What do you think?

Rate this book

196 pages, Paperback

First published May 14, 1925

But—but—why did she suddenly feel, for no reason that she could discover, desperately unhappy? As a person who has dropped some grain of pearl or diamond into the grass and parts the tall blades very carefully, this way and that, and searches here and there vainly, and at last spies it there at the roots, so she went through one thing and another; no, it was not Sally Seton saying that Richard would never be in the Cabinet because he had a second-class brain (it came back to her); no, she did not mind that; nor was it to do with Elizabeth either and Doris Kilman; those were facts. It was a feeling, some unpleasant feeling, earlier in the day perhaps; something that Peter had said, combined with some depression of her own, in her bedroom, taking off her hat; and what Richard had said had added to it, but what had he said? There were his roses. Her parties! That was it! Her parties! Both of them criticised her very unfairly, laughed at her very unjustly, for her parties. That was it! That was it!Besides shedding light on my own strange neurosis, I think this passage also reveals something interesting about Clarissa Dalloway. Why do Peter’s comments about her being the perfect hostess bother her so much? Mrs. Dalloway often claims to be fortunate to have married a man who allows her to be independent, and to be grateful to have avoided a catastrophic marriage to one who would have stifled her. But to me, these are just rationalizations for her decision to marry someone with whom she does not share the kind of intimacy that she might have otherwise had. In a way, her parties have taken the place of that intimacy, though it is an intimacy on her terms—she is able to enjoy the company of her high society friends while still keeping them at a comfortable enough distance to shield them from learning too much about her. When Peter gently mocks her parties, it annoys her because it invariably results in her having to reconcile the sacrifices she has made in exchange for her current lifestyle.

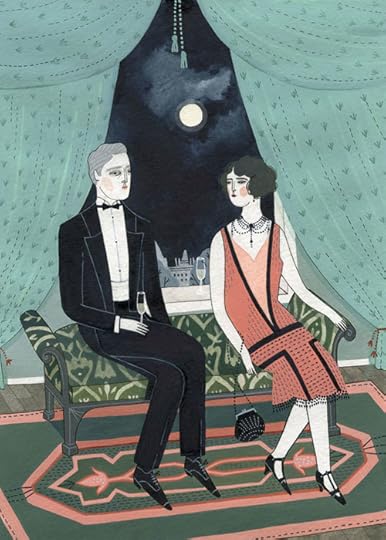

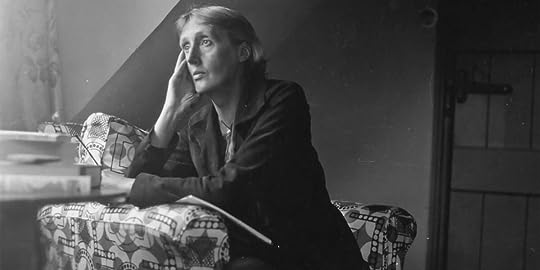

The strange thing, on looking back, was the purity, the integrity, of her feeling for Sally. It was not like one’s feeling for a man. It was completely disinterested, and besides, it had a quality which could only exist between women.Virginia Woolf’s own sexuality has been a topic of interest over the years, and the relationship between Clarissa and Sally—the kiss shared between them being considered by Clarissa to be a notable peak of happiness in her life—was often written as being “open to interpretation.” Which is funny to me because it feels like the tumblr joke of like “they were just really good friends,” and reading Woolf’s own letters with Vita Sackville-West it all feels very out in the open that there are queer desires in the novel that get packed away due to an unwelcoming society. We see how socially enforced gender norms and heterosexuality become restrictive and Sally is a symbol of rejecting those through examples such as her openly smoking cigars which is said to be a “man’s thing” to do. Through Clarissa we see a desire of life, of not becoming stagnant, of not ‘being herself invisible; unseen; unknown…this being Mrs. Dalloway; not even Clarissa any more; this being Mrs. Richard Dalloway.’ There must be a way to separate from the society, to form an identity beyond social conventions or gender, to find life in a world hurtling towards death.

So there was no excuse, nothing whatever the matter, except the sin for which human nature had condemned him to death; that he did not feel.While Clarissa grapples with her fear of death, ‘that is must end; and no one in the whole world would know how she had loved it all,’ Septimus finds life, a never-ending spiral of guilt for not feeling beset by visions of his fallen comrade, to be a fearsome and loathsome beast. Doctors would have him locked away (a dramatic contrast to the lively parties hosted by Clarissa), and even his own wife forges an identity of guilt and self-conscious sorrow for upholding a clearly disturbed husband. This is a haunting portrait of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, the latter fmuch like Woolf herself suffered. Septimus and Clarissa are like opposite sides to the same coin, however, and many essential parrallels exist between them. Both find solace in the works of Shakespeare², both obsess over a lonely figure in an opposing window (one of Septimus’ last impressions in the land of the living), and both trying to express themselves in the world yet fearing the solitude that their failures will form for them. Even his inability to feel is similar to the love felt by Clarissa: 'But nothing is so strange when one is in love (and what was this except being in love?) as the complete indifference of other people.'

Death was defiance. Death was an attempt to communicate; people feeling the impossibility of reaching the centre which, mystically, evaded them; closeness drew apart; repute faded, one was alone. There was an embrace in death.

For it was the middle of June. The War was over, except for some one like Mrs. Foxcroft at the Embassy last night eating her heart out because that nice boy was killed…but it was over; thank Heaven – over. It was June…and everywhere, thought it was still early, there was a beating, a stirring of galloping ponies, tapping of cricket bats…Cold death and warm life on a sunny June day all mingle together here, and throughout the novel. And we are constantly reminded of our lives marching towards death like a battalion of soldiers, each hour pounded away by the ringing of Big Ben. This motif is two-fold, both representing the lives passing from present to past, but also using the image of Big Ben as a symbol of British society. The war has ended and a new era is dawning, one where the obdurate and stuffy society of old has been shown to be withered and wilting, like Clarissa’s elderly aunt with the glass eye. Not only are the lifelines of each character put under examination, but the history of the English empire as well, highlighting the ages of imperialism that have spread the sons of England across the map and over bloody battlefields. Clarissa is a prime example of the Euro-centrism found in society, frequently confusing the Albanians and Armenians, and assuming that her love of England and her contributions to society must in some way benefit them. ‘But she loved her roses (didn’t that help the Armenians?)’ In contrast is Peter, constantly toying with his knife—a symbol of masculinity imposed by an ideal enforced by bloodshed and military might—to evince not only his fears of inadequacy as a Man (fostered by Clarissa’s rejection for him and his possibly shady marriage plans), but his wishy-washy feelings of imperialism after spending time in India.

Beauty, the world seemed to say. And as if to prove it (scientifically) wherever he looked at the houses, at the railings, at the antelopes stretching over the palings, beauty sprang instantly. To watch a leaf quivering in the rush of air was an exquisite joy. Up in the sky swallows swooping, swerving, flinging themselves in and out, round and round, yet always with perfect control as if elastics held them; and the flies rising and falling; and the sun spotting now this leaf, now that, in mockery, dazzling it with soft gold in pure good temper; and now again some chime (it might be a motor horn) tinkling divinely on the grass stalks—all of this, calm and reasonable as it was, made out of ordinary things as it was, was the truth now; beauty, that was the truth now. Beauty was everywhere.Mrs Dalloway is nearly overwhelming in scope despite the tiny package and seemingly singular advancements of plot. Seamlessly moving between the minds and hearts of each character with a prose that soars to the stratosphere, Woolf presents an intensely detailed portrait of post-war Europe and the struggles of identity found within us all. While it can be demanding at times, asking for your full cooperation and attention, but only because to miss a single second would be a tragic loss to the reader, this is one of the most impressive and inspiring novels I have ever read. Woolf manages to take the scale of Ulysses and the poetic prowess of the finest poets, and condense it all in 200pgs of pure literary excellence. Simple yet sprawling, this is one of the finest novels of the 20th century and an outstanding achievement that stands high even among Woolf's other literary giants. This novel has a bit more of a raw feel when compared to To the Lighthouse, yet that work is nothing short of pure perfection, a novel so highly tuned that one worries that even breathing on it will tarnish it's sleek and shiny luster. Dalloway stands just as tall, however, both as a satire on society and a powerful statement of feminism. A civilization is made up of the many lives within, and each life is made up of many moments, all of which culminating to a portrait of human beauty. Though at the end of life we must meet death, it is through death we find life.

For in marriage a little licence, a little independence there must be between people living together day in day out in the same house; which Richard gave her, and she him. (Where was he this morning, for instance? Some committee, she never asked what.) But with Peter everything had to be shared; everything gone into. And it was intolerable, and when it came to that scene in the little garden by the fountain, she had to break with him or they would have been destroyed, both of them ruined…

The world wavered and quivered and threatened to burst into flames. It is I who am blocking the way, he thought. Was he not being looked at and pointed at…

And it was an offering; to combine, to create; but to whom?

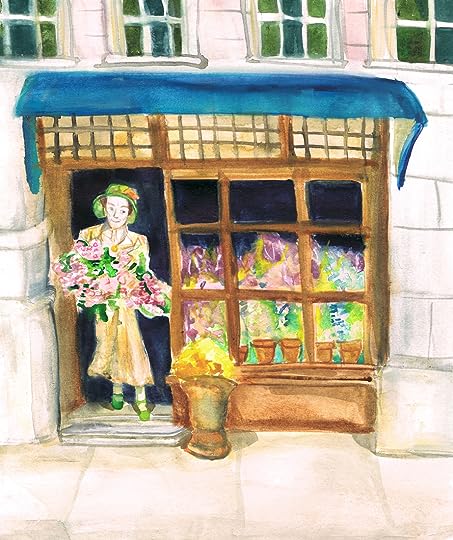

An offering for the sake of offering, perhaps. Anyhow, it was her gift. Nothing else had she of the slightest importance; could not think, write, even play the piano.