Abstract

Objective

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM) is a rare developmental lung disease. The aim of this study is to analyze the histomorphological spectrum of CPAM in a series of 15 cases.Materials and methods

A retrospective descriptive study of 15 cases of CPAM was carried out from 2013 to 2018 in our hospital, and cases were classified based on the Stocker's classification.Results

The age ranged from 4 days to 9 years (66.6% were infants). The left lung was most commonly involved (66.6%). The most common lobe was the left upper lobe (60%), followed by right lower lobe (20%). Grossly, cysts measured 0.2-5 cm, filled with mainly serous fluid with few having hemorrhagic and brownish mucoid secretions. On microscopy, single to multiple noncommunicating cysts of size 0.2-5 cm were seen, lined by ciliated columnar epithelium (60%), pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (26.7%), mucin-secreting columnar epithelium (6.7%), and flattened epithelium (6.7%). Few cases showed smooth muscle (20%) and cartilage (13.3%) in the cyst wall. Chronic inflammation (73.3%) with dense histiocytic infiltrate (13.3%) was also seen. Emphysematous changes were also observed (13.3%). Cytomegalovirus inclusions (6.7%), zygomycete fungus (6.7%), and red hepatization (6.7%) were observed. The most common type was type II (60%), followed by type I (33.3%) and type IV (6.7%).Conclusion

Type II was the most common variant in this study. A careful observation should be done to look for fungal hyphae or viral inclusions.Free full text

Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation – A Histomorphological Spectrum of 15 Cases: A 5-Year Study from a Tertiary Care Center

Abstract

Objective:

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM) is a rare developmental lung disease. The aim of this study is to analyze the histomorphological spectrum of CPAM in a series of 15 cases.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective descriptive study of 15 cases of CPAM was carried out from 2013 to 2018 in our hospital, and cases were classified based on the Stocker's classification.

Results:

The age ranged from 4 days to 9 years (66.6% were infants). The left lung was most commonly involved (66.6%). The most common lobe was the left upper lobe (60%), followed by right lower lobe (20%). Grossly, cysts measured 0.2–5 cm, filled with mainly serous fluid with few having hemorrhagic and brownish mucoid secretions. On microscopy, single to multiple noncommunicating cysts of size 0.2–5 cm were seen, lined by ciliated columnar epithelium (60%), pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (26.7%), mucin-secreting columnar epithelium (6.7%), and flattened epithelium (6.7%). Few cases showed smooth muscle (20%) and cartilage (13.3%) in the cyst wall. Chronic inflammation (73.3%) with dense histiocytic infiltrate (13.3%) was also seen. Emphysematous changes were also observed (13.3%). Cytomegalovirus inclusions (6.7%), zygomycete fungus (6.7%), and red hepatization (6.7%) were observed. The most common type was type II (60%), followed by type I (33.3%) and type IV (6.7%).

Conclusion:

Type II was the most common variant in this study. A careful observation should be done to look for fungal hyphae or viral inclusions.

INTRODUCTION

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM) is a developmental disorder of the lower respiratory tract, characterized by the presence of numerous cystic lesions formed due to abnormal airway patterning and branching during lung morphogenesis. CPAM, previously referred to as congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, is a rare condition accounting for about 15%–50% of cases of congenital cystic lung diseases, with an incidence of 1:25,000–1:35,000. This condition is seen mainly in newborns and stillborn infants and is very unusual in infants. It usually presents in neonates with severe, progressive respiratory distress due to expansion of cysts with resultant compression of the surrounding lung parenchyma. Some patients may remain asymptomatic until later in life.[1,2]

CPAM was initially classified by Stocker into three types (type I–III) on the basis of clinical, macroscopic, and microscopic morphology, but later in 2009, two more subtypes (type 0 and type IV) were added.[1] An association of 8.6% has been found between CPAM and malignant lung tumors. Early diagnosis and treatment are required to prevent grave complications such as recurrent infections and malignancy. Imaging examination is important to make an early diagnosis, but histopathological confirmation is required to rule out other cystic lesions.[3,4]

Aims and objectives

The aim of this study is to highlight various histomorphological features of CPAM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective analysis of 15 cases of CPAM was done between 2013 and 2018. The clinicopathological spectrum of all these cases was noted. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained slides of these cases were studied under the microscope, and CPAM lesions were classified according to the Stocker's classification 2009 into five types.

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS

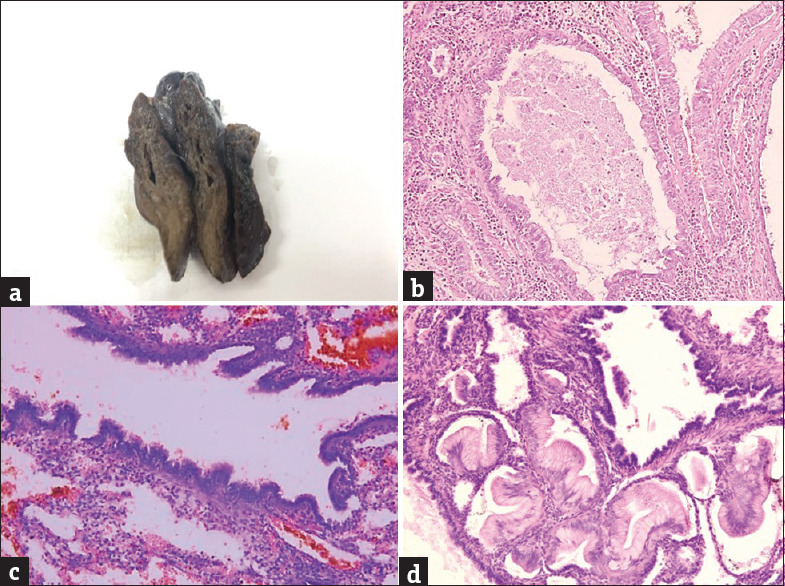

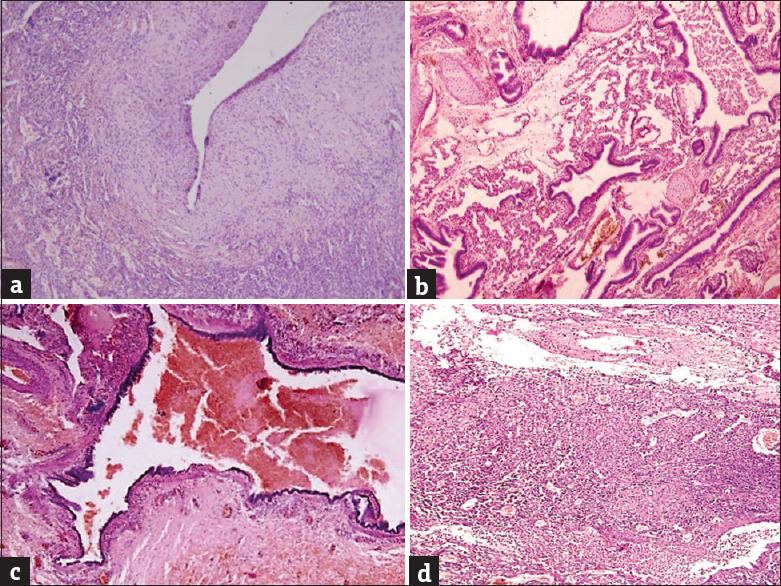

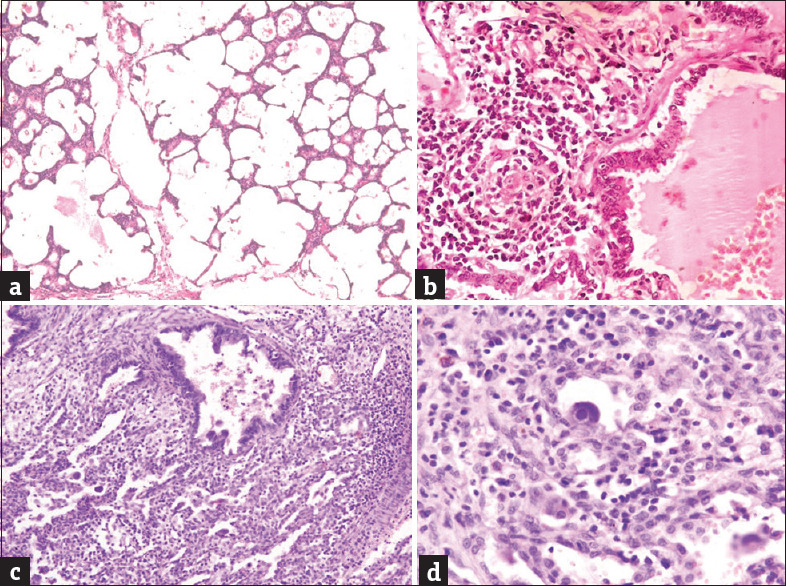

In this study, the age of the CPAM cases ranged from 4 days to 9 years, of which 66.6% of cases were infants, with half of them being neonates. The most common clinical presentations were respiratory distress (especially in infants), and cough and fever, suggestive of lung infection, in children more than 1 year old. Three cases also gave a history of recurrent lung infections and one case presented with failure to thrive at birth. All the cases were diagnosed on computed tomography (CT), which showed multiple noncommunicating hypoechoic cysts suggesting a possibility of cystic lung malformations, possibly CPAM, except one (18-day-old baby) who was diagnosed on antenatal ultrasound. All 15 patients underwent surgical resection of the affected lobe (lobectomy). The left lung was found to be more commonly involved (66.6%) than the right lung. The most common lobe affected was the left upper lobe seen in nine cases (60%), followed by the right lower lobe in three cases (20%) and one case each involving the right upper lobe (6.7%), right middle lobe (6.7%), and left lower lobe (6.7%). Grossly, the specimens were spongy having single to multiple noncommunicating cysts. These cysts ranged in size from 0.2 cm to 5 cm in diameter and were lined by a thin lining, filled with mainly serous fluid with few having hemorrhagic and brownish mucoid secretions [Figure 1a]. On microscopic examination of HE-stained slides, single to multiple noncommunicating cysts were identified ranging in size from 0.2 cm to 5 cm. Most of the cases (60%) showed cysts lined by ciliated columnar epithelium [Figure 1b]. Four cases (26.7%) showed cysts lined by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium [Figure 1c]. Mucin-secreting columnar lining [Figure 1d] was seen in one case (6.7%) and the other one (6.7%) showed cysts lined by flattened lining [Figure 2a]. Cartilage was found in the cyst wall in two cases (13.3%) and smooth muscle component was observed in three cases (20%). Inflammation was present in 11 cases (73.3%) and was mostly composed of chronic inflammatory cells, with two of them showing dense histiocytic infiltrate [Figure [Figure2b2b–d]. Emphysematous changes were observed in two cases (13.3%), with one of them associated with concomitant lung collapse [Figure 3a]. Two cases showed the presence of concomitant superadded infections, evidenced by the presence of endothelial and alveolar cytomegalovirus inclusions in one case and zygomycete fungal infection with features of follicular bronchitis in the other [Figure [Figure3b3b–d]. Areas of red hepatization with many hemosiderin-laden macrophages were also demonstrated in one case. The most common type was type II seen in nine cases (60%), followed by type I in 5 cases (33.3%) and type IV in one case [Table 1].

(a) Gross showing multiple cysts. (b) Cysts lined by ciliated columnar epithelium (H and E, ×200). (c) Cysts lined by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (H and E, ×200). (d) Cysts lined mucin-secreting columnar epithelium (H and E, ×200)

(a) Cysts lined by flattened lining epithelium (H and E, ×200). (b) The presence of cartilage in the cyst wall (H and E, ×200). (c) The presence of smooth muscle in the cyst wall (H and E, ×200). (d) The presence of suppuration (H and E, ×200)

(a) Emphysematous change (H and E, ×200). (b) Follicular bronchitis (H and E, ×200). (c) Secondary suppuration with intra-alveolar cytomegalovirus inclusions (H and E, ×200). (d) Intra-alveolar cytomegalovirus inclusion (H and E, ×400)

Table 1

Histopathological features based on the Stocker’s classification

| Lobe | Gross | Epithelial lining | Cartilage | Smooth muscle | I/M* | H’G** | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUL | Single cyst (2 cm) with hemorrhagic material | Ciliated columnar | - | - | Chronic | + | Type II |

| RLL | Multiple cysts (1-5 cm), focally grey white | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar | + | + | Chronic (histiocytic) | - | Type I |

| LUL | Spongy, multicystic (0.5-2 cm) | Ciliated columnar | - | - | Chronic | - | Type II |

| LUL | Small cystic (0.2-1 cm) | Ciliated columnar | - | - | - | - | Type II emphysematous changes, antenatally diagnosed |

| LUL | Multiple cysts (0.5-4 cm) | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar | + | + | - | - | Type I |

| RML | Single cyst (2 cm) filled with mucoid material | Ciliated columnar | - | - | - | - | Type II emphysematous changes, collapse |

| LUL | Single cyst (3.5 cm) | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar | - | + | Chronic | + | Type I interstitial fibrosis |

| LLL | Multiple cysts (0.6-4 cm) | Flattened lining | - | - | Chronic (histiocytic) | - | Type IV alveolar and endothelial CMV inclusions |

| RLL | Multiple cysts (0.2-3.5 cm) filled with mucoid and brownish material | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar | - | - | Neutrophilic | - | Type I secondary suppuration |

| LUL | 2 cysts (1-1.8 cm) | Ciliated columnar | - | - | Acute on chronic | - | Type II |

| LUL | Lump identified, cyst | Mucin-secreting columnar | - | - | Chronic | - | Type I, hemosiderin laden macrophages, red hepatization |

| LUL, left lingular lobe | No cyst | Ciliated columnar | - | - | Chronic | - | Type II, zygomycosis, small cysts (0.2-0.8 cm), follicular bronchitis |

| LUL | Multiple grey white soft tissue bits | Ciliated columnar | - | - | Chronic | - | Type II |

| LUL | Few cysts (0.5-4 cm) | Ciliated columnar | - | - | - | - | Type II |

| RLL | Solid cystic (0.5-1.5 cm) | Ciliated columnar | - | - | Chronic | - | Type II |

*Inflammation, **Hemorrhage. RUL: Right upper lobe, RLL: Right lower lobe, LUL: Left upper lobe, LLL: Left lower lobe, RML: Right middle lobe, CMV: Cytomegalovirus

DISCUSSION

CPAM is a rare condition accounting for about 15%–50% of cases of congenital cystic lung diseases, with an incidence of 1:25,000–1:35,000. This condition is seen mainly in newborns and stillborn infants and is very unusual in infants.[1,2] In this study, 66.6% of cases were infants, with 50% of them being neonates. The remaining five cases were between 4 years and 9 years of age. Males were affected more than females similar to other studies.[5,6,7]

The pathogenesis of CPAM is not clear, but the accepted theory is that an abnormal airway patterning and branching during lung morphogenesis leads to appearance of lung cysts. Some authors also favor an arrest in the development of fetal bronchial tree to be the cause. Normal lung development begins at 3–4 weeks in utero and passes through six stages: embryonic stage, pseudoglandular stage, canalicular stage, saccular stage, alveolar stage, and finally, the microvascular stage, that continues from birth to 2–3 years of age. It is the arrest at these stages of development that may lead to CPAM (pseudoglandular stage arrest leads to type I, II, and III CPAM, and saccular stage arrest leads to type IV CPAM). There are few suspected factors that might play a role in CPAM by increasing cellular proliferation and reducing apoptosis. These factors are thyroid transcription factor, glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor, increased levels of Hoxb-5, FGF9, Clara cell marker 10, and Sox 2, and decreased expression of FGF7 and fatty acid-binding protein.[3]

The clinical manifestations vary from asymptomatic cases to recurrent pneumonia, respiratory distress, or even acute respiratory failure.[1] In this study, infants usually presented with respiratory distress, and children above 1 year of age presented with cough and fever. Similar findings were seen in the studies conducted by Zhang and Huang and Maneenil et al.[6,8] [Table 2].

Table 2

Correlation of this study with other studies

| Review of studies | Number of cases studied | Mean age of presentation (months) | Most common lobe involved (%) | Most common type based on the Stocker’s classification (%) | Most common presentation (%) | Recurrent lung infection, n (%) | Male: female ratio | Chronic inflammation on microscopy, n (%) | Mucous cells, n (%) | Cartilage, n (%) | Complications, n (%) | Associated anomalies and malignancies, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our study | 15 | 25.6 | LUL (60) | Type II (60) | Respiratory distress (66.6) | 3 (20) | 2:1 | 9 (60) with histiocytic infiltrate in two of them | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | Zygomycete infection – 1 (6.7) CMV infection – 1 (6.7) Emphysema – 2 (13.3) | 0 (0) |

| Kini et al. (2019)[9] | 15 (5- antenatal, 10- postnatal) | 34.8 (postnatal cases) (26.8 weeks in antenatal cases) | Right lung (53.3) with RML (37.5), RLL (37.5), RUL (25) | Type I (46.7) | Cough, fever, dyspnea | 1:1.1 | 7 (46.7) | 1 (6.7) | Emphysematous change 2 (13.3) | |||

| Maneenil et al. (2019)[8] | 27 | 4.9 | RLL (51.8) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Singh et al. (2018)[5] | 5 | 33.6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4:1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang and Huang (2015)[6] | 11 | 32.4 | Right lung (45.4) (lobe not specified) | Type I (54) | Recurrent respiratory tract infection, coughing, fever | NA | 1.2:1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Giubergia et al. (2012)[7] | 172 | 48 | RLL (38) | Type I (70) | NA | 76 (44.2) | 1.1:1 | 71 (41) | 1 (0.6) | NA | Bronchiectasis 18 (10) | Anomalies 81 (47) Malignancies 2 (1.2) |

RUL: Right upper lobe; RLL: Right lower lobe; LUL: Left upper lobe; RML: Right middle lobe; NA: Not applicable, CMV: Cytomegalovirus

Except one case whose lesions were picked up on antenatal ultrasound, all other cases were diagnosed postnatally on CT scan. The reason could be that no antenatal scan was done, or the lesion might not have developed by the second trimester, or was missed. Antenatal ultrasound stands as an indispensable, safe, and cost-effective tool for suspecting CPAM lesions in which CPAM appears as a hyperechoic, heterogeneous tissue with cystic (type I, II, and IV) or solid (type III) intrathoracic lesion. It also tells the anatomical location of the lesion, its relationship with bronchial tree, number and size of the cysts, any coexisting anomaly such as pulmonary sequestration, and presence of hydrops fetalis and mediastinal shift, thus prognosticating the disease. The prognosis of CPAM largely depends on the presence or absence of hydrops fetalis with a survival rate of <5% in cases with hydrops fetalis. This can be assessed by measuring mass-to-thorax ratio (MTR) and CPAM volume ratio (CVR), which is the ratio of CPAM volume to fetal head circumference. An MTR of 0.56, CVR >1.6, cystic predominance, and diaphragmatic inversion predict an increased risk of hydrops fetalis.[3,10]

On radiological examination, all lesions were unilateral. The left lung was found to be affected more than the right lung, with the left upper lobe being the most common lobe. These results are in contrast to the studies performed by Zhang et al., Giubergia et al., Maneenil et al., and Kini et al. in which the right lung was more commonly affected[6,7,8,9] [Table 2]. Laterality is important as it has been postulated that left-sided unilateral cases tend to be worse.[7]

After radiological examination, however, due to varied clinical and radiological presentations of CPAM, and in order to differentiate them other congenital cystic lung lesions such as pulmonary sequestration, bronchogenic cyst, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, congenital lobar overinflation, simple foregut cyst, primary ciliary dyskinesia, and cystic fibrosis, histopathological confirmation of the lesion becomes imperative.[1] [Table 3].

Table 3

Differential diagnosis of congenital pulmonary airway malformation[1]

| Differential diagnosis | Differentiating features |

|---|---|

| Bronchogenic cyst | Absence of cartilage in CPAM |

| Simple foregut cyst | Absence of distinctive rows of mucous cells in CPAM |

| PS | Anomalous blood supply from systemic circulation and no communication with the normal functioning lung in PS |

| Congenital lobar overinflation | Normal lung histopathology, mild alveolar dilation, no destruction of alveolar septa |

| PCD | Bronchial dilation secondary to mucus retention due to ciliary dysfunction in PCD |

| CF | Bronchiectasis secondary to obstruction and secondary infection |

PS: Pulmonary sequestration, PCD: Primary ciliary dyskinesia, CF: Cystic fibrosis, CPAM: Congenital pulmonary airway malformation

Based on clinical, gross, and microscopic findings, CPAM, in 1977, was classified by Stocker into three types (type I to III) and was differentiated from normal lung by the presence of cystic structures, increased smooth muscle and elastic tissue in the cyst wall, mucosal polypoidal projection, absence of cartilage and inflammation, and presence of mucus-secreting cells. This classification got modified later in 2009. In this current classification, type 0 (acinar dysplasia), seen in 1%–3% of cases, presents at birth and is incompatible with life. All lobes are involved and consist of small cysts (0.5 cm) lined by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium and goblet cells with numerous bronchiolar cartilage and muscle. Type I (60%–65%) consists of multiple large cysts (3–10 cm) lined by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium along with mucinous cells (seen in 33% of cases), occasional bronchiolar cartilage, and muscle. It usually presents in newborns, is operable, and carries good prognosis. Type II (10%–15%) consists of medium-sized cysts (0.5–2 cm), giving spongy appearance to the lung, lined by ciliated cuboidal/columnar epithelium. No mucinous cells/cartilage are seen. It usually presents in the 1styear of life and affects one lobe. It is associated with congenital anomalies and carries a poor prognosis. Type III (8%) is solid cystic, usually involving one lobe with stellate-shaped bronchiole giving adenomatoid appearance, with cysts lined by ciliated columnar epithelium, without mucinous cells/cartilage/muscle. It presents in utero or at birth and carries a poor prognosis. Type IV (10%–15%) consists of large cysts (7 cm) lined by flattened lining epithelium with the rare absence of mucous cells and cartilage. It presents in newborns as respiratory distress, pneumothorax, or pneumonia.[1]

Type I has the highest incidence (60%–65%), followed by type II and type IV, each having a frequency of 10%–15%.[1] Zhang et al., Giubergia et al., and Kini et al. also found type I as the most common type[6,7,9] [Table 2]. In this study, however, type II was found to be the most common presentation accounting for 60%, followed by type I (26.6%) and type IV (6.6%), which might point toward demographic variation of the lesion.

Diagnosis of type I was made in four cases based on clinical presentation respiratory distress, macroscopic examination showing the presence of single to multiple noncommunicating cysts ranging in size from 0.2 cm to 5 cm, and histological examination showing the presence of cysts lined by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium and mucus-secreting cells in one of them, presence of cartilage in one case, and smooth muscle in the cyst wall in two cases.

Diagnosis of type II CPAM was made in nine cases by macroscopic examination showing spongy appearance with the presence of single to multiple small noncommunicating cysts ranging in size from 0.2 cm to 4 cm and histological examination showing the presence of cysts lined by ciliated columnar epithelium and absence of cartilage and smooth muscle in the wall. Two cases demonstrated the presence of emphysematous changes and one case showed the evidence of superadded zygomycete fungal infection. However, no signs of immunosuppression were observed in these patients.

Diagnosis of type IV was made in only one case showing the presence of multiple cysts ranging in size from 0.6 cm to 4 cm on gross examination and histological examination revealing multiple cysts lined by flattened lining epithelium and absence of cartilage and smooth muscle in the cyst wall. This case demonstrated the presence of alveolar and endothelial cytomegalovirus inclusions despite being immunocompetent.

The role of histopathology also lies in ruling out an associated increase risk (8.6%) of malignant transformation in CPAM.[3] Type 1 CPAM, through a sequence of mucous hyperplasia and atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, can progress to lepidic-type adenocarcinoma by acquiring KRAS mutation. Risk of developing mucoepidermoid carcinoma is increased. Early resection of asymptomatic CPAM lesion is thus advised to prevent uneventful complications.[9] Similarly, type II may involve malignant transformation to rhabdomyosarcoma and type IV CPAM to pleuropulmonary blastoma.[2,9] CPAM is also associated with other congenital malformations such as bilateral renal agenesis, extralobar pulmonary sequestration, cardiovascular malformation, and diaphragmatic hernia.[10,11] In this study, none of the cases had associated malignancies and congenital anomalies.

Surgical resection holds the treatment of choice in symptomatic cases. The management of asymptomatic cases remains contentious. Some authors prefer surgical intervention in order to prevent associated complications such as malignancies and recurrent lung infections, while others prefer a conservative approach and postponing the surgery to avoid the surgical risk of morbidity.[8]

CONCLUSION

The study highlights various histomorphological features of CPAM. In contrast to most of the studies, type II was found to be the most common type which might suggest a demographic variation in histological types. CPAM, especially types II and IV, can get complicated by emphysematous changes and superadded infections, which warrants a careful search. This is a rare study evidencing the presence of superadded zygomycete fungal and cytomegalovirus infection in the immunocompetent patients of CPAM. CPAM needs to be ruled out in young children (5–10 years old) presenting with recurrent lung infections. A careful antenatal screening should be performed to diagnose these lesions at the earliest to avoid uneventful complications later in life. CPAM cases can be managed by early diagnosis in utero using radiological assistance and treatable by surgical intervention.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Articles from Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons are provided here courtesy of Wolters Kluwer -- Medknow Publications

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/119225799

Article citations

A case of cytomegalovirus cystic lung disease and review of literature.

Respirol Case Rep, 12(10):e70054, 21 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39439885 | PMCID: PMC11493753

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

[Cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung in an adult].

Minerva Chir, 52(4):469-473, 01 Apr 1997

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 9265134

Review

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation: A report of two cases.

World J Clin Cases, 3(5):470-473, 01 May 2015

Cited by: 11 articles | PMID: 25984523 | PMCID: PMC4419112

An Atypical Presentation of Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation (CPAM): A Rare Case with Antenatal Ultrasound Findings and Review of Literature.

Pol J Radiol, 82:299-303, 04 Jun 2017

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 28638495 | PMCID: PMC5467709

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation: CT-pathologic correlation.

J Thorac Imaging, 22(2):149-153, 01 May 2007

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 17527118