Abstract

Background

Nivolumab plus ipilimumab produced objective responses in patients with advanced renal-cell carcinoma in a pilot study. This phase 3 trial compared nivolumab plus ipilimumab with sunitinib for previously untreated clear-cell advanced renal-cell carcinoma.Methods

We randomly assigned adults in a 1:1 ratio to receive either nivolumab (3 mg per kilogram of body weight) plus ipilimumab (1 mg per kilogram) intravenously every 3 weeks for four doses, followed by nivolumab (3 mg per kilogram) every 2 weeks, or sunitinib (50 mg) orally once daily for 4 weeks (6-week cycle). The coprimary end points were overall survival (alpha level, 0.04), objective response rate (alpha level, 0.001), and progression-free survival (alpha level, 0.009) among patients with intermediate or poor prognostic risk.Results

A total of 1096 patients were assigned to receive nivolumab plus ipilimumab (550 patients) or sunitinib (546 patients); 425 and 422, respectively, had intermediate or poor risk. At a median follow-up of 25.2 months in intermediate- and poor-risk patients, the 18-month overall survival rate was 75% (95% confidence interval [CI], 70 to 78) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 60% (95% CI, 55 to 65) with sunitinib; the median overall survival was not reached with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus 26.0 months with sunitinib (hazard ratio for death, 0.63; P<0.001). The objective response rate was 42% versus 27% (P<0.001), and the complete response rate was 9% versus 1%. The median progression-free survival was 11.6 months and 8.4 months, respectively (hazard ratio for disease progression or death, 0.82; P=0.03, not significant per the prespecified 0.009 threshold). Treatment-related adverse events occurred in 509 of 547 patients (93%) in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group and 521 of 535 patients (97%) in the sunitinib group; grade 3 or 4 events occurred in 250 patients (46%) and 335 patients (63%), respectively. Treatment-related adverse events leading to discontinuation occurred in 22% and 12% of the patients in the respective groups.Conclusions

Overall survival and objective response rates were significantly higher with nivolumab plus ipilimumab than with sunitinib among intermediate- and poor-risk patients with previously untreated advanced renal-cell carcinoma. (Funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ono Pharmaceutical; CheckMate 214 ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02231749 .).Free full text

Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma

Associated Data

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Nivolumab plus ipilimumab produced objective responses in patients with advanced renal-cell carcinoma in a pilot study. This phase 3 trial compared nivolumab plus ipilimumab with sunitinib for previously untreated clear-cell advanced renal-cell carcinoma.

METHODS

We randomly assigned adults in a 1:1 ratio to receive either nivolumab (3 mg per kilogram of body weight) plus ipilimumab (1 mg per kilogram) intravenously every 3 weeks for four doses, followed by nivolumab (3 mg per kilogram) every 2 weeks, or sunitinib (50 mg) orally once daily for 4 weeks (6-week cycle). The coprimary end points were overall survival (alpha level, 0.04), objective response rate (alpha level, 0.001), and progression-free survival (alpha level, 0.009) among patients with intermediate or poor prognostic risk.

RESULTS

A total of 1096 patients were assigned to receive nivolumab plus ipilimumab (550 patients) or sunitinib (546 patients); 425 and 422, respectively, had intermediate or poor risk. At a median follow-up of 25.2 months in intermediate- and poor-risk patients, the 18-month overall survival rate was 75% (95% confidence interval [CI], 70 to 78) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 60% (95% CI, 55 to 65) with sunitinib; the median overall survival was not reached with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus 26.0 months with sunitinib (hazard ratio for death, 0.63; P<0.001). The objective response rate was 42% versus 27% (P<0.001), and the complete response rate was 9% versus 1%. The median progression-free survival was 11.6 months and 8.4 months, respectively (hazard ratio for disease progression or death, 0.82; P = 0.03, not significant per the prespecified 0.009 threshold). Treatment-related adverse events occurred in 509 of 547 patients (93%) in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group and 521 of 535 patients (97%) in the sunitinib group; grade 3 or 4 events occurred in 250 patients (46%) and 335 patients (63%), respectively. Treatment-related adverse events leading to discontinuation occurred in 22% and 12% of the patients in the respective groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall survival and objective response rates were significantly higher with nivolumab plus ipilimumab than with sunitinib among intermediate- and poor-risk patients with previously untreated advanced renal-cell carcinoma. (Funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ono Pharmaceutical; CheckMate 214 ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02231749.)

Sunitinib, a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is a standard of care for first-line treatment of advanced renal-cell carcinoma.1 In a large, randomized, phase 3 trial involving previously untreated patients, the median progression-free survival with sunitinib was 9.5 months, the objective response rate was 25%, and the median overall survival was 29.3 months, with a high rate of hematologic toxic effects.2

The prognosis of patients with advanced renal-cell carcinoma can be categorized according to favorable-, intermediate-, or poor-risk disease depending on the presence of well-characterized clinical and laboratory risk factors.3 A commonly used, validated model to assess prognosis was developed by the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC).4,5 Approximately 75% of patients with advanced renal-cell carcinoma have intermediate- or poor-risk disease and have worse outcomes than those with favorable-risk disease.4,5

Nivolumab, a programmed death 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint inhibitor antibody,6 is approved for the treatment of advanced renal-cell carcinoma after treatment with antiangiogenic therapy, on the basis of an overall survival benefit.7 Ipilimumab, an anti–cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 antibody, is approved for the treatment of metastatic melanoma.8 Although ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg per kilogram of body weight was associated in one trial with an objective response rate of 13% among patients with metastatic renal-cell carcinoma, its toxic effects precluded further development as monotherapy for this disease.9 Combination therapy with nivolumab plus ipilim umab has shown promising efficacy in multiple tumor types, resulting in higher rates of response than either agent alone,10–14 and is approved for the treatment of advanced melanoma.7 The combination has shown antitumor activity in previously untreated and previously treated patients with advanced renal-cell carcinoma, with an objective response rate of 40% and a 2-year overall survival rate of 67 to 70%, depending on the dose.11 Here, we report results from the phase 3 CheckMate 214 trial of nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in previously untreated advanced renal-cell carcinoma.

METHODS

PATIENTS

Eligible patients were 18 years of age or older, with previously untreated advanced renal-cell carcinoma with a clear-cell component. Additional key inclusion criteria were measurable disease according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), version 1.1,15 and a Karnofsky performance-status score of at least 70 (on a scale from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating greater disability).16 Key exclusion criteria were central nervous system metastases or autoimmune disease and glucocorticoid or immunosuppressant use. Patients were characterized according to IMDC risk (favorable [score of 0], intermediate [score of 1 or 2], or poor [score of 3 to 6]), defined according to the number of the following risk factors present: a Karnofsky performance-status score of 70, a time from initial diagnosis to randomization of less than 1 year, a hemoglobin level below the lower limit of the normal range, a corrected serum calcium concentration of more than 10 mg per deciliter (2.5 mmol per liter), an absolute neutrophil count above the upper limit of the normal range, and a platelet count above the upper limit of the normal range.4

TRIAL DESIGN

This was a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial of nivolumab plus ipilimumab followed by nivolumab monotherapy versus sunitinib monotherapy. Randomization (in a 1:1 ratio) was performed with a block size of 4 with stratification according to IMDC risk score (0 vs. 1 or 2 vs. 3 to 6) and geographic region (United States vs. Canada and Europe vs. the rest of the world).

Nivolumab and ipilimumab were administered intravenously at a dose of 3 mg per kilogram over a period of 60 minutes and 1 mg per kilogram over a period of 30 minutes, respectively, every 3 weeks for four doses (induction phase), followed by nivolumab monotherapy at a dose of 3 mg per kilogram every 2 weeks (maintenance phase). Sunitinib was administered at a dose of 50 mg orally once daily for 4 weeks of each 6-week cycle. No dose reductions were allowed for nivolumab or ipilimumab. Dose delays for adverse events were permitted in both groups. Patients treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab had to discontinue both nivolumab and ipilimumab if they had a treatment-related adverse event during the induction phase that required discontinuation, and they could not continue on to nivolumab maintenance therapy. Detailed discontinuation criteria are shown in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

A November 2017 protocol amendment, after the primary end point had been met, permitted crossover from the sunitinib group to the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group. Nivolumab, ipilimumab, and sunitinib were provided by the sponsors, except when sunitinib was procured as a local commercial product in certain countries.

TRIAL OVERSIGHT

This trial was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at each site and was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines, defined by the International Conference on Harmonisation. All the patients provided written informed consent that was based on the Declaration of Helsinki principles. A data and safety monitoring committee reviewed efficacy and safety. The trial was designed by the authors in collaboration with the sponsors (Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ono Pharmaceutical). Bristol-Myers Squibb collected and analyzed the data with the authors. A data confidentiality agreement was in place between Bristol-Myers Squibb and the investigators. The authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and analyses and for the adherence of the trial to the protocol (available at NEJM.org). The development of the first draft of the manuscript was led by the first author and the last three authors; all the authors contributed to drafting the manuscript and provided final approval to submit the manuscript for publication. Medical writing support, funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb, was provided by PPSI.

END POINTS AND ASSESSMENTS

The coprimary end points were the objective response rate, progression-free survival, and overall survival among intermediate- and poor-risk patients. The objective response rate was defined as the percentage of patients having a confirmed best response of complete response or partial response according to RECIST, version 1.1, on the basis of assessment by an independent radiology review committee. Progression-free survival was defined as the time from randomization to first RECIST-defined progression or death. Overall survival was defined as the time from randomization to death.

Secondary end points included the objective response rate, progression-free survival, and overall survival, all in the intention-to-treat population; and the incidence rate of adverse events among all treated patients. Exploratory end points included the objective response rate, progression-free survival, and overall survival, all among favorable-risk patients. Additional exploratory end points included outcomes according to the level of tumor programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression (≥1% vs. <1%), as assessed at a central laboratory with the use of the Dako PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx test, and health-related quality of life on the basis of the score on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Kidney Symptom Index (FKSI-19) (see the Supplementary Appendix), both in intermediate- and poor-risk patients.17,18 FKSI-19 scores range from 0 to 76, with higher scores indicating fewer symptoms.

Disease assessments were performed with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging at baseline, 12 weeks after randomization, continuing every 6 weeks for the first 13 months, and then every 12 weeks until progression or treatment discontinuation. After progression or treatment discontinuation, patients were followed for safety and survival. Adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0.19 Patients in both groups were allowed to continue therapy after initial investigator-assessed, RECIST-defined progression if they had clinical benefit without disabling toxic effects. Patients discontinued trial therapy on evidence of further progression, defined as an additional 10% or greater increase in tumor burden volume from the time of initial progression (including all target lesions and new measurable lesions) according to investigator assessment.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

It was estimated that 1070 patients would undergo randomization, with 820 having IMDC intermediate or poor risk (the proportion expected according to the distribution in the general population and the number needed for robust statistical analyses). Enrollment was discontinued once approximately 820 patients (77%) with IMDC intermediate or poor risk had undergone randomization.

The overall alpha level was 0.05, split among three coprimary end points. The objective response rate was analyzed at an alpha level of 0.001. Progression-free survival was evaluated at an alpha level of 0.009, with a power of 80% or more. We evaluated overall survival at an alpha level of 0.04 with 90% power (independent of coprimary end points) on the basis of a hazard ratio of 0.77, accounting for two formal interim analyses after 51% (reported herein) and 75% of deaths had occurred, using a stratified log-rank test. An O’Brien and Fleming alpha spending function was used to determine nominal significance levels that were based on the number of deaths for the interim and final analyses and stopping boundaries, and an adjusted alpha level of 0.002 was used for the first interim analysis. The critical hazard ratio for the first interim analysis of overall survival was 0.72. The stratified hazard ratio between treatment groups is presented along with the 99.8% confidence interval (adjusted for interim analyses). For progression-free survival, a two-sided stratified 99.1% confidence interval for the hazard ratio was calculated. Confidence intervals were defined on the basis of the respective alpha allocated to that end point. Estimates of response rate, along with the exact two-sided 95% confidence interval by the Clopper–Pearson method,20 were computed. Overall survival, progression-free survival, and duration of response were estimated with the use of Kaplan–Meier methods.

For quality-of-life assessments, descriptive statistics and change from baseline were conducted for the FKSI-19 score. Calculations of P values, to evaluate the between-group difference in mean change from baseline, were based on an independent-samples t-test under the assumption that variances were unequal. Both a pattern-mixture model and a restricted maximum likelihood–based repeated-measures approach were used to confirm descriptive data.

RESULTS

PATIENTS

From October 2014 through February 2016, a total of 1096 patients were randomly assigned to treatment at 175 sites in 28 countries; 1082 patients received treatment (547 with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 535 with sunitinib in the intention-to-treat population; 423 and 416, respectively, had intermediate or poor risk). At the time of the database lock (August 7, 2017), 128 of 547 patients (23%) in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group and 97 of 535 (18%) in the sunitinib group continued treatment (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The primary reason for treatment discontinuation was disease progression, observed in 229 of 547 patients (42%) in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group and 296 of 535 (55%) in the sunitinib group (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Patient characteristics were similar in the two treatment groups, and the characteristics of the intermediate- and poor-risk patients were similar to those of the intention-to-treat population (Table 1). The median follow-up was 25.2 months; the minimum follow-up was 17.5 months.

Table 1

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients Who Underwent Randomization.*

| Characteristic | IMDC Intermediate- and Poor-Risk Patients | Intention-to-Treat Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab (N = 425) | Sunitinib (N = 422) | Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab (N = 550) | Sunitinib (N = 546) | |

|

| ||||

| Median age (range) — yr | 62 (26-85) | 61 (21-85) | 62 (26-85) | 62 (21-85) |

|

| ||||

| Sex — no. (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

Male Male | 314(74) | 301 (71) | 413 (75) | 395 (72) |

|

| ||||

Female Female | 111 (26) | 121 (29) | 137 (25) | 151 (28) |

|

| ||||

| IMDC prognostic risk — no. (%)† | ||||

|

| ||||

Favorable Favorable | 0 | 0 | 125 (23) | 124 (23) |

|

| ||||

Intermediate Intermediate | 334 (79) | 333 (79) | 334 (61) | 333 (61) |

|

| ||||

Poor Poor | 91 (21) | 89 (21) | 91 (17) | 89 (16) |

|

| ||||

| Geographic region — no. (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

United States United States | 112 (26) | 111 (26) | 154 (28) | 153 (28) |

|

| ||||

Canada and Europe Canada and Europe | 148 (35) | 146 (35) | 201 (37) | 199 (36) |

|

| ||||

Rest of the world Rest of the world | 165 (39) | 165 (39) | 195 (35) | 194 (36) |

|

| ||||

| Quantifiable tumor PD-L1 expression — no./ total no. with evaluable data (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

<1% <1% | 284/384 (74) | 278/392 (71) | 386/499(77) | 376/503 (75) |

|

| ||||

≥1% ≥1% | 100/384 (26) | 114/392 (29) | 113/499 (23) | 127/503 (25) |

|

| ||||

| Previous radiotherapy — no. (%) | 52 (12) | 52 (12) | 63 (11) | 70 (13) |

|

| ||||

| Previous nephrectomy — no. (%) | 341 (80) | 319 (76) | 453 (82) | 437 (80) |

|

| ||||

| No. of sites with target or nontarget lesions — no. (%)‡ | ||||

|

| ||||

1 1 | 90 (21) | 84 (20) | 123 (22) | 118 (22) |

|

| ||||

≥2 ≥2 | 335 (79) | 337 (80) | 427 (78) | 427 (78) |

|

| ||||

| Most common sites of metastasis — no. (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

Lung Lung | 294 (69) | 296 (70) | 381 (69) | 373 (68) |

|

| ||||

Lymph node Lymph node | 190 (45) | 216 (51) | 246 (45) | 268 (49) |

|

| ||||

Bone§ Bone§ | 95 (22) | 97 (23) | 112 (20) | 119 (22) |

|

| ||||

Liver Liver | 88 (21) | 89 (21) | 99 (18) | 107 (20) |

EFFICACY

Coprimary End Points in Intermediate- and Poor-Risk Patients

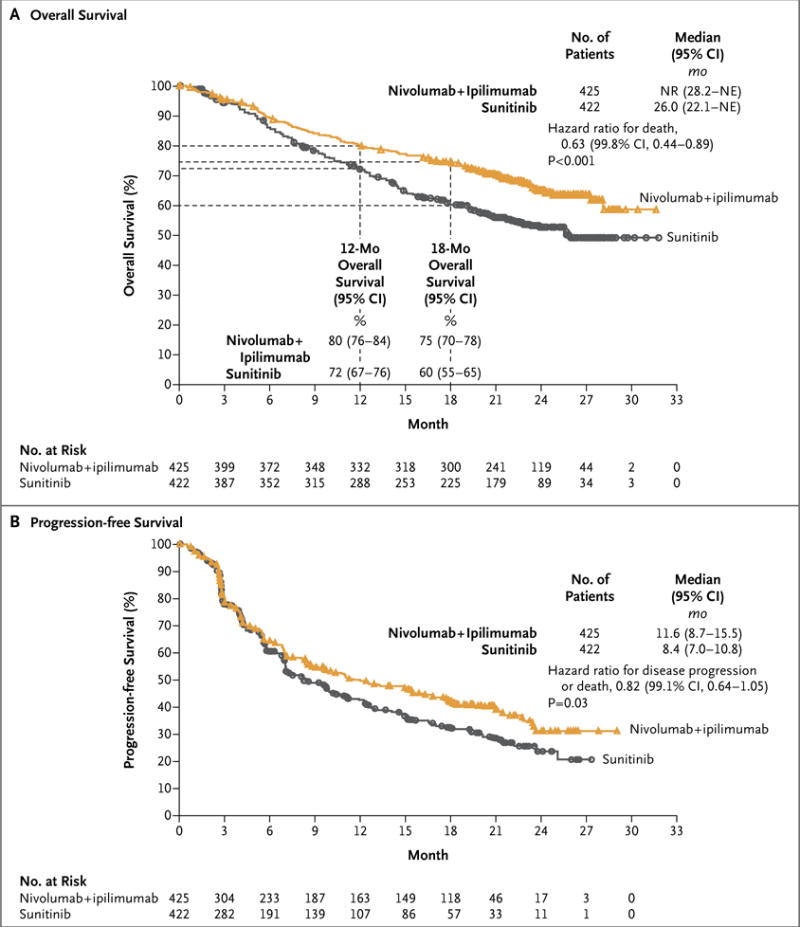

Nivolumab plus ipilimumab had a significant overall survival benefit over sunitinib; the 12-month overall survival rate was 80% (95% confidence interval [CI], 76 to 84) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus 72% (95% CI, 67 to 76) with sunitinib, and the 18-month overall survival rate was 75% (95% CI, 70 to 78) versus 60% (95% CI, 55 to 65) (hazard ratio for death, 0.63; 99.8% CI, 0.44 to 0.89; P<0.001). The median overall survival was not reached (95% CI, 28.2 months to not estimable) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus 26.0 months (95% CI, 22.1 to not estimable) with sunitinib (Fig. 1A).

Progression was defined according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1. For progression-free survival, the between-group difference did not meet the prespecified threshold (P = 0.009) for statistical significance. IMDC denotes International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium, NE not estimable, and NR not reached.

The coprimary end point of objective response rate was 42% (95% CI, 37 to 47) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus 27% (95% CI, 22 to 31) with sunitinib (P<0.001), with complete responses in 40 patients (9%) versus 5 patients (1%) (Table 2). Of all intermediate- and poor-risk patients, 81% of those treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 70% of those treated with sunitinib had a duration of response of at least 1 year, and the median duration of response was not reached (95% CI, 21.8 months to not estimable) and 18.2 months (95% CI, 14.8 to not estimable), respectively (Table 2, and Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Rates of investigator-assessed objective response were consistent with rates of independently assessed objective response (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 2

Antitumor Activity in IMDC Intermediate- and Poor-Risk Patients.*

| Variable | Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab (N = 425) | Sunitinib (N = 422) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Confirmed objective response rate — % (95% CI)† | 42 (37-47)‡ | 27 (22-31)‡ |

|

| ||

| Confirmed best overall response — no. (%)† | ||

|

| ||

Complete response Complete response | 40 (9)ठ| 5 (1)ठ|

|

| ||

Partial response Partial response | 137 (32) | 107 (25) |

|

| ||

Stable disease Stable disease | 133 (31) | 188 (45) |

|

| ||

Progressive disease Progressive disease | 83 (20) | 72 (17) |

|

| ||

Unable to determine or not reported Unable to determine or not reported | 32 (8) | 50 (12) |

|

| ||

| Median time to response (range) — mo | 2.8 (0.9-11.3) | 3.0 (0.6-15.0) |

|

| ||

| Median duration of response (95% CI) — mo | NR (21.8-NE) | 18.2 (14.8-NE) |

|

| ||

| Patients with ongoing response — no./total no. (%) | 128/177 (72) | 71/112 (63) |

For the coprimary end point of progression-free survival, the median was 11.6 months (95% CI, 8.7 to 15.5) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 8.4 months (95% CI, 7.0 to 10.8) with sunitinib (Fig. 1B). The between-group difference did not meet the prespecified threshold (P = 0.009) for statistical significance (hazard ratio for disease progression or death, 0.82; 99.1% CI, 0.64 to 1.05; P = 0.03).

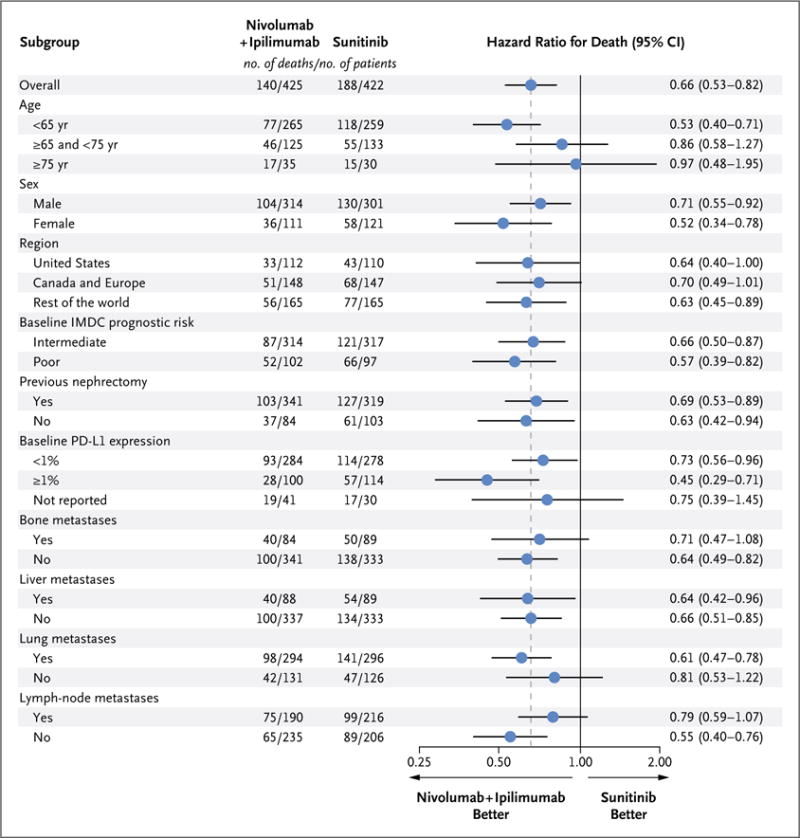

Overall survival favored nivolumab plus ipi limumab over sunitinib across subgroups (Fig. 2). Similarly, the objective response rate was higher with nivolumab plus ipilimumab than with sunitinib in all subgroups (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Patients with intermediate risk had an IMDC score of 1 or 2, and those with poor risk had a score of 3 to 6. IMDC risk scores are defined by the number of the following risk factors present: a Karnofsky performance-status score of 70 (on a scale from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating greater disability; patients with a performance-status score of <70 were excluded from the trial), a time from initial diagnosis to randomization of less than 1 year, a hemoglobin level below the lower limit of the normal range, a corrected serum calcium concentration of more than 10 mg per deciliter (2.5 mmol per liter), an absolute neutrophil count above the upper limit of the normal range, and a platelet count above the upper limit of the normal range. Bone, liver, lung, and lymph-node metastases were not protocol-prespecified subgroups. PD-L1 denotes programmed death ligand 1.

Secondary End Points in the Intention-to-Treat Population

In the intention-to-treat population (patients with favorable, intermediate, or poor risk), the 12-month overall survival rate was 83% (95% CI, 80 to 86) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus 77% (95% CI, 74 to 81) with sunitinib, and the 18-month overall survival rate was 78% (95% CI, 74 to 81) versus 68% (95% CI, 63 to 72). The median overall survival was not reached versus 32.9 months. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab had a significant overall survival benefit over sunitinib (hazard ratio for death, 0.68; 99.8% CI, 0.49 to 0.95; P<0.001). The rate of independently assessed objective response was 39% (95% CI, 35 to 43) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 32% (95% CI, 28 to 36) with sunitinib (P = 0.02, not significant per the prespecified 0.001 threshold). The median progression-free survival was 12.4 months (95% CI, 9.9 to 16.5) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 12.3 months (95% CI, 9.8 to 15.2) with sunitinib. Progression-free survival did not differ significantly between the two groups (hazard ratio for disease progression or death, 0.98; 99.1% CI, 0.79 to 1.23; P = 0.85).

Exploratory Analyses of Favorable-Risk Patients

The baseline characteristics of the 249 favorable-risk patients were similar to those of the intermediate- and poor-risk patients and of the intention-to-treat population, except that the baseline PD-L1 expression level was lower in favorable-risk patients (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). The 12-month overall survival rate was 94% (95% CI, 87 to 97) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 96% (95% CI, 90 to 98) with sunitinib, and the 18-month overall survival rate was 88% (95% CI, 80 to 92) and 93% (95% CI, 87 to 97), respectively (the hazard ratio for death favored sunitinib: 1.45; 99.8% CI, 0.51 to 4.12; P = 0.27). However, only 37 deaths had occurred at the time of the database lock (21 in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group and 16 in the sunitinib group); the median overall survival was not reached and 32.9 months (95% CI, not estimable), respectively. The objective response rate was 29% (95% CI, 21 to 38) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus 52% (95% CI, 43 to 61) with sunitinib (P<0.001), and the median progression-free survival was 15.3 months (95% CI, 9.7 to 20.3) versus 25.1 months (95% CI, 20.9 to not estimable) (hazard ratio for disease progression or death, 2.18; 99.1% CI, 1.29 to 3.68; P<0.001), both favoring sunitinib. However, the rate of complete response was 11% with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 6% with sunitinib.

Exploratory Outcomes According to PD-L1 Expression Level

Among 776 intermediate- and poor-risk patients who had quantifiable PD-L1 expression, 100 of 384 patients (26%) in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group and 114 of 392 patients (29%) in the sunitinib group had 1% or greater PD-L1 expression. In exploratory analyses, overall survival among the 776 patients was longer with nivolumab plus ipilimumab than with sunitinib across PD-L1 expression levels (Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). The 12-month overall survival rate with less than 1% PD-L1 expression was 80% (95% CI, 75 to 84) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 75% (95% CI, 70 to 80) with sunitinib, and the 18-month overall survival rate was 74% (95% CI, 69 to 79) and 64% (95% CI, 58 to 70), respectively; the median overall survival was not reached in both groups (hazard ratio for death, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.96). In patients with 1% or greater PD-L1 expression, the 12-month overall survival rate was 86% (95% CI, 77 to 91) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 66% (95% CI, 56 to 74) with sunitinib, and the 18-month overall survival rate was 81% (95% CI, 71 to 87) and 53% (95% CI, 43 to 62), respectively; the median overall survival was not reached and 19.6 months (95% CI, 14.8 to not estimable), respectively (hazard ratio for death, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.29 to 0.71) (Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

The objective response rate among patients with less than 1% PD-L1 expression was 37% with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 28% with sunitinib (P = 0.03); among patients with 1% or greater PD-L1 expression, the objective response rate was 58% versus 22% (P<0.001) (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). The median progression-free survival among patients with less than 1% PD-L1 expression was 11.0 months with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 10.4 months with sunitinib (hazard ratio for disease progression or death, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.80 to 1.26); among patients with 1% or greater PD-L1 expression, the median progression-free survival was 22.8 and 5.9 months, respectively (hazard ratio for disease progression or death, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.67). A similar trend was observed among patients with 5% or greater PD-L1 expression, as compared with patients with less than 5% PD-L1 expression (not shown).

EXPOSURE AND SAFETY

The median duration of treatment in all patients who received a trial drug was 7.9 months (95% CI, 6.5 to 8.4) with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 7.8 months (95% CI, 6.4 to 8.5) with sunitinib. A total of 79% of the patients received all four doses of ipilimumab with nivolumab. Among the 547 patients treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab, nivolumab dose delays occurred in 319 (58%), and ipilimumab dose delays occurred in 148 (27%). Among the 535 patients treated with sunitinib, dose delays occurred in 315 (59%), and dose reductions occurred in 283 (53%). A total of 157 of 550 patients (29%) in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group and 129 of 546 patients (24%) in the sunitinib group were treated beyond initial investigator-assessed, RECIST-defined progression, as permitted according to the protocol.

Treatment-related adverse events of any grade occurred in 509 of 547 patients (93%) treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 521 of 535 patients (97%) treated with sunitinib (Table 3). Grade 3 or 4 events occurred in 250 patients (46%) and 335 patients (63%) in the respective groups. Treatment-related adverse events leading to discontinuation occurred in 118 of 547 patients (22%) in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group and 63 of 535 patients (12%) in the sunitinib group. Eight deaths in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group and four deaths in the sunitinib group were reported to be treatment-related (Table 3). Of the 436 patients treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab who had a treatment-related select (immune-mediated) adverse event (includes skin, endocrine, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, hepatic, and renal categories), 152 (35%) received high-dose glucocorticoids (≥40 mg of prednisone per day or equivalent).

Table 3

Treatment-Related Adverse Events Occurring in 15% or More of Treated Patients in Either Group.*

| Event | Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab (N = 547) | Sunitinib (N = 535) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Graded† | Grade 3 or 4 | Any Grade‡ | Grade 3 or 4 | |

| number of patients (percent) | ||||

|

| ||||

| All events | 509 (93) | 250 (46) | 521 (97) | 335 (63) |

|

| ||||

| Fatigue | 202 (37) | 23 (4) | 264 (49) | 49 (9) |

|

| ||||

| Pruritus | 154 (28) | 3 (<1) | 49 (9) | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Diarrhea | 145 (27) | 21 (4) | 278 (52) | 28 (5) |

|

| ||||

| Rash | 118 (22) | 8 (1) | 67 (13) | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Nausea | 109 (20) | 8 (1) | 202 (38) | 6 (1) |

|

| ||||

| Increased lipase level | 90 (16) | 56 (10) | 58 (11) | 35 (7) |

|

| ||||

| Hypothyroidism | 85 (16) | 2 (<1) | 134 (25) | 1 (<1) |

|

| ||||

| Decreased appetite | 75 (14) | 7 (1) | 133 (25) | 5 (<1) |

|

| ||||

| Asthenia | 72 (13) | 8 (1) | 91 (17) | 12 (2) |

|

| ||||

| Vomiting | 59 (11) | 4 (<1) | 110 (21) | 10 (2) |

|

| ||||

| Anemia | 34 (6) | 2 (<1) | 83 (16) | 24 (4) |

|

| ||||

| Dysgeusia | 31 (6) | 0 | 179 (33) | 1 (<1) |

|

| ||||

| Stomatitis | 23 (4) | 0 | 149 (28) | 14 (3) |

|

| ||||

| Dyspepsia | 15 (3) | 0 | 96 (18) | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Mucosal inflammation | 13 (2) | 0 | 152 (28) | 14 (3) |

|

| ||||

| Hypertension | 12 (2) | 4 (<1) | 216 (40) | 85 (16) |

|

| ||||

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia | 5 (<1) | 0 | 231 (43) | 49 (9) |

|

| ||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (<1) | 0 | 95 (18) | 25 (5) |

QUALITY OF LIFE

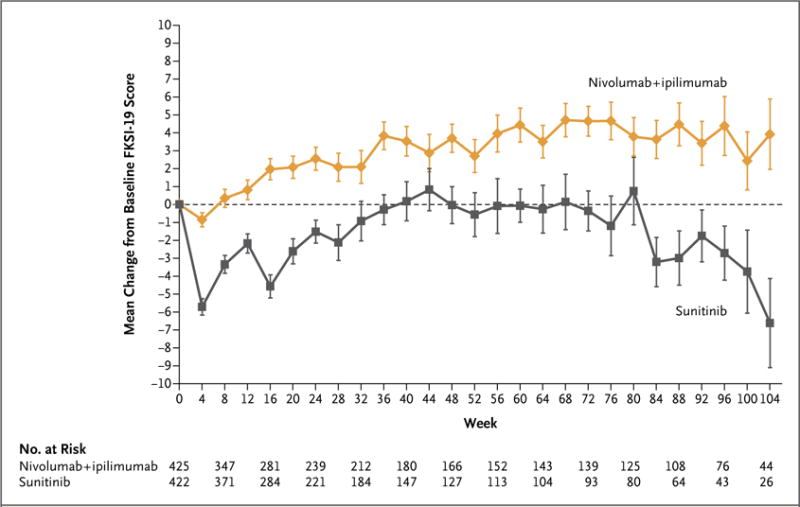

The rate of completion of the FKSI-19 questionnaire exceeded 80% in both groups during the first 6 months. The mean baseline FKSI-19 score (a quality-of-life metric) was similar in the two groups among patients with intermediate or poor risk (60.1 for nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 59.1 for sunitinib); the mean change from baseline was greater in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group than in the sunitinib group at each assessment during the first 6 months (P<0.001) (Fig. 3). The pattern-mixture model and the mixed-model repeated-measures approach indicated a significant difference in favor of nivolumab plus ipilimumab, which substantiated the descriptive results (not shown).

Scores on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Kidney Symptom Index (FKSI-19) range from 0 to 76, with higher scores indicating fewer symptoms. Only time points for which data were available for five or more patients are shown. The number at risk shows the number of randomly assigned patients who were in the trial at each respective time point. I bars indicate standard errors.

SUBSEQUENT THERAPY

Among randomly assigned patients, 217 of 550 (39%) in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group and 295 of 546 (54%) in the sunitinib group received subsequent systemic therapy. The most common subsequent therapies were sunitinib (111 patients, 20%) and pazopanib (72 patients, 13%) in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group and nivolumab (147 patients, 27%) and axitinib (106 patients, 19%) in the sunitinib group.

DISCUSSION

In this randomized, phase 3 trial involving previously untreated patients with advanced renal-cell carcinoma, two of the three coprimary end points were met; among intermediate- and poor-risk patients, the risk of death was 37% lower with nivolumab plus ipilimumab than with sunitinib, and the objective response rate was higher with nivolumab plus ipilimumab (42% vs. 27%). The 9% complete response rate with nivolumab plus ipilimumab compared favorably with the 1% observed with sunitinib and with a complete response rate of 1% or less reported with other tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapies.2,21 A significant difference in overall survival favoring nivolumab plus ipilimumab was also observed in the intention-to-treat population (18-month overall survival rate, 78% [95% CI, 74 to 81] with nivolumab plus ipilimumab vs. 68% with sunitinib [95% CI, 63 to 72]; hazard ratio for death, 0.68; 99.8% CI, 0.49 to 0.95; P<0.001).

Progression-free survival among intermediate-and poor-risk patients was longer with nivolumab plus ipilimumab than with sunitinib but did not meet the prespecified boundary for statistical significance (alpha level, 0.009), partly owing to the distribution of the alpha level across three coprimary end points. The curves separated at 6 months after randomization and followed a pattern similar to that observed in a randomized, phase 3 trial comparing nivolumab with everolimus in previously treated advanced renal-cell carcinoma.22

Longer progression-free survival with nivolumab plus ipilimumab than with sunitinib was observed among patients with 1% or greater PD-L1 expression but not among those with less than 1% PD-L1 expression. In contrast, longer overall survival and a higher objective response rate were observed with nivolumab plus ipilimumab than with sunitinib among intermediate- and poor-risk patients across tumor PD-L1 expression levels, although the magnitude of benefit was higher in the population with 1% or greater PD-L1 expression. This suggests that PD-L1 expression is not entirely predictive of response to and overall survival benefit from the combination, as was also the case with nivolumab monotherapy as second-line treatment, in which a survival benefit was observed across PD-L1 expression levels, and in contrast to published data for sunitinib that showed better outcomes in patients with lower PD-L1 expression levels.22,23

Three quarters of the patients with advanced renal-cell carcinoma have intermediate- or poor-risk clinical features.4 In this trial, 23% of the patients had favorable prognostic risk. The favorable-risk group had a higher objective response rate and longer progression-free survival with sunitinib than with nivolumab plus ipilimumab; these differences did not translate into a significant survival advantage. These results in favorable-risk patients should be interpreted with caution because of the exploratory nature of the analysis, the small subgroup sample, and the immaturity of survival data. However, they highlight the need to better understand the underlying biologic processes driving responses to these two different treatment regimens.

The safety profile of nivolumab plus ipilimumab was consistent with that in previous studies in multiple tumor types, including advanced renal-cell carcinoma,10–12,14,24 with a lower incidence of grade 3 and 4 treatment-related adverse events than observed with sunitinib. The frequencies of treatment-related gastrointestinal, skin, and hepatic adverse events were lower than those seen in a trial involving patients with melanoma, in which a higher dose of ipilimumab (3 mg per kilogram) and a lower dose of nivolumab (1 mg per kilogram) were used.13 Dose delays, treatment with glucocorticoids, and prompt diagnostic workup to rule out noninflammatory causes were used to manage toxic effects according to management algorithms developed for immune-oncology treatment-related adverse events.25 Patients reported better health-related quality of life, as measured by the FKSI-19, with nivolumab plus ipilimumab than with sunitinib.

The approved standard dose of sunitinib was used in this trial, and the data compare favorably with those in previous phase 3 trials of sunitinib.2 Alternate sunitinib schedules, such as 2 weeks on followed by 1 week off, may influence efficacy outcomes, the adverse-event profile, and adherence to therapy, although data from randomized trials are lacking.26

Progress in first-line treatment of renal-cell carcinoma has led to regulatory approval of three antiangiogenic drugs and one mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, although approval was largely due to a benefit with respect to progression-free survival rather than overall survival.27–31 Few studies thus far have been conducted to specifically address the efficacy of these drugs as first-line therapy in intermediate- and poor-risk patients.4,32

This trial showed an efficacy and overall survival benefit of nivolumab plus ipilimumab over sunitinib in the first-line treatment of intermediate- or poor-risk advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ono Pharmaceutical. The authors received no financial support or compensation for publication of this manuscript. Patients treated at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center were supported in part by a Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748).

Dr. Motzer reports receiving grant support and consulting fees from Pfizer, Novartis, Eisai, and Exelixis and grant support from Genentech/Roche; Dr. Tannir, receiving grant support, consulting fees, and honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, receiving grant support from Epizyme and Mirati Therapeutics, receiving grant support, consulting fees, and honoraria from and serving on an advisory board for Exelixis and Novartis, receiving consulting fees and honoraria from Argos Therapeutics and Pfizer, and receiving consulting fees and honoraria from and serving on an advisory board for Eisai, Nektar, and Oncorena; Dr. McDermott, receiving honoraria and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Merck, Novartis, Eisai, Exelixis, Array BioPharma, and Genentech BioOncology and grant support from Prometheus Laboratories; Dr. Melichar, receiving advisory board fees and lecture fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, Novartis, Astellas Pharma, Pfizer, and Bayer; Dr. Choueiri, receiving grant support, paid to his institution, consulting fees, and advisory fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, Genentech, Merck, Novartis, Peloton Therapeutics, Pfizer, Roche, and Eisai, grant support, paid to his institution, from Tracon Pharmaceuticals, and consulting fees and advisory fees from Bayer, Cerulean Pharma, Foundation Medicine, GlaxoSmithKline, Prometheus Laboratories, and Corvus Pharmaceuticals; Dr. Plimack, receiving grant support, paid to her institution, from Acceleron Pharma, AstraZeneca, Aveo Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dendreon, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Peloton Therapeutics, and Pfizer, receiving consulting fees from Acceleron Pharma, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology, Dendreon, Eli Lilly, Exelixis, Genentech/Roche, Glaxo-SmithKline, Horizon Pharma, Inovio Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and SynerGene Therapeutics, receiving fees for the development of educational presentations from Bristol- Myers Squibb, Merck, Novartis, and Roche, holding a pending patent (14/588,503) on methods for screening patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer for neoadjuvant chemotherapy responsiveness, and holding a pending patent (15/226,474) on the combination of an immunomodulatory agent with PD-1 or PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of cancer; Dr. Barthélémy, receiving advisory board fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Novartis, Roche, Ipsen, and Sanofi; Dr. Porta, receiving consulting fees and lecture fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Ipsen, Eisai, and EUSA Pharma, grant support, consulting fees, and lecture fees from Pfizer, and consulting fees from Janssen; Dr. George, receiving consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Exelixis, and Janssen, grant support and consulting fees from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corvus Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Pfizer, and grant support from Celldex Therapeutics and Merck; Dr. Powles, receiving grant support and honoraria from AstraZeneca and Roche, grant support from Novartis, and honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, and Pfizer; Dr. Donskov, receiving grant support from Pfizer and Novartis; Dr. Kollmannsberger, receiving advisory board fees and honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer; Dr. Gurney, receiving advisory board fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, and AstraZeneca and grant support and advisory board fees from Pfizer; Dr. Hawkins, receiving lecture fees from Novartis, Ipsen and Pfizer, lecture fees and travel support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, and royalties for a patent (WO 90/05144) on the phage antibody patent family collectively known as Winter II; Dr. Ravaud, receiving grant support, advisory board fees, and travel support from Pfizer, advisory board fees and travel support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, travel support from Novartis and Merck Sharp & Dohme, and advisory board fees from Roche; Dr. Grimm, receiving grant support, consulting fees, and lecture fees from Novartis and Bristol-Myers Squibb, consulting fees and lecture fees from Pfizer, Bayer HealthCare, and AstraZeneca, lecture fees from Astellas Pharma, Hexal, and Apogepha, and consulting fees from Intuitive Surgical, Sanofi-Aventis, Amgen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and MedUpdate; Dr. Bracarda, receiving consulting fees, lecture fees, and travel support from Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and Janssen, travel support from Novartis and Bayer, consulting fees and travel support from Ipsen, and consulting fees from EUSA Pharma and Merck Sharp & Dohme; Dr. Barrios, receiving grant support and consulting fees from Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmith-Kline, Roche, and Pfizer, grant support from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Mylan, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, Merck, AbbVie, Astellas Pharma, BioMarin Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Abraxis BioScience, Asana BioSciences, AB Science, Medivation, Exelixis, ImClone, LEO Pharma, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, and consulting fees from Eisai; Dr. Tomita, receiving grant support and honoraria from Astellas Pharma and Pfizer, grant support from AstraZeneca, honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, honoraria and consulting fees from Novartis, grant support, honoraria, and consulting fees from Ono Pharmaceutical, and consulting fees from Taiho Pharmaceutical; Dr. Rini, receiving grant support, paid to his institution, and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb; Dr. Chen, being employed by Bristol-Myers Squibb; Drs. Mekan, McHenry, and Wind-Rotolo and Mr. Doan, being employed by and owning stock in Bristol-Myers Squibb; Dr. Sharma, owning stock in Jounce Therapeutics, Kite Pharma, Constellation Pharmaceuticals, and Neon Therapeutics and receiving consulting fees from Merck and Astellas Pharma; and Dr. Escudier, receiving honoraria from Bayer, Novartis, Pfizer, Exelixis, and Roche.

We thank the patients and their families for making this trial possible; Paul Gagnier, the initial medical monitor; Jennifer Mc-Carthy, the CheckMate 214 protocol manager; the staff at Dako for collaborative development of the PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx assay; and Jennifer Granit and Lawrence Hargett of PPSI (a Parexel company) for professional medical writing and editorial assistance with an earlier version of the manuscript.

APPENDIX

The authors’ full names and academic degrees are as follows: Robert J. Motzer, M.D., Nizar M. Tannir, M.D., David F. McDermott, M.D., Osvaldo Arén Frontera, M.D., Bohuslav Melichar, M.D., Ph.D., Toni K. Choueiri, M.D., Elizabeth R. Plimack, M.D., Philippe Barthélémy, M.D., Ph.D., Camillo Porta, M.D., Saby George, M.D., Thomas Powles, M.D., Frede Donskov, M.D., Ph.D., Victoria Neiman, M.D., Christian K. Kollmannsberger, M.D., Pamela Salman, M.D., Howard Gurney, M.D., Robert Hawkins, M.D., Alain Ravaud, M.D., Ph.D., Marc-Oliver Grimm, M.D., Sergio Bracarda, M.D., Carlos H. Barrios, M.D., Yoshihiko Tomita, M.D., Ph.D., Daniel Castellano, M.D., Brian I. Rini, M.D., Allen C. Chen, M.D., Sabeen Mekan, M.D., M. Brent McHenry, Ph.D., Megan Wind-Rotolo, Ph.D., Justin Doan, M.Sc., M.P.H., Padmanee Sharma, M.D., Ph.D., Hans J. Hammers, M.D., Ph.D., and Bernard Escudier, M.D.

The authors’ affiliations are as follows: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York (R.J.M.), and Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo (S.G.) — both in New York; University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston (N.M.T., P. Sharma); Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Dana–Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (D.F.M.), and Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School (T.K.C.), Boston; Centro Internacional de Estudios Clínicos (O.A.F.) and Fundación Arturo López Pérez (P. Salman), Santiago, Chile; Palacký University and University Hospital Olomouc, Olomouc, Czech Republic (B.M.); Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia (E.R.P.); Hôpitaux Universitaires de Strasbourg, Strasbourg (P.B.), Bordeaux University Hospital, Hôpital Saint-André, Bordeaux (A.R.), and Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif (B.E.) — all in France; Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico San Matteo University Hospital Foundation, Pavia (C.P.), and Ospedale San Donato, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale Toscana Sud-Est, Istituto Toscano Tumori, Arezzo (S.B.) — both in Italy; Barts Cancer Institute, Cancer Research UK Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, Queen Mary University of London, Royal Free NHS Trust (T.P.), and Cancer Research UK (R.H.), London; Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark (F.D.); Davidoff Cancer Center, Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, and Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv — both in Israel (V.N.); British Columbia Cancer Agency, Vancouver, Canada (C.K.K.); Westmead Hospital and Macquarie University, Sydney (H.G.); Jena University Hospital, Jena, Germany (M.-O.G.); Centro de Pesquisa em Oncologia, Hospital São Lucas, Porto Alegre, Brazil (C.H.B.); Niigata University, Niigata, Japan (Y.T.); Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid (D.C.); Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland (B.I.R.); Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ (A.C.C., S.M., M.B.M., M.W.-R., J.D.); and Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Baltimore (H.J.H.).

Footnotes

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1712126

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMoa1712126?articleTools=true

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Efficacy and safety of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab as first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma patients: real-world experience in Japan.

Int J Clin Oncol, 30 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39472358

Predicting first-line VEGFR-TKI resistance and survival in metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma using a clinical-radiomic nomogram.

Cancer Imaging, 24(1):151, 11 Nov 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39529158 | PMCID: PMC11552170

Dynamic reciprocal interactions between activated T cells and tumor associated macrophages drive macrophage reprogramming and proinflammatory T cell migration within prostate tumor models.

Sci Rep, 14(1):24230, 16 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39414902 | PMCID: PMC11484957

Increased risk of genitourinary cancer in kidney transplant recipients: a large-scale national cohort study and its clinical implications.

Int Urol Nephrol, 23 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39443429

Balancing Tumor Immunotherapy and Immune-Related Adverse Events: Unveiling the Key Regulators.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(20):10919, 10 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39456702 | PMCID: PMC11507008

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (2,024) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Clinical Trials

- (1 citation) ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT02231749

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: extended follow-up of efficacy and safety results from a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial.

Lancet Oncol, 20(10):1370-1385, 16 Aug 2019

Cited by: 381 articles | PMID: 31427204 | PMCID: PMC7497870

Patient-reported outcomes of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib (CheckMate 214): a randomised, phase 3 trial.

Lancet Oncol, 20(2):297-310, 15 Jan 2019

Cited by: 129 articles | PMID: 30658932 | PMCID: PMC6701190

Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in previously untreated advanced renal-cell carcinoma: analysis of Japanese patients in CheckMate 214 with extended follow-up.

Jpn J Clin Oncol, 50(1):12-19, 01 Jan 2020

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 31633185 | PMCID: PMC6978670

European Medicines Agency extension of indication to include the combination immunotherapy cancer drug treatment with nivolumab (Opdivo) and ipilimumab (Yervoy) for adults with intermediate/poor-risk advanced renal cell carcinoma.

ESMO Open, 5(6):e000798, 01 Nov 2020

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 33188050 | PMCID: PMC7668381

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Bristol-Myers Squibb

NCI NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: P30 CA008748