Abstract

Free full text

A New Class of Selective ATM Inhibitors as Combination Partners of DNA Double-Strand Break Inducing Cancer Therapies

Abstract

Radiotherapy and chemical DNA-damaging agents are among the most widely used classes of cancer therapeutics today. Double-strand breaks (DSB) induced by many of these treatments are lethal to cancer cells if left unrepaired. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) kinase plays a key role in the DNA damage response by driving DSB repair and cell-cycle checkpoints to protect cancer cells. Inhibitors of ATM catalytic activity have been shown to suppress DSB DNA repair, block checkpoint controls and enhance the therapeutic effect of radiotherapy and other DSB-inducing modalities. Here, we describe the pharmacological activities of two highly potent and selective ATM inhibitors from a new chemical class, M3541 and M4076. In biochemical assays, they inhibited ATM kinase activity with a sub-nanomolar potency and showed remarkable selectivity against other protein kinases. In cancer cells, the ATM inhibitors suppressed DSB repair, clonogenic cancer cell growth, and potentiated antitumor activity of ionizing radiation in cancer cell lines. Oral administration of M3541 and M4076 to immunodeficient mice bearing human tumor xenografts with a clinically relevant radiotherapy regimen strongly enhanced the antitumor activity, leading to complete tumor regressions. The efficacy correlated with the inhibition of ATM activity and modulation of its downstream targets in the xenograft tissues. In vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated strong combination potential with PARP and topoisomerase I inhibitors. M4076 is currently under clinical investigation.

Introduction

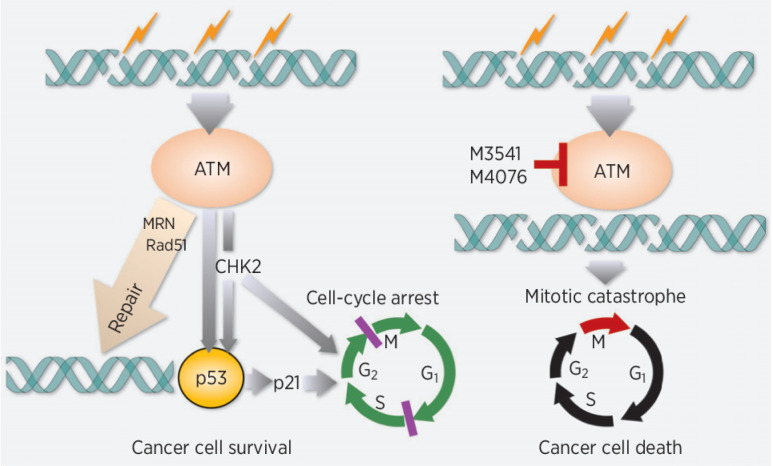

Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) is a serine/threonine kinase that plays a key role in the DNA damage response (DDR; refs. 1, 2). ATM acts as an upstream signaling kinase (3), involved directly or indirectly in several aspects of DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair, including homologous recombination (HR), non-homologous end-joining, and cell-cycle regulation. Following induction of DSBs by a variety of endogenous and exogenous insults, ATM undergoes re-localization and catalytic activation. A portion of nuclear ATM is rapidly recruited to sites of DNA damage and becomes an active component of the protein complex associated with DSBs (4). There, it orchestrates a complex set of protein interactions engaged in the execution of HR repair of DSBs. Although limited to the fraction of the cells residing in late S or G2 phase, ATM-driven HR repair allows for error-free restoration of broken DNA and is critical for long-term cell survival. In response to DSBs in nuclear DNA, ATM takes control of the cell-cycle checkpoint machinery to protect mammalian cells from catastrophic consequences of DNA damage (5).

Inhibitors of ATM kinase activity are expected to delay DSB repair, leading to persistent DSBs. Moreover, they may impair ATM-mediated cell-cycle arrest (6) and proper functioning of the mitotic spindle (7, 8). As a result, ATM inhibition could enhance the antitumor effect of DSB-inducing treatment modalities, including radiotherapy and DNA-damaging chemotherapy (9). Therefore, ATM has emerged as a desirable intervention point in DDR and several small-molecule inhibitors that suppress its activity have been reported, including molecules in clinical development (10–15).

Here, we describe two highly potent and selective ATM inhibitors with optimized pharmacological properties, M3541 and M4076, from a new chemical class. Preclinical profiling in cell-free and cell-based assays showed that they effectively suppress ATM catalytic activity and function in DDR and strongly sensitize a broad range of cancer cell lines to ionizing radiation. Efficacy studies in clinically relevant mouse models of fractionated radiotherapy demonstrated a strong enhancement of radiotherapy efficacy and complete regression of human tumor xenografts. Cell-based growth/viability screens of M4076 with a large panel of antitumor agents identified PARP and topoisomerase I inhibitors as the most synergistic combination partners. Their combination efficacy was confirmed in xenograft studies supporting further clinical investigation.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

Various batches of M3541 and M4076 were synthesized by the Medicinal Chemistry Department at the healthcare business of Merck KGaA (16, 17). M3541 is disclosed as compound 36 in patent application WO2012028233 (16) and M4076 as compound 1 in patent application WO2020193660 (18). Infusion solution of Cisplatin (50 mg/100 mL) was from Medac GmbH. Niraparib tosylate and rucaparib camphorsulfonate were purchased from BOC Sciences. Hydroxyurea was obtained from MiliporeSigmaS, bleomycin sulfate from Calbiochem, and irinotecan from cell pharm Stada GmbH. Cell lines were purchased from the ATCC, DSMZ or ECACC, and cultured in the recommended media supplemented with serum as follows: A375, HCC-1187, HT-144, MDA-MB-468, NCI-H1975, NCI-H460: RPMI-1640/10% FCS/2 mmol/L glutamine/1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate/5% CO2; Capan-1: DMEM/15% FBS/10% CO2; A549: AGS, FaDu, GRANTA-519, HT-29, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231: DMEM/10% FCS/10% CO2; MDA-MB435: DMEM/F12/10% FCS/2 mmol/L glutamine/1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate/ 1% Non-essential amino acids/5% CO2; HCT-15, NCI-H23, NCI-H1395: RPMI-1640/10% FCS/2 mmol/L glutamine/1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate/2.5 g/l glucose/5% CO2; HCT116: MEMα GlutaMAX/10% FCS/10% CO2; LoVo: Ham's F12/10% FCS/10% CO2; RKO: MEM Eagle/10% FCS/2 mmol/L glutamine/1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate/1% Non-essential amino acids/10% CO2; SW620: DMEM/F12/2 mmol/L glutamine/10% FCS/ 10% CO2. Cell line identity was confirmed by short tandem repeat analysis. Mycoplasma infection was excluded by testing periodically using a PCR-based method.

Kinase activity assays

ATM, ATM and rad3-related (ATR)/ATR-interacting protein assays, and DNA-PK assays were performed using TR-FRET as previously described (19). Protein and lipid kinase profiling was performed at Eurofins (Dundee, UK; ref. 20). Recombinantly produced protein and lipid kinases were used in enzyme activity assays. Protein kinase reactions were assayed in a radiometric format whereas lipid kinases were assayed using a TR-FRET format. The “percentage of effect” activity was determined compared with vehicle-treated controls corrected for background activity. M3541 is tested at 1 μmol/L or serially diluted for IC50 determination.

Western blot analyses

A549 cells were grown in 75-cm flasks for 24 hours before treatment. Cell were lysed in 2x Laemmli buffer (4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20% glycerol and 120 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Samples were resolved by NuPAGE 4%–12% Bis-Tris Midi Gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. Western blots were developed with SuperSignal Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 34580) and analyzed by GE ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare). The primary antibodies used were from Abcam: pATM (S1981; ab81292), ATM (ab199726), pKAP1(Ser824; ab133440), KAP1 (ab22553), and Cell Signaling Technology: p-p53 (Ser15; 9284S), p53 (48818S), pCHK2 (T68; 2197S), CHK2 (3440S), horseradish peroxidase–conjugated GAPDH (3683).

Immunofluorescence studies

Proliferating A549 cells were seeded in 8-well glass slides (Millipore, PEZGS0816) and treated as indicated. Cells were treated with fixing solution (1% paraformaldehyde, 2% sucrose in PBS) for 15 minutes at room temperature followed by ice-cold methanol (−20°C) for 30 minutes, and methanol/acetone for 20 minutes. Cells were blocked with MAXblock Medium (Active Motif, 15252), and incubated with the indicated primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed and incubated with secondary antibodies and DAPI (Invitrogen, D1306) for 1 hour. Cells were then mounted onto glass cover slides with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen, P36934) and images were taken using a Zeiss MIC-074 fluorescence microscope. γH2AX foci counting was performed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). DAPI staining was used to generate a nuclear mask that defines foci within each nucleus. γH2AX staining was set up using maxima/foci detection with a noise tolerance of 15. Primary antibodies for γH2AX (Cell Signaling Technology, 9718) and secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, A11034).

Colony formation assay

Exponentially proliferating cancer cells were seeded in multiwell plates and 24 hours later exposed to IR (Faxitron RX-650 irradiator) alone or in combination with a concentration range of the inhibitors added 1h before radiotherapy. After an additional 24 hours in the presence of inhibitors, the cell media were replaced with fresh drug-free culture media and incubated for several days to weeks until visible colonies were formed. Cell colonies were stained with neutral red or crystal violet and counted by a Gelcount Scanner (Oxford Optronix). Cell counts were normalized to DMSO controls without IR. Concentration-response curves were fitted using a nonlinear regression method to determine IC50 values.

IncuCyte live-cell imaging

A549 NucLight cells were purchased from Essen Bioscience (4492) and maintained according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 overnight. The next day, cells were pre-treated with M3541 for 1 hour followed by IR (5 Gy). Images were taken every 2 hours over a 6-day period using the ×10 objective with IncuCyte ZOOM (Essen Bioscience). Cell growth curve was plotted on the basis the number of green, fluorescent nuclei for 6 days.

ELISA and cellular kinase assays

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. On the next day a serial dilution of M3541 inhibitor and bleomycin (10 μmol/L) were added and incubated for additional 3–6 hours at 37°C. Compounds were tested in singlicate together with respective controls on the same plate. Cells were lysed in HGNT lysis buffer (20 mmol/L HEPES pH 7.4, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 25 mmol/L NaF, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails and pCHK2 (Thr68) was analyzed using a Sandwich ELISA (PathScan pCHK2 (Thr68), Cell Signaling Technology. Absorbance 450 nm was quantified using Tecan Sunrise (Tecan) or Victor 3 reader (PerkinElmer). For M4076 cells were treated with a serial dilution of M4076 1 hour before 2 Gy IR. Cell lysates were prepared 1 hour after radiotherapy as above and analyzed pATM and pCHK2 (Thr68) using the Luminex assay format. For pATM, Capture: ATM (Abcam, ab2618); Detection: ATM (Abcam, ab59541), pATM(S1981; Abcam, ab208775). For pCHK2(Thr68), Capture: CHK2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 6334); Detection: CHK2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 3440), pCHK2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 2197). Beads were analyzed using the MAGPIX instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Phosphorylated proteins were normalized to total protein. Data were analyzed by log(inhibitor) versus response Variable slope to determine IC50 values.

Cancer cell line screening

The effect of M3541 on the response of cancer cells to IR (3 Gy) was tested in a panel of 79 cancer cell lines at Oncolead. The cell viability was determined after radiotherapy alone or the combination of 3 Gy IR (Cobalt-60 source) and a range of M3541 concentrations (5–5,000 nmol/L). Treated cells were incubated for 120 hours, fixed, stained with sulforhodamine B (SRB), and quantified colorimetrically (21). GI50 values were calculated from the concentration response data as previously described (19). Bliss independence was used to calculate synergy (22). In brief, the Bliss independence method compares the observed effect size Emeasured of a drug combination with the calculated effect, with Ecalc assuming complete independence of the drug effects (Ecalc = EDrug1 + EDrug2 – EDrug1EDrug2). Calculated Bliss values represent the mean values from all concentration combinations of a specific drug combination that we classified the following: Strong synergy >0.1; 0.1≥ weak to moderate additivity/antagonism ≥−0.1; strong antagonism <−0.1.

The drug combination screen was run with a subset of 34 cancer cell lines at Oncolead as previously described (19). A collection of 79 test compounds comprised of approved/investigational drugs and preclinical stage chemical compounds representing the main classes of anticancer mechanisms was used. Cell viability was determined for a concentration range of all 79 drugs previously determined on the base of their potency in the presence or absence of a fixed concentration of 1 μmol/L M4076 after 120 hours incubation period by SRB staining (21). Combination effects for the different compound combinations are calculated under the assumption of independent modes of action of the combination partners using the BLISS independence model (23). Excess over the linear combination of the monotherapy treatments effects E1 and E2 is calculated as: Etheo = E1+E2-E1E2 (theoretical combination effect); Excess = Eobs − Etheo (excess over theoretical combination effect). The combination effects (BLISS excess) have been averaged across all individual concentrations for each individual combination treatment. Positive combinations effects (BLISS excess > 0) are considered synergistic.

In vivo studies

The study designs and animal usage for the cell line derived xenograft studies (FaDu, NCI-H1975, Capan-1, NCI-H460, SW620) were approved by local animal welfare authorities (Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt, Germany, protocol numbers DA4/Anz. 397, DA4/Anz. 398, and DA4/Anz.1014). Female 7–9-week-old immunodeficient mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, NMRI mice for FaDu model, CD1 mice for Capan-1, NCI-H1975, FaDu models, or Taconic Biosciences (Denmark) H2d Rag2 [C;129P2-H2d-TgH(II2rg)tm1Brn-TgH(Rag2)tm1AltN4] for SW620 model. Mice received subcutaneous injections of the respective cell lines either in the flank or thigh followed by irradiation (total doses >10Gy). Cell number: 2–3×106 FaDu, 3×106 Capan-1, 2.5×106 NCI-H1975 and NCI-H460 and 4×106 SW620. Cells were injected in 100 μL PBS/ Matrigel (BD MatrigelTM Matrix; 1:1; thigh) or PBS only (flank). Mice with established xenografts were randomized (n = 9–10 from 15 mice/arm) to obtain a similar mean and median within treatment groups (starting volume varies between studies and is reflected in the respective figures (TV on d0).

The HBCx-9 patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model was established from human breast cancer specimens and maintained by serial transplantation into immunodeficient mice (24). All in vivo experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the French Ethics Committee (Agreement D-91–228–107) and approved by the French animal welfare authorities (APAFIS#7125–2016012713169445v3, APAFIS#19260–2019021311503803v1). Female athymic nude mice, 6–8-weeks-old (ENVIGO, France) were transplanted subcutaneously with approximately 20 mm3 tumor fragments under anesthesia (Ketamine/Xylazine). N = 7–10 mice with established tumors (62–196 mm3) were randomized from 10 to 13 mice/group. Tumor sizes were measured with calipers and their volumes calculated using L×W^2/2. Mice were treated on the same or following day after randomization. M3541 and M4076 were suspended in vehicle of 0.5% Methocel K4M, 0.25% Tween20, 300 mmol/L sodium citrate buffer pH 3.2 (M3541), or water (M4076). Niraparib and Rucaparib were applied in 0.5% Methylcellulose (Sigma M0430)/water and Cisplatin in 0.9% saline. IR was administered locally by positioning the tumor-bearing area under the beam while shielding the rest of the body with a lead shield. Mice were anesthetized and irradiated in groups of 9 or 10 with 2 Gy/fraction using the X-RAD320 cabinet (Precision X-ray Inc.) set to 10 mA, 250 kV, 58 s, 50 cm FSD collimator, 2 mm A1 filter.

For PD studies, mice with established FaDu xenografts were treated with a single dose of M3541 or M4076 and 2 Gy IR. Animals were sacrificed and compound concentrations in the blood were determined by HPLC-MS/MS. Tumors were removed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, lysed in HGNT buffer (100 μL/10 mg tissue), homogenized by Precellys-24 homogenizer, and centrifuged. pATM and pCHK2 levels were determined in the supernatant by the Luminex technology as described previously in detail in Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were done with GraphPad Prism Software, version 8.0. Experimental data were analyzed with Student t test unless indicated otherwise. Tumor volume data are presented graphically as mean ± SEM by symbols or as individual mice by lines. Other statistical methods are described previously in the figure legends. Statistically significant differences are labeled with *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; and ****, P < 0.0001.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Results

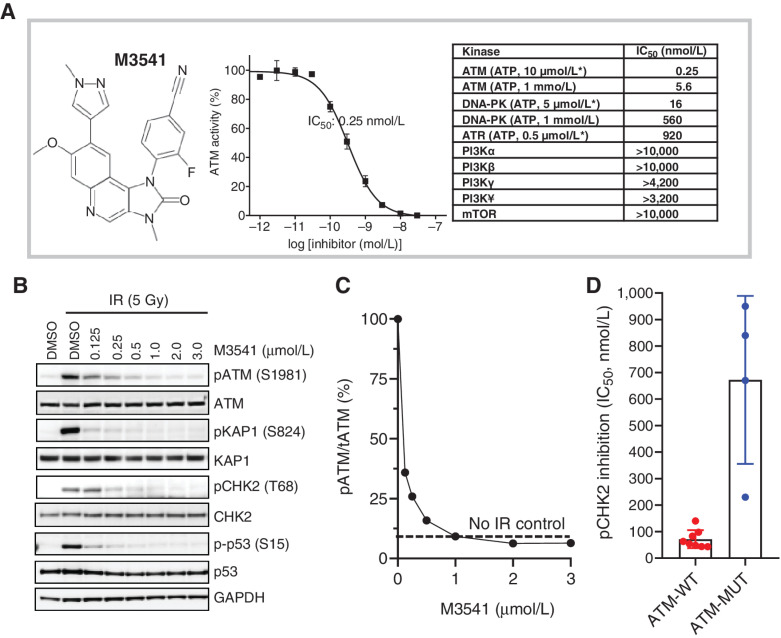

M3541 is a potent and selective inhibitor of ATM kinase activity

M3541 is a representative of a new class of reversible 1,3-dihydro-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-2-one inhibitors of ATM kinase (Fig. 1A). In cell-free assays, it inhibited ATM activity with an IC50 value of 0.25 nmol/L at the Km for ATP (10 μmol/L; Fig. 1A). The potency was reduced approximately 22-fold in the presence of high ATP concentration (1 mmol/L), indicating an ATP-competitive binding mode (Fig. 1A). M3541 showed a good margin of selectivity against the closely related PIKK family members with DNA-PK inhibited at 60-fold higher concentration at their Km for ATP whereas other members (PI3K isoforms, mTOR, and ATR) were unaffected (Fig. 1A). Selectivity profiling with a panel of 292 protein kinases identified only four additional kinases (ARK5, FMS, FMSY969C, and CLK2) inhibited over 50% by M3541 at 1 μmol/L concentration (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

M3541 is a potent and selective inhibitor of ATM kinase activity. A, M3541 structural formula, concentration–response relationship in in vitro ATM kinase assays and summary of potency and selectivity. The IC50 value data for ATM kinase and closely related members of PI3K-related kinases is listed. Kinase assays with ATP concentrations at or near KM are labeled (*). B, M3541 inhibits ATM signaling. A549 cells were pre-treated with increasing concentrations of M3541 for 1 hour and exposed to IR (5 Gy). Whole-cell lysates were collected 1 hour after IR and p-ATM and its downstream targets pKAP1, pCHK2 and pp53 were analyzed by Western blotting. C, pATM levels from western blot images (B) at different M3541 concentrations were quantified by GE Imager using ImageJ software and plotted as the percentage of the IR-induced p-ATM (100%). Dotted line represents uninduced p-ATM level. D, Inhibition of ATM signaling by M3541 in a panel of ATM wild-type (A375, A549, FaDu, HCC1187, HT29, MCF-7, NCI-H460, and SW620) and ATM mutant cancer cell lines (Granta-519, HT-144, NCI-H1395, and NCI-H23). Cells were treated with increasing M3541 concentrations in the presence of the radiomimetic bleomycin (10 μmol/L) for 3–6 hrs. P-CHK2 (Thr68) was measured by ELISA in whole-cell lysates and IC50 values calculated.

In cultured cancer cells, the inhibitory activity of M3541 was monitored by the level of ATM autophosphorylation at Ser1981 or the phosphorylation of its downstream targets, KAP1 (Ser824), CHK2 (Thr68), and p53 (Ser15). DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation (5 Gy) led to a robust activation of the ATM pathway in proliferating A549 cells as followed by Western blot analyses (Fig. 1B). M3541 inhibited the phosphorylation of ATM as well as its cellular substrates CHK2, KAP1, and p53 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Quantification of the protein levels showed that 1 μmol/L or higher M3541 concentrations completely suppressed radiotherapy-induced ATM phosphorylation in A549 cells (Fig. 1C). ATR-dependent CHK1 phosphorylation in HT29 cells and DNA-PK autophosphorylation in HCT116 cells was not affected by M3541, nor was PI3K pathway activity measured by pAKT levels in PC3 cells (Supplementary Table S3).

The inhibitory activity of M3541 was assessed in several additional cancer cell lines, including lines with mutations in the ATM gene producing functionally impaired ATM (Granta-519, HT-144, NCI-H1395, NCI-H23; refs. 25–27). CHK2 phosphorylation induced by the radiomimetic drug bleomycin was measured in eight other cancer cell lines with wild-type ATM (Fig. 1D, mean IC50, 71 nmol/L; range, 43–140 nmol/L) whereas significantly reduced in the four tested cancer cell lines expressing mutated ATM (mean IC50, 670 nmol/L; range, 230–950 nmol/L). These results indicated that M3541 requires wild-type ATM kinase and functional signaling for its inhibitory activity.

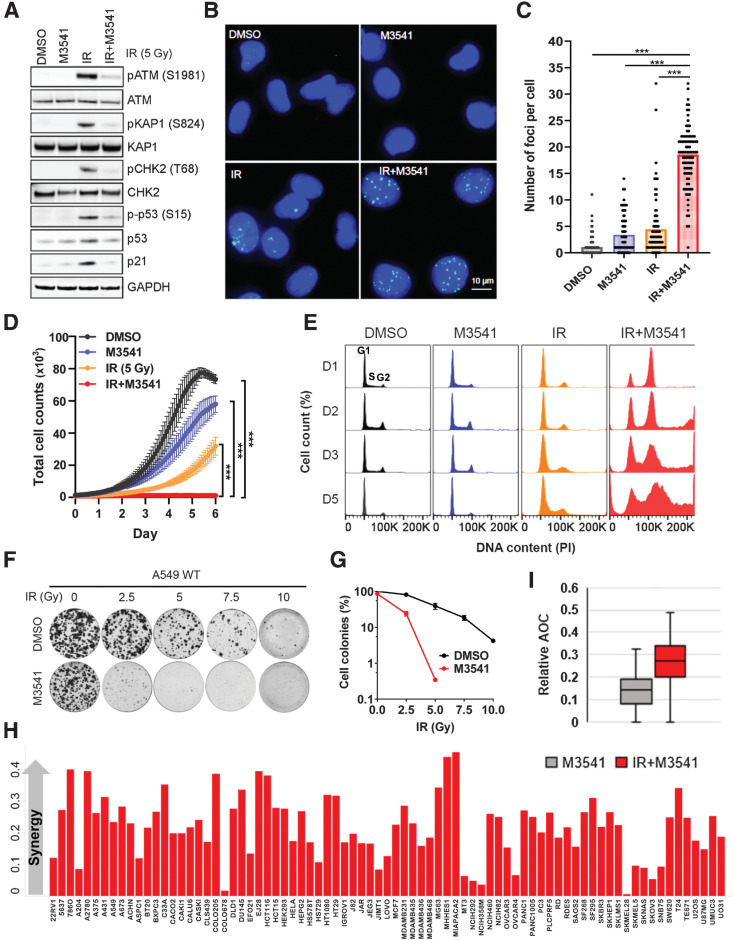

M3541 inhibits DSB repair and sensitizes cancer cells to radiotherapy

We investigated the cellular consequences of ATM inhibition by M3541 by assessing the effect on IR-induced DNA DSB formation, cell growth, cell-cycle progression, and clonogenic cancer cell growth. A fixed 1 μmol/L M3541 concentration was chosen for these studies because it effectively inhibits IR-induced ATM signaling (>90%) while retaining selectivity against other kinases (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Table S3). A 5Gy IR dose strongly enhanced ATM autophosphorylation and the levels of pKAP1, pCHK2, p53 as well as its downstream transcriptional target p21, indicating functional ATM pathway response in the A549 cells. Exposure to 1 μmol/L M3541 showed an effective suppression of radiotherapy-induced ATM-dependent pathway response (Fig. 2A). To assess the effect of M3541 on DSB repair, the number of γH2AX foci in irradiated A549 cells was quantified (Fig. 2B and andC).C). Exposure to IR (5Gy) led to a notable increase in foci number 24 hours after irradiation compared with vehicle. Co-treatment with M3541 showed a substantial increase in the γH2AX fraction, indicating that M3541 significantly impaired DSB repair, leading to accumulation of unrepaired DSBs (Fig. 2C). Only a minor increase in foci number was observed in unirradiated cells treated with the inhibitor alone. Taken together, these data suggest that treatment of A549 cells with M3541 inhibited IR-induced ATM catalytic activity, downstream signaling and DSB repair, resulting in a substantially increased fraction of cancer cells carrying potentially lethal DNA lesions.

M3541 selectively inhibits DSB repair and sensitizes cancer cells to radiotherapy. A, M3541 suppresses IR-induced ATM signaling. A549 cells were pre-treated with 1 μmol/L M3541 before 5Gy IR. After 6 hours, whole-cell lysates were prepared, and ATM and ATM pathway targets were assessed by Western blotting. B, M3541 inhibits repair of IR-induced DSBs. A549 cells were treated as described previously in (A) and γH2AX foci were detected by immunofluorescence 24 hours after IR. Representative images are shown at ×20 magnifications. γH2AX foci in green and nuclear staining by DAPI shown in blue. C, Quantification of γH2AX foci shown in B using ImageJ software. D, M3541 inhibits the growth of A549 cells. Growth/viability curves of A549 Nuclight cells treated as in (A) were generated by IncuCyte live cell imaging (images taken every 2 hours for 6 days). The number of green-fluorescent nuclei represents the total number of cells (mean ± SEM). E, In combination with IR, M3541 disrupts cell-cycle progression. Cell-cycle profiles of A549 cells treated with DMSO, M3541, IR or IR+M3541 at different time points. F, M3541 inhibits clonogenic cell growth. A549 cells challenged with different doses of IR plus/minus 1 μmol/L M3541 were incubated at 37°C for 14 days. Cell colonies were visualized by staining with 0.5% crystal violet, imaged and quantified. G, Colony growth relative to DMSO controls shown in (F) was quantified and plotted as a function of IR dose. H, Cell growth/viability of 79 cancer cell lines in response to M3541 alone or in combination with IR (3Gy) was quantified by sulforhodamine B (SRB) straining. Synergy score was calculated by the Bliss excess method as described previously in Materials and Methods and cell lines were plotted in alphabetical order. I, Box plot representation of synergy scores calculated for IR alone and IR + M3541 groups.

Next, we examined the effect of the combined treatment on cancer cell growth. A549 NucLight cells were exposed to IR (5Gy), M3541 (1 μmol/L) or a combination of both and monitored by live imaging over a period of 6 days (Fig. 2D). These cells express nuclear GFP allowing easier visualization and accurate counting of live cells. M3541 treatment alone showed a slight growth retardation, IR significantly slowed growth but IR+M3541 combination halted cell growth during the 6-day observation period. The cell-cycle analyses of exponentially proliferating A549 cells exposed to IR alone showed a reduction in the S-phase population 24 hours after IR due to arrest in G1 and G2–M. Effective DSB repair allowed most cells to resume proliferation within 48 hours (Fig. 2E). IR+M3541 combination induced a predominant G2–M phase arrest. In the next two days, cell-cycle profile showed increased sub-G1 and polyploid populations, suggesting that cells are undergoing aberrant mitotic transition, which may lead to death. The cell-cycle profile at day 5 reflected a mix of cells with increasing ploidy as well as cells undergoing cell death.

Then, we tested the effect of M3541 in combination with IR on the clonogenic growth of A549 cells. The colony forming potential of A549 was only slightly changed at a dose of 2.5 Gy but notably affected by 5 Gy and higher doses. However, it was strongly reduced after addition of 1 μmol/L M3541 to all IR doses compared with IR alone (Fig. 2F and andG).G). Additional 13 cancer cell lines of diverse tumor origin were tested for M3541 sensitivity in combination with IR and showed substantially reduced colony formation in a concentration-dependent manner regardless of tumor type (Supplementary Table S4).

Radiosensitization screen in a panel of 79 cancer cell lines revealed a broad combination effect of IR and M3541 (Fig. 2H–I). In this study, cancer cell viability was determined after exposure to 3 Gy IR in the presence or absence of M3541 for 120 hours and cell growth/viability was measured by sulforhodamine B staining (21). This combination effect was classified as synergistic in all cell lines in the panel, again, independent of the tumor origin or TP53 mutation status of the tested cell lines (Supplementary Table S5).

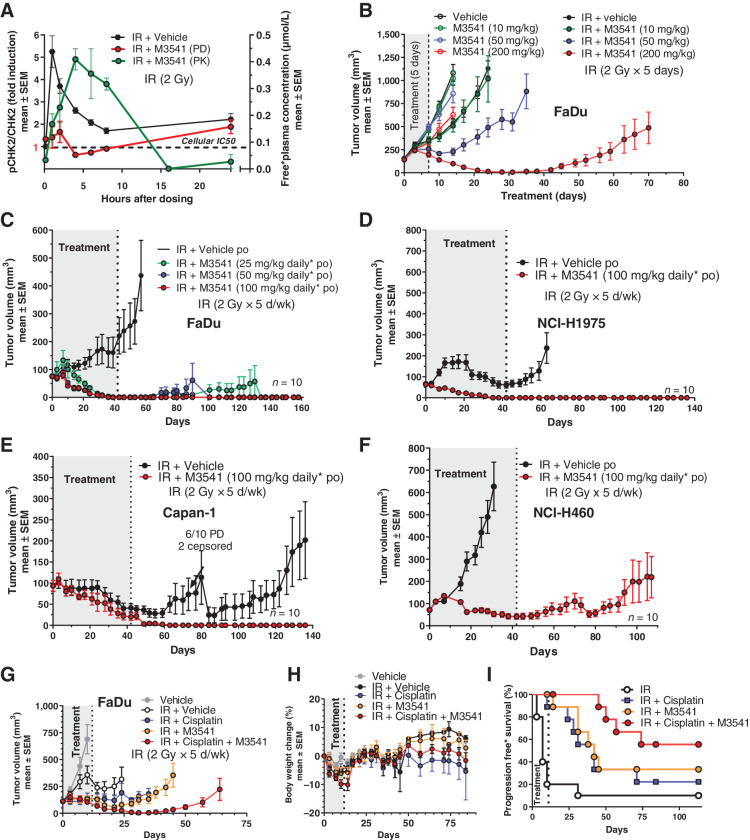

M3541 suppresses ATM pathway activity and potentiates radiotherapy efficacy in xenograft models of human cancer

Radiotherapy-induced ATM signaling pathway involves the direct phosphorylation of CHK2 on threonine 68. We hypothesized that phospho-CHK2 (Thr68) levels correlate well with inhibition of ATM and could thus serve as a pharmacodynamic (PD) biomarker. Mice with established FaDu xenografts were given M3541 (10 minutes before 2Gy IR) and pCHK2 (Thr68) was measured in tumor tissue (PD) at several time points. CHK2 phosphorylation increased quickly peaking at 1 hour after IR and returning close to baseline over the course of the 24 hours observation period (Fig. 3A). Co-administration of IR and M3541 (100 mg/kg) inhibited CHK2 phosphorylation with strongest effects corresponding to the highest plasma concentration of M3541. These data demonstrated exposure-dependent inhibition of IR-induced CHK2 phosphorylation by M3541 in vivo. Inhibition of ATM signaling translated into dose-dependent tumor growth inhibition of FaDu xenografts by M3541 (10, 50, or 200 mg/kg) in combination with fractionated radiotherapy (2 Gy IR fractions given days 1–5, total dose 10 Gy; Fig. 3B). ATM inhibitor was administered only for the duration of radiotherapy treatment, yet the tumors in the highest dose group continued to regress reaching complete regression on day 30. However, in this setting the combination benefits lasted only for a period of time and most tumors re-grew by the end of the observation period (Day 70).

M3541 potentiates IR efficacy in xenograft models of human cancer. A, M3541 inhibits ATM downstream phosphorylation target p-CHK2 in vivo. pCHK2 (Thr68) modulation was measured in response to IR (black) or combination with IR + M3541 (red). FaDu xenograft bearing mice (5 mice per treatment and timepoint) received a single treatment of 2 Gy IR with or without 100 mg/kg M3541. M3541 was given orally 10 minutes before IR. pCHK2 modulation was measured in tumor lysates at indicated timepoints. Plasma concentrations of M3541 were determined and plotted (green). B, M3541 dose dependently enhances IR effect in FaDu xenografts. Tumor-bearing mice (10 mice per arm) were treated with M3541, IR (2Gy x 5 days; total dose: 10 Gy) or IR + M3541 and tumor volume was followed for a maximum of 70 days. C–F, M3541 strongly enhances IR efficacy in 6-week fractional radiotherapy studies with 4 xenograft models. Mice (10 mice per arm) were irradiated with 2Gy fractions (5 days on, 2 days off) for 6 weeks. M3541 was given orally 10 minutes before IR at the indicated doses. Tumor growth was followed for at least 9 weeks after treatment. G–I, M3541 demonstrated combination benefit with the SoC regiment IR + cisplatin in the FaDu model. Mice with established xenografts (10 mice per arm) received 2 Gy IR fractions (5 days on/2 days off) for 2 weeks (20Gy total dose). Cisplatin was given intraperitoneally at 3 mg/kg on days 0 and 7 and M3541 at 100 mg/kg 10 minutes before each radiotherapy fraction. G and H, Tumor volume and body weight changes. I, Progression-free survival. Tumors with relative tumor volume change values ≤73% were categorized as an event. This cutoff value was selected in accordance with the RECIST definition for progressive disease based on tumor volume (44).

In clinical practice of radiotherapy, a total dose of 60 Gy, given in 30 fractions of 2 Gy over 6 weeks, represents a widely used regimen for cancer treatment with curative intent (28, 29). Therefore, we investigated the potential of M3541 as a combination partner of the well-established standard-of-care (SoC) radiotherapy in four xenograft mouse models representing different cancer indications, FaDu (head and neck), NCI-H1975 (lung), Capan-1 (colorectal), and NCI-H460 (lung; Fig. 33CC–F). In all models, M3541 strongly enhanced IR demonstrating complete and durable tumor regressions in 3 out of 4 models (Fig. 33CC–E). FaDu, NCI-H1975 and Capan-1 tumors completely regressed during or shortly after the combination treatment with the high M3541 dose (100 mg/kg) and did not re-grow for the duration of each study (140–160 days). The NCI-H460 model was rapidly progressing under IR treatment, indicating insensitivity to radiotherapy (Fig. 3F). When treated in combination with ATM inhibitor, tumors of this IR-resistant model only partially regressed during the treatment period. In all studies, the treatment was generally well-tolerated. During the treatment period, the animals in all treatment groups showed moderate body weight loss, likely due to the daily treatment procedures (i.e., multiple oral gavages, anesthesia, and radiotherapy treatment over a period of 6 weeks; Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2).

Cisplatin is a DNA-damaging agent that is commonly used as a radiosensitizer. Its primary antitumor mechanism does not involve generation of DNA DSBs or inhibition of specific components of the DSB DDR; moreover, it is not synergistic with ATM inhibition in vitro, as shown below. We hypothesized that based on the mechanistic differences in radiosensitization, the addition of an ATM inhibitor to IR/cisplatin may still enhance the antitumor effect in vivo. The triple combination of IR, cisplatin and M3541 was investigated in the FaDu xenograft model. Mice received 2 Gy radiotherapy fractions (5 days on/2 days off) for 2 weeks (20 Gy total dose). Cisplatin was given intraperitoneally at 3 mg/kg on days 0 and 7 and M3541 at 100 mg/kg 10 minutes before each IR fraction. Cisplatin and M3541 showed similar enhancement of antitumor activity together with IR (Fig. 3G). The triple combination demonstrated yet stronger antitumor activity as well as progression-free survival (Fig. 3I) with limited effect on the body weight within this treatment group (Fig. 3H). Remarkably, the body weight returned to the weight of vehicle-treated mice after treatment stop.

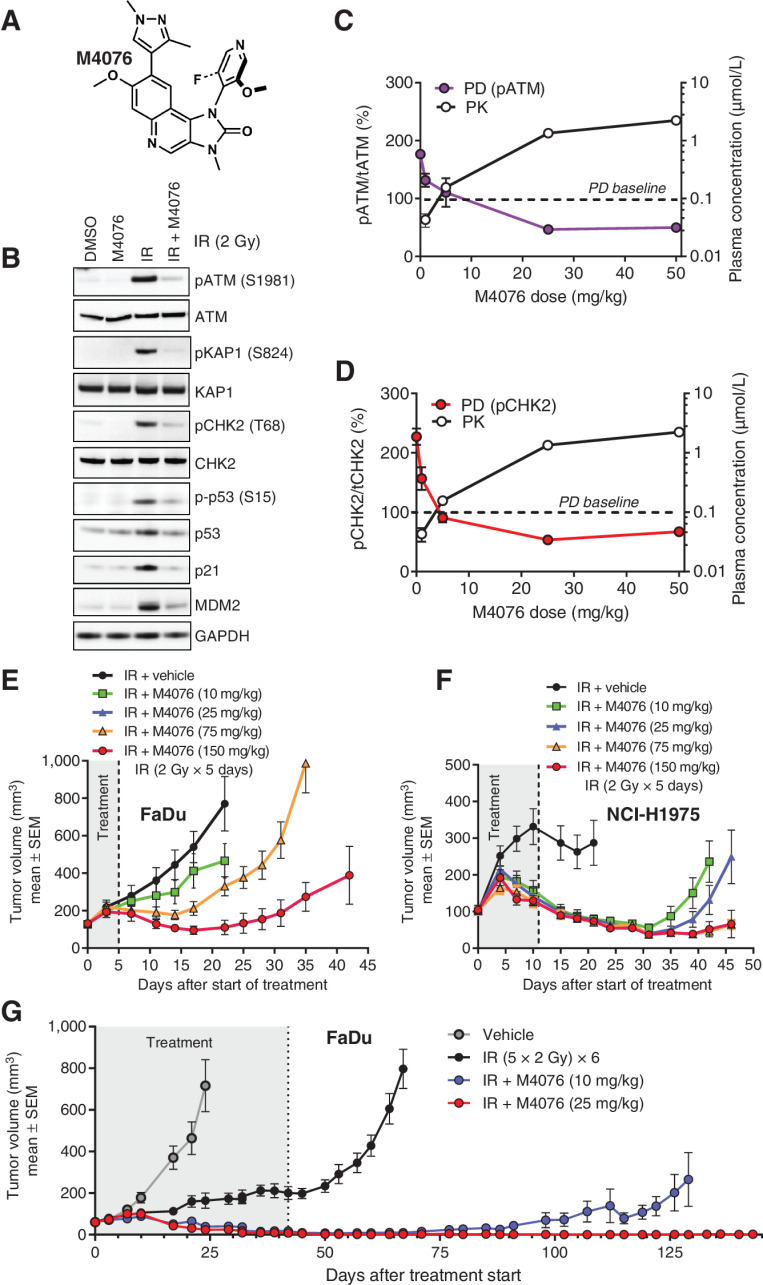

M4076 is an ATM inhibitor with superior pharmacological properties

M4076 (Fig. 4A) is an ATM inhibitor with substantially improved aqueous solubility at neutral pH and overall pharmacological properties (30). It displayed sub-nanomolar activity (0.2 nmol/L) at ATP concentrations near ATM Km and only a small drop in potency at 1 mmol/L ATP (0.7 nmol/L; ref. 30). To examine ATM selectivity at the cellular level, the effect of M4076 on members of the PI3K-related kinase pathways was assessed. Either ATR-CHK1 signaling in HT29 and DNA-PK activation in HCT116 was not affected by M4076 up to a concentration of 30 μmol/L. Phosphorylation of AKT in PC3 cells that is driven by PI3K lipid kinase activation through loss-of-function of the lipid phosphatase PTEN was only weakly affected with IC50 value of 9 μmol/L (Supplementary Table S6). Across a panel of eight cancer cell lines the cellular potency (IC50) for inhibition of ATM or CHK2 phosphorylation ranged between 9 and 64 nmol/L (Supplementary Table S7). M4076 effectively suppressed radiotherapy-induced ATM signaling indicated by inhibition of autophosphorylation as well as key downstream events such as phosphorylation and activation of KAP1, CHK2 and p53 as well as upregulation of p21 and MDM2 (Fig. 4B). Its cellular activity measured by inhibition of IR-induced ATM phosphorylation in A549 cells under the same experimental conditions used for M3541 (Fig. 1B and andC),C), was nearly identical in accordance with their similar cell-free potency (Supplementary Fig. S3).

M4076 is a superior ATM inhibitor with improved pharmacological properties. A M4076 structural formula. B, M4076 inhibits IR-induced ATM signaling in A549 cells. Cells were exposed to 1 μmol/L M4076 an hour before irradiation (5Gy), cell lysates were prepared 6 hours later and ATM signaling assessed by Western blotting. C and D, M4076 inhibits ATM direct phosphorylation targets, p-ATM and p-CHK2, in vivo. The levels of p-ATM (purple) and p-CHK2 (red) were measured in response to IR alone or IR + M4076 in the FaDu model. Mice bearing established xenografts (5 mice per treatment and dose) received 2 Gy IR with or without indicated doses of M4076 given orally 30 minutes before IR and tumor lysates were prepared 2 hours after M4076 administration. Plasma concentrations of M4076 were determined in parallel and plotted (black). Baseline levels of p-ATM and p-CHK2 are represented by the dotted horizontal lines. E, M4076 enhances IR effect in FaDu xenografts. FaDu tumor-bearing mice (9 mice per arm) were treated with IR (2Gy fraction x 5 consecutive days; total IR dose 10 Gy) or IR + M4076 at the indicated doses and tumor growth and body weight of mice was followed for 42 days. F, M4076 enhances IR efficacy in the NCI-H1975 xenograft model. Mice with established xenografts (9 per arm) were treated as in (E) for 2 weeks (total IR dose 20 Gy). Tumor growth and body weight was followed for 46 days. G, M4076 strongly enhances IR efficacy in the 6-week FaDu xenograft model. Mice (10 mice per arm) were treated with IR or IR + M4076 as in (E) but for 6 consecutive weeks (total IR dose 60 Gy) simulating a curative treatment regimen. Tumor growth and body weight was followed for 143 days.

Extensive in vitro evaluation indicated that M4076 can enhance radiotherapy sensitivity in a diverse set of cancer cell lines. Colony formation assays were performed to assess the effects of M4076 on clonogenicity in combination with IR. M4076 enhanced IR-induced suppression of colony formation in combination with IR in multiple cancer cell lines of diverse tumor origins (head and neck, colon, lung, gastric, breast, and melanoma) in a potent and dose-dependent manner (Supplementary Table S8).

M4076 demonstrated exposure-dependent suppression of ATM activity in the FaDu xenograft model, measured by the levels of IR-induced ATM and CHK2 phosphorylation (Fig. 4C and andD).D). Radiotherapy potentiation effects of M4076 were then investigated in xenograft mouse models. When combined in different settings of fractionated radiotherapy, either 5 × 2 Gy in the FaDu xenograft model (Fig. 4E) or 10×2 Gy fractions in the NCI-H1975 model (Fig. 4F), M4076 showed strong dose-dependent sensitization. Using the 6-week (30×2 Gy) fractionated treatment in FaDu xenografts, complete tumor regression was noted in the 25 mg/kg dose group and mice were considered cured for the duration of the observation period (130 days; Fig. 4G). Again, the moderate body weight loss observed during the treatment period was completely reversible (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5).

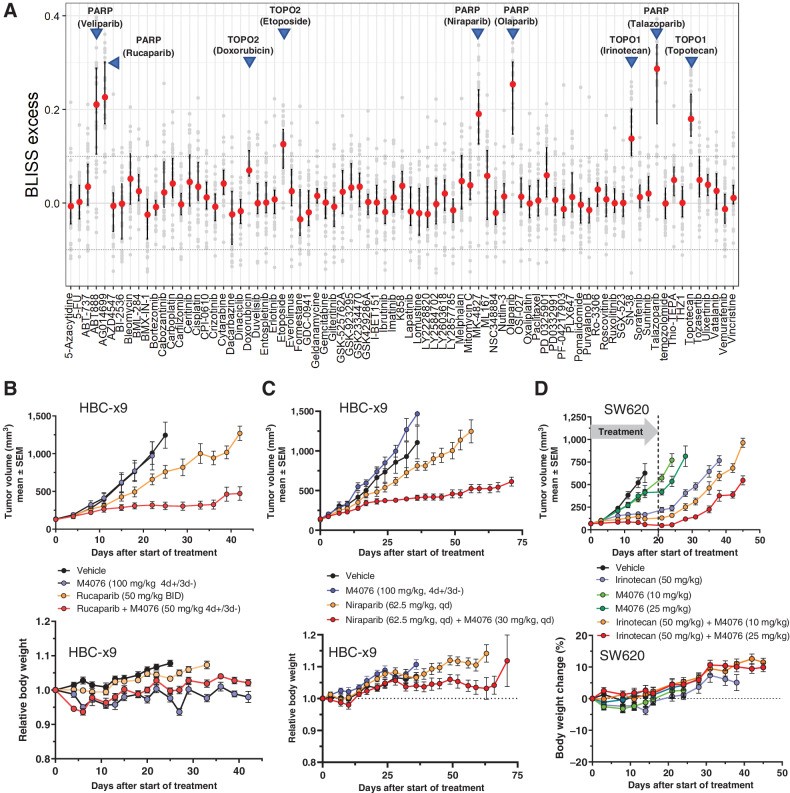

M4076 synergizes with topoisomerase and PARP inhibitors

In search of further synergistic combination partners, we tested M4076 in pairwise combinations with 79 established and research level anticancer agents in a subset of 34 randomly selected cancer cell lines. M4076 was strongly synergistic (Median bliss excess >0.1) with all five tested PARP inhibitors (talazoparib, rucaparib, niraparib, veliparib or olaparib) as well as the two tested topoisomerase I inhibitors (irinotecan and topotecan; Fig. 5A). A strong and broad synergistic combination effect with topoisomerase II inhibitors was observed for etoposide but less pronounced for doxorubicin. The remainder of the tested compounds has shown heterogeneity of response with weak to moderate combination effects across the tested cancer cell lines.

M4076 synergizes with topoisomerase and PARP inhibitors. A, Pairwise combination synergy analysis of 79 anticancer agents combined with M4076 in a panel of 34 cancer cell lines. Small-molecule agents representing diverse modes of action were combined with M4076 in a subset of cancer cell lines and evaluated for growth/viability after incubation for five days. Bliss excess was calculated per drug and cell line. Drug combination effects across the cell line panel were plotted using the median, 25th and 75th percentile connected by line to visualize combination effects across the cell line panel. Horizontal lines at Bliss excess of 0.1 and −0.1 serve as threshold for weak/moderate and strong combination synergy effects. B–C, Combination effect of M4076 with rucaparib (B) or niraparib (C) in the HCB-x9 breast cancer model. Efficacy and body weight changes in HBCx-9 TNBC PDX–bearing mice (9 mice per arm for B; 7 mice per arm for C) receiving orally M4076 plus either of the two PARP inhibitors were monitored for 45 (rucaparib) or 75 (niraparib) days. D, Efficacy and body weight changes of M4076 in combination with irinotecan in the SW620 xenograft model. Mice (10 per arm) were treated with 3×1-week cycles of the combination or respective monotherapy control arms. One cycle consisted of a single irinotecan application (intraperitoneally) at a dose of 50 mg/kg, followed by 10, and 25 mg/kg of M4076 (po) 24 hours later and for four subsequent days.

Out of 79 cancer drugs, representing all major anticancer mechanisms, PARP inhibitors were identified as the most synergistic combination partners of M4076. The in vitro screen revealed broad combination potential for M4076 and PARP inhibitors, independent of BRCA mutation status. We tested the combination efficacy of M4076 and two clinically approved PARP inhibitors, rucaparib and niraparib in a BRCA wild-type PDX model of triple negative breast cancer (HBC-x9). In this model, M4076 alone did not show significant antitumor effect whereas both PARP inhibitors had a slight growth inhibitory activity. The combination of M4076 with both rucaparib and niraparib demonstrated a marked combination benefit (Fig. 5B and andC,C, top). Next, we tested the antitumor efficacy of M4076 in combination with irinotecan in vivo. Mice bearing human colorectal xenografts (SW620) were treated with three weekly cycles of a combination of irinotecan and M4076, or the respective monotherapy control arms. One cycle consisted of a single irinotecan application (intraperitoneally) at a dose of 50 mg/kg, followed by 10, 25, and 50 mg/kg of M4076 (po) administered the next four following days. ATM inhibitor at 25 mg/kg demonstrated a pronounced combination benefit that persisted 25 days after treatment end (Fig. 5D, top). The combination treatment was well tolerated with minimal weight loss observed (Fig. 5B–D, bottom).

Discussion

The ATM pathway is a key regulatory node in the cellular response to DNA damage, driving both DSB repair and cell-cycle checkpoints to minimize the consequences of this most lethal form of DNA damage (1). Because of the elucidation of its important role, ATM kinase emerged as an attractive target for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Inactivation of ATM due to gene mutations or via molecular biology approaches has shown that ATM deficiency sensitizes cancer cells to ionizing radiation and DNA damaging chemotherapeutic agents (6). Several small-molecule compounds have been discovered and used as molecular probes to further refine ATM functions and assess their potential as therapeutic agents (10, 12). Despite their limited potency and selectivity those early inhibitors have helped to validate the hypothesis that temporary suppression of ATM activity could potentiate antitumor effect of radiotherapy and DSB-inducing therapeutic agents (11)

Here, we describe two highly potent and selective members of a new class of small-molecule ATM inhibitors, M3541 and M4076. Preclinical studies in vitro demonstrated that M3541 inhibits ATM activity at sub-nanomolar concentrations, effectively suppresses its downstream signaling and the repair of IR-induced DSBs. Persistence of unrepaired DSBs in cancer cells caused disruption of cell-cycle progression, aberrant mitotic division, polyploidy, and cell death in treated cancer cells. These findings are consistent with the known mechanistic consequences of entering mitosis with unrepaired DSBs (31). M3541 strongly enhanced the inhibitory effect of IR on cancer cell growth and colony formation. Although variable in magnitude this effect was universal and independent of tumor type, suggesting a wide applicability in combination with radiotherapy.

In vivo studies demonstrated a strong combination efficacy with fractionated radiotherapy in four mouse xenograft models. When applied to a clinically relevant, 6-week fractionated radiotherapy regimen, M3541 demonstrated an outstanding combination activity. In three of the xenograft models (FaDu, NCI-H1975, Capan-1) complete tumor regression was observed and maintained beyond treatment until the end of the observation period (130–160 days). Although full tumor regression was not achieved and xenografts regrew in the radiotherapy insensitive NCI-H460 model, M3541 still caused a strong enhancement of the radiotherapy response. No dermatitis or visible skin reaction was observed during the entire treatment and follow-up periods in any of the studies. This is in line with previous in vitro findings with early ATM inhibitors (11) and suggests that temporary suppression of ATM activity in combination with SoC radiotherapy may not lead to significantly enhanced normal tissue toxicity in the clinic. Under identical experimental conditions, the combination of fractionated radiotherapy with DNA-PK inhibitor peposertib (formally known as M3814) showed comparable enhancement of radiotherapy efficacy but also signs of enhanced skin toxicity, a reversible grade 2 dermatitis (19). Combination of M3541 with another SoC regimen (fractionated radiotherapy plus cisplatin) also demonstrated enhanced chemoradiotherapy effect and survival benefit in the FaDu model of head and neck cancer.

Advanced medicinal chemistry optimization efforts gave rise to M4076, a compound with substantially improved solubility in aqueous and biorelevant media and further increased target selectivity compared with M3541. A recently determined co-crystal structure of ATM kinase bound to M4076 provided an explanation for the binding mode and high selectivity of the inhibitor (20). Another recent report provides a plausible explanation for the increased solubility of M4076 (32). M4076 proved similarly effective in suppressing ATM activity in cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Its remarkable combination activity in the 6-week FaDu model led to complete tumor regressions in most animals for the duration of the study (130 days). This activity was achieved at a substantially reduced dose (25 mg/mL), establishing M4076 as a preferred ATM inhibitor for clinical investigations.

In search of potential new combination partners, we screened M4076 with a library of small-molecule compounds representing major antitumor mechanisms. By testing combination effects within a panel of 34 cancer cell lines of different tumor origin we intended to identify treatment combinations with broader synergistic activity independent of the genetic background. A clear synergistic increase observed for a broader fraction of cell lines was used as a key criterion for the selection of combination partners. All five PARP inhibitors in the collection demonstrated strong synergy when combined with M4076. This result was not unexpected because PARP inhibition impairs the repair of single strand DNA breaks that, if left unrepaired, are converted to DSBs during DNA replication. In addition, PARP-trapping activity can cause stalled replication forks and DNA breaks if they are not repaired properly (33). These DSBs must be repaired for cells to survive, and ATM plays a central role in their repair by HR (34). However, the nature of its function upstream and downstream of DSB induction needs further experimental clarification. We examined the combination potential of M4076 with two PARP inhibitors, rucaparib and niraparib, in the HBC-x9 triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) model that expresses wild-type BRCA1/2. The combination studies with both PARP inhibitors showed enhanced efficacy and good tolerability, supporting further exploration of this combination in BRCA wild-type TNBC, a segment poorly responding to PARP inhibitors alone (35).

Topoisomerase I inhibitors (irinotecan and topotecan) were identified as combination candidates with strong synergistic effect detected in many cancer lines. Topoisomerase II inhibitors (etoposide and doxorubicin) showed quantitatively lower but still synergistic activity. Topoisomerase inhibitors bind to the topoisomerase I or II enzymes that aid in DNA-unwinding during replication. The inhibition of these enzymes prevents re-ligation of the DNA strands and causes DSBs (36). The combination potential of M4076 with irinotecan was confirmed by a mouse efficacy study in the colorectal SW620 xenograft model. Combination synergy was also seen in a limited number of cell lines for other molecules in our drug collection, but these did not meet our selection criteria for further evaluation.

The two small-molecule ATM inhibitors, M3541 and M4076, showed promising activity and selectivity making them excellent molecular tools for further exploration of ATM's role in DDR signaling and validation of the ATM inhibitory concept for cancer therapy. AZD1390 is another recent example of an ATP-competitive ATM inhibitor with similar potency and selectivity currently undergoing clinical investigation (15). The deficiency in ATM function created by gene deletion/disruption has been shown to be synthetically lethal with BRCA1 mutations (37) or defects in the Fanconi anemia pathway (38). Mutations in the ATM gene are considered as predictive biomarkers for increased sensitivity to DDR inhibitors, for example, PARP and ATR inhibitors, and ongoing trials are assessing their clinical utility (39–42). Although homozygous deleterious mutations that abolish ATM function are relatively rare in human cancer (43), ATM inhibitors may be able to effectively induce transient synthetic lethality in cancer cells. Our experiments demonstrated strong enhancement in the antitumor activity of DDR targeted drugs, PARP and topoisomerase inhibitors. M4076 augmented the efficacy of rucaparib, niraparib and irinotecan at well-tolerated concentrations and clinically relevant regimens in the tested in vivo models. Our data support further clinical exploration of the ATM inhibitors in combination with the SoC-fractionated radiotherapy of local or locally advanced solid tumors. Our results also suggest that combination with PARP and topoisomerase I inhibitors in the treatment of solid tumors is a warranting clinical examination. M4076 has demonstrated superior pharmacological properties and is currently being evaluated in a Phase I clinical trial in patients with advanced solid tumors (NCT04882917).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure

Supplementary Figure

Supplementary Figure

Supplementary Figure

Supplementary Figure

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Brullé-Soumaré (XenTech SAS, Evry, France) for running the in vivo PDX studies and Florian Szardenings and Brian Elenbaas for their suggestions. This work was funded by the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany (CrossRef Funder ID: 10.13039/100009945).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked advertisement in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Notes

This article is featured in Highlights of This Issue, p. 857

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Molecular Cancer Therapeutics Online (http://mct.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors' Disclosures

A. Zimmermann reports personal fees from Merck Healthcare KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany outside the submitted work. F.T. Zenke reports personal fees from Merck KGaA outside the submitted work; and all authors report employment with Merck KGaA or its affiliate EMD Serono Research and Development Institute, Inc., Billerica, MA. Merck KGaA, respectively, its affiliates have certain rights in patents, respectively, patent applications pertaining to M3541 (WO2012028233) and M4076 (WO2020193660; both of which are mentioned in the publication), with authors T. Fuchss and F. Zenke being named inventors on those patent applications (TF: both, FZ: WO2012028233)." H. Dahmen reports other support from the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany outside the submitted work. U. Pehl reports personal fees and other support from Merck KGaA outside the submitted work. T. Fuchss reports personal fees from Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany outside the submitted work. L.T. Vassilev reports other support from EMD Serono, Inc. outside the submitted work; and reports employment with EMD Serono, Inc. whose compounds are in clinical development. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

Authors' Contributions

A. Zimmermann: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. F.T. Zenke: Conceptualization, resources, formal analysis, supervision, methodology, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing. L.-Y. Chiu: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft. H. Dahmen: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. U. Pehl: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, supervision, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. T. Fuchss: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, supervision, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–review and editing. T. Grombacher: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. B. Blume: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. L.T. Vassilev: Conceptualization, resources, supervision, investigation, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. A. Blaukat: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.mct-21-0934

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://aacrjournals.org/mct/article-pdf/21/6/859/3191726/859.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/129393935

Article citations

PROTAC-mediated conditional degradation of the WRN helicase as a potential strategy for selective killing of cancer cells with microsatellite instability.

Sci Rep, 14(1):20824, 06 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39242638 | PMCID: PMC11379953

Consensus, debate, and prospective on pancreatic cancer treatments.

J Hematol Oncol, 17(1):92, 10 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39390609 | PMCID: PMC11468220

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Telomere-related DNA damage response pathways in cancer therapy: prospective targets.

Front Pharmacol, 15:1379166, 07 Jun 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38910895 | PMCID: PMC11190371

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Tumor biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and targeted therapy.

Signal Transduct Target Ther, 9(1):132, 20 May 2024

Cited by: 18 articles | PMID: 38763973 | PMCID: PMC11102923

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Quantum-assisted fragment-based automated structure generator (QFASG) for small molecule design: an in vitro study.

Front Chem, 12:1382512, 03 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38633987 | PMCID: PMC11021760

Go to all (18) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

Clinical Trials

- (1 citation) ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT04882917

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Selective Inhibition of ATM-dependent Double-strand Break Repair and Checkpoint Control Synergistically Enhances the Efficacy of ATR Inhibitors.

Mol Cancer Ther, 22(7):859-872, 01 Jul 2023

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 37079339 | PMCID: PMC10320480

Phenotypic Analysis of ATM Protein Kinase in DNA Double-Strand Break Formation and Repair.

Methods Mol Biol, 1599:317-334, 01 Jan 2017

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 28477129

Regulation of ATM in DNA double strand break repair accounts for the radiosensitivity in human cells exposed to high linear energy transfer ionizing radiation.

Mutat Res, 670(1-2):15-23, 05 Jul 2009

Cited by: 25 articles | PMID: 19583974

ATM's Role in the Repair of DNA Double-Strand Breaks.

Genes (Basel), 12(9):1370, 31 Aug 2021

Cited by: 32 articles | PMID: 34573351 | PMCID: PMC8466060

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany (1)

Grant ID: 10.13039/100009945

1,*

1,*