Abstract

Background

The global obesity epidemic has created new challenges, including venous thromboembolisms (VTE) in obese adolescents. The data on whether to reduce the dose of low-molecular heparin in obese adults is conflicting, and information on adolescent patients is scarce.Objectives

Our primary goal was to describe dosing, anti-Xa levels, and outcomes of overweight and obese adolescents who received reduced doses of enoxaparin at the initiation of therapy. The secondary goal was to compare their outcomes to overweight and obese adolescents who received standard 1 mg/kg dosing to determine if future trials for dose reduction are warranted.Patients/methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of overweight and obese patients between the ages of 12 and 18 years old diagnosed with VTE who were treated with reduced dosing (RD) of enoxaparin, comparing their dosing, anti-Xa levels, and outcomes to overweight and obese adolescents who received standard dosing (SD).Results

RD patients (n=19) achieved therapeutic mean initial anti-Xa levels that were similar to SD patients (n=11). Of the RD patients, 53% did not require dose adjustments during treatment. Two RD patients had thrombus progression. A total of 25 patients ultimately completed therapy with RD.Conclusions

Future trials are warranted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of reduced dosing of enoxaparin to treat overweight and obese adolescents with VTE.Free full text

Reduced dosing of enoxaparin for venous thromboembolism in overweight and obese adolescents: a single institution retrospective review

Abstract

Background

The global obesity epidemic has created new challenges, including venous thromboembolisms (VTE) in obese adolescents. The data on whether to reduce the dose of low‐molecular heparin in obese adults is conflicting, and information on adolescent patients is scarce.

Objectives

Our primary goal was to describe dosing, anti‐Xa levels, and outcomes of overweight and obese adolescents who received reduced doses of enoxaparin at the initiation of therapy. The secondary goal was to compare their outcomes to overweight and obese adolescents who received standard 1 mg/kg dosing to determine if future trials for dose reduction are warranted.

Patients/Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of overweight and obese patients between the ages of 12 and 18 years old diagnosed with VTE who were treated with reduced dosing (RD) of enoxaparin, comparing their dosing, anti‐Xa levels, and outcomes to overweight and obese adolescents who received standard dosing (SD).

Results

RD patients (n=19) achieved therapeutic mean initial anti‐Xa levels that were similar to SD patients (n=11). Of the RD patients, 53% did not require dose adjustments during treatment. Two RD patients had thrombus progression. A total of 25 patients ultimately completed therapy with RD.

Conclusions

Future trials are warranted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of reduced dosing of enoxaparin to treat overweight and obese adolescents with VTE.

1. INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization has reported an obesity epidemic affecting many countries, even developing, poor nations.1 According to the Centers for Disease Control, the prevalence of obesity in the United States in the 12‐19 year age range has already nearly doubled from 10.5% (1988‐1994) to 20.6% (2013‐2014), while extreme obesity (defined as ≥ 120th percentile) has tripled from 2.6% (1988‐1994) to 9.1% (2013‐2014).2 Similar to obese adults, obese adolescents have a higher risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) compared to non‐obese adolescents.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 As the global obesity epidemic continues, there will be a greater need to treat overweight and obese adolescents for VTE. This population poses a dosing dilemma when prescribing low‐molecular‐weight heparins (LMWH)—commonly enoxaparin.

There is little data to guide providers on how to dose enoxaparin in overweight and obese adolescents. First, the recommendations by the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) for weight‐adjusted dosing of enoxaparin to treat pediatric VTE are based largely on adult studies, despite reduced predictability of the anticoagulant effect in children compared to adults when using weight‐adjusted dosing.8, 9 Thus, enoxaparin is used off label in children. Second, obesity can affect the pharmacokinetics of enoxaparin, although it is unclear if the net effects warrant dose modifications.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Third, the therapeutic ranges recommended by the College of American Pathologists have not been validated in clinical trials.15 Finally, the monitoring of enoxaparin utilizing anti‐Xa levels in adults is controversial, and no data exist for adolescents.16, 17

Adolescent VTE, most commonly deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), patterns and mortality rates are different compared to adult VTE.18 For example, PE in adolescents is rarely fatal and likely secondary to fewer comorbidities in the adolescent population.19 In addition, adult dose‐reduction strategies such as dose‐capping may not apply for an obese adolescent who weighs less.12, 13, 20 Because of these differences, data from obese adolescents is necessary and should not be extrapolated from trials designed for obese adults.

To our knowledge, there has been no study describing dose modifications in obese adolescents diagnosed with VTE. Two case series described enoxaparin prophylaxis in obese adolescents, not treatment.21, 22 The small numbers in those studies limit the interpretation of their enoxaparin pharmacokinetic data.

At our institution, the Pediatric Hematology/Oncology (PHO) team is consulted for all adolescent patients diagnosed with VTE. The initial dosing of enoxaparin is determined and ordered at a pediatric hematologist's discretion with some patients receiving doses less than the ACCP's recommendations. After approval by the institution's institutional review board, we performed a retrospective cohort study with the primary goal of describing dosing, anti‐Xa levels, and outcomes of overweight and obese adolescents who received upfront reduced dosing (RD) of enoxaparin. We also compared these patients to overweight and obese adolescents treated at our institution who received standard dosing (SD) to determine if future trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of dose reduction are warranted.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study population and data

Our PHO team, as directed by a pediatric hematologist, manages all aspects of care for adolescents diagnosed with VTE including dosing, anti‐Xa level monitoring, and follow‐up. Our PHO team maintains an internal database of any new patients we encounter, captured by new consultation notes and billing records, collecting the patients’ names, medical record numbers, dates of birth, and diagnoses.

This database was queried using the terms “thrombosis,” “thrombus,” “DVT,” “vein,” “clot,” “PE,” “pulmonary,” “emboli,” and “stroke.” The electronic and written medical records from hospitalization and/or outpatient follow‐ups were reviewed. Patients were included if they were ≥12 and ≤18 years old; overweight or obese, defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 85th percentile for age and sex23; and received enoxaparin for treatment of VTE between January 2004 and December 2014. Patients with renal disease—defined as having any pre‐existing renal diagnosis, undergoing dialysis, or carrying a diagnosis of acute renal failure described in the medical records—were excluded. Patients with cerebral venous thrombosis, or who had trauma or surgery within one week of VTE diagnosis, were excluded as the associated bleeding risk may have influenced the initial enoxaparin dose selected.

Data collected include demographics, BMI, radiology reports, laboratory data, enoxaparin doses and adjustments, anti‐Xa levels, and descriptions of any bleeding events. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated utilizing the creatinine–based bedside Schwartz equation.24 DVT and PE were diagnosed using duplex ultrasonography or venography and computed tomography angiogram, respectively.

SD was defined as ≥ 0.90 mg/kg every 12 hours. This cutoff was chosen to account for doses rounded down to the nearest 10 mg increment vial. RD was defined as any dose <0.90 mg/kg every 12 hours. The duration of anticoagulation treatment varied depending on the scenario (ie, spontaneous or provoked).25 Furthermore, the duration of enoxaparin used during the treatment time frame varied. As current VTE treatment recommends three months of therapy, the final dose (and final anti‐Xa level) in our study was defined as the last prescribed dose (and level) at 90 days of treatment.9

2.2. Anti‐Xa levels and dose adjustments

At our institution, anti‐Xa levels drawn after the 2nd through 5th doses at 3‐5 hours post‐dose are routinely obtained in all patients at the initiation of enoxaparin. In general, during outpatient follow‐up, anti‐Xa levels are obtained with any dose adjustment or monthly. Following ACCP guidelines, therapeutic target anti‐Xa level is between 0.5‐1.0 units/mL. Sub‐ and supra‐therapeutic levels are below and above this range, respectively.9

For this study, a dose adjustment was defined as a change of enoxaparin dose. The rationale for adjustment was determined by a review of the medical records. The Dade Behring BCS XP instrument (Marburg, Germany) was used for measurement of the anti‐Xa level, with Diagnostica Stago (Parsippany, NJ, USA) or Quest Diagnostics (Madison, NJ, USA) anti‐Xa chromogenic assays.

2.3. Outcomes

Retrospective reviews of radiology reports and medical records were performed to determine progression and bleeding, respectively. A progression was defined as thrombus extension, the development of a new PE, or re‐thrombosis in a previously treated site, occurring after the initiation of enoxaparin. Based on medical record descriptions, bleeding events occurring 24 hours after enoxaparin initiation were classified as major if they were associated with a decrease in hemoglobin of ≥2 g/dL within 24 hours of the bleeding event or resulted in a blood transfusion. Bleeding events that did not satisfy the criteria for major based on medical record descriptions, were classified as minor.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Summary statistics were calculated. Quantitative data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and nominal data as a percentage. A one sample goodness of fit test was used to compare the progression and bleeding rates of our sample relative to the mean rates reported in previous studies. Comparisons between the two groups (RD vs SD) for quantitative variables were performed using the t‐test, with the exception of the comparison of the number of anti‐Xa levels. As this variable was non‐normally distributed, the values were log‐transformed prior to the analysis. For nominal variables, the Fisher's Exact test was used. Significance was assessed at P<.05. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v. 22 (Armonk, NY, USA).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The initial database query resulted in 276 patients. Electronic and written medical record review resulted in 42 patients, 12 of which were excluded for cerebral venous thrombosis (4), recent trauma or surgery (3), or renal disease (5), leaving 30 patients in our study group. Twenty‐seven patients were hospitalized for initial VTE management. Of these 27 hospitalized patients, three were transferred from outside institutions on enoxaparin plus warfarin (2) or heparin infusion (1) at the time of transfer. After 4 weeks of hospitalization, one patient followed up with an outside institution for continued VTE management. Serum creatinine was available in 21 patients (range 0.53‐0.99 mg/dL); the estimated GFR was 97.12 mg/min/1.73 m2 (range 69.12‐143.50 mg/min/1.73 m2). Available unconjugated bilirubin levels (n=20), were below 6 mg/dL, the threshold shown to interfere with anti‐Xa level assays.26 Twenty‐nine patients were reportedly negative for antithrombin III deficiency.

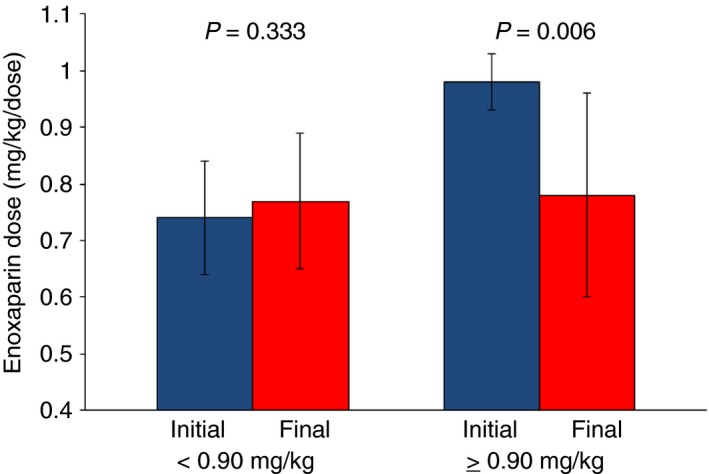

Nineteen patients initially received RD enoxaparin (Table 1). Mean initial anti‐Xa level was within therapeutic range and 14/19 (74%) had initial therapeutic or supra‐therapeutic anti‐Xa levels. Five patients had initial sub‐therapeutic anti‐Xa levels, one of whom tested positive for a lupus anticoagulant and had a thrombus progression. Of the 19 patients, 10 (53%) did not require any dose adjustments during treatment; 23 of 27 (85%) anti‐Xa levels obtained during their treatment were within therapeutic range. The mean initial and final doses were not significantly different (Figure 1). Four RD patients’ final doses were greater than their initial doses (Table 2). Of these four, two patients who were initially dosed at <0.7 mg/kg had thrombus progression despite one patient having an initial supra‐therapeutic anti‐Xa level. Two bleeding events occurred, both of which were minor (Table 1).

Table 1

Comparison of initial treatment dose groups

| All patients (n=30) | Initial treatment dose (mg/kg/dose) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.90 (RD) (n=19) | ≥0.90 (SD) (n=11) | |||

| Agea (years) | 15.3±1.6 | 15.3±1.4 | 15.4±2.1 | .940 |

| Male (%) | 36.7 | 31.6 | 45.5 | .696 |

| White (%) | 83.3 | 84.2 | 81.8 | >.999 |

| Weighta (kg) | 96.4±22.1 | 101.8±20.5 | 87.1±22.6 | .078 |

| Heighta (cm) | 171.3±10.2 | 172.4±10.3 | 169.5±10.2 | .464 |

| Obeseb (%) | 76.7 | 84.2 | 63.6 | .372 |

| DVTc | 36.7 (11) | 36.8 (7) | 36.4 (4) | >.999 |

| PEc | 26.6 (8) | 21.1 (4) | 36.4 (4) | .417 |

| DVT and PEc | 36.7 (11) | 42.1 (8) | 27.2 (3) | .466 |

| Thrombolysis at diagnosisc | 33.3 (10) | 36.8 (7) | 27.3 (3) | .702 |

| Initial dosea (mg/kg) | 0.83±0.14 | 0.74±0.10 | 0.98±0.05 | <.001 |

| Range (mg/kg) | (0.58‐1.04) | (0.58‐0.88) | (0.90‐1.04) | – |

| Initial anti‐Xa levela (units/mL) | 0.70±0.23 | 0.68±0.20 | 0.73±0.28 | .640 |

| Sub‐therapeutic (<0.5)c | – | 26.3 (5) | 18.2 (2) | >.999 |

| Therapeutic (0.5‐1.0)c | – | 68.4 (13) | 72.7 (8) | >.999 |

| Supra‐therapeutic (>1.0)c | – | 5.3 (1) | 9.1 (1) | >.999 |

| Median number of anti‐Xa levelsd | – | 3 | 4 | .404 |

| Range | – | (1‐8) | (1‐14) | – |

| Patients who required dose adjustmentsc | – | 47.4 (9) | 81.8 (9) | .063 |

| Final dosea (mg/kg) | 0.77±0.14 | 0.77±0.12 | 0.78±0.18 | .829 |

| Range (mg/kg) | (0.56‐1.13) | (0.56‐1.01) | (0.56‐1.13) | – |

| Final dose > initial dosec | – | 21.0 (4) | 9.1 (1) | .626 |

| Final dose < initial dosec | – | 21.0 (4) | 72.7 (8) | .009 |

| Progressionc | – | 10.5 (2) | 9.1 (1) | >.999 |

| Bleeding (all events were minor)c | – | 10.5 (2) | 27.3 (3) | .327 |

DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; RD, reduced dose enoxaparin; SD, standard dose enoxaparin.

P values refer to comparisons between RD group and SD group.

Mean±standard deviation initial (blue) and final dosing (red) for the two study groups. Patients dosed initially at <0.90 mg/kg (RD) did not significantly increase their dose, while patients dosed at ≥0.90 mg/kg (SD) significantly decreased their dose to maintain anti‐Xa levels within therapeutic range (0.5‐1.0 units/mL)

Table 2

Outcomes for reduced dose patients whose final dose was greater than their initial dose

| Weight (kg) | BMI (percentile) | Indication | Initial dose (mg/kg) | Final dose (mg/kg) | Initial anti‐Xa level (units/mL) | Final anti‐Xa level (units/mL) | Reason for dose adjustment(s) | Number of dose adjustments (n) | Progression or recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 112.3 | 97 | PE | 0.71 | 0.89 | 0.35 | 0.81 | Sub | 1 | No |

| 98.1 | 97 | DVT | 0.61 | 0.82 | 1.08 | 0.64 | Progression | 4 | Yes |

| 97.6 | 98 | PE | 0.61 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 0.69 | Physician discretion | 2 | No |

| 89.2 | 94 | DVT, IVC extension | 0.67 | 1.01 | 0.47 | 1.62 | Sub;Progression | 6+ | Yes |

BMI, body mass index; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; IVC, inferior vena cava; Sub, sub‐therapeutic anti‐Xa level <0.5 units/mL.

Progression is defined as thrombus extension, the development of PE that was not present at diagnosis, or re‐thrombosis in a previously treated site after initiation of enoxaparin and prior to completing therapy.

Eleven patients received SD (Table 1). Unlike the RD patients, the SD patients’ mean final dose was significantly lower than their mean initial dose (Figure 1). Notably, in eight patients whose final doses were less than their initial doses, six (75%) were dose reduced secondary to supra‐therapeutic anti‐Xa levels obtained 2‐16 days from initiation of therapy.

Between the two groups, no significant differences were observed in demographics, obesity status, type of VTE, and use of thrombolysis (Table 1). Despite a significantly lower mean initial dose in the RD group compared to the SD group, the mean initial anti‐Xa levels and mean final doses were similar between the groups (Table 1). There were no significant differences in the percentages of patients who had initial sub‐therapeutic, therapeutic, or supra‐therapeutic anti‐Xa levels, the number of anti‐Xa levels obtained during 90 days of treatment, nor in progression or bleeding rates between the two groups (Table 1).

In prior LMWH studies, the reported incidence of progression ranged from 1‐7%27, 28, and the reported incidence of bleeding ranged from 0‐36%.27, 29 Utilizing a mean incidence of approximately 5% for progression, and 20% for minor bleeding, our RD and SD groups did not differ significantly with these mean rates (progression: RD vs 5% P=.25; SD vs 5% P=.43, bleeding: RD vs 20% P=.40, SD vs 20% P=.47).

Ultimately, 83% of all patients were on RD at the end of treatment or at 90 days from diagnosis (n=25, mean dosing 0.73 ± 0.11 mg/kg), with therapeutic or supra‐therapeutic anti‐Xa levels.

These findings suggest that initial doses calculated using actual body weight may be greater than what is needed, which is consistent with some previously published reports.12, 13, 26 Therapeutic or supra‐therapeutic anti‐Xa levels were achieved in 74% of the RD group. However, the degree of dose reduction should be cautiously considered as the two RD progressions occurred in patients who were initially dosed at <0.7 mg/kg.

Though the role of anti‐Xa monitoring for enoxaparin in adult is controversial, monitoring in our SD patients showed supra‐therapeutic levels up to 16 days from the initial dose. The significance of this is unknown as our sample size is small, but may be secondary to the effects that obesity has on enoxaparin pharmacokinetics that have yet to be clearly defined.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Until there are more studies regarding the utility of anti‐Xa levels, overweight individuals should have periodic monitoring, possibly during the first 2 weeks of therapy.16, 17

All bleeding events in our study were minor. Compared to the RD group, the SD group had a higher percentage. This is more likely secondary to the small sample size and less likely secondary to overdosing in the SD group; two of the three SD group patients had therapeutic anti‐Xa levels during the bleeding events.

Limitations inherent to retrospective cohort studies at a single institution pertain to this preliminary study. Furthermore, outpatient factors such as injection methods or timing of anti‐Xa level testing are confounding variables. The small sample size precludes any conclusions regarding efficacy and safety. Nonetheless, as obesity rates increase globally, future trials are warranted to evaluate reduced dose enoxaparin in the treatment of overweight and obese adolescents with VTE. The information reported here offers a beginning for that research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S. Hoffman and C. Braunreiter contributed to the research design, data collection and analysis, and manuscript writing.

RELATIONSHIP DISCLOSURE

The authors have no funding sources or conflicts of interest to disclose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Beth Sandon‐Kleiboer for her help with data collection and Alan T. Davis, PhD, and Tracy J. Koehler, PhD, for assistance with statistical support and manuscript preparation. The authors also thank Beyond Words, Inc., for assistance with the editing and preparation of this manuscript. The authors maintained control over the direction and content of this article during its development. Although Beyond Words, Inc., supplied professional writing and editing services, this does not indicate its endorsement of, agreement with, or responsibility for the content of the article.

Notes

Hoffman S, Braunreiter C. Reduced dosing of enoxaparin for venous thromboembolism in overweight and obese adolescents: a single institution retrospective review. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2017;1:188–193. 10.1002/rth2.12032 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES

Articles from Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis are provided here courtesy of Elsevier

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Use of Real-World Data and Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling to Characterize Enoxaparin Disposition in Children With Obesity.

Clin Pharmacol Ther, 112(2):391-403, 18 May 2022

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 35451072 | PMCID: PMC9504927

Reduced dosing of enoxaparin for venous thromboembolism in overweight and obese adolescents: a single institution retrospective review.

Res Pract Thromb Haemost, 1(2):188-193, 10 Aug 2017

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 30046689 | PMCID: PMC6058273

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Evaluating Adequacy of VTE Prophylaxis Dosing with Enoxaparin for Overweight and Obese Patients on an Orthopedic-Medical Trauma Comanagement Service.

South Med J, 116(4):345-349, 01 Apr 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37011582

Association of Anti-Factor Xa-Guided Dosing of Enoxaparin With Venous Thromboembolism After Trauma.

JAMA Surg, 153(2):144-149, 01 Feb 2018

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 29071333 | PMCID: PMC5838588

Achievement of goal anti-Xa activity with weight-based enoxaparin dosing for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in trauma patients.

Pharmacotherapy, 41(6):508-514, 07 May 2021

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 33864688

Increased Enoxaparin Dosing for Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis in General Trauma Patients.

Ann Pharmacother, 51(4):323-331, 15 Dec 2016

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 28228055

Review

2

,

3

2

,

3