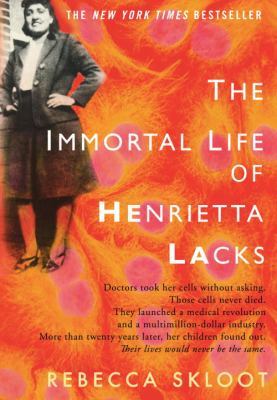

carol. 's Reviews > The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

by

by

Overall, a four star read that should probably be required reading for both biology and American history classes. (Actually, it was a far more interesting read than that makes it sound).

While I had heard a great deal of buzz on the book, I wasn't prepared for how the story evolved. The book alternates between Henrietta Lacks' personal history, that of her family, a little of medical history and Skoot's actual pursuit of the story, which helps develop the story in historical context. Skoots included a lot more science than I expected, and even with ten years in the medical field, I was horrified at times. Skoots does a decent job of maintaining a journalistic tone, but some of the things she relates are terrible, from the way Henrietta grew up to cervical cancer treatment in the 50s and 60s. These were the days before cancer treatments approached the precision medicine it is aiming for today, and the treatments resembled nothing so much as trying to cut fingernails with garden shears. Just the thought of a radioactive seed tucked in the uterus causing tissue burn was enough to give me sympathetic cramps.

Part of the evil in the book is the violence her family inflicted on each other, and it's one of the truly uncomfortable areas. I think that discomfort is important, because part of where this story comes from has to do with slavery and poverty. There isn't really an ethical high ground here, and that's part of Skoot's skill in setting up the story, and part of the problem in being a white woman telling the story of a black woman.

The only reason I didn't give this a five star rating is that the narrative started to fall apart at the end, leaving behind the stories of the cell line and focus more on the breakdown of Henrietta's daughter, Deborah. While I understand she is the touchstone for the story, that she is partly telling the story of the mother through the daughter, much of Henrietta and the science is sidelined.

Interesting questions popped up while reading; namely, why does everyone equate Henrietta's cancer cells with her person? As an illustration, if you tell people they have a cancerous tumor, the reaction is "get rid of it." It is categorized as "other" in everyone's mind and not recognized it as an intrinsic part of the person with cancer. It is not "them." Biologically speaking, I'm not sure the book answered the question of whether of not the HeLa cells actually were genetically identical to Henrietta, or if they were mutated--altered DNA. While that might be cold comfort, it's a huge philosophical and scientific question that is the pivot point for a number of issues. Treating the cells as if they were "normal" is part of what lead the scientists into disaster as evidenced by the discovery that so many cell lines were HeLa contaminated (I don't believe that transmission mechanism was explained either, which irks me). It also could be the basis for a sophisticated legal and ethical argument.

While I had heard a great deal of buzz on the book, I wasn't prepared for how the story evolved. The book alternates between Henrietta Lacks' personal history, that of her family, a little of medical history and Skoot's actual pursuit of the story, which helps develop the story in historical context. Skoots included a lot more science than I expected, and even with ten years in the medical field, I was horrified at times. Skoots does a decent job of maintaining a journalistic tone, but some of the things she relates are terrible, from the way Henrietta grew up to cervical cancer treatment in the 50s and 60s. These were the days before cancer treatments approached the precision medicine it is aiming for today, and the treatments resembled nothing so much as trying to cut fingernails with garden shears. Just the thought of a radioactive seed tucked in the uterus causing tissue burn was enough to give me sympathetic cramps.

Part of the evil in the book is the violence her family inflicted on each other, and it's one of the truly uncomfortable areas. I think that discomfort is important, because part of where this story comes from has to do with slavery and poverty. There isn't really an ethical high ground here, and that's part of Skoot's skill in setting up the story, and part of the problem in being a white woman telling the story of a black woman.

The only reason I didn't give this a five star rating is that the narrative started to fall apart at the end, leaving behind the stories of the cell line and focus more on the breakdown of Henrietta's daughter, Deborah. While I understand she is the touchstone for the story, that she is partly telling the story of the mother through the daughter, much of Henrietta and the science is sidelined.

Interesting questions popped up while reading; namely, why does everyone equate Henrietta's cancer cells with her person? As an illustration, if you tell people they have a cancerous tumor, the reaction is "get rid of it." It is categorized as "other" in everyone's mind and not recognized it as an intrinsic part of the person with cancer. It is not "them." Biologically speaking, I'm not sure the book answered the question of whether of not the HeLa cells actually were genetically identical to Henrietta, or if they were mutated--altered DNA. While that might be cold comfort, it's a huge philosophical and scientific question that is the pivot point for a number of issues. Treating the cells as if they were "normal" is part of what lead the scientists into disaster as evidenced by the discovery that so many cell lines were HeLa contaminated (I don't believe that transmission mechanism was explained either, which irks me). It also could be the basis for a sophisticated legal and ethical argument.

Sign into Goodreads to see if any of your friends have read

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

Sign In »

Reading Progress

Started Reading

November 1, 2010

–

Finished Reading

November 13, 2010

– Shelved

Comments Showing 1-20 of 20 (20 new)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Trudi--I'm sorry to hear about your mother. I think a great deal of the book is her daughter/family reacting to the idea that it's their mom being tested/sold/profited, etc. Except as a cancer nurses, most people think/say "get it out of me" even if it means taking the whole breast, radical surgery etc. It's 'foreign.' Its an interesting conception that came to me, especially after the author started to talk about the cell line contamination.

Trudi--I'm sorry to hear about your mother. I think a great deal of the book is her daughter/family reacting to the idea that it's their mom being tested/sold/profited, etc. Except as a cancer nurses, most people think/say "get it out of me" even if it means taking the whole breast, radical surgery etc. It's 'foreign.' Its an interesting conception that came to me, especially after the author started to talk about the cell line contamination.It's an interesting area--we don't normally think of 'waste' parts of us as 'us.' I've met very few women that want to save the placenta from birth, for instance, and I surely never asked for my appendix back. Those cells and body parts aren't 'me,'--I am far, far more than my DNA (which is why I think those people going after cloning their favorite dog is such a waste). Genetic arguments make me very nervous, because the transitions come fast and free: DNA = sex/race/sexuality = me = biological determinism.

I really like the questions and points you raise here. While I was reading, I kept thinking, but they're cancerous cells, they're not her, but I was also thinking, they came from her so there's a connection. Weird, huh? And I agree with your point about "get it out of me"; nobody wants to take a tumour home with them. At least, I don't think so.

I really like the questions and points you raise here. While I was reading, I kept thinking, but they're cancerous cells, they're not her, but I was also thinking, they came from her so there's a connection. Weird, huh? And I agree with your point about "get it out of me"; nobody wants to take a tumour home with them. At least, I don't think so.And I agree about the required reading comment. There are a lot of ethical and legal points brought up by this book that have got me thinking, and feeling like I have to start reading through Canada's Acts and regulations.....

Thanks, Lata. There's an interesting assumption about cells being a person (talk about reductionism!!) and, if I understand the journalist interpretation, these are technically cancerous (endless reproducing cells), as such, faulty cells that contributed to her death. Then again, there's the issue of disenfranchisement and the health care system, so even if they aren't her, surely there is some needed consent and disclosure. Such an interesting book for the topics it indirectly raises.

Thanks, Lata. There's an interesting assumption about cells being a person (talk about reductionism!!) and, if I understand the journalist interpretation, these are technically cancerous (endless reproducing cells), as such, faulty cells that contributed to her death. Then again, there's the issue of disenfranchisement and the health care system, so even if they aren't her, surely there is some needed consent and disclosure. Such an interesting book for the topics it indirectly raises.

I read this a few years ago and it opened to my eyes to things I didn't pay attention to. I remember being in a doctor's office and having to sign a release relinquishing all rights to any removed tissue. I remember thinking "Aha!! I know why this is required".

I read this a few years ago and it opened to my eyes to things I didn't pay attention to. I remember being in a doctor's office and having to sign a release relinquishing all rights to any removed tissue. I remember thinking "Aha!! I know why this is required".

Definitely a read on ethics. I thought that the cancer cells were less her and more 'HeLa' but still at a cost to her. From the horror of her medical treatment to the disregard of the expectation of her personal/private being. For that alone she (her family) should've received compensation. Which also brings up the idea that patients should be required to sign away their rights to any of their parts.

Definitely a read on ethics. I thought that the cancer cells were less her and more 'HeLa' but still at a cost to her. From the horror of her medical treatment to the disregard of the expectation of her personal/private being. For that alone she (her family) should've received compensation. Which also brings up the idea that patients should be required to sign away their rights to any of their parts.

A great review Carol. I too found this to be a very thought provoking and important book. A couple of comments.

A great review Carol. I too found this to be a very thought provoking and important book. A couple of comments.First, this book demonstrates how primitive much of our medical treatment was in the 50s and 60s. Cancer care consisted primarily of surgery, and other modalities, such as radiation, and later soon to follow chemotherapy, was really in its’ infancy. Much of what was done then, from the treatments to the supportive care, seems and really was pretty barbaric by our modern standards.

Second, this book also demonstrates how primitive the ethical guidelines about treatment were back then. Henrietta’s case, and many others in the 80s and 90s, helping the courts to legally define patients’ rights and helped to pave the way for our modern policies and concepts about medical consent. ANY tissue sampled from a living is now considered to be the property of that person, and the medical community is required to obtain consent for its’ use for research purposes.

Third, HeLa cells, and most cancer cells, are aberrant in that they will continue to grow without normal programmed death (the medical term is apoptosis). Cancer cells typically need a number of mutations in critical parts of their DNA to lose this control. Most of these mutations are acquired and present only in the cancer cell, what we call somatic, although some of them can be inherited (germline). These cells otherwise have the same DNA as the rest of the body, and are still in essence that persons’ own cells as much we might hate to embrace that idea.

Thanks for your comments, Edwin. You raise some interesting points. I didn't go into it in my review, but clearly, it was a time period when the entire concept of medical ethics was still in the dark ages, coupled with prejudices about competency in racial and economic groups. You make great points about ethical progress now and consenting.

Thanks for your comments, Edwin. You raise some interesting points. I didn't go into it in my review, but clearly, it was a time period when the entire concept of medical ethics was still in the dark ages, coupled with prejudices about competency in racial and economic groups. You make great points about ethical progress now and consenting.Funny, I thought I got into it in my review, but it must have been somewhere else--one of the most interesting things to come out of this read for me was a visceral understanding of why so many poor people of color seem to have a basic distrust of the medical system. The legacy of paternalism and 'benevolent' decision-making (ie. sterilization) coupled with flat-out wrongness like the Tuskegee syphilis experiments is an enormous emotional barrier that the medical system has only done the minimal in owning.

Thank you for your background on genetics and mutations. Granted, I didn't go into the cellular genetics of cancer, but really, when you look at the psychology of it, people don't think of cancer as 'self,' they think of it as 'other.' I can't tell you how many people say, "can't you just get it out of me?" so the concept that people want ownership over something that is considered both abhorrent and 'other' is an interesting dissonance. The fact that language surrounding it is posited as a "war on cancer," I think illustrates this nicely. This is not 'self' people are fighting; it is the 'enemy.'

In all practicality, cancer cells generally lack normal tissue functionality; ie. stem cell lines in the bone marrow aren't making functional red blood cells or platelets and are over-producing immature cells in leukemia. I know a bit about genetics as an oncology certified nurse, but my point was really both psychologically and practically, it's non functional and obstructive, otherwise it would be 'benign' or 'non-cancerous' tumors. Again, finessing the medicalese. :)

Oh my gosh, your mention of surgery and cancer treatments pre-1950s reminds me of the Malady of Cancer (? terrible with names today) and the author's recounting of the history of surgeries surrounding cancer. I didn't mention it with Henrietta either, but the implanted radioactive seeds in those days, so far from precision targeting now... Yikes. So. Horrifying. Burning from the inside out.

Oh my gosh, your mention of surgery and cancer treatments pre-1950s reminds me of the Malady of Cancer (? terrible with names today) and the author's recounting of the history of surgeries surrounding cancer. I didn't mention it with Henrietta either, but the implanted radioactive seeds in those days, so far from precision targeting now... Yikes. So. Horrifying. Burning from the inside out.

Great review! I particularly appreciate your views on this topic, being familiar with the medical field.

Great review! I particularly appreciate your views on this topic, being familiar with the medical field. Your point that how the HeLa cells are viewed might potentially form the basis for a sophisticated legal/ethical argument is particularly insightful: it's important that medical research not be impeded but to me the idea that Big Pharma/Big Med is making stacks of money from our bodies smacks of Corporate Slavery, for want of a better term. We may need to sign away rights to our body-bits these days, but as a patient my understanding is that if I want to be treated, I'd better sign the damn paper.

That Henrietta Lacks descended from actual American slaves makes the thought of the fortunes made from her (stolen) cells all the more repugnant. The idea that living in the "land of the free (market)" makes the concept of amassing enormous wealth from human suffering somehow OK is staining the American record as shamefully blood-red as the legal human slavery that preceded it. Our descendants will find us every ounce as appalling as we now view any Roman games-goer, assuming of course that our planet's little experiment in primate sentience survives itself & we have much more in the way of descendants.

Of course I am home sick, under-medicated & subjected to cable news ... probably not the best time to be posting! ;)

Such interesting comments! Athena--it is certainly an interesting topic, and now the trend is very much towards consents, perhaps even to the detriment of research. For instance, I recently heard about a controversy where an agency was using the leftover blood from required baby genetic screening (different states do different things, but WI screens for a disorder that can cause severe debility if the baby does not receive the right nutrition). I think an agency was then using the samples to collect information on a study, perhaps on what other disorders might not be identified? Anyway, despite it being sort of 'discarded,' the courts ruled that the agency had to get permission from parents to use the samples for any other non-official use.

Such interesting comments! Athena--it is certainly an interesting topic, and now the trend is very much towards consents, perhaps even to the detriment of research. For instance, I recently heard about a controversy where an agency was using the leftover blood from required baby genetic screening (different states do different things, but WI screens for a disorder that can cause severe debility if the baby does not receive the right nutrition). I think an agency was then using the samples to collect information on a study, perhaps on what other disorders might not be identified? Anyway, despite it being sort of 'discarded,' the courts ruled that the agency had to get permission from parents to use the samples for any other non-official use. The trouble is, people have such weird ideas of what science and genetics are, and I suspect it will only get worse with the fragmentation of the school system. So it's kind of a huge burden to explain to people with only the smallest grasp of science what exactly they are consenting to, and some people are generally suspicious of anything smacking of corporations and government. As mentioned above, sometimes justly so.

Hope you feel well soon, Athena. Fluids, fluids, and fluids. And turn off cable news--that'll only make you sicker.

Carol. wrote: "The trouble is, people have such weird ideas of what science and genetics are, and I suspect it will only get worse with the fragmentation of the school system"

Carol. wrote: "The trouble is, people have such weird ideas of what science and genetics are, and I suspect it will only get worse with the fragmentation of the school system"Well said! I suspect a lot of folks in your position have to deal with a shockingly uninformed/unwilling-to-be-informed, public, loading the burden of educating others onto medical staff who are trying to do their real jobs. You guys don't get paid enough!

I remember when I was in college, we had a unit on human biology, and you only took that if you were in a particular program. Otherwise, you didn't have to take it at all. I loved, loved, loved the course. I'm not joking. I really did. It was one of the few science courses that I really connected with (unlike all the physics courses I had to take, too, in college.) Plus, the teacher was dynamite, and was great at engaging all of us.

I remember when I was in college, we had a unit on human biology, and you only took that if you were in a particular program. Otherwise, you didn't have to take it at all. I loved, loved, loved the course. I'm not joking. I really did. It was one of the few science courses that I really connected with (unlike all the physics courses I had to take, too, in college.) Plus, the teacher was dynamite, and was great at engaging all of us.However, by the time my brother went to college, years later, curriculums had changed even further, and I think the interactive portions of biology classes had been diminished.

Sounds like an interesting class, Lata--too bad it was at the college level and not high school. Human biology-health just isn't covered enough at the advanced levels. I think mine in high school was half sex-education along with some general nutrition stuff.

Sounds like an interesting class, Lata--too bad it was at the college level and not high school. Human biology-health just isn't covered enough at the advanced levels. I think mine in high school was half sex-education along with some general nutrition stuff. I think it is more vital than--gasp--chemistry. We all, every one of us, have to manage our health. The actions of protons and electrons are all very interesting and perhaps necessary to advance education in sciences, and even to stretch the brain to the invisible world, but I'd rather have a better human biology unit.

Carol. wrote: "Sounds like an interesting class, Lata--too bad it was at the college level and not high school. Human biology-health just isn't covered enough at the advanced levels. I think mine in high school w..."

Carol. wrote: "Sounds like an interesting class, Lata--too bad it was at the college level and not high school. Human biology-health just isn't covered enough at the advanced levels. I think mine in high school w..."I suspect there might be some concern that teaching kids more about how their bodies function might discombobulate some parents, who prefer mysticism or lack of knowledge to a scientific approach.

The bio class we took in high school involved my lab partner mostly saying "Icky!" to a lot of things and me shushing him so I could hear the teacher. We didn't learn much in that class, as I remember, as the teacher spent most of his time just managing kids' behaviour.

As Skloot documents, the Lacks family has not received any compensation for the cells that were taken from Henrietta despite the incredible amount of money that organization's have made from their use of those cells. Now that is about to change.

As Skloot documents, the Lacks family has not received any compensation for the cells that were taken from Henrietta despite the incredible amount of money that organization's have made from their use of those cells. Now that is about to change. https://www.wsj.com/articles/henriett...

Wow, Carol, I hadn't even thought of that. It's a really good point. A lot of my emotional response to this book derived from losing my own mother to cervical cancer and wondering how I would react to discovering her cells were still out there growing unchecked by the billions. Would I still consider it her? How would it make me feel if like Henrietta's daughter, someone were to show me my mother's cells under a microscope growing and dividing?

My knee-jerk response is that it's still her, a part of her, something that started in her body, that contains her DNA. But maybe you're right. Cancer is so "alien", so destructive and quite often very separate from the body it is attacking... maybe there is so little left of the original host in those cells that to refer to them as that person is not only misleading, but grossly inaccurate.