Abstract

Free full text

Monoclonal Antibodies Specific for the V2, V3, CD4-Binding Site, and gp41 of HIV-1 Mediate Phagocytosis in a Dose-Dependent Manner

ABSTRACT

In light of the weak or absent neutralizing activity mediated by anti-V2 monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), we tested whether they can mediate Ab-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP), which is an important element of anti-HIV-1 immunity. We tested six anti-V2 MAbs and compared them with 21 MAbs specific for V3, the CD4-binding site (CD4bs), and gp41 derived from chronically HIV-1-infected individuals and produced by hybridoma cells. ADCP activity was measured by flow cytometry using uptake by THP-1 monocytic cells of fluorescent beads coated with gp120, gp41, BG505 SOSIP.664, or BG505 DS-SOSIP.664 complexed with MAbs. The measurement of ADCP activity by the area under the curve showed significantly higher activity of anti-gp41 MAbs than of the members of the three other groups of MAbs tested using beads coated with monomeric gp41 or gp120; anti-V2 MAbs were dominant compared to anti-V3 and anti-CD4bs MAbs against clade C gp120ZM109. ADCP activity mediated by V2 and V3 MAbs was positive against stabilized DS-SOSIP.664 trimer but negligible against SOSIP.664 targets, suggesting that a closed envelope conformation better exposes the variable loops. Two IgG3 MAbs against the V2 and V3 regions displayed dominant ADCP activity compared to a panel of IgG1 MAbs. This superior ADCP activity was confirmed when two of three recombinant IgG3 anti-V2 MAbs were compared to their IgG1 counterparts. The study demonstrated dominant ADCP activity of anti-gp41 against monomers but not trimers, with some higher activity of anti-V2 MAbs than of anti-V3 and anti-CD4bs MAbs. The ability to mediate ADCP suggests a mechanism by which anti-HIV-1 envelope Abs can contribute to protective efficacy.

IMPORTANCE Anti-V2 antibodies (Abs) correlated with reduced risk of HIV-1 infection in recipients of the RV144 vaccine, suggesting that they play a protective role, but a mechanism providing such protection remains to be determined. The rare and weak neutralizing activities of anti-V2 MAbs prompted us to study Fc-mediated activities. We compared anti-V2 MAbs with other MAbs specific for V3, CD4bs, and gp41 for Ab-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) activity, implicated in protective immunity. The anti-V2 MAbs displayed stronger activity than other anti-gp120 MAbs in screening against one of two gp120s and against DS-SOSIP, which mimics the native trimer. The activity of anti-gp41 MAbs was superior in targeting monomeric gp41 but was comparable to that seen against trimers, which may not adequately expose gp41 epitopes. While anti-envelope MAbs in general mediated ADCP activity, anti-V2 MAbs displayed some dominance compared to other MAbs. Our demonstration that anti-V2 MAbs mediate ADCP activity suggests a functional mechanism for their contribution to protective efficacy.

INTRODUCTION

The RV144 vaccine trial was the first clinical study to achieve any degree of protection, reaching a modest efficacy level of 31.2% in HIV vaccine recipients (1, 2). The study revealed that a high titer of plasma anti-V2 antibodies (Abs), particularly immunoglobulin G3 (IgG3) Abs, correlated with a reduced risk of HIV-1 infection (2, 3). The protective V1-V2 IgG3 response was shown to wane quickly, corresponding to the waning vaccine efficacy (4). The concept of a possible role of anti-V2 Abs in protection from HIV-1 infection was further supported by sieve analysis of virus sequences derived from recipients of the RV144 vaccine or a placebo, which suggested that anti-V2 Abs exerted immune pressure on viruses with particular sequence signatures in V2 (5). These results stimulated numerous nonhuman primate studies exploring the potential role of V2 Abs in vaccine-elicited protection. Results revealing serum binding of Abs to V2 were correlated with delayed simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) acquisition following vaccination with a DNA/Ad5-recombinant regimen and intrarectal challenge (6). High-avidity Abs with respect to the V1-V2 region elicited by an SIV human papillomavirus pseudovirion-based vaccine approach correlated with delayed SIV acquisition following repeated low-dose vaginal challenges (7). Protection against intrarectal SIV acquisition following sequential administration of adenovirus- or adenovirus/poxvirus-based vaccines was correlated with serum V2 binding Abs (8). Recently, an SIV rhesus macaque study mimicking the RV144 vaccine regimen demonstrated a correlation of protective efficacy with mucosal IgG Abs against the V2 region (9). Together with the results of the RV144 trial, these repeated findings associating V2 Abs with protection suggest that this immune response has a significant impact on HIV/SIV acquisition.

However, the mechanism by which anti-V2 Abs might exert a protective effect is unknown. In the RV144 trial, neutralizing Abs (nAbs) were not correlated with protection (2, 10). Further, although monoclonal Abs (MAbs) specific for the V2 region are extensively cross-reactive with gp120s derived from subtypes A, B, and C (11), they exhibit weak neutralizing activities and do so only against tier 1 viruses (11,–15). Thus, investigations have focused on nonneutralizing Ab activities. One possible mechanism is the inhibition of gp120 interaction with the α4β7 integrin expressed on Th17 cells by anti-V2 Abs. This interaction is believed to facilitate infection of activated mucosal CD4+ T cells. V2 MAbs target an epitope that overlaps a conserved three-amino-acid motif in the V2 region that is the binding site for α4β7 integrin and may therefore block gp120 interaction with this integrin (12, 16). In support of this hypothesis, mouse anti-V2 MAbs have been shown to inhibit binding of biotinylated gp120MN to the α4β7+ β1− RPMI-8866 B lymphoma cell line (14). Two human anti-V2 MAbs from our laboratory, 697 and 2158, also inhibited binding of gp120MN to CD4+ cells and activated CD8+ cells (17). The extent to which such blocking by V2-specific Abs occurs in vivo is not known; however, it has been reported that the envelopes of most HIV strains do not bind to α4β7 (18), a result that may be dependent upon the nature of the carbohydrate residues on the Env protein. The absence of complex carbohydrates on the viral envelope together with enriched oligomannose-type glycans results in greater binding to α4β7 (19). Thus, more experiments are required to determine if blocking of Env-α4β7 binding contributes to the protective function of anti-V2 MAbs.

A spectrum of Fc-mediated nonneutralizing Ab activities have been associated with HIV and SIV vaccine protective efficacy. These include Ab-dependent cell-mediated viral inhibition (ADCVI) (20,–24), Ab-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) (22,–28), Ab-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) (29), and Ab-dependent complement deposition (ADCD) (29). ADCP and ADCD have undergone extensive investigation only recently. In fact, as state-of-the-art high-throughput technologies are now in use, nonneutralizing Ab activities can be grouped, and protective correlations with polyfunctional Ab activities have been demonstrated (30). With regard to anti-V2 MAbs, a few have been shown to mediate low-level ADCC activity. CH58 and CH59, derived from recipients of the RV144 vaccine, and 697 and 2158, derived from chronically infected individuals, displayed specific killing of virus-infected cells and of target cells pulsed with gp140SF162, respectively (15, 31). In general, however, using sera of HIV-infected people, the variable loops of the viral envelope have been reported not to represent a major ADCC determinant (32). MAbs 697 and 2158 have also been shown to mediate ADCP (31). ADCD by V2 MAbs has not, to our knowledge, been assessed.

In light of the weak or absent neutralizing and ADCC activity mediated by anti-V2 MAbs, we investigated a panel of V2 MAbs for their ability to mediate ADCP, a mechanism potentially associated with protective efficacy. ADCP may contribute more to vaccine-elicited protection than ADCC, particularly in mucosal tissues (33). ADCP was enhanced in recipients of the RV144 vaccine with a high level of IgG3/IgG1 Abs to V1-V2 (34) and was associated with protection in nonhuman primates (29). As ADCP was shown to be a prominent activity of the MAb V2 panel, we further compared it with that of other MAbs specific for V3, the CD4bs, and gp41. All four categories of MAbs mediated ADCP activity. The levels of activity differed between the panels of MAbs and also depended on the target antigens displayed on the beads, with dominant activity mediated by anti-gp41 and some anti-V2 MAbs.

RESULTS

Titration of biotinylated gp120 for coating the beads.

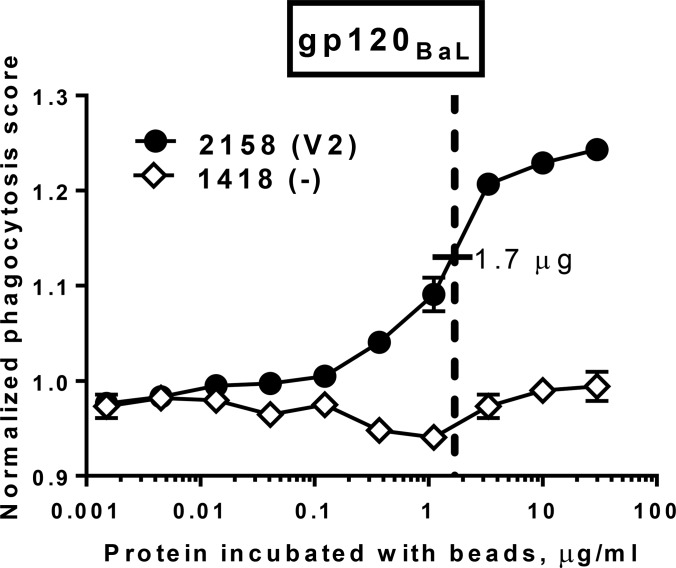

The phagocytic assay used here is based on the ability of an Ab to recognize antigen-coated beads and mediate phagocytosis by THP-1 cells. Given that the amount of gp120 bound to the surface of the beads is an important factor for assay sensitivity, we titrated the biotinylated recombinant gp120BaL used for coating from 30 to 0.0015 μg/ml using 3-fold dilutions (Fig. 1). The phagocytic activity mediated by human anti-V2 MAb 2158, but not that by the irrelevant human MAb 1418 against parvovirus B19 as a negative control, was dose dependent. There was some plateauing of phagocytic activity, corresponding to maximal activity at 3.3 to 30.0 μg/ml. Thereafter, we used 1.7 μg/ml for coating the beads with gp120 whereas gp41 was used at 0.6 μg/ml to match the molecular weight of gp120.

Titration of gp120BaL coated onto beads. Ten serial 3-fold dilutions of recombinant gp120BaL were used for coating the beads to test phagocytosis mediated by MAb 2158 (anti-V2) and negative-control MAb 1418 (anti-parvovirus B19). A suboptimal dose of 1.7 μg/ml of gp120 was used for coating the beads in the study.

Binding of MAbs to gp120 and gp41.

All 27 MAbs (Table 1) were screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for their reactivity to gp120 (20 MAbs), SOSIP (27 MAbs), or gp41 (7 MAbs) to confirm their binding specificity. The majority of MAbs displayed strong binding to the respective proteins, with a few exceptions: 697 (anti-V2), 447-52D (anti-V3, GPGR specific), and 654 (anti-CD4bs) bound relatively weakly to gp120ZM109, while some anti-gp41 MAbs bound weakly to SOSIP (Table 2).

TABLE 1

List of human anti-HIV-1 gp120 and gp41 MAbs used in the study

| MAb no. or description | MAb designation | Specificity | Isotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 697 | V2 | IgG1(λ) | 12 |

| 2 | 830A | V2 | IgG3(κ) | 35 |

| 3 | 1357 | V2 | IgG1(κ) | 36 |

| 4 | 1361 | V2 | IgG1(κ) | 36 |

| 5 | 1393A | V2 | IgG1(κ) | 35 |

| 6 | 2158 | V2 | IgG1(κ) | 37 |

| 7 | 447-52D | V3 | IgG3(λ) | 38 |

| 8 | 2191 | V3 | IgG1(λ) | 39 |

| 9 | 2219 | V3 | IgG1(λ) | 39 |

| 10 | 2442 | V3 | IgG1(λ) | 39 |

| 11 | 2558 | V3 | IgG1(λ) | 40 |

| 12 | 3074 | V3 | IgG1(λ) | 41 |

| 13 | 3869 | V3 | IgG1(λ) | 42 |

| 14 | 4682 | V3 | IgG1(λ) | 43 |

| 15 | 559/64-D | CD4bs | IgG1(κ) | 44 |

| 16 | 654-D | CD4bs | IgG1(λ) | 45 |

| 17 | 729-D | CD4bs | IgG1(κ) | 46 |

| 18 | 1202 | CD4bs | IgG1(κ) | 45 |

| 19 | 1331E | CD4bs | IgG1(κ) | 36 |

| 20 | 1570 | CD4bs | IgG1(λ) | 47 |

| 21 | 126-7 | gp41 | IgG1(λ) | 48 |

| 22 | 167 | gp41 | IgG1(λ) | 48 |

| 23 | 240 | gp41 | IgG1(κ) | 48 |

| 24 | 246 | gp41 | IgG1(κ) | 48 |

| 25 | 1281 | gp41 | IgG1(λ) | 36 |

| 26 | 1342 | gp41 | IgG1(λ) | 36 |

| 27 | 1367 | gp41 | IgG1(λ) | 36 |

| Ctr.a | 1418 | Parvovirus B19 | IgG1(κ) | 49 |

TABLE 2

ADCP and binding activities of MAbs tested in the studya

| Site and MAb no. | MAb designation | ADCP score | ELISA OD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gp120BaL | gp120ZM109 | SOSIP | DS-SOSIP | BSA | gp120BaL | gp120ZM109 | SOSIP | BSA | ||

| V2 | ||||||||||

1 1 | 697 | 1.13 | 1.20 | 1.06 | 1.14 | 0.90 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 3.9 | 0.1 |

2 2 | 830A | 1.34 | 1.36 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 0.99 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 0.1 |

3 3 | 1357 | 1.29 | 1.25 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 0.1 |

4 4 | 1361 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 0.98 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 0.1 |

5 5 | 1393A | 1.24 | 1.27 | 1.11 | 1.20 | 0.97 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 0.1 |

6 6 | 2158 | 1.24 | 1.36 | 1.12 | 1.28 | 0.96 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 0.1 |

| V3 | ||||||||||

7 7 | 447-52D | 1.39 | 1.28 | 1.06 | 1.56 | 0.98 | 3.5 | 1.6 | 3.8 | 0.1 |

8 8 | 2191 | 1.19 | 1.21 | 1.07 | 1.20 | 0.97 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 0.1 |

9 9 | 2219 | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.20 | 1.03 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 0.1 |

10 10 | 2442 | 1.11 | 1.18 | 1.09 | 1.23 | 1.08 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 0.1 |

11 11 | 2558 | 1.15 | 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.24 | 0.92 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 0.1 |

12 12 | 3074 | 1.23 | 1.05 | 1.13 | 1.36 | 1.00 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 0.1 |

13 13 | 3869 | 1.09 | 1.10 | 1.01 | 1.19 | 0.89 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 4 | 0.1 |

14 14 | 4682 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.10 | 1.25 | 1.01 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 4.2 | 0.1 |

| CD4bs | ||||||||||

15 15 | 559/64 | 1.04 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.08 | 0.94 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 0.1 |

16 16 | 654 | 1.22 | 1.13 | 0.98 | 1.10 | 0.93 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 0.1 |

17 17 | 729 | 1.12 | 1.14 | 1.00 | 1.12 | 0.99 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 0.1 |

18 18 | 1202 | 1.12 | 1.14 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 0.1 |

19 19 | 1331E | 1.33 | 1.19 | 1.04 | 1.14 | 1.02 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 0.1 |

20 20 | 1570 | 1.21 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 1.26 | 0.95 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 0.1 |

| gp41 | gp41ZA.1197 | gp41HXB2 | SOSIP | DS-SOSIP | BSA | gp41ZA.1197 | gp41HXB2 | SOSIP | BSA | |

21 21 | 126-7 | 1.31 | 1.80 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 1.09 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 0.1 |

22 22 | 167 | 1.34 | 1.45 | 1.06 | 1.24 | 0.96 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 0.1 |

23 23 | 240 | 1.35 | 1.78 | 1.02 | 1.20 | 1.01 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 0.1 |

24 24 | 246 | 1.38 | 1.52 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 0.88 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 0.1 |

25 25 | 1281 | 1.23 | 1.74 | 1.08 | 1.21 | 1.03 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 1.4 | 0.1 |

26 26 | 1342 | 1.36 | 1.40 | 1.09 | 1.17 | 0.99 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 0.1 |

27 27 | 1367 | 1.32 | 1.53 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 0.92 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

Phagocytic activity of MAbs against gp120-, gp41-, and SOSIP-coated beads.

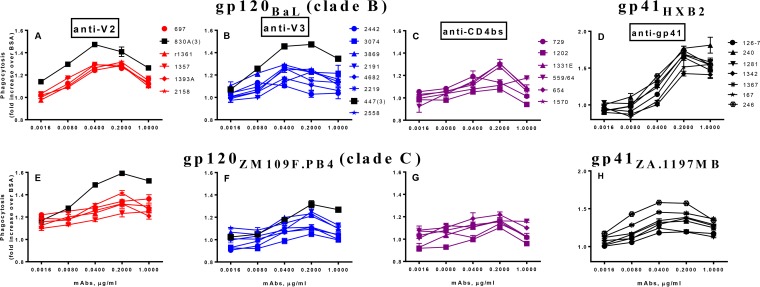

The main goal of this study was to determine whether the phagocytic activity mediated by human anti-V2 MAbs has any special characteristics compared to that mediated by MAbs against V3, CD4bs, and gp41 which could explain the possible protective function of these V2 Abs observed in the RV144 vaccine clinical trial (2). We tested 25 IgG1 and two IgG3 MAbs (Table 1) produced by hybridoma cell lines which preserved the Fc fragments of the original donors. The V2, V3, and CD4bs MAbs were first tested against two recombinant gp120 proteins (BaL [clade B] and ZM109F.PB4 [clade C]) for phagocytic activity, while the gp41 MAbs were tested against two gp41 proteins (HXB2 [clade B] and ZA.1197 [clade C]) (Fig. 2). The recombinant proteins were produced in 293T cells which preserved typical human glycosylation. All MAbs were titrated at between 1 and 0.0016 μg/ml, and the majority mediated phagocytosis with a peak of activity at 0.2 μg/ml (Fig. 2; Table 2). All MAbs were reactive with the antigens and exhibited strong binding to gp120, gp41, and SOSIP (Table 2).

Phagocytosis activity of human anti-HIV-1 envelope MAbs. Four panels of MAbs against V2, V3, CD4bs, and gp41 were tested in five dilutions starting at 1 μg/ml. The beads were coated with gp120BaL (A to C) or gp41HXB2 (D) (both clade B) or with gp120ZM109F.PB4 (E to G) or gp41ZA.1197MB (H) (both clade C). All MAbs were IgG1, with the exception of two IgG3 MAbs, 830A and 447 (labeled γ3). Phagocytosis data indicate fold increases of scores over those determined for beads coated with BSA.

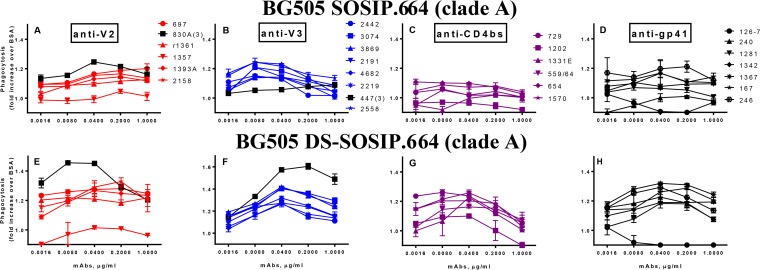

To further evaluate the ADCP activity of MAbs against beads coated with proteins which mimic the trimers on the virus surface, we utilized two recombinant proteins: BG505 SOSIP.664 and its version with a stabilized conformation (201C 433C variant), BG505 DS-SOSIP.664 gp140 (coated on the beads at 1.7 μg/ml). V2 and V3 MAbs exhibited higher ADCP activity against the SOSIP trimer than the anti-CD4bs MAbs (Fig. 3A to toC).C). Interestingly, V2 and V3 MAbs mediated better ADCP against DS-SOSIP (Fig. 3E and andF),F), the version of the trimer that does not change conformation upon interaction with CD4 (50). CD4bs MAbs again mediated lower ADCP than the V2 and V3 MAbs, although some exhibited moderate activity against DS-SOSIP (Fig. 3G). Only some of the gp41 MAbs mediated ADCP activity against SOSIP-coated beads (Fig. 3D), but most showed higher levels against DS-SOSIP (Fig. 3H). Overall, the ADCP activity levels of the gp41 MAbs were much lower against these trimer mimics than against gp41 proteins (Fig. 2D and andHH).

Phagocytosis activity of MAbs against BG505 SOSIP.664 and BG505 DS-SOSIP.664 gp140 trimers. Four panels of MAbs against V2, V3, CD4bs, and gp41 (from left to right) were tested using beads coated with BG505 SOSIP.664 (A to D) and with BG505 DS-SOSIP.664 (E to H). All MAbs were IgG1, except two IgG3(γ3) MAbs (labeled in black in panels A, B, E, and F).

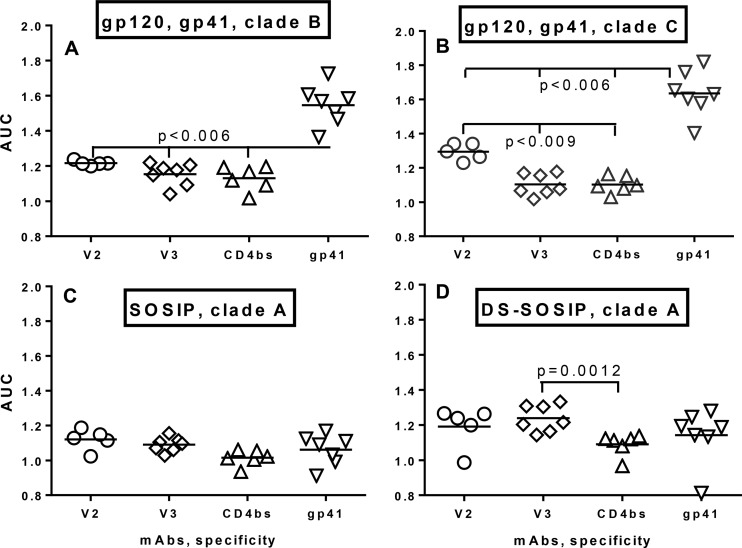

In order to evaluate the differences in ADCP activity mediated by the various MAbs, analyses of the area under the curve (AUC) were conducted (Fig. 4). The ADCP activity of anti-V2 MAbs was comparable to the activity of anti-V3 and anti-CD4bs in the assay using beads coated with gp120BaL (Fig. 4A) and was significantly higher (P < 0.009) using gp120ZM109F.PB4 (Fig. 4B). The anti-gp41 MAbs were tested against two gp41 proteins representing strains that were different from the gp120s used to coat the beads but also belonging to either clade B (HXB2) (Fig. 4A) or clade C (ZA.1197) (Fig. 4B). The ADCP activities of anti-gp41 MAbs were significantly higher than those of the V2, V3, and CD4bs MAbs tested against gp120 from clade B and clade C (P < 0.006) (Fig. 4A and andBB).

Area under the curve analysis of ADCP activity of MAbs. Panels of IgG1 MAbs were tested against beads coated with gp120BaL and gp41HXB2, clade B (A); gp120ZM109F.PB4 and gp41ZA.1197MB, clade C (B); SOSIP, clade A (C); and DS-SOSIP, clade A (D). The two IgG3 MAbs shown in Fig. 2 were excluded from this analysis. The statistical significance of the differences in the results was determined using the two-way nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

AUC analysis of ADCP against the SOSIP trimer showed comparable ADCP activities for all 4 classes of MAb (Fig. 4C). ADCP activity levels of the MAbs against DS-SOSIP were somewhat higher for the V2 and V3 MAbs (Fig. 4B). The V3 MAbs exhibited significantly elevated ADCP activity compared to the CD4bs Abs (P = 0.0012) (Fig. 4D) which was also comparable to that of the V2 and gp41 MAbs.

ADCP activity of IgG3 and IgG1 MAbs.

The Fc components of IgG subclasses use different Fcγ receptors and may mediate different activities. Indeed, two IgG3 MAbs tested here, the anti-V2 MAb (830A) and the anti-V3 MAb (447-52D), exhibited dominant ADCP activity in the panels of anti-V2 and anti-V3 MAbs shown (Fig. 2A, ,B,B, ,E,E, and andFF and and3A,3A, ,E,E, and andF).F). The reason for the poor ADCP activity of the 447-52D antibody against SOSIP-coated beads (Fig. 3B) is not known but presumably reflects poor binding to the clade A antigen.

In order to assess the ability of IgG3 MAbs to potently engage the THP-1 effector cells in the ADCP assay due to strong binding to Fcγ receptors and not to other factors, three anti-V2 MAbs were produced as recombinant Abs in the form of IgG1 and IgG3 variants and were compared in the ADCP assay. The 830A MAb was originally IgG3 and was switched to IgG1, while MAbs 1361 and 2158 were originally IgG1 and were switched to IgG3.

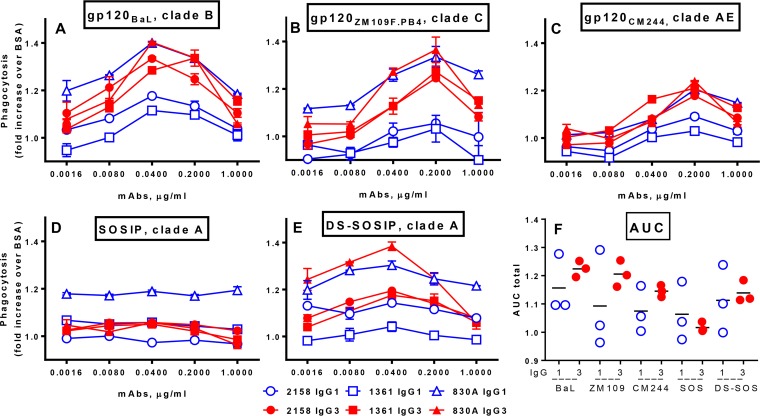

The three pairs of IgG1 and IgG3 recombinant variants were titrated and tested using beads coated with HIV gp120 proteins of BaL (clade B), ZM109F.PB4 (clade C), and CM244 (clade AE) (Fig. 5A to toC),C), as well as beads coated with clade A SOSIP and DS-SOSIP (Fig. 5D and andE).E). While limited ADCP activity was seen with the SOSIP-coated beads, in all other assays the V2 MAbs that were originally IgG1 but had been switched to IgG3 exhibited elevated ADCP activity in the IgG3 form (Fig. 5A to toCC and andE).E). In contrast, the 830A antibody, originally IgG3 but switched to IgG1, retained the same high ADCP activity level in its IgG1 form. AUC analysis revealed that the ADCP activities for the IgG3 variants tended to be higher than those for the corresponding IgG1 variants for all three gp120 molecules tested as well as for DS-SOSIP (Fig. 5F). The high activity of the 830A IgG1 MAb presumably prevented attainment of statistical significance. A larger panel of antibodies will be necessary to confirm the superior functioning of IgG3 over IgG1 recombinant Abs in mediating phagocytic activity in vitro.

ADCP activity of three pairs of recombinant anti-V2 MAbs with Fc regions switched between IgG1 and IgG3. MAbs 2158 and 1361 were switched from IgG1 to IgG3, while MAb 830A was switched from IgG3 to IgG1; IgG1 is indicated as an open symbol (blue) and as IgG3 is a solid symbol (red). The MAbs were tested against beads coated with gp120BaL (A), gp120ZM109F.PB4 (B), gp120CM244 (C), SOSIP (D), and DS-SOSIP (E). (F) The data were analyzed using area under the curve data.

DISCUSSION

This study addressed the issue of whether anti-V2 MAbs can mediate ADCP activity, since V2 Abs had been previously shown to contribute to vaccine-induced protection in nonhuman primate experiments (29) and human vaccine trials (2, 3). If so, it would suggest a possible mechanism for the correlation of anti-V2 Abs with the reduced risk of HIV-1 infection observed in nonhuman primate vaccinees and in recipients of the RV144 vaccine. The results of the studies described here showed that anti-V2 MAbs mediate ADCP activity in a dose-dependent fashion. The anti-V2 MAbs exhibited ADCP activity similar to that of anti-V3 and CD4bs MAbs against clade B gp120 but displayed elevated activity against clade C gp120 compared to the other two MAb groups, suggesting broader recognition of exposed epitopes. Anti-gp41 MAbs were more effective overall in mediating ADCP against their appropriate gp41-coated beads than the other MAbs against their gp120 targets, but the results were comparable using gp140 trimers. The gp41 epitopes recognized are likely less exposed on SOSIP and DS-SOSIP trimers due to the presence of gp120, which can shield most of them. Anti-V2 MAbs also exhibited significant ADCP activity against the DS-SOSIP trimer (but not the SOSIP trimer), as did anti-V3 and anti-gp41 MAbs but not anti-CD4bs MAbs. Our results support the notion that the ADCP activity of anti-V2 Abs may have contributed to protection from HIV-1 infection in the RV144 trial.

The Ab isotype/subclass can modulate both epitope specificity and antiviral activity (51). Moreover, IgG3 has been shown to mediate better Fc effector function than other IgG subclasses (52). Therefore, in further evaluating the anti-V2 MAbs, we examined subclass differences. Results of experiments using three pairs of anti-V2 MAbs, with each pair including IgG1 and IgG3 variants (Fig. 5), were consistent with the possible contribution of ADCP to the protective efficacy against HIV-1 acquisition observed in the RV144 trial. Analysis of the RV144 data revealed that the presence of vaccine-elicited Abs of the IgG3 subclass specific for V1-V2 fusion proteins was correlated with reduced risk of HIV-1 infection (4). Given that the IgG3 anti-V2 MAb 830A does not display higher neutralizing activity than IgG1 anti-V2 MAbs (11), the ADCP activity of the IgG3 anti-V2 MAbs shown here, which tended to be higher than that of the corresponding IgG1 MAbs, suggests that this Fc-mediated activity may contribute more to protective efficacy than the weak neutralizing activity of anti-V2 MAbs against tier 1 viruses (11). Indeed, the protective role of anti-V2 Abs against HIV-1 infection may eventually prove to be polyfunctional. It may include other functions not explored here, such as additional Fc receptor-related activities and/or the inhibition of the gp120/α4β7 interaction which has been shown previously despite some remaining controversy (14, 17, 18).

Given that one of the main goals of the vaccine field is to elicit broadly neutralizing Abs (bnAbs), we sought to determine if an antigen designed to elicit such bnAbs would also be a target for a nonneutralizing activity, such as ADCP. As shown in Fig. 3 and and4,4, ADCP activity was poor against SOSIP targets whereas the conformationally constrained DS-SOSIP was a better target for this activity. It has previously been shown that nonneutralizing CD4bs MAbs poorly bound to SOSIP trimers (53), so it was not surprising that the CD4bs group of MAbs poorly mediated ADCP against these antigens. Interestingly, ADCP was better mediated by anti-V2, anti-V3, and anti-gp41 MAbs against DS-SOSIP targets, suggesting that the lack of conformational changes to the trimer resulted in better accessibility of the MAbs to the targeted epitopes. This may indicate that nonneutralizing Abs can act better against a consistent, relatively immobile antigen.

In order to control for day-to-day variability in ADCP assays, we normalized the phagocytic scores to background values (obtained with antigen-coated beads and THP-1 cells without serum) and then reported all results as the fold increase in the normalized value in comparison to that of ADCP against bovine serum albumin (BSA)-coated beads. Thus, the results show relatively modest values unlike the higher phagocytic scores reported without normalization (54). The modest values may also result from the small amount of gp120 and gp41 coated onto the beads. The assay was validated by the dependence of phagocytic activity on the dose of antigen coated on the beads as shown in Fig. 1. We chose a suboptimal dose of gp120 and a similar molar concentration of gp41 for coating the beads; this may mimic the low density of trimeric spikes on the virus envelope. Thus, despite the relatively low density of Env proteins on the beads, the observed ADCP activity mediated by the MAbs supports the concept that this function may also take place in vivo against HIV-1 infection.

ADCP can play an important role in antiviral immunity because it can engage several effector cells expressing three isoforms of FcγRs, including FcγIIa with medium affinity and also FcγIa and FcγIIIa (55). ADCP has been shown to have a protective function, clearing influenza and West Nile viruses (56, 57). In HIV infection, nonneutralizing Abs develop in less time and with less somatic hypermutation than neutralizing Abs (58, 59). Thus, they can respond significantly more quickly than bnAbs, making them very important in the initial immunological response to HIV infection. However, while ADCP develops relatively early in HIV infection (60), due to decreased Fc receptor expression on phagocytic cells with disease progression, its clearing efficiency can be affected (61). Therefore, ADCP mediated by vaccine-induced Abs against HIV-1 may be a particularly important protective correlate, as has been shown in vaccinated rhesus macaques (29).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that human MAbs specific to several regions of the HIV-1 envelope, in spite of undetectable or weakly neutralizing activity, mediated ADCP activity in an in vitro assay. Depending on the HIV clade tested, the ADCP activity of anti-V2 MAbs displays some dominance over that of anti-V3 and anti-CD4bs MAbs. The activity of anti-gp41 MAbs is the most dominant using monomers but is comparable with that of other MAbs using gp140 trimers. The IgG3 MAbs are particularly effective in mediating ADCP compared to the corresponding IgG1 variants. Moving forward, elicitation of nonneutralizing Ab activities such as ADCP should be sought in conjunction with bnAbs in HIV vaccination strategies, as they appear to contribute to protection and are potentially more easily elicited than bnAbs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Monoclonal antibodies.

Twenty-seven human MAbs specific for V2 (n = 6), V3 (n = 8), CD4bs (n = 6), and gp41 (n = 7) were tested in this study; the panel contained 25 IgG1 MAbs and 2 IgG3 MAbs (Table 1). All of these MAbs were derived from chronically HIV-1-infected individuals and were generated using the hybridoma technology based on fusion of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformed lymphocytes with the heteromyeloma cell line SHM-D33 (62). In light of the significant changes that differential glycosylation can impart to Fc effector function, especially ADCP (31), it was important that all Abs were produced in the same manner, with the exception of MAb 1361, which was used in recombinant form (r1361). Twenty-three MAbs were derived from individuals living primarily in the New York City area who were presumably infected with subtype B viruses, while four MAbs (2558, 3074, 3869, and 4682) originated from individuals infected with non-clade B viruses and living in Cameroon.

Recombinant proteins.

Three recombinant gp120s, BaL (clade B), ZM109F.PB4 (clade C), and CM244 (CRF01-AE), and two gp41 proteins, HXB2 (clade B) and ZA.1197MB (clade C), were purchased from Immune Technology Corp. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was purchased from Sigma. gp140 trimers of two recombinant proteins, BG505 SOSIP.664 (clade A) and conformationally fixed BG505 DS-SOSIP.664 (201C 433C variant), were produced by transiently transfected 293F cells as previously described (63). Briefly, 293F cells were transfected using polyethylenimine HCl MAX (PEI-MAX) (1 mg/ml) in water mixed with expression plasmids for SOSIP.664 or DS-SOSIP.664, Furin (kindly provided by Peter Kwong and M. Gordon Joyce), and Opti-MEM. For one flask, 600 μg of Env plasmid, 150 μg of Furin plasmid, and 3 mg of PEI-MAX were added to 550 ml of growth media. Culture supernatants were harvested 72 h after transfection.

Binding assay (ELISA).

The MAbs were screened by standard ELISA against the recombinant gp120 and gp41 antigens used in the ADCP assay to confirm their binding activity. In short, proteins were coated directly onto Immulon 2HB plates at a concentration of 1 μg/ml. Following overnight incubation, the plates were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20 and blocked with assay diluent (PBS containing 2.5% bovine serum albumin and 7.5% fetal bovine serum). Monoclonal Abs (1 μg/ml) were added and incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C. Plates were washed again before bound Abs were detected by incubation with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (γ specific) (Southern Biotech), followed by washing and addition of substrate to develop color. The plates were read at 405 nm.

Ab-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) assay.

ADCP activity was measured as previously described (64) with minor modifications. In short, gp120 (BaL [clade B], ZM109 [clade C], and CM244 [clade AE]), gp41 (ZA.1197MB, clade C), gp41 (HXB2, clade B), BG505 SOSIP.664, BG505 DS-SOSIP.664, and BSA were biotinylated with a Biotin-XX microscale protein labeling kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and incubated with a 100-fold dilution of 1 μg yellow-green streptavidin-fluorescent beads (Life Technologies) for 25 min at room temperature in the dark. The diameter of the beads is 1 μm, which is approximately 5 times the size of a virus. Dilutions of each MAb were added to 400,000 THP-1 cells (monocytic cell line) in a 96-well U-bottom plate. The bead-gp120 mixture was further diluted 5-fold in R10 media, and 50 μl was added to the cells and incubated for 3 h at 37°C. At the end of incubation, 70 μl 2% paraformaldehyde was added to fix the samples. Cells were then assayed for fluorescent bead uptake by flow cytometry using a BD Biosciences LSRII flow cytometer. The phagocytic score of each sample was calculated by multiplying the percentage of bead-positive cells (frequency) by the degree of phagocytosis measured as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and dividing by 106. Values were normalized to background values (cells and beads without serum) by dividing the phagocytic score of the test sample by the phagocytic score of the background sample to ensure consistency in the values obtained on different assay days. As indicated in the figure legends, we report either this normalized phagocytosis score or, alternatively, the fold increase in phagocytosis against beads coated with test antigen compared to phagocytosis against BSA-coated beads.

Production of recombinant IgG1 and IgG3 anti-V2 MAbs.

Two anti-V2 IgG1 MAbs, 1361 and 2158, were switched to IgG3, and one anti-V2 IgG3 MAb, 830A, was changed to IgG1. The recombinant Abs were produced according to methods used in our laboratory (65, 66). In brief, total RNAs were isolated from hybridoma cell lines producing three MAbs, and cDNAs were synthesized by reverse transcription of mRNAs. The variable genes of heavy chains (VH) and light chains (VL) were amplified by PCR using specific primers for different immunoglobulin (Ig) genes of Abs and cDNAs synthesized from different Abs as the templates. The PCR products were then purified, sequenced, and digested with restriction enzymes which were introduced by the primers. VH genes were digested with restriction enzymes AgeI and SalI, while VL genes were digested with AgeI and BsiWI for kappa chain and XhoI for lambda chain. Finally, the digested VH and VL genes were ligated into IgG-AbVec expression vectors (kindly provided by Michel C. Nussenzweig, Rockefeller University, New York, NY). The VH genes were separately cloned into Igγ1 and Igγ3 expression vectors containing IgG1 or IgG3 Ig constant regions. The IgG3 expression vector was converted from an Igγ1 vector by replacing Cγ1 with a Cγ3 gene sequence. Both the VH and VL plasmids were used for cotransfection of 293T cells to produce recombinant IgG1 and IgG3 MAbs after 4 days of culture. The culture supernatants were harvested, and IgG Abs were purified by the use of protein G chromatography columns (GE Healthcare). The IgG concentrations were determined by quantitative ELISA (67).

Statistical analysis.

Area under the curve (AUC) analysis was used to determine the ADCP activity of MAbs, and the total areas were compared by the two-way nonparametric Mann Whitney test to determine statistical significance (GraphPad Prism).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Peter Kwong and M. Gordon Joyce for the BG505 SOSIP.664 and BG505 DS-SOSIP.664 plasmids and for the VRC 3965 pCDNA3.1(-) Furin (human) plasmid for coexpression with SOSIP.664 and for helpful advice on the expression and purification of the trimers. We thank Yan Zheng and Xiaomei Liu for technical assistance and Irene Kalisz, Advanced BioScience Laboratories, Inc., for preparation of the SOSIP and DS-SOSIP trimers.

This study was supported by NIH grants AI112546 (M.K.G.) and P01 AI100151 (S.Z.-P.); by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; and by the Department of Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

We have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

Articles from Journal of Virology are provided here courtesy of American Society for Microbiology (ASM)

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.02325-16

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://jvi.asm.org/content/jvi/91/8/e02325-16.full.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1128/jvi.02325-16

Article citations

Characterization of antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis in patients infected with hepatitis C virus with different clinical outcomes.

J Med Virol, 96(1):e29381, 01 Jan 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38235622 | PMCID: PMC10953302

Complement is activated by elevated IgG3 hexameric platforms and deposits C4b onto distinct antibody domains.

Nat Commun, 14(1):4027, 07 Jul 2023

Cited by: 11 articles | PMID: 37419978 | PMCID: PMC10328927

Viral vector delivered immunogen focuses HIV-1 antibody specificity and increases durability of the circulating antibody recall response.

PLoS Pathog, 19(5):e1011359, 31 May 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37256916 | PMCID: PMC10284421

Nanobody-mediated complement activation to kill HIV-infected cells.

EMBO Mol Med, 15(4):e16422, 17 Feb 2023

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 36799046 | PMCID: PMC10086584

Antibody Recognition of CD4-Induced Open HIV-1 Env Trimers.

J Virol, 96(24):e0108222, 30 Nov 2022

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 36448805 | PMCID: PMC9769388

Go to all (30) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Plasticity and Epitope Exposure of the HIV-1 Envelope Trimer.

J Virol, 91(17):e00410-17, 10 Aug 2017

Cited by: 30 articles | PMID: 28615206 | PMCID: PMC5553165

A novel human antibody against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 is V1, V2, and V3 loop dependent and helps delimit the epitope of the broadly neutralizing antibody immunoglobulin G1 b12.

J Virol, 77(12):6965-6978, 01 Jun 2003

Cited by: 48 articles | PMID: 12768015 | PMCID: PMC156200

A broad range of mutations in HIV-1 neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies specific for V2, V3, and the CD4 binding site.

Mol Immunol, 66(2):364-374, 18 May 2015

Cited by: 23 articles | PMID: 25965315 | PMCID: PMC4461508

HIV-specific antibody immunity mediated through NK cells and monocytes.

Curr HIV Res, 11(5):388-406, 01 Jul 2013

Cited by: 40 articles | PMID: 24191935

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIAID NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: P01 AI100151

Grant ID: R01 AI112546

NIH (2)

Grant ID: AI100151

Grant ID: AI112546

b

b