Abstract

Background

Although fatigue, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety are associated with pain in breast cancer patients, it is unknown whether acupuncture can decrease these comorbid symptoms in cancer patients with pain. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of electroacupuncture (EA) on fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress in breast cancer survivors who experience joint pain related to aromatase inhibitors (AIs).Methods

The authors performed a randomized controlled trial of an 8-week course of EA compared with a waitlist control (WLC) group and a sham acupuncture (SA) group in postmenopausal women with breast cancer who self-reported joint pain attributable to AIs. Fatigue, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression were measured using the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The effects of EA and SA versus WLC on these outcomes were evaluated using mixed-effects models.Results

Of the 67 randomly assigned patients, baseline pain interference was associated with fatigue (Pearson correlation coefficient [r]=0.75; P < .001), sleep disturbance (r=0.38; P=.0026), and depression (r=0.58; P < .001). Compared with the WLC condition, EA produced significant improvements in fatigue (P=.0095), anxiety (P=.044), and depression (P=.015) and a nonsignificant improvement in sleep disturbance (P=.058) during the 12-week intervention and follow-up period. In contrast, SA did not produce significant reductions in fatigue or anxiety symptoms but did produce a significant improvement in depression compared with the WLC condition (P=.0088).Conclusions

Compared with usual care, EA produced significant improvements in fatigue, anxiety, and depression; whereas SA improved only depression in women experiencing AI-related arthralgia.Free full text

Electro-acupuncture for fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress in breast cancer patients with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia: A randomized trial

Abstract

Purpose

Although fatigue, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety are associated with pain in breast cancer patients, it is unknown if acupuncture can decrease these co-morbid symptoms in cancer patients with pain. This study aimed at evaluating the effect of electro-acupuncture on fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress in breast cancer survivors who experience joint pain related to aromatase inhibitors (AIs).

Patients and methods

We performed a randomized controlled trial of an eight-week course of electro-acupuncture (EA) as compared to waitlist control (WLC) and sham acupuncture (SA) in postmenopausal women with breast cancer who self-reported joint pain attributable to aromatase inhibitors. Fatigue, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression were measured by the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The effects of EA and SA vs. WLC on these outcomes were evaluated using mixed-effects models.

Results

Of the 67 randomly assigned patients, baseline pain interference was associated with fatigue (Pearson correlation coefficient r =0.75, p<0.001), sleep disturbance (r=0.38, p=0.0026), and depression (r= 0.58, p<0.001). Compared to the WLC, EA produced significant improvement in fatigue (p=0.0095), anxiety (p=0.044), and depression (p=0.015) and non-significant improvement in sleep disturbance (p=0.058) during the 12 week intervention and follow up period. In contrast, SA did not produce significant reduction in fatigue and anxiety symptoms, but produced significant improvement in depression compared with WLC (p=0.0088).

Conclusion

Compared to usual care, EA produced significant improvement in fatigue, anxiety, and depression, whereas SA improved only depression in women experiencing AI-related arthralgia.

Clinical Trial Registration

NCT01013337

INTRODUCTION

Arthralgia, or joint pain, is a common and bothersome side effect of aromatase inhibitors (AIs)1 experienced by nearly 50% of post-menopausal breast cancer patients who receive AI therapies.2 Among all of the side effects associated with AIs, arthralgia is the most discussed symptom in online breast cancer-specific message boards, which indicates the intrusive nature of this symptom on patients’ daily living.3 Further, the experience of arthralgia results in premature discontinuation of AIs,4 which may negatively impact disease free and overall breast cancer survival.5

Emerging evidence suggests that acupuncture, a therapy originated from Traditional Chinese Medicine, may be effective in the management of AI-related arthralgia.6–8 Acupuncture appears to be safe with few minor and self-limiting side effects (e.g. needling pain, local bruising) noticed in the trials. While the definitive efficacy of acupuncture for arthralgia related to AI use requires rigorously conducted trials of larger sample sizes, longer follow up, and refinement of active and placebo interventions, the initial effect sizes observed in these trials indicate potentially clinically meaningful reduction in pain.6, 8

Although it is unknown in the setting of AI-therapy, research has demonstrated that pain in breast cancer patients is often associated with fatigue, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression.9–12 Biologically, the clustering of these symptoms with pain may be explained by hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) dys-regulation.11 In addition, the dynamic relationship between innate immune inflammatory response and neuro-endocrine pathways may account for both the development and persistence of these symptoms.13 Together, pain and co-morbid non-pain symptoms have a synergistic negative effect on quality of life in breast cancer patients.10 In animal models, acupuncture impacts both the HPA axis14 and SNS system,15 providing a biologically plausible explanation for acupuncture’s effect on not only AI-related arthralgia but also on fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress in these women. We analyzed pre-specified secondary non-pain symptom outcomes in a recently completed Phase-II randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the short term effects and safety of electro-acupuncture (EA) for AI-related arthralgia compared to a sham acupuncture placebo (SA) and usual care waitlist control (WLC).8 We chose EA because of its clear physiological effect on the endogenous opioid system (e.g. enkaphalin and beta-endorphin) and pain reduction demonstrated in animal models.16 For this paper, we evaluated the specific effects of EA and sham acupuncture (SA) as compared to usual care WLC on fatigue, sleep, anxiety, and depression.

METHODS

We have previously published the primary outcome of our clinical trial which demonstrated the preliminary efficacy of EA on AI related pain.8 We summarize the methods here for convenience.

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

In brief, we conducted a three arm RCT (EA, SA, and WLC) from September 2009 through May 2012 at the Abramson Cancer Center of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, a tertiary care academic medical center in Philadelphia. Eligible patients were women with a history of early stage breast cancer (stages I-III) who were currently receiving an aromatase inhibitor (Anastrozole, Letrozole, or Exemestane), had joint pain for at least three months that they attributed to their AI, reported a worst pain rating of at least four or greater on an 11 point (0–10) numerical rating scale in the preceding week, reported at least 15 days with pain in the preceding 30 days, and provided informed consent. We excluded individuals who had metastatic (stage IV) breast cancer or who had a history of a bleeding disorder. The institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania approved the study protocol.

STUDY DESIGN

We randomly assigned participants to treatment groups using computer-generated numbers sealed in opaque envelopes. We used permutated block sizes of three or six to ensure a two to one randomization of acupuncture to WLC allocation. Subsequently for the acupuncture group, the treating acupuncturist opened a second envelope using computer-generated numbers at the first acupuncture visit to determine if the subject was to receive EA or SA. We educated all participants on joint pain, staying physically active, and continuing with current medical treatments (including prescription and over-the-counter pain medications) as usual. Patients in the WLC were allowed to receive 10 real acupuncture treatments after Week 12 follow-up. As previously reported, blinding was evaluated by credibility rating at Week 8. Participants considered both EA and SA to be credible (4.3 vs. 4.0, p=0.54).8

INTERVENTIONS

Two licensed non-physician acupuncturists with 8 and 20 years of experience, respectively, administered interventions twice a week for two weeks, then weekly for six more weeks, for a total of ten treatments over eight weeks. The detailed protocol has been previously published.8 In brief, for the EA group, the acupuncturist chose at least four local points around the joint with the most pain. Additionally, at least four distant points were used to address non-pain symptoms such as depression/anxiety and fatigue that are commonly seen in conjunction with pain. The needles (30 mm or 40mm and 0.25 gauge, (Seirin-America Inc., Weymouth, MA) were inserted until “De Qi” (sensation of soreness, tingling, etc.) was reported by the patient.17 Two pairs of electrodes were connected at the needles adjacent to the painful joint(s) with two hertz electro-stimulation provided by a TENS unit. The needles were left in place for 30 minutes with brief manipulation at the beginning and the end of therapy. Sham acupuncture was performed using Streitberger non-penetrating needles at non-acupuncture, non-trigger points at least 5 cm from the joint where pain was perceived to be maximal. The acupuncturists avoided eliciting the “De Qi” sensations by only minimally manipulating the needles apart from their initial contact with the skin. Instead of adding a small electric current to the needles, the acupuncturists turned on the dial of the TENS unit to a different channel so that the subject could observe the light blinking without receiving the electricity. The frequency and duration of treatments between EA and SA groups were identical.

OUTCOME MEASURES AND FOLLOW-UP

Along with the a priori primary outcome, pain intensity and interference, measured by the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI),18 our a priori secondary outcomes, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) of fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress, were measured at Baseline, weeks 2, 4, and 8 during treatment, and at Week 12 (four weeks post-treatment). We measured fatigue by the summative score of the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI). This 9-item instrument was designed to assess one construct of fatigue severity in cancer and non-cancer populations 19 on a numerical rating scale ranging from 0–10, with 10 indicating the greatest severity or interference. The score of the scale was found to be reliable and valid in multiple languages and diverse cancer populations. We measured sleep with the global score of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The 19-item PSQI instrument produces a global sleep quality score and seven specific component scores: quality, latency, duration, disturbance, habitual sleep efficiency, use of sleeping medications, and daytime dysfunction. Global scores range from 0–21 with higher scores indicating poor sleep quality and high sleep disturbance.20 Psychological distress was measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), a 14-item scale with seven items measuring depression and seven items measuring anxiety.21 The scale uses varying response items. The score of the scale has been shown to be both reliable and valid in diverse groups of cancer patients.22

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We based the sample size estimation of this study on the primary outcome of pain. To detect an effect size of 1.6 at 80% power and significance level 0.05, we needed 18 subjects per arm.8 We used ANOVA or Pearson’s chi-squared test to compare baseline variables among groups. To evaluate whether the non-pain PROs are associated with pain intensity and interference, we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficient among these outcomes at baseline. Because our outcome measures were repeated over time, we assessed differences in changes from Baseline to Week 12 between EA and WLC and between SA and WLC using separate mixed-effect models.23 We treated time and group as categorical variables and included a random intercept term in the mixed-effect model with adjustment for baseline values. Tests of intention-to-treat differences between EA and WLC arms and between SA and WLC arms with respect to the change were based on time-intervention interactions in the mixed-effect models. We calculated P-values both for joint-tests across all time points and for individual tests at each time point. Goodness of fit of the mixed-effects models were checked using residual plots. We did not find evidence for violations of any model assumptions and lack of fit. The impact of missing data on the results was evaluated through sensitivity analyses including last observation carry forward and analyses of completers only. We did not find that any results differed from our intent to treat analyses. We calculated between-group differences with 95% confidence intervals at each time point. Two-sided P values are presented and interpreted at a statistical significance level of 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA (version 12.0, STATA Corporation, College Station, TX) and SAS (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

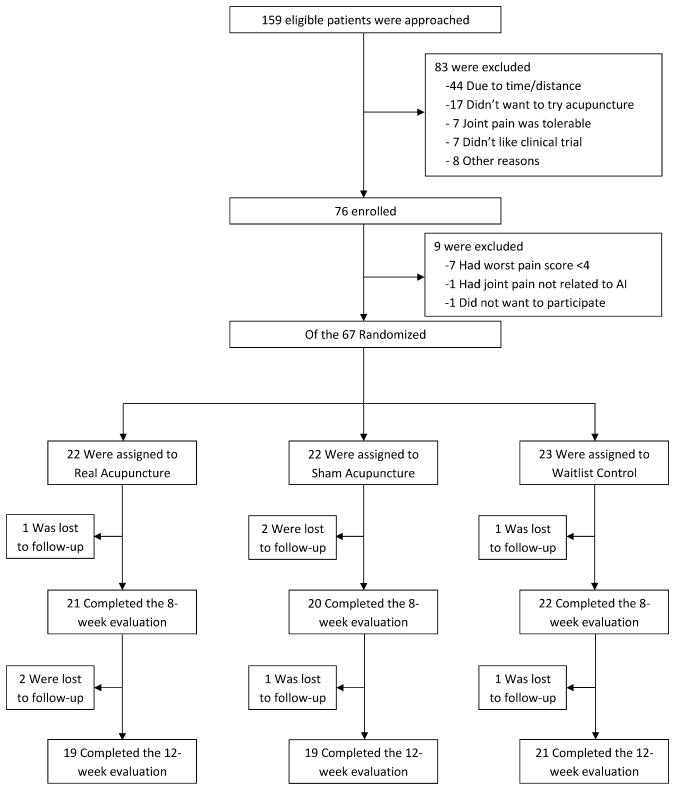

As previously reported,8 we screened 159 and enrolled 76 patients between September 2009 and May 2012 (See Figure 1 for consort diagram). Of the 76 patients who qualified for baseline evaluation, nine were further excluded (seven had patient-reported pain levels lower than the inclusion criteria, one had severe pain unrelated to AIs, and another did not want to participate), and the 67 eligible participants were randomly assigned to EA, SA, or WLC. Among participants, 21 (95.4%) in the EA group and 20 (90.5%) in the SA group received all ten treatments. Four (6%) and eight (12%) patients among all randomized were lost to follow-up before Week 8 and 12, respectively.8

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PATIENTS

Table 1 shows baseline data for the 67 participants. The mean age of the women enrolled was 59.7 years, (range 41 to 76), and 48 (71.6%) were White, while 16 (23.9%) were Black. Forty-four patients (66%) were receiving anastrozole at the time of randomization, and, on average, participants had been on an AI for 25.9 (range 3 to 56) months. The mean (standard deviation) BPI pain intensity score at Baseline was 4.9 (1.6) and the pain-related interference score was 3.7 (2.2). The BFI score was 3.7 (2.4), the PSQI score was 8.2 (3.8), the HADS-Anxiety score was 6.0 (3.8), and the HADS-Depression score was 4.0 (3.0). Baseline characteristics were well balanced and not significantly different among the three groups.

Table 1

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Participants1

| Variables | EA (N=22) | SA (N=22) | WLC (N=23) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.5±10.1 | 60.9±6.5 | 60.6±8.2 |

|

| |||

| Race - # of subjects (%)2 | |||

White White | 13 (59) | 17 (77) | 18 (78) |

Non-White Non-White | 9 (41) | 5 (23) | 5 (22) |

|

| |||

| Education - # of subjects (%) | |||

High school or less High school or less | 2 (9) | 3 (14) | 5 (22) |

College or above College or above | 20 (91) | 19 (86) | 18 (78) |

|

| |||

| Stage - # of subjects (%) | |||

Stage I Stage I | 11 (50) | 11 (50) | 11 (48) |

Stage II Stage II | 8 (36) | 7 (32) | 7 (30) |

Stage III Stage III | 3 (14) | 4 (18) | 5 (22) |

|

| |||

| Aromatase Inhibitors - # of subjects (%) | |||

Anastrozole (Arimidex) Anastrozole (Arimidex) | 13 (59) | 16 (73) | 15 (65) |

Letrozole (Femara) Letrozole (Femara) | 4 (18) | 4 (18) | 4 (17) |

Exemestane (Aromasin) Exemestane (Aromasin) | 5 (23) | 2 (9) | 4 (17) |

|

| |||

| Duration of AI (months) | 26.9±17.3 | 19.5±16.9 | 31.1±22.1 |

|

| |||

| Pain – BPI | |||

Intensity Intensity | 5.1±1.8 | 4.7±1.7 | 4.9±1.3 |

Interference Interference | 3.8±2.6 | 3.4±2.3 | 3.9±1.7 |

|

| |||

| Fatigue – BFI | 3.7±2.5 | 3.5±2.5 | 3.8±2.1 |

|

| |||

| Sleep Quality – PSQI | 8.7±4.4 | 7.6±4.1 | 8.3±2.4 |

|

| |||

| Psychological Distress - HADS | |||

Anxiety Anxiety | 6.2±3.6 | 4.8±3.4 | 6.9±4.2 |

Depression Depression | 4.1±3.0 | 3.4±2.3 | 4.3±3.6 |

Abbreviations: EA, Electroacupuncture; SA, Sham acupuncture; WLC, Waitlist control; BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

BASELINE CORRELATION BETWEEN PAIN AND NON-PAIN SYMPTOMS

At Baseline, we found significant correlations between pain and several non-pain symptoms. Fatigue (Pearson correlation coefficient r=0.54, p<0.001), sleep disturbances (r=0.28, p=0.025), and depression (r=0.35, p=0.0037) were associated with pain intensity. Fatigue (r=0.75, p<0.001), sleep disturbances (r=0.38, p=0.0026), and depression (r=0.58, p<0.001) were also associated with pain-related interference. Anxiety was not associated with either pain intensity (r=0.059, p=0.64) or pain interference (r=0.20, p=0.099).

CHANGE IN FATIGUE, SLEEP, AND PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS

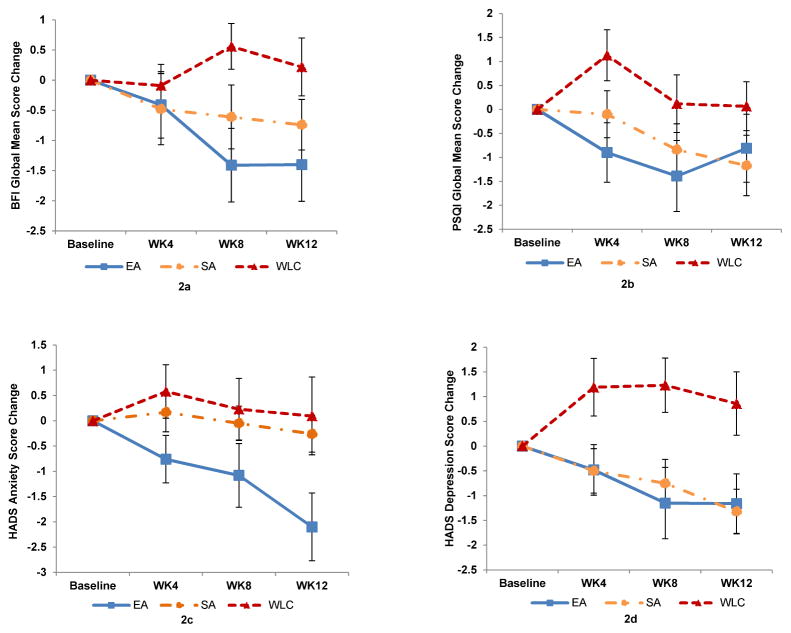

Table 2 and Figure 2 show changes in fatigue, sleep, anxiety, and depression at weeks 4, 8, and 12 compared to Baseline among three treatment groups.

Abbreviations: EA, Electroacupuncture; SA, Sham acupuncture; WLC, Waitlist control; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

Table 2

Changes in Symptom Outcomes Among all Subjects1

| Variables | Mean Change from Baseline (95% CI) | Between Group Difference (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA | SA | WLC | EA vs. WLC | P-Value2 | SA vs. WLC | P-Value2 | |

| BFI severity | 0.0095 | 0.18 | |||||

|

| |||||||

Week 4 Week 4 | −0.4 (−1.6 to 0.7) | −0.5 (−1.7 to 0.7) | −0.1 (−0.8 to 0.6) | −0.3 (−1.6 to 1.0) | 0.57 | −0.4 (−1.8 to 1.0) | 0.38 |

|

| |||||||

Week 8 Week 8 | −1.4 (−2.7 to −0.1) | −0.6 (−1.7 to 0.5) | 0.5 (−0.2 to 1.3) | −2.0 (−3.4 to −0.5) | 0.0034 | −1.2 (−2.5 to 0.1) | 0.046 |

|

| |||||||

Week 12 Week 12 | −1.4 (−2.7 to −0.1) | −0.7 (−1.6 to 0.1) | 0.2 (−0.8 to 1.2) | −1.6 (−3.2 to −0.07) | 0.022 | −0.9 (−2.2 to 0.3) | 0.091 |

|

| |||||||

| PSQI | 0.058 | 0.31 | |||||

|

| |||||||

Week 4 Week 4 | −0.9 (−2.2 to 0.4) | −0.1 (−1.1 to 0.9) | 1.1 (−0.01 to 2.3) | −2.0 (−3.8 to −0.3) | 0.0074 | −1.2 (−2.7 to 0.2) | 0.10 |

|

| |||||||

Week 8 Week 8 | −1.4 (−2.9 to 0.2) | −0.8 (−2.0 to 0.3) | 0.1 (−1.1 to 1.4) | −1.5 (−3.5 to 0.4) | 0.087 | −0.9 (−2.6 to 0.7) | 0.19 |

|

| |||||||

Week 12 Week 12 | −0.8 (−2.3 to 0.7) | −1.2 (−2.5 to 0.1) | 0.07 (−1.0 to 1.2) | −0.9 (−2.7 to 0.9) | 0.20 | −1.2 (−2.9 to 0.5) | 0.13 |

|

| |||||||

| HADS-Anxiety | 0.044 | 0.91 | |||||

|

| |||||||

Week 4 Week 4 | −0.8 (−1.7 to 0.2) | 0.2 (−0.6 to 1.0) | 0.6 (−0.5 to 1.7) | −1.3 (−2.8 to 0.09) | 0.062 | −0.4 (−1.8 to 0.9) | 0.50 |

|

| |||||||

Week 8 Week 8 | −1.1 (−2.4 to 0.2) | −0.05 (−0.8 to 0.7) | 0.2 (−1.0 to 1.5) | −1.3 (−3.1 to 0.5) | 0.075 | −0.3 (−1.7 to 1.2) | 0.67 |

|

| |||||||

Week 12 Week 12 | −2.1 (−3.5 to −0.7) | −0.3 (−1.0 to 0.5) | 0.09 (−1.5 to 1.7) | −2.2 (−4.3 to −0.1) | 0.006 | −0.3 (−2.1 to 1.4) | 0.59 |

|

| |||||||

| HADS-Depression | 0.015 | 0.0088 | |||||

|

| |||||||

Week 4 Week 4 | −0.5 (−1.5 to 0.6) | −0.5 (−1.4 to 0.4) | 1.2 (−0.03 to 2.4) | −1.7 (−3.2 to −0.1) | 0.039 | −1.7 (−3.2 to −0.2) | 0.022 |

|

| |||||||

Week 8 Week 8 | −1.2 (−2.6 to 0.4) | −0.8 (−1.7 to 0.2) | 1.2 (0.08 to 2.4) | −2.4 (−4.2 to −0.6) | 0.0031 | −2.0 (−3.5 to −0.5) | 0.0056 |

|

| |||||||

Week 12 Week 12 | −1.1 (−2.4 to 0.1) | −1.3 (−2.3 to −0.4) | 0.8 (−0.5 to 2.2) | −2.0 (−3.8 to −0.2) | 0.011 | −2.2 (−3.8 to −0.5) | 0.0024 |

PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

Abbreviations: EA, Electroacupuncture; SA, Sham acupuncture; WLC, Waitlist control; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory;

Fatigue

In the mixed-effects models, EA produced significant improvement in the BFI score as compared to WLC over time (p=0.0095) while SA did not produce improvement (p=0.18). Compared to WLC, patients in the EA group had a greater reduction in the BFI score (mean difference in reduction of −2.0 points, 95% confidence interval [CI], −3.4 to −0.5, p=0.0034, Cohen’s d=0.96) at Week 8, and the effect persisted at Week 12 (−1.6, 95% CI −3.2 to −0.07, p=0.022, Cohen’s d=0.86).

Sleep

In the mixed-effects models, compared to WLC, both EA and SA produced non-significant improvement of the PSQI score over time (p=0.058 and p=0.31, respectively). Compared to WLC, patients in the EA had non-significant improvement in the PSQI score (−1.5, 95% CI, −3.5 to 0.4, p=0.087, Cohen’s d= 0.63) at Week 8.

Anxiety

In the mixed-effects models, compared to WLC, EA produced significant improvement of the HADS-Anxiety score over time (p=0.044) while SA did not (p=0.91). Compared to WLC, patients in the EA group had non-significant improvement in the HADS-Anxiety score (−1.3 points, 95% CI, −3.1 to 0.5, p=0.075, Cohen’s d=0.53) at Week 8. The change in HADS-Anxiety scores was increased and significant between EA and WLC by Week 12 (−2.2, 95% CI, −4.3 to −0.1, p=0.006, Cohen’s d= 0.68).

Depression

In the mixed-effects models, both EA (p=0.015) and SA (p=0.0088) produced significant improvement of HADS-Depression scores compared to WLC over time. Compared to WLC, EA improved HADS-Depression scores by 2.4 points (95% CI, −4.2 to −0.6, p=0.0031, Cohen’s d=0.75) at Week 8. Similarly, SA improved HADS-Depression scores as compared to WLC by 2.0 points (95% CI, −3.5 to −0.5, p=0.0056, Cohen’s d=0.89) at Week 8. The effects of both EA and SA for depression were maintained at Week 12.

DISCUSSION

In this randomized controlled trial, we found that electro-acupuncture produced significant and clinically relevant improvement in fatigue, anxiety, and depression as compared to usual care among breast cancer patients who experienced arthralgia related to AI use. In contrast, sham acupuncture produced similar significant benefit for depression, but not for fatigue and anxiety. These findings have important implications for pain and symptom management and research in cancer patients.

Our study is consistent with a small but growing body of literature that suggests that acupuncture may be effective for pain,6 fatigue,24 anxiety, and depression.25 Instead of using fixed points, we individualized acupuncture treatment based on a protocol and allowed the acupuncturists not only to treat joint pain, but also to address symptoms such as fatigue and psychological distress.8 This tailored approach may account for the significant improvement produced by EA on these non-pain symptoms. Our comparison with usual care provided a clinical context for understanding the relevance of these effects. For example, the Cohen’s d for fatigue is 0.96, which suggests a large clinical effect; while the Cohen’s d of 0.68 for anxiety suggests a moderately large effect.26 The Cohen’s d for sleep was 0.63, indicating a moderately large effect, but this did not quite reach statistical significance. Each of these outcomes is highly correlated and supportive of the efficacy of EA. But given the small group size and the potential concern about multiple comparisons, these results should be interpreted as preliminary. Additional studies will be needed to confirm the efficacy of EA. Our study also included a 4-week no treatment follow up period, which suggests that the effect of acupuncture for these symptoms persisted, at least for the short term. This is clinically important as continued weekly treatments of acupuncture for a long period of time can be cost-prohibitive and time consuming for most breast cancer patients.

Our study also provides novel understanding of how fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress relate to pain in patients with clinically meaningful AI-related arthralgia. We found that pain-related interference is highly correlated with fatigue (r=0.75), and moderately correlated with depression (r=0.58) and sleep (r=0.35). These findings extend the prior research in breast patients undergoing chemotherapy 10 or in patients with metastatic/recurrent diseases.10 Our findings suggest that clusters of pain, fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress may exist in patients receiving AIs, requiring further evaluation of the shared bio-behavioral pathway of these symptoms as well as the impact of these symptoms on patients.

The neuroendocrine-immune mechanism of pain and behavioral symptoms (e.g. fatigue, sleep) has been proposed by prior researchers.13 Thorton et al. found that shared variance of plasma levels of cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone, epinephrine, and norepinephrine are associated with shared variance of the pain, depression, and fatigue symptom cluster in breast cancer patients with advanced diseases.11 These findings indicate that both HPA axis and SNS regulation are part of a common mechanistic pathway.11 More recently, cytokine genetic variations were found to be associated with fatigue and depressive symptoms, which provides further evidence for potential neuro-endocrine-immune mechanisms.27 Acupuncture has been found to influence the HPA axis14 and SNS,28 in addition to potentially exerting an immune-modulatory effect,15 which offers biological plausibility as to why it can simultaneously address common pain and non-pain symptoms in cancer patients. Future clinical trials incorporating appropriate experimental design and biomarkers may help uncover the mechanisms underlying the effect of acupuncture for these common symptoms.

Several limitations need to be acknowledged. While our original study was powered to detect a difference in pain between EA and WLC,8 it was not powered to detect a statistically significant difference between EA and SA. In this paper, we provide the effect size of both EA and SA as compared to the WLC in fatigue, sleep, anxiety, and depression, but the study is under-powered to detect differences between EA and SA. As such, we did not statistically compare effects between EA and SA but provided the magnitude of change in EA and SA so that future research can be powered. Additionally, we evaluated multiple outcomes raising concerns for multiple comparisons. Our results should be considered supportive of the efficacy of EA but that additional studies will be required to confirm these findings. Further, 12% of subjects were lost to follow up. We performed sensitivity analyses by analyzing completers only as well as carrying last values forward. These results were consistent with our intent-to-treat analyses. Finally, sham control may not function as a physiologically inert placebo due to tactile stimulation of sensory receptors.

Conclusions

Among breast cancer patients experiencing clinically important joint symptoms attributable to aromatase inhibitors, pain is significantly associated with fatigue, sleep, and depression. Electro-acupuncture shows promise as a therapy to address these symptoms in addition to pain. These preliminary findings need to be confirmed in a larger trial that includes longer follow-up. Careful incorporation of behavioral instrument and biomarkers in the trial setting can help elucidate the mechanisms underlying both the symptom cluster and the effect of acupuncture.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source:

NIH/NCCAM R21 AT004695; Dr. Mao is a recipient of the NCCAM K23 AT004112 award.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr. Farrar has consulted for Pfizer and AstraZeneca and Dr. DeMichele has research support from Pfizer unrelated to aromatase inhibitors. The other co-authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28917

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1002/cncr.28917

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1002/cncr.28917

Article citations

A randomized controlled study of auricular point acupressure to manage chemotherapy-induced neuropathy: Study protocol.

PLoS One, 19(9):e0311135, 26 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39325795 | PMCID: PMC11426428

Efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on sleep quality in patients with cancer-related insomnia: a network meta-analysis.

Front Neurol, 15:1421469, 20 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39372699 | PMCID: PMC11449704

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Acupuncture for Aromatase Inhibitor-Induced Arthralgia in Breast Cancer: An Umbrella Review.

Breast Care (Basel), 19(5):252-269, 08 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39439861

Review

Acupuncture for fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a study protocol for a pragmatic, mixed method, randomised controlled trial.

BMJ Open, 14(7):e077514, 30 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39079925 | PMCID: PMC11293412

Efficacy of acupuncture treatment for breast cancer-related insomnia: study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial.

Front Psychiatry, 15:1301338, 23 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38846918 | PMCID: PMC11153751

Go to all (78) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

A randomised trial of electro-acupuncture for arthralgia related to aromatase inhibitor use.

Eur J Cancer, 50(2):267-276, 24 Oct 2013

Cited by: 70 articles | PMID: 24210070 | PMCID: PMC3972040

Feasibility trial of electroacupuncture for aromatase inhibitor--related arthralgia in breast cancer survivors.

Integr Cancer Ther, 8(2):123-129, 01 Jun 2009

Cited by: 32 articles | PMID: 19679620 | PMCID: PMC3569528

[Aromatase inhibitors and arthralgia].

Magy Onkol, 55(1):32-39, 31 Mar 2011

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 21617789

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCCIH NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: K23 AT004112

Grant ID: R21 AT004695

NCI NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: L30 CA110987

NIMH NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: T32 MH065218

National Institutes of Health (1)

Grant ID: R21 AT004695