Abstract

Free full text

Extensive Genetic Diversity Identified among Sporadic Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates Recovered in Irish Hospitals between 2000 and 2012

Abstract

Clonal replacement of predominant nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains has occurred several times in Ireland during the last 4 decades. However, little is known about sporadically occurring MRSA in Irish hospitals or in other countries. Eighty-eight representative pvl-negative sporadic MRSA isolates recovered in Irish hospitals between 2000 and 2012 were investigated. These yielded unusual pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and antibiogram-resistogram typing patterns distinct from those of the predominant nosocomial MRSA clone, ST22-MRSA-IV, during the study period. Isolates were characterized by spa typing and DNA microarray profiling for multilocus sequence type (MLST) clonal complex (CC) and/or sequence type (ST) and SCCmec type assignment, as well as for detection of virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes. Conventional PCR-based SCCmec subtyping was undertaken when necessary. Extensive diversity was detected, including 38 spa types, 13 MLST-CCs (including 18 STs among 62 isolates assigned to STs), and 25 SCCmec types (including 2 possible novel SCCmec elements and 7 possible novel SCCmec subtypes). Fifty-four MLST-spa-SCCmec type combinations were identified. Overall, 68.5% of isolates were assigned to nosocomial lineages, with ST8-t190-MRSA-IID/IIE ± SCCM1 predominating (17.4%), followed by CC779/ST779-t878-MRSA-ψSCCmec-SCC-SCCCRISPR (7.6%) and CC22/ST22-t032-MRSA-IVh (5.4%). Community-associated clones, including CC1-t127/t386/t2279-MRSA-IV, CC59-t216-MRSA-V, CC8-t008-MRSA-IVa, and CC5-t002/t242-MRSA-IV/V, and putative animal-associated clones, including CC130-t12399-MRSA-XI, ST8-t064-MRSA-IVa, ST398-t011-MRSA-IVa, and CC6-t701-MRSA-V, were also identified. In total, 53.3% and 47.8% of isolates harbored genes for resistance to two or more classes of antimicrobial agents and two or more mobile genetic element-encoded virulence-associated factors, respectively. Effective ongoing surveillance of sporadic nosocomial MRSA is warranted for early detection of emerging clones and reservoirs of virulence, resistance, and SCCmec genes.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus colonizes the anterior nares of approximately 30% of the human population; it can give rise to a wide range of infections of skin and soft tissues, bones, joints, and prosthetic implants and can be responsible for a variety of toxinoses caused by specific toxins such as toxic shock toxin, enterotoxins, exfoliative toxins, and Panton-Valentine leukocidin (1). Staphylococcus aureus can evolve to methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) upon acquisition of a large staphylococcal chromosomal cassette (SCC) element harboring either the methicillin resistance gene mecA or mecC (SCCmec), both of which encode a modified penicillin-binding protein, PBP 2a (2,–4).

Within SCCmec, mecA or mecC forms part of the mec gene complex, which may also harbor the mec regulatory genes mecI and mecR1, as well as insertion sequences and, in some instances, blaZ (1,–3). Based on various combinations and truncations of the mec complex genes, five classes of the mec gene complex (A, B, C1, C2, and E) have been identified in MRSA (3, 5). In addition, each SCCmec element also harbors a chromosome cassette recombinase (ccr) gene complex, consisting of ccrA and ccrB together or ccrC; these genes encode polypeptides that catalyze site- and orientation-specific integration and excision of SCCmec into orfX within the S. aureus chromosome (1, 6). Seven types of ccr gene complex (types 1 to 5, 7, and 8) have been described to occur in MRSA, each with a different combination of ccrA and ccrB or ccrC alleles (5, 7). SCC elements that carry ccr genes but lack mec genes have also been described, as well as pseudo (ψ) SCCmec and SCC elements that lack ccr genes, individual SCCmec elements with multiple ccr genes, and composite islands (CIs) consisting of two or more elements (5).

Eleven SCCmec types (I to XI) have been described to date for MRSA, each with a different combination of mec class and ccr type (3). Numerous SCCmec subtypes have also been described for MRSA which differ from SCCmec types based on DNA sequence variation or the presence or absence of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) in the joining (J) regions, which are located outside the ccr and mec complexes (7). MRSA isolates often exhibit resistance to a range of antimicrobial agents that can be due to the carriage of multiple antimicrobial resistance genes located on MGEs, including transposons, plasmids, and SCC or SCCmec elements (8, 9).

The first report of MRSA appeared in the literature in 1961, shortly after the introduction of methicillin into clinical use; just 10 years later, in 1971, MRSA was first reported in Irish hospitals (10, 11). Following a major increase in the prevalence of MRSA in Irish hospitals in the late 1970s and during the 1980s and 1990s, it has now been endemic for more than 3 decades (12,–17). Since 1999, the prevalence rate of MRSA among S. aureus strains causing bloodstream infections (BSIs) in Ireland has been monitored by the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net). Annual rates of MRSA among S. aureus from BSIs in Ireland reached 42% (592 MRSA isolates among 1,412 S. aureus isolates) in 2006, the highest level reported to date, and declined in recent years, with a rate of 22.8% (242 MRSA isolates among 1,060 S. aureus isolates) reported for 2012 (18, 19).

Clonal replacement of predominant nosocomial MRSA strains has occurred several times in Ireland during the last 4 decades (20). The different MRSA lineages that predominated in Irish hospitals at different time periods have been well characterized, including ST250-MRSA-I/I-pls (where ST is multilocus sequence type) in the 1970s and early 1980s, ST239-MRSA-III/III-pI258/Tn554 in the middle to late 1980s and early 1990s, and ST8-MRSA-IIA-IIE throughout the 1990s, together with ST36-MRSA-II and ST22-MRSA-IV in the late 1990s; since 2002, the ST22-MRSA-IV clone has dominated (17, 20). Prior to 1999, ST22-MRSA-IV was detected only sporadically among MRSA isolates in Ireland, but by 2003, it accounted for 80% of MRSA BSIs, and despite a decline in the proportion of S. aureus infections due to MRSA in recent years, it has continued to account for 70 to 80% of MRSA BSIs each year (19).

While a limited number of sporadically occurring MRSA clones from patients in Irish hospitals in the 1980s and 1990s have been characterized using multilocus sequence typing (MLST), SCCmec typing, and DNA microarray analysis, e.g., ST5-MRSA-II and ST247-MRSA-Ia, there have been no systematic detailed studies of the genetic diversity of sporadic MRSA strains in Ireland (20, 21). These account for approximately 20 to 30% of MRSA BSIs in Ireland each year, as well as being identified each year among non-BSI isolates submitted to the Irish National MRSA Reference Laboratory (NMRSARL) from patients in hospitals with a variety of infections and from patient and environmental screening samples (19). In fact, the number of sporadic MRSA isolates identified among BSIs in Ireland increased from 12.1% in 2005 to 23.1% in 2011 (19). Numerous studies have shown that many MRSA clones that occur sporadically or not at all in one geographic region are often prevalent in another region and vice versa (20, 22, 23). However, previous studies that have investigated sporadic MRSA populations are limited in terms of sample size and/or depth of analysis (24,–27).

Due to the potential of sporadic MRSA strains to replace currently dominant MRSA clones and because they account for a significant proportion of MRSA infections in Ireland each year, it is essential that populations of new and emerging MRSA strains be monitored. In addition, sporadic MRSA strains may constitute a significant potential reservoir for virulence and resistance genes located on MGEs, in particular SCCmec elements. Therefore, the present study investigated the genotypes, SCCmec types, and virulence and resistance genes within 88 MRSA isolates representative of 1,663 pvl-negative sporadically occurring MRSA isolates from patients in Irish hospitals between 2000 and 2012. Isolates were investigated using spa typing, MLST, SCCmec typing, and DNA microarray profiling. The 88 sporadic MRSA isolates were selected at the NMRSARL based on unusual antibiogram-resistogram (AR) and/or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) typing patterns which were different from that of the endemic strain that predominated in Irish hospitals during the study period, i.e., ST22-MRSA-IV. All pvl-positive MRSA isolates from Irish hospitals and community sources submitted to the NMRSARL for examination during the same period have been investigated as part of a separate study (28).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

MRSA isolates identified by the NMRSARL were deemed to be sporadic if they exhibited unusual AR and/or PFGE typing patterns which were different from those of the endemic strain in Irish hospitals during the study period, i.e., ST22-MRSA-IV. Unusual AR type patterns included those that were different from previously described ST22-MRSA-IV AR (AR06) type patterns. Unusual PFGE patterns were identified using the criteria of Tenover et al. (29) and differed from PFGE patterns previously identified among ST22-MRSA-IV isolates by ≥7 PFGE bands. Using these criteria, a total of 1,663 pvl-negative sporadic MRSA isolates were identified by the NMRSARL from patients in Irish hospitals between 2000 and 2012. Of the 1,663 isolates, 841 were investigated and determined to be pvl negative either by PCR, as described previously (30), or using an in-house real-time PCR assay. The remaining 822 isolates were not investigated for pvl, as they yielded AR and/or PFGE typing patterns indicative of strains not previously associated with pvl, e.g., AR13 and AR14, and therefore a pvl-negative status was inferred for these (30, 31). All pvl-positive isolates recovered in Ireland during the study period between 2000 and 2012 were investigated as part of a separate study (28). Eighty-seven of the 1,663 pvl-negative sporadic MRSA isolates, representative of approximately 5% of sporadic pvl-negative MRSA isolates identified each year from patients in Irish hospitals during the 12-year study period (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and representing as diverse a range as possible of AR and/or PFGE typing patterns, were selected for detailed investigation. In addition, one pvl-negative MRSA isolate recovered from a patient in the community but who had previously been hospitalized on several occasions was also included for investigation. This isolate harbored mecC (SCCmec type XI) and was included because this clone was recovered sporadically in two patients in two separate hospitals in Ireland in 2010 (2) and has recently been reported in several other European countries (32). The majority of the MRSA isolates (73.8% [65/88]) selected for study were recovered from infections (89% [58/65] BSIs and 10.8% [7/65] skin and soft tissue infections [SSTIs]), 11% (10/88) were colonizing isolates from patient screening, and no information was available for the remainder (14.8% [13/88]). Isolates were identified as S. aureus, and methicillin resistance was confirmed as described previously (30). Isolates were stored on Protect beads (Technical Service Consultants Limited, Heywood, United Kingdom) at −70°C prior to subsequent detailed analysis.

DNA microarray analysis.

The 88 sporadic MRSA isolates were investigated by DNA microarray profiling using the StaphyType kit (Alere Technologies GmbH, Jena, Germany). The StaphyType kit consists of individual DNA microarrays mounted in 8-well microtiter strips which detect 333 S. aureus gene sequences and alleles, including species-specific, antimicrobial resistance and virulence-associated genes, SCCmec genes, typing markers, and a staining control (33, 34). ArrayMate software (version 2012-01-18) (Alere Technologies) was used to analyze data generated by the microarray system and to assign isolates to inferred sequence types (STs) and/or clonal complexes (CCs) by comparing the DNA microarray profile results of test isolates to microarray profiles of an extensive range of reference strains held in the ArrayMate database that have been previously typed by MLST (33, 34). The DNA array can assign all isolates investigated to the correct MLST clonal complex (CC) with a 98% correlation with STs assigned by MLST (21). Genomic DNA for use with the DNA microarray was extracted from all isolates by enzymatic lysis using the buffers and solutions provided with the StaphyType kit and the Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Crawley, West Sussex, United Kingdom). The primers, probes, and protocols for this DNA microarray system have been described in detail previously (34).

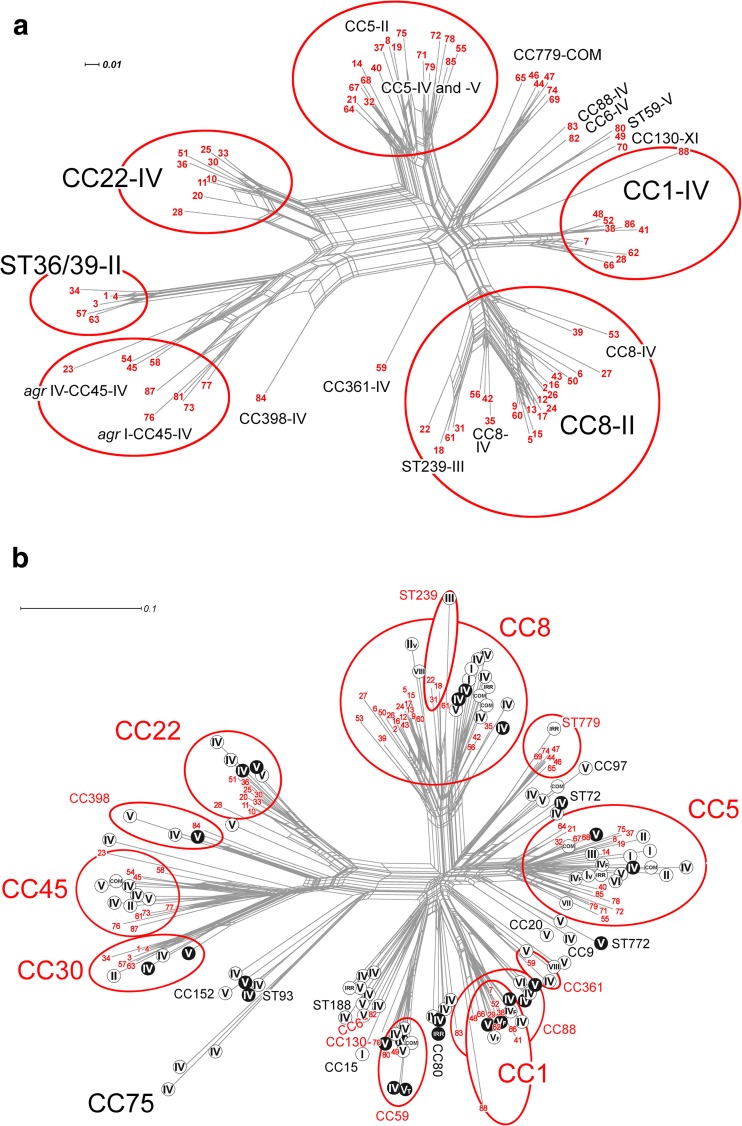

In order to visualize the similarities between the 88 sporadic isolates investigated (although not necessarily true phylogenetic relationships), a network tree was constructed using the complete DNA microarray hybridization profile data of the isolates using the software program SplitsTree, version 4.11.3 (35), as described previously (1). Array hybridization profiles of the isolates were converted into a series of strings of letters that can be handled by the software as sequences. For comparison, array profiles of 3,139 MRSA isolates representative of MRSA isolates globally that were characterized in a previous study were included for comparison (1).

Molecular typing.

Genomic DNA for spa typing, MLST, and SCCmec typing was extracted from each isolate using enzymatic lysis and the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Unless otherwise stated, PCRs were performed using GoTaq Flexi DNA polymerase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions and using the published methods for each PCR protocol as described below. PCR amplifications were performed in a G-storm GS1 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR products were visualized by conventional agarose gel electrophoresis and purified with the GenElute PCR cleanup kit (Sigma-Aldrich Ireland Ltd., Arklow, County Wicklow, Ireland).

All isolates underwent spa typing using the primers and thermal cycling conditions described by the European Network of Laboratories for Sequence Based Typing of Microbial Pathogens (SeqNet [http://www.seqnet.org]). Sequencing was performed commercially by Geneservice Limited (Source Bioscience, Dublin, Ireland) using an ABI 3730xl Sanger sequencing platform. Sequences were analyzed and were assigned to spa types using the Ridom StaphType software program, version 1.3 (Ridom GmbH, Wuerzburg, Germany) (36).

Although all isolates were assigned to STs and/or CCs using the DNA microarray, this system became available only during the latter half of the study. Prior to 2006, MLST had been performed on a subset of sporadic MRSA isolates (n = 27) representative of different spa types (Table 1). MLST was performed as described previously (37), sequences were analyzed using BioNumerics software, version 7.1 (Applied Maths, Ghent, Belgium), and alleles and STs were assigned using the MLST database (http://www.mlst.net/).

TABLE 1

Molecular characteristics of 88 sporadic MRSA isolates recovered from patients in Irish hospitals between 2000 and 2012

| Isolate reference number(s)a | CC/ST-spa type | SCCmec type/description (n) | agr type | Capsule type | IEC type (n)b | Antimicrobial resistance genes (n) | Virulence genes (n) | Locations where similar isolates have been reported (reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52, 88 | CC/ST1-t2279 | IVa (2) | III | 8 | D (1), E (1) | blaZ (2), fusC (1), sdrM (2) | sea (1), sek (2), seq (2), seh (2) | Western Australia (1) |

| 62, 86 | CC1-t2279c | IVa and SCCfus (2) | III | 8 | D | blaZ (2), fusC (2), sdrM (2) | sea (2), sek (2), seq (2), seh (2) | Malta (68) |

| 48 | CC1-t386 | IVa (1) | III | 8 | E | blaZ, erm(C), aphA3, sat, sdrM | seh | Germany (1) |

| 7 | CC1-t127 | IVa (1) | III | 8 | D | blaZ, sdrM | sea (1), sek, seq, seh | Western Australia (1) |

| 38, 41 | CC1-t127 | IVa and SCCfus (2) | III | 8 | D | blaZ (2), erm(A) (2), fusC (2), sdrM (2) | sea (2), sek (2), seq (2), seh (2) | Malta (68) |

| 29 | CC1/ST1336-t127c | IVc (1) | III | 8 | D | blaZ, tet(K), sdrM | sea, seb, sek, seq, seh | None |

| 66 | CC1/ST1115-t127c | IVa (1) | III | 8 | E | blaZ, erm(C), aphA3, sat, tet(K), sdrM | seh | None |

| 8, 19 | CC/ST5-t045 | II (2) | II | 5 | D (1), nege (1) | blaZ (2), erm(A) (2), aadD (2), sdrM (2), fosB (2), qac(A) (1) | tst (2), sea (1), egc (2), sed (1), sej (1), ser (1) | None |

| 32, 68 | CC/ST5-t242c | VT (2) | II | 5 | B | blaZ (2), aacA-aphD (2), sdrM (2), fosB (2) | egc (2) | USA (69) |

| 85 | CC5-t002 | VT (harboring ccrC2) (1) | II | 5 | G | blaZ, aacA-aphD, sdrM, fosB | egc, sep, sed, sej, ser | None |

| 75 | CC5-t002 | II (1) | II | 5 | F | erm(A), aacA-aphD, aadD, mupA, sdrM, fosB, qac(C) | egc, sep | Pandemic (1) |

| 72 | CC5-t002 | IVc (1) | II | 5 | F | blaZ, sdrM, fosB | egc, sep, sed, sej, ser | Denmark (38) |

| 79 | CC5-t002 | IV (nonsubtypeable) (1) | II | 5 | F | blaZ, sdrM, fosB | egc, sep | Pandemic (1) |

| 64 | CC5/ST930c,d-t002b | IV (nonsubtypeable) (1) | II | 5 | B | blaZ, erm(C), aacA-aphD, sdrM, fosB | egc | None |

| 21 | CC5/ST100-t002c,d | Novel 1 (mecA only detected) (1) | II | 5 | E | blaZ, aacA-aphD, sdrM, fosB | egc | None |

| 71 | CC5-t067 | IV (nonsubtypeable) & ccrB4 (1) | II | 5 | F | blaZ, msrA, mph(C), aacA-aphD, aadD, aphA3, sat, mupA, sdrM, fosB, qac(C) | egc, sep | Spain (70) |

| 55 | CC5-t088 | VT (1) | II | 5 | D | erm(C), sdrM, fosB | sea, egc, sed, sej, ser | None |

| 14 | CC/ST5-t109c,d | I and ccrC (1) | II | 5 | B | blaZ, erm(A), aacA-aphD, aphA3, sat, tet(K), sdr(M), fosB, qac(A) | egc | None |

| 67 | CC5/ST1435d-t242c | VT (1) | II | 5 | B | blaZ, aacA-aphD, sdrM,fosB | egc | None |

| 78 | CC5-t442 | V (harboring ccrC8) (1) | II | 5 | E | blaZ, aacA-aphD, sdrM, fosB | egc, sed, sej, ser | Australia (71) |

| 37 | CC/ST5-t463 | II (1) | II | 5 | A | blaZ, erm(A), aadD, sdrM, fosB | tst, sea, egc, sed, sej, ser | None |

| 40 | CC5-t1781 | IVa (1) | II | 5 | G | blaZ, msrA, mph(C), aphA3, sat, sdrM, fosB, qac(C) | egc, sep, sej, ser | Germany, Canada (spa.ridom.de) |

| 82 | CC6-t701 | IVh (1) | I | 8 | E | blaZ, sdrM, fosB | neg | Australia, Abu Dhabi, Hong Kong (72) |

| 2, 6, 9, 13, 17, 24, 27, 50, 15, 16 | CC/ST8-t190 | IID and SCCM1 (10) | I | 5 | D (8), neg (2) | blaZ (10), erm(A) (10), aacA-aphD (10), aadD (1), aphA3 (4), sat (4), fusB (1), tet(K) (1), sdrM (10), cat (1), fosB (10), qacA (9) | sea (8), neg (2) | None |

| 5, 12, 60, 43 | CC/ST8-t190 | IIE and SCCM1 (4) | I | 5 | D (3), neg (1) | blaZ (4), erm(A) (4), aacA-aphD (4), aadD (1), aphA3 (3), sat (3), mupA (1), sdrM (4), fosB (4), qacA (4) | sea (3), neg (1) | None |

| 26 | CC/ST8-t190c | IID (1) | I | 5 | A | erm(A), aacA-aphD, aphA3, sat, sdrM, fosB | tst, sea | None |

| 56 | CC/ST8-t190c | VI (1) | I | 5 | E | blaZ, erm(A), aphA3, sat, sdrM, fosB | neg (1) | None |

| 39, 53 | CC8-t008 | IVa (2) | I | 5 | B (1), neg (1) | blaZ (2), erm(A) (1), msrA (1), mph(C) (1), aphA3 (1), sat (1), sdrM (2), fosB (2) | ACME-arc (2) | USA (1) |

| 42 | CC/ST8-t064c | IVa (1) | Ì | 5 | E | blaZ, erm(C), sdrM, fosB | seb, sek, seq | USA, Switzerland (73, 74) |

| 35 | CC/ST8-t4268 | IVd (1) | I | 5 | D | blaZ, erm(C), aacA-aphD, dfrS1, tet(M), sdrM, fosB, qac(A), qac(C) | sea, neg | None |

| 61 | CC/ST8-t1209c | IIIB (1) | I | 8 | neg | blaZ, erm(A), aacA-aphD, aadD, tet(M), sdrM, fosB, qac(A) | sek, seq | None |

| 31 | CC8/ST239-t030c | IIIB (1) | I | 8 | neg | blaZ, erm(A), tet(M), sdrM, fosB, qac(A) | sek, seq | Pandemic (75) |

| 22 | CC8/ST239-t037 | IIIA (1) | I | 8 | D | blaZ, erm(A), aacA-aphD, aphA3, sat, tet(M), sdrM, fosB, qac(A) | sea, sek, seq | Pandemic (1) |

| 18 | CC8/ST239-t037c | III and SCChg (1) | I | 8 | D | blaZ, erm(A), aacA-aphD, tet(K), tet(M), sdrM, aphA3, sat, fosB, qac(A) | sea, sek, seq | Pandemic (1) |

| 11, 20, 25, 10, 28 | CC/ST22-t032c | IVh (5) | I | 5 | B (3), neg (2) | blaZ (5), erm(C) (4), aphA3 (1), sat (1), qac(A) (1) | egc (4), sec (2), sel (2) | Pandemic (1) |

| 33 | CC/ST22-t032c | IVg (1) | I | 5 | B | blaZ, erm(C) | egc, sec, sel | Pandemic (1) |

| 30 | CC/ST22-t022c | IVh (1) | I | 5 | B | blaZ, erm(C) | egc, sec, sel | Pandemic (1) |

| 36 | CC/ST22-t2951 | IVh (1) | I | 5 | B | blaZ, erm(C), lnu (A), aacA-aphD, aadD, mupA, cat, fosB, qac(C) | egc | None |

| 51 | CC22-t1802 | IVh (1) | I | 5 | B | blaZ, erm(C), fosB | egc, sed | None |

| 57, 1, 3, 4 | CC/ST36-t018c | II (4) | III | 8 | A (4) | blaZ (4), erm(A) (4), aadD (2), sdrM (4), fosB (4) | tst (3), sea (4), sed (1), egc (4) | UK (76) |

| 63 | CC/ST36-t018c | II and ccrC (1) | III | 5 | A | blaZ, erm(A), aacA-aphD, aadD, sdrM, fosB | tst, sea, egc | None |

| 34 | CC30/ST36-t012 | II (1) | III | 5 | B | blaZ, erm(A), aacA-aphD, aadD, mupA, sdrM, fosB | tst, egc | UK (76) |

| 23, 45, 54, 87 | CC/ST45-t727 | IVa (4) | IV | 8 | B (2), neg (2) | blaZ (4), erm(C) (2), fusB (4), mupA (1), tet(M) (2), sdrM (4), fosB (1) | egc (4) | Hong Kong, Australia (1) |

| 58 | CC/ST45-t727c | Novel 2 (mecA only detected) (1) | IV | 8 | neg | blaZ, sdrM | egc | None |

| 77 | CC/ST45-t132 | IVa (1) | I | 8 | B | blaZ, sdrM | egc | Germany, Belgium (1) |

| 73 | CC/ST45-t026 | IVa (1) | I | 8 | B | blaZ, erm(C), sdrM | egc, sec, sel | Germany, Belgium (1) |

| 81 | CC/ST45-t065 | IVa (1) | I | 8 | B | blaZ, erm(A), sdrM | egc | Germany, Belgium (1) |

| 76 | CC/ST45-t015 | IVc (1) | I | 8 | B | blaZ, aadD, sdrM | egc, sec, sel | Germany, Belgium (1) |

| 43, 80 | CC/ST59-t316c | V (harboring ccrC8) (2) | I | 8 | B | blaZ (2), msrA (2), fusB (2), mupA (2), sdrM (2) | seb (2), sek (2), seq (2) | Australia, Taiwan (1) |

| 83 | CC88/ST88-t186 | IVa (1) | III | 8 | E | blaZ, erm(A), sdrM | sec, sel | Australia, Japan (1, 57) |

| 70 | CC130-t12399 | XI (1) | III | 8 | neg | sdrM | neg | Europe, UK (32) |

| 59 | CC/ST361-t315c | IVg (1) | I | 8 | B | blaZ, aacA-aphD, aphA3, sat, tet(K), sdrM, fosB | egc | Western Australia (32) |

| 84 | CC/ST398-t011 | IVa (1) | I | 5 | neg | blaZ, aacA-aphD, tet(M), sdrM | neg | Hong Kong, Belgium, Germany (1) |

| 65, 69, 74, 44, 46, 47 | CC/ST779-t878 | ψSCCmec-SCC-SCCCRISPR (6) | III | 5 | B | blaZ (6), aadD (1), fusC (6), mupA (1), sdrM (6) | etD (6), edinB (6), seb (1), sed (1), sej (1), ser (1) | Uk, Ireland, France, Australia (1, 6) |

Fifty-two sporadic MRSA isolates underwent additional PCR-based SCCmec typing to distinguish between SCCmec types and subtypes when the DNA microarray was unable to further differentiate them. This included (i) SCCmec IV subtyping using the method previously described by Milheirico et al. (38), (ii) SCCmec IIA and IIB differentiation using a novel primer, Tn554r (5′-GATAGCAGTATGCCTTAATG-3′), targeting Tn554, which is present only in SCCmec IIA, and a previously described ccrAB2 forward primer (α2) (39), (iii) SCCmec IIIA and IIIB differentiation using a multiplex PCR previously described by Oliveira and de Lencastre (40), and (iv) ccrC allotype identification using a previously described multiplex PCR to differentiate between SCCmec types V (ccrC2) and VT (ccrC2 and ccrC8) (41). In addition, two isolates harboring potentially novel SCCmec types were also further investigated using two previously described multiplex PCR schemes targeting the mec class and the ccr gene complexes (39). Finally, one isolate underwent PCR to confirm the presence of mecC and long-range PCR to confirm the presence of SCCmec XI using previously described primers (2). Long-range PCRs were performed using the Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche Diagnostics GmdH, Lewes, East Sussex, United Kingdom). The following MRSA control reference strains and clinical isolates were used as positive controls for SCCmec typing: AR07.4/0237 (SCCmec IIA/B) (20), E0898 (SCCmec III) (20), CA05 (SCCmec IVa) (42), 8/63-P (SCCmec IVb) (42), JCSC/4788 (SCCmec IVc) (43), JCSC/4469 (SCCmec IVd) (44), M04/0177 (SCCmec IVg) (17), E1749 (SCCmec IVh) (17), WIS (SCCmec V) (45), PM1 (SCCmec VT) (41), and M10/0061 (SCCmec XI) (2).

RESULTS

Genotyping.

Fifty-four different combinations of MLST CC/ST, spa types, and SCCmec types were identified among the 88 isolates, 41 of which were each represented by just one isolate (Table 1). The most prevalent type combination was CC8/ST8-t190-MRSA-IID and SCCM1 (11.4% [10/88]), followed by CC779/ST779-t878-MRSA-ψSCCmec-SCC-SCCCRISPR (6.8% [6/88]) and CC22/ST22-t032-MRSA-IVh (5.7% [5/88]). Three type combinations occurred in 4.5% (4/88) of isolates, including CC8/ST8-t190-MRSA-IIE and SCCM1, CC30/ST36-t018-MRSA-II, and CC45/ST45-t727-MRSA-IVa. Seven type combinations occurred in 2.3% (2/88) of isolates each, including the combination CC1-t127-MRSA-IVa and SCCfus and the combinations ST1-t2279-MRSA-IVa and SCCfus, CC1-t2279-MRSA-IVa, ST5-t045-MRSA-II, ST5-t242-MRSA-VT, CC8/ST8-t008-MRSA-IVa, and ST59-t316-MRSA-V (harboring ccrC8) (Table 1). A total of 37 spa types and 13 MLST-CCs were identified (Table 1). The identification of STs using MLST or the DNA microarray or both was possible for 63/88 isolates, resulting in 17 STs, 4 of which were novel (Table 1). Overall, isolates belonging to CC8 predominated (24/88 [27.3%]), followed by isolates belonging to CC5 (17/88 [19.3%]), CC1 (10/88 [11.4%]), CC22 (9/88 [10.2%]), CC45 (9/88 [10.2%]), CC779 (6/88 [6.8%]), CC30 (6/88 [6.8%]), and CC59 (2/88 [2.3%]). The remaining CCs (6, 78, 398, 361, and 130) were each represented by one isolate (Table 1).

A total of 25 SCCmec types and subtypes were identified, including SCCmec IVa (20.5% [18/88]), which was the most prevalent, followed by SCCmec IID and SCCM1 (11.4% [10/88]), SCCmec II (10.2% [9/88]), SCCmec IVh (10.2% [9/88]), ψSCCmec-SCC-SCCcrispr (6.8% [6/88]), SCCmec IIE and SCCM1, SCCmec VT, and SCCmec IVa and SCCfus (4.5% [4/88]), SCCmec IVc (3.4% [3/88]), and SCCmec IIIB and SCCmec IVg (2.3% [2/88]); six SCCmec types were detected in just one isolate, including SCCmec types IID and III, SCChg IIIA, and SCCmec IVd, VI, and XI (Table 1).

Two isolates (CC5/ST100-t002 and CC45/ST45-t747) carried possible novel SCCmec elements, because mecA was identified, but no ccr gene could be detected by the DNA microarray or by PCR-based SCCmec typing (Table 1). The remaining nine isolates harbored six possible novel SCCmec subtypes (10.2% [9/88]). Of these, three isolates harbored SCCmec elements assigned to previously described SCCmec types, but additional ccr genes were also identified, i.e., SCCmec I and ccrC (ST5-t109), SCCmec II and ccrC (ST36-t018), and SCCmec IV (nonsubtypeable) and ccrB4 (CC5-t067) (Table 1); two isolates (CC5-t002 and ST930-t002) harbored SCCmec IV elements that could not be subtyped (Table 1).

Two novel SCCmec V or VT variants were identified in four isolates due to the carriage of a class C mec complex but unusual combinations of ccr genes. The SCCmec V or VT elements described in the literature to date have been described as harboring class C mec and (i) ccrC allele ccrC1 in SCCmec V (5C) in MRSA strain WIS (45), (ii) ccrC8 and ccrC10 in SCCmec V (5C2&5) in MRSA strain UMCG-M4 (46), or (iii) ccrC2 and ccrC8 in SCCmec VT (5C2&5) in MRSA strain PM1 (41, 47). However, four isolates in the present study carried class C mec, but one harbored ccrC2 only (CC5-t002) and three isolates carried ccrC8 only (CC5-t442 and two ST59-t316) (Table 1).

Overall, SCCmec IV types and subtypes predominated and accounted for 45.5% (40/88) of isolates, followed by SCCmec II (29.5% [26/88]), SCCmec V (9% [8/88]), pseudo element ψSCCmec-SCC-SCCcrispr (6.8% [6/88]), and SCCmec III (3.4% [3/88]) (Table 1). The majority of isolates carried mecA, with just one isolate (CC130-t12399) carrying mecC.

Virulence-associated genes.

Immune evasion cluster (IEC) genes were detected among 84.1% (74/88) of sporadic MRSA isolates and included scn (84% [74/88]), sak (84% [74/88]), chp (44.3% [39/88]), sea (34.1% [30/88]), and sep (6.8% [6/88]) (Table 1). The most common IEC type as defined by Van Wamel et al. was IEC type B (34.1% [30/88]), followed by D (28.4% [25/88]), E (9.1% [8/88]), A (6.8% [6/88]), F (4.5% [4/88]), and G (1.1% [1/88]) (Table 1) (48). Clonal complex 5 exhibited the most IEC types, including IEC types A, B, and D to G, while CC22, CC45, CC59, and CC779 harbored IEC type B only. CC1, CC8, and CC30 harbored multiple IEC types, and all CC8 MRSA isolates harboring SCCmec IID plus SCCM1 and SCCmec IIE plus SCCM1 elements that harbored IEC genes exhibited IEC type D, and this association has been reported previously (Table 1) (21). The accessory gene regulator (agr) allele I was the most dominant agr type (47.7% [42/88]), followed by agr III (27.3% [24/88]), agr II (19.3% [17/88]), and agr IV (6.8% [6/88]) (Table 1). The capsule gene type 5 predominated and was detected in 60.2% (53/88) of isolates (Table 1).

The virulence-associated genes detected among the isolates belonging to the different CCs are shown in Table 1. The most common toxin genes detected were the enterotoxin gene cluster (egc), which was detected in 48.9% (43/88) of sporadic isolates belonging to six CCs, and the enterotoxin A gene sea, which was detected in 34.1% (30/88) belonging to four CCs (1, 5, 8, and 30). The enterotoxin genes sek and seq were harbored by 16% (14/88) of isolates (CC1, -8, and -59), and 11.4% (10/88) of isolates (all CC1) harbored the enterotoxin gene seh. The toxic shock toxin gene tst was detected in 9% (8/88) of isolates, all of which belonged to CC30 (83.3% [/6]) or CC5 (15.8% [3/19]). The enterotoxin genes sec and sel were harbored by 7.9% (7/88) of isolates from three CCs (22, 45, and 78), and seb was detected in 4.5% (4/88) of isolates from three CCs (1, 8, and 59). Various combinations of the enterotoxin genes sed, sej, and ser were detected in 11.4% (10/88) of isolates (CC5, ST30, CC22, and CC779). The ACME-arc genes were detected in 2.3% (2/88) of isolates (both ST8-MRSA-IVa). The exfoliative toxin gene etD and the epidermal cell differentiation inhibitor gene, edinB, were detected among all ST779-MRSA isolates (6.8% [6/88]), and the sep enterotoxin gene was detected in 6.8% (6/88) of isolates in one CC (CC5).

Antimicrobial resistance genes.

The antimicrobial resistance genes detected among the isolates belonging to the different CCs are shown in Table 1. The most prevalent antimicrobial resistance genes detected among the 88 sporadic MRSA isolates other than mec were the beta-lactamase resistance gene blaZ (96.6% [84/88 isolates]) and sdrM, encoding an unspecific efflux pump (89.8% [79/88]). The erm(A) gene (encoding resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramin B compounds) was detected in 40.9% of isolates (36/88) belonging to 6/13 CCs (CC1, -5, -8, -30, and -45 and ST88). The aminoglycoside resistance gene aacA-aphD (encoding resistance to amikacin, gentamicin, kanamycin, and tobramycin) was detected in 39.8% of isolates (35/88) in 6/13 CCs (CC5, -8, -22, and -30, ST361, and ST398). Other significant antimicrobial resistance genes detected included the fusidic acid resistance genes fusB and fusC, which were detected in 7.9% (7/88) and 11.4% (11/88) of isolates, respectively. The fusB gene was detected in three CCs (8, 45, and 59), and the fusC gene was detected in two CCs (1 and 779). The mupirocin resistance gene, mupA, was present in 10.2% of isolates (9/88) belonging to seven different CCs (5, 8, 22, 30, 45, 59, and 779).

Two or more resistance genes that encoded resistance to commonly used antimicrobial agents, including aminoglycosides, macrolides-lincosamides, tetracycline, fusidic acid, and mupirocin, were detected among 55.7% (49/88) of isolates and included isolates from all CCs except for the CCs represented by one isolate only (6, 78, 398, 361, and 130) (Table 1).

Similarities between sporadic and global isolates based on microarray data.

Figure 1a shows a graphic representation of the diversity detected among the 88 sporadic MRSA isolates based on DNA microarray profiles. SplitsTree analysis using the transformed microarray profile data separated all 88 isolates into their MLST CCs, and within each CC, similar isolates were grouped closely together. For example, two closely related ACME-arc-positive ST8-MRSA-IVa isolates (isolates 39 and 53) (Table 1) clustered together and were separate from a more distantly related ACME-arc-negative ST8-MRSA-IVd isolate (isolate 35) (Table 1). Figure 1b shows a graphic representation of the relationships between the 88 sporadic MRSA isolates based on array profile data relative to a very large population of global MRSA isolates (n = 3,139). Within the 88 sporadic MRSA isolate population, isolates with specific CCs distributed among global isolates with the same CC in each case (Fig. 1b).

Network trees generated using the SplitsTree, version 4.11.3, software program (1, 35) and the StaphyType DNA microarray profiles as described previously (1) to visualize the similarities and relationships between CCs and mobile genetic elements, including SCCmec, for the 88 sporadic MRSA isolates investigated and a global population of MRSA isolates. (a) Network tree showing the relationships between the 88 sporadic MRSA isolates investigated. (b) Network tree showing the relationships between the 88 sporadic MRSA isolates investigated in the present study and a previously described global collection of MRSA isolates (n = 3,139) (1). Each sporadic MRSA isolate investigated in the present study is indicated with a number in red (numbers 1 to 88); the details of isolates represented by each number are listed in Table 1. The major CCs identified among isolates in the current study and the previous global study are circled in red, and Roman numerals indicate SCCmec types. In panel b, CCs and STs that were exhibited by MRSA strains from this study are shown in red, and if a CC or ST was not exhibited by any of the 88 sporadic MRSA strains, it is shown in black. MRSA strains from the previously described global population (1) that lacked the Panton-Valentine leukocidin toxin genes lukF/S-PV (pvl) are indicated using black letters on a white background, and pvl-positive MRSA strains are indicated using white letters on a black background. The scale bars show how the length of a branch translates in sequence divergence. The unit is divergent nucleotides divided by the length of the sequence analyzed. Abbreviations: IRR, irregular SCCmec elements; COM, composite or multiple SCCmec elements.

DISCUSSION

Many detailed investigations of the predominant nosocomial MRSA clones prevalent in different regions of the world have been reported, whereas in-depth systematic investigations of sporadically occurring MRSA clones are scarce. The highly clonal ST22-MRSA-IV strain continues to predominate in Irish hospitals, but the prevalence of sporadically occurring MRSA from BSIs increased 2-fold between 2005 and 2011 (19). This study is the first to investigate in detail the molecular epidemiology of sporadic MRSA isolates in Irish hospitals, and it has revealed extensive diversity in genetic backgrounds, SCCmec elements, and virulence and resistance genes. Comparative analysis of DNA microarray data from the 88 sporadic isolates investigated and the corresponding data from 3,139 global MRSA isolates revealed that the relationships between the sporadic MRSA isolates from patients in Irish hospitals reflects the relationships between global MRSA isolates (Fig. 1). An apparently reduced diversity of SCCmec elements in the 88 sporadic MRSA isolates compared to the global MRSA population likely reflects the reduced biodiversity associated with a restricted/insular geographic location (Fig. 1).

A total of 54 MLST, spa, and SCCmec type combinations were identified among the 88 sporadic MRSA isolates investigated, with 49 isolates (55.7%) carrying genes encoding resistance to two or more commonly used antimicrobial agents and 40 (38.6%) harboring two or more virulence-associated genes previously reported to be located on MGEs. Isolates belonging to CC8/ST8-t190-IID/IIE ± SCCM1 predominated. Previous studies have demonstrated a reduced fitness associated with larger SCCmec elements (49, 50), and we previously speculated that the potential fitness cost associated with carrying a large SCCmec-SCC composite island (CI) may have contributed to the decline of ST8-MRSA-IIA-IIE and SCCM1 (21) in Irish hospitals. However, the many resistance genes detected among isolates of this clone may also have contributed to its decline due to reduced fitness, but other lineage-specific factors may also have contributed (51).

The second most prevalent clone, ST779-t878-MRSA-ψSCCmec-SCC-SCCcrispr, also carried multiple resistance genes and a large SCC-CI element that may have originated in coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS). We recently reported the emergence of this clone in Irish hospitals (6), and ST779-MRSA has also been reported sporadically in Australia, Canada, Germany, Malaysia, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom (http://saureus.mlst.net/) (2, 6, 24, 52). Fitness costs associated with the carriage of a large SCC-CI and multiple MGE-located resistance genes may curtail the widespread emergence of this clone in the absence of selective pressure.

Extensive diversity was detected among the SCCmec elements harbored by the sporadic MRSA isolates and included 25 different SCCmec types and subtypes encompassing types and/or subtypes of SCCmec types I to VI, SCCmec type XI, two possible novel SCCmec elements, and six possible novel SCCmec subtypes. SCCmec type IV predominated, accounting for almost half of the isolates. Since SCCmec IV is also the SCCmec type of the ST22-MRSA-IV clone endemic in Irish hospitals for the last decade (17), it is clear that SCCmec IV is the dominant SCCmec element among all nosocomial MRSA isolates in Ireland. However, eight different subtypes were identified among the sporadic isolates, with SCCmec IVa being the most common (20.5% [18/40]). In contrast, SCCmec IVh predominates among isolates of the endemic ST22-MRSA-IV clone (17). It is not possible to discriminate between most SCCmec IV subtypes using the DNA microarray, and considering that these are associated with particular pandemic MRSA clones, e.g., SCCmec IVh in ST22 and SCCmec IVa in ST8/USA300, it is essential that detailed SCCmec IV subtyping be performed to ensure effective tracking and typing of these clones.

SCCmec V and VT subtyping identified novel SCCmec V subtypes and provided further evidence of the diversity present in SCCmec V elements (46), including ccrC alleles. The CC59-MRSA-V clone usually harbors two ccrC1 complexes (ccrC1 allele 2 and ccrC allele 8) (47). However, the two CC59-MRSA-V isolates and a CC5-t442-MRSA isolate identified in the study harbored only ccrC1 allele 8. Additionally, a CC5-t002-MRSA isolate harbored an SCCmec V element with just one ccrC allotype, ccrC2. These may represent possible SCCmec V variants or precursors in two separate CCs, CC5 and CC59.

The majority of isolates investigated had genotypes generally considered to be health care associated, including ST8-MRSA-IID/IIE ± SCCM1, ST239-MRSA-III, ST36-MRSA-II, ST22-MRSA-IV, ST45-MRSA-IV, ST5-MRSA-II, and ST361-t315-MRSA-IVg (1, 53), each of which, apart from the ST361 MRSA-IVg isolate, was previously identified in Ireland as either predominant or sporadic strains (2, 20). Many of these clones predominate or have predominated in hospitals in other countries, and no major differences were noted between these isolates and those reported previously (1). A number of isolates with CC/ST and SCCmec type combinations commonly associated with pvl-positive community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) clones were also detected, including CC1-MRSA-IV (1, 54), CC59-MRSA-V (47, 55), ST8-t008-MRSA-IVa (1), CC5-MRSA-IV (1), CC5-MRSA-V (56), and CC88/ST88-t186-MRSA-IVa (1, 57). It should be noted that potential CA-MRSA-associated clones may be underrepresented in the present study due to the exclusion of pvl-positive sporadic MRSA isolates. The prevalence of CA-MRSA (both pvl positive and negative) among patients in Irish hospitals remains to be determined.

This study also found further evidence of the possible zoonotic spread of MRSA in Ireland. First, a CC130-MRSA-XI isolate recovered in 2007 was identified. We previously reported the recovery in 2010 of two sporadic CC130-MRSA-XI isolates from separate hospitals (2). The newly identified isolate exhibited a previously unreported spa type (t12399) harboring two additional spa repeats compared to spa type t843 exhibited by the CC130 MRSA isolates recovered in 2010 (2). The isolate was recovered from an elderly patient in the community who had previously been hospitalized on several occasions and who lived adjacent to a farm. Since its first detection, SCCmec XI has been reported sporadically among MRSA isolates belonging to a number of animal-associated MRSA lineages (predominantly CC130) in many different European countries from human and animal sources (32), and several studies have provided evidence for the zoonotic spread of these strains (58, 59). Other clones of possible animal origin were also identified, all recovered between 2007 and 2011, including the equine-associated ST8-t064-MRSA-IVa clone (60, 61), as well as the livestock-associated clone ST398-t011-MRSA-IVa and CC6-MRSA-IVh, which has been linked with camels (1, 62, 63). These findings highlight the importance of animals as a reservoir for MRSA and for effective surveillance to minimize the spread of these clones in hospitals.

The prevalence and diversity of resistance and virulence genes identified among the sporadic MRSA isolates also highlight the extensive reservoir of these genes that exist within the population of Irish MRSA. This, coupled with the range of genetic backgrounds of the isolates, highlights the potential for spread of these resistance genes and thus our ability to treat MRSA colonization and infection. For example, a high rate of the carriage of macrolide (57.9%) and aminoglycoside (43.4%) resistance genes was observed among isolates belonging to an extensive range of genetic backgrounds. Additionally, the high-level mupirocin resistance gene mupA, known to be carried on conjugative plasmids (64), was identified in 9/88 (10.2%) isolates belonging to seven different genetic backgrounds. Mupirocin is commonly used for MRSA nasal decolonization, and previous reports from Ireland have reported high-level mupirocin resistance rates among MRSA isolates from BSIs, ranging from 1.4% between 1999 and 2005 to 3.1% in 2011, predominantly among ST22-MRSA-IV and ST8-MRSA-IIA-IIE isolates (19). Lastly, in Ireland the rate of phenotypic fusidic acid resistance among MRSA isolates from BSIs increased from <10% to 34% between 1999 and 2011 (19). In the present study, 18/88 (20.5%) sporadic isolates harbored either the plasmid-located fusB gene or the SCC-associated fusC gene. More stringent use of these antimicrobial agents is warranted so that resistance does not become more widespread.

Few studies focused primarily on the detailed characterization of sporadic MRSA isolates. The main emphasis of most studies that reported such isolates concentrated on identifying the main MRSA lineages present in large populations of MRSA isolates from particular countries or from several hospitals (20, 65, 66). For example, while reporting the clonal replacement of CC5/ST228-MRSA-I and CC5-MRSA-II by the emerging CC22-MRSA-IV and CC45-MRSA-IV clones as the predominant nosocomial strains over an 11-year period in a German tertiary care hospital, Albrecht et al. also identified 17 pvl-negative sporadic MRSA isolates among 778 isolates investigated, including CC7-MRSA-IV, CC97-MRSA-IV, CC88-MRSA-IV, and CC30/ST36-MRSA-II (67), the former two of which were also identified in the present study. The diversity identified among the Irish sporadic MRSA isolates investigated in this study spans most of the lineages seen at the global level (Fig. 1). This may be because the strains, or at least some of them, have at some stage been endemic in Ireland since their evolutionary origin. However, it is important to emphasize that the origin of some MRSA strains can be polyphyletic resulting from multiple transmissions of identical or similar SCCmec elements from MRSA or CoNS into methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) of one clonal lineage (1). Recurrent importation of MRSA strains from other countries is also likely to have been another significant factor contributing to the diversity found among the sporadic MRSA isolates. The latter suggestion is reflected by the findings of a recent study from this laboratory on pvl-positive MRSA recovered in Ireland over the last decade that revealed frequent importation of MRSA strains, particularly in recent years (28). While the increasing prevalence of sporadic MRSA strains in Ireland may be due to an increase in their importation or to the local emergence of strains, the decreasing prevalence of ST22-MRSA-IV in Irish hospitals may also have contributed, allowing for the emergence of these sporadic MRSA with enhanced virulence and resistance potential. However, further studies of both sporadic and endemic MRSA as well as MSSA are required in order to determine this.

In conclusion, the diversity detected among the 88 representative sporadic MRSA isolates, including SCCmec and SCC-associated elements and virulence-associated and antimicrobial resistance genes, and the number of different genetic lineages identified by MLST, spa typing, and DNA microarray analysis provide further evidence of the need for effective surveillance of this genetically diverse reservoir. Exchange of genetic material between these and other more prevalent MRSA strains may contribute to the emergence of successful MRSA strains in the future. Shore et al. previously demonstrated that there is a history of strain replacement approximately once per decade in Ireland, and therefore, it is important that emerging MRSA strains be detected early (20). The ST22-MRSA-IV clone has predominated for more than a decade in Irish hospitals, and its recent decline in prevalence suggests that a novel strain(s) may emerge in the near future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Microbiology Research Unit, Dublin Dental University Hospital.

We thank the staff of the Irish National MRSA Reference Laboratory, past and present, in particular Angela Rossney, for their ongoing support and collaboration in investigating large collections of MRSA and MSSA isolates. MRSA control isolates were kindly provided by Teuryo Ito, Juntendo University, Japan, and Herminia de Lencastre, Rockfeller University, New York.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 January 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02653-13.

REFERENCES

Articles from Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy are provided here courtesy of American Society for Microbiology (ASM)

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.02653-13

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://aac.asm.org/content/aac/58/4/1907.full.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

The Dissemination and Molecular Characterization of Clonal Complex 361 (CC361) Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Kuwait Hospitals.

Front Microbiol, 12:658772, 06 May 2021

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 34025612 | PMCID: PMC8137340

Epidemiological typing of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus recovered from patients attending a maternity hospital in Ireland 2014-2019.

Infect Prev Pract, 3(1):100124, 24 Jan 2021

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 34368740 | PMCID: PMC8336322

Antimicrobial Resistance and Molecular Characterization of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Slaughtered Pigs and Pork in the Central Region of Thailand.

Antibiotics (Basel), 10(2):206, 19 Feb 2021

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 33669812 | PMCID: PMC7922250

Human mecC-Carrying MRSA: Clinical Implications and Risk Factors.

Microorganisms, 8(10):E1615, 20 Oct 2020

Cited by: 25 articles | PMID: 33092294 | PMCID: PMC7589452

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Equine Methicillin-Resistant Sequence Type 398 Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Harbor Mobile Genetic Elements Promoting Host Adaptation.

Front Microbiol, 9:2516, 24 Oct 2018

Cited by: 17 articles | PMID: 30405574 | PMCID: PMC6207647

Go to all (22) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

DNA microarray profiling of a diverse collection of nosocomial methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus isolates assigns the majority to the correct sequence type and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) type and results in the subsequent identification and characterization of novel SCCmec-SCCM1 composite islands.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 56(10):5340-5355, 06 Aug 2012

Cited by: 21 articles | PMID: 22869569 | PMCID: PMC3457404

Clonal Diversity and Genetic Characteristics of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Japan.

Microb Drug Resist, 25(8):1164-1175, 20 May 2019

Cited by: 18 articles | PMID: 31107152

Genotyping of community-associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) in a tertiary care centre in Mysore, South India: ST2371-SCCmec IV emerges as the major clone.

Infect Genet Evol, 34:230-235, 01 Jun 2015

Cited by: 17 articles | PMID: 26044198

A 6-Year Update on the Diversity of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Clones in Africa: A Systematic Review.

Front Microbiol, 13:860436, 03 May 2022

Cited by: 17 articles | PMID: 35591993 | PMCID: PMC9113548

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

a

a