Abstract

Free full text

UNC-129 regulates the balance between UNC-40 dependent and independent UNC-5 signaling pathways

Summary

The UNC-5 receptor mediates axon repulsion from UNC-6/netrin through UNC-40 dependent (‘UNC-5+UNC-40’) and independent (‘UNC-5-alone’) signaling pathways. A requirement for UNC-40 dependent signaling has been shown in long-range repulsion from UNC-6/netrin, however, the mechanisms used to regulate distinct UNC-5 signaling pathways are poorly understood. Here we demonstrate that the C. elegans TGF-β family ligand UNC-129, graded opposite to UNC-6/netrin, functions independent of the canonical TGF-β receptors to regulate UNC-5 cellular responses. We provide evidence that UNC-129 facilitates long-range repulsive guidance of UNC-6 by enhancing ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling at the expense of ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling through interaction with the UNC-5 receptor. This increases the set point sensitivity of growth cones to UNC-6/netrin as they simultaneously migrate up the UNC-129 gradient and down the UNC-6 gradient. Similar regulatory interactions between oppositely graded extracellular cues may be a common theme in guided cell and axon migrations.

Introduction

Patterning of the nervous system requires neurons to extend axons to targets that are often at great distances from their cell bodies. Polarity information can be provided to growing axons by gradients of attractive or repulsive guidance cues that stimulate different signal transduction pathways in growth cones to guide them up or down the gradient, respectively. Previously known guidance cues include UNC-129/BMP, UNC-6/netrins, slits, ephrins and semaphorins (Reviewed in 1).

unc-129 encodes a BMP-like TGF-β superfamily member identified in C. elegans as a suppressor of dorsal migration of the touch receptor axons induced by ectopic expression of UNC-5 in these cells2,3. UNC-129 is expressed by dorsal body muscles and is graded opposite to UNC-6, which is expressed by cells within the ventral nerve cord (VNC)3. As cells and axons are repelled from ventral sources of UNC-6/netrin they migrate down the UNC-6 gradient and simultaneously migrate toward higher concentrations of UNC-129. UNC-129 influences most of the same migrations that are regulated by UNC-6/netrin signaling including the migration of the Distal Tip Cell (DTC) and the guidance of DA, DB, VD, DD, and SDQ motoraxons3–5. Defects in the migration of these cells and axons are not observed in mutants of the type I (SMA-6 and DAF-1) or type II (DAF-4) TGF-β serine/threonine kinase receptors 3. UNC-129 therefore acts via a novel signaling mechanism to regulate ventral to dorsal axon guidance and cell migration.

Navigation using a gradient requires that cells respond appropriately to graded external cues at both high (short range guidance) and low (long range guidance) levels of the cue, but it is unknown how sensitivity to the cue is regulated as the cell or cell extension (e.g., axon growth cone) moves up or down the gradient. In C. elegans, UNC-6 mediated repulsion of motoraxons and DTCs involves two distinct UNC-5 signaling pathways – one that is dependent on the UNC-40 co-receptor (’UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling) and one that is independent of UNC-40 (’UNC-5-alone’ signaling)4. In Drosophila, axons responding to high levels of graded UNC-6/netrin require only ’UNC-5-alone’ signaling, whereas axons responding to low levels require ’UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling6. This suggests that UNC-40 can enhance growth cone sensitivity to low concentrations of UNC-6, raising the possibility that as a growth cone moves down the UNC-6 gradient (e.g., by repulsion) it could enhance its sensitivity to UNC-6/netrin by increasing ’UNC-5+UNC-40’ and decreasing ’UNC-5-alone’ function.

The data presented here show that UNC-129 promotes ’UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling and suggest that UNC-129 also inhibits ’UNC-5-alone’ signaling through direct interaction with the UNC-5 receptor. Thus we propose that UNC-129 functions to increase the sensitivity of the growth cone to continuously lower concentrations of UNC-6/netrin encountered as the growth cone moves down the UNC-6 gradient by interacting with UNC-5 to enhance ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling at the expense of ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling.

Results

UNC-129 promotes ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling

UNC-129/TGF-β regulates the guided migration of cells and axons along the dorso-ventral axis. unc-129 mutants display an uncoordinated phenotype resulting from defects in the proper ventral to dorsal migration of motor axons. Mutants in the classical TGF-β serine/threonine kinase receptors and downstream smads have not been reported to display uncoordinated phenotypes or axon guidance defects. DAF-4 is the only TGF-β type II serine/threonine kinase receptor in C. elegans, and as such, all TGF-β signaling is expected to require DAF-4. daf-4(m63) mutants did not display defects in axon guidance, demonstrating that the axon guidance defects observed in unc-129 mutants are not the result of a decrease in TGF-β signaling. Furthermore, double mutants of daf-4(m63), daf-1(m40) or sma-6(wk7) null alleles with unc-129(ev554) did not inhibit axon guidance defects in the DA, DB motoraxons observed in unc-129 mutants, demonstrating that UNC-129 does not act as a negative regulator of the canonical TGF-β signaling pathways (Supplemental Fig. 1S). Therefore UNC-129 affects axon and cell migrations through a mechanism that does not involve activation or inactivation of classical TGF-β receptor signaling.

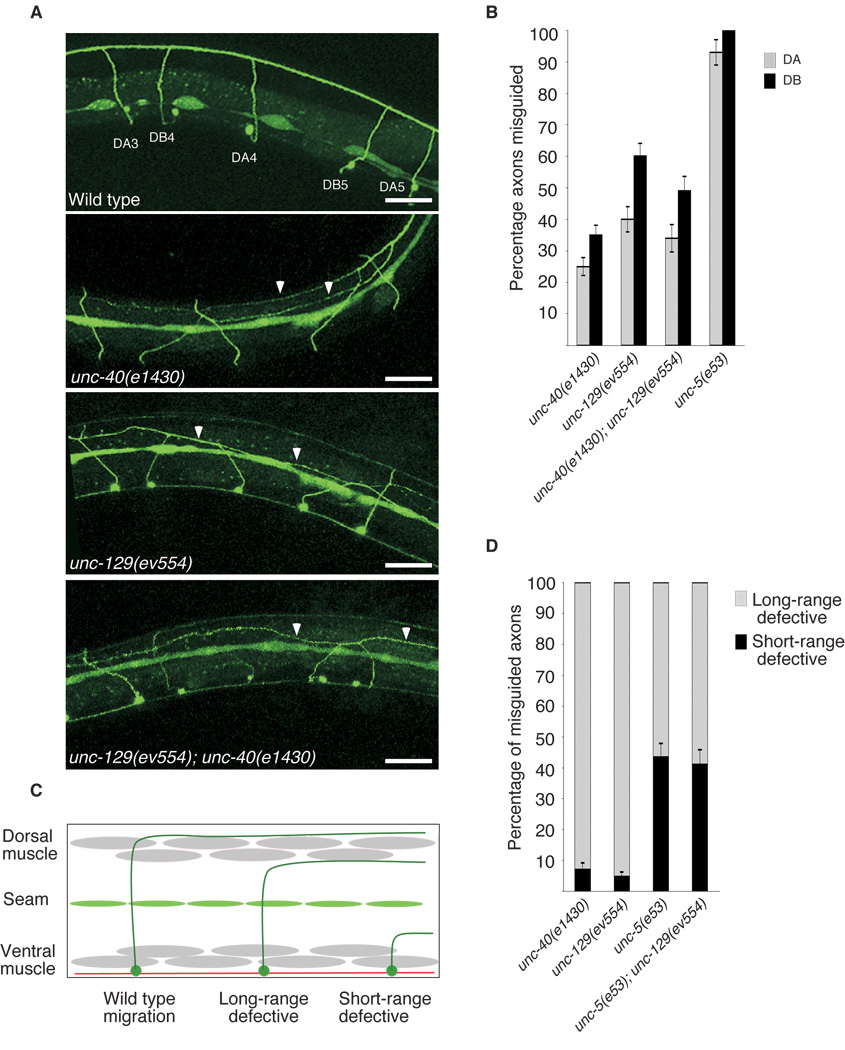

unc-129 mutants share several cell migration and cell association phenotypes with mutants of the UNC-6/netrin signaling pathway. These include defects in ventral to dorsal motor axon guidance, ventral to dorsal DTC migrations3 and separation of sensory rays in the male tail7 (see below). To examine whether UNC-129 might act in the UNC-6/netrin pathway, we looked for enhancement of null alleles of netrin-signaling components by unc-129 mutations. Predicted null alleles of unc-5 and unc-6 have nearly fully penetrant motor-axon guidance defects, precluding a quantitative analysis of the effects of unc-129 mutation in these genetic backgrounds. However, unc-129(ev554) and unc-40(e1430) nulls have similar, incompletely penetrant guidance defects in the DA and DB motor neurons (Fig. 1a and b). We found that unc-129(ev554); unc-40(e1430) doubles are not enhanced for DA and DB motor axon guidance defects indicating that UNC-129 and UNC-40 act in the same signaling pathway to regulate motor axon guidance (Fig. 1a and b). These data suggest that UNC-129 is required to promote ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling in growing axons.

UNC-129 acts in the ’UNC-5+UNC-40’ pathway to regulate axon guidance and DTC migration. (a) evIs82b [unc-129 GFP] shows proper migration of DA and DB motoraxons, whereas unc-40(e1430), unc-129(ev554) and unc-40(e1430); unc-129(ev554) animals show incompletely penetrant axon guidance defects. Arrows indicate misguided axons. Scale bars are 20µm. (b) Quantification of motor axon guidance defects in mutants of the UNC-6/netrin pathway. DA and DB neurons were visualized using evIs82b[unc-129p

GFP] shows proper migration of DA and DB motoraxons, whereas unc-40(e1430), unc-129(ev554) and unc-40(e1430); unc-129(ev554) animals show incompletely penetrant axon guidance defects. Arrows indicate misguided axons. Scale bars are 20µm. (b) Quantification of motor axon guidance defects in mutants of the UNC-6/netrin pathway. DA and DB neurons were visualized using evIs82b[unc-129p GFP]. The percentage of misguided DA (grey) and DB (black) axons in each of the indicated genetic backgrounds are plotted as the mean plus or minus the standard error. n>100 animals for each genotype scored. (c) Diagram showing wild-type axon migration and axons defective in long-range and short-range migration. Axons that are defective in long range migration become misguided in the later part of their migration (dorsal to the seam cells) while axons that are defective in short range guidance become misguided earlier in their migration (on or ventral to the seam cells). (d) Misguided axons in the indicated genetic backgrounds were scored for their degree of misguidance. The unc-129p

GFP]. The percentage of misguided DA (grey) and DB (black) axons in each of the indicated genetic backgrounds are plotted as the mean plus or minus the standard error. n>100 animals for each genotype scored. (c) Diagram showing wild-type axon migration and axons defective in long-range and short-range migration. Axons that are defective in long range migration become misguided in the later part of their migration (dorsal to the seam cells) while axons that are defective in short range guidance become misguided earlier in their migration (on or ventral to the seam cells). (d) Misguided axons in the indicated genetic backgrounds were scored for their degree of misguidance. The unc-129p GFP we used to count axons is weakly expressed in the seam cells; this expression was used as a marker to measure the migration of axons. The percent DA and DB axons that begin migrating longitudinally on or below the seam cells are shown in black, and above the seam cells (on the dorsal muscle band) are shown in grey. Misguided axons in unc-5(e53) mutants begin migrating longitudinally at a more ventral position than those of unc-40(e1430) or unc-129(ev554) mutants.

GFP we used to count axons is weakly expressed in the seam cells; this expression was used as a marker to measure the migration of axons. The percent DA and DB axons that begin migrating longitudinally on or below the seam cells are shown in black, and above the seam cells (on the dorsal muscle band) are shown in grey. Misguided axons in unc-5(e53) mutants begin migrating longitudinally at a more ventral position than those of unc-40(e1430) or unc-129(ev554) mutants.

In Drosophila, ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling is required to guide migrations at a distance (i.e., at the low end of the predicted UNC-6/netrin gradient). ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling is therefore predicted to be more sensitive to lower levels of UNC-6 than ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling6. In order to test whether these two UNC-5 dependent signaling pathways were similarly specialized to short and long-range migration in the C. elegans motor neurons, we asked whether axons in unc-5 mutants were misguided earlier (i.e., closer to ventral sources of UNC-6) in their migration than those of unc-40 and unc-129 mutants (Figure 1c and d). In fact, misguided axons in unc-5(e53) mutants frequently migrate longitudinally along the ventral muscle band or along the lateral seam cells (42%), suggesting defects in short range migration. This occurs only rarely in unc-40(e1430) or unc-129(ev554) mutants (7% and 5% respectively) (Fig. 1d). Instead, misguided axons in unc-40(e1430) and unc-129(ev554) animals migrate mainly along the dorsal muscle band, suggesting that only long range migration is interrupted.

We examined axon guidance defects in animals that were doubly mutant for unc-5(e53) and unc-129(ev554) and found that the severity of axon guidance errors is not worse than in unc-5(e53) mutants, demonstrating that UNC-129 functions within the UNC-5 signaling pathway to regulate axon guidance (Fig. 1d). Together with the inability of the unc-129(ev554) mutation to enhance unc-40(e1430) defects, these data demonstrate that UNC-129 functions in ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling to promote long-range axon repulsion from UNC-6.

If UNC-6/netrin uses two different signaling mechanisms to regulate long range (‘UNC-5+UNC-40’) and short range (‘UNC-5-alone’) migration in C. elegans, then axons that begin their guided migrations at lower concentrations of the UNC-6 gradient (e.g., lateral neurons) are predicted to have a greater requirement for ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling than axons that begin migrating at higher concentrations of UNC-6 present ventrally (e.g., motor axons). AVM/PVM and ALM/PLM cell bodies are located laterally and extend axons that do not initially encounter the high concentrations of UNC-6 present ventrally. Ectopic expression of UNC-5 in these neurons (using a mec7p::unc-5(+) transgene array) results in UNC-6-dependent dorsal re-routing of their axons8. If the model is correct, these migrations should be guided largely through activation of the ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling pathway, since they occur at a distance from ventral sources of UNC-6. In support of this, and our finding that UNC-129 is required for ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling, the unc-129, unc-40 and unc-6 null mutations each caused greater than 90% suppression of these dorsally re-routed migrations2 suggesting that ‘UNC-5 alone’ signaling has a lesser role in guiding axons that begin migrating at lower concentrations of the UNC-6 gradient. Together, these results suggest that UNC-129 and ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ act together to promote increased sensitivity to low levels of graded UNC-6 required for long range repulsive guidance. Furthermore, the requirement for UNC-129 to promote this signaling in C. elegans raises the possibility that in Drosophila the ability of only specific axons to mount a long-range repulsive response may be dependent on the exposure of these cells to an UNC-129/BMP- like molecule.

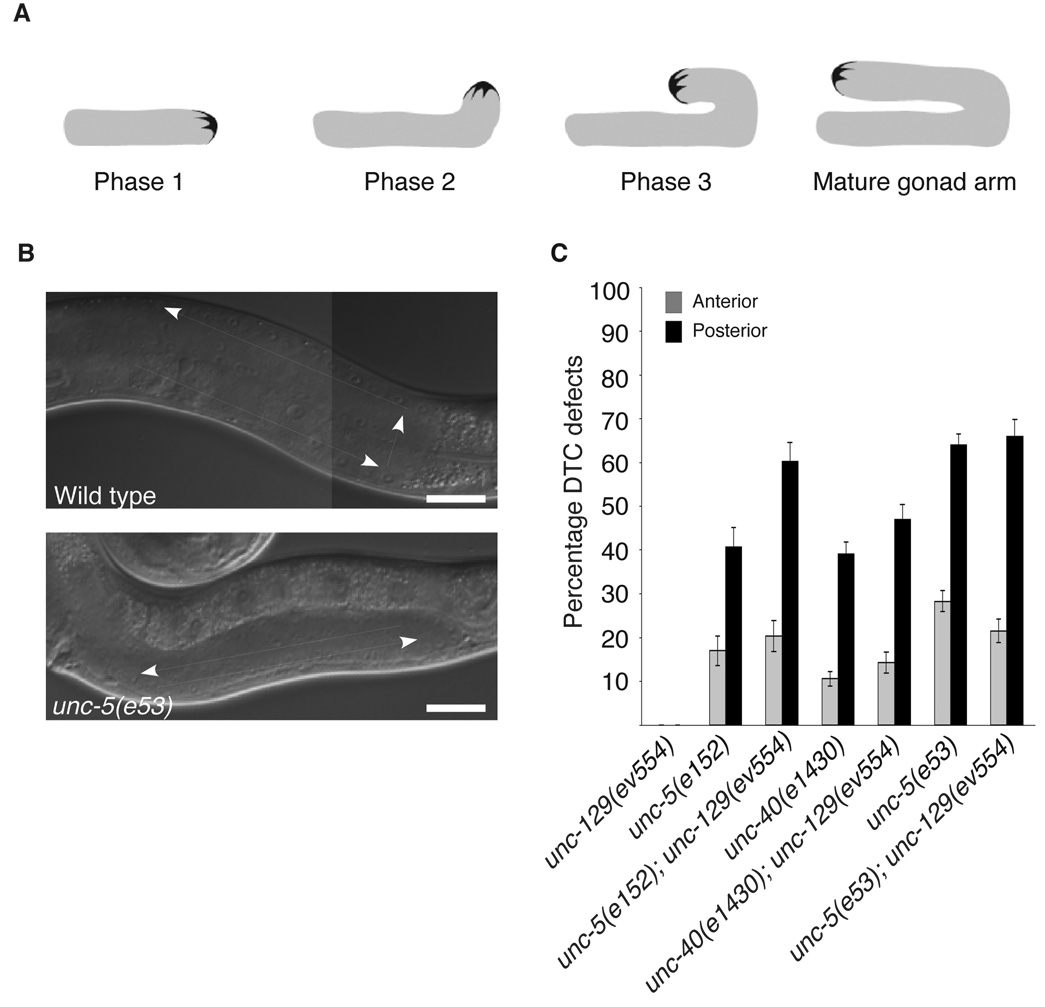

Because UNC-6 signaling through UNC-5 and UNC-40 is required for the proper ventral to dorsal migration of the Distal Tip Cells (DTCs)4, we examined the role of unc-129 in DTC migration. A single DTC is present at the leading edge of both anterior and posterior hermaphrodite gonad arms and each undergoes mirror-image 3 phase migrations that form the U-shaped bi-lobed gonad (Fig. 2a). The two DTCs start out at the ventral midbody. In the first phase of migration, they migrate longitudinally away from each other along the ventral body wall muscle band. In the second phase, the DTCs turn and migrate across the lateral epidermis to the dorsal muscle band. In the third and final phase of migration the DTCs turn on the dorsal side and migrate back toward the mid-body, stopping when they reach the dorsal mid-body region. unc-5, and unc-6 mutants frequently fail to initiate the ventral to dorsal phase 2 migration and execute the phase 3 migration on the ventral rather than the dorsal side of the animal with normal timing (Ref 4 and Fig. 2a,b). The failure to execute the ventral to dorsal migration is also observed, although less frequently, in unc-40(e1430) mutants4. The repulsion of DTCs from ventrally expressed UNC-6 is accomplished through ‘UNC-5 alone’ and ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling. In addition, the ability of unc-40(e1430) null mutants to enhance DTC defects in unc-5(e53) mutants demonstrates that UNC-40 also functions in an UNC-5 independent manner (‘UNC-40-alone’ signaling) in the DTC9. This additional function of UNC-40 may explain why unc-40 mutants display DTC defects while unc-129 mutants do not.

UNC-129 acts in the ’UNC-5+UNC-40’ pathway to regulate DTC migration. (a) Phases of DTC migration in the worm. Shown are the three phases of DTC migration and the shape of the mature gonad. The posterior gonad is represented here. (b) Wild type worm showing proper migration of the DTC and an unc-5(e53) mutant showing a defect in the phase 2 ventral to dorsal migration of the DTC. Note that in the latter, both distal and proximal ends of the gonad are positioned on the ventral side of the animal, thus creating a ventral clear patch caused by displacement of the intestine. Scale bars are 20µm. (c) Quantification of phase two DTC defects in mutant animals. The percentage of misguided anterior (grey) and posterior (black) DTCs of the indicated genetic backgrounds are plotted as the mean plus and minus the standard error. n>100 animals for each genotype scored.

unc-129 mutations enhance the phase 2 DTC defects of the unc-5(e152) hypomorph, demonstrating that UNC-129, and by inference ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling, does play a role, although probably a minor one, in this migration (Ref 9 and Fig. 2a). Interestingly, unc-40(e1430) mutants display weakly penetrant defects in which the DTC begins to migrate dorsally but does not complete the ventral to dorsal migration and instead returns to the ventral side (possibly because it prefers ventral muscle as a substratum for migration) to complete its third phase migration9. This phenotype may be a manifestation of a defect in long-range migration.

To determine if UNC-129 could function in the ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ pathway for initiating DTC migrations, we analyzed double mutants of the unc-129(ev554) null mutation with predicted unc-5, unc-6, and unc-40 null alleles, which cause incompletely penetrant phase 2 DTC migration defects4. Double mutants of unc-129(ev554) and null alleles of either unc-5, or unc-40 fail to show any enhancement of DTC defects (Fig. 2b). The inability of unc-129(ev554) to enhance unc-40(e1430), or unc-5(e53) for phase 2 DTC defects suggests that, as for motor-axon migrations, UNC-129 functions within the ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling pathway to regulate DTC migration.

unc-129 mutations were shown previously to enhance male ray fusions (Erf phenotype) in hypomorphic mab-20(bx61) mutants7. We found that unc-5(e53) and unc-40(e1430) genetic null mutations were also able to significantly enhance ray fusions in mab-20(bx61) males (Fig. 3). To determine whether UNC-129 also acts in the ’UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling pathway in the male tail, we looked for enhancement of the mab-20(bx61);unc-129 double mutant ray fusions by unc-5 or unc-40 mutations (Fig. 3). mab-20(bx61);unc-40(e1430);unc-129(ev554) or mab-20(bx61);unc-5(e53);unc-129(ev554) triple mutants were not enhanced for ray fusions relative to mab-20(bx61);unc-129(ev554) mutants (Fig. 3b). This demonstrates that in the male tail, as for motor axon guidance and initiation of phase 2 DTC migration, UNC-129 is required for ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling.

UNC-129 works in the ’UNC-5+UNC-40’ pathway to prevent male ray fusions. (a) him-5 (high incidence of males) mutant animals show normal tail development. C. elegans males have nine sensory rays on each side of the tail fan (numbers indicate rays). Scale bars are 20µm. (b) unc-129(ev554); unc-40(e1430); mab-20(bx61) males show enhanced ray fusions relative to mab-20(bx61) alone. Shown here, 3 rays, 2, 3 and 4 are fused together. (c) Quantification of ray fusion defects in mutants of the UNC-6/netrin pathway. Rays 7–9 were not quantified because they were often difficult to score. The percent shown for each ray (R) reflects the number of times that ray was present in a fusion. >2R is the penetrance in which more than 2 rays are present in one fusion. n is the number of animals scored. All strains contain him-5(e1467).

UNC-129 can block ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling

In the course of analyzing male ray fusions, we found that unc-129(ev554);mab-20(bx61) double mutants displayed a higher penetrance of fusions in rays 3 and 4 (Fig. 3b- boxed), relative to unc-5(e53);unc-129(ev554);mab-20(bx61) triple mutants, indicating that in the absence of UNC-129 activity, UNC-5 functions inappropriately to cause ray fusions. The inability of unc-40(e1430) to suppress these fusions suggests that UNC-129 acts to block inappropriate ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling. Thus, in preventing male ray fusions, as in motor axon guidance, UNC-129 is required in the same pathway as ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’, but can also block ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling.

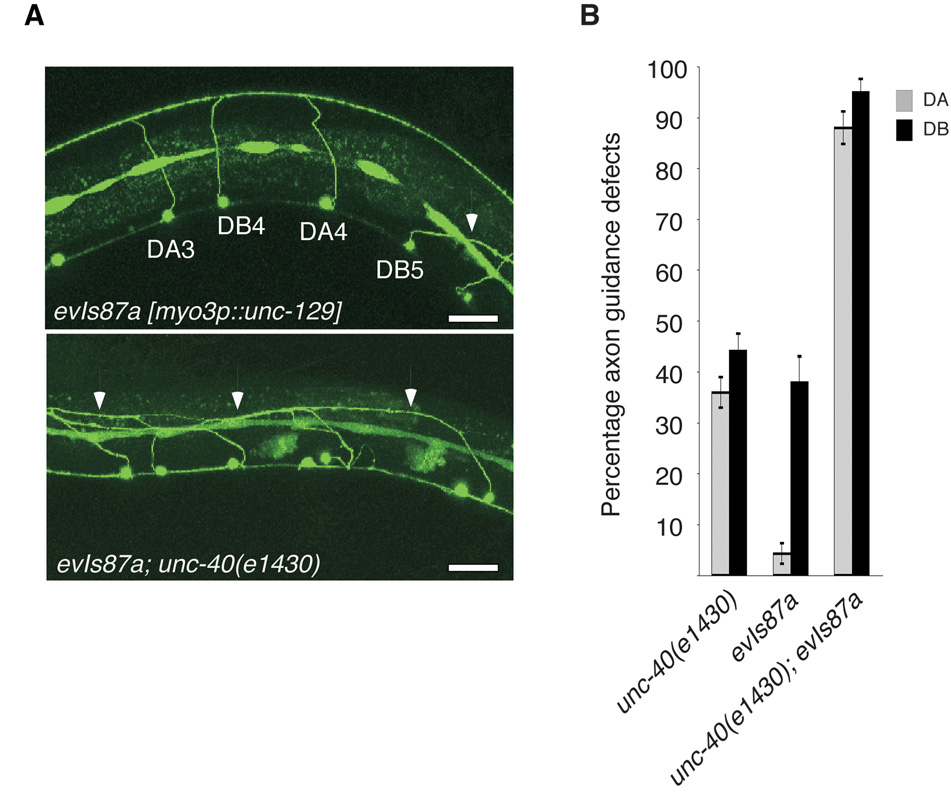

If UNC-129 promotes ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling, it might do so by converting ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling to ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling. Substantial support for this idea is provided by the analysis of animals ectopically expressing UNC-129. Similar to unc-129 mutations, ectopic expression of UNC-129 in the ventral and dorsal muscles using the myo-3 promoter (using transgene array evIs87a [myo-3p::unc-129(+); dpy-20(+)]) also causes defects in the guidance of the commissural motor axons3. In order to further investigate the cause of these defects, we introduced unc-40(e1430) into evIs87a. In contrast to the lack of enhancement observed in unc-129(ev554);unc-40(e1430) double mutants, unc-40(e1430) enhanced evIs87a axon guidance defects (Fig. 4). This suggests that although UNC-129 is required to promote axon guidance through ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling, ectopic ventral expression of UNC-129 interferes with guidance functions independent of this signaling pathway and given the absence of other signaling pathways most likely does so by interfering with ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling.

Ectopic expression of UNC-129 interferes with ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling. (a) Axon guidance defects in evIs87a [myo3p unc-129(+)] and evIs87a; unc-40(e1430) animals. Arrows indicate misguided axons. DA and DB neurons were visualized using evIs82a [unc-129p

unc-129(+)] and evIs87a; unc-40(e1430) animals. Arrows indicate misguided axons. DA and DB neurons were visualized using evIs82a [unc-129p GFP]. Scale bars are 20µm. (b) Quantitation of axon guidance defects in the indicated backgrounds. DA neurons are represented by grey bars, DB by black bars. DA and DB neurons were visualized using evIs82a [unc-129p

GFP]. Scale bars are 20µm. (b) Quantitation of axon guidance defects in the indicated backgrounds. DA neurons are represented by grey bars, DB by black bars. DA and DB neurons were visualized using evIs82a [unc-129p GFP], numbers represent the percent defective axons plus or minus the standard error.

GFP], numbers represent the percent defective axons plus or minus the standard error.

In contrast to the enhancement of DTC defects in evIs87a animals by unc-40(e1430), neither unc-5(e53) nor unc-5(ev813) null alleles enhanced (Supplemental Figure 2S). This demonstrates that ectopic expression of UNC-129 in the DTCs is able to inhibit ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling, which is precisely the signaling we expect to guide migrations at the highest concentrations of UNC-6 present ventrally. However, the involvement of ‘UNC-40-alone’ signaling in DTC migration9 makes it difficult to assess whether the enhancement of evIs87a by unc-40(e1430) is due to the loss of ‘UNC-40-alone’ signaling or loss of ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling, so although evIs87a clearly inhibits ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling, it might also inhibit ‘UNC-40-alone’ signaling in these cells.

RCM/UNC-5 interacts directly with BMP7

Because UNC-129 is a secreted protein that is required to promote UNC-5+UNC-40 signaling while inhibiting UNC-5-alone signaling, we hypothesized it might do so by binding directly to UNC-5. In order to test this hypothesis, we used a modification of LUMIER, a luciferase-based assay of protein-protein interactions10. Briefly, we tagged UNC-129 at the amino-terminus of the mature protein with Gaussia luciferase (Gluc-UNC-129) and expressed the fusion protein Gluc-UNC-129 in 293T cells. Conditioned media was collected and added exogenously to cells expressing either the UNC-5/HA receptor or control cells. Expressed receptors were then immunoprecipitated and luciferase activity measured. Immunoprecipitates of UNC-5/HA yielded a 7 fold increase in luciferase activity relative to mock transfected cells (no receptor) or cells expressing an equivalent amount of HA-tagged TGF-β type I receptor (Fig 5a). Thus, UNC-129 physically interacts with UNC-5. In order to demonstrate that this is a direct interaction, we examined UNC-5 interactions in cross-linking experiments. Because purified UNC-129 is not available, we labeled mammalian BMP7 with 125I and tested its interaction with UNC-5 or RCM (a mammalian UNC-5 homologue). BMP7 bound directly to both UNC-5 and RCM (Fig. 5b). However, we did not detect binding to UNC-40 (data not shown). The inability of BMP7 to bind to UNC-40 is consistent with our finding that UNC-129 inhibits ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling in the absence of UNC-40 and suggests that UNC-129 interaction with UNC-40 is not required for its function. A saturation curve of BMP7 binding to RCM revealed an affinity of 4 nM for this interaction (Fig. 5c and d), which is similar to that reported for other BMP ligands and their classical type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors11,12.

UNC-129 is an UNC-5 binding protein. (a) UNC-129 is able to bind to UNC-5. Cells expressing the indicated receptors were treated with Gluc-UNC-129. Cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated for the expressed receptors. Data is expressed as the average luciferase units from three separate samples within a single experiment plus and minus the standard deviation. ‘No receptor’ indicates that no receptor was transfected and reflects the background binding in this assay. UNC-5, but not TGF-beta type I Receptor bound to Gluc-UNC-129 as observed by the large increase in luciferase activity. (b) 125I-BMP-7 is able to bind to UNC-5 and the mammalian UNC-5 homologue RCM. Two bands appear for RCM in complex with 125I-BMP7, the full length protein and a smaller cleavage product. RCM has been shown to be caspase cleaved, however, C. elegans UNC-5 lacks this caspase cleavage site. The smaller fragment observed is consistent with the N-terminal cleavage product resulting from caspase cleavage (RCM is C-terminally tagged). This protein is likely immunoprecipitated by dimerization with full-length receptor. (c) 125I-BMP-7 binding to RCM-HA approaches saturation with nanomolar amounts of BMP7. (d) Scatchard plot of saturation binding data for RCM-HA and BMP7 produces an estimated affinity of 4nM.

The ability of BMP7 to bind to both UNC-5 and RCM suggests that mammalian BMP ligands share similar binding properties with UNC-129. Interestingly, at least three mouse BMPs (BMP7, BMP6, and GDF7) are expressed in the spinal cord roof plate while netrin is expressed by the floor plate. This mimics the UNC-129 expression pattern (dorsal) relative to UNC-6 (ventral) in C. elegans. BMP7 is required to promote commissural axon guidance in the spinal cord, as are the mouse homologs of UNC-6/netrin signaling components13. However, the analogy to C. elegans axon guidance is unclear since the vertebrate commissural axons migrate toward the source of netrin, rather than away from it, suggesting that BMP7 does not guide these axons via the same mechanism used by UNC-129 to guide motor axons in C. elegans. However, the spinal accessory motorneurons are better candidates for using BMP7 the way C. elegans uses UNC-129 since their cell bodies and axons migrate from ventral to dorsal in the developing mammalian spinal cord and require both Netrin-1 and DCC/UNC-40 to do so14.

When cell or axon growth cone migrations are guided by a graded cue, the concentration of the cue encountered by the moving cell or growth cone as it moves up or down the gradient is constantly changing. Thus, the migrating cell or growth cone faces a potential problem of being able to respond appropriately to the gradient at different concentrations of the cue. For example, a growth cone responding at low concentrations of a cue gradient should require a more sensitive response than it would if it were responding at high concentrations of the same gradient. In Drosophila, growth cones exposed to low levels of UNC-6/netrin (at a distance from the netrin source) require the ’UNC-5+UNC-40’ pathway for guidance whereas growth cones exposed to high concentrations of the netrin gradient, signal either largely or solely through the ’UNC-5-alone’ pathway6. This suggests that enhanced sensitivity required to respond to low levels of UNC-6/netrin can be acquired by increased signaling through ’UNC-5+UNC-40’. The inability of all neurons expressing these receptors to mount a long-range response suggests that additional factors like UNC-129 are required to promote this long-range guidance at low levels of UNC-6/netrin. We have shown that UNC-129 promotes ’UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling, which is more sensitive to lower concentrations of UNC-6/netrin, while antagonizing ’UNC-5-alone’ signaling, which is specialized to higher concentrations of UNC-6/netrin signaling. A unifying model is that UNC-129 accomplishes this by converting ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling to ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling. Thus, as a growth cone is repelled away from ventral sources of UNC-6, it continually encounters lower levels of UNC-6 and higher levels of the oppositely graded UNC-129. The increased levels of UNC-129 would, in turn, increase sensitivity to UNC-6 by shifting signaling from ‘UNC-5-alone’ to the more sensitive ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling pathway. Thus UNC-129 would cause an appropriate change in the set point sensitivity of the growth cone as it moves down the UNC-6 cue gradient so that the growth cone can still sense and respond to the gradient at UNC-6 levels so low they might not be sensed by UNC-5 alone.

UNC-129 could accomplish the switch from ‘UNC-5-alone’ to ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling by binding to UNC-5 and blocking its interaction with an unidentified protein (X in Supplemental Fig. S3) that promotes ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling. Alternatively, these two signaling pathways may be restricted to different sub-cellular compartments, and UNC-129 may control the trafficking of UNC-5 between these compartments. Trafficking of DCC, an UNC-40 homologue, to lipid rafts following netrin stimulation has been described15. If UNC-129 promotes movement of UNC-5 into lipid raft compartments, it could put UNC-5 into proximity with UNC-40 thereby enhancing ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling at the expense of ‘UNC-5-alone’ signaling. This mechanism would provide strict regulation of ‘UNC-5+UNC-40’ complex formation and function and allow UNC-5 and UNC-40 to function separately in the absence of UNC-129. In either case, the effect of UNC-129 could occur gradually, as cells and growth cones migrate, creating a balance of ’UNC-5-alone’ vs. ’UNC-5+UNC-40’ receptor complexes that is constantly re-adjusted towards ’UNC-5+UNC-40’ signaling as growth cones move farther away from UNC-6 and closer to dorsal sources of UNC-129 or may occur at a specific time or landmark encountered during migration.

Methods

Worms were grown at 20°C using standard techniques16. Strains include: LGI: unc-40(e1430)17. LGIV: unc-5(e53), unc-5(e152)4; unc-129(ev554)2. unc-5(ev813) was sequenced and comprises a deletion of exon 2 in unc-5. LGX: unc-6(ev400)4. evIs87a is integrated transgene array [myo3p::unc-129(+); dpy-20(+)]3. evIs82b or evIs82a [unc-129p::GFP] were used to visualize the DA and DB motorneurons3.

Distal tip cell and axon guidance defects were scored in L4s or early adults. Animals were anesthetized with 1mM levamisole and examined using differential interference contrast (DIC) optics to visualize the gonad. DA and DB motor-axons were scored as defective if they failed to reach the dorsal nerve cord.

Protein Expression

UNC-5:HA was cloned into pCDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). To enhance UNC-5 expression, the N-terminal signal peptide was replaced with the RCM signal peptide and the C-terminal death domain was replaced with an HA epitope. RCM:HA was described previously18. A description of the luciferase based binding assay is available in supplemental materials and methods.

Iodination of BMP7 was performed as described previously19. For cell surface labeling, 293T cells were plated onto poly-L-lysine (Sigma) plates, transiently transfected using calcium phosphate20 and incubated with 4nM 125Iodine labeled BMP7 for 4 hours at 4°C. Cells were washed, crosslinked with Dissuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) (Pierce) and lysed in TNTE (50mM Tris pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) containing 0.5% Triton X-100. Immunoprecipitations were performed using anti-HA, 12CA5 (hybridoma supernatant), followed by incubation with Protein-G sepharose beads (Pharmacia). Beads were washed and boiled in sample buffer then samples were separated on SDS PAGE gels and exposed to phosphoimager cassette or western blotted with anti-HA antibodies (12CA5). To generate saturation curves, increasing amounts of 125I-BMP7 were added to Cos-7 cells expressing RCMHA or the control vector. Cells were treated as indicated above and similarly immunoprecipitated. BMP7 bound to sepharose beads was determined by gamma-ray counting. Each point shown in the Scatchard plot is the average of triplicate samples.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. K. Fujisawa, Dr. T. Kawano, Dr. R. Steven and Dr. C. LeRoy for helpful discussions, Ms. Louise Brown for help with microscopy, Dr. Barrios-Rodiles for help with Luciferase assays and Dr. Satoshi Suo and Ms. Jasmine Plummer for careful reading of the manuscript. Funding for this work was provided by grants from the NIH (JC Grant #NS41397), CIHR (JW, Grant #12860; TP Grant #GSP36651)), the CIHR Barbara Turnbull award (JC Grant #MOP77722) and the Cancer Research Society of Canada (L.M.). JLW and JC are CRC chairs. TP is a Distinguished Scientist of the CIHR. JLW is a HHMI international scholar.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2256

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc2745997?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1038/nn.2256

Article citations

TGF-β ligand cross-subfamily interactions in the response of Caenorhabditis elegans to a bacterial pathogen.

PLoS Genet, 20(6):e1011324, 14 Jun 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38875298 | PMCID: PMC11210861

TIAM-1 regulates polarized protrusions during dorsal intercalation in the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo through both its GEF and N-terminal domains.

J Cell Sci, 137(5):jcs261509, 06 Mar 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38345070

Evolution and Diversity of TGF-β Pathways are Linked with Novel Developmental and Behavioral Traits.

Mol Biol Evol, 39(12):msac252, 01 Dec 2022

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 36469861 | PMCID: PMC9733428

The regulatory landscape of neurite development in Caenorhabditis elegans.

Front Mol Neurosci, 15:974208, 25 Aug 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36090252 | PMCID: PMC9453034

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Atypical TGF-β signaling controls neuronal guidance in Caenorhabditis elegans.

iScience, 25(2):103791, 18 Jan 2022

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 35146399 | PMCID: PMC8819019

Go to all (37) article citations

Other citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

MAX-1, a novel PH/MyTH4/FERM domain cytoplasmic protein implicated in netrin-mediated axon repulsion.

Neuron, 34(4):563-576, 01 May 2002

Cited by: 76 articles | PMID: 12062040

Shared receptors in axon guidance: SAX-3/Robo signals via UNC-34/Enabled and a Netrin-independent UNC-40/DCC function.

Nat Neurosci, 5(11):1147-1154, 01 Nov 2002

Cited by: 101 articles | PMID: 12379860

UNC-6/netrin and its receptors UNC-5 and UNC-40/DCC modulate growth cone protrusion in vivo in C. elegans.

Development, 138(20):4433-4442, 31 Aug 2011

Cited by: 35 articles | PMID: 21880785 | PMCID: PMC3177313

Moving around in a worm: netrin UNC-6 and circumferential axon guidance in C. elegans.

Trends Neurosci, 25(8):423-429, 01 Aug 2002

Cited by: 43 articles | PMID: 12127760

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Howard Hughes Medical Institute

NINDS NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: NS41397

Grant ID: R01 NS041397-01

Grant ID: R01 NS041397