,53 We have therefore adopted the premise that CIMP is an early pathogenic change that serves to mould colorectal tumorigenesis whether this culminates in MSI‐H or non‐MSI‐H CRCs with CIMP.

The range of DNA methylation markers used in studies of serrated polyps of the colorectum has been limited to date. Assuming that a subset of serrated polyps is characterised by a state known as the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) then it is desirable to identify an optimum panel that is both sensitive and specific for CIMP. This study employed markers that have been used extensively in studies of colorectal cancers and polyps (MINT1, MINT2, MINT31, p16, MLH1, and MGMT) as well as less widely used markers. Inhibition of apoptosis has been regarded as a pathogenic mechanism in serrated polyps20,21 but is regulated by multiple signalling pathways. We therefore reasoned that more advanced serrated polyps may be characterised by a more comprehensive inactivation of apoptosis signalling pathways through methylation of proapoptotic genes. Oncogenic activation of BRAF appears to be both proapoptotic and antiapoptotic.54RASSF1, RASSF2, and NORE1 (RASSF5) are proapoptotic genes downstream of KRAS that are known to be methylated as a component of CIMP.43,55,56,57,58,59,60,61 Silencing of these genes by methylation could therefore direct MAP kinase activation towards antiapoptotic signalling. MST1 proapoptotic kinase is activated by RASSF1/NORE1 complex31,32 although it has not been shown to be methylated previously. Augmentation of MAPK signalling may occur through inactivation of RKIP.37,38 Two further proapoptotic genes, cell surface receptor FAS and DAPK, and the mitotic checkpoint gene CHFR are all known to be methylated in colon cancer.62,63,64,65 It is possible that BRAF mutation initiates a tissue alteration (that is, a serrated polyp) when antiapoptotic signalling becomes dominant through silencing of proapoptotic genes. This could explain the close association between BRAF mutation and CIMP. However, the present study has not shown that methylation of proapoptotic genes has functional consequences with respect to gene silencing.

In order to highlight pictorially any differences among the serrated polyps with respect to DNA methylation in the preceding panel of 14 markers, we elected to exclude all markers that were methylated in normal mucosa in patients with sporadic serrated polyps. On this basis, we excluded MLH1, MGMT, FAS, and DAPK, leaving a panel of 10 markers. We and others have shown previously that some of the preceding genes, notably MGMT and MLH1, may show non‐specific methylation in normal colorectal samples.17,66 There was considerable overlap with respect to methylation in SSAs from subjects with and without HPP (fig 44).). Nevertheless, there were more instances of marker methylation in the 12 SSAs in HPP patient No 1–3 compared with 11 sporadic SSAs from patient No 4–12 (p<0.0001). This difference is not surprising given that the polyps in subjects with HPP arose within an environment of normal colonic mucosa that showed very extensive DNA methylation. However, there was no significant difference between the sets of polyps from the two groups of patients when the markers RASSF1, p16, and RKIP were excluded (p =

= 0.1) (fig 44).). It is possible that more time is required for some markers to become methylated than others. Very extensive DNA methylation was seen in all three relatively large sporadic polyps from elderly patient No 5 and in the largest (15 mm) sporadic SSA from patient No 11 (fig 44).

0.1) (fig 44).). It is possible that more time is required for some markers to become methylated than others. Very extensive DNA methylation was seen in all three relatively large sporadic polyps from elderly patient No 5 and in the largest (15 mm) sporadic SSA from patient No 11 (fig 44).

The normal mucosa in patients with HPP showed very extensive DNA methylation (fig 55).). Two previous reports have noted the finding of high level CIMP in the normal mucosa of subjects with hyperplastic polyposis.17,22 The present study extends these observations by showing concordant methylation across a large marker panel. CIMP markers generally show little or no methylation in normal colorectal mucosa and this was confirmed in the DNA samples derived from the normal colorectal mucosa of six subjects with small numbers of proximally located serrated polyps. The finding of extensive DNA methylation in normal colorectal mucosa may serve as a useful diagnostic biomarker for high cancer risk forms of HPP. However, there is a need to confirm these findings in additional subjects with HPP and this should include the detailed mapping of the extent of methylation in different regions of the colon. Given the predilection for CIMP positive CRC to occur in the proximal colon, it is possible that DNA hypermethylation would be more extensive proximally. The present findings should be distinguished from the increased methylation restricted to MGMT that has been demonstrated as a field change in normal colorectal mucosa from subjects in whom CRCs show MGMT methylation.67

An explanation for the finding of extensive DNA methylation in normal mucosa in HPP can only be speculative but nevertheless warrants consideration. As noted above, CRCs with CIMP have been linked with family history in two cancer family clinic based studies40,51 and one large population based study.49 The findings in these three studies support the possibility of genetic predisposition to aberrant DNA methylation. The population based study was large (911 subjects) and bias free. Patients were stratified on the basis of BRAF mutation but the authors demonstrated a very strong correlation between BRAF mutation and CIMP, regardless of whether CRCs were DNA microsatellite stable or MSI‐H.49 In subjects with microsatellite stable CRCs, the odds ratio for a positive family history when comparing BRAF mutation positive and BRAF wild‐type groups was 4.23 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.65–10.84). In the case of MSI‐H CRCs, the odds ratio for a positive family history was only 0.64 (95% CI 0.18–2.19) for subjects with BRAF mutation positive versus BRAF wild‐type CRCs. However, one third of subjects with BRAF wild‐type/MSI‐H CRCs were aged less than 55 years and a proportion would be expected to have Lynch syndrome.49

In a separate study using the same population, the authors demonstrated a weaker association between CIMP and family history.53 However, they employed a very broad definition of CIMP (two or more of five markers methylated) to the extent that less than one third of CIMP positive cancers had BRAF mutation. Using a similarly broad definition of CIMP, a hospital based study found no link between CIMP positive CRC and family history.52 However, this study is difficult to evaluate because it excluded families with “hereditary non‐polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC)” without stating how HNPCC was defined. Families may meet the Amsterdam criteria without having HNPCC/Lynch syndrome. While there is no consensus in the literature, there is good evidence for the heritability of CIMP and the contrary evidence can be explained by limitations in study design.

HPP is associated with CIMP positive polyps and CRCs but is an extremely uncommon condition. Nevertheless, instances of HPP have been documented within the setting of CRC families in which cancers show BRAF mutation and/or DNA methylation40 and in siblings.50 It is conceivable that the usual CIMP positive CRCs develop through a “two hit” mechanism whereby one mutant copy of a gene that is implicated in the regulation of DNA methylation is inherited, while the wild‐type allele is inactivated at the somatic level. The widespread methylation of normal mucosa found in HPP might then occur in subjects who have inherited two copies of such a mutated gene. On the basis of the above, HPP may serve as an important genetic model for CIMP. These suggestions remain highly speculative and do not preclude a role for environmental factors in the aetiology of both DNA methylation and HPP. Age and inflammatory bowel disease are known to influence DNA methylation in colorectal mucosa.68

The phenotypes in patient No 1 and 3 are very similar. Both patients had only moderate numbers of serrated polyps but a high proportion of these showed dysplasia (mixed polyps or traditional serrated adenomas) and/or loss of expression of MLH1. In contrast, patient No 2 had very large numbers of serrated polyps, including many typical hyperplastic polyps. Only one polyp (a mixed polyp) showed mild dysplasia. In addition, loss of MLH1 expression was confined to a single non‐dysplastic crypt in a sessile serrated adenoma. While all three subjects showed extensive DNA methylation in normal colorectal mucosa, it is possible that methylation leading to loss of expression of MLH1 is influenced by an additional partly independent mechanism. This would explain why some patients with hyperplastic polyposis, such as patient No 3 and others reported in the literature,8,69 develop multiple synchronous CRCs that may be MSI‐H.

In summary, we have documented the finding of extensive DNA methylation in samples of normal mucosa from the proximal colon of subjects with HPP and suggest that there may be a genetic basis for this observation. Some of the observed heterogeneity within HPP may be explained by differing propensities for MLH1 inactivation that may be due to mechanisms that are partly independent of a general predisposition to DNA methylation. Finally, observations relating to methylation of multiple proapoptotic genes provide an explanation for the synergy between DNA methylation and mutation of BRAF although this will need to be confirmed by functional studies.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Grant No MOP‐67206. The specimen for patient No 4 was kindly provided by Professor A Paterson, School of Pathology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. We thank H Minassian for technical support.

Abbreviations

HP - hyperplastic polyp

HPP - hyperplastic polyposis

SSA - sessile serrated adenoma

TSA - traditional serrated adenoma

HNPCC - hereditary non‐polyposis colorectal cancer

CRC - colorectal cancer

MSI - microsatellite instability

CIMP - CpG island methylator phenotype

PCR - polymerase chain reaction

MSP - methylation specific polymerase chain reaction

MAPK - mitogen activated protein kinase

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

Articles from Gut are provided here courtesy of BMJ Publishing Group

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2005.082859

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc1856423?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1136/gut.2005.082859

Article citations

Transcription factor expression repertoire basis for epigenetic and transcriptional subtypes of colorectal cancers.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 120(31):e2301536120, 24 Jul 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37487069 | PMCID: PMC10401032

Understanding Mechanisms of RKIP Regulation to Improve the Development of New Diagnostic Tools.

Cancers (Basel), 14(20):5070, 17 Oct 2022

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 36291854 | PMCID: PMC9600137

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Epigenome-Wide DNA Methylation Profiling of Normal Mucosa Reveals HLA-F Hypermethylation as a Biomarker Candidate for Serrated Polyposis Syndrome.

J Mol Diagn, 24(6):674-686, 18 Apr 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35447336 | PMCID: PMC9228001

Isolation of endogenous cytosolic DNA from cultured cells.

STAR Protoc, 3(1):101165, 05 Feb 2022

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 35535161 | PMCID: PMC9076957

A Stochastic Binary Model for the Regulation of Gene Expression to Investigate Responses to Gene Therapy.

Cancers (Basel), 14(3):633, 27 Jan 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 35158901 | PMCID: PMC8833822

Go to all (92) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Hyperplastic/serrated polyposis in inflammatory bowel disease: a case series of a previously undescribed entity.

Am J Surg Pathol, 32(2):296-303, 01 Feb 2008

Cited by: 25 articles | PMID: 18223333

[Immunophenotypes and gene mutations in colorectal precancerous lesions and adenocarcinoma].

Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi, 42(10):655-659, 01 Oct 2013

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 24433726

Serrated polyps of the large intestine: a molecular study comparing sessile serrated adenomas and hyperplastic polyps.

Histopathology, 55(2):206-213, 01 Aug 2009

Cited by: 37 articles | PMID: 19694828

Molecular and histologic considerations in the assessment of serrated polyps.

Arch Pathol Lab Med, 139(6):730-741, 01 Jun 2015

Cited by: 23 articles | PMID: 26030242

Review