Abstract

Objectives

Cathepsin L (CTSL) and B (CTSB) have a crucial role in extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation and tissue remodeling, which is a prominent feature of fibrogenesis. The aim of this study was to determine the role and clinical significance of these cathepsins in liver fibrosis.Methods

Hepatic histological CTSL and CTSB expression were assessed in experimental models of liver fibrosis, patients with liver cirrhosis, chronic viral hepatitis, and controls by real-time PCR and immunohistochemistry. Plasma levels of CTSL and CTSB were analyzed in 51 liver cirrhosis patients (Child-Pugh stages A, B and C) and 15 controls.Results

Significantly enhanced CTSL mRNA (P=0.02) and protein (P=0.01) levels were observed in the liver of carbon tetrachloride-treated mice compared with controls. Similarly, hepatic CTSL and CTSB mRNA levels (P=0.02) were markedly increased in Abcb4-/- (ATP-binding cassette transporter knockout) mice compared with wild-type littermates. Elevated levels of CTSL and CTSB were also found in the liver (P=0.001) and plasma (P<0.0001) of patients with hepatic cirrhosis compared with healthy controls. Furthermore, CTSL and CTSB levels correlated well with the hepatic collagen (r=0.5, P=0.007; r=0.64, P=0.0001). CTSL and CTSB levels increased with the Child-Pugh stage of liver cirrhosis and correlated with total bilirubin content (r=0.4/0.2; P≤0.05). CTSL, CTSB, and their combination had a high diagnostic accuracy (area under the curve: 0.91, 0.89 and 0.96, respectively) for distinguishing patients from controls.Conclusions

Our data demonstrate the overexpression of CTSL and CTSB in patients and experimental mouse models, suggesting their potential as diagnostic biomarkers for chronic liver diseases.Free full text

Cathepsin L and B as Potential Markers for Liver Fibrosis: Insights From Patients and Experimental Models

Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Cathepsin L (CTSL) and B (CTSB) have a crucial role in extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation and tissue remodeling, which is a prominent feature of fibrogenesis. The aim of this study was to determine the role and clinical significance of these cathepsins in liver fibrosis.

METHODS:

Hepatic histological CTSL and CTSB expression were assessed in experimental models of liver fibrosis, patients with liver cirrhosis, chronic viral hepatitis, and controls by real-time PCR and immunohistochemistry. Plasma levels of CTSL and CTSB were analyzed in 51 liver cirrhosis patients (Child–Pugh stages A, B and C) and 15 controls.

RESULTS:

Significantly enhanced CTSL mRNA (P=0.02) and protein (P=0.01) levels were observed in the liver of carbon tetrachloride-treated mice compared with controls. Similarly, hepatic CTSL and CTSB mRNA levels (P=0.02) were markedly increased in Abcb4−/− (ATP-binding cassette transporter knockout) mice compared with wild-type littermates. Elevated levels of CTSL and CTSB were also found in the liver (P=0.001) and plasma (P<0.0001) of patients with hepatic cirrhosis compared with healthy controls. Furthermore, CTSL and CTSB levels correlated well with the hepatic collagen (r=0.5, P=0.007; r=0.64, P=0.0001). CTSL and CTSB levels increased with the Child–Pugh stage of liver cirrhosis and correlated with total bilirubin content (r=0.4/0.2; P≤0.05). CTSL, CTSB, and their combination had a high diagnostic accuracy (area under the curve: 0.91, 0.89 and 0.96, respectively) for distinguishing patients from controls.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our data demonstrate the overexpression of CTSL and CTSB in patients and experimental mouse models, suggesting their potential as diagnostic biomarkers for chronic liver diseases.

Introduction

Liver fibrosis can be caused by a variety of etiological factors, including alcohol, viruses, metabolic, and congenital disorders. Chronic liver damage results in the accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins that distorts the hepatic architecture by forming fibrotic scars and regenerative nodules eventually progressing to cirrhosis.1 Liver fibrosis is a dynamic process characterized by abnormal ECM deposition and remodeling. Parenchymal and vascular remodeling in the liver is mediated by proteases secreted by hepatocytes, stellate cells, and endothelial cells.2, 3 Matrix metalloproteinases and cysteine cathepsins can proteolytically degrade components of the ECM and therefore have a critical role in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis.3, 4 Lysosomal cysteine cathepsins are involved in the turnover and breakdown of intracellular proteins, ECM degradation, and tissue remodeling.5 In particular, cathepsin L (CTSL) and cathepsin B (CTSB) have been implicated in various ECM-related disorders, such as dilated cardiomyopathy, lung fibrosis, proteinuric renal disorders, cancer, and osteoporosis.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Interestingly, CTSB has been shown to have an important role in various models of liver injury, including tumour necrosis factor-α-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis,11 free fatty acid–induced liver damage,12 hepatic ischemia–reperfusion injury,13 and cholestasis.14 Similarly, CTSL-deficient mice develop age-dependent myocardial fibrosis and hypertrophy.10 Despite these observations, the role of CTSL and CTSB in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis remains unclear.

Thus, our aim was to examine the expression and clinical relevance of CTSL and CTSB in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. In this study, we investigated the role of CTSL and CTSB in experimental models, including carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis and Abcb4−/− knockout mice. Mice deficient in multidrug resistance Abcb4 gene spontaneously develops fibro-obliterative sclerosing cholangitis and biliary fibrosis caused by the release of toxic bile acids into portal tracts.15 We also assessed the diagnostic and clinical significance of plasma and hepatic CTSL and CTSB levels in patients with different stages of liver cirrhosis.

Methods

CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice

All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (641/IAEC/11) and procedures were followed according to the Indian National Science Academy guidelines for the use and care of experimental animals. Male Swiss albino mice (30–50 g, 8–10-week old) obtained from the Central Animal Facility of All India Institute of Medical Sciences were randomized into two groups each consisting of 6 animals. One group was intraperitoneally injected with a 1:4 (v/v) mixture of CCl4 (1

g, 8–10-week old) obtained from the Central Animal Facility of All India Institute of Medical Sciences were randomized into two groups each consisting of 6 animals. One group was intraperitoneally injected with a 1:4 (v/v) mixture of CCl4 (1 ml/Kg, body weight, M.P. Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and olive oil twice a week over a period of 10 weeks. Another group received an equal volume of olive oil alone. Animals were killed under an overdose of anesthesia (pentobarbitone sodium 100

ml/Kg, body weight, M.P. Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and olive oil twice a week over a period of 10 weeks. Another group received an equal volume of olive oil alone. Animals were killed under an overdose of anesthesia (pentobarbitone sodium 100 mg/kg, intravenous) 2 days after the administration of last dose. A portion of liver from each animal was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histological and immunohistochemical analysis. The remaining liver was immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for the extraction of total RNA.

mg/kg, intravenous) 2 days after the administration of last dose. A portion of liver from each animal was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histological and immunohistochemical analysis. The remaining liver was immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for the extraction of total RNA.

Abcb4−/− mice

The study was performed with permission of the State of Hesse, Regierungspräsidium Giessen, according to section 8 of the German Law for the Protection of Animals. Characterization of Abcb4−/− genotype, hepatic fibrosis phenotype and routine analysis has been described elsewhere.15 Hepatic fibrosis in Abcb4−/− mice was analyzed quantitatively by assessment of hydroxyproline as described earlier.16 Liver samples from 4 (wild type=7, Abcb4−/−=7); 8 (wild type=9, Abcb4−/−=8) and 16 (wild type =10, Abcb4−/−=9) week old mice were analyzed for the CTSL and CTSB mRNA expression by real-time PCR.

Patients and clinico–pathological data collection

The Institutional Human Ethics Committee approved this study before its commencement (IESC/T-341/2.09.2011).

Human liver biopsy specimens

The present study included a total of 51 paraffin-embedded archival liver tissues, which were retrieved from the Department of Pathology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi, India. Samples were examined for fibrosis after Sirius red staining by a panel of pathologists and were graded on a scale of 0 (none) to 6 (cirrhosis) as per the modified Ishak fibrosis staging system.17 There were 28 specimens with liver cirrhosis due to varied pathologies, including non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (n=6), extrahepatic biliary atresia (n=9), chronic hepatitis (n=4), autoimmune hepatitis (n=5), and chronic alcohol abuse (n=4). Ten needle liver biopsies from chronic hepatitis B or C virus-infected patients (CVH) with no or minimal liver fibrosis were also included. Thirteen histologically normal liver biopsies with maintained liver functions served as control in the present study. The clinical details of the patients along with corresponding pathological data are summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

Plasma samples

Fifty-one patients with confirmed diagnosis of liver cirrhosis who visited Gastroenterology OPD of All India Institute of Medical Sciences between 2011 and 2013 were enrolled in the study after their informed consent. Diagnosis of liver cirrhosis in these patients was based on parameters including stigmata of chronic liver disease, ascites, history of gastrointestinal bleeding, overt/subclinical encephalopathy, and coagulopathy. Furthermore, biochemical/hematological investigations such as hemoglobin, platelet count, transaminase ratio, bilirubin, albumin, and prothrombin time were also taken into consideration. Ultrasound examination of the abdomen was performed to look for features of the chronic liver disease in the form of the shrunken liver with altered echotexture, portal hypertension with portal vein size of >12 mm along with collaterals, increase in splenic size, and presence of ascites. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed to look for esophageal varices and gastropathy, a feature of portal hypertension. Child–Pugh–Turcott score was calculated based on serum bilirubin level, serum albumin, ascites, prothrombin time, and grade of encephalopathy to assess the severity of the disease. However, liver biopsy could not be performed in most of the cases owing to ethical issues or contraindication in the form of impaired coagulation parameters and ascites. To ascertain etiology of cirrhosis, serology for hepatitis B and C virus infection, autoimmune markers, serum ceruloplasmin, copper, and iron were performed. History of alcohol intake was taken and blood sugar levels, lipid profile, and thyroid function test was carried out to diagnose NASH or alcoholic steatohepatitis as the possible etiology. Other known serum biomarkers used in the clinic such as aspartate aminotransferase/platelet ratio index (APRI) and fibrosis index (FIB-4) were also calculated for controls and patients as described previously.18, 19 All the patients were treated as per their need. For instance, those having ascites were put on diuretics and salt restrictions and those having features of portal hypertension were put on beta-blockers prophylaxis or on combination of endoscopic variceal ligation and endoscopic scelerotherapy schedule. All were advised to abstain from alcohol consumption. Patients with viral etiology were treated with antivirals if indicated and those having NASH were put on antioxidants. Several clinical and biochemical parameters that were obtained for 51 patients has been summarized in Table 1. Plasma samples from 15 healthy controls with no previous history of any liver damage served as controls in the study. Plasma was obtained from heparinized blood by centrifugation at 3,000

mm along with collaterals, increase in splenic size, and presence of ascites. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed to look for esophageal varices and gastropathy, a feature of portal hypertension. Child–Pugh–Turcott score was calculated based on serum bilirubin level, serum albumin, ascites, prothrombin time, and grade of encephalopathy to assess the severity of the disease. However, liver biopsy could not be performed in most of the cases owing to ethical issues or contraindication in the form of impaired coagulation parameters and ascites. To ascertain etiology of cirrhosis, serology for hepatitis B and C virus infection, autoimmune markers, serum ceruloplasmin, copper, and iron were performed. History of alcohol intake was taken and blood sugar levels, lipid profile, and thyroid function test was carried out to diagnose NASH or alcoholic steatohepatitis as the possible etiology. Other known serum biomarkers used in the clinic such as aspartate aminotransferase/platelet ratio index (APRI) and fibrosis index (FIB-4) were also calculated for controls and patients as described previously.18, 19 All the patients were treated as per their need. For instance, those having ascites were put on diuretics and salt restrictions and those having features of portal hypertension were put on beta-blockers prophylaxis or on combination of endoscopic variceal ligation and endoscopic scelerotherapy schedule. All were advised to abstain from alcohol consumption. Patients with viral etiology were treated with antivirals if indicated and those having NASH were put on antioxidants. Several clinical and biochemical parameters that were obtained for 51 patients has been summarized in Table 1. Plasma samples from 15 healthy controls with no previous history of any liver damage served as controls in the study. Plasma was obtained from heparinized blood by centrifugation at 3,000 g for 10

g for 10 min within 2

min within 2 h of collection.

h of collection.

Table 1

| Clinical parameter | Median (range) |

|---|---|

| Age | 36.0 (28–50) |

| Gender, male/female | 43/8 |

| Child–Pugh stage A/B/C | 20/26/5 |

| Etiology | |

HBV HBV | 22 (43%) |

HCV HCV | 4 (8%) |

Alcohol Alcohol | 14 (28%) |

Cryotogenic Cryotogenic | 8 (16%) |

NASH NASH | 2 (4%) |

HBV+alcohol HBV+alcohol | 1 (1%) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 12.3 (6.5–15.6) |

| Platelet count | 110 (34–377) |

| Prothrombin time | 3 (1–10) |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dl | 1.1 (0.4–4.1) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/l | 46.5 (20–182) |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/l | 40 (16–113) |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/l | 318 (25–672) |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 4 (2.5–5.1) |

| Serum total protein, g/dl | 7.4 (4.5–8.7) |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dl | 23 (12–59) |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) |

| White blood count (× 103 cells/ml) | 5.6 (2.1–13.8) |

| Neutrophil count (cells/ml) | 65 (49–85) |

HBV, Hepatitis B virus; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Liver histology

Liver tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin blocks, and sliced into 5-μm-thick sections. The deparaffinized sections were then stained with hematoxylin–eosin or 0.1% Sirius red–picric acid solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) followed by examination under the light microscope (Olympus BX51 Microscope, Olympus, Melville, NY). All the sections were analyzed and scored for the fibrosis by two expert pathologists, who were blinded about the study.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total cellular RNA from mice liver tissues was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and cDNA was synthesized using RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR reaction contained 200 ng of cDNA sample, SYBR green/ROX Mastermix (Thermo Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania), and set of primers (IDT Technologies, Delhi, India) specific for mouse CTSL20 and CTSB21 (see Supplementary Table S2). PCR conditions comprising 40 cycles of denaturation at 94

ng of cDNA sample, SYBR green/ROX Mastermix (Thermo Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania), and set of primers (IDT Technologies, Delhi, India) specific for mouse CTSL20 and CTSB21 (see Supplementary Table S2). PCR conditions comprising 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30

°C for 30 s, annealing at 56

s, annealing at 56 °C for 30

°C for 30 s, and extension at 72

s, and extension at 72 °C for 30

°C for 30 s were performed in ABI Prism 7500 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, CA). Fold change over controls were calculated using the ΔΔCt method and transcripts were normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA.

s were performed in ABI Prism 7500 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, CA). Fold change over controls were calculated using the ΔΔCt method and transcripts were normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded 5-μm-thick liver sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a gradient of alcohol to water. Thereafter, antigen retrieval was carried out by boiling the slides in prewarm citrate buffer (0.01 mol/l; pH=6) in a microwave oven at 800

mol/l; pH=6) in a microwave oven at 800 W for 12

W for 12 min and 480

min and 480 W for 5

W for 5 min. Sections were incubated with hydrogen peroxide (0.3% v/v) for 30

min. Sections were incubated with hydrogen peroxide (0.3% v/v) for 30 min and then blocked with 5% serum solution for 1

min and then blocked with 5% serum solution for 1 h. Slides were then incubated overnight with goat polyclonal anti-CTSL (1:400; Sc6500; Santa Cruz, TX) or rabbit polyclonal anti-CTSB (1:400; ab58802; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) primary antibody at 4

h. Slides were then incubated overnight with goat polyclonal anti-CTSL (1:400; Sc6500; Santa Cruz, TX) or rabbit polyclonal anti-CTSB (1:400; ab58802; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) primary antibody at 4 °C. Primary antibody was replaced with the isotype-specific non-immune mouse IgG in the negative controls. Slides were washed thrice with tris-buffered saline (TBS, 0.1

°C. Primary antibody was replaced with the isotype-specific non-immune mouse IgG in the negative controls. Slides were washed thrice with tris-buffered saline (TBS, 0.1 M, pH, 7.4) and then incubated with the biotinylated secondary antibody for 1

M, pH, 7.4) and then incubated with the biotinylated secondary antibody for 1 h. Slides were incubated with ABC complex (VECTASTAIN, Burlingame, CA) for 30

h. Slides were incubated with ABC complex (VECTASTAIN, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min at room temperature and visualized using 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine (Dako CYTOMATION, Glostrup, Denmark). Slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin, mounted with DPX, and examined under the light microscope (Olympus BX51 microscope, Olympus, Melville, NY).

min at room temperature and visualized using 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine (Dako CYTOMATION, Glostrup, Denmark). Slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin, mounted with DPX, and examined under the light microscope (Olympus BX51 microscope, Olympus, Melville, NY).

Scoring was carried out by two pathologists independently who were blinded about the diagnosis. A semiquantitative score (H-score) was calculated by the multiplication of staining intensity and distribution grades in bile ducts, fibrotic areas, hepatocytes, and non-parenchymal cells (stellate/kupffer cells). The intensity grades used were: 0 (no staining); 1 (weak); 2 (moderate); or 3 (strong). Grade 3 intensity was equal to the standardized positive control intensity. Distribution grades used for staining were: 0–10%=0; >10–20%=1; >20–40%=2; >40–60%=3; >60–80%=4; and >80–100%=5. A total score was obtained by adding H-scores of each of these compartments.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Plasma levels of CTSL and CTSB were measured using the ELISA Kit (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA and Bosterbio, Pleasanton, CA, respectively) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. In all, 100 μl of undiluted and 1:100 diluted plasma samples were added to the designated wells of CTSL and CTSB ELISA plate, respectively. Standard curves were generated and used to extrapolate the concentrations of these proteases using the GraphPad Prism 7.1 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

μl of undiluted and 1:100 diluted plasma samples were added to the designated wells of CTSL and CTSB ELISA plate, respectively. Standard curves were generated and used to extrapolate the concentrations of these proteases using the GraphPad Prism 7.1 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Quantification of hepatic collagen

Total hepatic collagen was assessed in liver tissues of cirrhotic and CVH patients by computer-assisted image analysis using the Image-Pro plus software 6.1 (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD). The Sirius red–stained slides were photographed sequentially under × 10 magnification, and pictures were then tiled using the Irfan View software (Version 4.40, Irfan Skiljan, Wiener Neustadt, Austria). Digitally stitched images were created to represent whole liver sections as on glass slides. Then, by using the calibrated image analysis software, the total fibrosis was quantified in the entire area (μm2) using segmentation technique.

Data analysis

Groups were compared using Mann–Whitney U-test or Kruskal–Wallis test as appropriate. Correlation analysis was performed by Spearman’s rank-order correlation. The diagnostic performance of plasma CTSL, CTSB, and their combination was evaluated by receiver–operator characteristic (ROC) analysis. The optimal cutoff values were determined by maximizing the sum of sensitivity and specificity; corresponding positive predictive values and negative predictive values were calculated for these cutoff values. To test the diagnostic ability of the combination of plasma CTSL and CTSB, predictive probability values estimated by binary logistic regression with individual variables was used to construct ROC curves. Results have been expressed as mean±s.e.m. unless otherwise specified. All data were analyzed by the GraphPad Prism 7.1 statistical software (GraphPad Software) and STATA 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). *P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Increased expression of CTSL and CTSB in experimental models of liver fibrosis

To determine the role of CTSL and CTSB in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis, we analyzed the expression of these proteases in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. Increased collagen accumulation and porto-portal bridging fibrosis (Ishak score 4–6) were observed in the liver of CCl4-challenged mice compared with that of the controls (see Supplementary Figure S1a,b). The hepatic CTSL mRNA levels were 3.8-fold higher (P=0.02) in CCl4-treated mice compared with vehicle-treated controls (Figure 1a). Similarly, a noticeable increase in CTSB mRNA was also observed in CCl4-treated mice (Figure 1a).

Upregulation of hepatic cathepsin L (CTSL) and cathepsin B (CTSB) expression in experimental liver fibrosis. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) or vehicle (olive oil) twice a week for 10 weeks. Hepatic CTSL and CTSB levels were evaluated by real-time PCR and immunohistochemistry. (a) Relative CTSL mRNA expression was significantly increased in the liver of CCl4-treated mice while CTSB levels were comparable. (b, c) Representative pictures of CTSL and CTSB immunostaining in control and CCl4-treated livers. Liver section from control exhibits granular CTSL immunostaining pattern while in CCl4-treated mice diffuse and strong cytoplasmic staining is evident in the hepatocytes, bile duct epithelium, fibroblasts, and Kupffer cells as indicated by arrows (Original magnification, × 200). (d) Quantification of immunostained CTSL and CTSB revealed overexpression of CTSL in the liver of CCl4-treated mice (values are mean±s.e.m., n=6), *P≤0.05 compared with controls. (e, f) Temporal expression of hepatic CTSL and CTSB transcript levels were quantified in Abcb4−/− mice and their wild-type littermates. Compared with wild-type controls, CTSL and CTSB expression were significantly higher in Abcb4−/− at 4 weeks but gradually decreased to the basal levels by 16 weeks (mean±s.e.m., n=at least 7 mice in each group). *P≤0.05 compared with wild-type controls.

The expression and localization of CTSL and CTSB in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis were further assessed by immunohistochemistry. In controls, mild and discrete CTSL immunostaining was observed mainly in the hepatic stellate/Kupffer cells and some of the hepatocytes (arrows, Figure 1b), while CCl4-treated mice exhibited diffuse and intense cytoplasmic staining for CTSL predominantly in the hepatocytes, stellate/Kupffer cells, infiltrating macrophages, and fibroblasts (Figure 1b). CTSB expression was noted mostly in the non-parenchymal cells of the control liver and was similar to CCl4-treated mice liver (Figure 1c). No immunostaining was observed in the tissue sections that were used as negative controls for both CTSL and CTSB (see Supplementary Figure S1c). Immunoreactivity H-score of hepatic CTSL was significantly (P=0.01) higher in CCl4-treated mice (23±1.7) than that in the controls (15±1.4) (Figure 1d). However, no significant change in CTSB expression was observed after the CCl4 treatment (Figure 1d). These results suggest specific upregulation of CTSL expression in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis.

We also analyzed the expression of these proteases in Abcb4−/− mice model of liver fibrosis. Progressive periductular fibrosis was observed in the Sirius red–stained liver tissues of Abcb4−/− mice as compared with their wild-type controls (see Supplementary Figure S1d). Levels of CTSL and CTSB mRNA were significantly upregulated in 4-week-old Abcb4−/− mice compared with their age-matched wild-type littermates (P=0.02; Figure 1e). Although, 8-week-old Abcb4−/− mice exhibited relatively higher CTSL and CTSB mRNA expression compared with wild-type-BALB/c mice, the difference was not statistically significant. However, at 16 weeks the mRNA levels of these proteases were comparable between the two groups (Figure 1e).

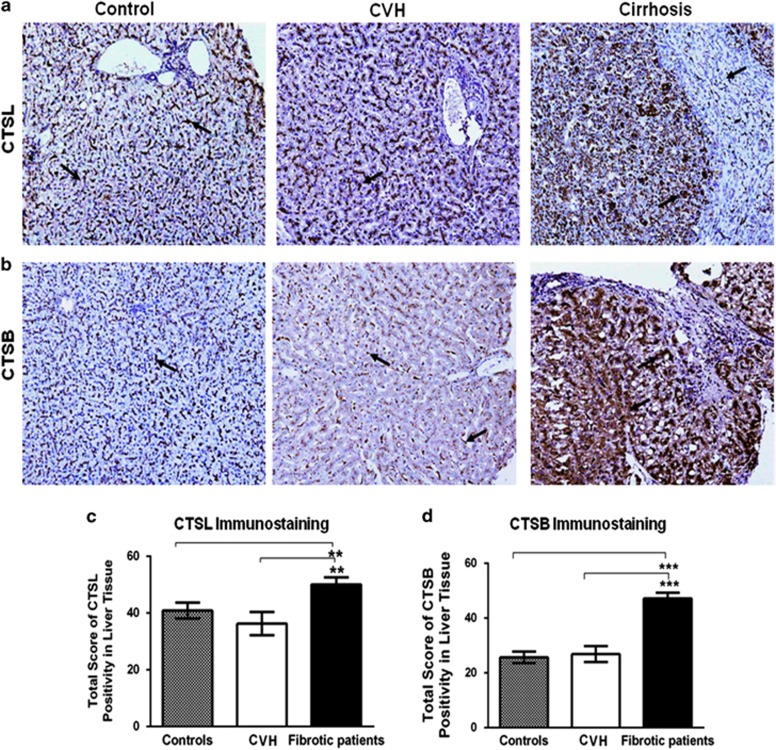

Overexpression of CTSL and CTSB in cirrhotic liver tissues

Having demonstrated the differential regulation of CTSL and CTSB in the experimental models of liver injury, we next sought to determine the expression of these proteases in biopsies from patients having liver cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis with histologically evident mild/no fibrosis, and controls. Liver sections from cirrhotic patients revealed typical perisinusoidal, porto-portal, and porto-central fibrosis (see Supplementary Figure S2a). Immunostaining for CTSL and CTSB was observed in hepatocyte, stellate/Kupffer cells, ductal cells, and septal fibroblasts, though the cellular expression levels were markedly distinct in all the three groups (Figure 2a). In the controls and CVH group, punctate cytoplasmic CTSL and CTSB immunoreactivity was noted in all the liver cells as described above. In patients with liver cirrhosis, the distribution and stain intensities of these proteases were markedly increased in the cytoplasm of ductal cells, macrophages, fibroblasts, and hepatocytes (indicated by arrows in Figure 2a).

Elevation in hepatic cathepsin L (CTSL) and cathepsin B (CTSB) expression in patients with liver cirrhosis. (a, b) Immunohistochemical localization of CTSL and CTSB in the human liver biopsies. In control liver tissue (n=13), punctuate pericanalicular cytoplasmic CTSL and CTSB expression was observed in hepatocytes (arrow), along with mild focal positivity in bile duct epithelial cells, and kupffer cells. Similar to controls, mild CTSL and CTSB immunoreactivity is seen in patients with chronic hepatitis (CVH, n=10). Whereas strong and diffuse immunostaining for both these proteases was evident in hepatocytes, ductal cells, infiltrating histiocytes, and fibrotic septae (indicated by arrows) in the liver of cirrhotic subjects (n=28) (Original magnification, × 200). (c, d) Total immunoscores of (c) CTSL and (d) CTSB were significantly higher in patients with liver cirrhosis compared with controls and CVH patients (mean±s.e.m., **P≤0.001 and ***P≤0.0001, scores of fibrotic patients vs. the corresponding non-fibrotic controls, Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to compare the means of all the groups).

The statistical analysis of immunohistochemical H-score revealed significantly higher CTSL expression in patients with liver cirrhosis (mean=51.3±2.2) as compared with CVH (36.3±4.1) or controls (40.9±2.8) (P=0.002; Figure 2c). Strong CTSL immunostaining above average mean total score of 51.3±2.2 was detected in 15 cases of cirrhosis, out of the 28 cases (54%), and remaining 13 specimens (46%) exhibited moderate immunopositivity. In 82% (19/23) of cirrhotic patients, intense and diffuse CTSB staining was observed in the hepatocytes, ductular epithelial cells, non-parenchymal cells, and septal fibroblasts. Immunoreactivity total scores revealed significantly higher CTSB abundance in cirrhotic patients (47±2.1) than controls (26±2.1) and CVH (27±2.9) (P<0.0001; Figure 2d).

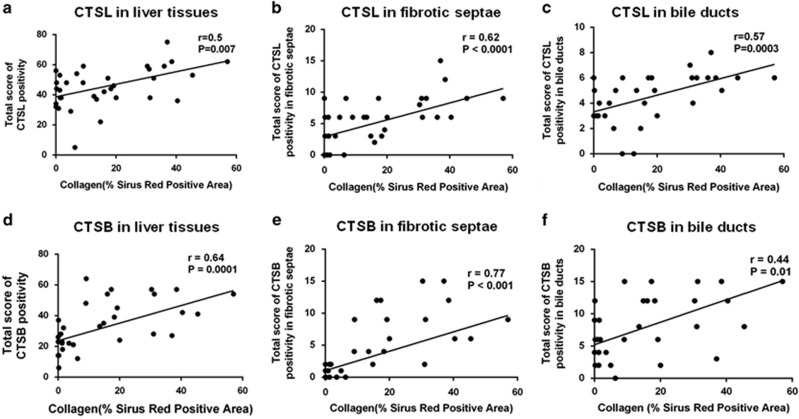

CTSL and CTSB expression increase with the collagen levels in liver tissues

In order to determine whether the expression of collagenolytic CTSL and CTSB modulates the matrix deposition in liver fibrosis, immunohistochemical scores were correlated with morphometrically measured Sirius red–stained fibrotic area in liver tissues from cirrhotic and CVH patient groups. Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed a significant positive association of CTSL and CTSB immunostaining with the extent of hepatic ECM deposition (r=0.5, P=0.007 and r=0.64, P=0.0001, respectively; Figure 3a). Interestingly, CTSL and CTSB expression in fibrotic septa (r=0.62, P<0.0001 and r=0.77, P<0.0001, respectively) and bile duct epithelial cells exhibited a significant positive correlation (r=0.57, P=0.0003 and r=0.44, P=0.01, respectively) with collagen content (Figure 3).

Liver collagen content correlate with hepatic cathepsin L (CTSL) and cathepsin B (CTSB) expression. (a–f) Morphometrically measured Sirius red–stained fibrotic area in the livers of chronic hepatitis and cirrhotic patients exhibited a strong positive correlation with the score of CTSL (a–c) and CTSB (d–f) immunopositivity in whole liver tissue, fibrotic septae, and bile ducts, respectively. Correlation analysis was performed using Spearman-rank test and the individual data points represent samples from individual patients.

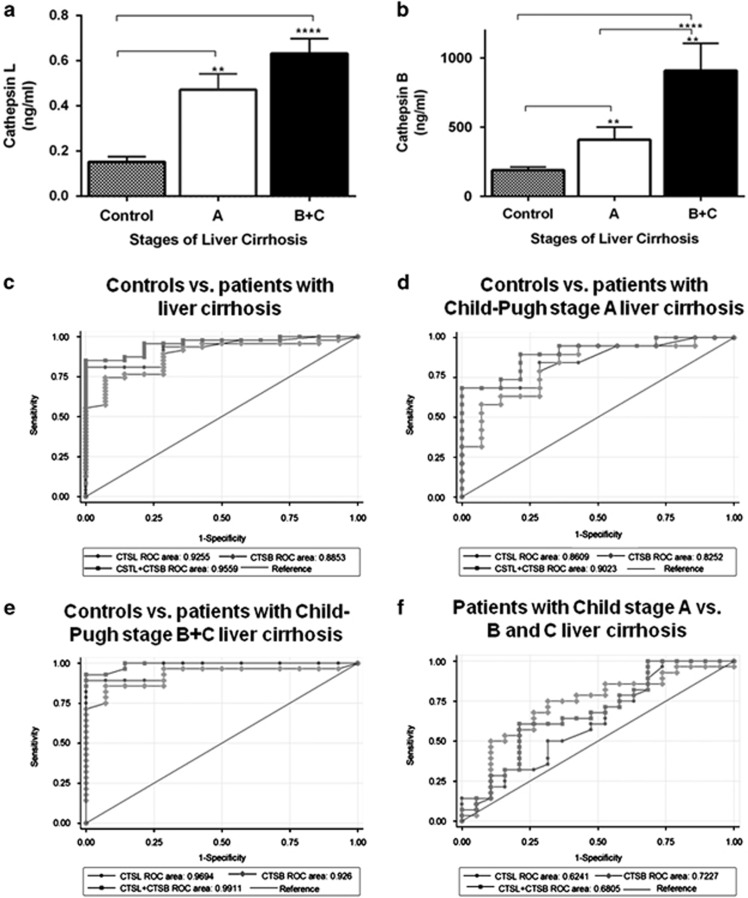

Clinical significance of plasma CTSL and CTSB levels in patients with liver cirrhosis

Because CTSL and CTSB were significantly overexpressed in cirrhotic liver tissues, we measured the plasma levels of these proteases in patients with liver cirrhosis. Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with liver cirrhosis have been summarized in Table 1. Gradual stage-specific increase in the plasma CTSL and CTSB concentration was observed according to the Child–Pugh stages of the liver cirrhosis (Figure 4a). Median plasma concentration of CTSL (0.5 ng/ml, interquartile range (IQR) 0.16–0.63) and CTSB (331.4

ng/ml, interquartile range (IQR) 0.16–0.63) and CTSB (331.4 ng/ml, IQR 227.9–440.8) were significantly higher (P<0.0001) in patients at an early stage (stage A) of liver cirrhosis compared with the controls (CTSL, 0.12

ng/ml, IQR 227.9–440.8) were significantly higher (P<0.0001) in patients at an early stage (stage A) of liver cirrhosis compared with the controls (CTSL, 0.12 ng/ml, IQR 0.09–0.27; CTSB, 141

ng/ml, IQR 0.09–0.27; CTSB, 141 ng/ml, IQR 132–276). Similarly, median plasma CTSL (0.55

ng/ml, IQR 132–276). Similarly, median plasma CTSL (0.55 ng/ml, IQR 0.36–0.74) and CTSB (601.9

ng/ml, IQR 0.36–0.74) and CTSB (601.9 ng/ml, IQR 355.2–922.8) levels in patients with severe liver cirrhosis (stage B+C) were significantly elevated (P<0.0001) compared with the controls. Interestingly, CTSB concentration was remarkably higher in the patients with Child–Pugh stage B+C than in stage A liver cirrhosis (P<0.002) (Figure 4b).

ng/ml, IQR 355.2–922.8) levels in patients with severe liver cirrhosis (stage B+C) were significantly elevated (P<0.0001) compared with the controls. Interestingly, CTSB concentration was remarkably higher in the patients with Child–Pugh stage B+C than in stage A liver cirrhosis (P<0.002) (Figure 4b).

Plasma levels of cathepsin L (CTSL) and cathepsin B (CTSB) increase with Child–Pugh stage of liver cirrhosis. (a, b) Comparison of plasma (a) CTSL and (b) CTSB levels in normal controls (n=15) and patients with liver cirrhosis (Child–Pugh stage A, n=20 and B+C, n=31). Plasma levels of CTSL and CTSB were significantly higher in patients with liver cirrhosis compared with healthy controls. CTSB levels were significantly increased in subjects with Child–Pugh stages B and C compared with patients with Child–Pugh class A liver cirrhosis (values are mean±s.e.m., *P≤0.05, **P≤0.001 and ***P≤0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to compare the means of all the groups). (c–f) The diagnostic accuracy of plasma CTSL, CTSB, and their combination in chronic liver disease with cirrhosis. Receiver–operating characteristic (ROC) curves was performed to determine the area under the curve (AUC) using plasma CTSL, CTSB, or their combination to predict hepatic cirrhosis (c) control vs. patients with liver cirrhosis (Child–Pugh stage A+B+C); (d) control vs. patients with Child class A liver cirrhosis; (e) control vs. patients with Child class B+C liver cirrhosis; (f) patients with Child class A vs. B+C liver cirrhosis.

Association of plasma CTSL and CTSB levels with patient characteristics are given in Table 2. Among various clinicopathological parameters, CTSL (ρ=0.52, P<0.01) and CTSB (ρ=0.68, P<0.01) levels exhibited positive correlation with the severity of the fibrosis (Child–Pugh stage). Similarly, a direct correlation between plasma CTSL levels and neutrophil count (ρ=0.47, P=0.01) as well as total bilirubin concentrations (ρ=0.38, P=0.04) was also observed. However, plasma CTSB levels displayed a strong association with total bilirubin content (ρ=0.23, P=0.05) and inverse correlation with the albumin levels (ρ=−0.28, P=0.04) (Table 2). Interestingly, a strong correlation was observed between plasma CTSL and CTSB levels (ρ=0.34, P=0.02).

Table 2

| Parameters | CTSL | CTSB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ρ | P | N | ρ | P | |

| Age | 51 | 0.13 | NS | 51 | 0.05 | NS |

| Hemoglobin | 51 | −0.08 | NS | 48 | 0.05 | NS |

| White blood count (cells/ml) | 51 | −0.03 | NS | 50 | −0.08 | NS |

| Neutrophil count | 49 | 0.47** | 0.01 | 45 | 0.19 | NS |

| Prothrombin time | 49 | −0.04 | NS | 45 | 0.23 | NS |

| Platelet count | 51 | −0.08 | NS | 50 | 0.07 | NS |

| Sodium | 51 | −0.03 | NS | 50 | −0.20 | NS |

| Potassium | 51 | −0.09 | NS | 50 | 0.06 | NS |

| Urea | 51 | 0.23 | NS | 49 | −0.01 | NS |

| Creatinine | 51 | 0.16 | NS | 51 | −0.03 | NS |

| Total bilirubin | 51 | 0.38** | 0.04 | 50 | 0.23* | 0.05 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 51 | 0.25 | NS | 50 | 0.21 | NS |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 51 | 0.19 | NS | 51 | −0.06 | NS |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 51 | 0.08 | NS | 51 | 0.04 | NS |

| Serum total protein | 51 | 0.15 | NS | 51 | 0.12 | NS |

| Serum albumin | 51 | −0.16 | NS | 51 | −0.28* | 0.04 |

| Child–Pugh stage | 65 | 0.52** | <0.01 | 65 | 0.68** | <0.01 |

| CTSL | — | — | — | 47 | 0.34* | 0.02 |

| CTSB | 47 | 0.34* | 0.02 | — | — | — |

CTSB, cathepsin B; CTSL, cathepsin L; NS, not significant.

Correlations of plasma CTSL and CTSB with other clinical parameters were analyzed by Spearman rank correlation test, and data are presented for all the patients. For correlations of Child–Pugh stage with CTSL and CTSB, control values were also included. *Indicates P value <0.05. **P≤0.01.

We performed ROC curve analysis to examine the diagnostic potential of elevated plasma CTSL and CTSB for the assessment of liver cirrhosis severity (Figure 4c–f) and compared their diagnostic performance with known serum biomarkers, such as FIB-4 and APRI (Table 3). ROC analysis revealed an optimal cutoff value of 0.27 ng/ml (80.4% sensitivity; 78.6% specificity) and 287.4

ng/ml (80.4% sensitivity; 78.6% specificity) and 287.4 ng/ml (76.6% sensitivity; 80% specificity) for plasma CTSL and CTSB, respectively, to distinguish patients with liver cirrhosis from healthy controls (Figure 4c and Table 3). For prediction of liver fibrosis, the area under the curve (AUC) for CTSL (0.91), CTSB (0.89), and their combination (0.96) (Figure 4c) was comparable to the discriminatory power of APRI (0.94) and FIB-4 (0.92). ROC analysis revealed similar observations when subgroups of patients with the increasing Child–Pugh stages were compared with healthy controls (Figure 4d and Table 3). For the advanced stage, the AUC of CTSL (0.97), CTSB (0.93), and their combination (0.99) was better than the diagnostic performance of FIB-4 (0.91) and APRI (0.94) (Table 3). Interestingly, an AUC value of 0.72 for CTSB was obtained for differentiating between patients with early and advance stages of liver cirrhosis, compared with an AUC of 0.62 and 0.68 for CTSL and their combination, respectively (Figure 4f). Furthermore, the AUC of CTSB for predicting early cirrhosis from the advance stage was superior to APRI (0.45) and FIB-4 (0.52) (Table 3). Thus CTSB holds better diagnostic value in differentiating late-stage cirrhotic subjects from those with early-stage liver diseases.

ng/ml (76.6% sensitivity; 80% specificity) for plasma CTSL and CTSB, respectively, to distinguish patients with liver cirrhosis from healthy controls (Figure 4c and Table 3). For prediction of liver fibrosis, the area under the curve (AUC) for CTSL (0.91), CTSB (0.89), and their combination (0.96) (Figure 4c) was comparable to the discriminatory power of APRI (0.94) and FIB-4 (0.92). ROC analysis revealed similar observations when subgroups of patients with the increasing Child–Pugh stages were compared with healthy controls (Figure 4d and Table 3). For the advanced stage, the AUC of CTSL (0.97), CTSB (0.93), and their combination (0.99) was better than the diagnostic performance of FIB-4 (0.91) and APRI (0.94) (Table 3). Interestingly, an AUC value of 0.72 for CTSB was obtained for differentiating between patients with early and advance stages of liver cirrhosis, compared with an AUC of 0.62 and 0.68 for CTSL and their combination, respectively (Figure 4f). Furthermore, the AUC of CTSB for predicting early cirrhosis from the advance stage was superior to APRI (0.45) and FIB-4 (0.52) (Table 3). Thus CTSB holds better diagnostic value in differentiating late-stage cirrhotic subjects from those with early-stage liver diseases.

Table 3

| AUC (95%CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Cutoff (ng/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control vs. patients with liver cirrhosis (Child–Pugh stage A+B+C) | ||||||

CTSL CTSL | 0.91 (0.85–0.98) | 80.4 | 78.6 | 93.2 | 52.3 | >0.27 |

CTSB CTSB | 0.89 (0.81–0.98) | 76.6 | 80 | 93 | 47.8 | >287.4 |

CTSL+CTSB CTSL+CTSB | 0.95 (0.91–1.00) | 87.2 | 85.7 | 95.3 | 66.7 | — |

APRI APRI | 0.94 (0.89–1.00) | 87.1 | 85 | 61.3 | 42.3 | >0.23 |

FIB-4 FIB-4 | 0.92 (0.85–0.99) | 88.2 | 85.7 | 95.7 | 66.7 | >1.07 |

| Control vs. patients with Child class A liver cirrhosis | ||||||

CTSL CTSL | 0.82 (0.68–0.96) | 80.0 | 71.4 | 80 | 71.4 | >0.15 |

CTSB CTSB | 0.83 (0.69–0.97) | 79.0 | 73.3 | 80.2 | 71.6 | >235.74 |

CTSL+CTSB CTSL+CTSB | 0.90 (0.80–1.00) | 78.6 | 78.6 | 83 | 73 | — |

APRI APRI | 0.94 (0.87–1.00) | 85.0 | 92.9 | 94.4 | 81.3 | >0.23 |

FIB-4 FIB-4 | 0.93 (0.84–1.00) | 85.0 | 85.7 | 89.5 | 80.0 | >1.17 |

| Controls vs. patients with Child class B+C liver cirrhosis | ||||||

CTSL CTSL | 0.97 (0.93–1.00) | 90.3 | 85.7 | 93.1 | 85.7 | >0.28 |

CTSB CTSB | 0.93 (0.84–1.00) | 85.7 | 86.7 | 93 | 85.2 | >317.17 |

CTSL+CTSB CTSL+CTSB | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 92.7 | 92.7 | 96.2 | 86.7 | — |

APRI APRI | 0.94 (0.88–1.00) | 87.1 | 92.3 | 96.4 | 76.5 | >0.23 |

FIB-4 FIB-4 | 0.91 (0.83–0.99) | 87.1 | 85.7 | 93.1 | 75.0 | >1.07 |

| Patients with Child class A vs. B+C liver cirrhosis | ||||||

CTSL CTSL | 0.64 (0.48–0.80) | 58.1 | 55.0 | 66.7 | 45.8 | >0.53 |

CTSB CTSB | 0.72 (0.61–0.89) | 73.9 | 73.7 | 82.1 | 65.2 | >430.6 |

CTSL+CTSB CTSL+CTSB | 0.68 (0.52–0.84) | 60.7 | 63.2 | 70.8 | 47.8 | — |

APRI APRI | 0.45 (0.28–0.63) | 61.3 | 45.0 | 63.3 | 42.8 | >0.35 |

FIB-4 FIB-4 | 0.52 (0.35–0.69) | 64.5 | 50.0 | 66.7 | 47.6 | >2.6 |

APRI, aspartate aminotransferase/platelet ratio index; AUC, area under the curve; CTSB, cathepsin B; CTSL, cathepsin L; FIB-4, fibrosis index; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, negative predictive value.

Estimated threshold for CTSL+CTSB is determined by logistic regression analysis.

AUC were calculated using receiver–operating characteristic curves. Cutoff values were determined by maximizing the sum of sensitivity and specificity.

Discussion

The primary objective of the present study was to assess the utility of CTSL and CTSB as blood-based biomarkers for liver fibrosis. Our results demonstrate significant upregulation of CTSL and CTSB expression in different murine models as well as in two independent cohorts of patients with liver fibrosis. We observed elevated levels of CTSL in the CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. Similarly, CTSL and CTSB levels were transiently increased during the active phase of biliary fibrosis in Abcb4−/− mice. Furthermore, the expression of these proteases was also significantly increased in the liver of fibrotic patients and positively correlated with hepatic collagen levels. Finally, we demonstrate progressive increase in plasma CTSL and CTSB concentrations with advancement in the stages of liver cirrhosis thereby suggesting their potential diagnostic utility as non-invasive biomarkers.

Liver biopsy has been used as gold standard for the diagnosis and staging of liver diseases but involves considerable disadvantages, such as sampling error and invasion.19 Hence, continuous efforts are being made to identify novel serological biomarkers for liver cirrhosis. Cysteine cathepsins are very potent class of proteases that degrades various constituents of ECM, including elastin, proteoglycans, laminin, collagen (type I, XVIII, and IV), fibronectins, and other structural components of the liver.10 Lysosomal proteases CTSL and CTSB have been implicated in ECM degradation and tissue remodeling during wound healing,22 atherosclerosis,23 cardiac,6 pulmonary,7 and renal fibrosis.24, 25 These proteases have also been proposed as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for various malignancies.26 Consistent with these reports, we observed significantly higher mRNA and protein levels of hepatic CTSL in CCl4-treated mice when compared with the controls. This finding supports the pro-fibrotic role of this protease in experimental proteinuric kidney diseases10 and diabetic nephropathy.27 CTSB inhibition has been shown to reduce the ECM accumulation and liver damage in ischemia–reperfusion injury13 and bile duct ligation model of liver fibrosis.14 On the contrary, inhibition of CTSB activity did not mitigate CCl4-induced hepatocellular damage in mice.28 We did not observe any significant difference in CTSB levels between CCl4-treated and control mice. Consistent with the findings of Moles et al.,28 our results suggest that involvement of CTSB in liver damage could vary in different experimental models of hepatic fibrosis. Expression of CTSL and CTSB was further validated in Abcb4−/−mice that spontaneously develop liver injury and morphological features resembling primary sclerosing cholangitis. Bile duct injury in Abcb4−/− mice is initiated by the damage of tight junctions and basement membranes followed by leakage of bile to the portal tract resulting in periportal biliary fibrosis.15 In Abcb4−/− mice, we observed a transient increase in the expression of hepatic CTSL and CTSB mRNA at 4 weeks of age that gradually declined and thereafter reached the basal level at 16 weeks. These results suggest that upregulation of these proteases may be an early event in hepatic fibrosis in Abcb4−/− mice. Popov et al.29 also reported peak levels of pro-fibrogenic transcripts at 4 weeks and suggested this period to be the most active phase of progressive liver fibrosis in Abcb4−/− mice. Malignant tumor cell secret significant amount of these lysosomal proteases into the ECM that facilitates invasion and metastasis.30 In view of these reports, it could be argued that CTSL and CTSB secreted by hepatic cells may disrupt the bile duct junctions and basement membrane, resulting in concomitant leakage of toxic bile acids into portal spaces, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of biliary fibrosis in Abcb4−/− mice.

Consistent with our findings in experimental models, we observed significantly higher levels of CTSL and CTSB in the livers of patients with end-stage hepatic cirrhosis as compared with CVH patients and controls. Importantly, our results ruled out the effect of inflammatory activity associated with this pathology on the expression of these proteases as the histological hepatic CTSL and CTSB levels in CHV patients were comparable to that in controls. Similarly, CTSB levels were found to be elevated in the liver of patients with NASH.31 Immunohistochemical analysis of liver biopsies revealed granular (lysosomal) staining pattern for these proteases in controls, whereas diffuse and irregular cytoplasmic staining suggestive of their release from the lysosomal compartments was evident in patients with liver cirrhosis. These results are in good agreement with the previous report that demonstrated redistribution of hepatic CTSB from endosomal compartments to the cytosol in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.12 Murawaki and colleagues also demonstrated elevated CTSL and CTSB activities in autopsied fibrotic livers and reported a positive correlation with hydroxyproline levels.32 Thus our results, in agreement with previous findings, demonstrate a strong association of these proteases with the hepatic collagen accumulation. Interestingly, renal cathepsin L, K, S, and C levels were found to be significantly upregulated in the mice model of chronic kidney disease and their selective inhibition by E64d impaired collagen degradation.24 Moreover, lysosomal destabilization and release of CTSB into cytosol has been shown to induce hepatocyte apoptosis in free fatty acid–mediated lipotoxicity.12, 33 Furthermore, CTSB mediates the activation of stellate cells into ECM-producing fibroblasts, which have a key role in liver fibrosis.28 Thus these proteases may have a significant role in altering the tissue microenvironment, ECM remodeling, hepatocytic death, and activation of myofibroblasts during the progression of liver fibrosis.

To the best of our knowledge, this study for the first time demonstrates a parallel increase in plasma CTSL and CTSB concentrations with the severity (Child–Pugh stages) of liver cirrhosis. As hepatic expression of CTSL and CTSB was studied in archival tissues, we did not have access to plasma of the same patients. Therefore, in the present study, CTSL and CTSB levels were estimated in an independent cohort of plasma samples obtained from patients with different stages of liver cirrhosis and healthy controls. The results of plasma patient cohort used in our study nevertheless reflected the tissue levels of CTSL and CTSB. Leto et al.34 also reported elevated serum CTSB levels in patients with liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Our study is the first clinical investigation that reveals the diagnostic utility of plasma CTSL and CTSB in predicting liver cirrhosis. Based on the ROC analysis, CTSL, CTSB, and their combination emerged as strong diagnostic markers with AUCs 0.91, 0.89, and 0.95, respectively, for assessment of liver fibrosis compared with controls. Furthermore, the performance of these proteases was comparable to that of other non-invasive indirect biomarkers, such as APRI (0.94) and FIB-4 (0.92). However, it is noteworthy that plasma CTSB with AUC (0.72) showed better performance than APRI (0.45) and FIB-4 index (0.52) to differentiate intermediate stages of liver cirrhosis. Thus, plasma levels of CTSL and CTSB reflected the extent of disease severity in patients with liver cirrhosis irrespective of the etiology. Although our results demonstrate the clinical utility of CTSL and CTSB in liver cirrhosis, this pilot study has several limitations. The statistical power of our findings can be improved by performing the study in a large cohort of patients. Furthermore, CTSL and CTSB levels have been validated in an independent cohort of plasma samples that includes patients with different stages of liver cirrhosis as obtaining liver biopsies of each patient was not feasible. Hence, it will be desirable to study the expression of CTSL and CTSB in liver biopsies and plasma of the same individuals.

In summary, our study demonstrates upregulation of CTSL and CTSB expression in chronic liver diseases and suggests their pathogenic link with hepatic fibrosis. In view of their ability to degrade ECM, these proteases may assist in hepatic remodeling and alterations of ECM after injury. Furthermore, plasma CTSL and CTSB were identified as a powerful diagnostic blood-based marker to assess the severity of liver fibrosis. However, large-scale studies are warranted to substantiate the diagnostic performance of these lysosomal proteases as non-invasive biomarkers of liver fibrosis.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology website (http://www.nature.com/ctg)

Guarantor of the article: Shyam S. Chuahan, PhD.

Specific author’s contribution: M. Manchanda: performed all the experiments, collected samples, data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. R.M. Pandey: statistical analysis and data analysis. Elke Roeb and Martin Roderfeld: planning, data analysis, and reviewing the manuscript. Prasenjit Das, Siddhartha Datta Gupta and Gaurav PS Gahlot: examined, reviewed, and scored the immunohistochemistry. Anoop Saraya: planning the study, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation. Shyam S. Chauhan: conceptualized the project, planned experiments, obtained funding for the project, provided infrastructure and resources for the work, analyzed and interpreted the results and corrected and finalized the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft submitted.

Financial support: This study was financially supported by Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India (BT/PR7146/MED/30/900/12). M.M. is a recipient of Senior Research Fellowship (SRF) of Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), India.

Potential competing interests: None.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure Legends

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Table S1

Supplementary Table S2

References

- Pellicoro A, Ramachandran P, Iredale JP et al. Liver fibrosis and repair: immune regulation of wound healing in a solid organ. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14: 181–194. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2011; 6: 425–456. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte S, Baber J, Fujii T et al. Matrix metalloproteinases in liver injury, repair and fibrosis. Matrix Biol 2015; 44-46: 147–156. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Moles A, Tarrats N, Fernandez-Checa JC et al. Cathepsin B overexpression due to acid sphingomyelinase ablation promotes liver fibrosis in Niemann-Pick disease. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 1178–1188. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber A, Wille A, Welte T et al. Interleukin-6 and transforming growth factor-beta 1 control expression of cathepsins B and L in human lung epithelial cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2001; 21: 11–19. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Y, Nair S. Proteases in cardiometabolic diseases: pathophysiology, molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015; 1852: 195–208. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Buhling F, Rocken C, Brasch F et al. Pivotal role of cathepsin K in lung fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2004; 164: 2203–2216. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed MM, Sloane BF. Cysteine cathepsins: multifunctional enzymes in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2006; 6: 764–775. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Saftig P, Hunziker E, Wehmeyer O et al. Impaired osteoclastic bone resorption leads to osteopetrosis in cathepsin-K-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 13453–13458. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser J, Adair B, Reinheckel T. Specialized roles for cysteine cathepsins in health and disease. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 3421–3431. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Guicciardi ME, Deussing J, Miyoshi H et al. Cathepsin B contributes to TNF-alpha-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis by promoting mitochondrial release of cytochrome c. J Clin Invest 2000; 106: 1127–1137. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein AE, Werneburg NW, Canbay A et al. Free fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-alpha expression via a lysosomal pathway. Hepatology 2004; 40: 185–194. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin-Bey ES, Canbay A, Bronk SF et al. Cathepsin B inactivation attenuates hepatocyte apoptosis and liver damage in steatotic livers after cold ischemia-warm reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2005; 288: G396–G402. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Canbay A, Guicciardi ME, Higuchi H et al. Cathepsin B inactivation attenuates hepatic injury and fibrosis during cholestasis. J Clin Invest 2003; 112: 152–159. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Fickert P, Fuchsbichler A, Wagner M et al. Regurgitation of bile acids from leaky bile ducts causes sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2 (Abcb4) knockout mice. Gastroenterology 2004; 127: 261–274. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Roderfeld M, Rath T, Voswinckel R et al. Bone marrow transplantation demonstrates medullar origin of CD34+ fibrocytes and ameliorates hepatic fibrosis in Abcb4−/− mice. Hepatology 2010; 51: 267–276. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol 1995; 22: 696–699. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B et al. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology 2007; 46: 32–36. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wai C-T, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2003; 38: 518–526. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada A, Ishimaru N, Arakaki R et al. Cathepsin L inhibition prevents murine autoimmune diabetes via suppression of CD8(+) T cell activity. PLoS ONE 2010; 5: e12894. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Withana NP, Blum G, Sameni M et al. Cathepsin B inhibition limits bone metastasis in breast cancer. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 1199–1209. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Buth H, Wolters B, Hartwig B et al. HaCaT keratinocytes secrete lysosomal cysteine proteinases during migration. Eur J Cell Biol 2004; 83: 781–795. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Sukhova GK, Zhang J et al. Cathepsin L activity is essential to elastase perfusion–induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011; 31: 2500–2508. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Guisa JM, Cai X, Collins SJ et al. Mannose receptor 2 attenuates renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 236–251. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Fox C, Cocchiaro P, Oakley F et al. Inhibition of lysosomal protease cathepsin D reduces renal fibrosis in murine chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 20101. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Fonovic M, Turk B. Cysteine cathepsins and their potential in clinical therapy and biomarker discovery. Proteomics Clin Appl 2014; 8: 416–426. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Garsen M, Rops AL, Dijkman H et al. Cathepsin L is crucial for the development of early experimental diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 2016; 90: 1012–1022. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Moles A, Tarrats N, Fernandez-Checa JC et al. Cathepsins B and D drive hepatic stellate cell proliferation and promote their fibrogenic potential. Hepatology 2009; 49: 1297–1307. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Popov Y, Patsenker E, Fickert P et al. Mdr2 (Abcb4)−/− mice spontaneously develop severe biliary fibrosis via massive dysregulation of pro- and antifibrogenic genes. J Hepatol 2005; 43: 1045–1054. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan SS, Ray D, Kane SE et al. Involvement of carboxy-terminal amino acids in secretion of human lysosomal protease cathepsin L. Biochemistry 1998; 37: 8584–8594. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Moles A, Tarrats N, Morales A et al. Acidic sphingomyelinase controls hepatic stellate cell activation and in vivo liver fibrogenesis. Am J Pathol 2010; 177: 1214–1224. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Murawaki Y, Kawasaki H. Collagenolytic cathepsin B and L activity in experimental fibrotic liver and human liver. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol 1992; 76: 95–112. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LR, Kurosawa H, Bronk SF et al. Cathepsin B contributes to bile salt-induced apoptosis of rat hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 1997; 113: 1714–1726. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Leto G, Tumminello FM, Pizzolanti G et al. Lysosomal cathepsins B and L and Stefin A blood levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and/or liver cirrhosis: potential clinical implications. Oncology 1997; 54: 79–83. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology are provided here courtesy of American College of Gastroenterology

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1038/ctg.2017.25

Article citations

Hepatic Proteomic Changes Associated with Liver Injury Caused by Alcohol Consumption in <i>Fpr2<sup>-</sup></i><sup>/<i>-</i></sup> Mice.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(18):9807, 11 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39337294 | PMCID: PMC11432144

Precision nutrition to reset virus-induced human metabolic reprogramming and dysregulation (HMRD) in long-COVID.

NPJ Sci Food, 8(1):19, 30 Mar 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38555403 | PMCID: PMC10981760

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Unveiling the Antiviral Efficacy of Forskolin: A Multifaceted In Vitro and In Silico Approach.

Molecules, 29(3):704, 03 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38338448 | PMCID: PMC10856047

Impact of the Recognition Part of Dipeptidyl Nitroalkene Compounds on the Inhibition Mechanism of Cysteine Proteases Cruzain and Cathepsin L.

ACS Catal, 13(9):6289-6300, 24 Apr 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37180968 | PMCID: PMC10167892

Impact of the Warhead of Dipeptidyl Keto Michael Acceptors on the Inhibition Mechanism of Cysteine Protease Cathepsin L.

ACS Catal, 13(20):13354-13368, 03 Oct 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37881790 | PMCID: PMC10594577

Go to all (23) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Cathepsins B and L in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: potential poor prognostic markers.

Ann Hematol, 89(12):1223-1232, 22 Jun 2010

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 20567828

Expression and Clinical Implications of Cysteine Cathepsins in Gallbladder Carcinoma.

Front Oncol, 9:1239, 22 Nov 2019

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 31824841 | PMCID: PMC6883407

Prognostic impact of cysteine proteases cathepsin B and cathepsin L in pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Pancreas, 29(3):204-211, 01 Oct 2004

Cited by: 54 articles | PMID: 15367886

Clinical significance of cathepsin L and cathepsin B in dilated cardiomyopathy.

Mol Cell Biochem, 428(1-2):139-147, 10 Jan 2017

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 28074340