Abstract

Free full text

RELIEF OF PROFOUND FEEDBACK INHIBITION OF MITOGENIC SIGNALING BY RAF INHIBITORS ATTENUATES THEIR ACTIVITY IN BRAFV600E MELANOMAS

Associated Data

SUMMARY

BRAFV600E drives tumors by dysregulating ERK signaling. In these tumors, we show that high levels of ERK-dependent negative feedback potently suppress ligand-dependent mitogenic signaling and Ras function. BRAFV600E activation is Ras-independent and it signals as a RAF-inhibitor sensitive monomer. RAF inhibitors potently inhibit RAF monomers and ERK signaling, causing relief of ERK-dependent feedback, reactivation of ligand-dependent signal transduction, increased Ras-GTP and generation of RAF inhibitor-resistant RAF dimers. This results in a rebound in ERK activity and culminates in a new steady state, wherein ERK signaling is elevated compared to its initial nadir after RAF inhibition. In this state, ERK signaling is RAF inhibitor resistant, and MEK inhibitor sensitive, and combined inhibition results in enhancement of ERK-pathway inhibition and antitumor activity.

INTRODUCTION

ERK signaling plays an important role in regulating pleiotypic cellular functions. Activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), causes Ras to adopt an active, GTP-bound conformation (Downward, 2003) in which it induces the dimerization and activation of members of the RAF kinase family (Wellbrock et al., 2004a). Activated RAF phosphorylates and activates MEK1/2; these phosphorylate and activate ERK1/2, which regulate cellular function by phosphorylating multiple substrates. A complex network of negative feedback interactions limits the amplitude and duration of ERK signaling. Negative feedback is mediated directly by ERK-dependent inhibitory phosphorylation of components of the pathway, including EGFR, SOS and RAF (Avraham and Yarden, 2011; Dougherty et al., 2005; Douville and Downward, 1997). In addition, ERK activation induces the expression of proteins that negatively regulate the pathway, including members of the Sprouty (Spry) and dual specificity phosphatase (DUSP) families (Eblaghie et al., 2003; Hanafusa et al., 2002).

ERK activation is a common feature of tumors with KRas, NRas or BRAF mutation, or dysregulation of RTKs (Solit and Rosen, 2011). Tumors with BRAF mutation and some with RAS mutation are sensitive to MEK inhibitors (Sebolt-Leopold et al., 1999; Leboeuf et al., 2008; Pratilas et al., 2008; Solit et al., 2006). However, these drugs inhibit ERK signaling in all cells, and toxicity to normal tissue limits their dosing and their therapeutic effects (Kirkwood et al., 2012).

ATP-competitive RAF inhibitors have also been developed (Bollag et al., 2010). The biologic effects of MEK inhibitors and RAF inhibitors in BRAFV600E melanomas are similar. However, RAF inhibitors effectively inhibit ERK signaling only in tumors with mutant BRAF (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010; Heidorn et al., 2010; Joseph et al., 2010; Poulikakos et al., 2010). In cells with wild-type (WT) BRAF, Ras activation supports the formation of Ras-dependent RAF dimers. Binding of RAF inhibitors to one protomer in the dimer allosterically transactivates the other and causes activation of ERK-signaling in these cells (Poulikakos et al., 2010). We hypothesized that, in BRAFV600E tumors, levels of Ras activity are too low to support the formation of functional dimers, so that BRAFV600E is primarily monomeric and inhibited by the drug. This mutation-specific pathway inhibition by the drug gives it a broad therapeutic index and likely accounts for its remarkable antitumor effects in melanomas with BRAF mutation (Chapman et al., 2011; Sosman et al., 2012). In support of this model, acquired resistance to RAF inhibitors is due to lesions that increase Ras activity, e.g., NRAS mutation or RTK activation (Nazarian et al., 2010), and to aberrantly spliced forms of BRAFV600E that dimerize in a Ras-independent manner (Poulikakos et al., 2011).

We have now endeavored to test the hypothesis that the levels of Ras activity in BRAFV600E melanomas are too low to support significant expression of active RAF dimers and to elucidate the mechanism underlying this phenomenon and its biologic and therapeutic consequences.

RESULTS

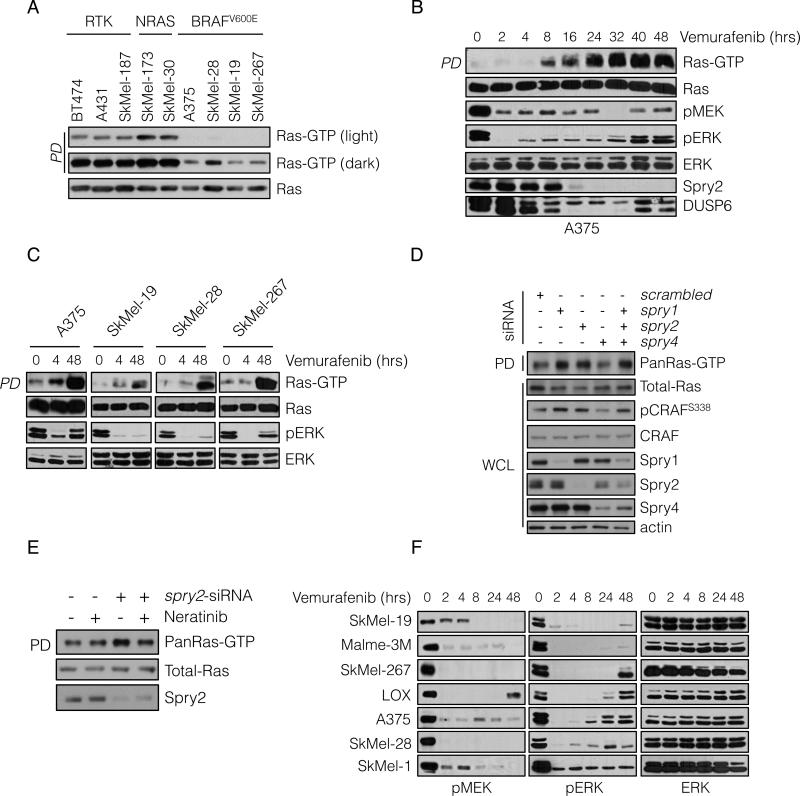

In BRAFV600E melanomas Ras activation is suppressed by ERK-dependent feedback

Assessment of BRAFV600E melanoma cells confirmed that they have low levels of GTP-bound Ras (Figure 1A and S1A). As expected, Ras-GTP levels were most elevated in tumor cells with mutant Ras and were lower in cells in which ERK signaling is driven by RTKs. Ras-GTP levels were significantly lower in melanoma cell lines harboring BRAFV600E, and could be detected only when immunoblots were overexposed (Figure 1A).

(A) Whole cell lysates (WCL) from the indicated cell lines were subjected to pull-down (PD) assays with GST-bound CRAF Ras-binding domain (RBD). WCL and PD products were immunoblotted (IB) with a pan-Ras antibody.

(B, C) BRAF-mutated melanoma cell lines were treated with vemurafenib (2 μM) for the indicated times. Ras-GTP was detected as in A. Phospho- and total levels of ERK pathway components were assayed by IB.

(D) A375 cells (BRAFV600E) were transfected with siRNA pools targeting the indicated Spry isoforms or scrambled oligonucleotides. WCL were subjected to GST-RBD PD and analyzed by IB for the indicated proteins.

(E) A375 cells were transfected with spry2 siRNA and 48 hrs after transfection they were treated with neratinib (1μM) for 1 hr. Ras-GTP levels were determined as above.

(F) BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines were treated with vemurafenib (2 μM) for various times. The effect on ERK signaling is shown. See also Figure S1.

We investigated whether low Ras activity is due to high levels of ERK signaling. We have shown that ERK-dependent transcriptional output is markedly elevated in BRAFV600E melanomas (Joseph et al., 2010; Pratilas et al., 2009) and includes Spry proteins, which suppress the activation of Ras by various RTKs. This suggests that ERK-dependent feedback inhibition of receptor signaling causes suppression of Ras activation in these tumors. Pharmacologic inhibition of RAF or MEK led to induction of Ras-GTP to varying degrees in BRAFV600E tumors (Figure 1B, 1C and S1B); with induction beginning 4-8 hours after drug addition and reaching a steady state 24 hours after pathway inhibition (Figure 1B). Although marked induction of Ras-GTP occurred, levels remained significantly lower than those observed in tumor cells with EGFR activation (Figure S1C). These findings show that ERK dependent feedback suppresses Ras activity in BRAFV600E melanomas and are consistent with the idea that BRAFV600E signals in a Ras-independent manner.

Induction of Ras-GTP correlated with decreasing levels of Spry proteins and the ERK phosphatase DUSP6 (Figure 1B and S1C). Spry proteins inhibit RTK signaling, in part by binding to Grb2 and sequestering the Grb2:SOS complex so it cannot bind RTKs (Kim and Bar-Sagi, 2004; Mason et al., 2006). In BRAFV600E melanomas, Spry1, 2 and 4 are overexpressed in an ERK-dependent manner (Figure S1D). To determine whether Spry overexpression contributes to feedback inhibition of Ras, we knocked down the expression of Spry1, 2 and 4 with siRNAs and Ras-GTP was assessed 48 hours later. Downregulation of either Spry1 or Spry2 increased total (pan) Ras-GTP levels, whereas knockdown of Spry 4 had no effect. Spry2 knockdown resulted in induction of HRas, NRas and KRas-GTP, while Spry1 and 4 downregulation appeared to induce HRas-GTP alone (Figure 1D, S1E and data not shown). Knockdown of all three isoforms did not result in greater induction of Ras-GTP than knockdown of Spry2 alone (Figure 1D and S1E). Induction of Ras-GTP in these cells was associated with increased phosphorylation of CRAFS338, a modification associated with CRAF activation. These data suggest that ERK-dependent feedback inhibition of Ras activation is mediated, in part, by expression of Spry proteins.

We hypothesized that Spry proteins block activation of Ras by interfering with RTK signaling. Since A375 melanoma cells express EGFR and respond to its ligands (see below), we tested whether the effect of Spry2 knockdown was reversed by neratinib, an irreversible inhibitor of EGFR/HER kinases. Neratinib had no effect on Ras-GTP in A375 cells, but reduced the Ras-GTP increase induced by Spry2 knockdown (Figure 1E). This supports the idea that ERK-dependent expression of Spry2 blocks RTK-dependent activation of Ras.

Induction of Ras-GTP by RAF inhibitors is accompanied by a rebound in phospho-ERK

Increased Ras-GTP should be accompanied by an increase in RAF inhibitor-resistant RAF dimers and a concomitant increase in pERK and ERK signaling. After initial inhibition of ERK phosphorylation in seven BRAFV600E melanomas treated with the RAF inhibitor, we observed a pronounced rebound in four cell lines, and a more marginal rebound in two others (Figure 1F). The pERK rebound was also elicited by dabrafenib, a more potent RAF inhibitor (Figure S1F). The rebound was preceded by loss of ERK-dependent inhibitory phosphorylation of CRAF at S289, S298 and S301 and was associated with an induction of the CRAF S338 activating phosphorylation and a slight induction of pMEK, detected in A375 cells (Figure S1F and S1G) but not in all the cell lines.

The rebound in pERK was accompanied by increased expression of genes previously shown to be ERK-dependent in BRAFV600E melanomas (Figure S1H-L). The magnitude of pERK reactivation varied across the melanomas examined, but pERK levels reached a steady state that was maintained for at least seven days (data not shown). The magnitude of ERK reactivation was less pronounced in melanomas than in colorectal and thyroid carcinomas harboring BRAFV600E (J. Fagin, unpublished data)

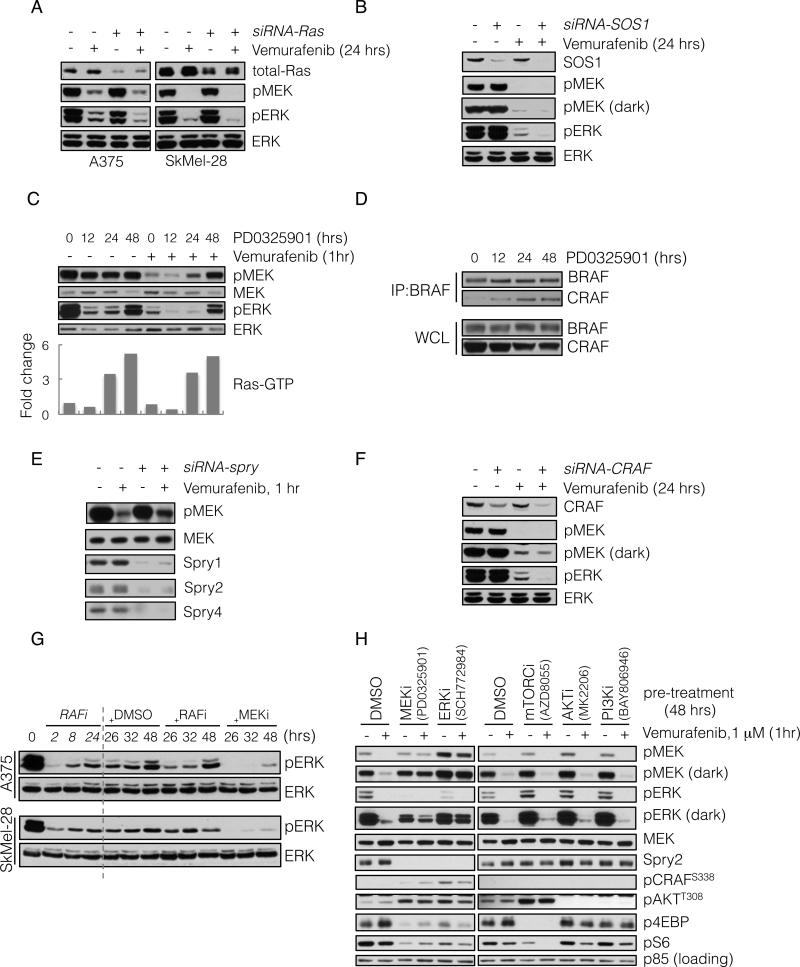

We examined whether pERK rebound required Ras activation. Knockdown of Ras isoforms by siRNA had little effect on baseline pERK, but decreased the residual pERK in A375 and SkMel-28 cells treated with vemurafenib (Figure 2A). These results confirm that ERK signaling is Ras-independent in BRAF-mutated melanomas, but that ERK rebound after RAF inhibition is Ras-dependent. Since activation of WT Ras requires exchange factor activity, we asked whether rebound required SOS1, a Ras-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor that is inhibited by Spry (Nimnual and Bar-Sagi, 2002). Downregulation of SOS1 in A375 cells diminished pERK rebound after inhibition with vemurafenib without affecting baseline pERK (Figure 2B).

(A) BRAFV600E expressing A375 and SkMel-28 cells were transfected with siRNA pools targeting all three Ras isoforms (+) or scrambled oligonucleotides (-). 48 hours after transfection the cells were treated with vemurafenib (2 μM) for 24 hours and analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) to detect the indicated proteins.

(B) A375 cells were transfected with siRNA pools targeting SOS1. 48 hours after transfection the cells were treated with vemurafenib (2 μM) for 24 hours, and analyzed by IB as above.

(C) A375 cells were untreated or initially pre-treated with MEK inhibitor PD0325901 (50 nM) for the times shown. Subsequently, vemurafenib (1 μM) was added for 1 hour. WCL were assayed to determine changes in pMEK and pERK. WCLs were also analyzed with a GST-RBD Elisa assay. The fold change in the amount of GTP-bound Ras, as compared to untreated cells, is shown.

(D) BRAFV600E expressing Malme-3M cells were treated with PD0325901 (50 nM) for various times. To assess BRAF-CRAF dimerization, WCL were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with a BRAF-specific antibody and then IB for CRAF.

(E) A375 cells were transfected with siRNA pools targeting spry1-4 genes. After 48 hrs they were treated with vemurafenib (1 μM) for 1 hr. WCL were analyzed to determine changes in inhibition of MEK phosphorylation.

(F) A375 cells were transfected with CRAF siRNAs and subsequently treated with vemurafenib for 24 hours. Changes in phospho- and total ERK are shown.

(G) BRAFV600E expressing cell lines were initially treated with vemurafenib (1 μM) for 2, 8 and 24 hours. After 24 hours of treatment, DMSO, vemurafenib (1 μM, RAFi) or PD0325901 (5 nM, MEKi) was added for an additional 2, 8 and 24 hours respectively. The total treatment time is indicated. The effect on ERK signaling is shown.

(H) A375 cells were pre-treated with inhibitors targeting the indicated kinases for 48 hrs, followed by treatment with vemurafenib for 1 hr. WCL were analyzed to detect the ability of vemurafenib to inhibit MEK phosphorylation by RAF, as well as the ability of the indicated compounds to inhibit their targets. Their effects on Spry2 and pCRAF are also shown. See also Figure S2.

ERK rebound is dependent on expression of CRAF-containing dimers that are resistant to RAF inhibition

Our data suggest that relief of ERK-dependent feedback inhibition of Ras activity diminishes the effect of RAF inhibitors. To support this idea, we asked whether MEK inhibitors increase Ras activation and cause resistance to RAF inhibitors. The MEK inhibitor (PD0325901) inhibited ERK phosphorylation and induced Ras-GTP levels within 24 hours of addition (Figure 2C and S1B). With this in mind, we asked if relief of feedback by MEK inhibitors affected vemurafenib inhibition of MEK phosphorylation. Vemurafenib treatment for one hour potently inhibited pMEK in untreated BRAFV600E melanomas and in those cells exposed to the MEK inhibitor for up to 12 hours, at which time Ras-GTP had not increased appreciably (Figure 2C). After 24 and 48 hours of exposure, however, Ras-GTP was induced and inhibition of pMEK by the RAF inhibitor was much less effective (Figure 2C, S2A-C). Similar results were achieved with different MEK (trametinib) and RAF (dabrafenib) inhibitors (Figure S2B).

These data support the idea that relief of ERK-dependent feedback increases the level of Ras-dependent RAF dimers. This turned out to be the case. As measured by co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins, the MEK inhibitor increased CRAF:BRAF dimers at times that correlated with induction of Ras-GTP and RAF inhibitor resistance (12-48 hours, Figure 2D and S2C).

Spry proteins suppressed RTK-induced Ras activation in BRAFV600E-melanomas. We asked if Spry expression was required for maximal inhibition of RAF. In A375 melanoma cells, knockdown of Spry1-4 reduced the degree of acute inhibition of MEK phosphorylation by vemurafenib (Figure 2E). A similar result was obtained when Spry2 was knocked down alone (Figure S2D). These findings suggest that Spry overexpression contributes to maximal RAF inhibition in BRAF-melanomas.

If formation of RAF dimers is responsible for rebound in ERK phosphorylation in tumors treated with RAF inhibitors, ERK rebound should be CRAF dependent. As previously shown (Hingorani et al., 2003; Wellbrock et al., 2004b), knockdown of CRAF expression had no effect on ERK signaling in A375 cells (Figure 2F). In contrast, in tumors treated with RAF inhibitors, residual pERK was significantly reduced when CRAF expression was reduced by siRNA (Figure 2F).

Together, these data suggest that relief of ERK-dependent feedback by MEK or RAF inhibitors induces Ras-GTP and the formation of CRAF-containing dimers that are insensitive to the RAF inhibitor. If ERK-rebound is driven by these dimers, it should be sensitive to MEK inhibitors, but not to RAF inhibitors (Poulikakos et al., 2010). We tested this assertion in BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines treated with vemurafenib (Figure 2G). In these cell lines, vemurafenib caused maximal inhibition of pERK within two hours of inhibition, and rebound occurred within eight hours. ERK-rebound was insensitive to re-treatment with vemurafenib, 24 hours after the initial treatment, but was sensitive to MEK inhibition. Similar findings were observed when the experiment was repeated with the other MEK and RAF inhibitors (Figure S2E). These data support the idea that relief of ERK-dependent feedback leads to a rebound in pERK and a new steady state in which the pathway is driven by RAF dimers that are insensitive to RAF inhibition.

Our data show that relief of feedback inhibition of Ras is necessary for induction of ERK rebound. Overexpression of the ERK phosphatase DUSP6 is a property of BRAFV600E melanomas and rapidly decreases after RAF inhibition. We asked whether downregulation of DUSP6 also contributed to ERK-rebound. A375 cells were transfected with DUSP6 specific siRNAs and then treated with vemurafenib. Knocking down DUSP6 resulted in increased residual pERK following RAF inhibition, without significant differences in residual pMEK (Figure S2F). This suggests the decrease in DUSP6 expression plays a permissive role in pERK rebound following RAF inhibition.

We asked if relief of PI3K or mTOR pathway feedback also affected inhibition of MEK phosphorylation by vemurafenib. A375 cells were treated with selective inhibitors of MEK, ERK, mTOR kinase, AKT or PI3K for 48 hrs, followed by treatment with vemurafenib to assess inhibition of MEK phosphorylation by RAF. Inhibiting MEK or ERK, prevented inhibition of MEK phosphorylation by vemurafenib. This was associated with loss of Spry2 expression and induction of CRAFS338 (Figure 2H). Inhibition of PI3K, AKT or mTOR kinase did not affect sensitivity to vemurafenib, Spry2 expression or pCRAF. The mTOR kinase inhibitor did not affect vemurafenib inhibition even though it relieved feedback inhibition of signaling to pAKTT308. Thus, maximal effectiveness of RAF inhibitors specifically requires intact ERK-dependent feedback.

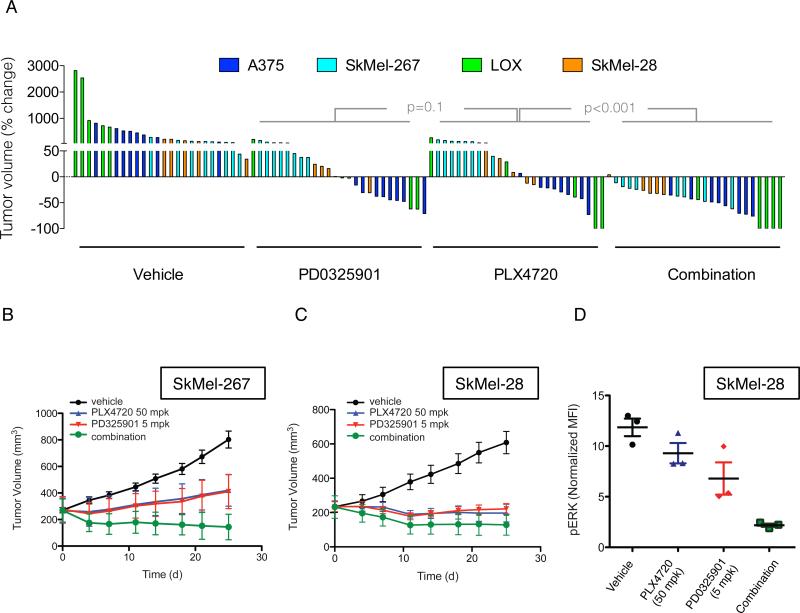

Inhibition of ERK rebound with MEK inhibitors enhances the suppression of ERK output and tumor growth by RAF inhibitors

Since ERK phosphorylation and output were reactivated in a MEK-dependent manner in tumors exposed to RAF inhibitors, we examined whether concurrent RAF and MEK inhibition resulted in better inhibition of the pathway and tumor growth. As compared to treatment with either agent alone (Figure S3A), ERK phosphorylation was inhibited to greater degree in BRAFV600E melanomas exposed to vemurafenib and a low concentration of PD0325901 (5nM). The combination of dabrafenib and trametinib also inhibited the growth of A375 cells in culture better than either drug alone (Figure S3B).

We tested the effectiveness of combining RAF and MEK inhibitors in vivo in four BRAFV600E melanoma mouse xenograft models (Figure 3A). These experiments were done with an effective dose (12.5mg/kg) of PLX4720, which is closely related to vemurafenib but easier to formulate (Tsai et al., 2008), and a low dose (2mg/kg) of PD0325901. Each inhibitor was effective alone (Figure 3A), with regression observed in approximately 50% of animals in either arm. In contrast, combined therapy caused regression of all but one tumor (25/26). Figures S3C-F show tumor responses over four weeks of treatment. The combination of RAF and MEK inhibitors was effective in SkMel-28 and SkMel-267 xenografts (Figure S3C-D). In A375 and LOX xenografts, (Figure S3E-F), the addition of MEK inhibitor did not significantly improve tumor growth inhibition initially, but did delay tumor regrowth following prolonged treatment.

(A) Mice bearing xenografts from four different BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines were treated with vehicle, PD0325901 (2 mg/kg), PLX4720 (12.5 mg/kg) or their combination for four weeks. A waterfall representation of the best response for each tumor is shown.

(B, C) Mice bearing SkMel-267 (B) and SkMel-28 (C) xenografts were treated with PLX4720 (50 mg/kg) alone or in combination with PD0325901 (5 mg/kg) for the indicated times. The tumor volumes (and SEM) are shown as a function of time after treatment.

(D) Cells derived from SkMel-28 xenografts treated as shown for 48 hrs were subjected to flow-cytometric analysis to measure levels of pERK in isolated human melanoma cells. See also Figure S3.

We repeated the experiment with a higher dose of PLX4720 (50 mg/kg) in SkMel-267 and SkMel-28 xenografts and found that the combination of RAF and MEK inhibition was still superior to either drug alone (Figure 3B-C). Flow-cytometric analysis of tumor-derived cells from SkMel-28 xenografts revealed that more than 50% of ERK remained phosphorylated after single agent inhibition of RAF or MEK alone (Figure 3D). The combination, however, resulted in a near complete ERK inhibition. Taken together, these results suggest that combined inhibition of RAF and MEK has enhanced tumor activity and that this is due to more complete inhibition of ERK signaling.

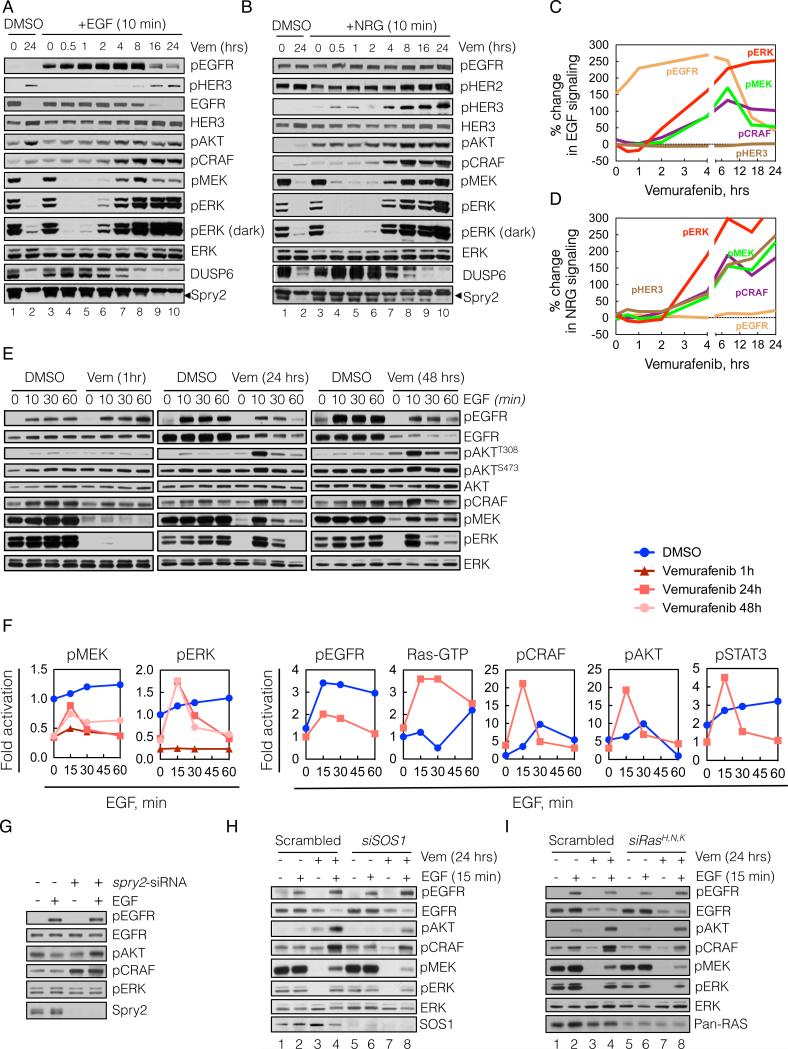

Relief of ERK-dependent feedback potentiates receptor signaling

We hypothesized that elevated ERK-dependent feedback in these cells suppresses mitogenic signaling and causes these cells to be poorly responsive to growth factors. If this is the case, relief of ERK-dependent feedback by inhibitors of ERK signaling should result in increased transduction of the ligand-activated signal. In order to test this hypothesis, we assessed the ability of exogenous ligands to activate signaling in BRAFV600E cells before and after inhibition of ERK signaling with vemurafenib (Figure 4A-D).

(A-D) BRAFV600E expressing A375 cells were treated with vemurafenib (vem, 2 μM) for various times. At the indicated times the cells were stimulated with either EGF (100 ng/mL, A) or NRG (100 ng/mL, B) for 10 min. WCL were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) to assay downstream signaling. The percent change in ligand induced signaling (C, D) was determined by densitometric analysis of the bands in A and B, respectively.

(E, F) A375 cells were untreated (DMSO) or treated with vemurafenib for 1, 24 or 48 hrs in serum free media and then stimulated with EGF for the indicated times. EGF-induced changes in phosphorylation of signaling intermediates were determined by IB (E) and quantified by densitometry (F). Changes in Ras-GTP were measured with an ELISA based GST-RBD assay (shown) and confirmed with a traditional pulldown assay (data not shown).

(G) A375 cells were transfected with spry2 siRNAs, followed by serum starvation for 24 hrs and EGF stimulation for 10 min. WCL were IB with the indicated antibodies.

(H, I) A375 cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting either SOS1 (H) or the three Ras isoforms (I) or scrambled siRNAs. Then, the cells were treated with vemurafenib for 24 hrs in serum-free media, followed by stimulation with EGF for 10 min. The phosphorylation of various signaling intermediates is shown. See also Figure S4.

BRAFV600E melanoma cells have high levels of pMEK and pERK and high levels of expression of DUSP6 and Spry2 (Figure 4A, lane 1). After 24-hours of exposure to vemurafenib (lane 2), pMEK and pERK are quite low, with residual levels of pERK due to rebound. DUSP6 and Spry2 levels are markedly diminished 4-8 hours after drug exposure (lanes 7-10). To assess the ability of an exogenous ligand to activate signaling, we added EGF or NRG at various times after vemurafenib treatment and evaluated signaling 10 minutes after ligand addition (Figure 4A and B, respectively; lanes 3-10). Vemurafenib completely suppressed pMEK and pERK within 30 minutes of treatment and neither ligand appreciably induced pMEK, pERK, pCRAF or pAKT after one hour of RAF inhibition (lane 5). After two hours of RAF inhibition, however, EGF significantly stimulated pMEK and pERK (lane 6). Ligand stimulation of signaling, which we term ‘signalability’, rose markedly after 4 to 8 hours of RAF inhibition (Figure 4A lanes 7-8, and and4C),4C), and was maintained after 24 hours of exposure to the inhibitor (lanes 9-10). A similar profile of ligand-induced signaling was observed when the cells were stimulated with NRG (Figure 4B, lanes 3-10 and and4D).4D). The ability of ligands to induce pMEK and pERK was accompanied by an increase in their induction of CRAF and AKT phosphorylation.

These data show that ligand stimulation of ERK and PI3K signaling in BRAFV600E melanomas is low (i.e. suppressed signalability), but hours after the ERK pathway is inhibited, the transduction of the signal is markedly potentiated (i.e. restored signalability). This could be due to enhanced activation of receptors, enhanced signaling downstream of the activated receptor, or both. Induction of EGFR phosphorylation after exposure to EGF for 10 minutes increased slightly one hour after RAF inhibition, at which time downstream signaling was not activated, and remained essentially constant from 2-8 hours after RAF inhibition (Figure 4A, C). EGFR expression did not change over this time. These findings suggest that enhancement of EGF signalability is due to relief of feedback inhibition of intracellular transduction of the ligand-induced signal. Of note, phospho- and total EGFR decreased significantly 16-24 hours after RAF inhibition, but induction of signaling by EGF was undiminished (Figure 4A, lanes 9-10).

The ability of NRG to induce phosphorylation of HER3 was enhanced 4 hours after RAF inhibition, while a minimal increase was noted in the levels of HER3 protein expression (Figure 4B, D). These results suggest that loss of ERK-dependent feedback potentiates NRG activation of HER3, an event that includes heterodimerization and phosphorylation by other HER kinases.

To test the generality of the phenomenon of increased signalability following RAF inhibition, A375 and SkMel-28 cells were treated with vemurafenib for 24 hours and then stimulated for 10 minutes with EGF, NRG, epiregulin (ERG), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF1) or PDGF (Figure S4A). With the exception of IGF1 and PDGF, the ability of all of other ligands to activate ERK was enhanced by pretreatment with vemurafenib. The effect of RAF inhibition on receptor phosphorylation was complex (Figure S4B). Ligand-induced phosphorylation of EGFR and IGF1R were not appreciably changed after 24 hours of ERK inhibition, whereas phosphorylation of Met was enhanced in SkMel-28 but not in A375 cells. These data show that activation of BRAFV600E suppresses the transduction of signaling from multiple receptors and demonstrate the complexity of the details of this suppression in different tumors.

We characterized in more detail the kinetics of EGF stimulation of signaling in vemurafenib treated A375 cells (Figures 4E-F). ERK is maximally inhibited after one hour of vemurafenib treatment but EGF activation of EGFR did not activate downstream effectors at this time. After 24 and 48 hrs of vemurafenib treatment, however, EGF activates MEK, ERK, AKT, and STAT3 phosphorylation. Induction of effector phosphorylation could be blocked by HER kinase inhibitors or in the case of AKT by inhibition of PI3K (data not shown).

Our data suggest that overexpression of Spry proteins plays a role in suppressing signalability. To test this hypothesis, we determined if knocking down Spry2 in A375 melanomas enabled EGFR signaling. Down-regulation of Spry2 induced pCRAF and increased EGF induction of pAKT (Figure 4G). Spry knockdown, however, did not affect EGFR-induced pERK, consistent with the idea that loss of DUSP6 expression is permissive for this effect. Knockdown of either SOS1 or Ras isoforms decreased the EGF-induced activation of pCRAF, pMEK and pERK after 24 hours of vemurafenib treatment in A375 cells, suggesting that reactivation of ERK signaling requires these proteins (Figure 4H and I, respectively; lanes 8 vs 4). These data support our conclusion that Spry proteins contribute to suppression of signalability by ERK-dependent feedback.

Diverse exogenous ligands reduce the effectiveness of RAF inhibitors

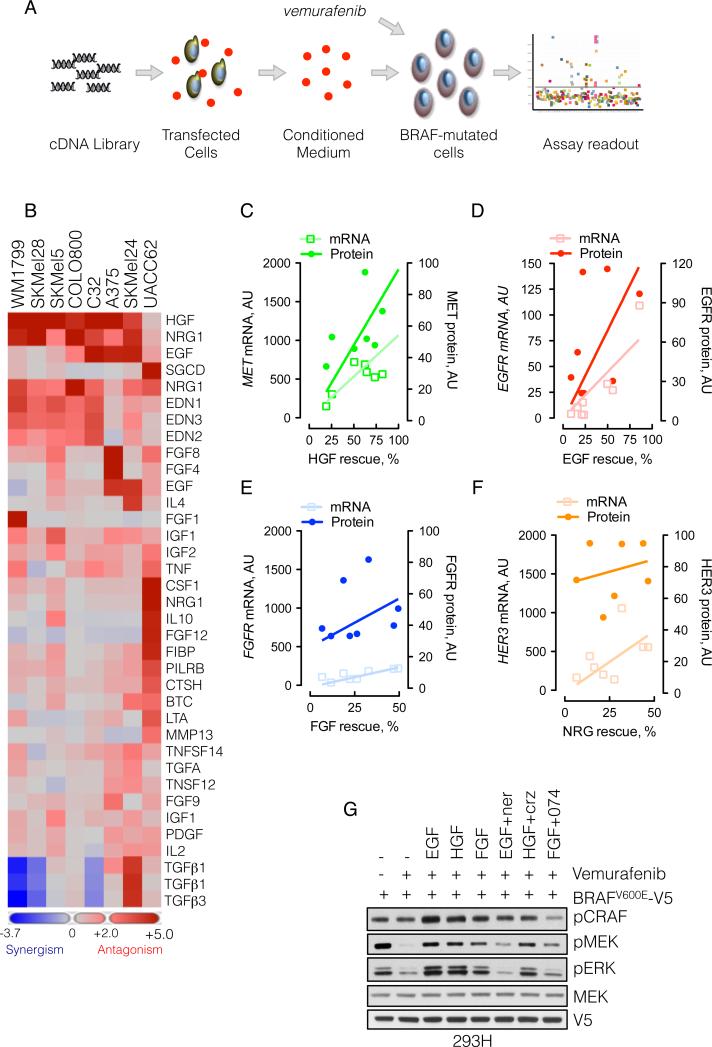

Our data suggest that the response of BRAFV600E melanoma cells to growth factors is limited. In contrast, after RAF inhibitor treatment, the restoration of signalability enables signal transduction from extracellular ligands, a process that is likely to diminish RAF inhibition. To determine which growth factors were capable of attenuating the antiproliferative effects of vemurafenib, we expressed a library of 317 cDNA constructs, encoding 220 unique secreted or single-pass transmembrane proteins in 293T cells (Figure 5A). The media derived from these cultures were added to BRAFV600E melanomas in combination with vemurafenib and the effect on proliferation was assessed. We identified more than five different ligand families (including EGF, HGF, NRG and FGF) that antagonized the vemurafenib sensitivity in one or more of eight BRAFV600E-melanomas tested (Figure 5B and S5A). In contrast, other growth factors, such as PDGF and IGF, had a minimal effect, and some, such as TGFβ, accentuated vemurafenib-induced growth inhibition. A detailed presentation of the assay for the effects of ligands on the proliferation of SkMel-28 cells exposed to vemurafenib is shown in Figure S5B.

(A) Schematic representation of the secretome assay. 293T cells grown in 384-well plates were transfected with a cDNA library encoding 220 unique secreted and single pass transmembrane proteins. Secreted ligands were collected in the conditioned medium, which was combined with vemurafenib (1 μM) and added to melanoma cell lines to assay the effect on proliferation.

(B) Heat map representation of the effect of secreted ligands in the ability of vemurafenib to inhibit growth in a panel of eight BRAFV600E melanomas (some ligands were encoded by multiple cDNAs). Ligands with most potent effects are shown.

(C-D) The percent rescue by the indicated growth factors was plotted as a function of the mRNA and protein level of the respective RTK. The mRNA level was obtained from expression profiling of the indicated lines, whereas the protein level was quantified by immunoblotting (shown in Figure S5C) and densitometry.

(G) 293H cells were transfected with V5-tagged BRAFV600E, followed by treatment with vemurafenib (1 μM, 15 min), alone, and in combination with the indicated ligands and inhibitors (1 μM each) of HER kinases (neratinib), MET (crizotinib) or FGFR (PD173074). The ability of vemurafenib to inhibit MEK phosphorylation is shown. See also Figure S5.

The ability of several ligands to reduce sensitivity to vemurafenib was further validated in A375, SkMel-19, and SkMel-267, in which growth factors increased the vemurafenib IC50 (from less than 2-fold to greater than 5-fold, Figure S5C). In contrast, in SkMel-28 cells, the IC50 increased to greater than 5 μM in the presence of EGF, NRG or HGF.

We attempted to identify factors that determined whether specific ligands (EGF, NRG, FGF, HGF) affected the vemurafenib-response in these cell lines. The attenuation of vemurafenib effect by these growth factors correlated with the level of mRNA and protein expression of their cognate receptors (Figure 5C-F and Figure S5D).

The data in Figure 4 suggest that RTK ligands will decrease RAF inhibition by vemurafenib. To test whether this is the case in a single cellular background, we treated 293H cells expressing BRAFV600E with vemurafenib, in the presence or absence of EGF, HGF and FGF. These growth factors reduced the ability of vemurafenib to inhibit pMEK (Figure 5G), an effect that was reversed by inhibition of the respective RTKs, although the effect of MET inhibitor crizotinib was modest.

HER kinase activity is upstream of ERK rebound

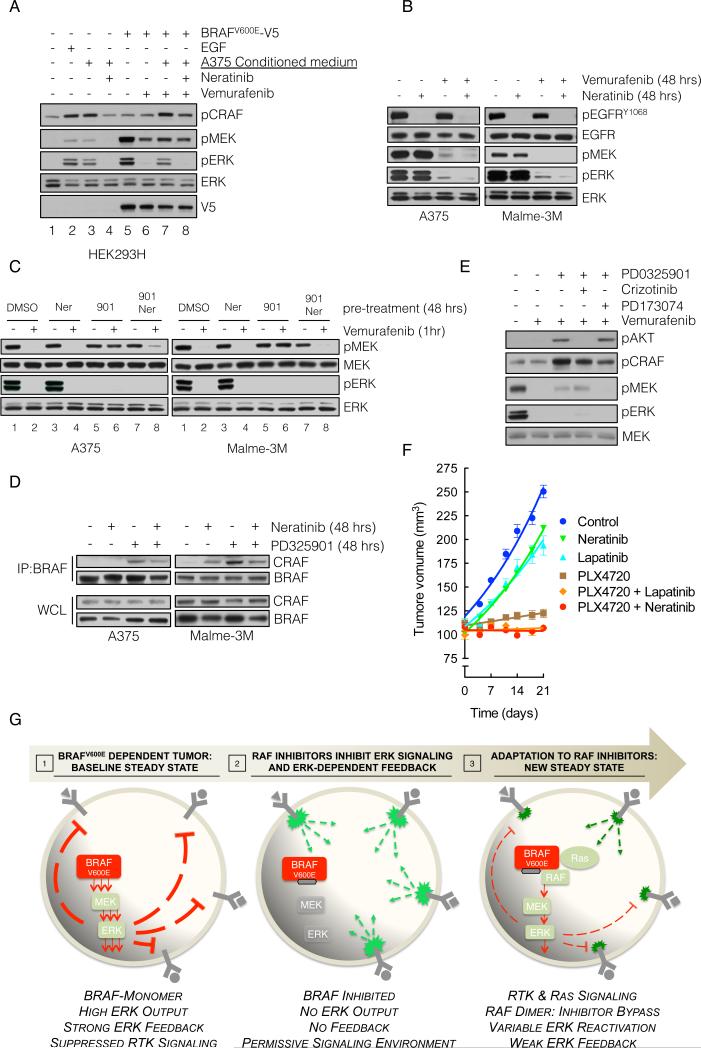

In vivo, BRAFV600E melanomas may be exposed to autocrine, paracrine and endocrine RTK ligands. Our model suggests that reactivation of signalability when ERK feedback is inhibited will enable signaling from mitogenic growth factors. Since ERK rebound occurred in A375 cells exposed to vemurafenib under serum free conditions (data not shown), we hypothesized that secreted ligands were involved. To test this possibility, we collected conditioned medium from serum-deprived A375 cells and found that it induced ERK signaling in 293H cells, as did EGF stimulation (Figure 6A, lanes 2-3). This induction was blocked by the HER kinase inhibitor neratinib (lane 4), suggesting that A375 cells secrete a HER kinase ligand. Furthermore, whereas vemurafenib effectively inhibited pERK in BRAFV600E-transfected 293H cells (lanes 5-6), its ability to inhibit was reduced by A375-conditioned medium (lane 7). Under these conditions, maximal inhibition by vemurafenib was restored when neratinib was also added (lane 8).

(A) BRAFV600E-expressing A375 cells were grown in serum-free medium for 24 hrs and the medium was collected. This conditioned medium (CM) was added to 293H cells (lanes 1-4) or to 293H cells expressing exogenous V5 tagged BRAFV600E (lanes 5-8). The cells were also treated with the indicated combinations of CM, vemurafenib and neratinib in order to assay the effect on ERK singaling.

(B) A375 and Malme3M cells were treated with vemurafenib (1 μM) alone or in combination with neratinib (1 μM) for 48 hours, and the effect on EGFR and downstream signaling was analyzed.

(C) The cells were pre-treated with MEK inhibitor PD0325901 (901, 50 nM), and HER-kinase inhibitor neratinib (Ner, 1 μM), alone or in combination for 48 hours, followed by vemurafenib (1 μM) for 1 hour. Phospho- and total MEK and ERK are determined by IB.

(D) The indicated cell lines were treated with PD0325901 and/or neratinib. WCL were subjected to IP with a BRAF-specific antibody and IB for CRAF. The level of BRAF and CRAF in the WCL is shown.

(E) A375 cells were treated as in C but PD0325901 was combined with crizotinib, and PD173074 (1 μM each), targeting MET and FGFR, respectively.

(F) SkMel-28-derived xenografts were treated with combinations of PLX4720 (50 mg/kg) neratinib (20 mg/kg) and lapatinib (150 mg/kg). Tumor growth (and SEM) as a function of time is shown.

(G) Graphical representation of BRAFV600E melanomas adapting to RAF inhibitors. High levels of ERK-dependent feedback suppress RTK signaling and maintain mutant BRAF in a monomeric, drug-sensitive state. Inhibition of ERK signaling inactivates feedback, and restores RTK signaling to Ras. The resulting RAF dimers are resistant to RAF inhibitors, leading to bypass of inhibition and reactivation of ERK signaling.

To determine whether activated HER kinases support pERK rebound in BRAFV600E cells, cells were treated for 48 hours with vemurafenib, alone or in combination with neratinib. We found that co-treatment with neratinib decreased ERK reactivation in vemurafenib treated cells but had no detectable effect on pERK in the absence of vemurafenib (Figure 6B). Of note, neratinib inhibited pEGFR without affecting pERK in the absence of vemurafenib treatment. This confirms that while upstream receptor activation may be required for ERK rebound, it is not sufficient. Relief of ERK-dependent upstream feedback is the primary cause of ERK reactivation. The receptor may be activated, but the signal is transduced effectively only when vemurafenib blocks ERK feedback.

In Figure 2, we showed that MEK inhibition relieved feedback inhibition of Ras, induced RAF dimerization and decreased the ability of vemurafenib to inhibit MEK phosphorylation. We asked if inhibition of HER kinase signaling in this setting restored the activity of vemurafenib. A375 and Malme-3M cells were pre-treated with a MEK inhibitor (PD0325901) and/or a HER kinase inhibitor (neratinib) for 48 hours, followed by treatment with vemurafenib for one hour. Pre-treatment with the MEK inhibitor alone attenuated the inhibition of MEK phosphorylation by vemurafenib, (Figure 6C, lane 2 vs 6). Neratinib had no effect on ERK signaling when given alone, but restored the ability of vemurafenib to inhibit its target in cells pretreated with the MEK inhibitor (lane 6 vs 8). This restoration was associated with a decrease in the amount of BRAF-CRAF dimers induced by MEK inhibitor treatment, although dimerization was not completely abolished (Figure 6D). This suggests, that while signals originating from HER kinases attenuate the effect of RAF inhibitors, other RTK-dependent pathways likely contribute as well. Indeed, the attenuation of vemurafenib's effect caused by pretreatment with a MEK inhibitor was also reversed by inhibition of FGFR. The MET inhibitor crizotinib did not affect the ability of vemurafenib to inhibit RAF in this system, but it did inhibit feedback-mediated activation of AKT (Figure 6E). Finally, the inhibition of RAF by vemurafenib in combination with HER kinase inhibitors neratinib or lapatinib caused more growth inhibition in vivo than RAF inhibition alone (Figure 6F). These findings together with those in Figure 3 suggest that maximizing inhibition of ERK output by combining RAF inhibitors with inhibitors of ERK rebound may be required for full therapeutic benefit.

DISCUSSION

Activation of BRAF by mutation occurs in approximately 8% of human cancers including the majority of melanomas (Davies et al., 2002, Badalian-Very et al., 2010; Brose et al., 2002; Nikiforova et al., 2003; Schiffman et al., 2010; Tiacci et al., 2011). Recently, ATP-competitive inhibitors of RAF kinase have been shown to be extremely effective in the treatment of melanomas with mutant BRAF (Chapman et al., 2011). This is thought to occur because these drugs inhibit ERK signaling only in tumors with mutant BRAF, whereas they induce ERK in other tumors and normal cells (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010; Heidorn et al., 2010; Joseph et al., 2010; Poulikakos et al., 2010).

Induction occurs because RAF inhibitors cause transactivation of Ras-dependent RAF dimers (Poulikakos et al., 2010). However, BRAFV600E signals as a functional monomer and RAF inhibitors inhibit ERK signaling in this setting. We now show that Ras activity is extremely low in BRAFV600E melanomas. This finding confirms that BRAFV600E functions in a Ras-independent fashion in these cells. The questions arising now are why Ras activity is low, and whether there a causal relationship that explains why a RAF mutant that signals as a monomer is prevalent in tumor cells with low Ras activity? It is possible that physiologic levels of Ras-GTP are low in the normal precursor cells from which melanomas develop. RAF mutants that require Ras dependent dimerization would have low activity in these cells and there would be a strong selection for a RAF mutant capable of signaling as a monomer. Alternatively, ERK activation induces feedback inhibition of upstream signaling, which may be sufficient to potently suppress Ras activation. Here we have demonstrated the latter to be the case. Inhibition of ERK signaling with either RAF or MEK inhibitors significantly induced Ras activation in these tumors.

This induction is likely multifactorial with contributions from the various components of ERK feedback, such as direct phosphorylation of SOS and EGFR, as well as overexpression of Spry. Here we show that knockdown of Spry in BRAFV600E cells increased Ras and RAF activation, and decreased the sensitivity of the pathway to RAF inhibitors. Spry proteins, however, do not affect the direct inhibition of SOS and CRAF by ERK, and therefore, even though Spry knockdown enables signaling from RTKs to SOS, loss of Spry alone cannot account for the full effect of ERK-dependent feedback.

Because physiologic activation of ERK is self-limited in extent and duration (Courtois-Cox et al., 2006), one may ask how oncoproteins cause sufficient activation of ERK output at all? We believe that activation of ERK output requires selection of oncoproteins that have decreased sensitivity to feedback, or second mutations that inactivate the feedback apparatus. In fact, we have previously shown that whereas ERK transcriptional output is quite elevated in tumors with mutant BRAF or mutant Ras; it is only marginally elevated in tumor cells with mutant EGFR or amplified HER2 (Pratilas et al., 2009). In these tumors, ERK pathway feedback is intact and levels of Ras activation are low. In contrast, the mutant Ras protein is constitutively activated (McCormick, 1993) and it is thus refractory to feedback inhibition of upstream signaling.

We propose that there is a powerful selection for the BRAFV600E mutation because it signals as a Ras-independent monomer that is insensitive to feedback. This results in marked elevation of ERK output, with consequent feedback inhibition of Ras-GTP. In agreement with this idea, inhibition of ERK signaling relieves this feedback, and causes induction of Ras activation. Ras activation is associated with a rebound in ERK phosphorylation and output. This rebound is Ras- and SOS-dependent, and more importantly, is CRAF-dependent. Therefore, while the rebound may be potentiated by the loss of ERK phosphatases following RAF inhibition, these findings are consistent with the idea that rebound requires reactivation of upstream signaling and induction of RAF dimers that are refractory to RAF inhibitors but sensitive to MEK inhibition.

If RAF inhibitors cause the Ras-dependent formation of active RAF dimers that are refractory to RAF inhibition, why do these drugs work at all? The induction of Ras-GTP is variable in different melanoma cell lines. It tends to be modest, however, reaching levels that are still significantly below those found in RTK-driven tumor cells. This results in a concomitant modest increase in ERK phosphorylation and in ERK output. In most melanomas, this reactivation is not sufficient to cause resistance. We believe, however, that it can attenuate the effects of therapy, as we find that combining RAF inhibitor with low dose MEK inhibitor causes greater inhibition of pERK and ERK output than either drug alone, and enhanced antitumor activity in vivo in melanoma xenograft models. Thus, the variability observed in the degree of BRAFV600E melanoma response in patients treated with RAF inhibitors may be due in part to variable relief of feedback. This suggests that combined inhibition could increase the degree or duration of response obtained with RAF inhibition alone.

Others have noted that ERK rebound is greater in BRAFV600E thyroid (J. Fagin, unpublished data) and colon (Corcoran et al., 2012) carcinomas and is associated with resistance to the RAF inhibitor. Recent studies show that rebound in colorectal tumors may be associated with feedback reactivation of EGFR function (Corcoran et al., 2012; Prahallad et al., 2012). This may explain why RAF inhibitors have been much less effective in the treatment of BRAFV600E colorectal cancer than they are in melanoma.

Prahallad et al. report that RAF inhibitors induce EGFR activation by inhibiting the ERK-dependent CDC25C phosphatase and thus activating EGFR signaling in colorectal cancer cells (Prahallad et al., 2012). Our data suggest that ERK dependent feedback is complex and that relief of feedback and rebound in ERK activity is due to multiple mechanisms. In melanomas, we did not observe an association between ERK rebound and sustained induction of EGFR phosphorylation. Corcoran et al. also demonstrated that ERK phosphorylation rapidly rebounds after initial inhibition by RAF inhibitors in colorectal cancer (Corcoran et al., 2012). They also find that this rebound is EGFR dependent and associated with Ras activation, but not with induction of EGFR phosphorylation. Here, we demonstrate that relief of ERK dependent feedback by RAF inhibitors results in Ras activation, induction of CRAF-containing dimers, and RAF inhibitor-resistant ERK rebound. In contrast to our findings, Corcoran et al. do not observe Ras reactivation or ERK rebound in melanomas. This is probably because the degree of rebound is greater in colorectal cancer than it is in melanoma, in which it is more difficult to appreciate. We believe that potent ERK-dependent feedback inhibition of signaling is a general phenomenon in tumors with BRAFV600E and that the antitumor effects of drugs that inhibit ERK signaling will be diminished by relief of this feedback.

It is clear that the degree of rebound varies among individual tumors within lineages and that the rebound is greater on the average in some lineages (e.g. colorectal), than in others (e.g. melanoma). Although it is unlikely that this is a simple process dependent on reactivation of a single receptor, it appears that the process may be preferentially dependent on activation of a particular receptor in some lineages (e.g. EGFR in colorectal carcinoma (Corcoran et al., 2012; Prahallad et al., 2012)). Our findings show that signaling from many receptors is suppressed by ERK-dependent feedback in melanomas and reactivated when feedback is relieved by ERK inhibition. It must be kept in mind that as receptor activation of ERK increases, feedback increases and receptor signaling declines. Each tumor reaches a new steady state of ERK activity after RAF inhibition that must be dependent on the level of ERK output required to induce feedback. If feedback mechanisms are sensitive to induction by low levels of ERK output, rebound will be modest. If high levels of ERK output are required to reinitiate feedback, marked ERK rebound will occur and the tumor will be resistant. Future progress will depend on determining the lineage-dependent and tumor specific factors responsible for the new steady state.

Our data show that BRAFV600E melanomas are characterized by high levels of ERK-dependent feedback that operates globally to regulate oncogenic signaling. These cells have markedly decreased sensitivity to extracellular ligands. Indeed, the transduction of signals from activated RTKs, a cellular property that we have termed `signalability’, is markedly suppressed in BRAFV600E melanomas. After ERK inhibition, however, the ERK-dependent negative feedback is lost; and the ability of ligands to activate signaling is markedly enhanced. This is our key finding: at baseline these tumors are relatively insensitive to the effects of secreted growth factors, because the ability of such ligands to induce signaling is disabled. After administration of drugs that effectively inhibit ERK signaling, feedback is reduced and growth factors can signal. Thus, they may attenuate or prevent the antitumor effects of the inhibitor. The signaling network is radically changed and reactivated as an adaptation to inhibition of ERK signaling (Figure 6G).

Recently several reports have shown that ligands, particularly HGF, can cause resistance to RAF inhibitors (Straussman et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2012). Induction of signalability when ERK-dependent feedback is relieved requires the presence of active RTKs. We show here that multiple ligands contribute to ERK rebound in melanomas exposed to RAF inhibitors. However, receptor activation is permissive for induction of signalability, i.e. necessary, but not sufficient. Rebound in ERK signaling is due to relief of feedback inhibition of signal transduction when ERK activation is inhibited.

In order to understand how the tumor adapts to pathway inhibition and design more effective therapies, it will be necessary to identify the pathways that become reactivated in patients, as it is not clear that preclinical models are useful in this regard. This will require comparison of pre-treatment biopsies with biopsies obtained hours after treatment and the development of new technologies to determine which ligands are present and which pathways have become reactivated. This will allow the development of rational combination therapies aimed at inhibiting the adaptation of the tumor to the targeted therapy.

EXPERMIENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell lines, antibodies and reagents

Cell lines were maintained as previously described (Solit et al., 2006). Antibodies against phospho and total ERK, MEK, AKT, CRAF, HER1-3, IGF1R and PDGFRβ were obtained from Cell Signaling; DUSP6, Spry and Ras from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. PD0325901 was synthesized at MSKCC organic synthesis core facility by O. Ouerfelli. Vemurafenib and PLX4720 were provided by Plexxikon. Trametinib and dabrafenib were obtained from GlaxoSmithKline. Neratinib was obtained from Selleckem. Drugs for in vitro studies were dissolved in DMSO to yield 10mM or 1mM stock solutions, and stored at -20°C.

Transfections, Immunoblotting and Ras-GTP assays

siRNA pools were obtained from Dharmacon and transfected into cells by using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX, according to manufacturer's instructions. Cell lysis and immunoblotting were performed as described (Basso et al., 2002). GTP-bound Ras was measured using the CRAF Ras-binding domain (RBD) pull-down and Detection Kit (Thermo Scientific) or an ELISA-based RBD pulldown assay (Millipore), as instructed by the manufacturers.

RT-PCR Analysis

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), reverse-transcribed, and used for quantitative RT-PCR, as previously described (Pratilas et al., 2009). Relative expression of target genes was calculated using the delta–delta Ct method and normalized to the mRNA content of three housekeeping genes.

Animal Studies

Nu/nu athymic mice were obtained from the Harlan Laboratories and maintained in compliance with IACUC guidelines. Subcutaneous xenografts and tumor measurements were performed as described (Solit et al., 2006). All studies were performed in compliance with institutional guidelines under an IACUC approved protocol (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center No. 09-05-009).

Tumor phospho-flow analysis

Tumors excised after 48 hours of drug exposure were homogenized and stained with the Live/Dead Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions, followed by fixation and permeabilization and then analysis by flow cytometry with antibodies detecting: HLA-ABC (eBioscience), pERK1/2 (Cell Signaling), and APC (Southern Biotech).

Secretome screen

A collection of 317 cDNA constructs, representing 220 unique secreted and single pass transmembrane proteins, were reverse-transfected individually into 293T cells using Fugene HD (Promega) in a 384-well plate format (Harbinski et al., 2012). After 4 days of incubation, to allow accumulation of secreted proteins, conditioned media from each well was transferred to the assay cells, to which vemurafenib (1μM) was also added. Proliferation was measured 96 hrs later by using CellTiter-Glo. For each individual experiment (performed in triplicate for each cell line) the RLUs were plotted as a function of the various ligand-expressing constructs. Cell growth in the absence of vemurafenib or conditioned media (i.e. DMSO only), and in the presence of vemurafenib alone, were used as controls. The effect (e.g. rescue) of each ligand in the ability of vemurafenib to inhibit growth was calculated by the formula: (median RLU for the construct - median RLU vemurafenib alone)/median RLU DMSO. The rescue values were then used to create a heat map with the TIBCO Spotfire software. The relative mRNA levels were obtained from expression analysis of the indicated cell lines (Barretina et al., 2012). The relative protein level was determined by immunoblotting (Figure S5D) and densitometric analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been funded by the National Institutes of Health (P01-CA129243, NR; K08-CA127350, CAP), Melanoma Research Alliance (NR, CAP), STARR Cancer Consortium (NR), the Experimental Therapeutics Center of MSKCC (NR), Harry J. Lloyd Charitable Trust (PIP) and Charles A. Dana Foundation (PL). The authors are grateful to Gideon Bollag for providing vemurafenib and PLX4720; to Bart Lutterbach and Giordano Caponigro for insightful discussions; and to Christopher Wilson and Fred Harbinski for their assistance with secretome screen.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Avraham R, Yarden Y. Feedback regulation of EGFR signalling: decision making by early and delayed loops. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2011;12:104–117. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, MacConaill LE, Brandner B, Calicchio ML, Kuo FC, Ligon AH, Stevenson KE, Kehoe SM, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919–1923. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, Wilson CJ, Lehar J, Kryukov GV, Sonkin D, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Basso AD, Solit DB, Chiosis G, Giri B, Tsichlis P, Rosen N. Akt forms an intracellular complex with heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) and Cdc37 and is destabilized by inhibitors of Hsp90 function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39858–39866. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag G, Hirth P, Tsai J, Zhang J, Ibrahim PN, Cho H, Spevak W, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Habets G, et al. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature. 467:596–599. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Brose MS, Volpe P, Feldman M, Kumar M, Rishi I, Gerrero R, Einhorn E, Herlyn M, Minna J, Nicholson A, et al. BRAF and RAS mutations in human lung cancer and melanoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6997–7000. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, Dummer R, Garbe C, Testori A, Maio M, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:2507–2516. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran RB, Ebi H, Turke AB, Coffee EM, Nishino M, Cogdill AP, Brown RD, Pelle PD, Dias-Santagata D, Hung KE, et al. EGFR-mediated reactivation of MAPK signaling contributes to insensitivity of BRAF mutant colorectal cancers to RAF inhibition with vemurafenib. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:227–235. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois-Cox S, Genther Williams SM, Reczek EE, Johnson BW, McGillicuddy LT, Johannessen CM, Hollstein PE, MacCollin M, Cichowski K. A negative feedback signaling network underlies oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:459–472. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty MK, Muller J, Ritt DA, Zhou M, Zhou XZ, Copeland TD, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Lu KP, Morrison DK. Regulation of Raf-1 by direct feedback phosphorylation. Molecular cell. 2005;17:215–224. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Douville E, Downward J. EGF induced SOS phosphorylation in PC12 cells involves P90 RSK-2. Oncogene. 1997;15:373–383. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nature reviews Cancer. 2003;3:11–22. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Eblaghie MC, Lunn JS, Dickinson RJ, Munsterberg AE, Sanz-Ezquerro JJ, Farrell ER, Mathers J, Keyse SM, Storey K, Tickle C. Negative feedback regulation of FGF signaling levels by Pyst1/MKP3 in chick embryos. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1009–1018. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hanafusa H, Torii S, Yasunaga T, Nishida E. Sprouty1 and Sprouty2 provide a control mechanism for the Ras/MAPK signalling pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:850–858. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Harbinski F, Craig VJ, Sanghavi S, Jeffery D, Liu L, Sheppard KA, Wagner S, Stamm C, Buness A, Chatenay-Rivauday C, et al. Rescue screens with secreted proteins reveal compensatory potential of receptor tyrosine kinases in driving cancer growth. Cancer Discov. 2012 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, Brandhuber BJ, Anderson DJ, Alvarado R, Ludlam MJ, Stokoe D, Gloor SL, Vigers G, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431–435. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Heidorn SJ, Milagre C, Whittaker S, Nourry A, Niculescu-Duvas I, Dhomen N, Hussain J, Reis-Filho JS, Springer CJ, Pritchard C, Marais R. Kinase-Dead BRAF and Oncogenic RAS Cooperate to Drive Tumor Progression through CRAF. Cell. 2010;140:209–221. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hingorani SR, Jacobetz MA, Robertson GP, Herlyn M, Tuveson DA. Suppression of BRAF(V599E) in human melanoma abrogates transformation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5198–5202. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph EW, Pratilas CA, Poulikakos PI, Tadi M, Wang W, Taylor BS, Halilovic E, Persaud Y, Xing F, Viale A, et al. The RAF inhibitor PLX4032 inhibits ERK signaling and tumor cell proliferation in a V600E BRAF-selective manner. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:14903–14908. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Bar-Sagi D. Modulation of signalling by Sprouty: a developing story. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2004;5:441–450. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood JM, Bastholt L, Robert C, Sosman J, Larkin J, Hersey P, Middleton M, Cantarini M, Zazulina V, Kemsley K, Dummer R. Phase II, open-label, randomized trial of the MEK1/2 inhibitor selumetinib as monotherapy versus temozolomide in patients with advanced melanoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012;18:555–567. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Leboeuf R, Baumgartner JE, Benezra M, Malaguarnera R, Solit D, Pratilas CA, Rosen N, Knauf JA, Fagin JA. BRAFV600E mutation is associated with preferential sensitivity to mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibition in thyroid cancer cell lines. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;93:2194–2201. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JM, Morrison DJ, Basson MA, Licht JD. Sprouty proteins: multifaceted negative-feedback regulators of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Trends in cell biology. 2006;16:45–54. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick F. Signal transduction. How receptors turn Ras on. Nature. 1993;363:15–16. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarian R, Shi H, Wang Q, Kong X, Koya RC, Lee H, Chen Z, Lee MK, Attar N, Sazegar H, et al. Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature. 2010;468:973–977. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforova MN, Kimura ET, Gandhi M, Biddinger PW, Knauf JA, Basolo F, Zhu Z, Giannini R, Salvatore G, Fusco A, et al. BRAF mutations in thyroid tumors are restricted to papillary carcinomas and anaplastic or poorly differentiated carcinomas arising from papillary carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5399–5404. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Nimnual A, Bar-Sagi D. The two hats of SOS. Science's STKE : signal transduction knowledge environment. 2002;2002:pe36. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Poulikakos PI, Persaud Y, Janakiraman M, Kong X, Ng C, Moriceau G, Shi H, Atefi M, Titz B, Gabay MT, et al. RAF inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly spliced BRAF(V600E). Nature. 2011;480:387–390. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, Shokat KM, Rosen N. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010;464:427–430. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, Di Nicolantonio F, Salazar R, Zecchin D, Beijersbergen RL, Bardelli A, Bernards R. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483:100–103. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pratilas CA, Hanrahan AJ, Halilovic E, Persaud Y, Soh J, Chitale D, Shigematsu H, Yamamoto H, Sawai A, Janakiraman M, et al. Genetic predictors of MEK dependence in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9375–9383. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pratilas CA, Taylor BS, Ye Q, Viale A, Sander C, Solit DB, Rosen N. (V600E)BRAF is associated with disabled feedback inhibition of RAF-MEK signaling and elevated transcriptional output of the pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:4519–4524. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman JD, Hodgson JG, VandenBerg SR, Flaherty P, Polley MY, Yu M, Fisher PG, Rowitch DH, Ford JM, Berger MS, et al. Oncogenic BRAF mutation with CDKN2A inactivation is characteristic of a subset of pediatric malignant astrocytomas. Cancer Res. 2010;70:512–519. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sebolt-Leopold JS, Dudley DT, Herrera R, Van Becelaere K, Wiland A, Gowan RC, Tecle H, Barrett SD, Bridges A, Przybranowski S, et al. Blockade of the MAP kinase pathway suppresses growth of colon tumors in vivo. Nature medicine. 1999;5:810–816. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Solit DB, Garraway LA, Pratilas CA, Sawai A, Getz G, Basso A, Ye Q, Lobo JM, She Y, Osman I, et al. BRAF mutation predicts sensitivity to MEK inhibition. Nature. 2006;439:358–362. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Solit DB, Rosen N. Resistance to BRAF inhibition in melanomas. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:772–774. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, Gonzalez R, Pavlick AC, Weber JS, McArthur GA, Hutson TE, Moschos SJ, Flaherty KT, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:707–714. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K, Barzily-Rokni M, Qian ZR, Du J, Davis A, Mongare MM, Gould J, Frederick DT, et al. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature. 2012;487:500–504. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tiacci E, Trifonov V, Schiavoni G, Holmes A, Kern W, Martelli MP, Pucciarini A, Bigerna B, Pacini R, Wells VA, et al. BRAF mutations in hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2305–2315. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Lee JT, Wang W, Zhang J, Cho H, Mamo S, Bremer R, Gillette S, Kong J, Haass NK, et al. Discovery of a selective inhibitor of oncogenic B-Raf kinase with potent antimelanoma activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3041–3046. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wellbrock C, Karasarides M, Marais R. The RAF proteins take centre stage. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2004a;5:875–885. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wellbrock C, Ogilvie L, Hedley D, Karasarides M, Martin J, Niculescu-Duvaz D, Springer CJ, Marais R. V599EB-RAF is an oncogene in melanocytes. Cancer Res. 2004b;64:2338–2342. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TR, Fridlyand J, Yan Y, Penuel E, Burton L, Chan E, Peng J, Lin E, Wang Y, Sosman J, et al. Widespread potential for growth-factor-driven resistance to anticancer kinase inhibitors. Nature. 2012;487:505–509. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.009

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

http://www.cell.com/article/S1535610812004400/pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.009

Article citations

MEK Inhibitors Lead to PDGFR Pathway Upregulation and Sensitize Tumors to RAF Dimer Inhibitors in NF1-Deficient Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor.

Clin Cancer Res, 30(22):5154-5165, 01 Nov 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39269317 | PMCID: PMC11565172

Complete response to encorafenib plus binimetinib in a <i>BRAF V600E</i>-mutant metastasic malignant glomus tumor.

Oncotarget, 15:717-724, 11 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39392364 | PMCID: PMC11468407

Signaling pathways involved in colorectal cancer: pathogenesis and targeted therapy.

Signal Transduct Target Ther, 9(1):266, 07 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39370455 | PMCID: PMC11456611

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

eIF4F controls ERK MAPK signaling in melanomas with <i>BRAF</i> and <i>NRAS</i> mutations.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 121(44):e2321305121, 22 Oct 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39436655 | PMCID: PMC11536119

Determinants of resistance and response to melanoma therapy.

Nat Cancer, 5(7):964-982, 17 Jul 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39020103

Review

Go to all (363) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

The BRAF(V600E) inhibitor, PLX4032, increases type I collagen synthesis in melanoma cells.

Matrix Biol, 48:66-77, 16 May 2015

Cited by: 18 articles | PMID: 25989506 | PMCID: PMC5048745

RAF inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly spliced BRAF(V600E).

Nature, 480(7377):387-390, 23 Nov 2011

Cited by: 929 articles | PMID: 22113612 | PMCID: PMC3266695

Reactivation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by FGF receptor 3 (FGFR3)/Ras mediates resistance to vemurafenib in human B-RAF V600E mutant melanoma.

J Biol Chem, 287(33):28087-28098, 22 Jun 2012

Cited by: 119 articles | PMID: 22730329 | PMCID: PMC3431627

Langerhans cell histiocytosis: A neoplastic disorder driven by Ras-ERK pathway mutations.

J Am Acad Dermatol, 78(3):579-590.e4, 26 Oct 2017

Cited by: 30 articles | PMID: 29107340

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCI NIH HHS (6)

Grant ID: K08 CA127350

Grant ID: K08-CA127350

Grant ID: P01-CA129243

Grant ID: T32 CA062948

Grant ID: P01 CA129243

Grant ID: P50 CA086438