Abstract

Free full text

Initial T cell frequency dictates memory CD8+ T cell lineage commitment

Abstract

Memory T cells can be divided into central memory T cell (TCM cell) and effector memory T cell (TEM cell) subsets based on homing characteristics and effector functions. Whether TEM and TCM cells represent interconnected or distinct lineages is unclear, although the present paradigm suggests that TEM and TCM cells follow a linear differentiation pathway from naive T cells to effector T cells to TEM cells to TCM cells. We show here that naive T cell precursor frequency profoundly influenced the pathway along which CD8+ memory T cells developed. At low precursor frequency, those TEM cells generated represented a stable cell lineage that failed to further differentiate into TCM cells. These findings do not adhere to the present dogma regarding memory T cell generation and provide a means for identifying factors controlling memory T cell lineage commitment.

Based on homing characteristics and effector functions, at least two types of memory T cells have been described in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations. The original descriptions of central and effector memory T cells suggested that central memory T cells (TCM cells) reside in lymphoid organs and express CCR7 and CD62L, whereas effector memory T cells (TEM cells) reside mainly in nonlymphoid tissues, do not express CCR7 or CD62L and have immediate effector functions1–3. This raised the question of how TCM cells and TEM cells are generated and whether each is the product of interdependent or separate lineages.

Three models of differentiation have been proposed, with the first being that TCM cells provide a continual source of TEM cells. This model is based on the findings that memory CCR7+ T cells in short-term in vitro culture can lose expression of this chemokine receptor and in the process become functionally competent1,4. Analysis of the T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire of human blood memory CD8+ T cells has suggested an additional possibility in which TCM and TEM cells represent mostly separate lineages5. In contrast, an alternative model has indicated that over time TEM cells convert to TCM cells6. This conclusion was derived from analysis of TCR-transgenic CD8+ memory T cells specific for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) glycoprotein 33 (gp33) that had been separated by virtue of CD62L expression. In this system, adoptively transferred CD62L− memory T cells convert to CD62L+ memory cells, however, the reverse does not occur. This discordance between models of memory CD8+ T cell lineage development may be due in part to differences in experimental systems or could reflect a fundamental difference between human and mouse CD8+ memory T cells.

To address those discrepancies, we have compared here the generation of memory cell lineages in adoptively transferred TCR-transgenic CD8+ T cells versus endogenous CD8+ T cells responding to the same infection in vivo. Our results indicated that commitment to a particular memory cell lineage was governed by the initial naive T cell precursor frequency. Moreover, the differentiative and proliferative capacity of memory cell subsets was dependent on the amount of initial clonal competition.

RESULTS

TEM cells revert to TCM cells in adoptive transfer systems

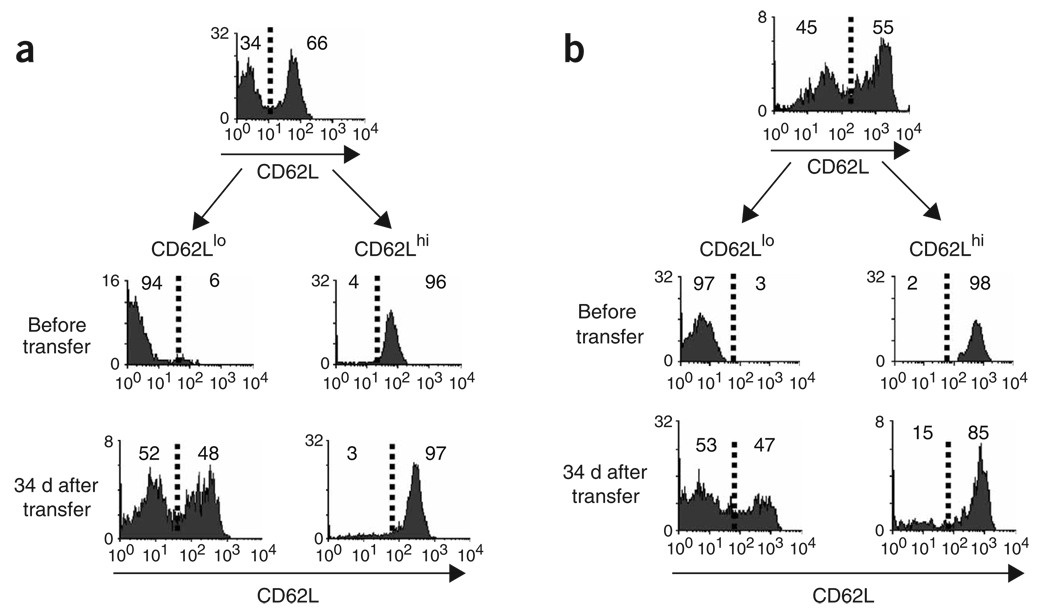

We first tested whether the conversion of TEM cells to TCM cells occurred when adoptively transferred naive TCR-transgenic T cells were the responding population. For this, we adoptively transferred naive LCMV-specific P14 cells into naive mice, which we then infected with the Armstrong strain of LCMV7. The LCMV-specific CD8+ T cell response is characterized by an expansion phase, peaking on days 7–8, followed by a contraction phase between days 8 and 30; subsequently, a stable pool of P14 TCR–transgenic memory cells specific for an H-2Db-restricted epitope of the LCMV glycoprotein, consisting of amino acids 33–41 (KAVYNFATM), is formed8,9. About 60% of the resulting P14 memory cells were CD62L+ (Fig. 1). We sorted LCMV-specific memory CD8+ T cells into TCM and TEM subsets on the basis of CD62L expression 40 d later and adoptively transferred the cells into naive recipients. At 34 d after transfer of sorted P14 TEM cells (CD62Llo) and TCM cells (CD62Lhi) into separate hosts, a portion (48%) of TEM cells had converted to TCM cells (Fig. 1a), whereas transferred CD62Lhi cells retained CD62L expression. We obtained similar results when we sorted P14 cells and transferred them 117 d after infection (data not shown). To determine whether this phenomenon was unique to P14 cells and LCMV infection, we transferred ovalbumin-specific OT-I CD8+ T cells and infected the recipients with vesicular stomatitis virus expressing ovalbumin (VSV-OVA)10. Then, 56 d later we sorted OT-I memory CD8+ T cells into TCM and TEM subsets on the basis of CD62L expression and adoptively transferred the cells into naive recipients (Fig. 1b). After 34 d, the transferred CD62Lhi TCM population remained CD62Lhi, whereas approximately half of the CD62Llo population had converted to CD62Lhi, confirming the ability of OT-I TEM cells to acquire the phenotype of TCM cells.

TEM cells convert to TCM cells when derived from adoptively transferred TCR-transgenic CD8+ T cells. (a) Splenocytes from mice transgenic for the TCR specific for an H-2Db-restricted epitope of the LCMV glycoprotein consisting of amino acids 33–41 (P14; 1 × 106 cells per mouse) were transferred into syngeneic (B6 × B6D2) F1 mice that were infected intraperitoneally 1 d later with LCMV Armstrong (2 × 105 PFU). At 40 d after infection, CD62Llo and CD62Lhi memory T cells from the spleen were purified by flow cytometry and were adoptively transferred into separate naive mice. After 34 d, CD62L expression by splenic H-2Db–gp33+CD8+ T cells of recipients was assessed. Data represent one of three mice per time point. (b) Splenocytes (1 × 105) from CD45.1 OT-I TCR–transgenic mice were transferred into CD45.2 B6 mice, which were infected intravenously 1 d later with VSV-OVA (1 × 106 PFU). At 56 d after infection, CD62Lhi cells from the spleen and CD62Llo memory T cells from the spleen were purified by flow cytometry and were adoptively transferred into separate naive mice. Between 34 and 40 d, CD62L expression by splenic OVA-specific memory T cells of recipients was assessed. Data are from one representative mouse of three to four mice analyzed per time point from three individual experiments. Vertical axes, relative cell number; numbers to the right or left of the dashed vertical line (which represents negative control staining) indicate the percentage of cells in that area.

Stable TEM cell generation from endogenous CD8+ T cells

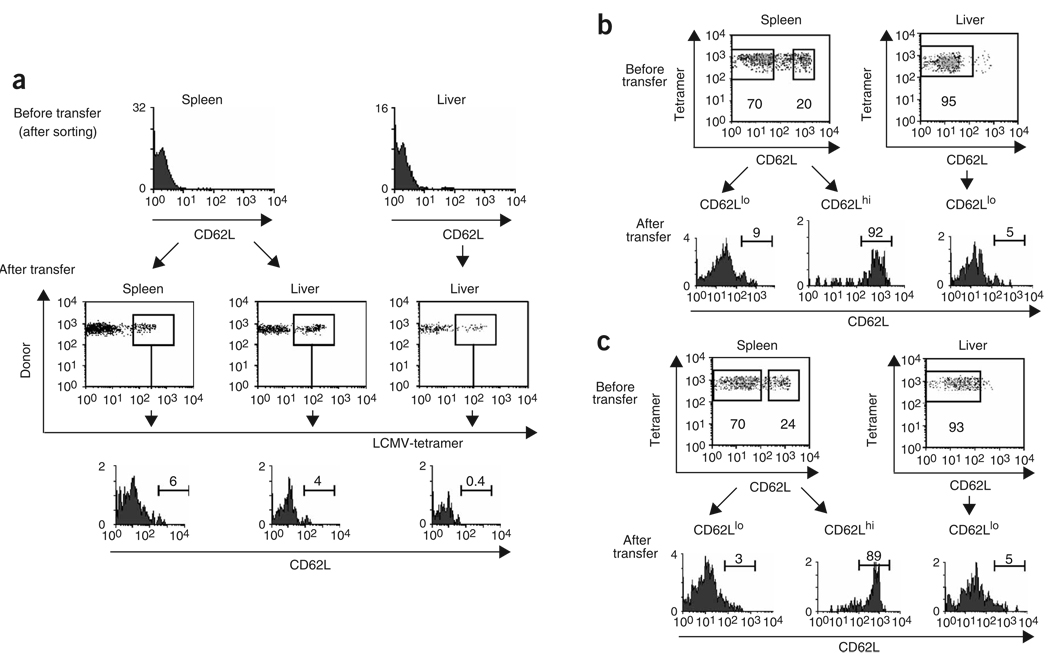

To determine whether the conversion of TEM cells to TCM cells was also characteristic of polyclonal populations of CD8+ memory T cells, we generated memory cells by infecting naive C57BL/6 (B6) mice with LCMV. In this setting, an LCMV-specific CD8+ memory cell population, consisting of 40% CD62Llo and 60% CD62Lhi cells, developed in the spleen 111 d after infection (data not shown), at which time we sorted memory cells from spleen or liver into CD62Llo and CD62Lhi populations and adoptively transferred them into naive mice. Unexpectedly, at 34 d after transfer, the gp33-specific TEM (CD62Llo) population remained uniformly CD62Llo in both the spleen and liver, indicating that the endogenous LCMV-specific TEM cells did not give rise to TCM cells (Fig. 2a). Similarly, CD62Llo CD4+ T cells transferred from LCMV-immune mice into naive recipients remained CD62Llo, although we did not have the means to track LCMV-specific CD4+ T cells in this case (data not shown). We also noted a lack of conversion from TEM to TCM when we sorted endogenous OVA-specific memory CD8+ T cells from VSV-OVA-infected mice into CD62Lhi and CD62Llo subsets and adoptively transferred them into naive recipients. At 34 d after transfer of CD62Llo memory cells from spleen or liver, very few CD62Lhi OVA-specific memory cells could be detected in either the spleen or liver of recipients (Fig. 2b). In addition, CD62Llo secondary memory cells generated by challenge of VSV-OVA-infected mice with Listeria monocytogenes producing OVA (LM-OVA) also did not re-express CD62L after transfer (Fig. 2c). These results suggested that unlike CD62Llo CD8+ T cells generated in the TCR adoptive transfer model (Fig. 1), TEM cells derived from endogenous CD8+ T cells represented a phenotypically stable population.

Endogenous CD8+ T cells generate distinct TCM and TEM lineages in response to infection. (a) CD45.2 B6 mice were infected intraperitoneally with LCMV Armstrong (2 × 105 PFU) and, 111 d after infection, CD62Llo CD8+ memory T cells from the spleen or liver were purified by flow cytometry and were transferred into naive CD45.1 B6 mice. At 34 d after transfer, CD62L expression was assessed in tetramer-positive memory CD8+ T cells (boxes indicate the population analyzed). (b) CD45.2 B6 mice were infected intravenously with 1 × 106 PFU of VSV-OVA and, 90 d later, purified CD62Llo and CD62Lhi OVA-specific memory CD8+ T cells were transferred into CD45.1 B6 mice. Then, 34 d later, CD62L expression was assessed in the OVA-specific memory CD8 T cells. (c) CD45.2 B6 mice originally infected intravenously with 1 × 103 CFU of LM-OVA were allowed to ‘rest’ for 132 d and were reinfected intravenously with 1 × 106 PFU of VSV-OVA. At 75 d after reinfection, CD62Llo and CD62Lhi memory T cells from the spleen or liver were purified by flow cytometry and were transferred into CD45.1 B6 recipients; 34 d later,CD62L expression was assessed in the transferred tetramer-positive population. Data represent three to four mice per time point from three to four individual experiments. Vertical axes, relative cell number; numbers above bracketed lines indicate the percentage of cells expressing CD62L in that area. Boxes (b,c) indicate the gates used for cell sorting; numbers beneath boxes indicate the percentages of the initial populations within the sort gates.

To allow long-term tracking of transferred TEM cells to further address whether interconversion occurs, we transferred purified TEM cells and then ‘recalled’ these cells with infection. At 107 d after infection, CD62L+ cells were still not evident (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). Although conversion could ensue at later times and/or secondary infection could further delay conversion, given the lifespan of the mouse, it becomes difficult to see the utility of such a system. Instead, we believe that separate TCM and TEM lineages are generated in the primary response and that TCM cells are generally sequestered in lymph nodes and recirculate preferentially through lymph nodes, where they participate in secondary responses.

Precursor frequency governs memory lineage commitment

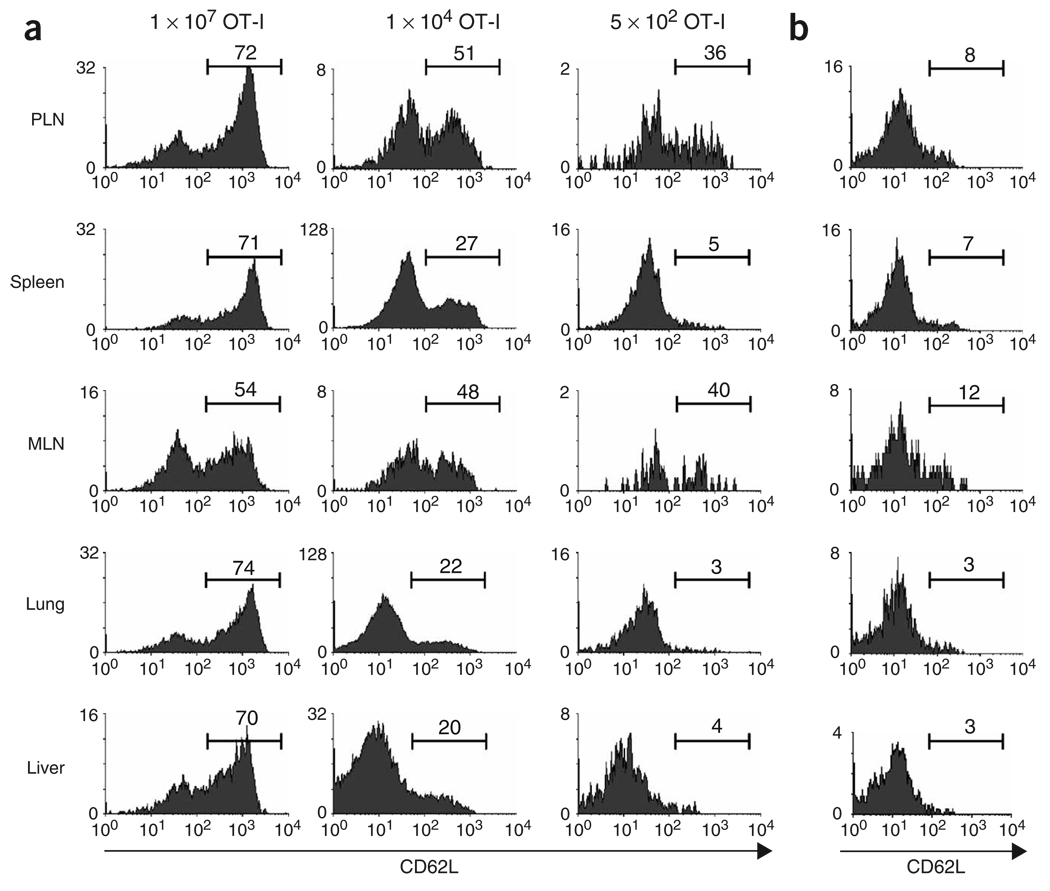

One possible explanation for the discrepancies we noted between TCR-transgenic and endogenous T cells was the fact that the naive precursor frequency was much greater in the former than in the latter. To test whether precursor frequency affected lineage commitment, we adoptively transferred varying numbers of OT-I T cells into B6 mice, which we then infected with VSV-OVA. At 42 d after infection, we analyzed CD62L expression in transferred transgenic cells from various tissues. Although the total number of OVA-specific memory T cells in the spleen was relatively constant (including both transgenic and endogenous cells; data not shown), the absolute numbers of TEM cells and TCM cells differed depending on the number of OT-I T cells transferred (Fig. 3a). Thus, at 42 d after infection of recipients of 1 × 107, 1 × 104 or 5 × 102 OT-I T cells, the percentage of splenic TCM (CD62Lhi) cells was 71%, 27% or 5%, respectively. We noted the same trend in the lung and liver (Fig. 3a) and obtained similar results for CCR7 expression (data not shown). At the lowest dose of 5 × 102 cells, only the memory cell population in the lymph nodes contained an appreciable population of CD62Lhi cells. This phenotypic distribution among memory cells more closely resembled that derived from an endogenous response (Fig. 3b), which is likely to be initiated from a precursor pool of a few hundred cells11.

Initial naive CD8+ T cell precursor frequency ‘imprints’ memory lineage commitment during the primary response. (a) OT-I splenocytes (1 × 107, 1 × 104 or 5 × 102) were transferred into B6 mice and 1 d later the mice were infected with 1 × 106 PFU VSV-OVA. At 42 d after infection, lymphocytes were isolated from various tissues and CD62L was measured on the OT-I T cells. (b) B6 mice were infected with 1 × 106 PFU VSV-OVA and 42 d after infection, CD62L was measured on the tetramer-positive memory CD8+ T cells. Data represent five mice (1 × 107 and 1 × 104 OT-I) and six mice (5 × 102 OT-I) from two individual experiments. Vertical axes, relative cell number; numbers above bracketed lines indicate the percentage of OT-I cells in that area. PLN, peripheral lymph node; MLN, mesenteric lymph node.

To test whether altering the ratio of antigen-presenting cells to CD8+ T cells during the primary response affected memory lineage ‘choice’, we artificially increased dendritic cell numbers by treatment with the ligand for the cytokine receptor Flt3. Administration of Flt3 ligand resulted in an increase of about five- to sevenfold in dendritic cells in the spleen and lymph nodes (data not shown). We transferred 1 × 105 OT-I cells into mice treated with Flt3 ligand that we then infected with VSV-OVA. Then, 67 d later, we assessed the expression of CD62L by OT-I cells. In control mice, 60% of the memory cells expressed CD62L, compared with only 7% of memory cells in mice treated with Flt3 ligand (Supplementary Fig. 2 online). Thus, increasing dendritic cell numbers enhanced TEM cell generation. Although the precise mechanism that resulted in enhancement of TEM cell generation has yet to be defined, an increase in dendritic cells should result in a situation in which T cell competition for antigen is decreased, thereby allowing more complete T cell activation. These data further support our contention that T cell precursor frequency and competition for resources are important physiological regulators of memory CD8+ T cell lineage commitment.

Memory lineage commitment during the primary response

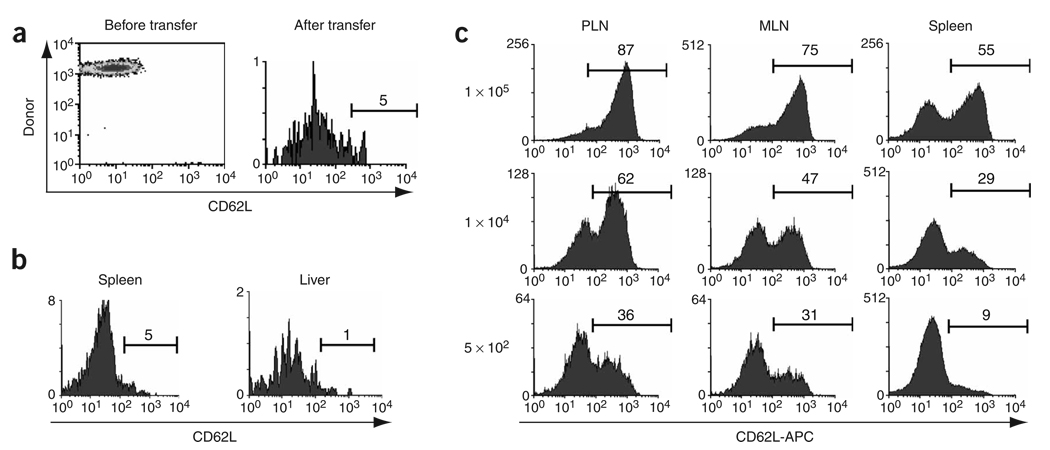

The results reported above led us to investigate whether lineage commitment after transfer of low numbers of OT-I cells mimicked our observations with endogenous memory cells; that is, whether CD62Llo memory cells from these mice would maintain their phenotype after adoptive transfer. We transferred 5 × 102 OT-I cells into naive mice and infected the recipients with VSV-OVA. Then, 8 d later, we isolated CD62Llo effector cells and transferred them into naive mice; we used early transfer to test whether commitment to a particular lineage occurred early during the immune response. These cells remained CD62Llo when examined 1 month later (Fig. 4a). Hence, when generated from low numbers of precursors, CD8+ TEM cells acquired a stable CD62Llo phenotype as early as 8 d after activation. This was not dependent on transfer early after activation, however, as secondary CD62Llo memory cells, derived from 5 × 102 OT-I cells after infection with VSV-OVA and rechallenge with LM-OVA, did not convert to TCM cells (Fig. 4b). Thus, despite the fact that the precursor frequency of antigen-specific cells was substantially increased after secondary infection, the resulting TEM cells did not undergo conversion to TCM cells, suggesting that the lineage ‘choice’ was established in the primary response.

Commitment to the TCM and TEM lineages occurs during the primary response. (a) CD45.1 OT-I cells (5 × 102) were transferred into CD45.2 B6 mice and 1 d later the mice were infected with 1 × 106 PFU VSV-OVA. Then, 8 d later, CD62Llo OT-I cells were purified by flow cytometry and were adoptively transferred into naive B6 mice; 34 d later, the expression of CD62L by splenic OT-I cells was assessed. (b) B6 mice received an initial adoptive transfer of 5 × 102 OT-I cells and were infected with VSV-OVA, then were allowed to ‘rest’ for 114 d and were infected intravenously with 1 × 103 CFU of LM-OVA. Then, 48 d later, CD62Llo memory T cells from the spleen or liver were purified by flow cytometry and were transferred into naive recipients; 34 d after transfer, CD62L expression by OT-I cells from the spleen and liver was assessed. (c) OT-I splenocytes (1 × 107, 1 × 104 or 5 × 102) were transferred into B6 mice and 1 d later mice were infected with 1 × 106 PFU VSV-OVA. At 7 d after infection, lymphocytes were isolated from the peripheral lymph node, mesenteric lymph node and spleen, and CD62L was measured on the OT-I T cells. APC, allophycocyanin. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. Vertical axes, relative cell number; numbers above bracketed lines indicate the percentage of cells in that area.

To further substantiate that commitment to the TCM or TEM lineages occurred during the primary response, we transferred 1 × 105, 1 × 104 or 5 × 102 OT-I (CD45.1) cells into B6 (CD45.2) recipients that we then infected with VSV-OVA. Then, 7 d later we determined the percentages of CD62Llo and CD62Lhi OT-I T cells (Fig. 4c). As with the memory populations, increasing the input number of antigen-specific T cells resulted in increasingly larger populations of CD62Lhi cells in the lymph node and spleen. When 5 × 102 OT-I cells were transferred, most effector cells in the spleen lacked CD62L, whereas those populations in lymph nodes contained about one third CD62Lhi cells. Thus, sampling only the spleen, as is often done, would provide misleading results regarding CD62L expression. Because CD62L is used by T cells to enter lymph node, enrichment of CD62L+ cells in this tissue might be expected. Our results suggested that precursor frequency determined lineage commitment during the primary response.

Initial precursor frequency influences TEM cell proliferation

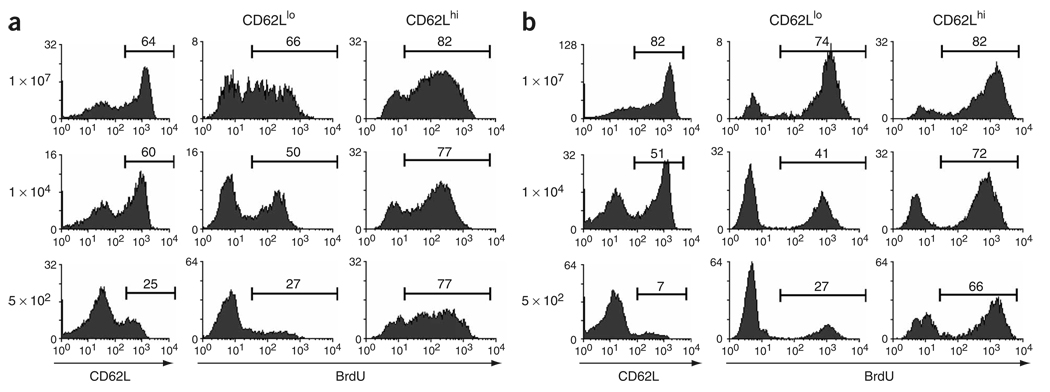

Our results suggested that CD62Llo CD8+ memory cells generated from high or low numbers of naive cells were fundamentally different, with only the latter representing a phenotypically stable population. To investigate this possibility further, we assessed the kinetic activity of these cells in vivo. A study of mouse CD8+ memory cells has suggested that TCM cells have a greater capacity for proliferation than do TEM cells6. Thus, we sought to assess whether precursor frequency during the primary response affected the proliferative capacity of the memory cells generated. We adoptively transferred 1 × 107, 1 × 104 or 5 × 102 OT-I T cells into B6 mice and infected the mice with VSV-OVA 1 d later. We infected the mice with LM-OVA 198 d later and at least 40 d after secondary infection, we provided the mice with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) in their drinking water for an additional 40 d. Splenic memory cell populations derived from 1 × 107 or 1 × 104 OT-I cells were about 60% CD62Lhi, whereas only about 25% of those derived from 5 × 102 OT-I cells expressed CD62L (Fig. 5a). At all input doses, more than 75% of the CD62Lhi memory cells had incorporated BrdU. In contrast, the BrdU incorporation of the CD62Llo cells was highly dependent on the input number of T cells. Thus, 66%, 50% and 27% of CD62Llo cells incorporated BrdU when 1 × 107, 1 × 104 and 5 × 102 OT-I cells were transferred, respectively. This difference in the proliferative capacity of CD62Llo cells was even more substantial in the lung, with 74%, 41% and 27% BrdU+ cells after transfer of 1 × 107, 1 × 104 or 5 × 102 OT-I cells, respectively (Fig. 5b). We also noted this difference in proliferative capacity in the CD62Llo population in the peripheral lymph nodes and liver (data not shown). In addition, we also noted this difference in experiments examining proliferation of primary endogenous TEM cells and TCM cells and with primary memory cells generated from low numbers of transferred OT-I cells. Thus, in general it seems that TEM cells have lower proliferative capacity than TCM cells (data not shown). These data show that the initial precursor frequency of antigen-specific T cells ‘imprinted’ fundamental physiological differences on the memory cells generated and that these differences were maintained even through a secondary recall response.

Proliferative capacity of TEM cells is regulated by clonal competition. CD45.2 B6 mice received an initial adoptive transfer of 1 × 107, 1 × 104 or 5 × 102 CD45.1 OT-I T cells and were infected with VSV-OVA, then were allowed to ‘rest’ for 198 d and were infected intravenously with 1 × 103 CFU of LM-OVA. Then, 40 d later, mice were provided with BrdU in their drinking water for 40 d, at which time BrdU incorporation was analyzed in CD62Llo and CD62Lhi OT-I cells from the spleen (a) and lung (b). Data represent three mice (1 × 107 and 1 × 104 OT-I cells) and five mice (5 × 102 OT-I cells) from two individual experiments. Numbers above bracketed lines indicate the percentage of cells in that area.

Our findings suggested a model of CD8+ memory T cell lineage commitment in which high initial naive T cell precursor frequency resulted in the development of TEM and TCM cells but also of a transitional CD62L− memory subset with the proliferative capacity of CD62L+ memory cells and the ability to re-express CD62L (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). In contrast, in physiological conditions of low initial precursor numbers, distinct TEM and TCM lineages developed without the ability to interconvert (Supplementary Fig. 3 online).

DISCUSSION

At present, the idea of memory T cell development is based on the finding that memory T cells can be divided into subsets distinguishable by the expression of homing molecules and chemokine receptors including CD62L and CCR7 (refs. 1–3). In addition, TCM (CD62L+CCR7+) cells lack immediate effector function, thus functionally distinguishing them from TEM (CD62L−CCR7−) cells2,3. Therefore, based on migratory abilities, TEM cells ‘preferentially’ reside in nonlymphoid tissues, whereas TCM cells can be found in the spleen and lymph node1–3, although these phenotypes and locations are by no means absolute12. Nevertheless, both TEM cells and TCM cells are members of a blood-borne pool of memory cells able to circulate to most tissues of the body, depending on the expression of the appropriate homing molecules for entry into a given tissue13.

The lineage relationship between TCM and TEM cells has been the topic of several reports. For example, based on in vitro studies using human T cells, it was proposed that TCM cells could provide a continual source of TEM cells that were considered end-stage cells1. In contrast, analysis of the TCR repertoires of human memory T cell subsets indicated that the lineages develop independently5. To directly test lineage relationships among memory T cell subsets, an experimental model using adoptive transfer of TCR-transgenic CD8+ T cells and LCMV infection was used6. Transfer of purified CD62L+ or CD62L− memory cells demonstrated that TEM cells are able to convert to TCM cells over several weeks. Our results presented here have corroborated those findings with transfer of LCMV- or OVA-specific TCR-transgenic T cells. However, conversion of TEM cells to TCM cells occurred only in a subset of the TEM cells, at least in the time frame studied, suggesting that there may be lineage heterogeneity in the TEM population. Indeed, our results have shown that the ability of TEM cells to convert to TCM cells increased with the transfer of larger numbers of naive CD8+ T cells. In fact, when we transferred memory cells derived from 5 × 102 naive OT-I cells or when we used endogenous memory cells, we did not note conversion of CD62L− cells to CD62L+ cells. Coupled with that result was the finding that the proliferative capacity of CD62L− cells also increased with increasing input numbers of responding CD8+ T cells. Those data indicated that with nonphysiologically high numbers of responding CD8+ T cells, commitment to the TEM lineage seemed incomplete. This resulted in the production of a ‘transitional’ TEM population with the proliferative capacity of a TCM population and the ability to phenotypically convert to TCM cells. Thus, the protracted development of memory CD8+ T cells proposed using gene expression analysis of responders derived from the transfer of large numbers of TCR-transgenic T cells bears reexamination14.

Our findings indicated that TEM and TCM CD8+ cells represented stable memory cell lineages when generated from physiologically low numbers of naive precursors. Based on those data, we propose a model in which naive CD8+ T cells develop into effector cells and generate memory cells of two distinct lineages based on CD62L expression. Our data would support the idea that the memory lineage ‘decision’ is made during the primary response, as the early phenotype of responding cells was dictated by the naive precursor frequency. In fact, with low numbers of transferred cells or with assessment of the endogenous response, small numbers of CD62L+ cells were present in the lymph node but not the spleen throughout the primary response. The link between precursor frequency and differentiation stage suggested that competition for limiting resources (such as access to antigen-presenting cells15 or cytokines such as interleukin 7 or 15; refs. 16–19) may be involved. This hypothesis was further supported by the demonstration that increasing the ratio of antigen-presenting cells to CD8+ T cells preferentially drove TEM cell development.

The fact that greater numbers of TCM cells and transitional TEM cells were produced when antigen-specific T cell frequencies were high fits with the idea that relatively weak signaling favors TCM cell generation, whereas production of TEM cells requires strong signaling, a model that has been proposed based on in vitro studies1,20. In a published study using transfer of TCR-transgenic T cells, low-dose virus infection resulted in what was interpreted as a more rapid conversion of TEM cells to TCM cells, whereas high-dose infection preferentially generated CD62Llo T cells, and the appearance of CD62Lhi memory cells was extended6. In that study, the amount of antigen was not measured and only blood was analyzed and no cell sorting or adoptive transfers were done. Thus, conversion was never directly demonstrated; the study only showed that the phenotype of the cells was altered. Reducing the viral dose would probably alter the amount of inflammation induced, which might also affect the outcome of the response. Our results would suggest that these findings may be related to the generation of different ratios of TCM, TEM and transitional TEM cells based on antigen dose and precursor frequency. Thus, at decreasing naive T cell frequencies, which may represent relatively high antigen/T cell ratios, fewer CD62L+ cells will be generated. As these cells show greater homeostatic proliferation than CD62L− memory cells6,21,22, the CD62L+ subset would gradually increase over time rather than being generated from CD62L− memory cells.

It remains possible that the proliferative ability of the memory subsets could affect the conversion of TEM cells to TCM cells. However, if the reduced proliferative capacity of TEM cells is responsible for the reduced differentiation from TEM cells to TCM cells, then our example with an initial precursor frequency of 1 × 104, in which the CD62Llo cells also had lower proliferative capacity than the CD62Lhi memory cells, should have resulted in less conversion of TEM cells to TCM cells. However, even in the face of lower proliferative capacity than CD62Lhi cells, 50% of the cells converted to the CD62Lhi phenotype. This scenario has also been demonstrated in another study in which 5 × 104 P14 TCR–transgenic T cells were transferred6. In that study, although TEM cells had a reduced proliferative capacity, 50% of the TEM cells nevertheless underwent reversion to TCM cells. Therefore, it is unlikely that the reduced proliferative capacity of TEM cells could explain the reduced differentiation from TEM cells to TCM cells using endogenous precursor frequencies. In neither our study here nor in published studies6 was the actual number of ‘convertible’ TEM cells in the overall TEM population known.

Although the efficiency of conversion may also be regulated by precursor frequency, several pieces of data would suggest otherwise. In our studies, even 40 d after transfer of CD62Llo cells, we noted little if any conversion. In addition, when nonlymphoid tissues are monitored long term, few TCM cells are present, particularly in tissues such as the intestinal mucosa. Thus, if conversion occurred in normal circumstances, it would have to occur very slowly and mainly in lymphoid tissues, whereas most TEM cells are in nonlymphoid tissues. These data indicate that if conversion occurs in physiologically relevant conditions, then the process seems very inefficient. Given the lifespan of a mouse (about 2 years), this hypothetical slow rate of conversion would perhaps have a minimal effect on the overall process of memory development and reactivation.

Although our experiments have identified precursor frequency as one factor controlling memory lineage development, further studies are needed to elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms involved in memory lineage commitment. Nonetheless, the ability to manipulate memory T cell lineage ‘choice’ at will could provide new therapeutic avenues for vaccine development and immunotherapy. Thus, memory development could potentially be intentionally skewed toward TEM or TCM cells, depending on the infection type or perhaps location of a tumor. It might be expected that TCM cells would be more suitable for protection against infectious agents that prime responses preferentially in lymph node, whereas TEM cells would provide better protection against agents focused in spleen or nonlymphoid tissues. For example, although TEM cells respond poorly to LCMV infection6, TEM cells generate a robust response to pulmonary virus infection23. In any case, ongoing delineation of the signals regulating memory development will continue to provide support for rational vaccine design.

METHODS

Mice and infections

B6 (CD45.2) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. B6 (CD45.1) mice were obtained from Charles River. B6D2 P14 mice bearing the H-2Db–gp33–specific TCR were maintained in the specific pathogen–free unit of the Institute for Animal Health (Compton, UK), and OT-I recombination-activating gene 2–deficient mice bearing the H-2Kb–OVA– specific TCR were bred and maintained in specific pathogen–free conditions at the University of Connecticut Health Center (Farmington, Connecticut). B6 mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong (2 × 105 plaque-forming units (PFU)) by intraperitoneal injection or with VSV-OVA (1 × 106 PFU) intravenously or were challenged intravenously with 1 × 103 colony-forming units (CFU) of LM-OVA24,25. For recall responses, mice originally infected with VSV-OVA were ‘recalled’ with LM-OVA or vice versa.

Isolation of T cell subsets and adoptive transfer

Lymphocytes were isolated from lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues as described2. TCM and TEM cells were purified by flow cytometry on a FACSVantage SE (Becton-Dickinson) or with anti-CD62L magnetic beads (Miltenyl Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity of samples sorted by flow cytometry was 91% for spleen TEM cells, 96% for spleen TCM cells, 92% for liver TEM cells and 90% for liver TCM cells and ranged from 89% to 99% for spleen and liver TCM and TEM cells purified by magnetic beads. Purified TEM or TCM cells were adoptively transferred intravenously.

Flow cytometry

For staining, lymphocytes were resuspended at a density of 1 × 106 to 1 × 107 cells/ml in 0.2% BSA and 0.1% NaN3 in PBS, followed by incubation for 1 h at 25 °C with tetramer-allophycocyanin plus the appropriate dilution of peridinine chlorophyll protein–conjugated antibody to CD8 (anti-CD8; clone 53.6.7; BD PharMingen)26–28. Cells were washed with 0.2% BSA and 0.1% NaN3 in PBS and were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate– conjugated anti-CD11a and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD62L (clone Mel-14; BD PharMingen) and were incubated for at least 20 min at 4 °C, then were washed again and were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS. For adoptive transfer experiments, donor cells were ‘tracked’ with anti-CD45.1– fluorescein isothiocyanate (PharMingen). For staining for CCR7, cells were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with CCL19–immunoglobulin (1 µg/ml), followed by goat anti-human immunoglobulin–biotin and streptavidin-phycoerythrin as described29. For BrdU incorporation studies, mice infected with VSV-OVA were given water containing BrdU (0.8 mg/ml; Sigma) daily for 4 weeks30. BrdU staining was done after cell surface staining31. Cells were treated for 15 min at 25 °C with FACS Lysing Solution (Becton Dickinson), followed by overnight fixation at 4 °C in 1% paraformaldehyde and 0.05% Nonidet-P40 in PBS. Cellular DNA was then denatured for 30 min at 37 °C with 50 Kunitz units of DNase I (Boehringer Mannheim) before being stained for 45 min with anti-BrdU (Becton Dickinson) in 5% FBS and 0.5% Nonidet-P40 in PBS. Cells were washed twice before flow cytometry. Relative fluorescence intensities were measured with a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson). Data were analyzed with WinMDI software (J. Trotter, The Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, California).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Gran and A. Worth for flow cytometry sorting, and Q. Pham for technical assistance. Supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI41576; DK45260 to L.L.; and AI053970 to K.D.K.) and the Edward Jenner Institute for Vaccine Research (publication number 100).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Immunology website.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/ni1227

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.nature.com/articles/ni1227.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/102161954

Article citations

A guide to adaptive immune memory.

Nat Rev Immunol, 24(11):810-829, 03 Jun 2024

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 38831162

Review

Exogenous IL-2 delays memory precursors generation and is essential for enhancing memory cells effector functions.

iScience, 27(4):109411, 04 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38510150 | PMCID: PMC10952031

Synthetically glycosylated antigens for the antigen-specific suppression of established immune responses.

Nat Biomed Eng, 7(9):1142-1155, 07 Sep 2023

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 37679570

Regulation of CD8 T Cell Differentiation by the RNA-Binding Protein DDX5.

J Immunol, 211(2):241-251, 01 Jul 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37265401 | PMCID: PMC10373580

Toward a general model of CD4+ T cell subset specification and memory cell formation.

Immunity, 56(3):475-484, 01 Mar 2023

Cited by: 13 articles | PMID: 36921574 | PMCID: PMC10084496

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (316) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets.

Nat Immunol, 4(3):225-234, 03 Feb 2003

Cited by: 1236 articles | PMID: 12563257

Early signals during CD8 T cell priming regulate the generation of central memory cells.

J Immunol, 185(1):263-272, 02 Jun 2010

Cited by: 88 articles | PMID: 20519649 | PMCID: PMC2997352

Strength of stimulus and clonal competition impact the rate of memory CD8 T cell differentiation.

J Immunol, 179(10):6704-6714, 01 Nov 2007

Cited by: 101 articles | PMID: 17982060

Stem cell-like plasticity of naïve and distinct memory CD8+ T cell subsets.

Semin Immunol, 21(2):62-68, 09 Mar 2009

Cited by: 55 articles | PMID: 19269852

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIAID NIH HHS (5)

Grant ID: R01 AI041576-10

Grant ID: AI053970

Grant ID: AI41576

Grant ID: F32 AI053970

Grant ID: R01 AI041576

NIDDK NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: R01 DK045260

Grant ID: DK45260

Grant ID: R01 DK045260-15