Abstract

Free full text

Transmission of Equine Influenza Virus to English Foxhounds

Abstract

We retrospectively demonstrated that an outbreak of severe respiratory disease in a pack of English foxhounds in the United Kingdom in September 2002 was caused by an equine influenza A virus (H3N8). We also demonstrated that canine respiratory tissue possesses the relevant receptors for infection with equine influenza virus.

Influenza A viruses are divided into subtypes according to the serologic reactivity of the surface glycoproteins hemagglutinin (H1–H16) and neuraminidase (N1–N9). Aquatic birds are regarded as the natural reservoir for influenza A viruses; a few mammalian hosts are infected by a limited number of virus subtypes. The first evidence of the H3N8 subtype, which currently circulates in horses, crossing species barriers was reported after an outbreak of respiratory disease among racing greyhounds in Florida in 2004. Isolation of virus from 1 case and detection of specific antibodies in other cases identified equine influenza virus as the cause of the outbreak (1). This information led us to reexamine an outbreak of severe respiratory disease that occurred in a pack of 92 English foxhounds in the United Kingdom in September 2002.

The Study

The outbreak was signaled by a sudden onset of coughing. Some hounds became lethargic and weak; in some, these signs progressed to loss of consciousness. One hound died and 6 were euthanized. Postmortem examination of the hound that died (case 1) and 1 that was euthanized (case 2) showed subacute broncho-interstitial pneumonia; virus was suspected as the cause. When they were puppies (≈8 weeks of age), the hounds had been inoculated with commercially available vaccines against the major canine respiratory and enteric viruses. Postmortem tissue samples submitted to a canine infectious diseases laboratory were negative for known canine viral pathogens (e.g., canine herpesvirus, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus). The diagnosis as to the cause of the pneumonia, returned in 2002, was “unknown, suspected viral etiology.”

In January and March 2005, serum samples were obtained from the hounds affected by the respiratory disease outbreak in 2002 (pack 1). Serum samples were obtained from another 3 packs of foxhounds in the same region of the United Kingdom during December 2004 through February 2005. Samples were collected from 31–33 hounds (equivalent numbers of males and females) in each pack, ranging in age from 9 months to 9 years. The serum was screened for antibodies by using the single radial hemolysis assay (2). None of the samples contained antibodies to the strains that were included in the assay to control for nonspecific reactivity: equine H7N7 subtype strain A/equine/Prague/56 and the human influenza virus strain A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1). Antibodies to the H3N8 subtype strains A/equine/Newmarket/1/93 and A/equine/Newmarket/2/93 were, however, detected in 9 of the samples obtained during the first visit to pack 1 (Table). Of these, 8 were from hounds that had survived the outbreak in 2002; however, 1 was from a hound (no. 22) born after the outbreak in another part of the United Kingdom, which suggests that the 2002 outbreak might not have been the only incident of equine influenza to have infected hounds in the United Kingdom. Another 3 positive serum samples were obtained during a second visit to pack 1, and a repeat sample from hound no. 22 again had positive results. The specificity of the antibodies for equine influenza A (H3N8) strains was confirmed by hemagglutination inhibition assays that included human influenza (H3N2) strain A/Scotland/74 (data not shown).

Table

| Hound no. | Date sampled, 2005 | Sex | Year born | Influenza virus strain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/equine/Newmarket/1/93 | A/equine/Newmarket/2/93 | ||||

| 1 | Jan 21 | F | 2002 | <10 | <10 |

| 2 | Jan 21 | M | 2002 | 48 | <10 |

| 2 | Mar 9 | 46 | <10 | ||

| 3 | Jan 21 | F | 2001 | <10 | <10 |

| 4 | Jan 21 | F | 2001 | <10 | <10 |

| 5 | Jan 21 | F | 2002 | 47 | 21 |

| 5 | Mar 9 | 64 | 36 | ||

| 6 | Jan 21 | M | 2002 | <10 | <10 |

| 7 | Jan 21 | M | 1999 | <10 | <10 |

| 8 | Jan 21 | M | 2001 | <10 | <10 |

| 9 | Jan 21 | M | 1998 | 43 | <10 |

| 10 | Jan 21 | M | 1999 | 76 | 54 |

| 11 | Jan 21 | M | 1999 | <10 | <10 |

| 12 | Jan 21 | F | 2002 | 55 | 28 |

| 13 | Jan 21 | M | 1997 | <10 | <10 |

| 14 | Jan 21 | F | 2003 | <10 | <10 |

| 15 | Jan 21 | M | 2001 | 51 | 18 |

| 16 | Jan 21 | M | 1999 | <10 | <10 |

| 17 | Jan 21 | F | 2002 | <10 | <10 |

| 18 | Jan 21 | M | 2002 | 13 | 11 |

| 19 | Jan 21 | M | 1999 | <10 | <10 |

| 20 | Jan 21 | M | 2001 | <10 | <10 |

| 20 | Mar 9 | <10 | <10 | ||

| 21 | Jan 21 | F | 2001 | <10 | <10 |

| 22 | Jan 21 | M | 2003 | 52 | 25 |

| 22 | Mar 9 | 71 | 40 | ||

| 23 | Jan 21 | M | 2001 | 51 | 27 |

| 23 | Mar 9 | 55 | 20 | ||

| 24 | Jan 21 | F | 1999 | <10 | <10 |

| 24 | Mar 9 | <10 | <10 | ||

| 25 | Jan 21 | F | 2002 | <10 | <10 |

| 26 | Jan 21 | F | 2000 | <10 | <10 |

| 26 | Mar 9 | <10 | <10 | ||

| 27 | Jan 21 | F | 1999 | <10 | <10 |

| 28 | Jan 21 | F | 2000 | <10 | <10 |

| 29 | Jan 21 | F | 2002 | <10 | <10 |

| 30 | Jan 21 | M | 2002 | <10 | <10 |

| 30 | Mar 9 | <10 | <10 | ||

| 31 | Jan 21 | F | 1998 | <10 | <10 |

| 32 | Jan 21 | F | 1999 | <10 | <10 |

| 33 | Jan 21 | M | 2003 | <10 | <10 |

| 34 | Mar 9 | NK | NK | 14 | <10 |

| 35 | Mar 9 | NK | NK | <10 | <10 |

| 36 | Mar 9 | NK | NK | 99 | 54 |

| 37 | Mar 9 | NK | NK | <10 | <10 |

| 38 | Mar 9 | NK | NK | <10 | <10 |

| 39 | Mar 9 | NK | NK | <10 | <10 |

| 40 | Mar 9 | NK | NK | 83 | 33 |

*Measured by single radial hemolysis (mm2) in serum samples. NK, not known.

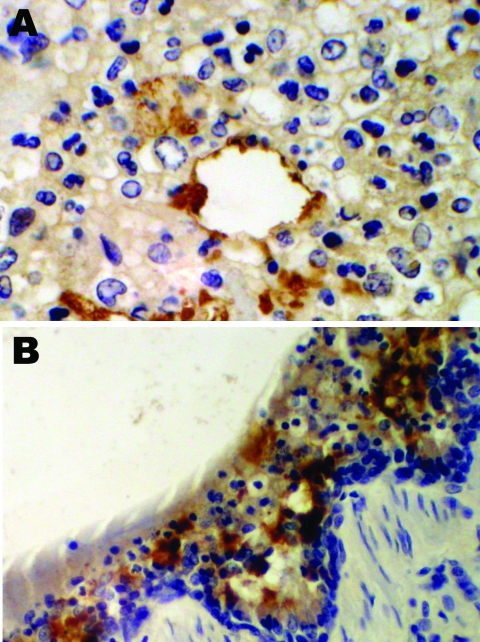

An immunohistochemical test to detect influenza A virus that used equine influenza–specific rabbit polyclonal antiserum was applied to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues from the 2 hounds that were examined postmortem in 2002 (3). Immunostaining of lung tissue showed positive staining in areas of pneumonic change; infected cells had the morphology of epithelial cells and macrophages (Figure 1). Immunostaining of visceral tissues (lung, liver, spleen, myocardium, intestine, pancreas, and oropharynx) was negative.

Immunohistochemical staining for equine influenza A virus (brown stain) in sections of respiratory tissue from English foxhounds involved in 2002 respiratory disease outbreak, United Kingdom. A) Case 1, showing focal staining of an apparently necrotic bronchiole in an area of pneumonia; magnification x100. B) Case 2, showing a large amount of staining throughout the epithelium and inflammatory cells present in the brush border; magnification x200; hematoxylin counterstain.

Deparaffinization of the FFPE lung tissue from the 2 hounds was performed as described previously (4) with a few modifications. RNA was extracted from the sample pellets obtained using the QIAamp viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Ten different primer pairs designed to amplify short (<250-bp) products from the matrix hemagluttinin and neuraminidase genes were used (details available from the authors on request). Reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) was carried out by using the QIAGEN OneStep RT-PCR Kit. Only 1 primer pair (forward: 5′-AGGCAGGATAAGCATATACT-3′ and reverse: 5′-GTGCATCTGATCTCATTACA-3′, amplifying nucleotides 735–871 of the hemagglutinin gene) yielded an amplification product, which was purified by using PCR Kleen Spin Columns (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and sequenced by using the BigDye Terminator v1.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). A BLAST search with the 74-bp nt sequence obtained from this amplicon confirmed that the virus shared 100% identity with the equine influenza (H3N8) strains Newmarket/1/93 (5) and Newmarket/5/03 (6). This region contains 2 phylogenetically informative sites. Lysine at position 261 indicates that the virus belongs to the American lineage (5); this is supported by the presence of isoleucine at position 242 because all European lineage strains isolated since 1998 have valine at 242.

Conclusions

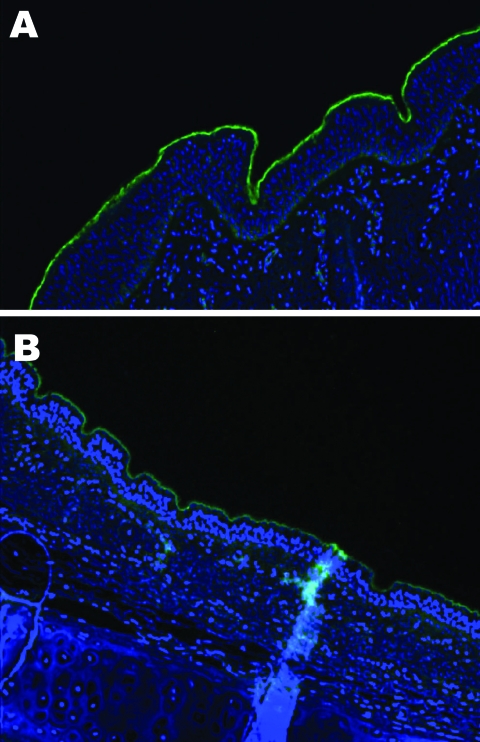

An important factor in interspecies transmission is the ability of the hemagglutinin protein of the virus to bind to certain receptors on the host cells before the virus is internalized. Although all influenza A viruses recognize cell surface oligosaccharides with a terminal sialic acid, their receptor specificity varies; it is thought that species-specific differences in the distribution of linkages on respiratory epithelial cells influences the ability of influenza A viruses to transmit between species. Respiratory tract tissue samples were obtained within 2–4 hours of death from a horse and a greyhound, each euthanized for reasons other than this study, and rinsed extensively to remove surface mucous. The tissues were stained by immunofluorescence by using the lectins Sambucus nigra (SNA, specific for SAα2,6 galactose(Gal)/N-acetylgalactosaminide) and Maackia amurensis (MAA, specific for SAα2,3) as previously described (7). The MAA lectin bound strongly to the equine tracheal epithelium (Figure 2, panel A), which confirms the finding that the NeuAc2,3Gal linkage preferentially bound by equine influenza viruses is found on sialyloligosaccharides in the equine trachea (7). The MAA lectin also bound strongly to the canine respiratory epithelium (Figure 2, panel B) at all levels of the respiratory tract examined (distal, medial and proximal trachea; primary and secondary bronchi), which suggests that receptors with the required linkage for recognition by equine influenza virus are available on canine respiratory epithelial cells, although further subtle differences in receptor specificity may exist. The SNA lectin, specific for SAα2,6Gal, which did not bind to the equine tracheal epithelium, showed some binding to the canine epithelium (data not shown).

Lectin staining for α2,3 sialic acid linkages on A) equine trachea and B) canine trachea; magnification x200; cell nuclei counterstained with Hoechst 33342 solution.

Because the hounds infected in 2002 were housed near horses, it is possible that the virus was transmitted from infected horses by the usual (aerosol) route. However, during the week before onset of clinical signs, the hounds had been fed the meat of 2 recently euthanized horses from independent sources. That viral antigen expression was confined to the lungs indicates a respiratory rather than oral route of infection. It is possible that eating respiratory tissue from an infected horse led to inhalation of sufficient virus particles to initiate a respiratory infection. Consumption of infected bird carcasses has been implicated in the transmission of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus of the H5N1 subtype to tigers and leopards (8) and a dog (9) and was demonstrated experimentally by feeding virus-infected chicks to domestic cats (10).

Although the mechanism remains unclear, we have demonstrated transmission of equine influenza virus to dogs in the United Kingdom, independent of that in the United States. We have also shown that canine respiratory tissue displays the relevant receptors for infection with equine influenza virus.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the referring veterinary surgeon; the owners and handlers of the foxhound packs; the Canine Virus Unit, University of Glasgow; and Greg Dowd, who performed the immunostaining.

This work was supported by the Animal Health Trust. Studies on receptor specificity were funded by a British Biological Sciences Research Council grant (S18874). Battersea Dogs and Cats Home, Dogs Trust, and the Kennel Club provided generous funding for the serologic surveys conducted to detect equine influenza virus antibodies in canine serum samples.

Biography

Dr Daly recently joined the University of Liverpool’s Virus Brain Infections Group. Her research interests are zoonotic viral infections; she is currently conducting research on the immunopathology of Japanese encephalitis virus.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Daly JM, Blunden AS, MacRae S, Miller J, Bowman SJ, Kolodziejek J, et al. Transmission of equine influenza virus to English foxhounds. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2008 Mar [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/14/3/461.htm

References

Articles from Emerging Infectious Diseases are provided here courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.3201/eid1403.070643

Article citations

Adaptation potential of H3N8 canine influenza virus in human respiratory cells.

Sci Rep, 14(1):18750, 13 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39138310 | PMCID: PMC11322661

Exploring Potential Intermediates in the Cross-Species Transmission of Influenza A Virus to Humans.

Viruses, 16(7):1129, 14 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39066291 | PMCID: PMC11281536

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Understanding the divergent evolution and epidemiology of H3N8 influenza viruses in dogs and horses.

Virus Evol, 9(2):vead052, 18 Aug 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37692894 | PMCID: PMC10484056

Interactions of Equine Viruses with the Host Kinase Machinery and Implications for One Health and Human Disease.

Viruses, 15(5):1163, 13 May 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37243249 | PMCID: PMC10221139

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Zoonotic Animal Influenza Virus and Potential Mixing Vessel Hosts.

Viruses, 15(4):980, 16 Apr 2023

Cited by: 19 articles | PMID: 37112960 | PMCID: PMC10145017

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (95) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Infection of dogs with equine influenza virus: evidence for transmission from horses during the Australian outbreak.

Aust Vet J, 89 Suppl 1:27-28, 01 Jul 2011

Cited by: 28 articles | PMID: 21711279

Equine influenza: a review of an unpredictable virus.

Vet J, 189(1):7-14, 03 Aug 2010

Cited by: 41 articles | PMID: 20685140

Review

Influenza virus transmission from horses to dogs, Australia.

Emerg Infect Dis, 16(4):699-702, 01 Apr 2010

Cited by: 51 articles | PMID: 20350392 | PMCID: PMC3321956

Canine influenza.

Compend Contin Educ Vet, 32(6):E1-9; quiz E9, 01 Jun 2010

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 20949424

Review

*

*