Abstract

Background and objectives

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modelling has evolved to accommodate different routes of drug administration and enables prediction of drug concentrations in tissues as well as plasma. The inhalation route of administration has proven successful in treating respiratory diseases but can also be used for rapid systemic delivery, holding great promise for treatment of diseases requiring systemic exposure. The objective of this work was to develop a PBPK model that predicts plasma and tissue concentrations following inhalation administration of the PI3Kδ inhibitor nemiralisib.Methods

A PBPK model was built in GastroPlus® that includes a complete mechanistic description of pulmonary absorption, systemic distribution and oral absorption following inhalation administration of nemiralisib. The availability of clinical data obtained after intravenous, oral and inhalation administration enabled validation of the model with observed data and accurate assessment of pulmonary drug absorption. The PBPK model described in this study incorporates novel use of key parameters such as lung systemic absorption rate constants derived from human physiological lung blood flows, and implementation of the specific permeability-surface area product per millilitre of tissue cell volume (SpecPStc) to predict tissue distribution.Results

The inhaled PBPK model was verified using plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid concentration data obtained in human subjects. Prediction of tissue concentrations using the permeability-limited systemic disposition tissue model was further validated using tissue concentration data obtained in the rat following intravenous infusion administration to steady state.Conclusions

Fully mechanistic inhaled PBPK models such as the model described herein could be applied for cross molecule assessments with respect to lung retention and systemic exposure, both in terms of pharmacology and toxicology, and may facilitate clinical indication selection.Free full text

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modelling of Inhaled Nemiralisib: Mechanistic Components for Pulmonary Absorption, Systemic Distribution, and Oral Absorption

Abstract

Background and Objectives

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modelling has evolved to accommodate different routes of drug administration and enables prediction of drug concentrations in tissues as well as plasma. The inhalation route of administration has proven successful in treating respiratory diseases but can also be used for rapid systemic delivery, holding great promise for treatment of diseases requiring systemic exposure. The objective of this work was to develop a PBPK model that predicts plasma and tissue concentrations following inhalation administration of the PI3Kδ inhibitor nemiralisib.

Methods

A PBPK model was built in GastroPlus® that includes a complete mechanistic description of pulmonary absorption, systemic distribution and oral absorption following inhalation administration of nemiralisib. The availability of clinical data obtained after intravenous, oral and inhalation administration enabled validation of the model with observed data and accurate assessment of pulmonary drug absorption. The PBPK model described in this study incorporates novel use of key parameters such as lung systemic absorption rate constants derived from human physiological lung blood flows, and implementation of the specific permeability-surface area product per millilitre of tissue cell volume (SpecPStc) to predict tissue distribution.

Results

The inhaled PBPK model was verified using plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid concentration data obtained in human subjects. Prediction of tissue concentrations using the permeability-limited systemic disposition tissue model was further validated using tissue concentration data obtained in the rat following intravenous infusion administration to steady state.

Conclusions

Fully mechanistic inhaled PBPK models such as the model described herein could be applied for cross molecule assessments with respect to lung retention and systemic exposure, both in terms of pharmacology and toxicology, and may facilitate clinical indication selection.

Key Points

| For a complete mechanistic description of inhalation administration, a PBPK model should include pulmonary absorption, systemic distribution and oral absorption. |

| Currently, inhalation modelling strategies need to include a way of determining key parameters that cannot be either directly predicted from in vitro data or interpolated from clinical data; for example, the systemic absorption rate constants from the lung. |

| Verification of a complete mechanistic model of inhalation administration requires intravenous, oral and inhalation systemic PK data, in addition to concentrations at the site of administration in the lung. |

Introduction

The inhalation route of administration is frequently chosen for the treatment of patients with respiratory diseases as it delivers the therapeutic compound directly to the target organ while resulting in a lower systemic exposure. Delivering compound directly to an inflamed or affected disease microenvironment has proven to be of greater benefit to the patient and lowers the risk of unwanted adverse effects in other organs [1]. However, the inhalation route of administration can also be used for rapid systemic delivery due to low metabolism and high bioavailability [2].

Nemiralisib (GSK2269557) is a potent PI3Kδ inhibitor that has been investigated for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other respiratory diseases based on its effects on neutrophils, T cells and B cells [3–7]. Nemiralisib and other PI3Kδ inhibitors are also potent inhibitors of regulatory T cells and could therefore play a role in the treatment of cancer, in particular to enhance the effect of checkpoint inhibitors [8–12]. Oncology patients are often treated at the point of advanced disease with metastasis in multiple organs [13], and hence an effective therapeutic would most likely require inhibition of regulatory T cells in multiple organs. Choices with respect to optimal route of administration are therefore a careful balance between effective delivery of compound to the target organ (or specific cells residing within the organ) and potential adverse effect profiles of oral versus inhaled treatment. Most PI3Kδ inhibitors thus far have been developed as oral compounds, with a few exceptions, including nemiralisib.

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modelling enables the prediction of drug concentrations in tissues and plasma [14]. In fact, the development of tissue composition models to predict the tissue partition coefficients of compounds prior to the existence of PK data was a major enhancement facilitating the increased use and application of PBPK modelling in drug research and development [15]. PBPK modelling has evolved to include routes of drug administration such as application via skin and lung [16], with the lung being included in the commercial PBPK platform GastroPlus® in 2010 [17, 18].

The aim of the work described in this paper was to use PBPK modelling to evaluate whether nemiralisib distributes to tissues distal to the lung following inhalation administration in human. Using the PBPK platform GastroPlus and data derived from a clinical absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) study [19], mechanistic models describing inhalation administration, systemic distribution and oral absorption were constructed. The model was then verified with data from a clinical trial in which patients were treated with inhaled nemiralisib [3]. The predictions of tissue concentrations were subsequently verified with data from a rat tissue distribution study [20]. The inhaled PBPK model described herein is fully mechanistic and builds on a model previously published [21]. Moreover, the model described here offers a novel way of parameterising the pulmonary absorption component using systemic absorption rate constants from the lung based on lung blood flows, as well as the direct use of in vitro permeability from MDCK-MDR1 cells as an input for lung permeability, and fraction unbound in plasma as a surrogate for lung binding. The work described in this manuscript offers a new approach for mechanistic modelling following inhalation administration.

Materials and Methods

Clinical and Preclinical Study Designs

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion Study

A previously published clinical trial (NCT03315559) was designed to characterise the human absorption, metabolism, excretion and pharmacokinetics of the inhaled drug nemiralisib using an intravenous microtracer, when combined with an inhalation dose and an oral radiolabel dose [19]. Briefly, healthy male subjects underwent two treatment periods with a 14-day washout between treatments. In treatment period 1, subjects inhaled 1000 µg of non-radiolabelled nemiralisib as a dry powder from the ELLIPTA® inhaler device, and within 5 min received 10 µg [14C]nemiralisib (approximately 22.2 kilo Becquerel [kBq]; 0.6 micro Curie [µCi]) via an intravenous infusion over 15 min. In treatment period 2, subjects were administered 800 µg of [14C]nemiralisib (1850 kBq; 50 µCi) as an oral solution in water. Blood samples were collected for a minimum of 168 h and up to 336 h after dosing [19].

Inhalation Study

A previously published phase I clinical trial PII116617 (NCT01762878) explored the PK/PD relationship of nemiralisib in a single-dose escalation design [3]. Briefly, regular cigarette smokers underwent a four-way crossover, with each subject receiving placebo, 0.1, 0.5, and 2 mg of a dry powder formulation of nemiralisib administered using the Diskus® device, with a 14-day washout between treatments. A 14-day repeat-dose arm was conducted in a further cohort where the subjects received 2 mg of nemiralisib or placebo in a parallel group design, also delivered as a dry powder formulation using the Diskus device. In addition to blood samples, bronchoscopy for the collection of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples was performed at 24 h (trough) after the final (day 14) dose [3].

Tissue Distribution in Rat

To investigate the tissue distribution of nemiralisib in the conscious male rat, nemiralisib (GSK2269557B HCl salt form) was infused over 25 h via intravenous administration to three male CD Sprague–Dawley rats, after which time blood, liver, kidney, spleen, muscle, lung and skin were sampled after the animals were sacrificed. The dose level of 0.24 mg/kg/h was selected to achieve steady-state plasma concentrations of approximately 100 ng/mL, and tissue concentrations of approximately 1000–5000 ng/mL based on a rat PBPK model incorporating historical rat PK data. Concentrations of nemiralisib in plasma and the specified tissues, accounting for residual plasma concentrations, were then determined, following sample preparation, including tissue homogenisation and protein precipitation, via liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS).

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modelling

GastroPlus version 9.7 (Simulations Plus Inc., Lancaster, CA, USA) with the nasal-pulmonary additional dosage route module was used for the PBPK modelling and simulation. In addition, MembranePlus® version 2.0 (Simulations Plus Inc.) was used to predict enterocyte drug binding in the gastrointestinal tract and ADMET Predictor® v9.0 (Simulations Plus Inc.) was used to predict other input parameters as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1

Key physicochemical/pharmacokinetic properties used as inputs for the PBPK predictions

| Parameter | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| logP | 4.01 | Measured |

| pKa values | Acid 12.72 | ADMET Predictor v9.0.0.0 |

| Acid 11.26 | ADMET Predictor v9.0.0.0 | |

| Base 8.47 | Measured | |

| Base 2.78 | ADMET Predictor v9.0.0.0 | |

| Base 2.22 | ADMET Predictor v9.0.0.0 | |

| Base 1.35 | ADMET Predictor v9.0.0.0 | |

| Solubility (mg/mL) | 1.0E-3 at pH 10 | Measured |

| Bile salt effect solubilisation ratio | 2.82E+4 | From measured FaSSIF and FeSSIF solubility |

| Mean precipitation time (s) | 900 | GastroPlus default |

| Diffusion coefficient (cm2/s × 105) | 0.6 | ADMET Predictor v9.0.0.0 |

| Drug particle density (g/mL) | 1.2 | GastroPlus default |

| Particle radius (μm) | PL: Powder = 1 | Measured |

| Human Peff (cm/s × 10−4) | 0.26–0.46 | Fitted to PO PK data |

| Gut physiology | Human-physiological-fasted | GastroPlus default |

| Absorption model ASFs (cm−1) | Duodenum = 2.625 | GastroPlus Human-physiological-fasted Opt logD model SA/V 6.1 with ASF coefficient C3 = 0 as described in the Results section |

| Jejunum 1 = 2.630 | ||

| Jejunum 2 = 2.620 | ||

| Ileum 1 = 2.601 | ||

| Ileum 2 = 2.606 | ||

| Ileum 3 = 2.587 | ||

| Caecum = 0 | ||

| Ascending colon = 0 | ||

| Intestinal FPE | 17% | Based on clinical data in the study by Harrell et al. [19] |

| % Unbound enterocytes | 6.5 | MembranePlus v2.0 |

| Human BPR | 0.94 | Measured |

| Rat BPR | 1.42 | Measured |

| Human FuP (%) | 2.1 | Measured |

| Rat FuP (%) | 2.4 | Measured |

| Kp prediction method | Lukacova with lysosomes (see GastroPlus Manual) Poulin-extracellular (Eq. 4 in the study by Poulin and Theil [27]) | Perfusion-limited model Permeability-limited model (Fu intracellular method = S+ v9.5 w/Lys; (see GastroPlus Manual) |

| Human specific PStc (mL/s/mL) | 0.175 | Fitted |

| Systemic clearance (L/h) | 7.518–20.040 | Derived from NCA of intravenous PK |

| Inhaled parameters: | ||

| %Deposited in extrathoracic | 19.147 | Exhaled = 50.6%, which is in line with the proportion of drug (approximately 46%) unaccounted for in the study by Harrell et al. [19] |

| %Deposited in thoracic | 8.676 | |

| %Deposited in bronchiolar | 2.188 | |

| %Deposited in alveolar-interstitial | 19.392 | |

| Pulmonary solubility (mg/mL) | 0.22 | Measured |

| Permeability (cm/s) for each region | 1.57E−5 | Measured (MDCK-MDR1 cells) used directly |

| Systemic absorption rate Constant (1/s) | Estimated from lung blood flows Measured Fup (except AI = 100%) Measured Fup | |

| Extrathoracic | 4.325E−3 | |

| Thoracic | 4.325E−3 | |

| Bronchiolar | 4.325E−3 | |

| Alveolar-Interstitial | 0.173 | |

| % Unbound in mucus | 2.1 | |

| % Unbound in cell | 2.1 |

ASF absorption scale factor, BPR blood/plasma ratio, FaSSIF fasted state simulated intestinal fluid, FeSSIF fed state simulated intestinal fluid, FPE first-pass extraction, FuP fraction unbound in plasma, Kp tissue:plasma partition coefficient, MDCK-MDR1 Madin Darby Canine Kidney cells transfected with the human MDR1 gene, NCA non-compartmental analysis, PBPK physiologically based pharmacokinetic, Peff effective human jejunal permeability, PK pharmacokinetic, PL pulmonary, PO oral, PStc permeability-surface area product, SA/V surface area-to-volume ratio

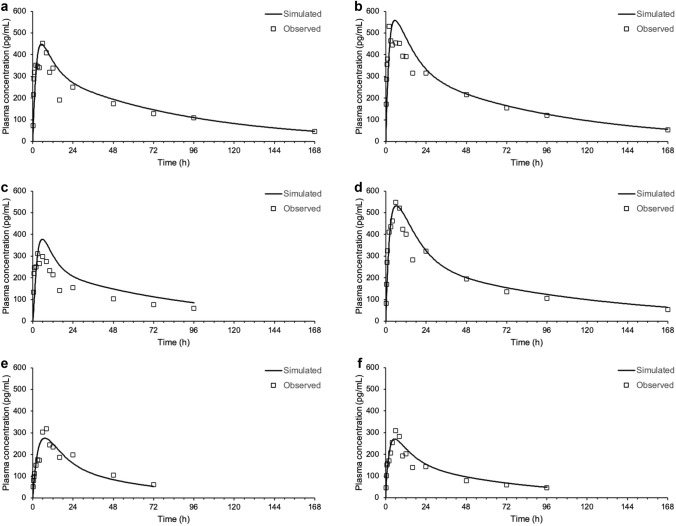

Diagrams of the individual components comprising the PBPK model can be seen in Fig. 1. The simulation of inhalation administration requires an accurate description of drug deposition, absorption from different lung regions, absorption of the swallowed portion from the intestine, and systemic distribution and clearance, each of which are described below.

Conceptual diagram of an inhaled + oral (ACAT) + systemic (tissues) PBPK model. ACAT advanced compartmental absorption and transit, PBPK physiologically based pharmacokinetic, PStc permeability-surface area product, Q tissue blood flow, V tissue volume

Systemic Disposition

Initial models to describe systemic distribution following intravenous administration were built using a perfusion-limited tissue model for nemiralisib; this is the default model in GastroPlus as it only requires tissue-to-plasma partition coefficients (Kp values) that can be predicted from drug-specific physicochemical properties [14]. Due to the need to more accurately predict the maximum concentration (Cmax) following intravenous administration in humans, a permeability-limited tissue model for nemiralisib was employed; this requires a permeability-surface area product (PStc) [14] and the specific PStc (PStc per millilitre of tissue cell volume) implemented in GastroPlus was used. Subsequently, a permeability-limited tissue model was used to assess the accuracy of tissue-to-plasma concentration ratio (Rtp) predictions in the rat following intravenous dosing.

Systemic clearance for nemiralisib in human from the intravenous microtracer data observed in the ADME trial (NCT03315559) [19] was used directly in the simulations.

As nemiralisib is a basic compound, it is expected to interact with tissue acidic phospholipids [22]. In GastroPlus, the human tissue acidic phospholipid concentrations are generally assumed to be the same as the rat, therefore the values were updated with those for human specified in the SimcypTM Simulator version 18 (Certara, Sheffield, UK).

Oral Absorption

The advanced compartmental absorption and transit (ACAT) model [23] was used to describe oral absorption, including the swallowed portion of an inhalation dose. The ACAT model divides the gastrointestinal tract into nine compartments, from the stomach to the ascending colon. The Opt-logD SA/V version 6.1 was used to predict the absorption scale factors (ASF) describing regional permeability in each of the nine compartments.

For the purpose of obtaining individual permeability values, a compartmental systemic disposition model was fitted for each individual using their respective intravenous data; those permeabilities were subsequently used with a systemic PBPK model. Liver first-pass extraction (FPE), also known as hepatic extraction (Eh), was calculated from the intravenous clearance for each individual, assuming a liver blood flow of 90 L/h. In the nemiralisib clinical study 206764 (NCT03315559), Fg (fraction escaping gut wall metabolism) was reported as 0.83 [19], and intestinal FPE for the model was accordingly set at 17%. The P450 enzyme predominantly responsible for the metabolism of nemiralisib is P4503A4 [21], but it was not specified in the model.

To achieve the best prediction of the oral plasma concentration profile, the effective permeability was manually fitted for each individual.

Pulmonary Absorption

The nasal-pulmonary additional dosage route module, used to model pulmonary absorption following inhalation dosing, has been described previously [17, 18]. Briefly, the model describes the lung as a collection of up to five compartments: an optional nose (containing the anterior nasal passages), extrathoracic (nasopharynx and oropharynx and the larynx), thoracic (trachea and bronchi), bronchiolar (bronchioles and terminal bronchioles) and alveolar-interstitial (respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts and sacs, and interstitial connective tissue). Following deposition, the disposition of the drug in the lung is dictated by mucociliary transit, swallowing from the extrathoracic compartment, dissolution in mucus, absorption into pulmonary cells and eventually into systemic circulation, accounting for fractions unbound in the mucus/surfactant layers and the cells.

Initial predictions for the deposition of nemiralisib following inhalation administration were obtained using the Multiple Path Particle Dosimetry (MPPD) model version 2.92.5 (Applied Research Associates, Raleigh, NC, USA) [24]. The model combines cascade impaction data, lung geometry and inhalation profiles as input parameters to predict the regional lung deposition. The ratio of predicted regional lung deposition was maintained, but the absolute values were subsequently adjusted using the fraction of dose absorbed from the lung (29%) following an inhalation dose as determined from GSK study number 206764 (NCT03315559) [19]. Deposition is a patient-specific factor [17] but has been assumed to be the same for all individuals in the modelling.

Pulmonary solubility was measured in simulated lung fluid and used directly. Fraction unbound in plasma was used as a surrogate for mucus and lung binding.

Nemiralisib-specific measured in vitro permeability from MDCK-MDR1 cells was used directly as the input for lung permeability instead of the default GastroPlus values based on rat alveolar permeability for a small set of hydrophilic non-electrolytes.

The systemic absorption rate constants from the lung cells into blood were estimated from human physiological lung blood flows, assuming that compound-specific parameters such as permeability, the rate of drug diffusion between lung fluid and lung cells, and fraction unbound in cells would account for lung retention. Specifically:

Human cardiac output (CO) = 5200 mL/min [25]

Bronchial regional blood flow = 2.5% CO [25]

Pulmonary blood volume ~ 500 mL [26]

5200 mL/min / 500 mL = 10.4 min−1 = 0.173 s−1 for pulmonary circulation

2.5% of 0.173/s = 4.325 × 10−3/s for bronchial circulation, and all other compartments.

Tissue Distribution in Rat

The nemiralisib plasma concentration versus time profile and associated tissue distribution in rat following intravenous infusion administration to steady state were prospectively predicted using a permeability-limited tissue model with the observed systemic clearance (0.568 L/h) and fitted specific PStc (0.8 mL/s/mL) from an earlier rat intravenous bolus administration PK study. On completion of the intravenous infusion administration study, retrospective analysis of the prediction was undertaken to assess the suitability of the systemic clearance and specific PStc.

Results

Systemic Distribution

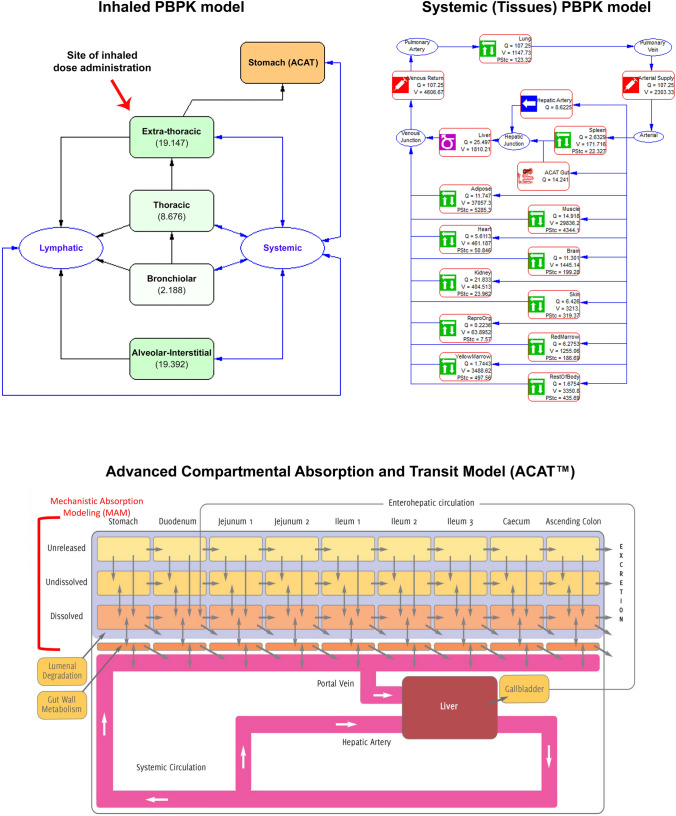

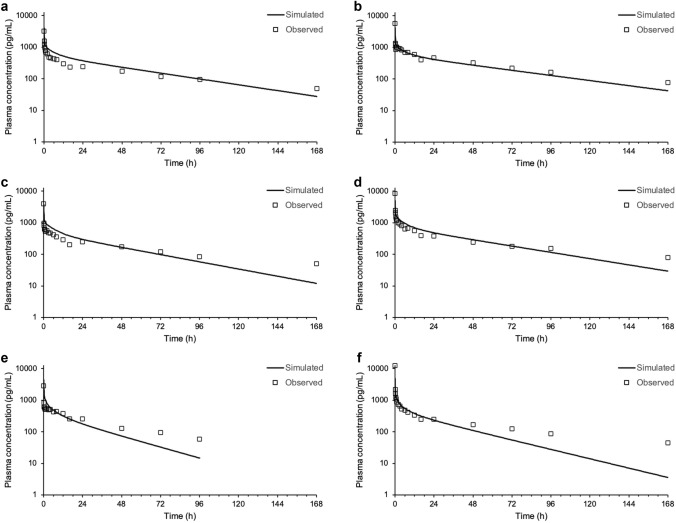

The plasma concentration versus time profile of nemiralisib in human is adequately predicted following intravenous dosing using a permeability-limited tissue model, in combination with the observed systemic clearance (Fig. 2). A specific PStc of 0.175 mL/s/mL was used for all subjects and all tissues, except the liver. A higher PStc was required in the liver to match the observed systemic clearance, and this tissue was set as perfusion-limited, clearly differentiating it from other tissues and enabling direct use of the observed systemic clearance value as an input for each subject.

Simulated plasma concentrations (solid line) following an intravenous infusion dose of approximately 10 μg compared with measured concentrations (symbols) in individual healthy volunteers (a–f represent subjects 1–6, respectively)

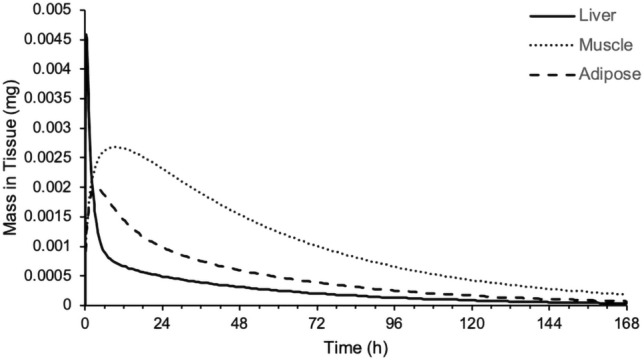

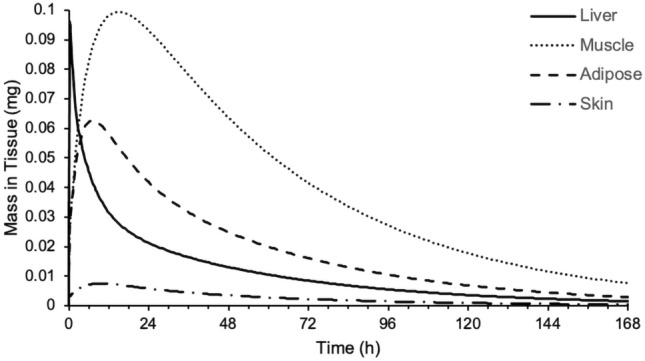

An assessment of the mass versus time profiles for the various tissues in the PBPK model highlighted that the liver, muscle and adipose are important tissues in terms of the distribution of nemiralisib (Fig. 3).

Oral Absorption

A reference solubility of 1 μg/mL at pH 10 was used, and, in combination with the pKa values and solubility factor, gave an adequate description of the change in buffer solubility with respect to pH (data not shown). The bile salt effect salt solubilisation ratio was fitted at 2.82E+4 using measured fasted state simulated intestinal fluid (FaSSIF) and fed state simulated intestinal fluid (FeSSIF) solubility data.

Effective permeability was predicted to be moderate from structure (1.04 × 10−4 cm/s) by ADMET Predictor, but had to be lowered to 0.26–0.46 × 10−4 cm/s to fit the individual oral plasma concentration versus time profiles of nemiralisib in human.

Initial predictions overpredicted the absorption post the time of maximum plasma concentration (tmax) of 6 h, with the total absorption from the caecum and ascending colon predicted to be substantial at approximately 40%. This overprediction was corrected by setting the ASF coefficient C3 in the ASF model to zero.

Simulations predicted a fraction absorbed of 44–63%, with 37–56% excreted as dissolved drug. Furthermore, the plasma concentration versus time profile of nemiralisib in human is adequately predicted following oral dosing (Fig. 4).

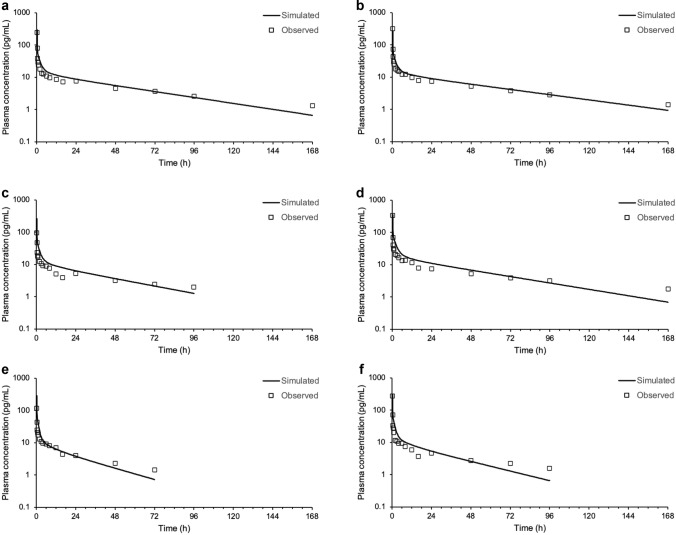

Pulmonary Absorption

The plasma concentration versus time profiles of nemiralisib in human are adequately predicted following inhalation dosing using a permeability-limited tissue systemic distribution PBPK model, combined with an ACAT model for oral absorption and a nasal-pulmonary mechanistic model for lung absorption (Fig. 5 and Table 2). Most of the systemic exposure is predicted to be from pulmonary absorption (29%), but there is a contribution from the swallowed portion of around 10%. The majority of the 10% swallowed portion is from the 19% of the inhalation dose initially deposited in the extrathoracic compartment, with an additional small percentage resulting from the ensuing mucociliary transit of dose deposited lower down the lung. The remaining 9% of the inhalation dose initially deposited in the extrathoracic compartment is excreted from the gastrointestinal tract as dissolved drug.

Predicted plasma concentrations (solid line) following an inhalation dose of approximately 1000 μg compared with measured concentrations (symbols) in individual healthy volunteers (a–f represent subjects 1–6, respectively)

Table 2

Predicted versus observed AUCt and Cmax following an inhalation dose of nemiralisib

| Subject | Predicted AUCt (pg h/mL) | Observed AUCt (pg h/mL) | AUCt Fold error | Predicted Cmax (pg/mL) | Observed Cmax (pg/mL) | Cmax Fold error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1001 | 3.324E+4 | 2.528E+4 | + 1.3 | 4551 | 3237 | + 1.4 |

| 1002 | 3.876E+4 | 4.477E+4 | − 1.2 | 4477 | 5609 | − 1.3 |

| 1003 | 2.562E+4 | 2.419E+4 | + 1.1 | 4330 | 3903 | + 1.1 |

| 1004 | 4.265E+4 | 4.042E+4 | + 1.1 | 5690 | 8283 | − 1.5 |

| 1005 | 1.500E+4 | 1.834E+4 | − 1.2 | 4813 | 2866 | + 1.7 |

| 1006 | 1.952E+4 | 2.708E+4 | − 1.4 | 4924 | 1.257E+4 | − 2.6 |

AUCt area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time zero to time t, Cmax maximum concentration

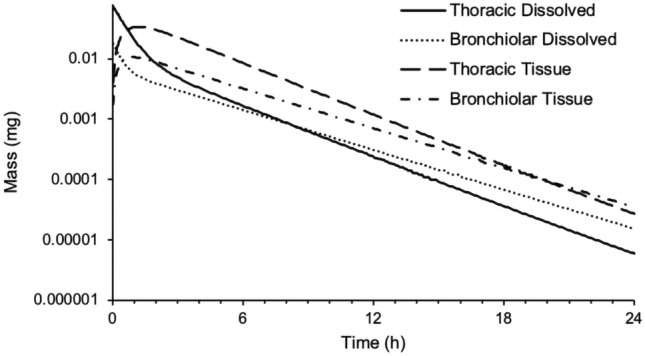

Retention of nemiralisib in lung is depicted in Fig. 6. Nemiralisib is predicted to be slowly absorbed from the thoracic and bronchiolar compartments over 20 h. As can be seen from Fig. 7, significant amounts of nemiralisib are predicted, by PBPK modelling, to distribute into tissues following inhalation administration, thus contributing to its long half-life.

Predicted mass of nemiralisib in thoracic mucus (solid line), bronchiolar mucus (dotted line), thoracic tissue (dashed line) and bronchiolar tissue (dashed/dotted line) versus time in human following an inhalation dose of approximately 1000 μg in a single healthy volunteer

Predicted mass of nemiralisib in liver (solid line), muscle (dotted line), adipose (dashed line) and skin (dashed/dotted line) versus time following an inhalation dose of approximately 1000 μg in a single healthy volunteer using a permeability-limited tissue model

A 14-day repeat once-daily 2 mg dose simulation predicted that at 24 h (trough) after the final dose (day 14), the plasma concentration of nemiralisib would be 2.3 ng/mL and the dissolved mucus concentrations in the thoracic and bronchiolar compartments would be 43 and 25 ng/mL, respectively.

Tissue Distribution in Rat

Generally, predicted Kp values can be deemed accurate if they agree with experimental values within a factor of three [22]. As can been seen in Table 3, using a permeability-limited tissue model with the specific PStc (0.8 mL/s/mL) fitted against plasma data from an earlier intravenous bolus administration PK study, adequately predicted the Rtp values for liver, kidney, spleen, muscle, lung and skin (calculated by dividing the predicted tissue concentration by the plasma concentration). For model accuracy, the observed clearance of 0.71 L/h from the tissue distribution study was used instead of the value from the earlier intravenous bolus study of 0.568 L/h.

Table 3

Predicted and measured rat tissue-to-plasma concentration ratios

| Tissue | Prospectively predicted Rtp | Measured Rtp | Prospective Fold error | Retrospectively predicted Rtp | Retrospective Fold error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | 18.2 | 23.0 | − 1.3 | 18.2 | − 1.3 |

| Kidney | 51.2 | 60.5 | − 1.2 | 24.1 | − 2.5 |

| Spleen | 28.7 | 11.5 | + 2.5 | 13.6 | + 1.2 |

| Muscle | 11.9 | 3.5 | + 3.4 | 8.8 | + 2.5 |

| Lung | 41.3 | 11.4 | + 3.6 | 13.9 | + 1.2 |

| Skin | 10.3 | 7.7 | + 1.3 | 6.9 | − 1.1 |

The predicted liver Rtp remains the same as it was defined as a perfusion-limited tissue, i.e. it did not use the specific PStc in the prediction

Rtp rat tissue-to-plasma concentration ratio, PStc permeability-surface area product

The impact of the specific PStc was assessed by manually adjusting the value to get the best ‘fit’ of Rtp values. A specific PStc of 0.11 mL/s/mL was determined to give the best overall prediction across the tissues. Interestingly, this specific PStc value is similar to the fitted human value of 0.175 mL/s/mL (Table 3).

Discussion

With PBPK modelling constantly evolving, it is now possible to include the lung as a route of drug administration and to predict plasma drug concentrations as well as concentrations in tissues. Nemiralisib is a potent inhaled PI3Kδ inhibitor that has been investigated for the treatment of COPD [3]. Based on its mechanism of action, in particular its well-described inhibition of regulatory T cell function, nemiralisib could potentially play a role in the treatment of cancer; however, to achieve therapeutic impact, distribution to tissues distant from the lung following inhalation administration would be required. This manuscript describes a PBPK model in GastroPlus that includes a complete mechanistic description of pulmonary absorption and systemic distribution following inhalation administration of nemiralisib, thus enabling prediction of tissue concentrations. Predicted concentrations at the site of administration were verified against clinical BAL data and predicted systemic tissue concentrations were verified against a rat tissue distribution study. The inhaled modelling strategy employed here could be a useful tool for assessing lung retention and systemic exposure of novel compounds, both in terms of pharmacology and toxicology.

In 2010, a detailed lung model was included in the commercial PBPK platform GastroPlus, allowing PBPK modelling to include the inhalation route of drug administration [17, 18]. In this study, we have detailed a fully mechanistic inhaled PBPK model of nemiralisib, building on a previously published simpler model [21], and proposed a novel way of parameterising the pulmonary absorption component of the model, including the use of lung systemic absorption rate constants derived from human physiological lung blood flows. In comparison, the simpler model using an earlier version of Simcyp treated the lung as one compartment and used a single lung absorption rate constant. In addition, the observed volume of distribution was used to fit tissue distribution rather than using a bottom-up approach based on in vitro input parameters. Moreover, the swallowed portion was characterised by a first-order model compared with an ACAT model predicting regional oral absorption.

Publications are beginning to emerge on the prediction of plasma profiles following inhalation administration using GastroPlus [28]. However, they are not always fully mechanistic and may not cover all specific inputs. For example, Salar-Behzadi et al. [28] used GastroPlus to highlight the value of realistic deposition data combined with experimental data for peripheral permeability, but did not discuss lung systemic absorption rate constants. In addition, a compartmental PK model for systemic distribution was applied when modelling inhaled budesonide.

Data after intravenous, oral and inhalation administration are highly desirable to allow correct characterisation of pulmonary drug absorption [17]. Data from an ADME study (GSK study number 206764; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03315559) [19] allowed such a characterisation for inhaled nemiralisib.

Initial models to describe the systemic distribution following intravenous administration were built using a perfusion-limited tissue model for nemiralisib, but the plasma Cmax was underpredicted for most subjects. A permeability-limited tissue model introduced a slight delay in the tissue distribution, while maintaining significant tissue distribution but enabling a more accurate prediction of the plasma Cmax. Small fluctuations in nemiralisib plasma concentrations (secondary peaking) were observed following intravenous dosing, as well as oral and inhalation dosing, and were likely caused by enterohepatic recirculation of nemiralisib [19]. However, enterohepatic recirculation was not incorporated into the PBPK model and could be considered a limitation of our approach.

The volume of distribution of nemiralisib at steady state following intravenous dosing of approximately 10 L/kg exceeds total body water, which is suggestive of extensive distribution beyond the plasma compartment [19]. A systemic PBPK model consists of multiple tissues, but only a few of the larger tissues drive the prediction of the plasma concentration profile. Therefore, only the Kp values of the larger tissues need to be predicted accurately to account for systemic distribution. In addition, it is possible to get an accurate prediction of the plasma profile based on combinations of inaccurate predictions of tissue distribution in individual tissues. To test our prediction accuracy, a preclinical rat tissue distribution study was conducted to determine total concentration in tissues driving systemic distribution, thus providing confidence in the clinical predictions. Although it is acknowledged that unbound drug defines pharmacology and toxicology [29], the focus of this manuscript was to predict differences in total drug concentrations in tissues using measured Rtp values to verify the PBPK model.

The clinical permeability-limited tissue model highlighted that liver, muscle and adipose are important tissues in terms of the distribution of nemiralisib in human, with the liver, due to its high Kp value (34.6), and muscle and adipose as the main components of body composition (around 33% each). In the rat, liver, muscle and skin are the most important tissues in terms of distribution of nemiralisib due to a predicted high liver Kp value and the significant contribution of muscle and skin to body composition of around 49% and 16%, respectively. Therefore, the liver, muscle and skin Rtp values were measured in rat, along with kidney, spleen and lung, each of interest for pharmacological reasons.

The predicted Rtp values for liver, kidney, spleen, muscle, lung and skin were close to or within a factor of three of the values measured in the rat tissue distribution study. This includes tissues such as liver and kidney, where active transport processes not specifically accounted for in the predictions are likely to have an impact. It should be noted that nemiralisib is not a substrate of liver uptake transporters. Retrospective ‘fitting’ of the rat SpecPStc value enabled all Rtp predictions to be within a factor of three of the measured values, and the fact that this fitted SpecPStc value is close to the human value provided a level of confidence in the human Rtp predictions, which cannot be verified with measured tissue data.

It is well known that a large proportion of an inhalation dose is often swallowed and therefore modelling the oral component is critical for compounds such as nemiralisib with significant oral absorption, resulting in 35% oral bioavailability. Plasma profiles indicated that a protracted absorption phase [19] and low PBPK input values of effective permeability were required to match the tmax of 6 h. For an adequate oral model, the absorption in the caecum and ascending colon needed to be reduced. This can be achieved by reducing the percentage of fluid in the colon to 0.01%, but this value is non-physiological and well below the lower limit of the range suggested in the literature [30]. Therefore, a more empirical adjustment of simply setting the ASF coefficient C3 to zero to switch off the absorption in the large intestine was adopted.

Nemiralisib has displayed high permeability, reasonable solubility and high rat lung tissue binding. It is this binding, combined with the basicity of the compound, that is thought to drive lung retention in the rat [31]. The clinical model, as parametrised by inputs from Table 1, demonstrates lung retention in the thoracic and bronchiolar compartments out to 20 h. The compound is predicted to rapidly dissolve in the lung and then permeate into the lung tissue, reaching a Cmax around 1 h. From 1 to 20 h, ‘steady state’ absorption from the thoracic and bronchiolar compartments is achieved as dissolved and tissue amounts decline in parallel (Fig. 6). As can be seen from Fig. 7, significant amounts of nemiralisib are predicted, by PBPK modelling, to distribute into tissues following inhalation administration, and therefore have the potential to act in the tissue. This is of particular importance for those diseases where PI3Kδ is designed to modulate immune responses within the tissues. To our knowledge, applications of PBPK for the prediction of concentrations at the site of action are rare and this study provides a contribution in this area [20].

Systemic absorption rate constants from the individual lung compartments are a key parameter in mechanistic inhaled modelling, but are difficult to determine as in vitro experiments to generate suitable values are not readily available. Moreover, empirical deconvolution from in vivo PK data is challenging due to multiple complex processes and the associated unknowns. Systemic absorption rate constants are generally considered to be permeability rate-limited and therefore compound-specific. However, in this study we took a novel approach, assuming blood flows to be rate-limiting for the highly permeable nemiralisib. We derived separate lung blood flow values for the two distinct pulmonary blood supplies so that the highly capilliarised alveolar region supplied by the pulmonary circulation had a faster rate than the regions supplied by the bronchial circulation. These values seem adequate for nemiralisib, but compounds where dissolution and permeability are rate-limiting may be less dependent on systemic absorption rate constants.

The plasma concentration versus time profiles of nemiralisib in human can be adequately predicted following inhalation dosing using mechanistic modelling, but matching the plasma concentrations does not validate predictions of the processes occurring within the lung prior to pulmonary absorption. Therefore, we used an inhaled clinical study where BAL samples were taken in addition to sampling of plasma. Deposition is dependent on the patient and the device, but we assumed the same deposition for the ADME study [19] and the inhalation study [3]. The predicted plasma concentration of 2.3 ng/mL at 24 h (trough) after the final dose (day 14) is comparable with the observed value of 1.72 ng/mL. The predicted dissolved mucus concentrations in the thoracic and bronchiolar compartments of 43 and 25 ng/mL, respectively, are in line with the measured lung epithelial lining fluid (ELF) concentration of 55.3 ng/mL. Based on the measured peak and trough plasma concentrations, steady state was reached by day 7, which is in keeping with the PBPK simulations, although the observed accumulation of approximately 4.5-fold on trough concentrations and 3-fold on peak values was slightly under predicted at 2.8-fold and 1.2-fold, respectively. In addition, the measured peak-to-trough ratios of approximately 3.2 on day 1 and 2.2 on day 14 were overpredicted at 12.1 on day 1 and 5.4 on day 14.

Conclusion

We built a fully mechanistic PBPK model that adequately simulated the systemic exposure of nemiralisib following inhalation administration. This gives weight to the use of systemic absorption rate constants from the lung based on lung blood flows, in vitro permeability from MDCK-MDR1 cells used directly as an input for lung permeability, and fraction unbound in plasma as a surrogate for lung binding when parameterising the pulmonary component of the PBPK model. Predicted concentrations at the site of administration were verified against clinical BAL data, and the prediction of tissue concentrations was verified using data obtained in the rat following intravenous infusion administration to steady state. Fully mechanistic inhaled PBPK models, such as the one described in this study, could have an impact for cross-molecule assessments in terms of lung retention and systemic exposure, in the context of both pharmacology and toxicology.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the PBPK advice provided by Viera Lukacova (Simulations Plus), and Victor R. Aguilar (Simulations Plus) for his assistance with the artwork.

Declarations

No funding was received for the preparation of this article. GlaxoSmithKline paid the open access fee.

Chris D. Edwards, Augustin Amour, Ed Taylor, Olivia Robb, Brett O’Brien, Aarti Patel and Andrew W. Harrell are employees of GlaxoSmithKline R&D and may hold stock or stock options. Neil A. Miller, Rebecca H. Graves & Edith M. Hessel were employees of GlaxoSmithKline R&D at the time this work was completed and may hold stock. Neil A. Miller and Rebecca H. Graves are now employees of Simulations Plus (UK) and may hold stock options and Edith M. Hessel is Chief Scientific Officer at Eligo Bioscience (Paris, France).

The clinical studies adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki, were funded by GSK and were approved by the London Harrow Research Ethics Committee. All subjects gave their written informed consent prior to any study procedure. All animal studies were ethically reviewed and were carried out in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and the GSK Policy on the Care, Welfare and Treatment of Animals.

All subjects provided their informed consent for the present research as stated above.

All authors provided their informed consent for publication.

Data sharing was not applicable to this article as no clinical datasets were generated specifically for this manuscript. Input data are provided in the manuscript.

The commercial PBPK platform GastroPlus® was used, as described in this manuscript.

Writing, review and editing of the manuscript: NAM, RHG. Review and editing of the manuscript: CDE, AA, ET, OR, BO’B, AP, AWH, EMH. Modelling and simulation: NAM, RHG, ET. Research designed: EMH, CDE, OR, BO’B. Preclinical PK studies: OR, BO’B.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-021-01066-2

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s40262-021-01066-2.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/115507225

Article citations

Insights into Inhalation Drug Disposition: The Roles of Pulmonary Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes and Transporters.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(9):4671, 25 Apr 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38731891 | PMCID: PMC11083391

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The In Vitro, In Vivo, and PBPK Evaluation of a Novel Lung-Targeted Cardiac-Safe Hydroxychloroquine Inhalation Aerogel.

AAPS PharmSciTech, 24(6):172, 11 Aug 2023

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 37566183

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling Approaches for Patients With SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Case Study With Imatinib.

J Clin Pharmacol, 62(10):1285-1296, 08 May 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 35460539 | PMCID: PMC9088354

Predicting Regional Respiratory Tissue and Systemic Concentrations of Orally Inhaled Drugs through a Novel PBPK Model.

Drug Metab Dispos, 50(5):519-528, 04 Mar 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35246463 | PMCID: PMC9073946

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

Clinical Trials (2)

- (3 citations) ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT03315559

- (1 citation) ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT01762878

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Drug Interactions for Low-Dose Inhaled Nemiralisib: A Case Study Integrating Modeling, In Vitro, and Clinical Investigations.

Drug Metab Dispos, 48(4):307-316, 02 Feb 2020

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 32009006

An Innovative Approach to Characterize Clinical ADME and Pharmacokinetics of the Inhaled Drug Nemiralisib Using an Intravenous Microtracer Combined with an Inhaled Dose and an Oral Radiolabel Dose in Healthy Male Subjects.

Drug Metab Dispos, 47(12):1457-1468, 24 Oct 2019

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 31649125

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling Accurately Predicts the Better Bronchodilatory Effect of Inhaled Versus Oral Salbutamol Dosage Forms.

J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv, 32(1):1-12, 07 Jun 2018

Cited by: 11 articles | PMID: 29878860

Advances in experimental and mechanistic computational models to understand pulmonary exposure to inhaled drugs.

Eur J Pharm Sci, 113:41-52, 25 Oct 2017

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 29079338

Review

1

1