Abstract

Free full text

Type I Interferon Induced by Adenovirus Serotypes 28 and 35 Has Multiple Effects on T Cell Immunogenicity

Abstract

Recombinant adenovirus vectors (rAds) are being investigated as vaccine delivery vehicles in pre-clinical and clinical studies. rAds constructed from different serotypes differ in receptor usage, tropism, and ability to activate cells, aspects of which likely contribute to their different immunogenicity profiles. Here, we compared the infectivity and cell stimulatory capacity of rAd serotype 5 (rAd5), rAd28 and rAd35 in association with their respective immunogenicity profiles. We found that rAd28 and rAd35 infected, and led to the in vitro maturation and activation, of both human and mouse dendritic cells (DCs) more efficiently compared to rAd5. In stark contrast to rAd5, rAd28 and rAd35 induced production of interferon alpha (IFNα) and stimulated interferon-related intracellular pathways. However, the in vivo immunogenicity of rAd28 and rAd35 was significantly lower than that of rAd5. Deletion of IFNα signaling during vaccination with rAd28 and rAd35 vectors increased the magnitude of the insert-specific T-cell response to levels induced by vaccination with rAd5 vector. The negative impact of IFNα signaling on the magnitude of the T cell response could be overcome by increasing the vaccine dose, which was also associated with greater polyfunctionality and a more favorable long-term memory phenotype of the CD8 T cell response in the presence of IFNα signaling. Taken together, our results demonstrate that rAd-induced IFNα production has multiple effects on T cell immunogenicity, the understanding of which should be considered in the design of rAd vaccine vectors.

Introduction

Recombinant adenovirus vectors (rAd) have proven to be very effective at inducing antigen-specific, polyfunctional T cell responses (1, 2). Recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 (rAd5)-based vectors have been extensively studied as potential HIV/AIDS vaccines and tested in phase I and phase II clinical trials (3). The results of these trials, in conjunction with studies in rhesus macaques, have revealed that pre-existing immunity against the rAd5 vector can reduce the immunogenicity of the vaccine and limit the memory response to the HIV-antigen insert (4). Since 40–80% of the world’s population is seropositive for Ad5, the usefulness of a rAd5-based vaccine may be compromised (5–13). To circumvent preexisting immunity, alternative adenovirus vectors from serotypes with much lower seroprevalence, such as Ad28 and Ad35, are under development (11–14). However, some vectors constructed from low-seroprevalence adenoviruses have shown poor immunogenicity in vivo (13). This presents a paradox whereby rAd5, which induces a good immune response, is limited due to widespread preexisting immunity while rAd28 and rAd35, to which there is low pre-existing immunity, are inherently less immunogenic. The reasons for these differences in immunogenicity are poorly understood, yet critical for the future development of vaccines based upon these adenoviral serotypes.

The different serotypes of rAds differ in receptor usage, cell tropism, and ability to induce cell activation (1, 15, 16). Specifically, rAd35 but not rAd5 induces maturation of DCs and high IFNα production, both of which are important components of innate immunity (1). Other models have shown that differences in innate immunity can have important effects on the magnitude (17–19), Th1/Th2 distribution (20–22), and central/effector memory distribution (23–25) of the subsequent adaptive immune response. Specifically, IFNα, a key cytokine involved in the innate immune response and the establishment of the antiviral state (26–29), has been shown to promote the maturation (30), proliferation (18, 31), survival (32), differentiation (18, 33), and effector function (34) of CD8 T cells. Paradoxically, IFNα has also been shown to suppress the proliferation (35, 36), and limit the survival (37), of antigen-specific CD8 T cells depending on the timing, level, and duration of its production. There is little information on how rAd-induced IFNα influences the development of the insert-specific adaptive immune response.

Here we show that rAd28 and rAd35, but not rAd5, induce the production of IFNα in vitro in cells of both human and murine origin as well as in vivo in mice. The induction of IFNα by rAd28 and rAd35 was associated with efficient infection and phenotypic maturation of both human and mouse dendritic cells (DCs). We further demonstrate that IFNα/® receptor knockout (IFNabr−/−) mice vaccinated with rAd28 and rAd35 generated more antigen-specific T cells than did similarly vaccinated wildtype mice. This difference was not observed in mice immunized with rAd5. IFNα signaling during immunization with rAd28 and rAd35 was also found to skew the central/effector memory distribution and functional profile of the CD8 T cell response. Finally, we show that the induction of IFNα limits insert expression by rAd28 and rAd35, providing a possible mechanism for the observed effects on immunogenicity.

Materials and Methods

PBMC isolation

Human PBMCs from normal, healthy donors were obtained by automated leukapheresis and isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Plaque PLUS (GE Healthcare). PBMCs were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 1% streptomycin and penicillin (Invitrogen), and 10% FCS (Gibco) at a density of 1×106 cells/ml. Signed informed consent was obtained from all donors in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the study was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Board.

Isolation of primary DC subsets from blood

The sorting processes for direct isolation of CD11c+ myeloid DCs (mDCs) and CD123+ plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) from blood have been described previously (1, 38, 39). Briefly, PBMCs collected from healthy blood donors were further enriched for monocytes/DCs by semiautomatic counterflow centrifugation (Elutra Cell Separation System). CD1c and BDCA4 isolation kits (Mitenyi Biotec) were used in conjunction with an AutoMACS magnetic cell sorter (Miltenyi Biotec) to isolate mDCs and pDCs, yielding highly enriched populations for both (>85%) (1). Flow cytometry revealed the contaminating cells to be CD14+. For microarray experiments, the respective DC populations were further purified into CD11c+CD14− populations (for mDCs) and CD123+CD14− populations (for pDCs) using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). This process yielded highly pure cell populations (>99.9%). Sorted cell populations were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% streptomycin and penicillin, and 10% FCS at a density of 1×106 cells/ml.

Construction of rAds

Replication-deficient rAd5, rAd28, and rAd35 vectors expressing SIV Gag or eGFP were provided by GenVec Inc. The construction of the E1/E3/E4-deleted rAd5 and rAd35 (40, 41) and the E1-deleted rAd28 (14) has been described previously.

rAd infection and stimulation

Cells were exposed to multiple MOIs of rAd5, rAd28, or rAd35 encoding for eGFP for 24 hours. TLR7/8-ligand (1 μg/ml) (3M) was used to induce DC maturation.

CD46 blocking

Isolated mDCs were treated with anti-CD46 neutralizing antibody (clone M177, Hycult Biotechnologies) or an isotype-matched control (clone P3, eBiosciences) for 15 minutes at room temperature prior to rAd exposure.

DC infection and phenotype assessment by polychromatic flow cytometry

Isolated and rAd-infected DCs were washed with PBS and incubated with a viability marker (ViViD; Molecular Probes) and FcR blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec) for 10 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then washed with PBS containing 0.5% BSA and stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies to CD11c, CD123, CD14, and CD80 for 15 minutes at room temperature. Similarly, PBMCs were washed and incubated with ViViD and FcR blocking reagent before the cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies to CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD19, CD56, and HLA-DR for 15 minutes at room temperature. All samples were analyzed using a LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo version 9.3.2 (Tree Star).

Measurements of human and mouse IFNα release

The supernatants from human and mouse DC cultures as well as serum collected from mice 6 hours post-immunization were analyzed using VeriKine Human or Mouse Interferon-Alpha ELISA Kits (PBL Laboratories), respectively, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Mircoarrays

Purified DC populations were either left unexposed or incubated with rAd5, rAd28, rAd35, or TLR7/8-ligand for 24 hours. The cells were then harvested and placed at −80°C in RLT buffer. Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Micro Kits (QIAgen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and checked for quantity and quality using a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and an Experion Automated Electrophoresis System. Samples with an RQI classification ≥7.0 were normalized at 150 ng for tRNA input and amplified using Illumina TotalPrep RNA amplification kits (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Microarray analysis was conducted using 750 ng of biotinylated cRNA hybridized to Human RefSeq-8 V3 BeadChips (Illumina) at 58°C for 20 hours. The hybridized BeadChips were washed, blocked, stained and scanned according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The arrays were scanned using an Illumina BeadStation 500GX scanner and quantified using GenomeStudio software (Illumina). Analysis of the GenomeStudio output data was conducted using the R statistical language (R Development Core Team) (42) and various software packages from Bioconductor (43). Quantile normalization was applied, followed by a log2 transformation. The LIMMA package from Bioconductor (44) was used to fit a single linear model to each probe and to perform (moderated) t-tests on the incubation effects for a given DC population. Specifically, the fitted linear model assigned mock samples as DC population-specific and individual-specific intercepts (multivariate analog of paired-samples). The list of interferon-regulated genes (IRGs) employed to filter genes was defined in previous work (45, 46). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; Ingenuity Systems, www.ingenuity.com) was used to test for over-representation of canonical pathways in the lists of genes differentially expressed upon incubation. For this purpose, statistical significance for gene differential expression was defined as |FC|>1.5, P<0.01 at FDR<30%, while statistical significance for over-representation (Fisher’s exact test) was defined at FDR<5%. The expected proportions of false positives (FDR) were estimated from the unadjusted P values using the Benjamini and Hochberg method. The microarray data are available through the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), accession number: GSE37128.

Mice

C57BL/6 mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory were maintained in the Vaccine Research Center Animal Care Unit. IFNα/β receptor knockout (IFNabr−/−) mice were provided by Brian Kelsall (NIH), and bred and maintained in the animal facility at the NIH. All experiments were conducted following the guidelines of, and with approval from, the Vaccine Research Center Animal Care and Use Committee.

Murine DC isolation

Splenocytes were harvested from wildtype mice. Total DCs were isolated to >50% purity using a pan-DC microbead kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and an AutoMACS cell sorter according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Immunizations

Mice were immunized with rAd5, rAd28, or rAd35 in a total volume of 50μL by subcutaneous injection in each of the hind footpads.

Polychromatic flow cytometric analysis of SIV Gag-specific responses

Blood was collected from mice into heparin-containing tubes and treated for 3 minutes at room temperature with ACK buffer (Lonza) to lyse the red blood cells. The cells were then pelleted and washed twice with PBS. Cells were transferred to 96-well plates and incubated with a viability marker (OrViD; Molecular Probes) and FcR blocking reagent for 10 minutes at room temperature. After a further wash with PBS containing 0.5% BSA, cells were stained for 15 minutes at room temperature with fluorescently labeled AL11 (AAVKNWMTQTL) SIV Gag tetramer, constructed around H2-Db using protocols described previously (47), and antibodies to CD8, CD27, CD44, CD62L, and CD127. After fixation, cells were analyzed using an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Viable CD8 T cells were selected within a small lymphocyte gate based on CD8 expression and lack of staining with OrViD. The fraction of viable CD8 T cells binding the AL11 tetramer was used to determine the percentage of SIV Gag-specific CD8 T cells. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo version 9.3.2.

Intracellular cytokine staining

Splenocytes isolated from mice 82 days after immunization were transferred to a 96-well plate. Cells were exposed to AL11 peptide for 30 minutes and treated with brefeldin A (10 μg/ml; Sigma Aldrich) and monensin (0.7 μg/ml; eBiosciences) for 6 hours. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and incubated with a viability marker (ViViD) for 10 minutes at room temperature. After a further wash in PBS containing 0.5% BSA, cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies to CD4 and CD8 for 15 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then permeabilized with Fix/Perm (BD Biosciences) for 20 minutes at room temperature, washed with Perm/Wash (BD Biosciences) and stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies to CD3, IFNγ, IL2, and TNF for a further 20 mins at room temperature. Cells were analyzed using an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Viable CD8 T cells were selected using the viability marker, a small lymphocyte gate, and expression of CD3 and CD8. Frequencies of cytokine producing cells were calculated within the viable CD3+ CD8+ T cell populations. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo version 9.3.2.

Exogenous rIFNα treatment

5ng/mL of exogenous mouse rIFNα (PBL Interferon Source) was added to cultures immediately before infection with the rAd vectors.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test or the Mann-Whitney U-test with GraphPad Prism version 5.0c software (GraphPad Software). Analysis and presentation of distributions was performed using SPICE version 5.1, downloaded from http://exon.niaid.nih.gov (48). Comparison of distributions was performed using a Student’s T-test and a partial permutation test as described previously (48). Error bars shown represent standard deviation in all cases.

Results

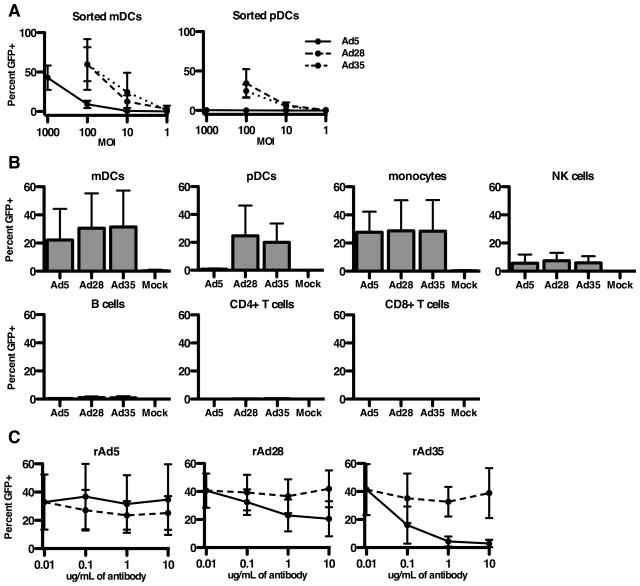

Infectivity of rAd5, rAd28 and rAd35 vectors

We compared the infectivity of rAd5, rAd28 and rAd35 on isolated human DCs. rAd28 and rAd35 efficiently infected mDCs (59%±21 and 59%±32 eGFP+ cells at MOI 100, respectively). In contrast, rAd5 required a 10-fold higher virus inoculum to show similar infectivity (43%±15 eGFP+ cells at MOI 1000) (Figure 1A). Moreover, rAd28 and rAd35 infected over 25% of pDCs at MOI 100, whereas rAd5 exposure did not show detectable infection at any MOI tested. This disparity between rAd5 and rAd35 infection of DCs is in line with prior observations (1, 49, 50). To test the ability of rAd5, rAd28, and rAd35 to infect other human immune cells, we performed similar infections on unfractioned PBMCs. At an MOI of 100, rAd28 and rAd35 infected mDCs (31%±24, 31%±26), pDCs (24%±21, 20%±13), monocytes (28%±21, 28%±22), and NK cells (7%±5, 6%±5) (Figure 1B). A 10-fold greater dose (MOI 1000) of rAd5 was needed to infect mDCs (22%±20), monocytes (27%±14), and NK cells (6%±5) at a similar level. As expected, rAd5 did not infect pDCs. The rate of infection of B cells, CD4 T cells, and CD8 T cells was negligible with all rAd vectors.

(A) Infection frequencies of mDCs and pDCs treated with rAd5 vector, rAd28 vector, or rAd35 vector (n=5). (B) Infection frequencies of mDCs, pDCs, monocytes, NK cells, B cells, CD4 T cells, and CD8 T cells from PBMCs treated with rAd5 vector (MOI1000), rAd28 vector (MOI100), or rAd35 vector (MOI100), each with an uninfected control (n=8). (C) Infection frequencies of mDCs treated with anti-CD46 antibody (solid line) or a matched isotype control (dashed line) (n=4).

Receptor usage

The entry receptors used by Ad5 and Ad35 are CAR and CD46, respectively (1). The entry receptor for Ad28 is less clear. An anti-CD46 antibody was unable to block infection of mDCs by rAd5 but efficiently blocked infection by rAd35 (Figure 1C). In contrast, the anti-CD46 antibody only modestly reduced infection of mDCs by rAd28, and only at high concentrations. The isotype-matched control antibody showed no reduction in infectivity at any dose for any vector. While we cannot rule out that Ad28 may be using CD46 as one of several cellular receptors, we can conclude that Ad28 is not as dependent as Ad35 on CD46 for infection of human mDCs.

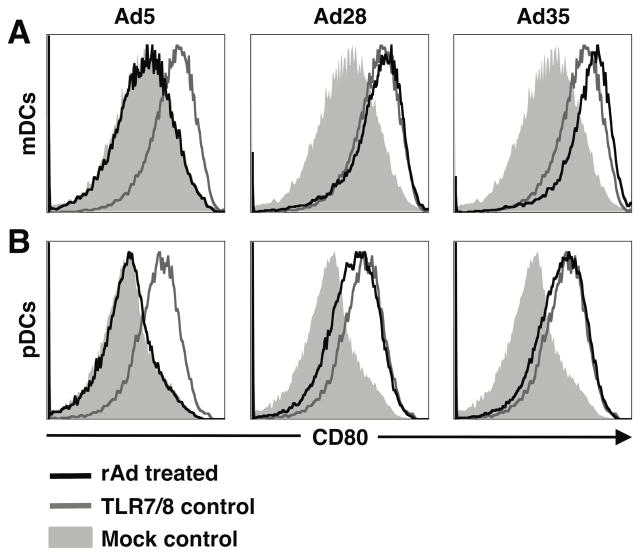

rAd vector-induced maturation

To determine the degree of maturation and activation induced by rAd vectors, we analyzed co-stimulatory receptor CD80 expression on mDCs (Figure 2A) and pDCs (Figure 2B) 24 hours post-infection. In both mDCs and pDCs exposed to rAd28 and rAd35, CD80 expression was upregulated similar to that induced by toll-like receptor (TLR) stimulation. In contrast, expression of CD80 in either of the DC subsets exposed to rAd5 was unchanged compared to the uninfected control.

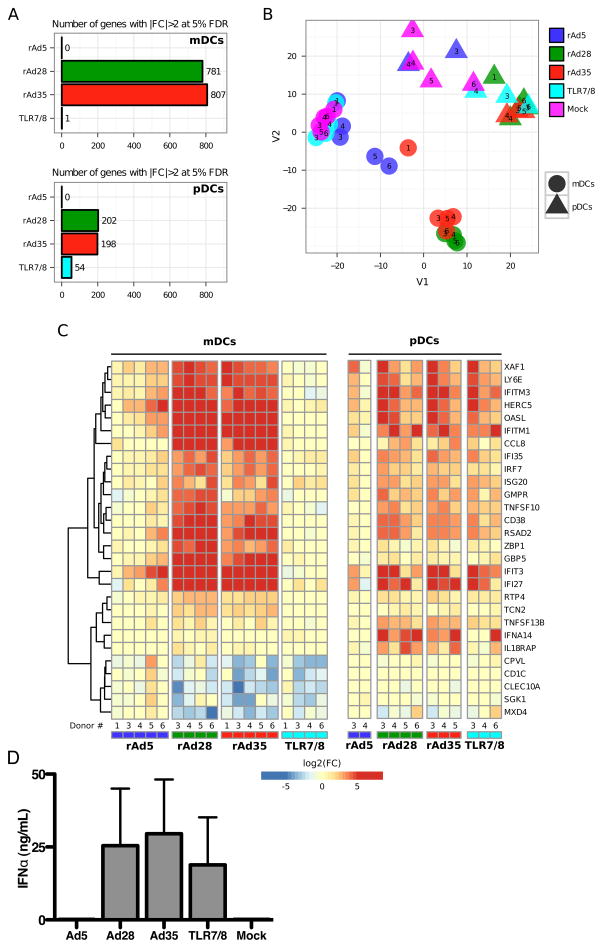

mRNA expression profile

To further characterize the effects of rAd exposure on human DCs, we performed gene array analysis on sorted populations of rAd-infected mDCs and pDCs. Microarrays of mDCs infected with rAd28 and rAd35 showed that the expression levels of 781 and 807 genes were either upregulated or downregulated as compared to donor-matched mock-infected controls, respectively (|FC|>2 at 5% FDR) (Figure 3A). Conversely, no genes were differentially expressed upon infection with rAd5. This difference in impact was also observed with pDCs, where expression levels of 202 and 198 genes were significantly altered upon infection with rAd28 and rAd35, respectively, compared with no changes after infection with rAd5. Many of the genes altered upon infection with rAd28 and rAd35 related directly to type I interferon and type I interferon signaling (Supplementary Figure S1). Pathway analysis with IPA software confirmed that activation of type I interferon was a major effect of infection with rAd28 and rAd35 in both mDCs and pDCs (Supplementary Figure S2). Additionally, 2D multidimensional scaling focusing on interferon related genes (IRGs) revealed that samples infected with rAd28 and rAd35 generally clustered together in mDC and pDC samples, away from the clusters formed by samples infected with rAd5 and mock-infected controls (Figure 3B).

(A) Number of genes differentially expressed relative to the uninfected control (|FC|>2 at 5% FDR). (B) 2D multidimensional scaling. Genes were filtered for IRGs prior to applying the algorithm. (C) Heatmap representation of (log2) fold-changes top most significant IRGs relative to the uninfected control from the same individual. Specifically, genes were selected as the top 10 upregulated and top 10 downregulated IRGs for each incubation separately, subsequently applying a cutoff for statistical significance at |FC|>5 at 5% FDR to limit the number of genes shown. (D) The level of IFNα, measured by ELISA, in the supernatant of pDCs treated with rAd5 vector (MOI1000), rAd28 vector (MOI100), rAd35 vector (MOI100), or TLR7/8-ligand, together with uninfected controls (n= 5).

Many of the genes upregulated by infection with rAd28 and rAd35, but not by rAd5, are directly involved in the type I interferon response in both mDCs and pDCs (Figure 3C). We therefore compared IFNα production induced by these vectors. pDCs infected with rAd28 and rAd35 produced large amounts of IFNα (25 ng/mL±19 and 29 ng/mL±19, respectively), while pDCs infected with rAd5 and uninfected controls did not produce IFNα (Figure 3D). Notably, rAd28 and rAd35 infection led to levels of IFNα production that were similar or higher than those induced by TLR7/8 ligation (19 ng/mL±16).

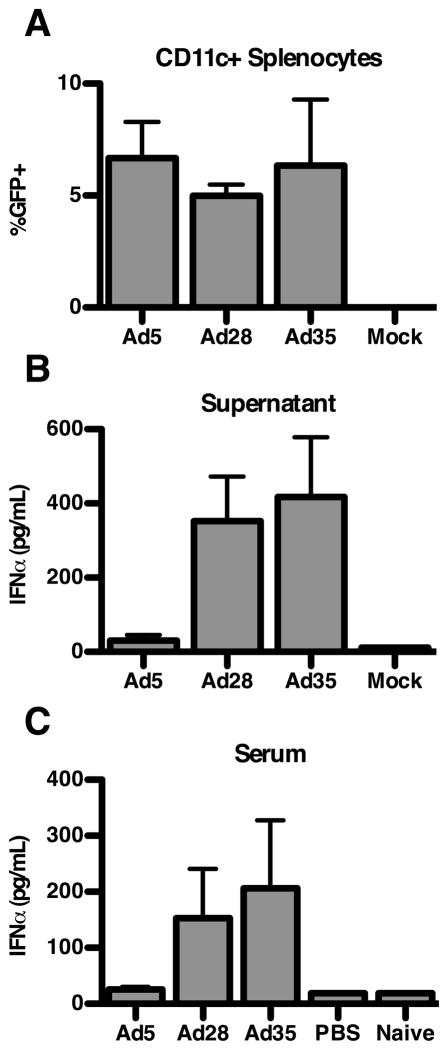

Effects of rAd vectors on IFNα induction in mice

The expression of the receptors for Ad5 (CAR) and Ad35 (CD46) differs between humans and mice (1, 49, 51, 52). We therefore evaluated the ability of rAd5, rAd28, and rAd35 to infect and induce IFNα by isolated mouse DCs. While higher inocula of rAd28 and rAd35 were required to achieve infection, all three vectors were able to infect murine DCs (Figure 4A). Importantly, the pattern of IFNα induction by these vectors held in mouse DCs. As observed in human DCs, only rAd28 (352 pg/ml±121) and rAd35 (417 pg/ml±161) were able to induce IFNα production in mouse DCs, while neither rAd5 nor the uninfected control produced detectable IFNα (Figure 4B). Even when the same inocula of all three vectors were used, rAd28 and rAd35, but not rAd5, induced IFNα production (data not shown). To confirm the differential induction of IFNα production in vivo, we injected mice subcutaneously with the rAd vectors (1×109 VP/mouse). Mice injected with rAd28 and rAd35 vectors had serum IFNα levels of 153 pg/ml±88 and 206 pg/ml±121, respectively, 6 hours post-injection (Figure 4C). Serum IFNα levels in the rAd5-treated, PBS-treated, and naïve mice were all below the detection limit of the kit.

(A) Infection frequencies of sorted murine CD11c+ splenocytes treated with rAd5 vector (MOI1000), rAd28 vector (MOI10,000), or rAd35 vector (MOI10,000), together with uninfected controls (n=5). (B) Levels of IFNα, measured by ELISA, in the supernatant of sorted murine CD11c+ splenocytes treated with rAd5 vector (MOI10,000), rAd28 vector (MOI10,000), or rAd35 vector (MOI10,000), together with uninfected controls (n=5). (C) Serum levels of IFNα, measured by ELISA, in mice immunized with rAd5 vector (1×109 VP/mouse), rAd28 vector (1×109 VP/mouse), or rAd35 vector (1×109 VP/mouse), together with PBS-injected and naïive controls, at 6 hours post-vaccination. (n=5)

Role of IFNα in the immunogenicity of rAd vectors in mice

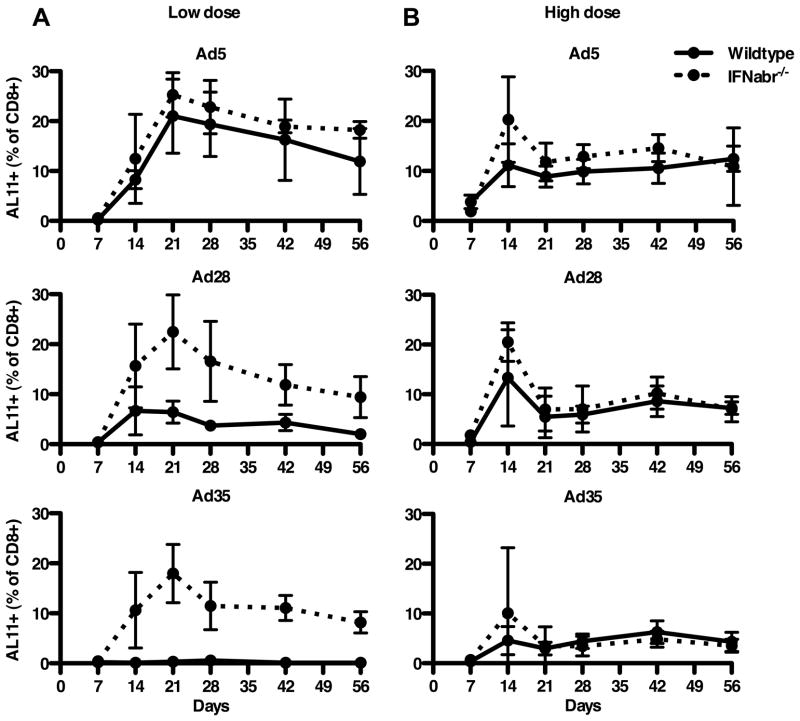

Since the data generated both with human and murine cells showed that high levels of IFNα were induced by rAd28 and rAd35, but not by rAd5, we investigated the impact of this differential IFNα induction on vector immunogenicity. Previous studies have shown that rAd5 is significantly more immunogenic at lower doses than either rAd28 or rAd35 (13). We therefore immunized both wildtype and IFNabr−/− mice with a low dose (5×107 VP/mouse) of each rAd vector encoding a SIV Gag insert and compared the magnitude of the induced T cell response by quantifying the number of tetramer+ CD8 T cells specific for a dominant epitope derived from SIV Gag (AL11) (53). Only rAd5 immunization was able to induce a large AL11-specific T cell response in both wildtype (peak 21.0%±7.4) mice and IFNabr−/− (peak 25.3%±4.5) mice (Figure 5A, top panel). Both rAd28 (peak 22.5%±7.4) and rAd35 (peak 18.0%±5.8) immunization induced a frequency of AL11-specific T cells similar to that induced by rAd5 in the IFNabr−/−mice, but not in the wildtype mice (Figure 5A, middle and bottom panels). Wildtype mice developed a small AL11-specific CD8 T cell response after immunization with rAd28 (peak 6.4%±2.2), and no measurable response was generated by rAd35 immunization. This difference in immunogenicity between wildtype and IFNabr−/− mice immunized with rAd28 and rAd35 could be overcome by increasing the immunization dose. At a 20-fold higher inoculation (1×109 VP/mouse), all three vectors showed similar immunogenicity in wildtype and IFNabr−/− mice (Figure 5B).

Frequencies of AL11-specific CD8 T cells, quantified by tetramer staining, after low dose (5×107 VP/mouse) (A) (n=5) and high dose (1×109 VP/mouse) (B) (n=4) vaccination of wildtype and IFNabr−/− mice with rAd5 vector, rAd28 vector, or rAd35 vector, all encoding SIV Gag.

rAd vector-induced IFNα signaling and CD8 T cell memory phenotype and function

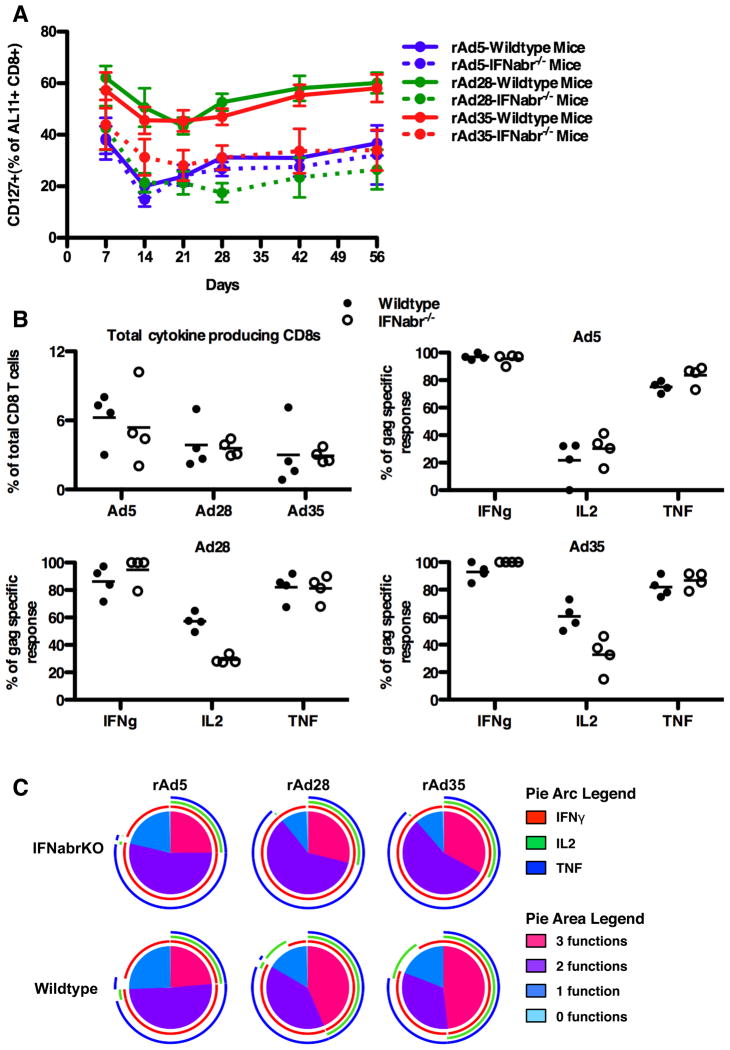

Next, we determined the impact of excess IFNα production on long-term memory differentiation as defined by CD127 (IL-7 receptor) expression (54) in the high-dose immunized mice. Groups with either no induction of IFNα (rAd5-wildtype, rAd5-IFNabr−/−) or groups with interrupted IFNα signaling (rAd28-IFNabr−/−, rAd35-IFNabr−/−) failed to establish high percentages of AL11+ CD8 T cells that expressed CD127 (32.4%±15.4). In contrast, groups with intact IFNα induction and signaling (rAd28-wildtype, rAd35-wildtype) maintained a much higher percentage of AL11+ CD8 T cells that expressed CD127 (59.1%±8.8) (Figure 6A).

(A) Frequencies of CD127+ AL11-specific CD8 T cells from mice vaccinated with a high dose of rAd5 vector, rAd28 vector, or rAd35 vector (n=4). (B) Top left panel: frequencies of AL11 peptide-stimluated CD8 T cells producing IFNγ, IL2, or TNF after vaccination of wildtype or IFNabr−/− mice with rAd5 vector, rAd28 vector, or rAd35 vector (n=4). Top right and lower panels: frequencies of IFNγ+, IL2+, or TNF+ cells as a percentage of the total AL11-specific response for each vector (n=4). (C) SPICE plots illustrating the functionality of AL11-specific CD8 T cells from wildtype and IFNabr−/− mice vaccinated with rAd5 vector, rAd28 vector, or rAd35 vector (n=4).

To determine cytokine production profiles in SIV Gag-specific CD8 T cells from high-dose immunized mice, we measured the frequency of IFNγ, IL2, and TNF producing CD8 T cells by flow cytometry after stimulation with the AL11 peptide. Overall, mice vaccinated with the rAd5 vector had slightly greater numbers of cytokine-producing cells than mice vaccinated with the rAd28 or rAd35 vectors (Figure 6B, top left panel). This observation, although not statistically significant, is consistent with the larger AL11-specific CD8 T cell populations detected after high-dose vaccination. No significant differences in the frequency of cytokine-producing CD8 T cells between wildtype and IFNabr−/− mice were observed in any of the groups (Figure 6B).

When measured as a fraction of the total AL11-specific CD8 T cell response, wildtype mice vaccinated with rAd28 or rAd35 exhibited higher proportions of IL2-producing cells (57.2%±6.3 and 60.6%±10.0, respectively) compared to their IFNabr−/− counterparts (29.22%±2.9 and 32.7%±13.2, respectively) (Figure 6B, lower panels). Both wildtype and IFNabr−/− mice vaccinated with rAd5 had low percentages of IL2 producing cells (21.7%±15.2 and 30.3%±10.7, respectively) (Figure 6B, upper right panel). Wildtype mice vaccinated with rAd28 and rAd35 had a higher proportion of their response dedicated to the co-expression of three cytokines (IFNγ+ TNF+ IL2+) than IFNabr−/− mice (Figure 6C). This difference was mostly due to the higher proportion of IL2-producing cells in the wildtype mice vaccinated with rAd28 and rAd35. Both wildtype and IFNabr−/− mice vaccinated with rAd5 displayed a relatively lower proportion of triple cytokine positive AL11-specific CD8 T cells.

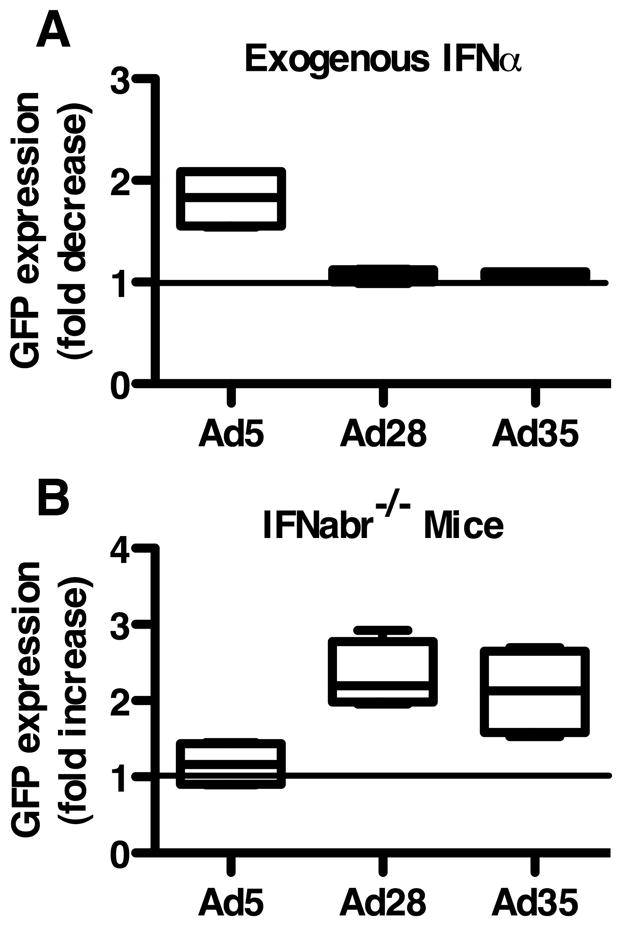

Impact of IFNα on insert expression

We next examined the role of IFNα production on insert expression by the rAd vectors in order to determine a possible mechanism for the differing immunogenicity. To determine this we first compared the infectivity of each vector in wildtype mouse DCs exposed or not exposed to exogenous IFNα. rAd5-infected DCs treated with IFNα were found to have a 1.8-fold decrease in GFP expression compared with untreated rAd5-infected DCs (Figure 7A). No difference in GFP expression was detected between IFNα treated or untreated DCs infected with rAd28 or rAd35.

(A) Fold decrease in GFP expression in rAd-infected, IFNα-treated DCs from wildtype mice compared with rAd-infected, IFNα untreated DCs. (B) Fold increase in GFP expression in rAd-infected DCs from IFNabr−/− mice compared to rAd-infected DCs from wildtype mice.

We also compared the infectivity of the rAd vectors in DCs isolated from IFNabr−/− mice to DCs from wildtype mice. In rAd5-infected samples we found no difference in GFP expression between wildtype and IFNabr−/− DCs (Figure 7B). In rAd28 and rAd35-infected samples DCs from IFNabr−/− mice expressed GFP at over twice the rate of wildtype DCs.

Discussion

rAd vectors have been studied for potential use in vaccination strategies because of their ease of construction and ability to infect a large number of cells. Vectors constructed from Ad5 are efficient at eliciting large T cell responses, but are limited clinically by extensive preexisting immunity in the general population. Rare serotype adenoviral vectors, such as rAd28 and rAd35, circumvent issues related to preexisting immunity, but are less immunogenic than rAd5. The goal of this study was to determine what accounts for some of the differences in the immunogenicity of rare serotype rAd vectors.

DCs play an important role in both the initiation of innate immunity and the development of adaptive immunity (55). This dual function, combined with the important role that DCs play in anti-viral immunity, led us to investigate the impact of rAd exposure on two blood DC subsets, mDCs and pDCs (56). Notably, both rAd28 and rAd35 exerted substantial effect on both mDCs and pDCs, particularly with respect to IFNα production and maturation. In striking contrast, rAd5 did not infect pDCs and had almost no detectable impact on either DC population, including any effects on IFN-related pathways. It has been proposed that vectors that induce innate immunity might perform better as vaccines due to potential adjuvant effects (1). Alternatively, vectors that do not alter the host cell or activate innate immunity are considered ideal for gene therapy, where immunity can prove detrimental (57, 58).

Here we show that increased innate immune activation, notably IFNα signaling, by rAd vectors can have detrimental effects on the immunogenicity of the insert, reducing the magnitude of the resulting CD8 T cell response. IFNabr−/− mice, when vaccinated with rAd28 and rAd35, could not respond to the IFN, and developed more robust CD8 T cell responses compared to wildtype mice, and similar to those observed after rAd5 vaccination.

The mechanisms responsible for reduced immunogenicity in the presence of IFNα are not well understood. IFNα can act in an autocrine manner, upregulating and activating RNase L and PKR, two potent host antiviral proteins (59). RNase L and PKR shut down host transcription and translation respectively and could potentially reduce insert expression or increase apoptosis in infected APCs, thereby reducing vector immunogenicity. Notably, our observations that IFNα reduces the number of insert positive cells after rAd exposure strongly support this possible mechanism. Additionally, the fact that the addition of exogenous IFNα to rAd28 and rAd35 exposed DCs does not further decrease the fraction of insert positive cells suggests that the amount of vector-induced IFNα produced is already a maximally suppressive dose and that this suppression is limited to a twofold reduction of insert expression in vitro. This incomplete reduction in vector expression by IFNα signaling may explain why immunogenicity can be restored by increasing the vaccine dose. Despite the partial suppression of insert expression by IFNα, the magnitude of insert positive cells can still attain a necessary immunogenicity threshold.

Additionally, IFNα has been shown to have multiple paracrine activities. At a high inoculum of rAd28 and rAd35, we observed that vaccine-elicited CD8 T cells from wildtype mice were more polyfunctional and had a more pronounced long-term memory phenotype than the vaccine-elicited CD8 T cells from IFNabr−/− mice or mice vaccinated with rAd5. These findings are consistent with prior observations showing an increased long-term memory phenotype in CD8 T cells stimulated with IFNα (31). It is also feasible that CD8 T cell expansion in the presence of IFNα leads to a predominantly central memory-like phenotype, which has previously been associated with enhanced polyfunctionality due to the retention of IL2 production (60). Alternatively, separate mechanisms may be operating to mediate these distinct effects. IFNα has also been shown to either promote or suppress T cell proliferation and survival depending on the timing, level, and duration of exposure. The effects of IFNα signaling on CD8 T cell proliferation and survival after vaccination with rAd vectors are not fully understood. However, the inherent paradox of our results is that vector-induced IFNα production can lead to a reduction in the magnitude of the CD8 T cell population while simultaneously increasing the quality and longevity of the response.

The mechanism(s) underlying the differential induction of IFNα by rAd5 and the lower seroprevalence vectors, rAd28 and rAd35, is currently unknown. All three vectors used in our study are E1-deleted, rendering them replication-deficient and greatly reducing the transcription of the viral genome. Importantly, expression of two non-translated viral RNA sequences, Viral Associated-RNA (VA-RNA) I and VA-RNA II, transcribed by host RNA polymerase III, are only partially downregulated (61, 62). These sequences are likely transcribed in infected host cells. All Ad serotypes contain a VA-RNA I sequence, and most encode a VA-RNA II (63). rAd5 VA-RNA I has been shown to inhibit RNase L and PKR function, as well as alter gene expression by functioning as miRNAs (64, 65). The function of Ad5 VA-RNA II is not well understood but it may play a compensatory role in VA-RNA I-deleted vectors (66). The sequences of VA-RNAs vary greatly between rAd5, rAd28, and rAd35, and it is unknown if VA-RNAs from rAd28 or rAd35 function in a similar manner (63). It is known, however, that rAd5 VA-RNAs induce moderate IFNα production at high doses (MOI 10,000) by stimulating host PPRs (62). It is possible that rAd28 and rAd35 stimulate IFNα production through a similar mechanism at lower MOI due to differences in VA-RNA sequence or expression levels, rendering them more efficient vectors for inducing IFNα. Alternatively, different factors, such as surface receptor engagement, route of entry, intracellular trafficking patterns, and CpG content of the genome may also be involved in the induction of IFNα (67, 68). Further research is required to determine which of these factors are responsible for the differential induction of IFNα by various rAd vectors.

In conclusion, our results show that, in stark contrast to rAd28 and rAd35, rAd5 fails to induce significant changes in DC mRNA expression or maturation. IFNα production and induction of IFN-related pathways is characteristic of rAd28 and rAd35 infection of DCs, and this leads to a decrease in the magnitude, but an improvement in the long-term memory potential (CD127 expression) and cytokine polyfunctionality of the insert-specific CD8 T cell response. The presence and impact of IFNα production and signaling should therefore be taken into account when designing future rAd vectors.

Supplementary Material

1

2

3

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1103717

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.jimmunol.org/content/jimmunol/188/12/6109.full.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Article citations

An Oil-Based Adjuvant Improves Immune Responses Induced by Canine Adenovirus-Vectored Vaccine in Mice.

Viruses, 15(8):1664, 30 Jul 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37632007 | PMCID: PMC10458467

Comparative analysis of the impact of 40 adenovirus types on dendritic cell activation and CD8+ T cell proliferation capacity for the identification of favorable immunization vector candidates.

Front Immunol, 14:1286622, 17 Oct 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37915567 | PMCID: PMC10616870

Two Novel Adenovirus Vectors Mediated Differential Antibody Responses via Interferon-α and Natural Killer Cells.

Microbiol Spectr, 11(4):e0088023, 22 Jun 2023

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 37347197 | PMCID: PMC10434031

Adenovirus vector and mRNA vaccines: Mechanisms regulating their immunogenicity.

Eur J Immunol, 53(6):e2250022, 20 Nov 2022

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 36330560 | PMCID: PMC9877955

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The use of adenoviral vectors in gene therapy and vaccine approaches.

Genet Mol Biol, 45(3 suppl 1):e20220079, 07 Oct 2022

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 36206378 | PMCID: PMC9543183

Go to all (37) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

GEO - Gene Expression Omnibus

- (1 citation) GEO - GSE37128

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Type I interferon-dependent activation of NK cells by rAd28 or rAd35, but not rAd5, leads to loss of vector-insert expression.

Vaccine, 32(6):717-724, 08 Dec 2013

Cited by: 15 articles | PMID: 24325826 | PMCID: PMC3946768

Myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells are susceptible to recombinant adenovirus vectors and stimulate polyfunctional memory T cell responses.

J Immunol, 179(3):1721-1729, 01 Aug 2007

Cited by: 63 articles | PMID: 17641038 | PMCID: PMC2365753

Comparative analysis of the magnitude, quality, phenotype, and protective capacity of simian immunodeficiency virus gag-specific CD8+ T cells following human-, simian-, and chimpanzee-derived recombinant adenoviral vector immunization.

J Immunol, 190(6):2720-2735, 06 Feb 2013

Cited by: 80 articles | PMID: 23390298 | PMCID: PMC3594325

Use of adenovirus in vaccines for HIV.

Handb Exp Pharmacol, (188):275-293, 01 Jan 2009

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 19031031

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Intramural NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: Z99 AI999999

NIAID NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: Y99 AI999999