Abstract

Free full text

What Makes a pDC: Recent Advances in Understanding Plasmacytoid DC Development and Heterogeneity

Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional antigen presenting cells (APCs) that originate in the bone marrow and are continuously replenished from hematopoietic progenitor cells. Conventional DCs (cDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) are distinguished by morphology and function, and can be easily discriminated by surface marker expression, both in mouse and man. Classification of DCs based on their ontology takes into account their origin as well as their requirements for transcription factor (TF) expression. cDCs and pDCs of myeloid origin differentiate from a common DC progenitor (CDP) through committed pre-DC stages. pDCs have also been shown to originate from a lymphoid progenitor derived IL-7R+ FLT3+ precursor population containing cells with pDC or B cell potential. Technological advancements in recent years have allowed unprecedented resolution in the analysis of cell states, down to the single cell level, providing valuable information on the commitment, and dynamics of differentiation of all DC subsets. However, the heterogeneity and functional diversification of pDCs still raises the question whether different ontogenies generate restricted pDC subsets, or fully differentiated pDCs retain plasticity in response to challenges. The emergence of novel techniques for the integration of high-resolution data in individual cells promises interesting discoveries regarding DC development and plasticity in the near future.

Introduction

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and two major subsets of conventional dendritic cells (cDC1 and cDC2) have been identified in mice and humans as well as other mammalian species including non-human primates and pigs, with high similarities between species (1–3). cDC subsets recognize both extracellular and intracellular pathogens, efficiently process and present exogenous antigens to naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and elicit effective adaptive immunity. pDCs are highly effective in sensing intracellular viral or self DNA and RNA mainly via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and rapidly producing large amounts of type I and III interferons (IFNs) (4). Thus, they play an important role in antiviral immunity and systemic autoimmunity (5–8). pDCs are distinguished from cDC subsets by expression of surface markers CD45R (B220), CD45RA, Ly-6C, Siglec-H, and BST2 (CD317) in the mouse and CD303 (BDCA2), CD304 (BDCA4), CD123 (IL-3R), and CD45RA in humans.

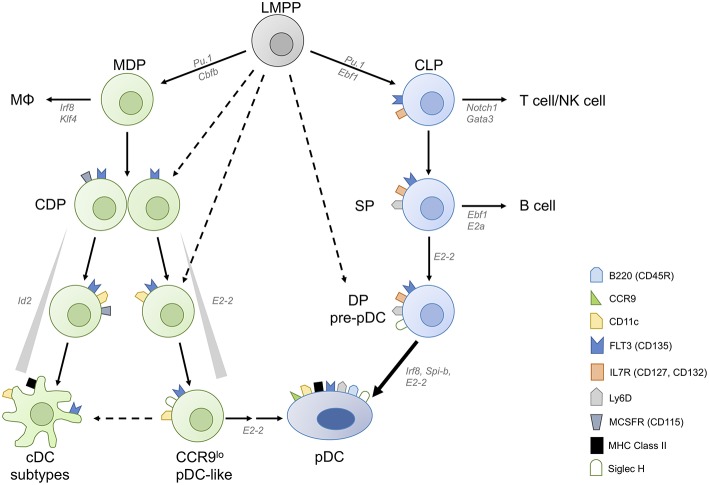

DC subpopulations originate from proliferating progenitor cells in the bone marrow (BM) and require fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (FLT3L)–FLT3 interaction for their development. Lin− FLT3+ c-Kitlow/int M-CSFR+ murine BM cells, so called common DC progenitors (CDP), which are derived from the myeloid macrophage DC progenitors (MDP) or lymphoid primed multipotent progenitors (LMPP), were shown to be DC-committed and to generate pDCs, cDC1 and cDC2 [Figure 1, (9, 10)]. Clonal assays and subsequent single cell transcriptome and imaging analyses demonstrated that the majority of CDPs are already pre-committed to pDC or cDC subsets (9–13). This is also the case for the pre-cDCs, which already contain pre-cDC1, and pre-cDC2 (13, 14). In contrast, pDCs are also produced from a lymphoid progenitor (LP) (15) in the steady state whereas this happens for cDCs only in situation of cDC ablation (16).

Converging plasmacytoid dendritic cell differentiation pathways. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) can be derived from both myeloid and lymphoid progenitors. Common DC progenitors (CDPs) arise from lymphoid primed multipotent progenitors (LMPPs) either directly or via macrophage-DC progenitors (MDPs). CDPs contain precursor cells committed to conventional DC (cDC) and plasmacytoid DC fates, and M-CSFR− CDPs have higher pDC potential than M-CSFR+ CDPs. A fraction of CDPs can give rise to CCR9low pDC-like precursor cells and then CCR9high pDCs in an E2-2 dependent manner. pDC-like cells retain the potential to differentiate into cDCs as well as CCR9high mature pDCs. Inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (Id2), which inhibits E2-2 activity, needs to be suppressed to allow pDC differentiation. pDCs are also generated via the lymphoid pathway, from IL-7R+ lymphoid progenitors (LPs) which give rise to Ly-6D single positive (SP) LP and subsequently to Ly-6D Siglec-H double positive (DP) pre-pDC, terminally committed to the pDC fate.

DC subpopulations can be defined by their ontogeny and by the requirement of specific transcription factors (TF) for their development. pDCs require high-level expression of IRF-8, TCF-4 (also known as E2-2) and BCL-11A for their development, functional specification and maintenance (17–21). Expression of DNA-binding protein inhibitor ID-2, which prevents the activity of the major pDC TF E2-2, needs to be suppressed to allow the generation of pDCs from CDPs (22, 23). On the other hand, the major cDC branches can be distinguished by distinct requirements for IRF-8 (for cDC1) and IRF-4 (for cDC2) (14, 24–27).

DC subpopulations are also distinguished by a high degree of functional specialization (28). While cDC1 efficiently cross-present antigens to CD8+ T cells (27, 29, 30) and produce high levels of IL-12p70, thus promoting cytotoxic T cells and Th1 cells (31, 32), cDC2 are superior in presenting antigens on MHC class II, supporting Th1, Th2, and Th17 polarization (26, 27, 33). pDCs participate in the first line of defense against viral infections by acting as innate effector cells, which initiate IFN-induced antiviral responses in adjacent cells and recruit cytotoxic NK cells (5). Resting pDCs are weak antigen presenting cells and in contrast to cDCs do not prime naïve T cells. After activation, pDCs can acquire the capacity to present antigens and activate T cells directly. Their ability to prime T cells, thus performing truly like DCs, is debated and complicated by the finding that pDC-like cells, which were shown to be related to cDCs (13, 15, 34, 35) have been included in the pDC population in many functional studies, as discussed below. By producing cytokines and chemokines activated pDCs modulate T cell responses elicited by cDCs (5). During viral infection pDCs were shown to cooperate with cDC1 in lymph nodes, promoting their maturation and cross-presentation activity to induce antiviral CD8+ T cells (36). But there is also evidence for a role of pDCs in the induction of immune tolerance by generation of hyporesponsive and regulatory T cells (37–39).

Recent technological developments have allowed unprecedented resolution, down to the single cell level, in the analysis of cell transcriptomes as well as in in vivo lineage tracing, overcoming the limitations of discrimination based solely on surface markers (40–44). The characterization of transcriptional profiles of individual cells (13, 42, 45) and more recently the integrated analysis of single cell transcriptome and chromatin accessibility (46) has revealed unexpected heterogeneity and signs of very early lineage priming of individual hematopoietic BM progenitor cells, which were previously considered multi- or oligopotent. For example, single cell barcoding and tracing showed that DC and even pDC commitment can already be imprinted in early LMPP and at the HSPC stage (12, 41, 47). cDC subtype specification was detected already at the CDP and pre-cDC stage of development (12–14). In some instances, these analyses led to the definition of more stringent surface marker combinations that allow the discrimination of largely committed progenitor cells within the “oligopotent” population (13, 15).

Combining CRISPR/Cas9-based genomic perturbation with transcriptome profiling in the same cells revealed differentiation trajectories and regulatory networks during hematopoiesis (40, 48). Integration of clonal labeling and lineage tracing experiments and single cell time-lapse imaging experiments may lead to a better understanding of immune cell differentiation dynamics and regulation in the future (11, 40, 43, 49).

Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Development From Myeloid and Lymphoid Progenitors

Early works indicated that DCs can be derived from both FLT3+ CMP and CLP (50, 51). Competitive in vivo transfer experiments with CMPs and CLPs showed that pDCs can also be generated from both, but are mainly of “myeloid” origin (52). Subsequent studies indicated that CMP and CLP-derived pDCs differ in their ability to produce type I IFN and to stimulate T cells (53, 54). Interestingly, a significant proportion of pDCs expresses recombination activation genes (Rag1/Rag2) and undergoes immunoglobulin DH-JH rearrangement indicating a “lymphoid” past. But the expression of Rag genes and detection of Ig rearrangements in pDCs derived from both CMP and CLP suggested that these are by-products of a “lymphoid” transcriptional program expressed only transiently in the pDC lineage (55, 56). However, the issue was revisited by Sathe et al. who found that RAG1 expression and Ig rearrangement are mainly found in CLP-derived pDCs (54). pDC generation from CLPs but not CDPs required constitutive type I IFN signals for upregulation of FLT3, suggesting differential requirements for instructive cytokines for the two developmental pathways (57). After the discovery that myeloid progenitor derived CDPs generate both cDCs and pDCs, research mostly focused on the branching of pDC and cDC development.

We found that CCR9low pDC-like precursor cells (CD11c+ Siglec H+ BST2+ B220lo/hi), which express lower levels of E2-2 and higher levels of Id2 than pDCs, can be generated from murine CDPs and these can give rise to CCR9high pDCs as well as cDCs [Figure 1, (11, 58, 59)]. The CCR9low pDC-like precursor population in the BM contains only a small fraction of proliferating cells indicating heterogeneity within this population regarding differentiation stage (58). It remains to be determined if this population, which can also be detected in lymphoid organs at low frequency contains differentiated cells with plasticity to develop into pDCs and cDCs or precursors with dual potential or both. Interestingly, pDC-like cells with a similar phenotype accumulated in the BM of Mtg16-deficient mice, which failed to downregulate Id2 expression, thereby blocking the activity of E2-2 and further pDC differentiation (60). In addition, Zeb2 has been identified as an important regulator of Id2 expression, which allows pDC development from CDPs by suppressing the alternative cDC1 fate at a common precursor stage (22, 23). More recently Etv6 was shown to cooperate with IRF8 to refine cDC1-specific gene expression and repress the pDC gene expression signature indicating the close relationship between cDC1 and pDCs (61). Siglec-H, a canonical marker distinguishing mature pDCs from cDCs, is expressed at very early stages of differentiation, but does not denote a plasmacytoid commitment. Within the CDP and the pre-DC fraction in the BM, Siglec-H+ cells expressing TF Zbtb46 are exclusively committed to cDCs (62) and were shown to contain precursors committed to cDC1 and cDC2 (13, 14). Similarly, Siglec-H+ Ly-6C+ cells in the pre-DC compartment (defined as Lin− CD135+ CD11c+ MHCII− CD172α−) were shown to give rise to both subsets of cDCs, whereas Siglec-H+ Ly-6C− pre-DCs gave rise to cDC subsets and pDCs (13). Using the single cell imaging and tracking method we could show that CDP progeny transit through a CD11c+ CCR9low Siglec-H+ pDC-like stage during their development into CCR9high pDCs (11). The CDP-derived pDC-committed precursor, which must be present within this population, is still a missing link. M-CSFR+ CDPs give rise to pDCs, however their output is rather low. Interestingly, Onai et al. found that the pDC potential was higher in the M-CSFR− E2-2+ fraction of CDPs in murine BM (12, 63). They also demonstrated that E2-2high cells within M-CSFR− IL-7R− CDPs gave rise exclusively to pDCs in spleen and lymph nodes, but also to cDCs in the small intestine, showing the plasticity of this pDC-primed CDP subset or its progeny in the local tissue environment (63).

More recently Rodrigues et al. found that FLT3+ IL-7R (CD127)+ CD117lo/int lymphoid progenitor (LP) cells in murine BM, which differ from CDPs only by expression of IL-7R and lack of M-CSFR expression, have a 5-fold higher output of pDCs compared to CDPs (15). Within this LP pool, three subpopulations were distinguished by diverse expression of Siglec-H and Ly-6D. Of these, only the Siglec-H Ly-6D double positive (DP) population had exclusive pDC potential, while the Ly-6D single positive (SP) population generated both B cells and pDCs, congruent with the results of a recently published computational fate mapping analysis of single cell RNAseq data (64). Further analysis showed the SP population to contain cells committed either to B cell or to pDC differentiation. The model proposed by Rodrigues et al. suggests that IL-7R+ Siglec-H and Ly-6D DN LPs proceed to upregulate Ly-6D (SP) and, under the influence of lineage defining TFs IRF8 and EBF1 induced by FLT3L and IL-7 respectively, proceed either to the pDC lineage or towards B cells (Figure 1). Interestingly, mice lacking Zeb2 in CD11c+ cells were shown to have a severe defect in pDC numbers, which was attributed to failed repression of Id2 leading to diversion of precursors to cDC1 (22, 23). Since a substantial proportion of pDCs was shown to be derived from the LP which lacks cDC potential in the steady state (65), it remains to be investigated if the transcriptional repressor Zeb2 is also involved in suppressing alternative cell fates in the LP.

Functionally, the IL-7R+ DP cells described by Rodriguez et al. as pDC precursors can be considered immature progenitors, as they do not yet express genes important for pDC function (such as Irf7 and Spib) and require further cell divisions to generate mature pDCs (15). In contrast to the CDP-derived CD11c+ Siglec-H+ CCR9low pDC-like precursors, the IL-7R+ DP cells lack CD11c and B220 expression and fail to produce type I IFNs in response to TLR9 stimulation by CpG-A, a hallmark of the pDC-lineage, but acquire this capacity after culture with FLT3L (15).

IL-7R+ Siglec-H+ Ly-6D+ pDC-committed precursors make a substantial contribution to the pool of differentiated pDCs. Thus, pDC generation seems to be regulated by the cell fate decision between pDC and cDC1, but also by the pDC versus B cell dichotomy. The contribution of the two pathways to pDC generation under conditions of inflammation or infection and the functional consequences of the distinct ontogeny of pDCs remain to be investigated.

Heterogeneity of pDCs and pDC-Like Cells in Murine Lymphoid Organs

Different subsets of pDCs have been identified in the BM, mostly differing in their degree of differentiation and their capacity to produce type I IFNs or pro-inflammatory cytokines (4, 66). Markers such as CCR9, SCA-1, CD9, and Ly-49Q, which are expressed by the majority of peripheral mouse pDCs, can be used to discriminate these subsets (59, 67, 68). More recently, single cell RNAseq analysis confirmed the presence of two subsets within Lin− CD11c+ BST2+ Siglec-H+ cells in spleen and BM (15). The “pDC-like cells” described in this paper express several genes characteristic of cDCs and other myeloid cells (including Zbtb46) but lack or express low levels of Ccr9, Ly6d, and Dntt. By gene expression profile and surface phenotype (lower levels of Siglec-H, BST2, MHCII, higher levels of CD11c, Ly-6C, and CX3CR1 compared to pDCs) they greatly resemble the CCR9low MHCIIlow CX3CR1+ pDC-like precursors described previously in BM (58, 59) and are a subset of those. Interestingly, Rodrigues et al. also found that the minor subset of pDC-like cells (defined as Zbtb46-eGFP+ Siglec-Hint BST2+), responded with IFN-α production to CpG-A and showed better antigen processing and presenting ability than “regular” pDCs. It was also previously shown that IFN-β production in the spleen is limited to a small subset of CD9− cells within the CCR9+ mature pDC population in murine spleen (69).

These works suggest the existence of minor subsets of pDCs in peripheral organs, differing in the extent of IFN-I production and the capacity of antigen processing and presentation. Considering that these subsets identified by differential expression of surface markers are largely overlapping and often very rare, it remains unclear whether the functional differences observed are due to functional specialization or are the result of lineage imprinting, or whether they are simply sequential stages of pDC differentiation leading to the mature pDC.

Revisiting the Definition of Human pDCs

The pDC-like cells described in the mouse which express pDC markers and TFs, but rapidly give rise to cDCs and behave like cDCs in antigen presentation assays greatly resemble the subset of CD123+ CD45RA+ CD33+ CX3CR1+ pre-DCs recently identified in human blood (35) and the AXL+ SIGLEC6+ human blood DC subset (AS-DC) described by Villani et al. (34). These “pDC-like cells,” which are hidden in the pDC population as defined by surface marker expression (Lin− HLA-DR+ CD123+ CD45RA+ CD303+), are functionally distinct from pDC in that they do not produce type I IFN in response to TLR7 and 9 stimulation. In that respect they are different from the Zbtb46+ Siglec-H+ pDC-like cells found in murine spleen. As to their classification as precursors of cDCs, it is based mainly on the observation that the pre-DCs acquire cDC phenotype and function in culture (35). The human pre-DC population contains pre-cDC1 and pre-cDC2 (35, 70). However, these cells are not proliferating in the steady state and appear to be functionally mature and could therefore actively participate in immune responses (34, 35). Cells in human blood, BM and tonsil defined as a CD2+ CD5+ (and CD81+) subpopulation of human pDCs were studied previously and were found to produce IL-12 but not IFN-α and to stimulate naïve CD4+ T cells (71–74). This population is largely overlapping with the recently described pre-DC and AS-DC (34, 35). It is currently not resolved to which extent cytokine responses and T cell activation capacity attributed to human pDCs in earlier studies were influenced by contamination by cDC precursors, especially because most studies were performed with pDCs that had been stimulated e.g., with IL-3, CD40L or viruses (75–77). It was shown recently that human blood pDCs diversify into functionally distinct and stable subsets after activation by influenza virus or CpG even after prior exclusion of contaminating pre-DCs demonstrating great functional plasticity of this cell type (78). In the light of these recent findings the functional properties of bona fide pDCs in innate and adaptive immune responses need to be reexamined.

Future Perspectives

Technological advances including single cell transcriptome, epigenome, and mass cytometry analyses as well as single cell tracking methods have revealed that development and functional specification of DC subpopulations is much more complex than anticipated. Several questions regarding pDC development and functional plasticity remain unanswered. It would be important to address the contribution of the CDP and LP to pDCs during infections or inflammation and to clarify if the developmental history of pDCs is really relevant for their function. Furthermore, it is unclear at this point, which functions ascribed to human pDCs are mediated by bona fide pDCs and which are mediated by the contaminating pre-DCs. This is especially important for developing pDC-targeted or adoptive transfer therapies for induction of immunity or tolerance. Similarly, the functional diversification of pDCs after activation and also the phenomenon of pDC exhaustion during chronic infection (79) are important topics for further study. An exciting area of research is the correlation of gene expression with chromatin accessibility and epigenetic modifications on the single cell level and the integration of all this data (80), which will allow to unravel the transcriptional regulation of cell fate decisions leading to pDC development and functional diversification. Combined with CRISPR/Cas9-based genetic screening and functional assays these new single cell analysis methods will lead to a thorough understanding of development, plasticity and function of DC subpopulations with implications for DC targeted therapy.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. AK received funding from the German Research Foundation (SFB 1054 TP A06 and TRR 237 TP B14) and Friedrich-Baur-Foundation.

References

Articles from Frontiers in Immunology are provided here courtesy of Frontiers Media SA

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01222

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01222/pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01222

Article citations

Chemical respiratory sensitization-Current status of mechanistic understanding, knowledge gaps and possible identification methods of sensitizers.

Front Toxicol, 6:1331803, 29 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39135743 | PMCID: PMC11317441

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Transcriptional programming mediated by the histone demethylase KDM5C regulates dendritic cell population heterogeneity and function.

Cell Rep, 43(8):114506, 24 Jul 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39052479 | PMCID: PMC11416765

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells at the forefront of anti-cancer immunity: rewiring strategies for tumor microenvironment remodeling.

J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 43(1):196, 17 Jul 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39020402 | PMCID: PMC11253500

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Dendritic Cells in Shaping Anti-Tumor T Cell Response.

Cancers (Basel), 16(12):2211, 13 Jun 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38927916

Review

Pathologic characteristics of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms.

Blood Res, 59(1):18, 07 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38713245 | PMCID: PMC11076448

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (65) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells develop from Ly6D+ lymphoid progenitors distinct from the myeloid lineage.

Nat Immunol, 20(7):852-864, 18 Jun 2019

Cited by: 108 articles | PMID: 31213723

The developmental program of human dendritic cells is operated independently of conventional myeloid and lymphoid pathways.

Blood, 110(10):3591-3660, 30 Jul 2007

Cited by: 66 articles | PMID: 17664352 | PMCID: PMC2077309

Efficient Generation of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell from Common Lymphoid Progenitors by Flt3 Ligand.

PLoS One, 10(8):e0135217, 11 Aug 2015

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 26263178 | PMCID: PMC4532451

Development of dendritic cell system.

Cell Mol Immunol, 1(2):112-118, 01 Apr 2004

Cited by: 35 articles | PMID: 16212897

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (1)

Grant ID: SFB 1054 TP A06