Abstract

Free full text

Loeys–Dietz syndrome: a primer for diagnosis and management

Associated Data

Abstract

Loeys–Dietz syndrome is a connective tissue disorder predisposing individuals to aortic and arterial aneurysms. Presenting with a wide spectrum of multisystem involvement, medical management for some individuals is complex. This review of literature and expert opinion aims to provide medical guidelines for care of individuals with Loeys–Dietz syndrome.

Genet Med 16 8, 576–587.

Loeys–Dietz syndrome (LDS), an autosomal-dominant connective tissue disorder first characterized by aortic aneurysms and generalized arterial tortuosity, hypertelorism, and bifid/broad uvula or cleft palate, was first described in 2005.1,2 With variable expression, mutations in the transforming growth factor β receptor I (TGFBR1) and transforming growth factor β receptor II (TGFBR2) genes were discovered to be the first reported genetic causes of LDS. Subsequently, gene mutations in the mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 (SMAD3) gene and the transforming growth factor β 2 ligand gene (TGFB2) were associated with phenotypes showing typical manifestations of LDS.3,4,5,6 Mutations in all four genes show similarly altered transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling, and individuals show similar cardiovascular, craniofacial, cutaneous, and skeletal features.1,2,3,4,5,6 Most importantly, affected individuals show widespread arterial involvement, with vascular tortuosity, a high risk of aneurysms and dissections throughout the arterial tree, and an aggressive vascular course. No specific clinical criteria exist, as the diagnosis is confirmed by a molecular test.7 We propose that a mutation in any of these four genes in combination with arterial aneurysm or dissection or family history of documented LDS should be sufficient to establish the diagnosis. These diagnostic procedures may ultimately be applicable to newly discovered genes that directly influence the TGF-β signaling cascade and result in widespread and/or aggressive vascular disease. This narrative review will describe the classification of LDS, genetic etiologies, cardinal clinical manifestations, and best-evidence management recommendations for the panoply of serious sequelae associated with this syndrome.

Methods

This is a narrative review of the literature on LDS and related TGF-β signaling pathway syndromes, based on a systematic literature review, expert opinion, and standard-of-care practices from the center with the largest patient population of these disorders in the world. Experts from the various fields who manage the various phenotypic manifestations of this syndrome were included in the literature review and description of best practices.

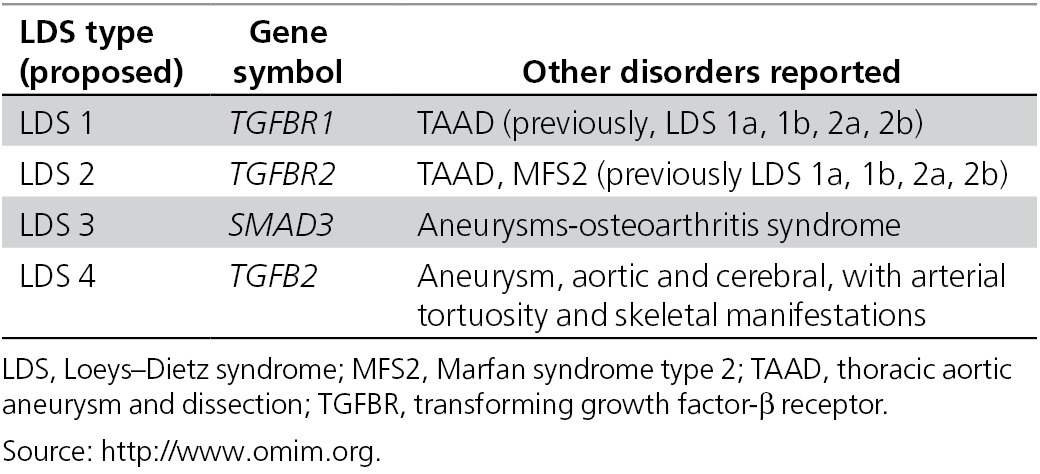

Classification and Genetics of LDS

In initial reports, LDS patients, defined as those with mutations in TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, were stratified into two types, depending on severity of craniofacial features (type 1) or cutaneous features (type 2).1 Given that vascular disease is the major concern for this patient group, and that patients with mutations in TGFBR1, TGFBR2, SMAD3, or TGFB2 show more widespread and/or aggressive vascular disease when compared with Marfan syndrome or thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection, irrespective of the severity of systemic features, we propose a revised nosology and that a mutation in any of these genes in combination with documented aneurysm or dissection should be sufficient for the diagnosis of LDS (Table 1). This will alert clinicians caring for these patients to the need for specialized patient counseling and management and highlight the evidence-based expansion of the clinical spectrum of LDS to include patients with minimal or no dysmorphic features. Such reasoning and practices have proven productive in the diagnosis and care of patients with Marfan and vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndromes.

Table 1

Chromosome deletions encompassing the TGFB2 gene (and hypothetically the SMAD3 gene) causing haploinsufficiency are sufficient to cause features of LDS. The size of the microdeletion may impact clinical presentation of these individuals, especially the presence of developmental delay. Mutations in all four of these genes have been associated with thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection category of disease, though this probably represents the mildest end of the Loeys–Dietz spectrum.3,4,5,6,8,9

Despite significant clinical variability within and between individuals with all four LDS gene defects, medical surveillance and treatments are similar. These medical guidelines reflect the current literature and expert knowledge both generalized and specific to all four types of LDS, even though most of the literature so far has focused on LDS 1 and LDS 2.

Clinical Manifestations and Management Recommendations, by Organ System

Cardiovascular

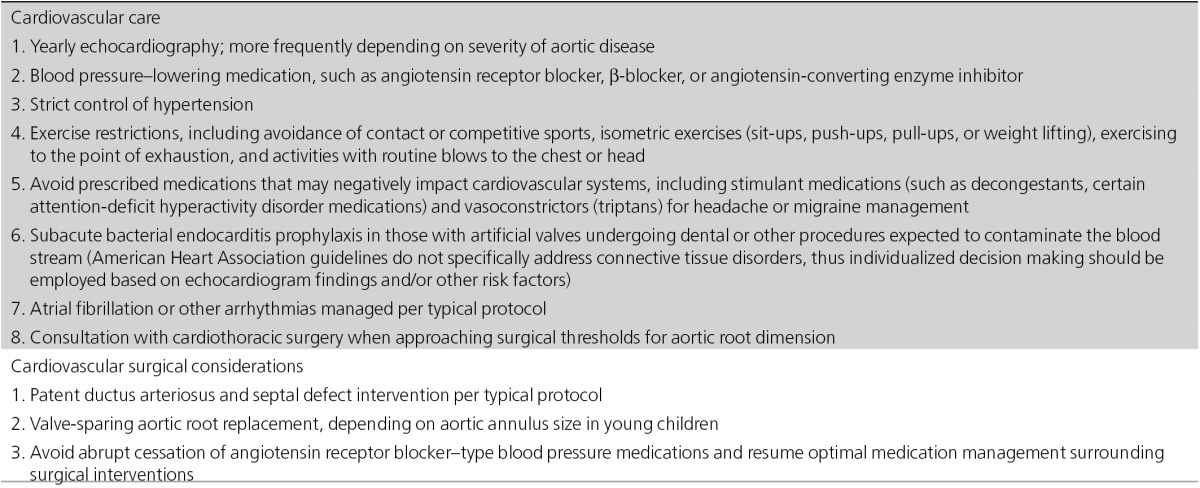

Rapidly progressive aortic aneurysmal disease is a distinct feature of LDS, requiring close monitoring. Individuals with LDS 1/2 with severe craniofacial features are at particularly high risk, known to have ruptures at early ages and at smaller dimensions than those with other aneurysm syndromes.1,2 Aortic dissection has been reported in individuals as young as 3 months and cerebral hemorrhage as young as 3 years.10,11 Initial reports of LDS 1/2 cohorts described a mean age of death at 26.1 years, with aortic dissection and cerebral hemorrhages as major causes of death.1 Better detection, surveillance, and early treatment are expected to extend the life span of affected individuals. Several reports show successful vascular interventions with low rates of intraoperative mortality as compared with other connective tissue disorders with pronounced vascular friability.1,12

All individuals with LDS require echocardiography at frequent intervals to monitor the status of the aortic root, ascending aorta, and heart valves. Minimally, this should occur yearly but may require more frequent imaging13 (Table 2).

Table 2

Congenital heart disease such as bicuspid aortic valve, atrial septal defect, or a patent ductus arteriosus are more frequently seen in LDS 1/2 than in the general population.14,15 Mitral valve prolapse and/or insufficiency can be seen in all types of LDS, with mild-to-severe mitral valve disease being reported.3,15,16 Some individuals require surgical intervention for aortic valve or mitral valve leakage, independent of aortic root status. These cardiac features should be managed per typical protocols.17

Atrial fibrillation (24%) and left ventricular hypertrophy have been reported in LDS 3 and may be seen in other LDS types at unknown frequency. Reported left ventricular hypertrophy was typically mild to moderate, mainly concentric, and occurred in the absence of aortic stenosis or hypertension.15,18 Impaired left ventricular systolic function has been reported in LDS 1.19 Arrhythmias and heart failure should be managed by typical protocols.

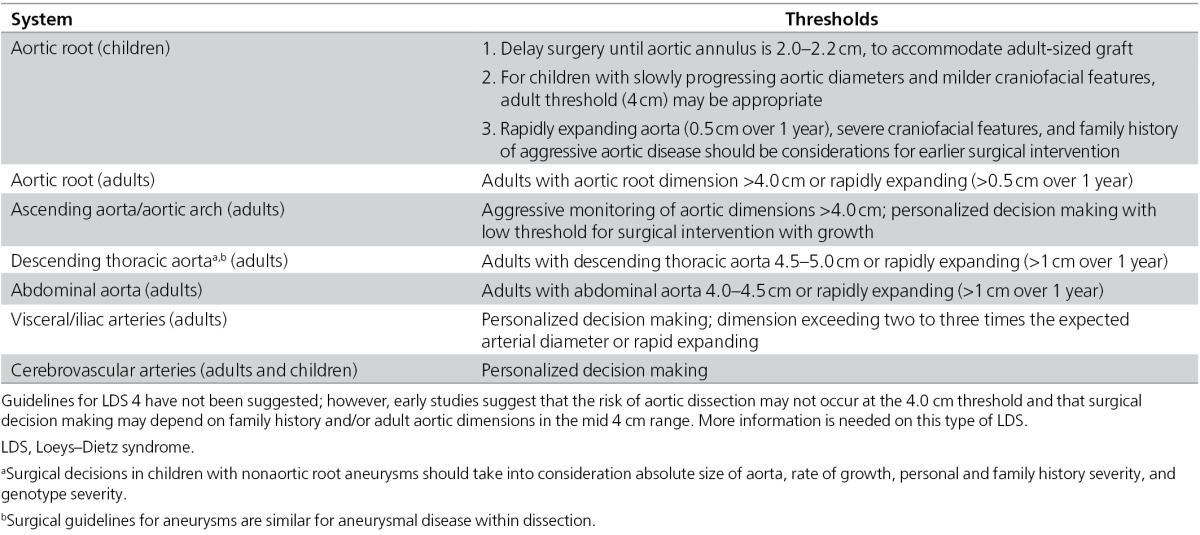

The decision to undergo aortic surgery is typically based on the absolute dimension of the aorta, rate of progression, valve function, severity of noncardiac features, family history, and information about genotype1,13 (Table 3). Unlike the increased risk of aortic dissection at or above the 5.0-cm aortic root dimension in Marfan syndrome, dissections have occurred in individuals with LDS 1, 2, or 3 at aortic dimensions of 3.9–4.0 cm1,3 and has been reported in LDS 4 at a dimension <5.0

cm1,3 and has been reported in LDS 4 at a dimension <5.0 cm.16

cm.16

Table 3

In view of the aggressive nature of the vascular disease and the low rate of complications associated with valve-sparing aortic root replacement surgery at experienced centers, surgery is being recommended at or around these dimensions. For adults with LDS 1 or 2, this includes surgical repair of the aortic root once the maximal dimension of the aortic root reaches 4.0 cm. Valve-sparing surgery is recommended to avoid the need for anticoagulation.

cm. Valve-sparing surgery is recommended to avoid the need for anticoagulation.

Successful valve-sparing aortic root replacement in young children (<1 year of age) has been performed.20 Initial management of LDS children, especially those with severe craniofacial features, considered surgical repair of the aorta once the measurement exceeded the 99th percentile for age and body surface area and the aortic valve annulus reached 1.8 cm.1 Consideration of the aortic valve annulus will allow for placement of a Dacron graft of sufficient size to accommodate somatic growth into adulthood. Aggressive medication regimens, with β-blockers and angiotensin receptor antagonists, may change the natural history of the disease and the thresholds for surgical repair. For example, at Johns Hopkins, among patients who are on aggressive medical therapy, regardless of craniofacial severity, we are attempting to delay surgery until the aortic annulus grows to 2.0–2.2

cm.1 Consideration of the aortic valve annulus will allow for placement of a Dacron graft of sufficient size to accommodate somatic growth into adulthood. Aggressive medication regimens, with β-blockers and angiotensin receptor antagonists, may change the natural history of the disease and the thresholds for surgical repair. For example, at Johns Hopkins, among patients who are on aggressive medical therapy, regardless of craniofacial severity, we are attempting to delay surgery until the aortic annulus grows to 2.0–2.2 cm. In the absence of a rapidly growing aorta, allowing the aortic root dimension to approach the 4.0

cm. In the absence of a rapidly growing aorta, allowing the aortic root dimension to approach the 4.0 cm threshold is a consideration.

cm threshold is a consideration.

Valve-sparing surgery may be contraindicated in the presence of leaflet fenestrations and asymmetry, acute aortic dissection in unstable patients, significantly enlarged root with leaflet irregularities, or bicuspid aortic valves with extensive calcification or dysfunction.21 A rapid increase in aortic root dimension (>0.5 cm/year) should prompt early surgical consultation.

cm/year) should prompt early surgical consultation.

Aneurysmal disease may present distally to the graft and in the aortic arch over time, and it is probably unrelated to the original procedure and due to underlying progression of LDS vascular disease. This raises the question of possible interventions including complete resection versus more conventional resection of the underneath side of the arch at the time of aortic root replacement. In children with severe disease who may have diminished ventricular function, this type of prolonged procedure should be avoided or considered with caution because of the requirement of prolonged cross-clamp time.22 Additionally, in children, it remains unclear whether additional aortic surgery is needed to accommodate adult-based vascular needs across the arch.23 Individual surgical situations suggest different preferences for hemiarch replacement versus elephant trunk versus staged replacement with no clear guidelines.24 Referral to a high-volume center is highly recommended for patients requiring extensive arch surgery.

Postoperative echocardiography at 3- to 6-month intervals is recommended for 1 year after surgery, and 6 months to 1 year thereafter.20 Coronary button aneurysms have been reported after valve-sparing aortic root replacement and are probably surgery related and not an LDS-specific complication. There has been one report of secondary surgery for revision of coronary buttons for aneurysmal dilation.25

Besides imaging surveillance and prophylactic surgical repair, other vascular management includes the use of blood pressure–lowering medication, avoidance of medications that act as stimulants or vasoconstrictors, and exercise restrictions. β-Blockade to reduce hemodynamic stress on the vasculature has been the standard-of-care treatment for individuals with syndromic aneurysm conditions.26 Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors have also been used at some institutions.27,28 Angiotensin receptor blockers may be particularly beneficial due to their effects on the TGF-β signaling cascade.29 If an angiotensin receptor blocker is used, it should be used to optimal titration (losartan: 2.0 mg/kg/day for children; 100

mg/kg/day for children; 100 mg/day for adults) (H. Dietz, personal communication). Ultrahigh dosing of newer-generation angiotensin receptor blockers may be considered in patients with severely progressive vascular disease even on optimal losartan dosage (H. Dietz, personal communication). Prophylactic medication use should be considered for individuals with LDS without aortic enlargement if they present with a family history of LDS with aortic enlargement or if the same mutation has been previously seen with vascular disease.

mg/day for adults) (H. Dietz, personal communication). Ultrahigh dosing of newer-generation angiotensin receptor blockers may be considered in patients with severely progressive vascular disease even on optimal losartan dosage (H. Dietz, personal communication). Prophylactic medication use should be considered for individuals with LDS without aortic enlargement if they present with a family history of LDS with aortic enlargement or if the same mutation has been previously seen with vascular disease.

Exercise restrictions to reduce stress on the aortic and arterial tissue include avoidance of contact or competitive sports, isometric exercises (sit-ups, push-ups, pull-ups, or weight lifting), and exercising to the point of exhaustion.

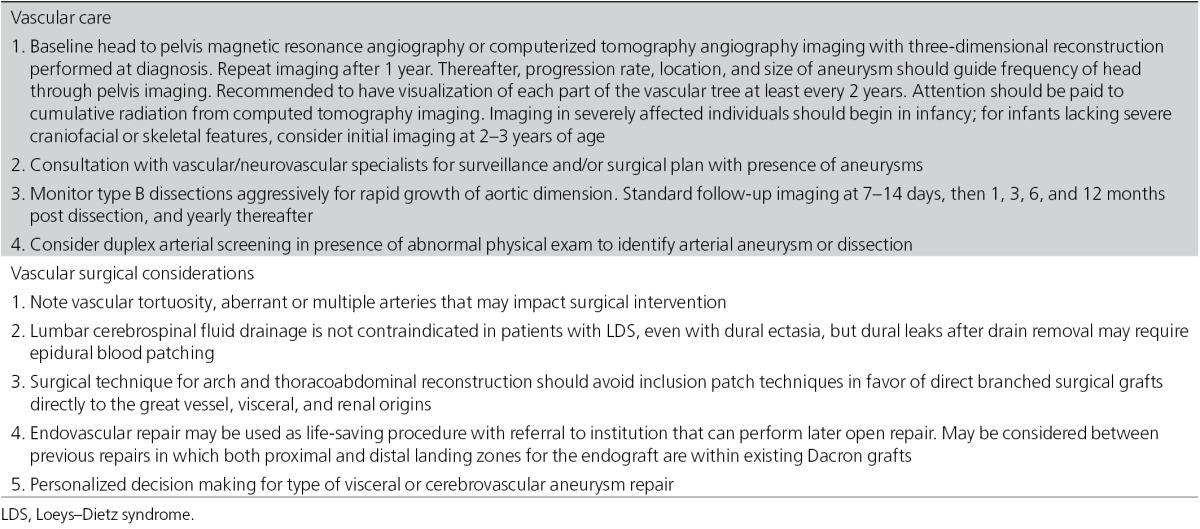

Diagnostic or baseline vascular imaging through magnetic resonance angiography or computerized tomography angiography with three-dimensional reconstruction of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be performed to assess for aneurysms throughout the aorta and arterial tree and arterial tortuosity (Table 4). Aneurysmal disease (including dissection) is not limited to the aortic root and has been reported in all other portions of the aorta and arterial branches of the head, neck, and thoracic and abdominal aorta.1,3,4 Nondilated coronary artery dissection has been reported in LDS 2 and 3.18,30 Routine imaging should be performed intermittently. Full vascular imaging should be performed on initial evaluation and at about a 2-year interval if there are no identified aneurysms or dissections (H. Dietz and B. Loeys, personal communication).

Table 4

Both magnetic resonance angiography and computerized tomography angiography technology are useful surveillance tools, but the trade-offs to consider include the risks of exposure to ionizing radiation, anesthesia, and different challenges to interpreting tortuous arteries or irregular anatomy versus aneurysm. Regardless of imaging technique utilized, the goal is obtaining serial measurements of all portions of the aorta and arteries.31 If there is known aneurysmal disease, vascular and/or neurovascular specialists should be consulted to determine a proper surveillance routine including frequency and type of imaging.

Arterial tortuosity can be generalized but is most typically observed in the neck vessels and has been reported in all types of LDS.1,3,14 Tortuous arteries are not associated with higher predisposition to aneurysm or dissection in these vessels. The presence of tortuous arteries may complicate the interpretation of artery measurement. It has been reported that increased vertebral arterial tortuosity measured by magnetic resonance angiography is a marker of adverse aortic outcome.32

Patients may need multiple surgical interventions for the aorta and/or arteries.33 Cameron et al.11 reported that 33% of the originally reported surgical cohort of LDS 1 and 2 required multiple vascular surgical interventions. Additionally, pseudoaneurysms post surgery may be underappreciated in this patient population.34

Type B aortic dissections have been reported at minimally dilated or nondilated aortic dimensions (3.7–4.2 cm) in LDS 1, 2, and 3 and at undocumented dimensions in LDS 4.3,5,35,36 Reports also document rapid expansion of aneurysm within dissections within a few days. This evidence suggests that individuals should be aggressively monitored postaortic dissection in the short (days) and long (months and years) term for progressive aneurysm growth within the dissection. Typical postdissection imaging should occur at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months and yearly thereafter.

cm) in LDS 1, 2, and 3 and at undocumented dimensions in LDS 4.3,5,35,36 Reports also document rapid expansion of aneurysm within dissections within a few days. This evidence suggests that individuals should be aggressively monitored postaortic dissection in the short (days) and long (months and years) term for progressive aneurysm growth within the dissection. Typical postdissection imaging should occur at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months and yearly thereafter.

Concerns have been raised about using thoracic stent grafts in patients with genetic aortic aneurysm syndromes, including LDS. Open repair of descending and thoracoabdominal aneurysms is preferred because endovascular repair may result in late failure due to continued dilation of fixation zone or persistent perfusion of the false lumen.37,38 However, thoracic endovascular repair has been successfully performed for aortic replacement where both proximal and distal landing zones for the endograft fixation were within existing Dacron grafts from previous vascular surgeries (i.e., intercostal patch aneurysms), suggesting a potential use for the aortic endograft procedure in selected LDS patient populations.39

There is a place for stent-graft repair as a life-saving “bridge” technique post dissection until the patient can be transferred to an institution where open repair is available. Stent-graft therapy may be justified in descending thoracic aortic rupture or to alleviate malperfusion syndromes (such as recalcitrant hypertension after renal artery malperfusion secondary to acute dissection). With the likelihood of repeat surgeries, preference should be given to uncovered stents or bare metal stents because some stent types may cause complications in future surgeries, for example, deformation during cross-clamping.40

In addition, retrograde dissection from descending thoracic aortic stent-graft therapy of acute type B dissection can occur, requiring emergency arch repair, associated with a 30–60% operative mortality. Retrograde dissection in patients with LDS has not yet been described in the literature. However, a study from China examining stent-graft repair of acute type B dissection demonstrated that retrograde dissection was the main complication of stent grafting in individuals with Marfan syndrome.41 Due to similarities in underlying pathophysiology, a similar concern for thoracic endovascular repair and retrograde dissection in LDS is justified. Similarly, oversizing of thoracic aortic stents for usage as a “bridge” from life-threatening complications of thoracic aortic disease in LDS should be minimal to no greater than 10%.

Aneurysms in the abdomen and lower extremities have also been reported. Bilateral common iliac artery aneurysm repairs have been performed through both open and stent-graft repairs.42,43 Bilateral popliteal aneurysms have been surgically repaired through open repair and endovascular repair.44 Abdominal branch artery aneurysm repairs have been successfully reported in LDS including coil embolization or open repair of splenic and hepatic arteries.22 Other than magnetic resonance angiography or computerized tomography angiography imaging, duplex arterial screening should be pursued with abnormal physical evaluation. Surgical intervention for visceral or iliac arteries should be pursued in rapidly expanding arteries or when arterial size exceeds two to three times the expected arterial diameter.

Optimal neurovascular surgical strategies have not been developed. It is uncertain whether there needs to be a lower threshold for treating intracranial aneurysms in individuals with LDS as opposed to those in the general population.45 In general, aneurysms that are large, growing, or causing symptoms are more likely to rupture. Endovascular strategies in this area have been successfully performed on saccular aneurysms.46 Stent-associated coil embolization and aneurysm clipping have been reported in various head and neck arteries in LDS.33,46,47,48 When deciding on the type of neurosurgical intervention, the age of the patient; the size, location, and shape of the aneurysm; the neurological and other medical status of the individual; potential need for repeated procedures; and complication of potential lifelong antiplatelet therapy should be considered.47 The diagnosis of LDS should not be a contraindication for intervention if otherwise indicated.

A clear understanding of the unique anatomy in individuals with LDS is crucial prior to surgical or endovascular intervention. Tortuosity of arteries and distal aneurysms, especially in access arteries, may impact surgery plan and choice of endovascular devices. Additionally, although the presence of dural ectasia does not contraindicate lumbar cerebrospinal fluid drainage for spinal cord protection during thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair, a dural leak after drain removal may require epidural blood patching (J. Black, personal communication). General strategies for vascular or endovascular surgery in LDS should include:

Experienced anesthesia team with ultrasound-guided access for central lines given cervicovertebral arterial tortuosity.

Strict hemodynamic control during surgical clamping or intra-arterial catheter manipulation to reduce iatrogenic dissection.

Frequent postoperative monitoring in intensive care unit or intermediate care unit.

Multiple surgical case reports suggest the complexity of aneurysmal disease in LDS and the need for personalized surgical strategies. Physicians should compare the benefits and limitations of open, endovascular, and hybrid repair, keeping in mind vascular tortuosity (especially of the aortic arch and thoracoabdominal aorta that may affect security of endovascular devices), past repairs, aberrant or multiple arteries (e.g., renal), current aneurysms, and natural history of progressive aneurysm development.

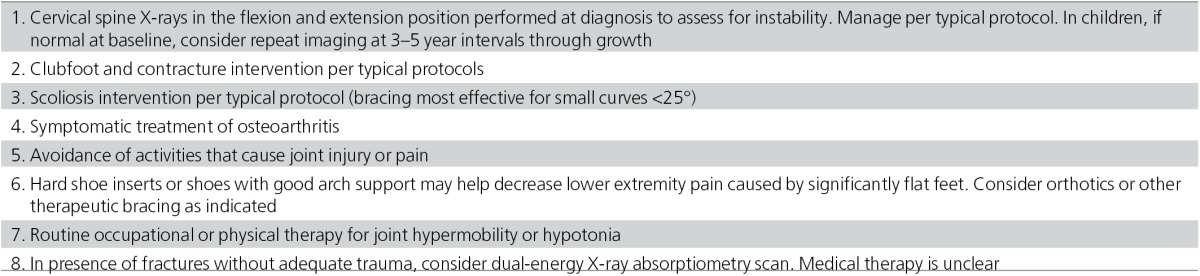

Orthopedics

Skeletal features in all types of LDS can show overlap with Marfan syndrome, including pectus deformity, scoliosis, and flat feet. Height and proportions are typically within the normal range, though evidence of skeletal overgrowth may be represented as arachnodactyly and pectus deformities.1,49 Camptodactyly and talipes equinovarus have been observed, as well as contractures of other joints. Extremity contractures in conjunction with joint hyperextension are unusual in the general population but common in LDS. Recommended management for orthopedics is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5

Many patients with talipes equinovarus respond well to stretching if the deformity is mild. Ponseti casting should be considered in moderate-to-severe cases (P. Sponseller, personal communication). Surgery is typically not recommended because it often results in overcorrection (hindfoot valgus).50 Joint hypermobility is also common, including congenital hip dislocation and recurrent or multiple joint subluxations.49 Hypotonia may be present in infancy, and patients may need early intervention therapies.27 Therapy and/or exercises that tone muscles and avoid hyperextension and excessive pounding on joints are recommended.

Cervical spine findings are prominent features in LDS 1/2 (51%), but presence in LDS 3 and 4 is unknown. Patients should be assessed for cervical spine abnormalities, subluxations, or instability, using flexion–extension X-rays of the cervical spine.1,50,51 Further computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated in some individuals. The frequency of repeat imaging has not been specifically identified for children. One recommendation is to perform imaging every 3–5 years during growth and after any surgery on the adjacent region of the spine (P. Sponseller, personal communication). Arthrodesis has been performed successfully for a variety of cervical spine malformations.

Scoliotic and kyphotic curve patterns have been reported and should be treated per typical protocols. Bracing may be indicated in mild curves (<25°) in growing children. Spondylolisthesis may be more likely to progress in patients with LDS than in the general population and should be monitored at least once per year until skeletal maturity. Patients with LDS typically tolerate spinal surgeries, though delayed bone healing has been reported (likely due to lack of fixation of pedicle screws).50 Careful attention should be paid to dural ectasia and the risk for dural tears. If concerns arise, Trendelenburg positioning should be used. Nutritional optimization should occur before any surgical intervention. All orthopedic concerns should be followed by an orthopedic surgeon and treated per typical protocols.

Pes planus is typically associated with inward rotation of the ankles and can contribute to leg fatigue, muscle cramps, or difficulty with ambulation. Some individuals respond well to hard-soled inserts for support. Surgery is typically not indicated unless significant pain, calluses, or bunions are occurring. Orthotics may also be a consideration for these indications.

Osteoarthritis is a significant feature in LDS 3, and first reports of individuals with SMAD3 gene mutations were described as aneurysms-osteoarthritis syndrome.3,15 Osteoarthritis has been observed in distal extremities, knees, hips, and spine. Disk degeneration, meniscal lesions, and osteochondritis dissecans have been reported at early age of onset (earliest age, 12 years).3,15 Many people with LDS come to attention due to aneurysmal disease and may not have specific imaging to assess osteoarthritis, thus this feature may be present in other types of LDS but not well defined. However, reports of LDS 4 have not described prominent degenerative joint disease.6 Symptomatic treatment is indicated.

The skeletal phenotype related to low bone mineral density and skeletal fragility (fractures) in young individuals has been reported in patients with LDS 2.52,53 Iliac bone histomorphometry confirmed low bone mass, and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan confirmed decreased lumbar spine area bone density. Patients with LDS have a higher incidence of fractures. A study by Sponseller and colleagues54 of individuals with LDS 1/2 revealed a 50% risk of fracture by 14 years of age. Limited dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry data supported the findings, revealing that at least 60% of patients had low or very low bone mineral density in the spine, hip, and/or femoral neck. Individuals should be counseled about low bone mineral density and higher risk of fractures. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans should be considered in the presence of fractures without significant trauma. However, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans in children present a challenge because they are often difficult to interpret and may require serial imaging to track changes. Osteopenia or osteoporosis may become increasingly important in this aging population. Currently, the effectiveness and outcome of bisphosphonate therapy in this population is unknown.

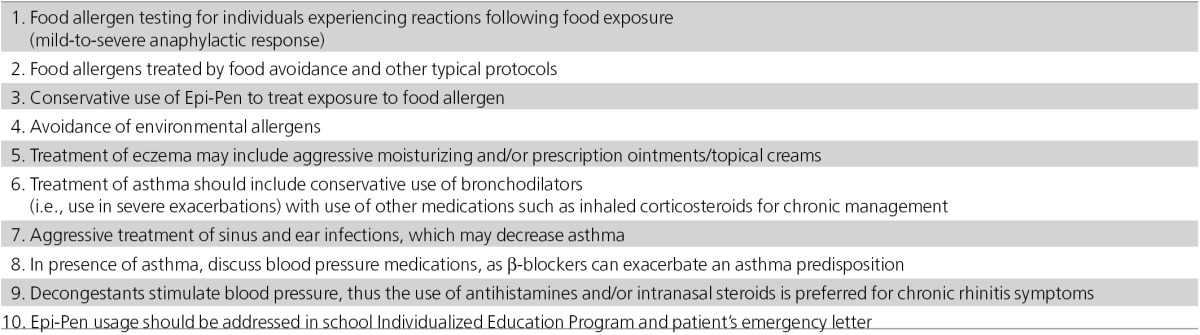

Allergy

LDS has been associated with a high prevalence of immunologic features including asthma, food allergy, eczema, and allergic rhinitis.55 A conservative prevalence estimate of food allergies in this population is 31% (compared with 6–8% prevalence in the general population), with most common food allergies mimicking those of the general population, including those to eggs, milk, soy, peanuts, and tree nuts. Symptoms range from acute, life-threatening reactions to more chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Antihistamines should be used to treat cutaneous or milder reactions, and Epi-Pens should be retained only for life-threatening reactions because they rapidly constrict blood vessels and could be harmful for individuals with underlying vascular disease.

An increased prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema is also evident in LDS, consistent with an overall increased risk of allergic disease in this syndrome. Sinus disease and ear infections may indicate mucous buildup secondary to allergen exposure, as well as altered craniofacial anatomy. Infections should be treated aggressively (Table 6).

Table 6

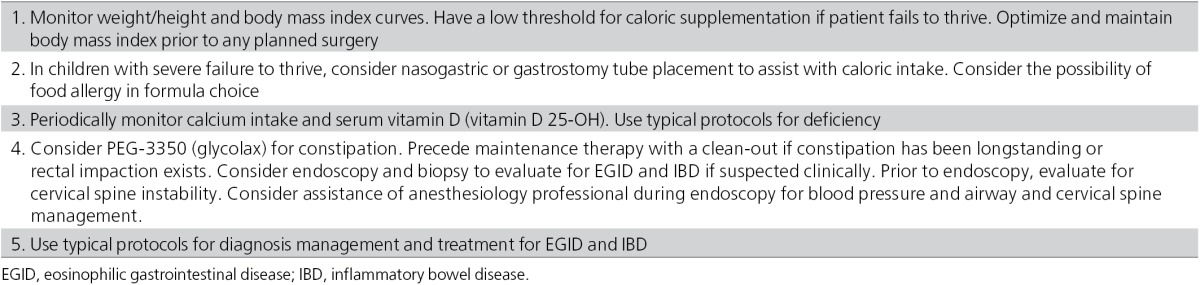

Gastroenterology and nutrition

Infants and children with LDS frequently present with failure to thrive.55 The cause is likely multifactorial and may include the impact of repeated surgical interventions and hospitalizations, increased baseline caloric expenditures in patients with incompletely treated asthma and eczema, and unrecognized food allergies and/or intestinal inflammation that both increase expenditures and decrease nutrient absorption. Management for gastroenterology and nutrition in patients with LDS generally follow traditional protocol (Table 7).

Table 7

There should be a low threshold for caloric supplementation in individuals meeting criteria for failure to thrive, especially if surgeries are planned. Patients should have height, weight, and body mass index plotted at each clinic visit. Given the prevalence of food allergy in LDS,55 strong consideration should be given to extensively hydrolyzed and amino acid formulas. If oral intake proves inadequate, nasogastric feedings, as well as placement of gastrostomy tubes (both surgically and percutaneously), have been used successfully in LDS (A. Guerrerio, personal communication).

Given the skeletal fragility and low bone mass seen in LDS,53 efforts should be made to ensure adequate calcium and vitamin D intake so that overall bone strength is not diminished further. Calcium intake should be calculated at each visit and supplemented if it is found to be below the levels published in the age/sex-specific guidelines.56 Serum levels of vitamin D should be monitored periodically and supplemented per published guidelines.57

Constipation is seen frequently in LDS patients, similar to other connective tissue disorders,58 and daily oral PEG-3350 (glycolax) is our treatment of choice. If constipation has been longstanding, a bowel clean-out (either oral or via nasogastric) may be necessary prior to beginning daily glycolax.59

LDS has been associated with a high prevalence of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease (EGID).55 In a recent case series, 66% of patients reported gastrointestinal complaints (including poor growth, repetitive vomiting, chronic abdominal pain, and dysphagia) that were potentially consistent with EGID. Of those having gastrointestinal biopsies, 6 of 10 had evidence of eosinophilic esophagitis, eosinophilic gastritis, and/or eosinophilic colitis. The majority of the patients with EGID showed improvement in clinical features with food avoidance diets.55

The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn disease is also increased in LDS, and there should be a low threshold for investigation in the presence of clinical symptoms (A. Guerrerio, personal communication). There is no evidence that work-up or treatment for EGID or inflammatory bowel disease is different in this population than in the general population. As of this writing, typical protocols are recommended for investigating and managing EGID and inflammatory bowel disease.

Given the increased prevalence of EGID and inflammatory bowel disease, endoscopy is sometimes required. Prior to endoscopy, the presence of cervical spine instability should be determined, although its existence is not an absolute contraindication to endoscopy. Consideration should be made for performing the procedure with the assistance of an anesthesiologist or certified registered nurse anesthetist, and good blood pressure control should be maintained. Given the connective tissue aspects of LDS, there does exist, at least theoretically, an increased risk of perforation, although this has not been seen to date (A. Guerrerio, personal communication).

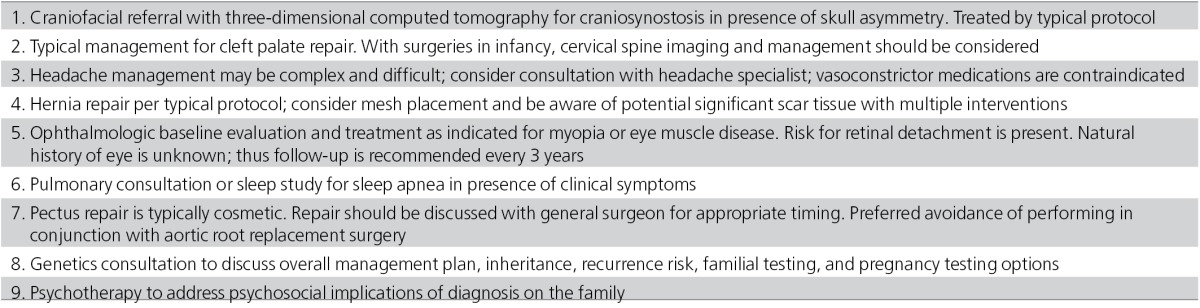

Other management

A variety of other complications and birth defects that can range from mild to severe may require identification and management (Table 8).

Table 8

Craniofacial. Cleft palate and craniosynostosis are reported in LDS 1/2. Treatment is per typical protocol, taking into consideration cervical spine status on anesthesia management during early surgical interventions. A three-dimensional head computed tomography can assess for craniosynostosis. Most commonly, the sagittal suture is prematurely closed, but the coronal, metopic, and squamosal sutures can also be involved.14 Facial asymmetry may represent a milder malformation of craniofacial development. Consultation with a craniofacial program may be useful in determining utility and necessity of diagnostic computed tomography imaging.

Due to the craniofacial differences, high and narrow palates may cause dental malocclusion that will need orthodontic intervention. Anecdotally, many individuals present with decreased dental enamel, causing significant damage of primary teeth requiring extraction (H. Dietz and B. Loeys, personal communication). Early and routine dental evaluations are necessary.

Uvula anomalies (mildest form of cleft palate) can range from a bifid uvula, uvula with raphe, to broad or long uvula. Although considered part of the original triad of features, many individuals may not have this feature.

Cutaneous. Cutaneous findings in LDS include velvety, thin, translucent skin with easy bruising and visible veins.1 Scars may be atrophic and wound healing may be delayed.13 In some individuals lacking craniofacial features, these cutaneous features may be a prominent distinguishing feature of LDS from Marfan syndrome or thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. Striae and/or facial milia may also be present.60

General surgery. Splenic or bowel rupture is a rare but life-threatening manifestation reported in individuals with LDS 1/2.1 Prolapse of the bowel, uterus, and bladder has also been reported.3,15,18

Inguinal, umbilical, hiatal hernias have been observed and may occur postsurgically or recurrently. Mesh repair should be considered.

Varicose veins have been reported in LDS, and at least in LDS 3, there is the suggestion that they may be surgically resistant.15

The Nuss procedure for pectus deformity repair is typically considered cosmetic, as they rarely impact heart or lung function. If pursued, it is recommended to not be performed concurrently with aortic root surgery, as this can prolong recovery with added pain and/or other lung complications.

Neurology. Learning disability is a rare primary manifestation in individuals with LDS 1/2, and if present, it is likely related to craniosynostosis or hydrocephalus.1 It has not been reported as a feature in LDS 3. Those individuals presenting with a chromosome microdeletion causing LDS 4 may have intellectual disability depending on the extent of the chromosome deletion.5

Neuroradiological findings of Chiari malformation have been rarely reported in LDS. Hydrocephalus may exist unrelated to Chiari malformation.1 Dural ectasia seems to appear in an increasing frequency as more radiological imaging of individuals is being performed.3,6,61

Any aneurysms and dissections in the carotid and vertebrobasilar systems may require treatment to prevent further complications such as strokes. The presence of these finding should prompt evaluation by neuroradiology or neurointerventional specialists. Chronic aspirin use may be indicated in these individuals.

Headaches appear to be a feature of LDS that may significantly impact day-to-day living in individuals with LDS, occurring in as much as 50% of patient reports.15 They do not seem to co-occur with cerebrovascular abnormalities. Keeping a food/environment diary may help identify headache triggers, and sleep studies or ophthalmological evaluations may help identify other medical causes to headaches. The impact of dural ectasia in headache development has been described in Marfan syndrome, but there is no clear and effective treatment for this finding,62 although for an acute dural tear or chronic cerebral spinal fluid leakage, blood patch placement is indicated. β-Blockers may provide relief for some individuals. Vasoconstrictor class of medications is contraindicated in this patient population. Comorbidities of fatigue and joint pain also impact quality of life.63

Ophthalmology. A major distinguishing feature from Marfan syndrome is the lack of lens dislocation in LDS. Although not clinically significant, blue or dusky sclera can be a diagnostic clue. Retinal detachment and cataracts have been reported in LDS 1/2.15 Myopia is less frequent and severe than in Marfan syndrome. A variety of eye muscle problems including strabismus, amblyopia, and exotropia are seen in LDS and respond to typical protocols of patching and/or surgery.14,15 Retinal tortuosity has been described, but clinical significance is unknown.2

Pulmonary. Pneumothoraces and restrictive lung disease are reported pulmonary manifestations. Additionally, obstructive sleep apnea may be present, even in young children, and sleep studies should be considered in the presence of clinical symptoms such as sleep apnea, snoring, morning headaches, and daytime tiredness. Pulmonary artery dilation encroaching upon the right mainstem bronchus has been reported in a 3-month-old infant with LDS 2, presenting as respiratory distress.64

Cancer. Somatic mutations (mutations in specific tissues) in TGFBR2 have been reported in cancer cells, but risk of cancer in individuals with LDS is unknown.65 TGF-β signaling is recognized to have a role in cancer including suppression of carcinogenesis in the initial stages of cancer and promotion of tumor progression and metastasis in the later stages.66 Milewicz and colleagues9 reported the presence of basal and squamous cell carcinoma and breast, pancreatic, parotid gland, and renal cell carcinoma in individuals with LDS 1/2. Acute myeloid leukemia has been reported in an individual with LDS 1/2.67 At present, no specific cancer pattern has emerged, and it is unknown whether cancer risk is increased in individuals with LDS. Normal cancer-screening guidelines are recommended.

Psychosocial adjustment. A genetic diagnosis, especially one with significant health burden and somewhat uncertain prognosis, can generate a multitude of emotional reactions in patients and their caretakers. A diagnosis can affect relationships with and between parents, spouses, siblings, children, extended family, and nonfamily support systems. Adequate attention should be paid to coping and communication styles within the family, with referral to therapists or counselors as necessary. Those receiving the diagnosis will need assistance understanding the importance of medication compliance and physical activity restrictions. There may be significant emotional burden related to medical appointments and surgical interventions, the natural history of the disease in the extended family, feelings of isolation or unfairness, and/or fear of the future, both for the affected individual and other family members. Depression and anxiety over medical concerns may exist on a short-term or chronic basis, and appropriate treatments and coping strategies should be discussed.

Genetics. Consultation with a genetics professional is recommended at diagnosis to review the multisystem manifestations of LDS, to help develop an imaging surveillance plan and to coordinate interdisciplinary care. Additionally, a genetics professional can assist in reviewing the family history to determine whether echocardiogram screening or familial genetic testing is warranted, especially in the families of LDS patients with mild external features.

Genetics professionals can provide educational and support resources, including necessary documentation about the diagnosis, letters for school or work, and LDS family contacts to aid in support. Letters for school should include information about the diagnosis, physical education restrictions, allergy management, impact of skeletal and joint features, and psychological impact of the disorder. This information can help the child, family, and school to develop an individualized education program. Emergency letters should address risk for catastrophic events including aortic, arterial, or hollow organ rupture, retinal detachment, and management for allergen exposure. (Supplementary Appendixes A, B, and C online).

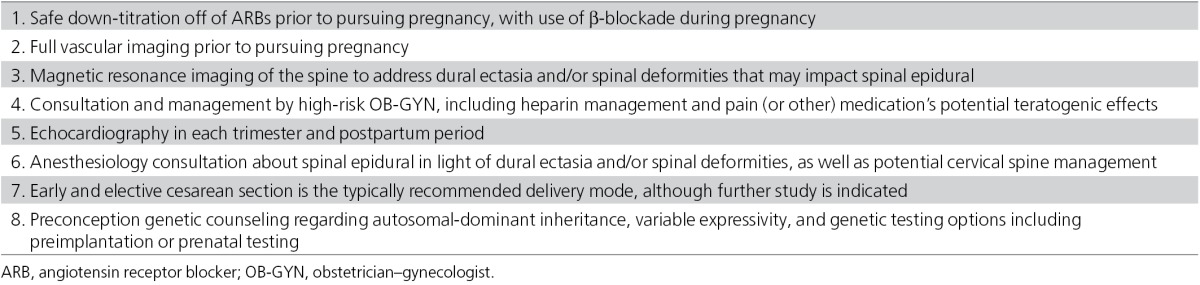

Pregnancy. Women with LDS can tolerate and have successful pregnancies and deliveries, although pregnancies should be considered high risk. In the absence of predictive characteristics of women who may have complications, counseling women about specific risks remains a challenge. In 21 pregnancies among 12 women with LDS 1/2, 6 women had a major complication either during pregnancy or immediately postpartum, comprised of 4 aortic dissections and 2 uterine ruptures.1 These occurred in first, second, and third pregnancies. Two additional women experienced severe uterine hemorrhage independent of pregnancy. Arterial rupture may also be a pregnancy or postpartum complication. In an additional report of 9 women with LDS 1 with 32 children and 22 women with LDS 2 with 61 children, only 1 woman experienced a vascular complication associated with the pregnancy, passing away of aortic dissection 3 weeks postpartum.9 Of 13 women having a total of 23 pregnancies with LDS 3, 1 had severe postpartum hemorrhage, but no other vascular complications or uterine ruptures were reported.15,18 Although few cases of LDS 4 have been reported, a “mother died in childbirth” in one individual with LDS 4.16 Large-scale studies are necessary (Table 9).

Table 9

In Marfan syndrome, a high risk of complication including death from aortic dissection exists in pregnancies of women with aortic dimension >4.5 cm.68 There is an approximately 10% risk of dissection in pregnancy when the aortic dimension is above 4.0

cm.68 There is an approximately 10% risk of dissection in pregnancy when the aortic dimension is above 4.0 cm, and 1% risk in women with normal aorta size.69,70 Due to the more aggressive nature of LDS, pregnancy in this population could hold a higher risk of vascular catastrophe. Successful pregnancies in women with aortic dimensions of 3.9

cm, and 1% risk in women with normal aorta size.69,70 Due to the more aggressive nature of LDS, pregnancy in this population could hold a higher risk of vascular catastrophe. Successful pregnancies in women with aortic dimensions of 3.9 cm have been reported, although there are no follow-up data to predict impact of pregnancy on aneurysm progression or formation.71 Additionally, successful treatment of a type A dissection in a woman with LDS 1 at 16 weeks of gestation has been reported.72 Valve-sparing aortic root replacement prior to pursuing pregnancy, especially in women around the 4.0-cm surgical threshold, should be considered.

cm have been reported, although there are no follow-up data to predict impact of pregnancy on aneurysm progression or formation.71 Additionally, successful treatment of a type A dissection in a woman with LDS 1 at 16 weeks of gestation has been reported.72 Valve-sparing aortic root replacement prior to pursuing pregnancy, especially in women around the 4.0-cm surgical threshold, should be considered.

Patients should be referred to high-risk obstetric care and delivery in a tertiary-care center.13 Prior to pursuing a pregnancy, cervical spine instability should be excluded in the event that general anesthesia with emergency vascular surgery is required. Consultation with an anesthesiologist should be pursued to review spinal anatomy and possible dural ectasia for possible contraindications to spinal epidurals. Multidisciplinary input for women with known aneurysms or dissections is optimal to formulate a pregnancy and delivery plan.

Cardiovascular medications should be addressed, with safe down-titration and discontinuation of angiotensin receptor blockers prior to pursuing a pregnancy. β-Blocker usage is recommended throughout pregnancy. Other pain, anticoagulation, and/or other medical therapy should be thoroughly discussed prior to pregnancy to reduce teratogenic effects on the fetus.

Early delivery and the avoidance of high intra-abdominal pressure by means of cesarean section may reduce the risk of obstetric complications. No specific recommendations can be made, however, due to the absence of studies comparing the efficacy of cesarean and vaginal deliveries. Poor wound healing with cesarean section or episiotomies may occur.13

Preconception genetic counseling is indicated to address recurrence risk and diagnostic testing options. The recurrence risk when one parent is affected is 50%. When a couple has a child with an apparently de novo gene mutation, counseling should include approximately ≤1% risk of second child with LDS attributed to germline mosaicism.1 Prenatal diagnosis through amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling and preimplantation genetic diagnosis are available options for all types of LDS. Ultrasound may be a screening tool for clubfoot or camptodactyly and fetal echocardiograms may detect in utero aortic dilation, but these are not diagnostic.73

As more individuals are diagnosed with LDS, our knowledge about the range of medical features and best management principles will continue to evolve. This review of the literature and expert advice for current management recommendations is formulated with the goal of improving quality and longevity of life for those affected with LDS.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Loeys–Dietz Syndrome Foundation for its financial sponsorship of these management tools and Stephen Zeiler for reviewing the neurovascular review. G.M. received a grant from the Loeys–Dietz Syndrome Foundation supporting this work.

References

- Loeys BL, Schwarze U, Holm T, et al. Aneurysm syndromes caused by mutations in the TGF-beta receptor. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:788–798. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Loeys BL, Chen J, Neptune ER, et al. A syndrome of altered cardiovascular, craniofacial, neurocognitive and skeletal development caused by mutations in TGFBR1 or TGFBR2. Nat Genet. 2005;37:275–281. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- van de Laar IM, Oldenburg RA, Pals G, et al. Mutations in SMAD3 cause a syndromic form of aortic aneurysms and dissections with early-onset osteoarthritis. Nat Genet. 2011;43:121–126. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Regalado ES, Guo DC, Villamizar C, NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project et al. Exome sequencing identifies SMAD3 mutations as a cause of familial thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection with intracranial and other arterial aneurysms. Circ Res. 2011;109:680–686. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay ME, Schepers D, Bolar NA, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in TGFB2 cause a syndromic presentation of thoracic aortic aneurysm. Nat Genet. 2012;44:922–927. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau C, Guo DC, Hanna N, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Go Exome Sequencing Project et al. TGFB2 mutations cause familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections associated with mild systemic features of Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44:916–921. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Van Laer L, Proost D, Loeys BL. Educational paper: connective tissue disorders with vascular involvement: from gene to therapy. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:997–1005. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pannu H, Fadulu VT, Chang J, et al. Mutations in transforming growth factor-beta receptor type II cause familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Circulation. 2005;112:513–520. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tran-Fadulu V, Pannu H, Kim DH, et al. Analysis of multigenerational families with thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections due to TGFBR1 or TGFBR2 mutations. J Med Genet. 2009;46:607–613. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A, Westesson PL. Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:1015. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JA, Loeys BL, Nwakanma LU, et al. Early surgical experience with Loeys-Dietz: a new syndrome of aggressive thoracic aortic aneurysm disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:S757–S763; discussion S785–90. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linde D, Bekkers JA, Mattace-Raso FU, et al. Progression rate and early surgical experience in the new aggressive aneurysms-osteoarthritis syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:563–569. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan-Kirchner M, Epplen JT, Faivre L, et al. Clinical utility gene card for: Loeys-Dietz syndrome (TGFBR1/2) and related phenotypes. 10.1038/ejhg.2011.68; published online 27 April 2011; Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hemelrijk C, Renard M, Loeys B. The Loeys-Dietz syndrome: an update for the clinician. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25:546–551. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- van de Laar IM, van der Linde D, Oei EH, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of the SMAD3-related aneurysms-osteoarthritis syndrome. J Med Genet. 2012;49:47–57. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Renard M, Callewaert B, Malfait F, et al. Thoracic aortic-aneurysm and dissection in association with significant mitral valve disease caused by mutations in TGFB2. Int J Cardiol. 2013;165:584–587. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu Y, Kosho T, Magota M, et al. Progressive aortic root and pulmonary artery aneurysms in a neonate with Loeys-Dietz syndrome type 1B. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:417–421. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linde D, van de Laar IM, Bertoli-Avella AM, et al. Aggressive cardiovascular phenotype of aneurysms-osteoarthritis syndrome caused by pathogenic SMAD3 variants. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:397–403. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Eckman PM, Hsich E, Rodriguez ER, Gonzalez-Stawinski GV, Moran R, Taylor DO. Impaired systolic function in Loeys-Dietz syndrome: a novel cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:707–708. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Cleuziou J, Eichinger WB, Schreiber C, Lange R. Aortic root replacement with re-implantation technique in an infant with Loeys-Dietz syndrome and a bicuspid aortic valve. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31:117–119. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Patel ND, Arnaoutakis GJ, George TJ, et al. Valve-sparing aortic root replacement in Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:556–560; discussion 560–1. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ozker E, Vuran C, Saritas B, Türköz R. Valve-sparing replacement of the ascending aorta and aortic arch in a child with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:1184–1185. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas WI. Total arch replacement procedure in a child with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:1186. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Augoustides JG, Plappert T, Bavaria JE. Aortic decision-making in the Loeys-Dietz syndrome: aortic root aneurysm and a normal-caliber ascending aorta and aortic arch. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:502–503. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tweddell JS, Earing MG, Bartz PJ, Dunham-Ingles JL, Woods RK, Mitchell ME. Valve-sparing aortic root reconstruction in children, teenagers, and young adults. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:587–590; discussion 590–1. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Shores J, Berger KR, Murphy EA, Pyeritz RE. Progression of aortic dilatation and the benefit of long-term beta-adrenergic blockade in Marfan's syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1335–1341. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yetman AT, Beroukhim RS, Ivy DD, Manchester D. Importance of the clinical recognition of Loeys-Dietz syndrome in the neonatal period. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1199–e1202. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt MD, Pinto N, Hawkins JA, Mitchell MB, Kouretas PC, Yetman AT. Cardiovascular surgery in children with Marfan syndrome or Loeys-Dietz syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:1327–1332; discussion 1332–3. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Matt P, Habashi J, Carrel T, Cameron DE, Van Eyk JE, Dietz HC. Recent advances in understanding Marfan syndrome: should we now treat surgical patients with losartan. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:389–394. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Fattori R, Sangiorgio P, Mariucci E, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a young woman with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:1216–1218. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde I, Simpson J, Beerbaum P. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Cardiol Young. 2010;20:210–213. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SA, Orbach DB, Geva T, Singh MN, Gauvreau K, Lacro RV. Increased vertebral artery tortuosity index is associated with adverse outcomes in children and young adults with connective tissue disorders. Circulation. 2011;124:388–396. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- LeMaire SA, Pannu H, Tran-Fadulu V, Carter SA, Coselli JS, Milewicz DM. Severe aortic and arterial aneurysms associated with a TGFBR2 mutation. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4:167–171. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Marine L, Gupta R, Gornik HL, Kashyap VS. Glue embolus complicating the endovascular treatment of a patient with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:1350–1353. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Suh YJ, Kwon HW, Kim GB, et al. A case of near total aortic replacement in an adolescent with loeys-dietz syndrome. Korean Circ J. 2012;42:288–291. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RS, Fazel S, Schwarze U, et al. Rapid aneurysmal degeneration of a Stanford type B aortic dissection in a patient with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:242–243, 243.e1. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman JJ, Ramponi F, Bannon PG, Jeremy R. Familial aortic aneurysm and dissection due to transforming growth factor-beta receptor 2 mutation. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12:863–865. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ML, Wechsler SB, Hughes GC. Two-stage total aortic replacement for Loeys-Dietz syndrome. J Card Surg. 2010;25:223–224. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JB, McCann RL, Hughes GC. Total aortic replacement in Loeys-Dietz syndrome. J Card Surg. 2011;26:304–308. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Neri E, Tommasino G, Tucci E, Benvenuti A, Ricci C. A complex thoracoabdominal aneurysm in a Loeys-Dietz patient: an open, hybrid, anatomic repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:e88–e90. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dong ZH, Fu WG, Wang YQ, et al. Retrograde type A aortic dissection after endovascular stent graft placement for treatment of type B dissection. Circulation. 2009;119:735–741. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Casey K, Zayed M, Greenberg JI, Dalman RL, Lee JT. Endovascular repair of bilateral iliac artery aneurysms in a patient with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26:107.e5–107.e10. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Martens T, Van Herzeele I, De Ryck F, et al. Multiple aneurysms in a patient with aneurysms-osteoarthritis syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:332–335. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson MA, Vlachakis I, Valenti D. Bilateral popliteal artery aneurysms in a young man with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:486–488. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Joshua B, Bederson JB, Awad IA, et al. AHA scientific statement, recommendations for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000;102:2300–2308. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt MR, Morton RP, Mai JC, Ghodke B, Hallam DK. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms in Loeys-Dietz syndrome. J Neurointerv Surg. 2012;4:e37. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes BD, Powers CJ, Zomorodi AR. Clipping of a cerebral aneurysm in a patient with Loeys-Dietz syndrome: case report. Neurosurgery. 2011;69:E746–E755; discussion E55. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ohman JW, Charlton-Ouw KM, Azizzadeh A. Endovascular repair of an internal mammary artery aneurysm in a patient with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:837–840. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Loeys BL, Dietz HC. Loeys-Dietz syndrome Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP.ed). GeneReviews™ [Internet] University of Washington; Seattle, WA; 1993 . http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1133/ ( accessed January 7th, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Erkula G, Sponseller PD, Paulsen LC, Oswald GL, Loeys BL, Dietz HC. Musculoskeletal findings of Loeys-Dietz syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1876–1883. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa SB, Lambot-Juhan K, Rio M, et al. Expanding the skeletal phenotype of Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1178–1183. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Amor IM, Edouard T, Glorieux FH, et al. Low bone mass and high material bone density in two patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome caused by transforming growth factor beta receptor 2 mutations. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:713–718. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmani S, Tebben PJ, Lteif AN, et al. Germline TGF-beta receptor mutations and skeletal fragility: a report on two patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:1016–1019. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tan EW, Offoha RU, Oswald GL, et al. Increased fracture risk and low bone mineral density in patients with loeys-dietz syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:1910–1914. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Guerrerio AL, Oswald G, et al. TGFβ receptor mutations impose a strong predisposition for human allergic disease. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:195ra94. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. National Academy Press; Washington, DC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Adib N, Davies K, Grahame R, Woo P, Murray KJ. Joint hypermobility syndrome in childhood. A not so benign multisystem disorder. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:744–750. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SS, Liptak GS, Colletti RB, et al. Constipation in infants and children: evaluation and treatment. A medical position statement of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;29:612–626. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd BM, Braverman AC, Anadkat MJ. Multiple facial milia in patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:223–226. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues VJ, Elsayed S, Loeys BL, Dietz HC, Yousem DM. Neuroradiologic manifestations of Loeys-Dietz syndrome type 1. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1614–1619. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Foran JR, Pyeritz RE, Dietz HC, Sponseller PD. Characterization of the symptoms associated with dural ectasia in the Marfan patient. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;134A:58–65. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Law C, Bunyan D, Castle B, et al. Clinical features in a family with an R460H mutation in transforming growth factor beta receptor 2 gene. J Med Genet. 2006;43:908–916. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppler KM, Kirse DJ, Thompson JT, Haldeman-Englert CR. Loeys-Dietz syndrome presenting as respiratory distress due to pulmonary artery dilation. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:1212–1215. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Grady WM, Myeroff LL, Swinler SE, et al. Mutational inactivation of transforming growth factor beta receptor type II in microsatellite stable colon cancers. Cancer Res. 1999;59:320–324. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Akhurst RJ, Derynck R. TGF-beta signaling in cancer–a double-edged sword. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:S44–S51. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Togashi Y, Sakoda H, Sugahara H, Asagoe K, Matsuzawa Y. [Loeys-Dietz syndrome with acute myeloid leukemia] Rinsho Ketsueki. 2008;49:664–667. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Harris IS. Management of pregnancy in patients with congenital heart disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;53:305–311. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb KJ, Smith JC, Clarke B, Donnai P, Harris R. Outcome of pregnancy in women with Marfan's syndrome. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:201–206. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter JP, Repke JT, Morales AJ, Murphy EA, Pyeritz RE. A prospective longitudinal evaluation of pregnancy in the Marfan syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1599–1606. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman G, Baris HN, Hirsch R, et al. Loeys-Dietz syndrome in pregnancy: a case description and report of a novel mutation. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2009;26:35–37. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kunishige H, Ishibashi Y, Kawasaki M, Yamakawa T, Morimoto K, Inoue N. Surgical treatment for acute type A aortic dissection during pregnancy (16 weeks) with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;60:764–767. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Viassolo V, Lituania M, Marasini M, et al. Fetal aortic root dilation: a prenatal feature of the Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2006;26:1081–1083. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Article citations

TGF-β signaling in the cranial neural crest affects late-stage mandibular bone resorption and length.

Front Physiol, 15:1435594, 15 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39473613 | PMCID: PMC11519526

Thoracoabdominal aortic replacement in a 6-year-old boy with Loeys-Dietz syndrome.

J Cardiothorac Surg, 19(1):530, 18 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39289723 | PMCID: PMC11409485

Clinical Approach to Genetic Cerebral Arteriopathy in the Adult Patient With Ischemic Stroke.

Neurol Genet, 10(5):e200182, 21 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39176127 | PMCID: PMC11341007

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Acute Transverse Myelitis in a Patient With Type 2 Loeys-Dietz Syndrome: A Report of a Rare Case From India.

Cureus, 16(7):e65524, 27 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39188477 | PMCID: PMC11346573

Explainable artificial intelligence in deep learning-based detection of aortic elongation on chest X-ray images.

Eur Heart J Digit Health, 5(5):524-534, 25 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39318689 | PMCID: PMC11417491

Go to all (220) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Ectopia lentis in Loeys-Dietz syndrome type 4.

Am J Med Genet A, 182(8):1957-1959, 28 May 2020

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 32462795

Massive hemoptysis in Loeys-Dietz syndrome.

Am J Med Genet A, 170(3):725-727, 27 Nov 2015

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 26614122

Loeys-Dietz syndrome and pregnancy: The first ten years.

Int J Cardiol, 226:21-25, 11 Oct 2016

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 27780078

Review

Genetic testing of 10 patients with features of Loeys-Dietz syndrome.

Clin Chim Acta, 456:144-148, 11 Feb 2016

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 26877057