Abstract

Free full text

Persistent inflammation and immunosuppression: A common syndrome and new horizon for surgical intensive care

Abstract

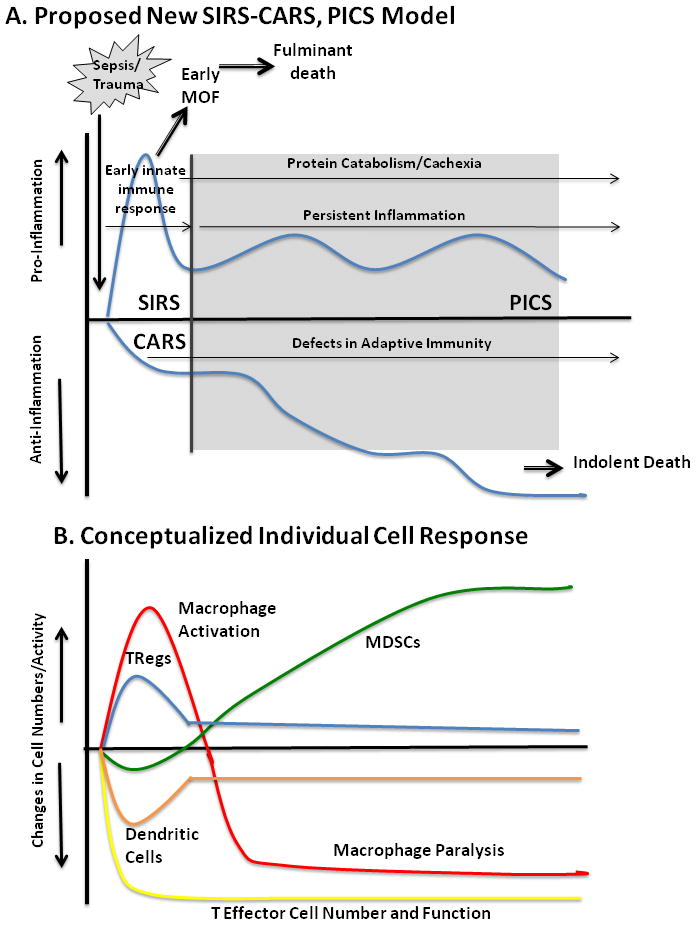

Surgical intensive care unit (ICU) stay of greater than ten days is often described by the experienced intensivist as a ‘complicated clinical course’, and is frequently attributed to persistent immune dysfunction. ‘Systemic inflammatory response syndrome’ (SIRS) followed by ‘compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome’ (CARS) is a conceptual framework to explain the immunological trajectory that ICU patients with severe sepsis, trauma or emergency surgery for abdominal infection often traverse, but the causes, mechanisms and reasons for persistent immune dysfunction remain unexplained. Often involving multiple organ failure (MOF) and death, improvements in surgical intensive care have altered its incidence, phenotype and frequency, and have increased the number of patients who survive initial sepsis or surgical events and progress to a persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PICS). Often observed, but rarely reversible, these patients may survive to transfer to a long-term care facility only to return to the ICU, but rarely to self sufficiency. We propose that PICS is the dominant pathophysiology and phenotype that has replaced late MOF, and prolongs surgical ICU stay, usually with poor outcome. This review details the evolving epidemiology of MOF, the clinical presentation of PICS, and our understanding of how persistent inflammation and immunosuppression defines the pathobiology of prolonged intensive care. Therapy for PICS will require efficacy for multiple immune system defects and protein catabolism, and will involve innovative interventions for immune system rebalance and nutritional support to regain physical function and well being.

Evolving epidemiology of multiple organ failure (MOF)

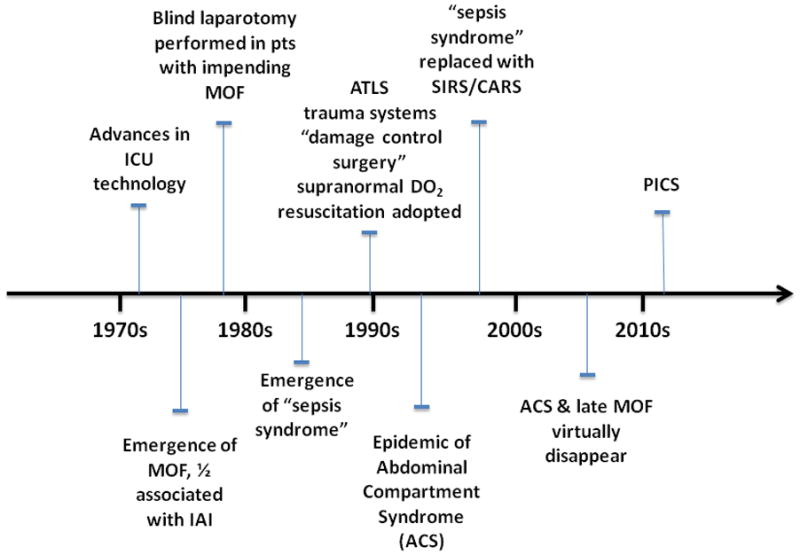

MOF emerged in the early 1970s as a result of advances in ICU technology that enabled patients to survive single organ failure1. Its epidemiology continues to change as our management strategies evolve from ongoing research (Figure 1). In the late 1970s, reports by Polk, Eiseman, and Fry promoted the belief that MOF was the ’fatal expression of uncontrolled infection‘, and focused research on infection-driven MOF1. Over half of MOF cases were associated with intra abdominal infection (IAI). Throughout the 1980s, IAI became less problematic due to advances in surgery and intensive care including: a) better initial management of abdominal trauma and IAI, b) more potent and appropriately dosed perioperative antibiotics, c) earlier diagnosis of postoperative IAI with advanced computerized axial tomography, and d) effective percutaneous abscess drainage using interventional radiology.

Summary of the evolution of clinical management of MOF and shock secondary to trauma and sepsis beginning with the emergence of MOF in the 1970s, through today’s currently proposed phenotype PICS.

A series of reports from Europe by Faist, Goris, and Waydhas convincingly demonstrated that MOF was a frequent occurrence in blunt trauma patients without infection2–4. The term ’sepsis syndrome‘ became the vernacular to describe patients who appeared to be septic but had no obvious source of infection. The central question became: ’What is the driving mechanism of this deleterious inflammation?’ Given that shock was a consistent early event, whole body ischemia-reperfusion was an attractive explanation. Alternatively, epidemiologic studies by Border and others strongly implicated the gut as the occult source of bacteria that drove the sepsis syndrome5. Indeed, prospective randomized controlled trials (PRCTs) testing selective gut decontamination and early enteral nutrition found decreased rates of nosocomial infection (principally pneumonia) with these gut-directed therapies6. These clinical observations were supported by the experimental work of Alexander and others that persuasively focused attention on bacterial translocation as a unifying mechanism that characterized non infectious induced MOF7.

In the late 1980s, Shoemaker popularized an alternative hypothesis that ’early unrecognized flow dependent oxygen consumption‘ was a prime cause of non infectious MOF8. Pushing oxygen delivery (DO2) to ‘supranormal’ levels during initial resuscitation became standard of care. Simultaneously, trauma system triage, Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and ’damage control‘ surgery were universally adopted. As a result, severely injured patients were triaged to designated trauma centers, underwent damage control surgery and in the ICU, received supranormal DO2 resuscitation. Fewer patients exsanguinated and more survived to ICU admission. Many developed abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS), which emerged as an epidemic in the mid 1990s and was subsequently shown to be another deadly MOF phenotype9.

By the mid 1990s, ‘Sepsis syndrome’ had evolved into the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). SIRS was presumed to be inherently beneficial; however, if exaggerated or perpetuated, SIRS could precipitate early MOF, independent of infection. It was not until the first decade of the new millennium that Polly Matzinger provided an explanation for SIRS in absence of obvious microbial infection: the host responds to noninfectious insults and tissue injury by releasing endogenous mediators that are ‘danger signals’10. Tissue damage, per se, releases ‘alarmins’ and ‘damage-associated molecular pattern’ (DAMP) molecules that can stimulate innate immunity through TLR receptors or other sensing systems11, 12. Thus, noninfectious insults can elicit exaggerated inflammation through the same pathway(s) as microbial pathogens and produce similar SIRS.

Also in the mid 1990s, analysis of the Denver MOF database revealed that MOF occurred ‘early’ or ‘late’ in the surgical ICU course13. Two different patterns of SIRS induced early MOF. The ‘one hit’ model, i.e. a massive initial insult culminating in early fulminant SIRS and MOF, or the ‘two hit’ model, i.e. resuscitating severely injured patients with SIRS, followed by an early second inflammatory insult (e.g. pulmonary aspiration, blood transfusion, or early orthopedic intervention) amplifying SIRS to induce early MOF1. This was believed due to priming and activation of innate immune response (principally PMN mediated). SIRS was followed by delayed immunosuppression, often leading to late infection, which, in turn, appeared to precipitate late MOF after 7 to 10 days.

By the early 2000s, ongoing research revealed that many time honored ICU interventions (e.g. high tidal volume mechanical ventilation, high volume crystalloid resuscitation, liberal blood transfusions, early TPN, intermittent hemodialysis) were actually promoting nosocomial infection and late MOF. Over the last decade, with more consistent delivery of evidence-based care to minimize these practices, ACS has become rare, mortality from traumatic shock-induced MOF has decreased substantially, and late MOF has disappeared14–16.

However, this decrease in MOF incidence has not been observed with sepsis. Despite tremendous research efforts, sepsis remains a leading cause of MOF and prolonged ICU stay 17. With the advancing age of our population, the incidence of sepsis is increasing, and mortality remains prohibitively high (>40%) for patients who are allowed to progress into septic shock18.

Early sepsis is often difficult to recognize, and for most patients presenting early sepsis, the initial diagnosis is delayed or missed. Many interventions are known to have an impact on outcome, but are often administered in haphazard fashion. Optimal management strategies require assessment and implementation of current evidence-based standard operating procedures (SOPs). Such approaches have been successfully demonstrated by the recent ’Glue Grant‘ experience19, the ‘Surviving Sepsis Campaign,’20 ARDSNET, and other evidence-based guidelines (EBGs). A widely recognized challenge is bedside implementation of EBGs in daily intensive care of the individual patient. Recent audits have shown surprisingly low compliance with widely accepted EBGs and substantial improvement in outcomes by strategies that only modestly improve compliance16, 21.

One approach that has consistently demonstrated improved implementation of evidence-based care and patient outcome is computerized clinical decision support (CCDS). With rule sets devised by the ICU clinician team, computerized protocol systems standardize clinical decision making, ensure high compliance, and consistently out-perform expert ICU clinicians22. EBG implementation not only improves outcome, but also provides a more stable platform for multicenter prospective randomized clinical studies, because confounding effects of variable care are controlled and ongoing process improvement is stimulated.

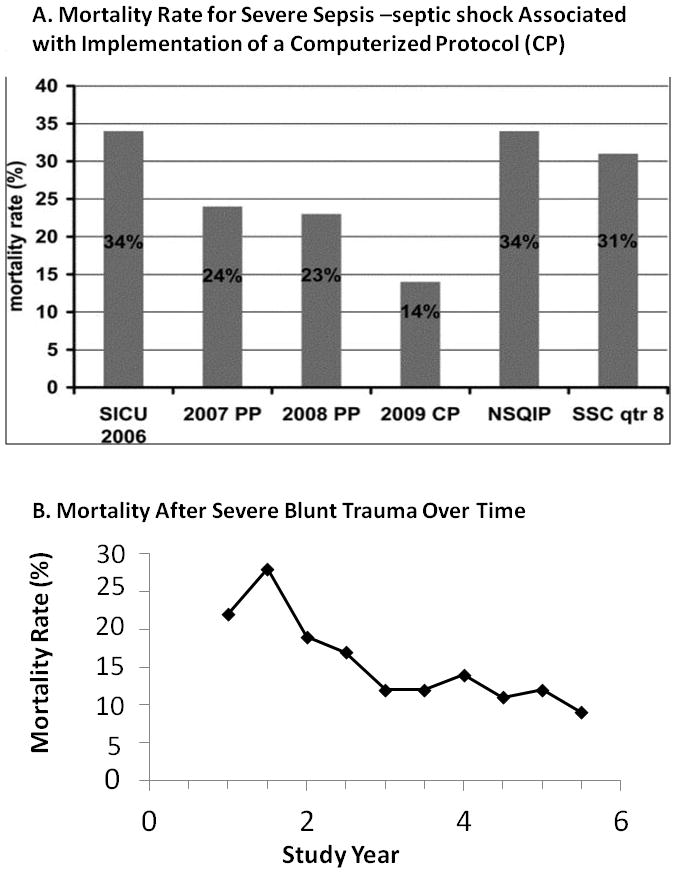

Implementation of CCDS has resulted in a surprisingly large decrease in mortality rate from severe sepsis (Figure 2A). Mortality rate from early fulminant SIRS has decreased significantly because intervention occurs prior to development of septic shock. Similar results were found with the Glue Grant experience in patients with severe blunt trauma using multi-site, consensus derived, evidence based standardized SOPs (Figure 2B)19. Glue Grant participants found modest compliance with agreed evidence-based SOPs to be associated with dramatic reduction of overall mortality rate from approximately 22% pre SOP to 11% after SOP implemenation.

A. Yearly mortality rate (2006–2009) for patients treated for severe sepsis-septic shock in The Methodist Hospital SICU compared with Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) guideline-based performance improvement initiative and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) data. In 2006 (before initiation of sepsis protocols), mortality rate in TMH SICU was 34%. In 2007 (as sepsis screening and our sepsis protocol were implemented using a paper protocol (PP)), mortality rate decreased to 24%. In 2008 (using the PP), mortality rate was 23%. In 2009 (with implementation of computerized sepsis protocol (CP)), mortality rate decreased to 14%. For comparison, 31% mortality rate was reported in the eighth quarter of the SSC PI initiative and 34% as reported in a recent NSQIP analysis. Reprinted with permission from Journal of Trauma98.

B. The overall mortality rate for blunt trauma from the Glue Grant study cohort decreased during the study period from 22% in the first two years to 11% in the last two years (p<0.01), as guidelines were implemented and compliance increased. Reprinted with permission from Annals of Surgery19.

However, there remain a large number of patients who linger in the ICU with manageable organ dysfunctions, but who usually do not meet established criteria for late MOF. Their clinical course is characterized by ongoing protein catabolism with poor nutritional status, poor wound healing, immunosuppression and recurrent infections. These patients are commonly discharged to long term acute care (LTAC) facilities, but due to excessive loss of lean body mass and prolonged immunosuppression, often develop secondary nosocomial infections and rarely rehabilitate or return to functional life.

We propose that this ‘persistent inflammation - immunosuppression catabolism syndrome (PICS)’ is the predominant phenotype that has replaced late occurring MOF in surgical ICU patients who fail to recover. Clinical management of these patients as they progress irreversibly toward indolent death is perhaps the most challenging problem currently confronting surgical intensive care.

SIRS, CARS and their current relevance to PICS

Since the first identification of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1 and TNFα) in the 1980s23, 24, death from sepsis was presumed to be due to an early overabundant innate immune response. Over production of multiple pro-inflammatory mediators, PMN activation, endothelial injury, and inadequate perfusion and tissue damage caused early MOF, and lead to death25–27. This process was driven by exposure to infectious products, such as PAMPs (pathogen-associated molecular patterns)28 or by endogenous danger signals (DAMPs and alarmins)11, 12 acting through TLR or NOD signaling pathways29. The end results were similar: activation and over expression of early response genes, driven in large part through NF-kB activation30. There have been nearly 150 clinical trials of biological response modifiers, most testing agents that attempt to block this early proinflammatory response17, 31. All but one of these studies failed to demonstrate efficacy32. The only FDA drug approved for severe sepsis / septic shock (Xigris™, activated protein C) was voluntarily withdrawn from the market in late 2011 due to failure of post-marketing clinical trials to confirm earlier outcome benefit 33.

Anti-inflammatory approaches to sepsis have failed because of conceptual and technical difficulties. Because of the rapid onset of the innate immune response, treatments initiated hours after the onset of symptoms have inevitably missed the early inflammatory mediator release and initiation of inflammatory cascades34. In addition, redundancy of the early inflammatory mediator cascades has made success of monotherapies unlikely34. Preclinical studies to investigate the efficacy of these drugs had a uniformly lethal effect in rodent and primate models. Eichacker performed an enlightening meta-analysis showing that the efficacy of anti-TNFα in severe sepsis positively correlated with the mortality rate of the control group35. Anti TNF-α therapies were beneficial in the most seriously ill, but actually harmful in less ill patients36.

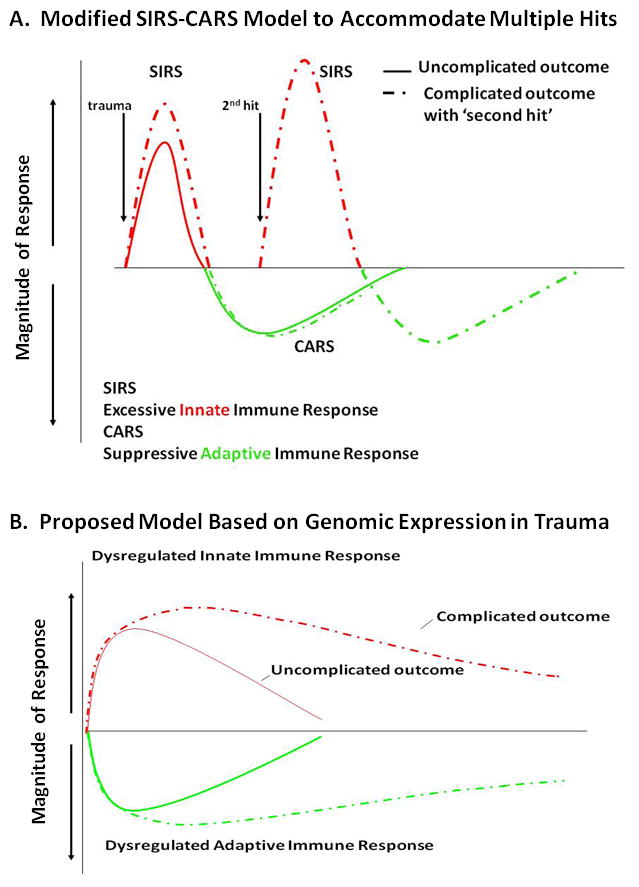

Concordantly, it was well known as early as the 1970s that severe trauma and sepsis were associated not only with exaggerated inflammation, but also with an immune compromised state37. With the definition of SIRS, Roger Bone described the post inflammatory immune suppression and coined the term ‘compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome’ (CARS ) (Figure 3A)38. CARS was first described as an ‘anti-inflammatory response’ characterized by increased appearance in the circulation of anti inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-10 and IL-6) and cytokine antagonists (e.g. IL-1ra and sTNFRI) 38. In animal models, the appearance of these cytokines was delayed when compared to early inflammatory mediators (i.e. TNF-α following endotoxemia or Gram negative bacteremia39, 40. In critically ill patients, concentrations of these anti-inflammatory mediators were found to be increased for days and weeks, while proinflammatory cytokines ‘disappeared’41, 42. The ‘compensatory’ nature of this response was demonstrated in baboons and chimpanzees, and then in humans, by van der Poll, Lowry and Fong, who reported that blockade of the early inflammatory response with TNF-α inhibitors prevented appearance or release of anti inflammatory cytokines and cytokine antagonists43–45.

A. The traditionally accepted SIRS-CARS phenomenon holds that mortality from severe sepsis and injury is a consequence of an overabundant and dysregulated early innate immune response from the over production of proinflammatory mediators and cytokines, leading to endothelial injury, tissue damage, inadequate perfusion and MOF, ultimately leading to death. In patients who survive this early SIRS event, a compensatory anti-inflammatory responses (CARS) including suppression of adaptive immunity results. Additional insults such as nosocomial infection can cause a late “second-hit” that may lead to recurrent SIRS. B. Recently, the Glue Grant showed that based on leukocyte genomic expression patterns, there is a simultaneous induction of innate (both pro- and anti-inflammatory genes) and suppression of adaptive immunity genes, and that there is minimal genomic or clinical evidence for a “second-hit” phenomenon. Reprinted with permission from Journal of Experimental Medicine19.

By the 1990s, it was well recognized that patients with severe sepsis not only exhibited an ongoing inflammatory response, but also exhibited multiple defects in adaptive immunity. The early findings of Meakins and others from the 1970’s showed that critically ill patients could not mount a delayed type hypersensitivity response to common antigens46 and that T cell proliferation was markedly suppressed47. CARS had become the moniker for all the shared defects in adaptive immunity that accompany severe trauma and sepsis, including decreased antigen presentation, macrophage paralysis, depressed T-cell proliferative responses, increased lymphocyte and dendritic cell apoptosis, and shift from TH1 to TH2 lymphocyte phenotype (Table 1).

Table 1

Adaptive Immunity Changes in Severe Sepsis and Trauma

| Adaptive Immune Changes | Reference(s) |

|---|---|

| Increased Tregs | (75) |

| T cell anergy | (27,38) |

| T cell polarization-shift from TH1 to TH2 phenotype | (51) |

Macrophage Paralysis

| (53,54) |

| Apoptosis induced lymphocyte depletion | (59) |

| Suppressed T cell proliferation | (73) |

| Up-regulation of PDL-1, BTLA, CTLA, HVEM | (17, 66, 67, 68) |

The scientific community came to conclude that the sequence of early proinflammation (SIRS) and later anti inflammation (CARS) was responsible for adverse outcomes after severe trauma and sepsis (Figure 3A)27. Just as MOF has evolved, this SIRS - CARS paradigm has been challenged on several fronts. The ‘compensatory’ nature of CARS has been questioned in commonly used models of sepsis, including the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) and colon ascendens stent peritonitis (CASP)48, 49. In these models of polymicrobial or abdominal sepsis, blocking early proinflammatory response had no effect on either anti inflammatory response or suppression of adaptive immunity. Additionally, the concept that CARS is ‘delayed’ relative to SIRS has been criticized and revised. Osuchowsky and Remick were first to report that production of anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory cytokines occurs simultaneously in a poly microbial sepsis model50. More dramatically, Xiao and colleagues provided convincing evidence from genome wide expression analysis of blood leukocytes after severe blunt trauma in humans that down regulation of genes involved in T cell responses, and that antigen presentation and upregulation of anti-inflammatory gene expression, parallels increased expression of proinflammatory genes19. The Glue Grant has proposed a new model to replace the classic model of SIRS - CARS, in which induction of both responses occurs simultaneously (Figure 3B)19.

Another component of the traditional SIRS – CARS paradigm is that proinflammation occurs early and is terminated by development of CARS. This belies experimental data suggesting that in critically ill patients with immunosuppression, inflammation is persistent but attenuated compared to the initial inflammatory event51. This persistent inflammation is characterized by increased concentration of plasma IL-6, a persistent acute phase response, neutrophilia, with increased immature granulocyte count, anemia, lymphopenia, and, often, tachycardia. Although these patients are profoundly immunosuppressed, inflammation is ongoing. Importantly, this deranged inflammation – immunosuppression process is consuming energy derived from adipose and protein catabolism. Despite aggressive nutritional intervention, ongoing catabolism results in substantial loss of lean body mass and proportional decrease in functional status.

Modern ICUs are proficient with early recognition and treatment of SIRS. As a result, many patients survive their initial sepsis or emergency surgical insult only to encounter prolonged, complicated ICU courses52. In leading centers of expertise, emphasis is no longer targeting exaggerated proinflammation, but identifying mechanisms that drive prolonged immunosuppression, and searching for new therapies that prevent it or restore immune function31.

Understanding the Basis for Immunosuppression Associated with Critical Illness

Terminally differentiated macrophages (e.g. Kupffer cells and splenic macrophages), blood monocytes and dendritic cells are key effector cells that remove pathogens and present antigens in innate immunity. Macrophage dysfunction is a significant contributor to both innate and adaptive immune suppression53. As bacterial clearance is decreased54 and capacity to present antigens and release proinflammatory cytokines is also decreased53, the patient enters a state of ’immune paralysis‘, and is vulnerable to secondary infection27. Small studies testing immunostimulatory therapies to reverse monocyte deactivation indicate that these may be successful treatments of sepsis induced immunosuppression55,56. Docke et al tested administration of IFN-α in septic patients and found marked reduction in monocyte HLA-DR expression56. Meisel et al administered GM-CSF to septic patients with immunosuppression identified by decreased monocyte HLA-DR receptor expression57. They showed that GM-CSF was effective in restoring macrophage immunocompetence and was associated with decreased ICU length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation57. These reports indicate that, in refractory sepsis, the immune system is so severely compromised that immunostimulatory therapy does not unbridle the proinflammatory response seen in early sepsis17.

Another facet of sepsis induced immunosuppression involves defective T-cell lymphocytes, including apoptotic depletion58, 59, decreased proliferation60, and Th2 polarization60, 61. Programmed death 1 (PD-1) protein (a negative costimulatory molecule expressed on a number of immune cells) prevents T-cell proliferation, causes T-cells to become nonresponsive, and increases monocyte production of IL-1017, 62. The PD-1 : PDL pathway is thought to be critical in chronic infections such as HIV, but its role in innate and adaptive immunity following sepsis has yet to be elucidated62, 63. Recently, Huang et al showed that absence of PD-1 increases survival rate after polymicrobial sepsis in PD-1 knockout mice62. In addition to effects on T cell effector function, increased expression of PD-1 on macrophages and monocytes during sepsis is associated with their functional decline, indicating that this survival advantage may be secondary to a macrophage effect 62. Similarly, Hotchkiss et al showed that, when using a PD-1 receptor antibody initiated 24 hours after the onset of polymicrobial sepsis in mice, survival rate increased64. When examining septic patients, these investigators found that T lymphocytes in the spleen and lung had increased expression of PD-1 and splenic capillary endothelial cells had increased expression of PD-L165. Recently, Said et al showed that PD-1 impairs immunity via increased production of IL-1063. They found that, in HIV patients, PD-1 activation results in increased IL-10 secretion from monocytes, and that, when the PD-1 : PD-1 receptor interaction is blocked, PD-1 induced inhibition of CD4 T cells was reversed17, 63. Other inhibitory peptides that may be involved in adaptive immune suppression during sepsis and trauma include CTLA4, BTLA and HVEM66–68.

The antiapoptotic cytokine IL-15 may be another novel therapeutic agent to target both innate and adaptive immunity. IL-15 has a broad range of function. It acts as an anti apoptotic cytokine, and augments IFN-α expression, which may help reverse monocyte dysfunction in sepsis, and, therefore, is an intriguing immunostimulatory cytokine69. In a murine model of poly microbial sepsis, Inoue et al showed decreased splenic cell apoptosis in septic mice treated with IL-1570, and, in mice with poly microbial sepsis treated post-operatively with IL-15, three-fold improvement in survival rate. Similarly improved survival rate was found in mice undergoing the P. aeruginosa pneumonia model70. Treating sepsis with IL-15 has not been attempted in human clinical trial, but IL-7, an immune stimulatory cytokine with effects similar to IL-15, is currently being used as a therapy for hepatitis C, HIV, and cancer patients17.

The immunosuppressed state that characterizes severe trauma or sepsis is also associated with increased suppressor cell populations. The best described are CD4+ and CD8+ T regulatory cell populations (Tregs), popularized by Sagakuchi et al71. Evidence now suggests that naturally occurring Tregs play a major role in suppressing immune reactivity in many diseases72. In addition to naturally occurring Tregs, there are inducible populations that have immunoregulatory functions, including TGF-β producing TH3 cells involved in oral tolerance, and IL-10 producing Treg type 1 (TR1) cells73. Many cell surface molecules serve as markers that are co expressed on Tregs, including glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor (GITR) and intracellular CTLA-466–68. Other factors contribute to development and activity of regulatory cells, such as the forkhead box transcription factor, Foxp3, and TLRs, which recognize PAMPs or can augment Treg function or proliferation74. Treatment of mice with an agonist antibody to GITR has been shown to both suppress Treg function and to stimulate T effector cell function, resulting in increased poly microbial sepsis survival rate 60.

Monneret et al was first to report that sepsis increases the relative number of Tregs in the blood of septic patients75. We reported a relative increase in Tregs in a murine model of polymicrobial sepsis, and that their suppressor activity was markedly increased76. Their importance to outcome remains controversial. Ayala et al and we have not shown any impact on outcome when these populations were deleted in sepsis76, 77, but Oppenheim et al reported improved survival rate in septic mice when Tregs were depleted78. Recently, Nascimento et al showed increased presence of Tregs in thymus and spleen after poly microbial sepsis, and that this increased presence was associated with decreased proliferation of CD4+ T cells79. The sepsis surviving mice were subjected to secondary infection with a non lethal dose of L. pneumophila at 15 and 30 days post sepsis. The mice did not survive, thus leading to a conclusion that the sepsis surviving mice suffered from immune dysfunction. This effect was reversed by treatment with DTA-179.

After decades of failure of clinical trials of therapies to quell early proinflammation induced by sepsis or SIRS, there is intriguing evidence that therapies to restore immune competence by targeting reversal of macrophage and T-cell dysfunction may offer an attractive alternative approach. Only clinical trials will show whether adaptive immunity stimulants for the treatment of immune suppression may have more success than anti-inflammatory approaches17.

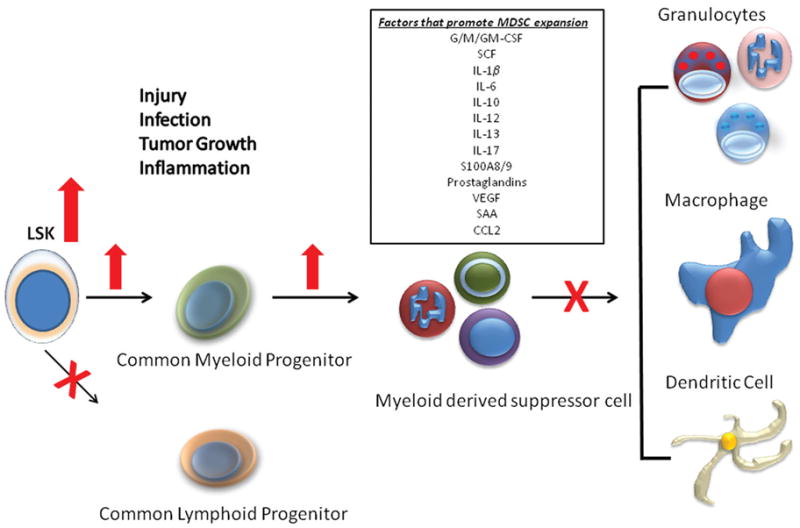

Emergency myelopoiesis drives persistent immunosuppresion and inflammation

The concept that the early inflammatory (SIRS) response to severe trauma or systemic infection is short lived and transient is fallacious. We now recognize that in severe trauma and sepsis patients, inflammation and immune suppression are proceeding concurrently for prolonged periods. Following the initial insult, granulocytes in the bone marrow rapidly demarginate and follow chemokine gradients to the site of infection or injury80. Emptying the bone marrow, combined with dramatic lymphocyte apoptosis in secondary lymphoid organs, creates space for hematopoietic progenitor production81, and production is skewed toward myelopoietic precursors that can differentiate into mature granulocytes, macrophages, or dendritic cells51, 82 (Figure 4). This is a well conserved response to inflammation, and has been termed ’emergency myelopoiesis - granulopoeisis’81–83. Mediators that may drive this response include growth factors (e.g. G/GM-CSF) and cytokines (e.g. IL-6 and IL-17) produced during the early SIRS response84–86.

Emergency myelopoiesis and expansion of the MDSC population in sepsis Changes in the early populations of hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitors, the progenitors for MDSCs are shown. Although expansion of the MDSC population can be explained in part by increased myelopoiesis, defects in the maturation and differentiation of these populations also contribute to its expansion and MDSCs immature phenotype. Reprinted with permission from Molecular Medicine83.

One of the surprising results of emergency myelopoiesis is the emergence of myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in bone marrow, secondary lymphoid organs and even in organs of the reticuloendothelial system. MDSCs, originally noted for their immunosuppressive functions, including ability to suppress T-cell responses via increased production of iNOS, arginase (ARG), and ROS, are a heterogeneous population of activated immature myeloid cells with immune suppressive functions87. We have shown that the increased expansion of MDSC populations is proportional to the severity of the inflammatory insult. Moderate trauma (midline laparotomy) induces a transient increase that persists for days, and more severe insult models (sepsis and burn) cause increase of MDSC population that persist for weeks to months51, 88.

The contribution that MDSCs play in sepsis is controversial, although we believe that they play a central, but still unproven role, in the persistent inflammation of human sepsis, trauma, and the development of PICS. MDSCs, unlike terminally differentiated macrophages, express low concentrations of MHC-II and CD80/CD86, making them poor antigen presenting cells51. However, these MDSCs, unlike terminally differentiated macrophages and monocytes after sepsis or trauma, produce large amounts of IL-10, TNFα, RANTES, MCP1, SDF-1 and MIP1α51,89, 90, 91. These cells also consume large quantities of arginine, producing NO, reactive oxygen species, and peroxynitrites that are both proinflammatory and immunosuppressive. Murine models have shown dramatic MDSC proliferation in bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes of mice surviving more than three days, and, ten days after onset of sepsis, marked splenomegaly and 40% of spleen and 90% of bone marrow cells are MDSCs with persistence beyond 12 week51. Failure to expand the MDSC population was associated in worsened outcomes51, 83. Surprisingly, prevention of expansion of MDSC population has been shown to be detrimental to survival from sepsis and burn. MDSCs appear to be critical for maintenance of innate immunity and inflammatory responses to secondary infection81, 83.

Importantly, expansion of MDSC populations in sepsis can also explain some of the immunosuppression seen in patients with PICS. MDSCs also play a widely recognized role in T cell suppression, in part through nitrosylation of the T cell receptor and depletion of intracellular arginine51, and in promotion of Treg cell production92 (Table 2). As a result, the role that MDSCs have in sepsis is neither simple nor clear cut. Although MDSCs are a component of emergency myelopoiesis and contribute to immune surveillance against secondary infections, their presence in the septic host may also be detrimental by promoting adaptive immunosuppression and persistent inflammation.

Table 2

Functional properties of MDSCs

| Pathologic process | Mechanism /function | |

|---|---|---|

| Upregulated MDSC function | ||

Arginase (ARG) Arginase (ARG) | Cancer | L-arginine depletion and NO scavenging |

Inducible nitric oxide synthetase Inducible nitric oxide synthetase | Cancer | L-arginine depletion and bactericidal |

NADPH oxidase NADPH oxidase | Cancer | ROS/RNS production, nitrosylation of TCR, and bactericidal |

M-CSF R(CD115) M-CSF R(CD115) | Cancer | Associated with suppressive activity |

IL-4rα(CD124) IL-4rα(CD124) | Cancer | Th2 skewing and associated with suppressive activity |

| Proinflammatory cytokines | ||

IL-1β IL-1β | Cancer | Inflammation |

TNF-α TNF-α | Cancer, Sepsis | Inflammation |

LTA4H LTA4H | Cancer | Inflammation |

MIP-1β MIP-1β | Sepsis | Inflammation; chemokine |

CXCL10 CXCL10 | Cancer | Inflammation; chemokine |

RANTES RANTES | Sepsis | Inflammation; chemokine |

| T-helper cell 2 skewing/antiinflammatory cytokines | ||

IL-10 IL-10 | Sepsis | Antiinflammatory; Inhibits T-cell responses; causes TRC expansion |

IL-13 IL-13 | Cancer | Th2-polarizing cytokine |

| Immunosuppression | ||

Direct antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell anergy Direct antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell anergy | Cancer | MHC restricted dissociation of CD3ζ/TCR signaling |

Indirect antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell anergy Indirect antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell anergy | Cancer | ARG, ROS, iNOS |

Indirect antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell anergy Indirect antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell anergy | Cancer | ARG |

TRC expansion TRC expansion | Cancer | CD40, IL-10 |

Suppression of graft-versus-host disease Suppression of graft-versus-host disease | Cancer | IL-10 and TCR activation |

| Protection against infection | ||

Protection against primary infection Protection against primary infection | Sepsis | Regulation of innate inflammation |

Protection against secondary infection Protection against secondary infection | Burn | Increases PMNs and inflammatory monocytes |

Modified with permission from Molecular Medicine83

Designation of Persistent Inflammation/Immunosuppression Catabolism Syndrome (PICS)

With patterns of MOF evolving, our traditional definitions of immunological status are becoming obsolete. Successful management of SIRS in ICUs has increased numbers of patients who reside in ICUs for weeks with a syndrome of moderate organ dysfunction, secondary infection, requirement for life support, and progressive protein catabolism, commonly resulting in loss of lean body mass, and failure to regain strength. Successful management of these patients is commonly defined as discharge to a LTAC, rather than return to a functional life. As fewer patients are developing late MOF, we now observe the emergence of this new syndrome, PICS, and are presented with the challenge of managing simultaneous chronic inflammation and adaptive immunosuppression, protecting against secondary nosocomial infection, and preventing severe protein catabolism (Figure 5). The designation of PICS, acknowledges the presence of multiple immunological and physiological defects that occur simultaneously, and that likely require multimodal therapy.

After the initial, simultaneous SIRS-CARS responsse, many patients linger in the ICU with manageable organ dysfunctions, but do not meet established criteria for late MOF. Clinically, these patients exhibit ongoing protein catabolism with poor nutritional status, poor wound healing and recurrent infections. Additionally, they have persistent low grade inflammation with defects in innate and adaptive immunity including macrophage paralysis, persistent increased MDSC populations, and decreased effector T cell number and function. These patients are ultimately discharged to long term acute care (LTAC) facilities, rarely rehabilitate or return to functional life and usually suffer prolonged decline and indolent death.

PICS patients can be identified in the critically ill surgical intensive care population with prolonged stay time and routine ICU and clinical laboratory measurements. As shown in Table 3, a patient meets PICS criteria if residing in the ICU for at least 10 days and having persistent inflammation defined by C-reactive protein concentration >150 μg/dl and retinol binding protein concentrations < 10 μg/dl, immunosuppression crudely defined by a total lymphocyte count < 800/mm3, and a catabolic state defined by serum albumin concentrations < 3.0 gm/dl, creatinine height index < 80%, and weight loss > 10% or BMI < 18 during the current hospitalization. Although these clinical markers are not direct measurements of inflammation, immunosuppression or protein catabolism, they can serve as surrogates that are readily available in most critical care settings.

Table 3

| Clinical Determinants of PICS

| Research or Laboratory Methodologies

|

|---|---|

|

|

Fortunately, research approaches to better characterize the immune suppression and chronic inflammation associated with critical illness are becoming more and more routine. Rapid ELISA and Luminex™ techniques are making plasma protein, including cytokines such as IL-6, IL-10, IL-1ra and sTNFRI, routine assessments for the inflammatory status of the patients. Procalcitonin is in regular clinical use in Europe, and is becoming more popular in the U.S. Flow cytometric analyses, which were once limited exclusively to large research laboratories are appearing regularly in the clinical setting, making phenotyping of cell populations much more routine. Characterization of the “paralyzed monocyte” by looking at HLA-DR or CD80/CD86 expression on CD14+ cells is now routine93, as is identification of T-cell suppressor molecules, PD1, CTLA-4, BTLA and HVEM on CD4+ and CD8+ cell populations65. Even description of the elusive MDSC is becoming possible with cell sorting techniques that can isolate sufficient cells for not only ARG1 and NOS2 expression, but also antigen-specific cell suppression assays94. The ‘Glue Grant’ has shown the ability to perform genome-wide expression routinely on enriched subsets of leukocyte populations95, 96, and determine genomic expression patterns associated with different clinical outcomes19, 97.

Clinical relevance and medical management

Combating MOF has been a major ICU challenge for the past 40 years. Management strategies have continued to evolve to address different MOF phenotypes and prevent or minimize their fatal expression. Through improved, aggressive initial care, today’s patients survive previously lethal insults, be it severe sepsis, trauma or surgical injury, do not develop late MOF, and do not die in the ICU. Unfortunately, many who survive their initial ICU days do not progress to normal recovery, but for undetermined reasons, persist with manageable organ dysfunctions, catabolism, poor nutritional status, and recurrent infections, only to be discharged to LTACs, subsequent ICU readmission, or indolent death. We believe that this state, termed ‘PICS,’ is the predominant pathology that prolongs intensive care and is the new phenotype that has replaced late appearing MOF.

Unfortunately, when PICS is recognized, course correction is difficult, and rehabilitation of these patients into a functional state is rare. The major challenge(s) for this new paradigm are: (1) to identify PICS early in its course, (2) to understand its underlying pathophysiology, and (3) to initiate appropriate multi-modal therapies that target specific components of the syndrome. We would argue that identification of PICS, as well as the development of therapeutic interventions will be best performed from a platform of optimized care derived from evidence-based guidelines for patient management, available with CCDS98, 99.

Medical care resource consumption associated with PICS has yet to be measured, but is likely going to be a large multiple of the costs associated with the acute treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. More discouraging, the incidence of PICS is likely to increase as our population ages and our technology improves. Characterization and management of PICS will require new technologies for direct monitoring, and where necessary, modulation of the patient’s individual nutritional status and immune responses. Management of PICS should capitalize on available evidence-based guidelines and computer based technology to implement guidelines at the bedside. Multicenter clinical trials in well characterized patient populations with standardized care will require multiple collaborating clinical centers of expertise. We suggest that PICS is the new horizon for surgical intensive care.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) grants R01 GM-040586-23, R01 GM-081923-05,. T32 GM-006311-13 (LFG, AGC) and F32 GM-093665-01 (ACG).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: No conflict of interests have been declared.

Author Contributions

LFG contributed to the composition, drafting, and editing of the manuscript.AGC contributed to the composition of the manuscript

PAE contributed the editing/drafting of the manuscript

DA contributed to the editing/drafting of the manuscript.

BAM contributed to the manuscript concept, design and editing.

LLM contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript, and the composition/editing of the manuscript.

FAM contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript, and the composition/editing of the manuscript.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0b013e318256e000

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3705923?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1097/ta.0b013e318256e000

Article citations

Impact of thyroid hormones on predicting the occurrence of persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome in patients with sepsis.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 15:1417846, 16 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39479266 | PMCID: PMC11521835

Lactate's impact on immune cells in sepsis: unraveling the complex interplay.

Front Immunol, 15:1483400, 20 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39372401 | PMCID: PMC11449721

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Into the storm: the imbalance in the yin-yang immune response as the commonality of cytokine storm syndromes.

Front Immunol, 15:1448201, 10 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39318634 | PMCID: PMC11420043

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Optimal Timing of PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Protects Organ Function During Sepsis.

Inflammation, 23 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39174864

Evaluating the Therapeutic Efficiency and Efficacy of Blood Purification for Treating Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Single-Center Data Based on Propensity Score Matching.

Int J Gen Med, 17:3765-3777, 29 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39224690 | PMCID: PMC11368098

Go to all (403) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Relationship of systemic inflammatory response syndrome to organ dysfunction, length of stay, and mortality in critical surgical illness: effect of intensive care unit resuscitation.

Arch Surg, 134(1):81-87, 01 Jan 1999

Cited by: 101 articles | PMID: 9927137

[A retrospective clinical study of sixty-three cases with persistent inflammation immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome].

Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi, 55(12):941-944, 01 Dec 2016

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 27916049

The evolution of nutritional support in long term ICU patients: from multisystem organ failure to persistent inflammation immunosuppression catabolism syndrome.

Minerva Anestesiol, 82(1):84-96, 20 Feb 2015

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 25697882

Review

Causes and consequences of fever complicating critical surgical illness.

Surg Infect (Larchmt), 5(2):145-159, 01 Jan 2004

Cited by: 49 articles | PMID: 15353111

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIGMS NIH HHS (9)

Grant ID: F32 GM093665

Grant ID: R01 GM-081923-05

Grant ID: F32 GM-093665-01

Grant ID: T32 GM008721

Grant ID: R01 GM040586

Grant ID: R01 GM081923

Grant ID: K23 GM087709

Grant ID: T32 GM-006311-13

Grant ID: R01 GM-040586-23