Abstract

Background

Consistent use of reliable and clinically appropriate outcome measures is a priority for clinical trials, with clear definitions to allow comparability. We aimed to develop a core outcome set (COS) for pulmonary disease interventions in primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD).Methods

A multidisciplinary international PCD expert panel was set up. A list of outcomes was created based on published literature. Using a modified three-round e-Delphi technique, the panel was asked to decide on relevant end-points related to pulmonary disease interventions and how they should be reported. First, inclusion of an outcome in the COS was determined. Second, the minimum information that should be reported per outcome. The third round finalised statements. Consensus was defined as ≥80% agreement among experts.Results

During the first round, experts reached consensus on four out of 24 outcomes to be included in the COS. Five additional outcomes were discussed in subsequent rounds for their use in different subsettings. Consensus on standardised methods of reporting for the COS was reached. Spirometry, health-related quality-of-life scores, microbiology and exacerbations were included in the final COS.Conclusion

This expert consensus resulted in a COS for clinical trials on pulmonary health among people with PCD.Free full text

A BEAT-PCD consensus statement: a core outcome set for pulmonary disease interventions in primary ciliary dyskinesia

Associated Data

Abstract

Background

Consistent use of reliable and clinically appropriate outcome measures is a priority for clinical trials, with clear definitions to allow comparability. We aimed to develop a core outcome set (COS) for pulmonary disease interventions in primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD).

Methods

A multidisciplinary international PCD expert panel was set up. A list of outcomes was created based on published literature. Using a modified three-round e-Delphi technique, the panel was asked to decide on relevant end-points related to pulmonary disease interventions and how they should be reported. First, inclusion of an outcome in the COS was determined. Second, the minimum information that should be reported per outcome. The third round finalised statements. Consensus was defined as ≥80% agreement among experts.

Results

During the first round, experts reached consensus on four out of 24 outcomes to be included in the COS. Five additional outcomes were discussed in subsequent rounds for their use in different subsettings. Consensus on standardised methods of reporting for the COS was reached. Spirometry, health-related quality-of-life scores, microbiology and exacerbations were included in the final COS.

Conclusion

This expert consensus resulted in a COS for clinical trials on pulmonary health among people with PCD.

Tweetable abstract

A core outcome set for clinical trials on pulmonary health among people with primary ciliary dyskinesia has been constructed by expert consensus https://bit.ly/3RDABxr

Introduction

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare motile ciliopathy that is both clinically and genetically heterogeneous. Due to abnormal function of the respiratory cilia, recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections occur, resulting in bronchiectasis, atelectasis and decline in lung function [1–3]. Most mutations are inherited through autosomal recessive lineage, although autosomal dominant and X-chromosomal modes of inheritance have also been described [4]. Prevalence was previously estimated to be between 1:15 000 and 1:30

000 and 1:30 000, but more recent population genomic datasets have estimated it to be as high as one in 7500 live births [5].

000, but more recent population genomic datasets have estimated it to be as high as one in 7500 live births [5].

Current treatment methods are largely based on treatment strategies for cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis, focusing on symptom management [6–8]. There have only been two published, randomised controlled clinical trials of any treatment for PCD, and the only evidence-based treatment available so far in PCD is azithromycin maintenance therapy, which reduced exacerbation rate by 50% [9, 10]. A single-centre trial examining inhaled hypertonic saline failed to improve quality of life measured by the St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire compared to isotonic saline in 22 people with PCD, although subjects perceived improvement in their health. Unfortunately, this study was underpowered due to the larger than anticipated variability in outcome measures [11]. Additional clinical trials are needed to assess efficacy of current treatments and explore future treatment opportunities [9]. Therefore, a disease-specific Clinical Trial Network for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia has been established [12].

Selection of clinically appropriate and responsive end-points is of great importance for any clinical trial, but especially in rare diseases, where comparison and meta-analysis of trials are needed [13, 14]. Outcomes should be clearly defined, as clear definitions are needed to replicate and compare trials [15]. Therefore, several fields have created a pre-defined core outcome set (COS) to be used in specific situations. The Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative has defined a COS to be “an agreed standardised set of outcomes that should be measured and reported, as a minimum, in all clinical trials in specific areas of health or health care” [16]. Examples are a COS for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors, paediatric functional abdominal pain disorders and exacerbations of COPD [17–19].

Pulmonary disease has been a primary focus of treatment strategies for PCD, and to date, all clinical trials target pulmonary disease. A recent scoping review by Gahleitner et al. [20] identified 24 clinical outcome measures used in clinical studies assessing pulmonary disease in PCD, of which spirometry and chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) were most commonly reported. They found large variation in definitions, methods of collecting and reporting outcomes and sampling frequency. This review confirms that defining a COS for phase 2 and 3 clinical PCD trials is necessary to ensure reproducibility of studies and for use in future trials and prospective cohorts [20].

The aims of this consensus statement consist of reaching consensus on:

a COS to be implemented in all PCD pulmonary disease interventions;

standardising methods of collecting/measuring and reporting the outcomes that are included in the COS; and

additional outcomes not included in the COS that should be included in different settings or with specific interventions.

Methods

Participants

This study was developed in the framework of Better Experimental Approaches to Treat Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (BEAT-PCD), a clinical research collaboration (CRC) of researchers and clinicians, supported by the European Respiratory Society. The primary goal of the network is to improve diagnosis and treatment of people with PCD through the coordination of research from basic science to clinical care. As part of the project, a working group was established on the topic of clinical trials, of which one objective was to define reliable clinical outcome measures and biomarkers [21]. During an open BEAT-PCD online meeting, participants were invited to join the core group of the consensus project. Additional experts were invited due to their expertise in research on pulmonary outcome measures. The core group also contributed to the consensus, with the exclusion of one facilitator (R. Kos), who did not participate in the e-survey voting. After the establishment of the core group, they selected experts for this consensus statement based on their experience in PCD research, particularly on respiratory disease. The core group aimed to ensure that experts from different countries and continents were included, with expertise on both children and adults with PCD. This resulted in a list of 25 experts from 17 countries who were invited to form the expert panel. Since the consensus focuses on outcomes related to pulmonary disease interventions, the panel did not include any members with expertise in manifestations of PCD affecting other organs. Furthermore, as the focus was on experts in design and execution of studies, no patient representatives were included in the set-up of the COS. However, patient support groups are an integral part of the BEAT-PCD CRC and will be involved in later phases of this process.

Study design

During the first meeting, it was agreed that the aim of this group was to provide a consensus for a COS to be used in all pulmonary disease interventions in PCD. Additional objectives were to reach consensus of standardised methods of reporting and additional outcomes to be used in different subsettings.

We used a modified e-Delphi approach and set the cut-off for consensus at 80% agreement. A five-point Likert scale was used to assess agreement (“agree” and “strongly agree”); if an expert was “neutral” or disagreed (“disagree” or “strongly disagree”), they were required to provide a reason. Where relevant, questions with checkboxes were used, which allowed experts to select as many options as deemed relevant. Experts received a survey reminder 14 days after the initial invitation. Thereafter, a maximum of three reminders were sent. Before each survey round, the core group met to define the questions. After each round, data were analysed, both quantitatively and qualitatively, using appropriate descriptive statistics (mean±sd, median (interquartile range)). Anonymised results were presented to the core group in the first instance, and subsequently to the expert panel along with a survey invitation for the next round.

During the first round, the focus was on identifying outcomes that should be included in the COS. The outcome measure list consisted of 24 items taken from a systematic review from 2020 by Gahleitner et al. [20] and represented all relevant end-points that had been used in previous PCD clinical studies. The expert panel was asked if they agreed that these outcomes should be part of the core outcome set. An additional free-text question was included so that experts could suggest additional outcome measures that were not included in the list. In the second round, we focused on outcomes that did not reach consensus but had >40% agreement among experts, to investigate whether they might be useful in different settings or for specific interventions or specific age groups. Moreover, in this round we also investigated what the standardised method of reporting should be for the outcomes that were agreed to be included in the COS during the first round. Finally, in the third round, several statements were presented on the use of outcomes in different settings; the threshold for consensus remained at 80% agreement.

Results

Expert panel

Of the 25 invited experts, 24 (96%) accepted the invitation; characteristics of the expert panel are summarised in table 1. Within this expert panel 54% are female and experts were located across four continents (50% were located in Western Europe). Experts were evenly distributed between paediatric (38%) and adult (42%) pulmonology, with an additional 8% working on both. Other areas of expertise consisted of clinical epidemiology and general paediatrics. The mean±sd percentage of time spent on research was 41.4±26% and the length of experience was 19±8.0 years, corresponding to 457 accumulated years of experience within the expert panel. All experts responded to at least two survey rounds.

TABLE 1

Demographics of the expert panel

| Gender | |

Male Male | 9 (38) |

Female Female | 13 (54) |

Do not wish to disclose Do not wish to disclose | 2 (8) |

| Location | |

Australia Australia | 1 (4) |

Northern Europe Northern Europe | 4 (17) |

Western Europe Western Europe | 12 (50) |

Eastern Europe Eastern Europe | 1 (4) |

Southern Europe Southern Europe | 2 (8) |

Western Asia Western Asia | 1 (4) |

North America North America | 2 (8) |

South America South America | 1 (4) |

| Place of work | |

Academic medical centre Academic medical centre | 14 (58) |

Hospital Hospital | 4 (17) |

University University | 6 (25) |

| Field of expertise | |

Paediatric pulmonology Paediatric pulmonology | 9 (38) |

Adult pulmonology Adult pulmonology | 10 (42) |

Both Both | 2 (8) |

Other Other | 3 (13) |

| Research involvement | |

Lead investigator Lead investigator | 22 (92) |

Member of a research team Member of a research team | 18 (75) |

Involved with funding research Involved with funding research | 9 (38) |

| Experience years | 19.0±8.0 |

| Work hours dedicated to research % | 41.4±25.9 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean±sd.

Outcome parameter selection

The first round was open from the 22 February 2022 to 17 May 2022. All experts responded to the questionnaire and the results are summarised in table 2 and supplementary figure S1. From the 24 outcomes included in the questionnaire, consensus was reached on four parameters: spirometry (100%), health-related quality of life (HRQoL) scores (100%), exacerbations (96%) and microbiology (83%); these were included in the COS, as shown in table 3. 15 outcome parameters scored <40% agreement; therefore, they were no longer considered for the COS, as shown in table 2.

TABLE 2

Agreement between experts on clinical outcome measures to be included in the core outcome set from round one. All outcomes with >80% agreement were included; all outcomes with <40% agreement were dropped from further rounds.

| Agreement | |

| Spirometry# | 100 |

| HRQoL scores# | 100 |

| Exacerbations# | 96 |

| Microbiology# | 83 |

| Anthropometric measures | 71 |

| Chest HRCT/CT | 67 |

| Physical activity | 57 |

| Dyspnoea score | 50 |

| Cough | 42 |

| Lobectomy/lung resection¶ | 39 |

| Nutrition¶ | 35 |

| Multiple breath washout¶ | 33 |

| Inflammatory markers¶ | 30 |

| Exercise testing¶ | 26 |

| Fertility¶ | 26 |

| Body plethysmography¶ | 25 |

| Sputum properties¶ | 22 |

| Sleep¶ | 22 |

| Chest radiography¶ | 17 |

| Breath profile/breathomics¶ | 17 |

| Chest MRI¶ | 12 |

| Blood gas¶ | 9 |

| Vitamin D¶ | 9 |

| Metabolic profile¶ | 4 |

Data are presented as %. HRQoL: health-related quality of life; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging. #: outcomes with >80% agreement; ¶: outcomes with <40% agreement.

TABLE 3

Core outcome set for clinical trials evaluating all pulmonary disease interventions in primary ciliary dyskinesia

| Spirometry | FEV1 % predicted based on the reference values of the GLI |

| FEV1 z-scores based on the reference values of the GLI | |

| Health-related quality-of-life scores | Quality-of-Life instrument for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia |

| Exacerbations | BEAT-PCD consensus definition by Lucas et al. [22]# |

| Microbiology | Staphylococcus aureus Methicillin-resistant versus methicillin-sensitive Pseudomonas aeruginosa Haemophilus influenzae |

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; GLI: Global Lung Initiative; BEAT-PCD: Better Experimental Approaches to Treat Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. #: no consensus was reached, but this definition received the majority of votes.

Five outcome parameters scored between 40% and 80% agreement. Panellists commented that anthropometric measures (71% agreement) were easy, inexpensive and important for assessing growth and nutritional status, while associated with pulmonary disease severity. Nonetheless, they also stated that these measures were mostly relevant for growing children, and that they are unlikely to change in the course of a clinical trial. They concluded that anthropometric measures were unsuitable for a COS, as it would only be relevant for paediatric patients. Regarding chest HRCT/computed tomography (CT) (67% agreement), panellists commented that it is useful for identifying structural lung disease. However, they found that the use of chest HRCT/CT should be limited in paediatric patients due to concerns regarding cumulative dose of ionising radiation exposure; that it is resource heavy; and not yet sufficiently standardised due to lack of disease-specific scoring scales to be part of a COS. Panellists suggested that physical activity (57% agreement) is clinically important; however, this is already partially captured by the HRQoL scores and there is no established method for measuring this in people with PCD, which makes it unsuitable for a COS. As for the dyspnoea scores (50% agreement), panellists commented that although it is easy, simple and cheap to measure, it has not been validated and is mainly relevant in subsets of patients (elderly, or patients with severe lung disease). Finally, regarding cough (42% agreement) panellists mentioned it was a common patient complaint that is easily captured. Nonetheless, several experts thought that this symptom would be unlikely to decrease during a clinical trial; is very subjective; and lacks evidence and an established scoring system.

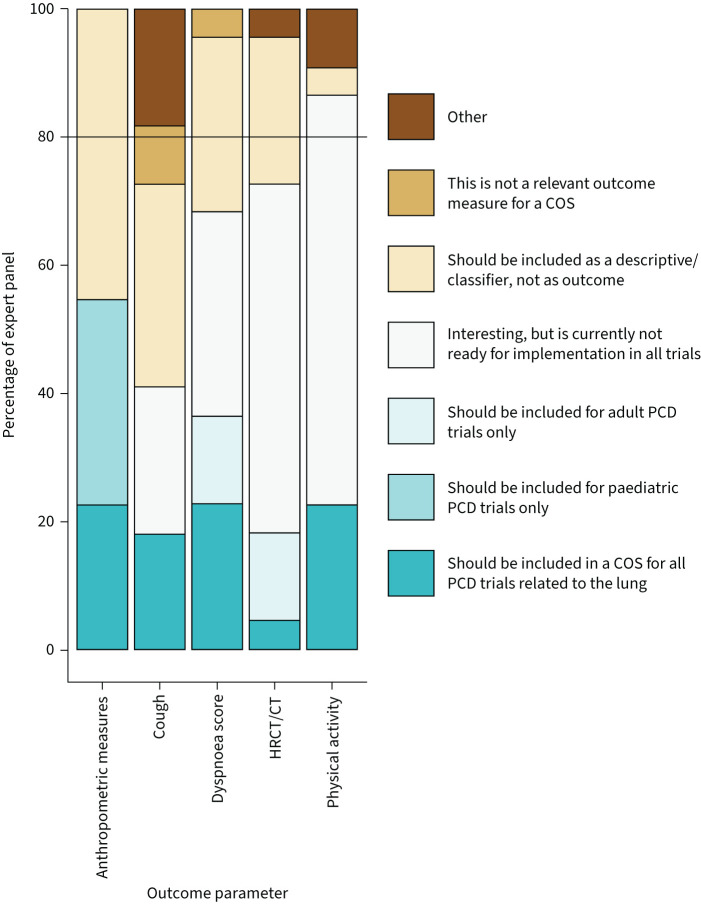

During the second round, open from 23 May 2022 to 15 July 2022, 22 (92%) out of 24 experts responded. The five outcome parameters that obtained between 40% and 80% agreement in round one were revisited; these results are summarised in figure 1. On anthropometric measures, 55% voted that it should be included in a COS for either all (23%) or paediatric-only (32%) PCD pulmonary disease interventions; the other 45% of experts voted that it should be included as a descriptive/classifier measurement rather than an outcome parameter. Experts did not reach consensus over cough: 18% agreed it should be in the COS, and 32% agreed it should be measured as a descriptive symptom. Regarding dyspnoea score, 4% of experts did not find this a relevant outcome measure. However, 96% agreed that these scores are of interest, of whom 37% agreed it should be in a COS for either all (23%) or adult-only (14%) trials; 27% agreed it should be measured as descriptive measurement; and another 32% felt that these scores are not yet ready for implementation in all trials. All experts thought that HRCT/CT is a parameter of interest: the majority (55%) found this parameter not ready for implementation in all trials; 19% agreed either it should be in a COS for all (5%) or adult-only (14%) trials; and 23% agreed it should be measured as a descriptive measurement. Most (87%) experts found physical activity a parameter of interest: 23% agreed it should be in a COS for all trials, but the majority (64%) found this parameter not ready for implementation in all trials.

Results for selection of most suitable outcome parameters by the expert panel during round two, revisiting outcomes that did not reach consensus in round one. To be considered a parameter of interest, agreement had to be >80% among experts (black line). All answer options except “not relevant” and “other” were counted towards agreement. COS: core outcome set; PCD: primary ciliary dyskinesia; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; CT: computed tomography.

The final round, open from 26 August 2022 to 21 October 2022, received responses from 21 (88%) out of 24 experts. Based on round two, statements on anthropometric measures, dyspnoea score, HRCT/CT and physical activity were presented. Consensus was reached on statements on all four outcome measures, as shown in table 4.

TABLE 4

Outcomes that are not included in the core outcome set, but are parameters of interest in different subsettings

| Anthropometric measures | Should be measured in all trials, but lacks consensus on if it should be measured as an outcome parameter or descriptive measurement |

| Is of higher relevance in paediatric compared to adult patients | |

| Physical activity | Is an outcome parameter of interest, but lacks consensus on being currently ready for implementation |

| Dyspnoea score | Is a measurement of interest, but lacks consensus on being currently ready for implementation, as an outcome parameter, or as a descriptive measurement |

| Is of higher relevance in adults compared to paediatric patients | |

| HRCT/CT | Is a measurement of interest, but lacks consensus on being currently ready for implementation, as an outcome parameter, or as a descriptive measurement |

HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; CT: computed tomography.

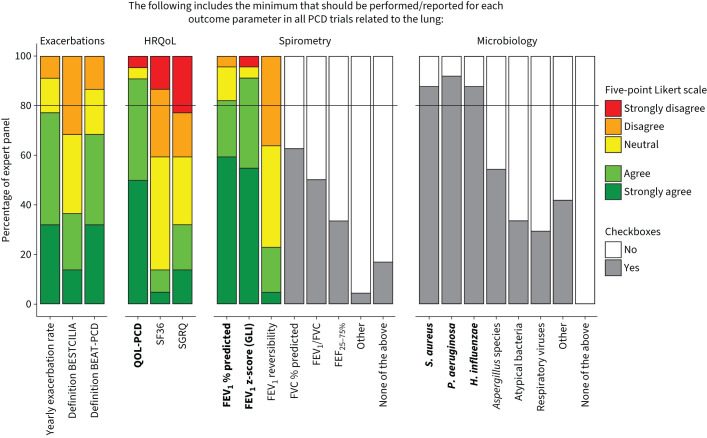

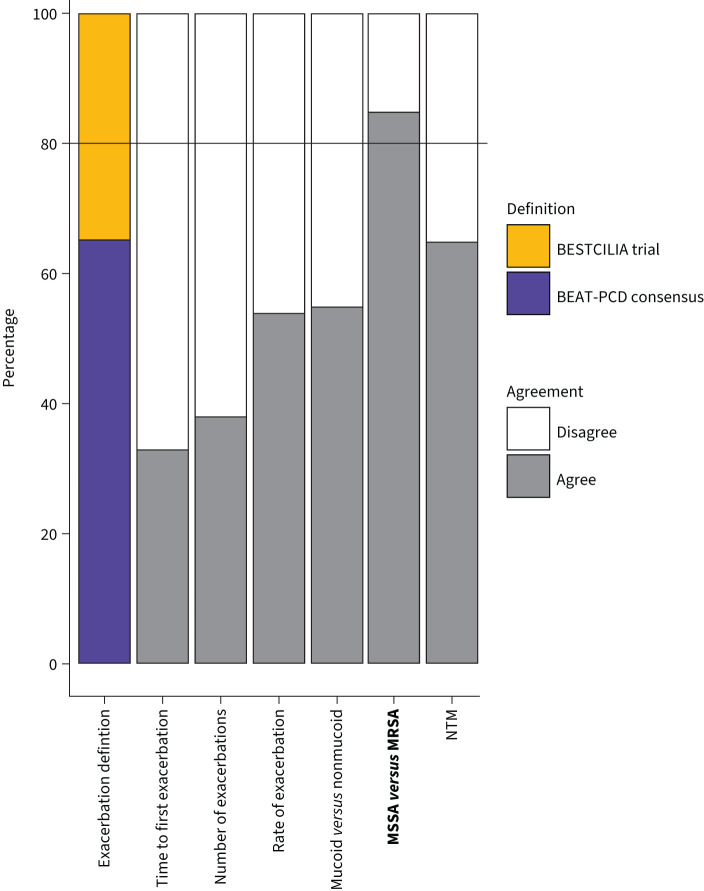

Standardised methods for reporting of COS

During round two, experts agreed on the minimum that should be performed and reported for each outcome parameter selected based on results from round one (figure 2). Consensus was reached on methods pertaining to HRQoL, spirometry, and microbiology, as shown in table 3. For HRQoL, the expert panel agreed on the use of the Quality-of-Life instrument for PCD (QOL-PCD), the first disease-specific validated HRQoL instrument for PCD [23, 24]. The panellists agreed that both FEV1 % pred and z-scores should be reported. They found that % predicted allows for easier clinical interpretation and z-scores provide a more accurate reference, especially in children. Panellists agreed that positive cultures of Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Haemophilus influenzae should be reported as part of the COS. In the third round (figure 3), the exacerbation definition of the BEAT-PCD consensus statement by Lucas et al. [22] attained a majority of votes (67%), over the BESTCILIA trial definition [10], but the votes did not reach the 80% consensus cut-off. Consensus was reached pertaining the method of reporting S. aureus cultures that the distinction should be made between methicillin-sensitive S. aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus.

Results for agreement on the minimum that should be performed/reported for all outcomes in the core outcome set, from round 2. Experts used a five-point Likert scale to report agreement and used multiple choice boxes to indicate parameters of interest. Consensus demanded an 80% agreement (black line), including both the answer options “agree” and “strongly agree” or a checked box; outcome parameters that reached consensus are indicated in bold. PCD: primary ciliary dyskinesia; HRQoL: health-related quality of life; BEAT-PCD: Better Experimental Approaches to Treat Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia; QOL-PCD: Quality of Life instrument for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia; SF36: 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SGRQ: St George's Respiratory Questionnaire; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; GLI: Global Lung Initiative; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEF25–75%: forced expiratory flow at 25–75% of FVC; S. aureus: Staphylococcus aureus; P. aeruginosa: Pseudomonas aeruginosa; H. influenzae: Haemophilus influenzae.

Results from round three, on choice of standardised method for reporting of outcomes. Experts were asked to choose between two exacerbation definitions, followed by the question whether they agreed or disagreed that these parameters should be included in the core outcome set. Outcome parameters that reached consensus are indicated in bold. BEAT-PCD: Better Experimental Approaches to Treat Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia; MSSA: methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; MRSA: methicillin-resistant S. aureus; NTM: nontuberculous mycobacteria.

Discussion

This study developed a COS for future clinical trials in PCD. Due to the rarity of PCD, only very few studies have been done in people with PCD. Treatment is mostly extrapolated from cystic fibrosis studies and studies in “non-cystic fibrosis” bronchiectasis, which may include small numbers of people with PCD [9]. With increased interest from both researchers and pharmaceutical companies in this disease and an increasing number of trials being planned, there is a clear need to standardise the use and reporting of outcome measures. This COS builds on a scoping review by Gahleitner et al. [20], which identified 24 potential outcome measures and emphasised the need for standardisation of measurement and reporting of outcome measurements. In this study, consensus was reached that spirometry, HRQoL scores, microbiology and exacerbations should be included in the final COS in PCD.

Although this COS was developed for use in respiratory disease interventions in PCD, we recommend that prospective observational studies, especially large collaborative ones, should follow the recommendations for standardised recording of relevant parameters such as % predicted and z-scores for FEV1. A standardised instrument to capture frequency and characteristics of clinical symptoms in people with PCD (FOLLOW-PCD questionnaire) has already been piloted in clinical setting [25]. It is important to note that FOLLOW-PCD does not capture the day-to-day symptom variability, and in general, measures relying on clinical features might not be sensitive enough to capture symptoms that the patients are accustomed to and tend to underreport. This instrument also includes modules for the reporting of spirometry and microbiology, but does not include the QOL-PCD and exacerbation definitions. The FOLLOW-PCD instrument and the COS can be considered complementary in the aim to standardise care and research for PCD, and to increase comparability of datasets and studies.

This COS excluded several outcome measures in different phases of the e-Delphi process. This does not mean that these end-points should not be used in clinical trials, but merely that, for various reasons, they should not be implemented in all trials on pulmonary disease interventions. There are also several newer techniques to measure end-points, such as multiple breath washout, and nonionising radiation exposure. However, new techniques are often not widely available and/or thoroughly validated, which makes them unsuitable for a COS. Like standards of care, standards for research such as a COS should be re-evaluated in the future to assess the development of novel outcomes.

Expert consensus was reached on how to report spirometry values, HRQoL scores and microbiology results. For exacerbations, there was a majority vote, but no consensus, for the use of the BEAT-PCD consensus definition over the BESTCILIA definition [10, 22]. It is important to note that neither exacerbation tool has been clinically validated. They are based on expert consensus, and have not been tested against physiological measures. For microbiology, experts agreed on reporting three pathogens; it is important to note that this is for research practice; for clinical practice, there is a consensus statement on infection prevention and control [26]. Finally, the aim of this consensus was not to provide standard operating procedures (SOPs), but on which values should minimally be reported. The development of SOPs can aid in the standardisation of both research and clinical practise.

A limitation of this study was the lack of patient involvement in the development of the final COS. As part of the BEAT-PCD CRC, patient support groups are being brought together in a communication network actively involved in research [27]. With advancement of this network, patient organisations will be involved in the future development and adaptation of core outcome sets. Another limitation of this study is that we did not provide definitions of the outcome measures, which may have led to some ambiguity of the interpretation among experts. For example, an increase in cough can be considered good for mucociliary clearance, but bad for quality of life. It was deliberately chosen not to provide a definition to minimise possible bias introduced by the phrasing of the question and definition provided on the experts’ perspectives on these outcomes.

This COS is designed for phase 2 and 3 trials for pulmonary disease interventions in PCD. Additional therapy-specific and trial-specific end-points are likely to be required, for example, for personalised medicine treatments like those of gene or transcript therapies [9]. These could include for example restoration of ciliary function or measurement of mucociliary clearance. Only small numbers of patients may be available for recruitment; therefore, compound outcomes and novel trial designs with fewer patients may be required.

In order to ensure incorporation of the COS in future clinical studies, dissemination of these results within the research community and companies is crucial. In this study, a large group of stakeholders from different continents has been involved, including Europe, North America, South America and Australia. In addition, some of the co-authors are part of PCD clinical trials network, linking these results to companies and organisations involved in PCD trials [12].

In summary, in the framework of the European Respiratory Society CRC BEAT-PCD, a core outcome set for respiratory disease interventions in PCD has been identified using a three-round modified Delphi survey. Anthropometric measures, chest HRCT/CT, physical activity and dyspnoea score, were deemed not yet ready. Thus, the COS includes spirometry, HRQoL, microbiology and exacerbations.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00115-2023.SUPPLEMENT

Footnotes

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Support statement: The BEAT-PCD clinical research collaboration is supported by the European Respiratory Society. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

Conflict of interest: S. Aliberti has received fees outside of this work from Insmed, Zambon, AstraZeneca, CSL Behring GmbH, Grifols, Fondazione Internazionale MENARINI, MSD Italia S.r.l., Brahms, Physioassist SAS and GlaxoSmithKline. S.D. Dell has received grants outside of this work from Boehringer Ingelheim, Vertex and Sanofi, and she owns the copyright to the PCD-QOL Questionnaires. T.W. Ferkol has received consulting fees from Translate Bio and Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals. R.A. Athanazio has received personal fees outside of this work from Astrazeneca, Chiesi, GSK, Omron, Sanofi, Vertex and Zambon. K.G. Nielsen is part of the European Reference Network on respiratory diseases (ERN-LUNG) and director of PCD CTN. F.C. Ringshauen has received fees outside of this work from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celtaxsys, Corbus, Insmed, Novartis, Parion, University of Dundee, Vertex and Zambon. M. Shteinberg has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dexcel, Kamada, Synchrony Medical, Trumed and Zambon. J.D. Chalmers has received grants outside of this work from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead Sciences, Grifols, Insmed, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and Zambon; and is an associate editor of this journal. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

References

Articles from ERJ Open Research are provided here courtesy of European Respiratory Society

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00115-2023

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://openres.ersjournals.com/content/erjor/early/2023/09/28/23120541.00115-2023.full.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/158275860

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1183/23120541.00115-2023

Article citations

Priorities and barriers for research related to primary ciliary dyskinesia.

ERJ Open Res, 10(5):26-2024, 30 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39351388 | PMCID: PMC11440378

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

International BEAT-PCD consensus statement for infection prevention and control for primary ciliary dyskinesia in collaboration with ERN-LUNG PCD Core Network and patient representatives.

ERJ Open Res, 7(3):301-2021, 01 Jul 2021

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 34350277 | PMCID: PMC8326680

Development of a core outcome set for effectiveness trials aimed at optimising prescribing in older adults in care homes.

Trials, 18(1):175, 12 Apr 2017

Cited by: 28 articles | PMID: 28403876 | PMCID: PMC5389003

A core outcome domain set for clinical research on capillary malformations (the COSCAM project): an e-Delphi process and consensus meeting.

Br J Dermatol, 187(5):730-742, 31 Jul 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35762296 | PMCID: PMC9796083

Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative: protocol for an international Delphi study to achieve consensus on how to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a 'core outcome set'.

Trials, 15:247, 25 Jun 2014

Cited by: 150 articles | PMID: 24962012 | PMCID: PMC4082295

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

31

31