Abstract

Free full text

Timing of elective surgery and risk assessment after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: an update

Associated Data

Summary

The impact of vaccination and new SARS‐CoV‐2 variants on peri‐operative outcomes is unclear. We aimed to update previously published consensus recommendations on timing of elective surgery after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection to assist policymakers, administrative staff, clinicians and patients. The guidance remains that patients should avoid elective surgery within 7 weeks of infection, unless the benefits of doing so exceed the risk of waiting. We recommend individualised multidisciplinary risk assessment for patients requiring elective surgery within 7

weeks of infection, unless the benefits of doing so exceed the risk of waiting. We recommend individualised multidisciplinary risk assessment for patients requiring elective surgery within 7 weeks of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. This should include baseline mortality risk calculation and assessment of risk modifiers (patient factors; SARS‐CoV‐2 infection; surgical factors). Asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection with previous variants increased peri‐operative mortality risk three‐fold throughout the 6

weeks of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. This should include baseline mortality risk calculation and assessment of risk modifiers (patient factors; SARS‐CoV‐2 infection; surgical factors). Asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection with previous variants increased peri‐operative mortality risk three‐fold throughout the 6 weeks after infection, and assumptions that asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 infection does not add risk are currently unfounded. Patients with persistent symptoms and those with moderate‐to‐severe COVID‐19 may require a longer delay than 7

weeks after infection, and assumptions that asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 infection does not add risk are currently unfounded. Patients with persistent symptoms and those with moderate‐to‐severe COVID‐19 may require a longer delay than 7 weeks. Elective surgery should not take place within 10

weeks. Elective surgery should not take place within 10 days of diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, predominantly because the patient may be infectious, which is a risk to surgical pathways, staff and other patients. We now emphasise that timing of surgery should include the assessment of baseline and increased risk, optimising vaccination and functional status, and shared decision‐making. While these recommendations focus on the omicron variant and current evidence, the principles may also be of relevance to future variants. As further data emerge, these recommendations may be revised.

days of diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, predominantly because the patient may be infectious, which is a risk to surgical pathways, staff and other patients. We now emphasise that timing of surgery should include the assessment of baseline and increased risk, optimising vaccination and functional status, and shared decision‐making. While these recommendations focus on the omicron variant and current evidence, the principles may also be of relevance to future variants. As further data emerge, these recommendations may be revised.

1. Recommendations

- 1

There is currently no evidence on peri‐operative outcomes after SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination and the omicron variant. Therefore, previous recommendations that, where possible, patients should avoid elective surgery within 7

weeks of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection remain, unless the benefits of doing so exceed the risk of waiting. We recommend individualised risk assessment for patients with elective surgery planned within 7

weeks of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection remain, unless the benefits of doing so exceed the risk of waiting. We recommend individualised risk assessment for patients with elective surgery planned within 7 weeks of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

weeks of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. - 2

Surgical patients should have received pre‐operative COVID‐19 vaccination, with three doses wherever possible, with the last dose at least 2

weeks before surgery. Confirming and optimising vaccination status should be actioned as soon as possible, either before primary care referral or at surgical decision‐making.

weeks before surgery. Confirming and optimising vaccination status should be actioned as soon as possible, either before primary care referral or at surgical decision‐making. - 3

Current measures designed to reduce the risk of patients acquiring SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in the peri‐operative period should continue and, in view of the increased transmissibility of omicron, should be augmented (e.g. respiratory protective equipment) where evidence supports this.

- 4

Patients should be requested to notify the surgical team if they test positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection within 7

weeks of their planned operation date. From there, a conversation should take place between the peri‐operative team and the patient about the risks and benefits of deferring surgery.

weeks of their planned operation date. From there, a conversation should take place between the peri‐operative team and the patient about the risks and benefits of deferring surgery. - 5

Elective surgery should not take place within 10

days of diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, predominantly because the patient may be infectious, which is a risk to surgical pathways, staff and other patients.

days of diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, predominantly because the patient may be infectious, which is a risk to surgical pathways, staff and other patients. - 6

Asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection with previous variants increased mortality risk three‐fold throughout the 6

weeks after infection. Given the lack of evidence with peri‐operative omicron infection, assumptions that asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic infection does not add risk are currently unfounded.

weeks after infection. Given the lack of evidence with peri‐operative omicron infection, assumptions that asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic infection does not add risk are currently unfounded. - 7

If elective surgery is considered within 7

weeks of diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, we recommend multidisciplinary discussions with the patient occur with documentation of the risks and benefits.

weeks of diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, we recommend multidisciplinary discussions with the patient occur with documentation of the risks and benefits.

- a

All patients should have their risk of mortality (and complications, where possible) calculated using a validated risk score.

- b

Risk modifiers based on patient factors (age; comorbid status); SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (timing; severity of initial infection; ongoing symptoms); and surgical factors (clinical priority; risk of disease progression; complexity of surgery) can then be applied to help estimate how underlying risk would be altered by undertaking surgery within 7

weeks of infection.

weeks of infection. - c

Patients should be advised that a decision to proceed with surgery within 7

weeks will be pragmatic rather than evidence‐based.

weeks will be pragmatic rather than evidence‐based.

- 8

Patients with persistent symptoms and those with moderate‐to‐severe COVID‐19 (e.g. those who were hospitalised) remain likely to be at greater risk of morbidity and mortality, even after 7

weeks. Therefore, delaying surgery beyond this point should be considered, balancing this risk against any risks associated with such delay.

weeks. Therefore, delaying surgery beyond this point should be considered, balancing this risk against any risks associated with such delay. - 9

In patients with recent or peri‐operative SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, avoidance of general anaesthesia in favour of local or regional anaesthetic techniques should be considered.

- 10

Rather than emphasising timing alone, we emphasise timing, assessment of baseline and increased risk, and shared decision‐making.

- 11

All patients awaiting surgery should address modifiable risk‐factors, such as through pre‐operative exercise, nutritional optimisation and stopping smoking.

2. Introduction

Pre‐operative SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was previously shown to be associated with significantly increased risks of morbidity and mortality. Data in the early phases of the pandemic demonstrated that peri‐operative SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was associated with clinically important increases in mortality, in some cases more than a 10‐fold increase [1, 2]. Furthermore, when surgery was undertaken within 6 weeks of infection, postoperative morbidity and mortality were also increased [3]. Notably, increased peri‐operative risk remained consistently elevated until 7

weeks of infection, postoperative morbidity and mortality were also increased [3]. Notably, increased peri‐operative risk remained consistently elevated until 7 weeks after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, at which point it returned to baseline. Therefore, recommendations were made to delay elective surgery for 7

weeks after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, at which point it returned to baseline. Therefore, recommendations were made to delay elective surgery for 7 weeks after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, unless the risks of deferring surgery outweighed the risk of postoperative morbidity or mortality associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection [4, 5].

weeks after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, unless the risks of deferring surgery outweighed the risk of postoperative morbidity or mortality associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection [4, 5].

As the COVID‐19 pandemic has progressed, disease therapy and prevention have developed, including vaccination [6]. Variants have emerged that differ in terms of their transmissibility, the severity of illness they cause and their ability to infect vaccinated patients. The omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 variant in particular has increased transmissibility and the potential to evade immunity acquired through previous SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, vaccination or both [7]. This variant also leads to less severe clinical illness than previous variants [7, 8, Wang et al., preprint, https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.30.21268495] and this is particularly so for patients who are vaccinated, which, in some countries is the majority of surgical patients. Compounding these concerns, disruption to the delivery of surgical care during the pandemic has significantly increased the number of patients awaiting surgery globally [9, 10]. In the face of these uncertainties, and the expectation of the imminent return to augmented surgical activity, clinical decision‐making regarding timing of surgery has become challenging.

We therefore aim to provide an update to the previously published consensus statement on SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, COVID‐19 and timing of elective surgery in adults to assist policymakers, administrative staff, clinicians and patients. This document focuses on the omicron variant, which is now strongly dominant in many countries. However, the principles may also be of relevance to future variants.

Prevention of peri‐operative SARS‐CoV‐2 infection

There is no robust evidence demonstrating whether the risks of morbidity and mortality after pre‐operative or peri‐operative infection with the omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 variant are lower than with earlier variants. Evidence informing this question is expected [11] but, meanwhile, it remains important to minimise the risk of patients either arriving at hospital incubating SARS‐CoV‐2 or acquiring it in hospital. Both are significant challenges with the omicron variant due to high transmissibility and high community, nosocomial and healthcare staff infection rates [7]. With millions of patients on waiting lists, actions that reduce the risk of service disruption by protecting the healthcare workforce and service are important in addition to individual patient outcomes.

Vaccination is the most effective intervention to reduce the severity of infection and thus peri‐operative complications, and should be strongly encouraged pre‐operatively. Vaccination with two doses has only a modest impact on the risk of infection with the omicron variant but has a moderate impact on reducing the severity of COVID‐19 [7], while a third vaccination dose significantly reduces the risk of infection and severity of illness [Andrews et al., preprint, https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.14.21267615]. Vaccination is likely to have clinical efficacy within 2 weeks [12] and therefore patients who are partially vaccinated are likely to benefit from a further dose or doses in the pre‐operative period, ideally arranged in primary care at the point of referral for consideration of surgery. If not done by the time patients have presented for surgical assessment, then vaccination should be strongly encouraged by surgical teams at this time. Modelling estimates that the impact of vaccination against COVID‐19 on reducing mortality was more marked in patients undergoing surgery than that of the general population [6]. This emphasises the importance of pre‐operative patient vaccination.

weeks [12] and therefore patients who are partially vaccinated are likely to benefit from a further dose or doses in the pre‐operative period, ideally arranged in primary care at the point of referral for consideration of surgery. If not done by the time patients have presented for surgical assessment, then vaccination should be strongly encouraged by surgical teams at this time. Modelling estimates that the impact of vaccination against COVID‐19 on reducing mortality was more marked in patients undergoing surgery than that of the general population [6]. This emphasises the importance of pre‐operative patient vaccination.

Prevention of staff–patient disease transmission in hospitals is also important to reduce risk. Mandatory vaccination of healthcare staff is currently under review as a condition of retaining or gaining such employment in the UK [13]. Irrespective of national policy, staff caring for patients having surgery, and particularly those who are high risk, should be vaccinated against COVID‐19, wherever possible [13].

Patients should be informed that, should they become SARS‐CoV‐2 positive before surgery, a risk assessment and possible deferment of surgery will be triggered (see online Supporting Information Appendix S1). Further actions to reduce the risk of peri‐operative patient infection with SARS‐CoV‐2 include:

Appendix S1). Further actions to reduce the risk of peri‐operative patient infection with SARS‐CoV‐2 include:

- • Adherence by patients awaiting surgery to practices that reduce the risk of community‐acquired SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, such as mask‐wearing, social distancing, hand hygiene, appropriate pre‐operative self‐isolation and adherence to shielding advice, where indicated;

- • Screening of hospital staff to prevent contact with infectious staff [14];

- • Maintaining dedicated pathways that separate patients who have been screened and tested negative for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection from contact with patients with suspected or confirmed infection and the staff and locations involved in their treatment [15];

- • Adherence by staff to practices that reduce the risk of in‐hospital SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission, such as the use of appropriate respiratory protective equipment, social distancing, hand hygiene and adherence to self‐isolation rules, where indicated;

- • Institutional implementation of environmental ventilation, air filtering, decontamination and provision of appropriate respiratory protective equipment consistent with best practice;

- • Minimising time spent by patients within healthcare environments;

- • Maintaining SARS‐CoV‐2 risk‐reducing measures once discharged from hospital to avoid potential infection during the early postoperative recovery phase, which could negatively affect patient outcomes.

Timing of elective surgery after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection

A combination of widespread testing and high community infection rates means that it is likely that many surgical patients will present with pre‐operative or peri‐operative SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. They might be asymptomatic, mildly symptomatic or pre‐symptomatic. Contact tracing data indicate high rates of symptomatic infection, with 89.8% for omicron compared with 85.5% of delta cases [7]. However, the severity of COVID‐19 following omicron infection appears to be milder than with previous variants [8, Wang et al., preprint, https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.30.21268495]. Rates of hospitalisation, hospital length of stay and case fatality rate are all reportedly lower [7, 8, 16, 17]. This logically leads to the hypothesis that the absolute risk of harm (morbidity or mortality) of undergoing surgery following recent SARS‐CoV‐2 infection could be lower than with previous variants. However, this hypothesis is untested with no data so far to confirm or refute it.

[7]. However, the severity of COVID‐19 following omicron infection appears to be milder than with previous variants [8, Wang et al., preprint, https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.30.21268495]. Rates of hospitalisation, hospital length of stay and case fatality rate are all reportedly lower [7, 8, 16, 17]. This logically leads to the hypothesis that the absolute risk of harm (morbidity or mortality) of undergoing surgery following recent SARS‐CoV‐2 infection could be lower than with previous variants. However, this hypothesis is untested with no data so far to confirm or refute it.

While there may be a temptation to ignore omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 infection with no or mild symptoms as a pre‐operative risk‐factor, it is notable that with previous variants, asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection increased mortality risk around three‐fold throughout the 6 weeks after infection. No data on omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 infection are available, and therefore assumptions that asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic infection does not add risk are currently unfounded.

weeks after infection. No data on omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 infection are available, and therefore assumptions that asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic infection does not add risk are currently unfounded.

Given the uncertainty of the impact of novel variables (variants, symptoms and vaccination) on peri‐operative outcomes, the default position should be to avoid elective surgery within 7 weeks of a diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, even in asymptomatic patients. However, we emphasise that this should be balanced against the consequences of this delay. If this is outweighed by the clinical risk of deferring surgery, such delay would be inappropriate. Baseline risk should be calculated using a validated risk assessment tool, such as the Surgical Outcome Risk Tool v2 (SORT‐2) [18]. How this risk could be altered by surgery within 7

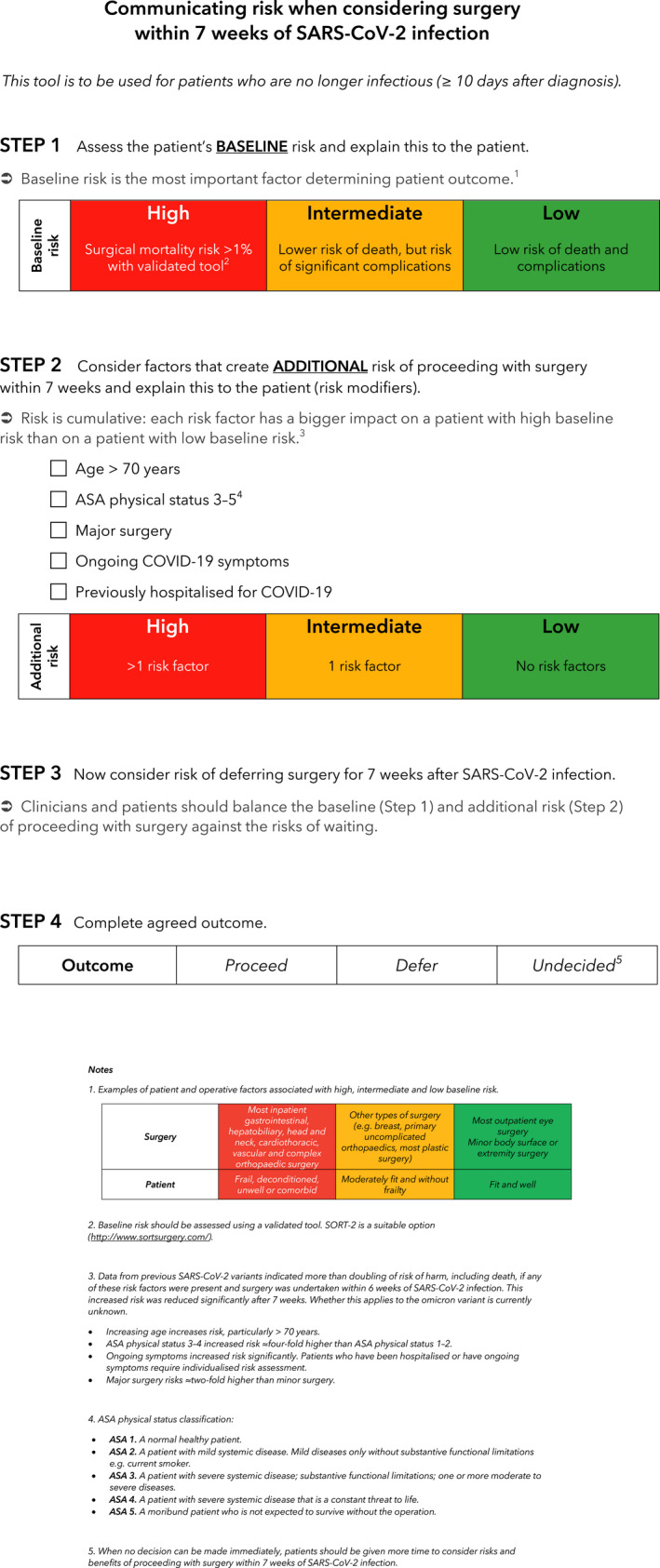

weeks of a diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, even in asymptomatic patients. However, we emphasise that this should be balanced against the consequences of this delay. If this is outweighed by the clinical risk of deferring surgery, such delay would be inappropriate. Baseline risk should be calculated using a validated risk assessment tool, such as the Surgical Outcome Risk Tool v2 (SORT‐2) [18]. How this risk could be altered by surgery within 7 weeks of diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection may be estimated by consideration of risk modifiers, including: patient factors (age; comorbid and functional status); SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (timing; variant; severity of initial infection; ongoing symptoms); and surgical factors (clinical priority; risk of disease progression; complexity of surgery) (Fig.

weeks of diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection may be estimated by consideration of risk modifiers, including: patient factors (age; comorbid and functional status); SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (timing; variant; severity of initial infection; ongoing symptoms); and surgical factors (clinical priority; risk of disease progression; complexity of surgery) (Fig. 1, Box

1, Box 1). Understanding these risks should inform shared decision‐making between the multidisciplinary team and the patient. Documentation should record the risks and benefits of timing of surgery and the process of decision‐making. Ideally, patients should be advised that a decision to proceed with surgery within 7

1). Understanding these risks should inform shared decision‐making between the multidisciplinary team and the patient. Documentation should record the risks and benefits of timing of surgery and the process of decision‐making. Ideally, patients should be advised that a decision to proceed with surgery within 7 weeks will not be evidence‐based, but pragmatic.

weeks will not be evidence‐based, but pragmatic.

Communicating risk when considering surgery within 7 weeks of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. This is a tool that may be used for patients who are no longer infectious (≥ 10

weeks of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. This is a tool that may be used for patients who are no longer infectious (≥ 10 days after diagnosis). Clinicians should begin by assessing baseline risk, then consider risk modifiers, followed by determining the risk of deferring surgery for 7

days after diagnosis). Clinicians should begin by assessing baseline risk, then consider risk modifiers, followed by determining the risk of deferring surgery for 7 weeks after infection. This communication tool should be used in conjunction with our recommendations to support shared decision‐making.

weeks after infection. This communication tool should be used in conjunction with our recommendations to support shared decision‐making.

The increased risk associated with surgery after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection does not fall until 7 weeks, thus there is no benefit in partial delay (e.g. the increased risk at 6

weeks, thus there is no benefit in partial delay (e.g. the increased risk at 6 weeks is similar to that at 3

weeks is similar to that at 3 weeks). Therefore, decision‐making should be dichotomised: defer for 7

weeks). Therefore, decision‐making should be dichotomised: defer for 7 weeks or do not defer.

weeks or do not defer.

Patients with persistent symptoms and those with moderate‐to‐severe COVID‐19 (e.g. those who were hospitalised) remain likely to be at greater risk of morbidity and mortality, even after 7 weeks [3]. Therefore, delaying surgery beyond this point should be considered, balancing this risk against any risks associated with such delay. Specialist assessment and individualised, multidisciplinary peri‐operative management are advised.

weeks [3]. Therefore, delaying surgery beyond this point should be considered, balancing this risk against any risks associated with such delay. Specialist assessment and individualised, multidisciplinary peri‐operative management are advised.

Elective surgery should be avoided during the period that a patient may be infectious (10 days). This includes patients who test positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 during pre‐operative screening (incidental SARS‐CoV‐2). Patients who are infectious pose a risk to healthcare workers, other patients and safe pathways of care. Furthermore, incidental SARS‐CoV‐2 may be pre‐symptomatic and may be associated with increased risk of postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients having elective surgery. When emergency surgery is required during this period, full transmission‐based precautions should be undertaken.

days). This includes patients who test positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 during pre‐operative screening (incidental SARS‐CoV‐2). Patients who are infectious pose a risk to healthcare workers, other patients and safe pathways of care. Furthermore, incidental SARS‐CoV‐2 may be pre‐symptomatic and may be associated with increased risk of postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients having elective surgery. When emergency surgery is required during this period, full transmission‐based precautions should be undertaken.

Risk assessments should take place at the time of scheduling surgery. Patients should also be informed that a positive pre‐operative SARS‐CoV‐2 test may trigger a review of risks of proceeding with surgery. This can be supported with a risk communication tool (Fig. 1).

1).

Isolation

It has been reported that pre‐operative isolation for longer than 3 days may be associated with an increased risk of postoperative pulmonary complications [19]. Although there is uncertainty in the interpretation of these results, prolonged pre‐operative isolation should be avoided unless clearly indicated. Patients should be advised to increase physical activity where feasible and adhere to prehabilitation principles during isolation and throughout the pre‐operative period. This includes pre‐operative exercise, nutritional optimisation and smoking cessation [20].

days may be associated with an increased risk of postoperative pulmonary complications [19]. Although there is uncertainty in the interpretation of these results, prolonged pre‐operative isolation should be avoided unless clearly indicated. Patients should be advised to increase physical activity where feasible and adhere to prehabilitation principles during isolation and throughout the pre‐operative period. This includes pre‐operative exercise, nutritional optimisation and smoking cessation [20].

Anaesthetic technique

Early evidence suggested no difference in peri‐operative outcomes based on the mode of anaesthesia [21]. However, more recent evidence indicates that in patients with recent or peri‐operative SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, local or regional anaesthetic techniques may be associated with a moderate (e.g. point estimates varying between 50–150%) reduction in the risk of postoperative pulmonary complications and mortality when compared with general anaesthesia [19, 22]. It is possible that these data are prone to bias through unmeasured covariates and have yet to be reproduced in the setting of omicron and vaccination. On balance, in patients with recent or peri‐operative SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, avoidance of general anaesthesia in favour of local or regional anaesthetic techniques should be considered.

Discussion

The necessity to proceed with elective surgical recovery must be balanced with delivering surgery as safely as possible. Previous guidance was more robustly evidence‐based [4] and much still applies. However, there is currently a lack of data to specifically inform changes in peri‐operative risk. Although this information is expected, the anticipated high number of patients with pre‐operative SARS‐CoV‐2 omicron infection with or without previous vaccination has created uncertainty prompting pragmatic revision of our recommendations.

Decisions about proceeding with surgery after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection require a balanced risk assessment. While the default remains to avoid surgery within 7 weeks of infection or with ongoing symptoms, this should be balanced against the risk of delay, based on clinical priority and risk of disease progression. Where delay is indicated, this should be for the full 7

weeks of infection or with ongoing symptoms, this should be balanced against the risk of delay, based on clinical priority and risk of disease progression. Where delay is indicated, this should be for the full 7 weeks. If elective surgery is to take place within 7

weeks. If elective surgery is to take place within 7 weeks of infection or with ongoing symptoms, a multidisciplinary discussion should be undertaken that either includes the patient or is discussed with the patient as part of the process of informed consent. Risk assessment should account for patient factors, infection and peri‐operative considerations, and should be mindful of the impact of this on the absolute risk of harm to the patient. Rather than emphasising timing alone, we emphasise combining timing, assessment of risk and shared decision‐making.

weeks of infection or with ongoing symptoms, a multidisciplinary discussion should be undertaken that either includes the patient or is discussed with the patient as part of the process of informed consent. Risk assessment should account for patient factors, infection and peri‐operative considerations, and should be mindful of the impact of this on the absolute risk of harm to the patient. Rather than emphasising timing alone, we emphasise combining timing, assessment of risk and shared decision‐making.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Patient information about timing of elective surgery soon after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

Acknowledgements

KE is an Editor of Anaesthesia. SM is the National Clinical Director for critical and peri‐operative care, NHS England and NHS Improvement. No external funding or other competing interests declared.

Notes

[Correction added on 18 March 2022, after first online publication: On page 3, column 1, paragraph 3, the first sentence has been updated in this version.]

Contributor Information

K. El‐Boghdadly, Email: moc.liamg@yldadhgoble, @elboghdadly.

T. M. Cook, @doctimcook.

T. Goodacre, @teegoodacre.

J. Kua, @justin_kua.

S. McNally, @scarlettmcnally.

N. Mercer, @NigelMercer.

S. R. Moonesinghe, @rmoonesinghe.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15699

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/anae.15699

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/123526931

Article citations

Optimal surgical timing for lung cancer following SARS-CoV-2 infection: a prospective multicenter cohort study.

BMC Cancer, 24(1):1250, 09 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39385173 | PMCID: PMC11465869

Inhaled Nitric Oxide ReDuce postoperatIve pulmoNAry complicaTions in patiEnts with recent COVID-19 infection (INORDINATE): protocol for a randomised controlled trial.

BMJ Open, 14(3):e077572, 14 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38485487 | PMCID: PMC10941156

The Outcomes of Patients with Omicron Variant Infection who Undergo Elective Surgery: A Propensity-score-matched Case-control Study.

Int J Med Sci, 21(5):817-825, 17 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38616997 | PMCID: PMC11008485

Economic Impact of COVID-19 on a Free-Standing Pediatric Ambulatory Center.

J Clin Med Res, 16(2-3):56-62, 16 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38550553 | PMCID: PMC10970035

Association between anesthesia technique and death after hip fracture repair for patients with COVID-19.

Can J Anaesth, 71(3):367-377, 21 Dec 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38129357

Go to all (31) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19 and timing of elective surgery: A multidisciplinary consensus statement on behalf of the Association of Anaesthetists, the Centre for Peri-operative Care, the Federation of Surgical Specialty Associations, the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Anaesthesia, 76(7):940-946, 18 Mar 2021

Cited by: 74 articles | PMID: 33735942 | PMCID: PMC8250763

Timing of elective surgery and risk assessment after SARS-CoV-2 infection: 2023 update: A multidisciplinary consensus statement on behalf of the Association of Anaesthetists, Federation of Surgical Specialty Associations, Royal College of Anaesthetists and Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Anaesthesia, 78(9):1147-1152, 19 Jun 2023

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 37337416

Timing of surgery and elective perioperative management of patients with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection: a SIAARTI expert consensus statement.

J Anesth Analg Crit Care, 2(1):29, 22 Jun 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37386538 | PMCID: PMC9214464

Omicron, Long-COVID, and the Safety of Elective Surgery for Adults and Children: Joint Guidance from the Therapeutics and Guidelines Committee of the Surgical Infection Society and the Surgery Strategic Clinical Network, Alberta Health Services.

Surg Infect (Larchmt), 24(1):6-18, 29 Dec 2022

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 36580648

Review

1

,

2

1

,

2