Abstract

Free full text

Notch signaling pathway: architecture, disease, and therapeutics

Abstract

The NOTCH gene was identified approximately 110 years ago. Classical studies have revealed that NOTCH signaling is an evolutionarily conserved pathway. NOTCH receptors undergo three cleavages and translocate into the nucleus to regulate the transcription of target genes. NOTCH signaling deeply participates in the development and homeostasis of multiple tissues and organs, the aberration of which results in cancerous and noncancerous diseases. However, recent studies indicate that the outcomes of NOTCH signaling are changeable and highly dependent on context. In terms of cancers, NOTCH signaling can both promote and inhibit tumor development in various types of cancer. The overall performance of NOTCH-targeted therapies in clinical trials has failed to meet expectations. Additionally, NOTCH mutation has been proposed as a predictive biomarker for immune checkpoint blockade therapy in many cancers. Collectively, the NOTCH pathway needs to be integrally assessed with new perspectives to inspire discoveries and applications. In this review, we focus on both classical and the latest findings related to NOTCH signaling to illustrate the history, architecture, regulatory mechanisms, contributions to physiological development, related diseases, and therapeutic applications of the NOTCH pathway. The contributions of NOTCH signaling to the tumor immune microenvironment and cancer immunotherapy are also highlighted. We hope this review will help not only beginners but also experts to systematically and thoroughly understand the NOTCH signaling pathway.

Introduction

The NOTCH gene was first named in studies of Drosophila melanogaster with notched wings in the 1910s1–3. Homologs of NOTCH were then identified in multiple metazoans, and all these NOTCH homologs shared similar structures and signaling components4–7. NOTCH variants were also found in ancient humans and were found to be involved in brain size control8. Generally, NOTCH is considered an ancient and highly conserved signaling pathway. NOTCH signaling participates in various biological processes across species, such as organ formation, tissue function, and tissue repair; thus, aberrant NOTCH signaling may cause pathological consequences.

In the past two decades, various drugs targeting NOTCH signaling have been tested in preclinical and clinical settings, yet no drug has been approved. Recent studies indicate that the NOTCH pathway is far more extensive and complicated than previously believed. As immunotherapy has revolutionized cancer treatment, NOTCH signaling and its relation with antitumor immunity have attracted the attention of scientists.

This review aims to illustrate the history, architecture, regulatory mechanisms, relation to health and diseases, and therapeutic applications of the NOTCH signaling pathway. In regard to specific behaviors of the NOTCH signaling pathway, we tried to focus on studies of mammals rather than those of other animals. We hope this review will help not only beginners but also experts to systematically and thoroughly understand the NOTCH signaling pathway.

A brief history of notch signaling

The NOTCH gene was first described in a study of D. melanogaster mutants with notched wings in the 1910s1,3,4. Haploinsufficiency of NOTCH caused D. melanogaster to have notches at the end of their wings, while complete insufficiency was lethal. The discovery of this phenotype inspired the later proposed nomenclature. The D. melanogaster NOTCH gene was then isolated9 and sequenced10 in the 1980s, and the putative NOTCH protein was found to span the membrane and contain many epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like repeats11. Studies of NOTCH signaling in D. melanogaster then increased12–18, drawing attention to the whole signaling pathway. In 1988 and 1989, LIN-12 and GLP-1 were identified as NOTCH homologs in Caenorhabditis elegans4,5, seemingly associated with C. elegans development5,19,20. In 1990, XOTCH (a homolog of D. melanogaster NOTCH) was identified in Xenopus6, and the cDNA of the mammalian NOTCH gene was cloned7. Since then, research on NOTCH in other animals has gained popularity. More details of NOTCH signaling have been clarified, and as such, NOTCH has been recognized as an ancient and highly conserved signaling pathway across metazoans21–26.

In 1991, the NOTCH gene was first linked to human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). In 1997, Alagille syndrome (AGS) was found to be caused by the mutation of JAG1, which encodes a ligand of NOTCH127,28. AGS is a noncancerous autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the abnormal development of multiple organs. Since these discoveries, the relationship of NOTCH with human health and diseases has been extensively studied. In addition, translational studies have been performed. The first clinical trial involving NOTCH signaling was launched in 2006, using a γ-secretase inhibitor to treat patients with T-ALL or other leukemias29,30. It was halted due to severe diarrhea, yet the results largely promoted the therapeutic targeting of NOTCH signaling. Various drugs and antibodies targeting other components of NOTCH signaling have been explored in preclinical and clinical settings, although none has yet been approved. In recent years, many new studies have been appearing, such as detailed structural analyses31–33, analyses of complicated regulatory mechanisms34,35, and analyses of diversified functions in health and diseases36–38, highlighting some unexplored areas of NOTCH signaling. A brief history of NOTCH signaling is shown in Fig. Fig.1.1. A strong understanding of NOTCH signaling is required; thus, more efforts are needed.

The architecture of notch signaling

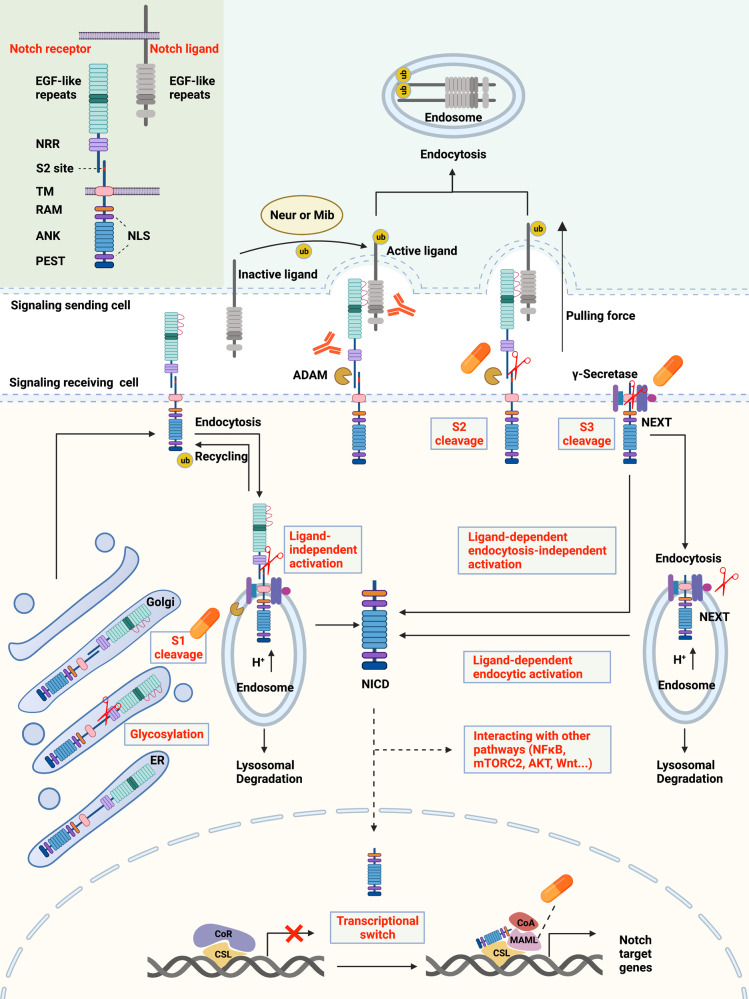

The NOTCH signaling pathway has certain characteristics. Classical signaling pathways, mediated by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)39 and enzyme-linked receptors40, have multiple intermediates between the membranous receptors and nuclear effectors. However, the canonical NOTCH signaling pathway has no intermediate, with receptors directly translocated into the nucleus after three cleavages21,41,42 (Fig. (Fig.2).2). In addition, S2 cleavage of NOTCH receptors is triggered by interactions with ligands expressed on adjacent cells, indicating a rather narrow range of NOTCH signaling. NOTCH signaling is involved in multiple aspects of metazoans’ life42, including cell fate decisions, embryo and tissue development, tissue functions and repair, as well as noncancerous and cancerous diseases. Thus, understanding of the architecture of the NOTCH signaling pathway is necessary.

Overview of the NOTCH signaling pathway and therapeutic targets. In signal-receiving cells, NOTCH receptors are first generated in the ER and then trafficked to the Golgi apparatus. During trafficking, NOTCH receptors are glycosylated at the EGF-like repeat domain (red curves). Then, in the Golgi apparatus, NOTCH receptors are cleaved into heterodimers (S1 cleavage) and transported to the cell membrane. With the help of ubiquitin ligases, some of the NOTCH receptors on the cell membrane are endocytosed into endosomes. Endosomes contain an acidic environment with ADAMs and γ-secretase. The NOTCH receptors in endosomes can be recycled to the cell membrane, cleaved into NICD, or transported into lysosomes for degradation. In signal-sending cells, NOTCH ligands are distributed on the cell membrane and can bind to NOTCH receptors on signal-receiving cells. However, the ligands are inactive before ubiquitylation by Neur or Mib. After ubiquitylation, ligands can be endocytosed, thus producing a pulling force for the binding receptors. Without the pulling force, the S2 site (red marks) of NOTCH receptors is hidden by the NRR domain, and thus, the NOTCH receptors are resistant to cleavage by ADAMs. With the pulling force, the NRR domain is extended, therefore exposing the S2 site for cleavage. ADAMs and the pulling force are both necessary for S2 cleavage. After S2 cleavage, the remaining part of the NOTCH receptor is called NEXT. NEXT can be further cleaved on the cell membrane by γ-secretase or endocytosed into endosomes. In the former mode, NICD is released on the cell membrane. In the latter mode, NEXT can be cleaved into NICD or transported into lysosomes for degradation. In total, there are three approaches to generate NICD, classified as ligand-independent activation, ligand-dependent endocytosis-independent activation, and ligand-dependent endocytic activation. NICD can be translocated into the nucleus or remain in the cytoplasm to crosstalk with other signaling pathways, such as NFκB, mTORC2, AKT, and Wnt. The classical model proposes that, in the absence of NICD, CSL binds with corepressors to inhibit the transcription of target genes. Once NICD enters the nucleus, it can bind with CSL and recruit MAMLs, releasing corepressors, recruiting coactivators, and thus promoting the transcription of NOTCH target genes. There are two main approaches to inhibit NOTCH signaling for therapy. One is designing inhibitors of the key components of the pathways, including the enzymes that participate in S1 cleavage, ADAMs, γ-secretase, and MAML. The other one is producing antibody-drug conjugates against NOTCH receptors and ligands. The protein structures of NOTCH ligands and receptors are shown in the top left corner. NICD, NOTCH intracellular domain; ADAM, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein; Neur, Neuralized; Mib, Mindbomb; NRR, negative regulatory region; NEXT, NOTCH extracellular truncation; CSL, CBF-1/suppressor of hairless/Lag1; MAMLs, Mastermind-like proteins; TM, transmembrane domain; RAM, RBPJ association module; ANK, ankyrin repeats; PEST, proline/glutamic acid/serine/threonine-rich motifs; NLS, nuclear localization sequence; CoR, corepressor; CoA, coactivator; ub, ubiquitin

The receptors and ligands of NOTCH signaling

D. melanogaster has only one NOTCH receptor9. C. elegans has two redundant NOTCH receptors, LIN-12 and GLP-14. Mammals have four NOTCH paralogs, NOTCH1, NOTCH2, NOTCH3, and NOTCH421, showing both redundant and unique functions. In humans, NOTCH1, NOTCH2, NOTCH3, and NOTCH4 are located on chromosomes 9, 1, 19, and 6, respectively. After transcription and translation, NOTCH precursors are generated in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and then translocated into the Golgi apparatus. In the ER, the NOTCH precursors are initially glycosylated at the EGF-like repeat domain. Glycosylations include O-fucosylation, O-glucosylation, and O-GlcNAcylation, which are catalyzed by the enzymes POFUT1, POGLUT1, and EOGT1, respectively43. Subsequently, in the Golgi apparatus, O-fucose is extended by the Fringe family of GlcNAc transferases, while O-glucose is extended by the xylosyltransferases GXYLT1/2 and XXYLT144–46. The glycosylation of NOTCH is vital to its stability and function. Alteration of core glycosylation enzymes severely inhibits the activity of NOTCH signaling47–51, making these enzymes vital for further research.

The glycosylated NOTCH precursors undergo S1 cleavage in the Golgi apparatus before being transported to the cell membrane. The cleavage always occurs at a conserved site (heterodimerization domain) and is catalyzed by a furin-like protease, cutting NOTCH into a heterodimer (mature form). Here, we take mouse NOTCH1 as an example to illustrate the structure of mature NOTCH on the cell membrane.

The extracellular domain (N-terminal) contains 36 EGF-like repeats and a negative regulatory region (NRR)43. The 11th and 12th EGF-like repeats usually interact with ligands43, although a new study found that many more motifs of the extracellular domain are involved in ligand binding52. The NRR domain is composed of three cysteine-rich Lin12-NOTCH repeats (LNRs) and a heterodimerization region critical for S2 cleavage. Located after the membrane-spanning region, the intracellular RBPJ association module (RAM) domain is responsible for interacting with transcription factors in the nucleus, and seven ankyrin repeat (ANK) domains are observed in the RAM domain. Nuclear localization sequences are located on both sides of the ANK domains. At the end of the intracellular domain (C-terminus), there are conserved proline/glutamic acid/serine/threonine-rich motifs (PEST domains) that contain degradation signals and are thus critical for the stability of the NOTCH intracellular domain (NICD). Mammalian NOTCH2-4 have similar structures to NOTCH1, diverging mainly in the number of EGF-like repeats, the glycosylation level of the EGF-like repeats, and the length of the PEST domains. The level of NOTCH receptors on the cell membrane is controlled by constitutive endocytosis, which is promoted by ubiquitin ligases. An appreciable amount of NOTCH receptors are ubiquitinated and degraded in the proteosome, while the rest are expressed on the cell membrane to transmit signals.

Humans and mice have five acknowledged NOTCH ligands21,53,54: delta-like ligand 1 (DLL1), delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3), delta-like ligand 4 (DLL4), Jagged-1 (JAG1), and Jagged-2 (JAG2), all of which present redundant and unique functions. For instance, DLL1 governs cell differentiation and cell-to-cell communication54, DLL3 suppresses cell growth by inducing apoptosis55, DLL4 activates NF-κΒ signaling to enhance vascular endothelial factor (VEGF) secretion and tumor metastasis56, JAG1 enhances angiogenesis54, and JAG2 promotes cell survival and proliferation54.

The structures of the NOTCH ligands are partially similar to those of the receptors. The ligands are also transmembrane proteins, and the extracellular domains contain multiple EGF-like repeats, which determine the crosstalk with corresponding receptors. The levels and functions of the ligands are also controlled by ubiquitylation and endocytosis (discussed in the section “Ligand ubiquitylation”).

The canonical NOTCH signaling pathway

The mature NOTCH receptors on the cell membrane are heterodimers, with the heterodimerization domain being cleaved in the Golgi apparatus (S1 cleavage). Generally, binding to extracellular domains of NOTCH receptors allows ligands to initiate endocytosis. Such endocytosis induces receptors to change their conformation, exposing the enzymatic site for S2 cleavage57. Receptors then experience S3 cleavage, changing into the effector form: NOTCH intracellular domain (NICD). NICD is degraded in the cytoplasm or transported into the nucleus to regulate the transcription of target genes (Fig. (Fig.22).

S2 cleavage is the only ligand-binding step and is thus vital for signal initiation. The structural basis of S2 cleavage is illustrated in Fig. Fig.2.2. The S2 site (metalloprotease site) is hidden by the LNR domain in the silent phase, referred to as the “autoinhibited conformation”58. Once bound with ligands, the receptor extends the LNR domain and exposes the S2 site for cleavage59–61. The core enzymes for S2 cleavage include a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM 10) and its isoforms ADAM 17 and ADAMTS162–64, which are popular targets for drug discovery. The product of S2 cleavage (larger part) is composed of the transmembrane domain and the intracellular domain, which is also called NOTCH extracellular truncation (NEXT)65.

NEXT is further cleaved at the S3 site, releasing NICD, which can be translocated into the nucleus and function as a transcription factor. The enzyme responsible for S3 cleavage is γ-secretase, which contains the catalytic subunits presenilin1 or presenilin2 (PS1 or PS2)66,67, APH-1, PEN-2, and nicastrin (NCT)68. However, the classical substrates for γ-secretase contain NOTCH receptors and amyloid precursor protein (APP), the successive cleavage of which is related to Alzheimer’s disease69–72. The structural basis for γ-secretase to recognize NOTCH or APP had remained unclear until recently, when Yigong Shi’s team elucidated the structural basis31,32. In short, the transmembrane helix of NOTCH or APP closely interacts with the surrounding transmembrane helix of PS1 (the catalytic subunit of γ-secretase); thus, the hybrid β-sheet promotes substrate cleavages, although some differences exist between NOTCH and APP73. Structural information would accelerate the discovery of substrate-specific inhibitors of NOTCH and APP. Additionally, S3 cleavage can occur both on the cell membrane and in the endosome after NEXT is endocytosed, termed the endocytosis-independent model and endocytic-activation model, respectively74.

After release from the cell membrane, NICD is translocated into the nucleus to regulate gene transcription, the mechanism of which may be related to the nuclear localization sequences of NICD and importins alpha 3, 4, and 775. However, the details of this translocation remain unclear. CBF-1/suppressor of hairless/Lag1 (CSL, also called recombination signal binding protein-J, RBPJ) is a ubiquitous transcription factor (TF) that recruits other co-TFs to regulate gene expression76,77. The target genes of NOTCH signaling are largely determined by the Su (H) motif of CSL, which is responsible for DNA binding21. The canonical NOTCH target gene families are Hairy/Enhancer of Split (HES) and Hairy/Enhancer of Split related to YRPW motif (HEY)21.

In the traditional model of NICD regulating gene transcription21,42,78,79, CSL recruits corepressor proteins and histone deacetylases (HDACs) to repress the transcription of target genes without NICD binding. NICD binding can change the conformation of the CSL-repressing complex, dissociating repressive proteins and recruiting activating partners to promote the transcription of target genes. The transcriptional coactivator Mastermind-like protein (MAML) is one of the core activating partners that can recognize the NICD/CSL interface, after which it recruits other activating partners. Drugs targeting MAML are under study.

Recently, Kimble et al. used single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization to study the NOTCH transcriptional program in germline stem cells of C. elegans and found that NICD dictated the probability of transcriptional firing and thus the number of nascent transcripts80. However, NICD did not orchestrate a synchronous transcriptional response in the nucleus, in contrast to that seen in the classical model. Gomez-Lamarca et al. found similar results in D. melanogaster81. NICD promoted the opening of chromatin and enhanced the recruitment of both the NICD-containing activating CSL complex and the NICD-free repressive CSL complex. Bray et al. proposed a new model to interpret their findings. In the NOTCH-off state, chromatin is compact, and only the NICD-free (repressing) CSL complex regulates transcription. In the NOTCH-on state, chromatin is loosened and bound to both NICD-containing (activating) and NICD-free (repressive) CSL complexes. Because the number of activating complexes is greater than that of repressive complexes after NICD enters the nucleus, NICD promotes the transcription of target genes. Bray et al. further reported that nucleosome turnover occurred frequently at NOTCH-responsive regions and depended on the Brahma SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex82. Consistently, Kimble et al. found that NOTCH signaling regulated the duration of the transcriptional burst but not the intensity of signaling or the time between bursts83. Oncogenic NOTCH is also considered to enhance repositioning to promote the transcription of genes, such as MYC84. In general, the new model from Bray et al. helps explain the flexibility of NOTCH signaling, although the details still require further elucidation.

The noncanonical NOTCH signaling pathway

Pathways other than canonical signaling pathway are also able to initiate signaling, classified as noncanonical NOTCH signaling pathways. Although the mature NOTCH receptors on the cell membrane are capable of ligand binding, some are endocytosed for renewal. Endocytosed NOTCH receptors can return to the cell membrane, be degraded in lysosomes or activated in endosomes (ligand-independent activation)74,85. Interestingly, endosome trafficking can also be regulated by NOTCH signaling86. Endosomes have been proven to contain ADAM and γ-secretase87. Ligand-independent activation of NOTCH signaling is vital to T cell development88. One example of ligand-independent activation is T cell receptor (TCR)-mediated self-amplification87. The activated TCR/CD3 complex can activate the signaling axis of LCK-ZAP70-PLCγ-PKC. PKC then activates ADAM and γ-secretase on the endosome to initiate S2 and S3 cleavage and thus NOTCH signaling. Activated NOTCH signaling can further upregulate immune-related genes to amplify the immune response.

Independent of CSL, NICD can interact with the NF-κB, mTORC, PTEN, AKT, Wnt, Hippo, or TGF-β pathways at the cytoplasmic and/or nuclear level to regulate the transcription of target genes34,89–96. The crosstalk between NICD and NF-κB affects the malignant properties of cervical cancer89, colorectal cancer97, breast cancer98, and small-cell lung cancer cells99. Targeting the NF-κB pathway could be an effective way to block noncanonical NOTCH signaling.

In addition to those mentioned above, there is a newly identified mechanism of noncanonical activation. In the classical model, S3 cleavage is necessary for NOTCH receptors to release NICD and thus regulate the transcription of target genes. However, membrane-tethered NOTCH may activate the PI3K-AKT pathway, promoting the transcription of interleukin-10 and interleukin-12100. In blood flow-mediated NOTCH signaling, the transmembrane domain instead of NICD recruits other partners to promote the formation of an endothelial barrier35. NOTCH3 itself can promote the apoptosis of tumor endothelial cells, independent of cleavage and transcription regulation101. The JAG1 intracellular domain can promote tumor growth and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) without binding to NOTCH receptors102. These noncanonical mechanisms provide this ancient signaling pathway with more unique functions while massively increasing its complexity.

The mechanisms regulating NOTCH signaling

Glycosylation

The glycosylation of NOTCH receptors on specific EGF-like repeats is crucial for the maturation of receptors, which also affects signaling output. First, O-fucosylation catalyzes the enzyme Pofut1 to affect ligand binding. Elimination of Pofut1 greatly influences the ligand binding of NOTCH signaling in embryonic stem cells, lymphoid cells, and angiogenic cells of mice103–105. The aberration of fringe family proteins, which catalyzes the elongation of O-fucose, can also affect ligand binding106–109. Second, O-glucose of NOTCH receptors is involved in S2 cleavage. Alteration of O-glucosylation damages the proteolysis of NOTCH receptors after ligand binding110,111. Third, the sites of O-glycosylation, such as EGF 12, are important regions for ligand binding, the loss of which decreases NOTCH signaling in T cells112. Furthermore, EGF 28 might contribute to DLL1-mediated NOTCH1 signaling113. Targeting glycosylation is also thought to effectively inhibit NOTCH signaling114.

Receptor trafficking

After S1 cleavage, most mature NOTCH proteins are transported to the cell membrane. However, reaching the membrane does not guarantee stability. NOTCH receptors are constitutively endocytosed through a process modulated by ubiquitin ligases such as FBXW, NUMB, ASB, DTX1, NEDD4, ITCH, and CBL74,115–118. Endocytosed NOTCH can be recycled to the cell membrane or trapped in the cytoplasm74; thus, receptor trafficking can directly affect the level of NOTCH receptors on the cell membrane. Furthermore, the endocytosed NOTCH receptors in the cytoplasm can be degraded or activated. Degradation is usually initiated by the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) system119–122, the failure of which also lays the foundation for receptor activation. However, the mechanism of ligand-independent activation remains clear123–125. The balance between degradation and activation after endocytosis is closely related to downstream signaling79. The specific distribution of receptors and ligands on the cell membrane can also influence the regional intensity of NOTCH signaling79.

Ligand ubiquitylation

Unlike the ubiquitylation of NOTCH receptors, ubiquitylation of ligands (usually catalyzed by Neuralized (Neur) and Mindbomb (Mib)) in signal-sending cells is necessary for signaling activation. Without Neur or Mib, NOTCH signaling decreases significantly126–128. One explanation is that the endocytosis of ligands promotes exposure of the NRR domain of the receptor for S2 cleavage129,130.

Cis-inhibition

Receptors and ligands expressed on different cells can initiate signal transduction. However, receptors and ligands expressed on the same cell both inhibit and activate the whole signaling pathway, termed cis-inhibition and cis-activation79,131. DLL3 seems to operate only in cis-inhibition132,133. The loss of DLL3 increases NOTCH activity during T cell development in vivo133. DLL1-NOTCH1 can function in both cis- and trans-activation131. Thus, the balance between cis- and trans-interactions can be vital to signaling output.

Other regulatory mechanisms

Various signals regulate the transcription of NOTCH receptors and thus the whole signaling pathway, such as AKT, RUNX1, SIRT6, CBFB, and DEC1134–138. Many noncoding RNAs regulate the level of NOTCH receptors, such as microRNA-26a, microRNA-26b, microRNA-153, microRNA-182, and microRNA-34a139–142. Nitric oxide regulates the activity of ADAM17 and USP9X and ultimately NOTCH signaling143,144. Calzado et al. found that dual-specificity tyrosine-regulated kinase 2 (DYRK2) phosphorylated the NOTCH1 intracellular domain to promote its degradation by FBXW7145. In the classical model, NOTCH signaling is prompted through the interaction between receptors and ligands in extracellular domains. However Suckling et al. found that the interaction between the C2 domain of NOTCH ligands and the phospholipid membrane of receptor-containing cells modulated NOTCH signaling.146 This finding provides a possible explanation for the diversified consequences of NOTCH signaling mediated by different ligand–receptor interactions.

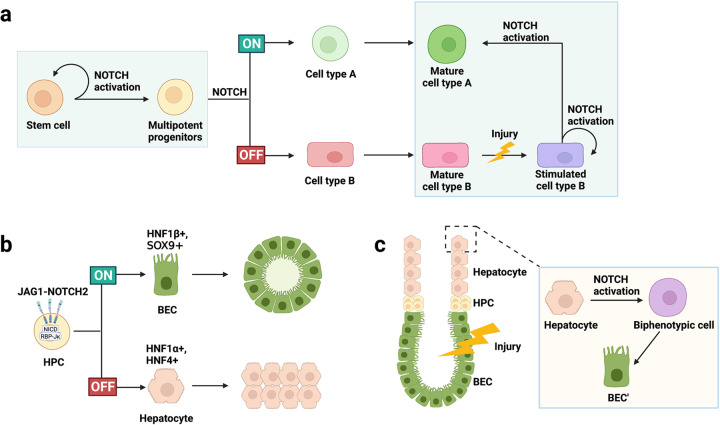

Notch signaling in organ development and repair

As a highly conserved signaling pathway, NOTCH deficiency leads to serious embryonic lethality. NOTCH signaling is active in the early stage of embryonic development but is maintained at a low level in the mature stage of body development. It also increases rapidly under conditions of injury or stress and is indispensable for development and injury repair (Fig. (Fig.3).3). First, NOTCH signaling promotes the self-renewal and dedifferentiation of stem and progenitor cells, thus maintains progenitor stemness and the stem cell pool. Among these cells, neural stem cells147–149 and multipotent progenitor cells (MPCs)150,151 are classic representatives. Different combinations of NOTCH ligands and receptors promote stem cell proliferation and inhibit terminal differentiation. Second, NOTCH signaling is involved in the selection of cell fate. Based on temporal and spatial expression of NOTCH ligands, receptors, and cell-enriched transcription factors, NOTCH signaling induces fixed differentiation of progenitor cells, such as differentiation of cardiac progenitor cells into endocardial cells and hepatoblasts into bile duct lineage cells152,153. Furthermore, NOTCH signaling is vital to maintaining the homeostasis of the body in normal regeneration and damage repair. NOTCH signaling can rapidly regulate the dynamic transformation of cells to maintain physiological homeostasis, such as stem cells and tail cells in angiogenesis, through lateral inhibition154–157. It also induces the differentiation and transformation of mature cells to promote damage repair, for example, in liver regeneration158. Last, numerous ligands and receptors are involved in NOTCH signaling and have specified temporal and spatial expression in various organs and tissues, although the consequences are similar.

The role of NOTCH signaling in body development and damage repair. NOTCH signaling is involved in regulating the differentiation and function of stem cells, affecting organ production and damage repair. a NOTCH signaling promotes the self-renewal of stem cells, induces multipotent progenitors for lineage selection, and generates different terminal cells; when the organ is damaged, cell type A is damaged and destroyed, and the stimulated cell type B rapidly upregulates the expression of NOTCH signaling to promote their own proliferation, and is partially redifferentiated into cell type A. b Highly activated NOTCH induces the expression of bile duct cell-enriched transcription factors and promotes the differentiation of multipotent hepatocyte progenitors into bile duct epithelial cells. c In liver injury, BEC are damaged and destroyed. NOTCH signaling is highly expressed in hepatocytes, which are further transformed into biphenotypic cells, which manifests the biliary tract morphology, and finally generate new BEC (BEC’) to form small tubular structures. HPC, hematopoietic progenitor cell; BEC, bile duct epithelial cell; SOX9, SRY-related high-mobility group box 9; HNF, hepatocyte nuclear factor

NOTCH and somitogenesis

The somitogenesis of vertebrates occurs in a strict order and is regulated by the segmentation clock. It is closely related to the expression of oscillating genes regulated by NOTCH, Wnt and FGF signaling159–162. NOTCH signaling triggers an excitatory signal, causing presomitic mesoderm (PSM) to transition into a self-sustaining cyclic oscillation state163,164. The gene oscillation period is consistent with the half-life of HES7165 and induces lunatic fringe (Lfng) transcription. LFNG, as a glycosyl transferase that can modify the extracellular domain of NOTCH after translation and periodically blocks the cleavage of NOTCH receptors, causes the formation of cyclic NICD166–168. PSM is a group of self-sustaining oscillating cells, but the synchronous oscillation between depends on the transmission of NOTCH signaling169–171. LFNG inhibits the activation of NOTCH signaling in neighboring cells by regulating the function of DLL1164,172,173. In Lfng-knockout mice, PMS oscillation fails to synchronize, but PMS oscillation amplitude and period remain unaffected170. This finding further demonstrates that LFNG is a key coupling factor for synchronous oscillations between cells.

NOTCH and skeleton

In the growth and development of MPC, NOTCH signaling regulates and inhibits the production of osteoblasts151, chondrocytes174–178, and osteoclasts179,180 through different ligands and receptors (NOTCH1, NOTCH2, JAG1, DLL1) as well as the downstream target gene (SRY-related high-mobility group box 9, SOX9). In addition, the latest research shows that inhibiting glucose metabolism can guide NOTCH to regulate MPC150, proving the complex role of NOTCH signaling in the skeletal microenvironment. In the mouse model, the absence of NOTCH signaling leads to depletion of MPC and nonunion of fractures181, consistent with the finding that activated JAG1-NOTCH signaling reduces MPC senescence and cell cycle arrest. Interestingly, using γ-secretase inhibitors intermittently and temporarily for fractures significantly promotes cartilage and bone callus formation, as well as superior strength182. This indicates that NOTCH signaling exerts its function in a temporally and spatially dependent manner.

NOTCH and cardiomyogenesis

During heart wall formation, NOTCH signaling regulates the ratio of cardiomyocytes to noncardiomyocytes by inhibiting myogenesis, further promoting atrioventricular canal remodeling and maturation, EMT development and heart valve formation183–185. In the endocardium layer, the DLL4-NOTCH1-mediated Hey1/2-Bmp2-Tbx2 signaling axis is a complex negative feedback regulation loop, where overexpressed Tbx2 can in turn inhibit upstream Hey expression186–189. In embryos lacking key NOTCH signaling molecules such as Notch1, Rbpj, Hey1/Heyl, or Hey2, EMT development is hindered, and endocardial cells are activated but fail to scatter and invade heart glia190. NOTCH signaling affects the expression of the cadherin 5190 and the TGF-β family member bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2)186,189. In addition, by downregulating VEGFR2, a key negative regulator of EMT within atrioventricular canals (AVCs), NOTCH signaling further induces EMT. Studies have found that active NOTCH1 is most highly expressed in endocardial cells at the base of the trabecular membrane. Bone morphogenetic protein 10 (BMP10)191 and Neuregulin 1 (NRG1)192 are key molecules of NOTCH signaling that regulate the proliferation, differentiation, and correct folding of cardiomyocytes during trabecular development.

NOTCH and the vasculature

NOTCH4 and DLL4 are specifically expressed on vascular endothelial cells (ECs)184,193. Deficiencies in NOTCH signaling result in serious defects in the vasculature of the embryo and yolk sac during embryonic development194 as well as abnormal development of multiple organs, such as the retinal vasculature195,196 and uterine blood vessels197 in rats. At the cellular level, the vascular system mainly includes ECs, pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). Under stressors such as hypoxia, resting ECs quickly transform into a state of active growth and high plasticity and then dynamically transform between tip cells (TCs) and stalk cells (SCs) through lateral inhibition rather than direct lineage changes154,155. This cascade reaction between DLL4-mediated NOTCH signaling and VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling induces ECs near dominant TCs to maintain a high level of NOTCH signaling, inhibiting their differentiation into TCs198,199. NOTCH signaling activates the Wnt pathway through feedback regulation to maintain the connection between ECs, promoting vascular stability200. In addition, DLL4-NOTCH can maintain arterial blood–retinal barrier homeostasis by inhibiting transcytosis201. NOTCH signaling is also important for the development of VSMCs202,203. Blocking Notch signaling in neural crest cells, especially NOTCH2 and NOTCH3, results in vascular dysplasia, aortic defects, and even bleeding202,204–206. The regulation of the downstream transcription factors PAX1, SCX, and SOX9 by NOTCH signaling is vital for regulating the differentiation of progenitor cells in the sclera toward VSMCs207.

NOTCH signaling acts decisively in the arteriovenous differentiation of endothelial cells208,209. NOTCH signaling induces the expression of the arterial marker ephrin B2 and inhibits that of the venous marker EphB4, thereby regulating the number and diameter of arteriovenous vessels210,211. In mice with dysfunctional mutations of NOTCH signaling molecules such as Notch1, Dll4, Hey1, or Hey2, the arterial subregion is defective, while venous differentiation is hyperactive, leading to unexpected bleeding210,212,213. Before blood perfusion, active NOTCH signaling on the arterial side can be detected. High levels of VEGF, ERK/MAP kinase and Wnt pathway components increase DLL4 expression214,215, and the transcription factors Fox1C and Fox2C promote DLL4 activation216. Interestingly, ECs can sense and respond to laminar flow through NOTCH1, similar to the shear stress response, transforming the hemodynamic mechanical force into an intracellular signal, which is necessary for vascular balance217,218.

NOTCH and the hemopoietic system

NOTCH signaling is important in the differentiation, development, and function of hematopoietic system cells, both lymphocytes and myeloid cells. In early embryonic development, the hematopoietic endothelium forms hematopoietic stem cells through NOTCH-dependent endothelial-to-hematopoietic transition219. NOTCH signaling is fundamental in maintaining the number and stemness of hematopoietic stem cells220. In lymphocyte development, the absence of NOTCH1 or CSL in early hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) leads to thymic T cell development retardation and B cell accumulation, with HES1 being the key mediator221. Naïve thymocytes highly express NOTCH and immediately downregulate NOTCH1 expression once they successfully pass β-selection. Some scholars propose that NOTCH-mediated T cell development is initiated in the prethymic niche222,223. For example, bone mesenchymal cells outside the thymus can cross-link with HPCs through NOTCH ligands on the surface to promote the generation of T cell lineages224,225. Shreya S et al. induced the production of HSPC-derived CD7+ progenitor T cells with DLL4 and VCAM-1 in vitro engineering, and these cells further differentiated into mature T cells after thymus transplantation226. Regarding B cells, the development of splenic marginal zone B (MZB) cells depends on DLL1-NOTCH2 signaling227,228. In addition, it was found that active NOTCH2 signaling can mediate the lineage conversion of follicular B cells into MZB cells so that mature B cell subpopulations can quickly and dynamically transform based on the needs of the immune system229,230. The development of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) was recently found to be NOTCH-dependent231–233, and the response of different subtypes of ILCs to NOTCH signaling is heterogeneous234,235. It is interesting that ILCs can activate MZB cells through DLL1 to enhance antibody production236. Regarding myeloid cells, NOTCH signaling is significant in the development of macrophages237,238, dendritic cells239,240, granulocytes241, etc.

NOTCH and the liver

NOTCH signaling plays a key role in determining the fate of biliary tract cells and directing the correct morphogenesis of the biliary tree. Active NOTCH signaling, especially mediated by NOTCH2 and JAG1, promotes the expression of transcription factors enriched in bile duct cells, induces the differentiation of hepatocytes toward bile duct cells, and promotes the formation of the bile duct plates152,153. The expression of SOX9, a downstream molecule of NOTCH signaling, is synchronized with the asymmetric development of the bile duct152,242, with a mouse model of liver-specific deletion of Sox9 echoing this finding. Interestingly, delayed biliary tract development caused by liver-specific deletion of Sox9 eventually resolves in a spontaneous manner, proving that SOX9 plays a major role in timing regulation through the development of the biliary tract243.

The liver has a strong compensatory regeneration ability, where NOTCH signaling responds quickly with significant upregulation, and the transformation of hepatocytes into bile duct-like cells can be observed (Fig. (Fig.3c).3c). Similarly, high levels of dual-phenotype hepatocytes can also be observed in liver slices of patients with early liver diseases. Additionally, in a mouse orthotopic liver transplantation model, a high level of NOTCH1 (NICD and HES1) signaling was found to have a protective effect on hepatocytes during ischemia–reperfusion injury, regulating macrophage immunity244. In incomplete liver injury, NOTCH signaling mediates the proliferation and differentiation of facultative progenitor cells, thereby promoting biliary tract repair. Such damage repair can be induced mainly by NOTCH2245,246, consistent with the discovery of the role of NOTCH2 signaling in the differentiation and selection of liver progenitor cells during liver development.

NOTCH and the gastrointestinal tract

Studies have shown that NOTCH signaling prevents embryonic epithelial cells from differentiating into secretory lineages247, with Hes1 being the main negative regulator248. Highly activated NOTCH signaling promotes the differentiation of intestinal stem cells toward intestinal epithelial cells249. Inhibiting NOTCH signaling increases the differentiation of secretory goblet cells250. Additionally, the lateral inhibition of NOTCH/DLL1 and the synergy of the Wnt signaling pathway250 drive Paneth cell differentiation and subsequent crypt formation251. NOTCH signaling is also essential in the lineage selection of gastric stem cells252 and necessary to maintain the homeostasis of gastric antral stem cells253. Activated NOTCH signaling in differentiated mature gastric epithelial cells induces their dedifferentiation254. NOTCH signaling is also vital to the proliferation of pancreatic progenitor cells and their correct differentiation into mature pancreatic cells255,256. DLL1 and DLL4 are specifically expressed in β cells, while JAG1 is expressed in α cells257. The DLL1-NOTCH-HES1 signaling axis promotes the growth and fate selection of multipotent pancreatic progenitor cells, while JAG1 competes with DLL1 to induce opposite effects258.

NOTCH and the nervous system

NOTCH signaling negatively regulates neurogenic phenotypes259–262. Its absence induces differentiation of neural stem cells toward neurons at the cost of glial cell production, in both D. melanogaster and vertebrates263–266. There are two mainstream models: the classic lateral inhibition model that is similar to vascular development267 and the model involving oscillatory expression of HES1, NEUROG2 and DLL1268. In addition, NOTCH signaling promotes the differentiation of most glial cell subtypes, except for oligodendrocytes. In the peripheral nervous system, the interaction between NOTCH signaling and Hairy2 is vital for the development of neural crest cells, although the specific regulatory mechanism remains unclear269. Active NOTCH signaling blocks the occurrence and stratification of the trigeminal nerve, leading to disorders of brain development. Furthermore, NOTCH signaling drives intestinal neural crest cells to develop into precocious glial cells in Hirschsprung disease270,271. These results indicate that NOTCH signaling participates in neural crest differentiation, but further exploration is required272.

NOTCH and other organs or systems

NOTCH signaling functions throughout lung development and the damage repair process273. Components of NOTCH signaling are highly expressed in various cells and tissues during lung development. Inhibition of NOTCH signaling or RBPJ deficiency causes defects in proximal airway differentiation, club-cell secretion inhibition, and excessive proliferation of ciliated cells and neuroendocrine cells. NOTCH2 is the main factor activating alveolar morphogenesis and maintaining airway epithelial integrity274. NOTCH signaling mediates the balance between the proliferation and differentiation of basal cells275. In damage repair, NOTCH2 in basal cells is activated, promoting the separation of cell lineages and producing secretory cells276.

NOTCH signaling is important in cell lineage selection, epidermal homeostasis and skin function277. NOTCH signaling in the skin promotes cell differentiation278, while NOTCH in hair follicles inhibits cell differentiation, promotes proliferation and maintains stemness. Notch signaling is also closely related to cilia cell proliferation, differentiation and morphogenesis and may be involved in asymmetric cell division in the embryonic epidermis279,280. NOTCH signaling regulates sebaceous gland stem cells directly and indirectly. In Rbpj-deficient mice, the differentiation of sebaceous stem cells is inhibited, and the number of sebaceous glands (SGs) is reduced, with compensatory, enlarged SGs still existing281. Many skin diseases have been found to have NOTCH signaling changes, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis282,283.

Notch signaling in noncancerous diseases

As mentioned above, NOTCH signaling is essential for body development and homeostasis, indicating that NOTCH signaling is vital for the occurrence and development of diseases. Most genetic diseases caused by NOTCH mutations have a low incidence and lack effective treatment. For example, the first discovered related disorder, Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), has no effective treatment other than supportive treatment. The prognosis of only a few patients with AGS can be improved through liver transplantation, suggesting that further research is necessary. Most of the diseases caused by nonmutant NOTCH signaling abnormalities present corresponding developmental characteristics. New and interesting findings have appeared recently. For example, NOTCH signaling may be related to alcohol-associated preference, playing an important role in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. We will now focus on the manifestations of NOTCH signaling abnormalities in diseases caused by congenital or nongenetic mutations (Table (Table11).

Table 1

NOTCH Signaling in Noncancerous diseases

| Disease type | Key NOTCH components | Affected organs/tissue | Main manifestations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases related to abnormal expression of NOTCH signaling factors caused by gene mutation | ||||

| CADASIL | NOTCH3 | Arterioles of the brain | Particulate osmophilic substances are deposited near VSMCs; arterial damage and brain damage | 285,286,291,636 |

| Alagille syndrome | NOTCH2, JAG1 | Multiple organs and systems | Absence of bile ducts, cholestasis; peripheral arterial stenosis; specific facial features | 28,293,301 |

| Spondylocostal dysostosis | DLL3, MESP2, HES7 | Vertebral column | Malformed ribs, asymmetrical rib cage, short trunk | 306,637 |

| Hajdu-Cheney disease | NOTCH2 | Skeletal tissue | Truncated NOTCH2 proteins escape ubiquitylation and degradation, mediating active NOTCH2 signaling; osteoporosis, craniofacial anomalies | 638–640 |

| Left ventricle cardiomyopathy | MIB1 | Heart | Promotes the engulfment of NOTCH ligands, inhibits NOTCH signal transduction; hinders ventricular myocardium development | 641,642 |

| Adams-Oliver syndrome | NOTCH1, RBPJ, DLL4 | Skin, limbs | Scalp hypoplasia, terminal transverse limb defects | 643,644 |

| Bicuspid aortic valve disease | NOTCH1, RBPJ, JAG1 | Cardiac valves | Related to valvular disorders of EMT and valve calcification | 645–647 |

| Schizophrenia | NOTCH4 | Brain | One of the strongest candidate susceptibility genes for schizophrenia | 648,649 |

| Diseases related to abnormal expression of NOTCH signaling factors caused by factors other than gene mutation | ||||

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | NOTCH1, NOTCH3 | Pulmonary vasculature | ECs and VSMCs hyperproliferation and activation; vascular remodeling, pulmonary artery obstruction | 331,332,650,651 |

| Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | NOTCH1, JAG1 | Liver | Abnormal NOTCH signaling activation in liver cells promotes osteopontin expression and secretion | 315,316,318 |

| Osteoarthritis | RBPJ, JAG1, HES1 | Articular cartilage | Abnormally high expression of NOTCH factors in OA; NOTCH signaling plays a dual regulatory role, participating in both damage repair and progression of disease, with temporal and spatial specificity | 320–323 |

| Graft versus host disease | NOTCH1, NOTCH2, JAG1, DLL1, DLL4 | Immune system | Activation and promotion the differentiation and function of T cells; increases the BCR responsiveness of patient B cells | 337,339,340,652 |

| Pancreatitis | NOTCH1, JAG1, HES1 | Pancreas | Associated with tissue regeneration and renewal after pancreatitis; contributes to the differentiation and proliferation of acinar cells | 653–655 |

| Multiple sclerosis | JAG1 | Myelin sheath | Inhibition of oligodendrocyte maturation and differentiation and formation of the myelin sheath | 656–658 |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | JAG1 | Skeletal muscle | Associated with the depletion and senescence of MPCs | 659,660 |

| Klippel-Feil syndrome | RIPPLY2 | Vertebra | Regulates the asymmetric development of embryos | 661,662 |

| Alcohol associative preference | NOTCH/Su(H) | Neurons | Affects alcohol-related neuroplasticity in adults | 663 |

CADASIL Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, VSMCs vascular smooth muscle cells, MESP2 mesoderm posterior 2, MIB1 mindbomb homolog 1, RBPJ recombination signal binding protein-J, EMT epithelial–mesenchymal transition, ECs endothelial cells, OA osteoarthritis, BCR B-cell receptor, MPCs multipotent progenitor cells, RIPPLY2 ripply transcriptional repressor 2, Su(H) suppressor of hairless

Diseases associated with abnormal expression of NOTCH signaling related to mutations

CADASIL

CADASIL syndrome, an arteriolar vascular disease mediated by dominant mutations in the NOTCH3 gene, is the most common hereditary cause of stroke and vascular dementia in adults284,285. NOTCH3 is mainly expressed in VSMCs and pericytes, especially arterioles. In a study of 50 unrelated CADASIL patients, 45 with NOTCH3 pathogenic mutations286 presented abnormal folding of NOTCH3 and deposition of osmophilic particles near VSMCs287,288, and cerebral arteries showed reduced lumen diameter unassociated with chronic hypertension289. Notch3-knockout mice show obvious structural abnormalities of arterioles and loss of vascular smooth muscle, simulating some CADASIL vascular changes, but are insufficient to constitute a complete CADASIL pathological model290. Attempts have been made to simulate the main pathological features of CADASIL regarding vascular damage and unique brain damage291, such as introducing Notch3 pathogenic point mutations into large P1-derived artificial chromosomes (PACs) to construct transgenic mouse models with large genome fragments of Nothc3 pathogenic mutations292 and using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cell modeling. Evidently, NOTCH3 is pathogenic when mutated, although its underlying mechanism remains unclear.

Alagille syndrome

AGS is an autosomal dominant genetic disease caused by abnormal NOTCH signaling, with JAG1 mutations being predominant (greater than 90%) and NOTCH2 mutations being second most common (5%)27,28,293. AGS affects multiple organs throughout the body, inducing, for example, abnormal development of the liver, heart, vasculature, bones, eyes, and maxillofacial dysplasia. Liver damage is the most prominent and is characterized by a lack of interlobular bile ducts and varying degrees of cholestasis, jaundice, and itching. AGS is one of the most important causes of chronic cholestasis in children. Symptoms ameliorate with age, yet there is still no effective treatment other than liver transplantation294,295. These findings are consistent with the roles of JAG1 and NOTCH2 in bile duct development and morphological maintenance mentioned above. Interestingly, according to statistics, JAG1 has more than 430 mutation sites outside of mutation hotspots. Similarly, its phenotype is highly variable, and a correlation between genotype and phenotype has not yet been found296–299. Thus, it remains a mystery how changes in different NOTCH receptors and ligands affect the occurrence and development of AGS. There was no research model with the characteristics of AGS until the structural defect model of the biliary tree using biopsies from AGS patients was developed, and experiments have indicated that AGS liver organoids may be a good human 3D model of AGS300. JAG1 homozygous mutations often lead to embryonic lethality in mice. Andersson et al. successfully constructed mice homozygous for a missense mutation (H268Q) in Jag1 (Jag1Ndr/Ndr), and these mice showed a decreased rate of embryonic lethality and recapitulation of all AGS features. Surviving mice presented with the classic absence of bile ducts and other features of AGS, including defects of the heart, vasculature, and eyes301,302. In the pathological tissues of patients and mouse models, Joshua et al. found that the expression level of SOX9 was negatively correlated with the severity of AGS liver damage, and overexpression of SOX9 could rescue bile duct loss in Jag1+/– mouse models. One explanation is that overexpressed SOX9 can be recruited to the NOTCH2 promoter to upregulate the expression of NOTCH2 in the liver, thereby compensating for the decreased expression of the JAG1 ligand303. These new research models and related experimental data have promoted and informed further research on AGS.

Congenital scoliosis

Sporadic and familial congenital scoliosis (CS) refers to the lateral curvature of at least one spine segment caused by fetal spinal dysplasia. Studies have shown that CS is closely related to genetic factors, environmental factors, developmental abnormalities, and NOTCH signaling304. Several key NOTCH genes involved in the segmentation clock mechanism may explain the features of a genetic model of a rare syndrome characterized mainly by CS-spondylocostal dysostosis (SCD)305,306.

When analyzing genes in the families of SCD patients, multiple mutation sites in DLL3 are found, and the phenotype of pyramidal dysplasia in Dll3-free mice is similar to that of SCD patients307. The genetic correlation between DLL3 mutation and spinal rib dysplasia has been reported308, and DLL3 deletion alone is unable to induce a complete SCD phenotype. In addition, Mesp2 is a downstream gene of NOTCH in somite differentiation, and abnormal expression of its 4 pairs of base repeats are closely related to SCD. Mesp2-knockout mice have spinal chondrodysplasia and serve as the current main research model309,310. In mice, inactivation of Lfng or Hes7 can distort the development of the spine and ribs, with corresponding mutations also found in patients311,312. Furthermore, environmental damage to genetically susceptible mice affects the penetrance and severity of the CS phenotype, especially under hypoxic conditions, providing an explanation for the family phenotypic variation of SCD313.

Diseases associated with abnormal expression of NOTCH signaling not related to mutations

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

There is almost no NOTCH activity in hepatocytes of healthy adults, while NOTCH activity is slightly elevated in hepatocytes of people with simple steatosis and highly elevated in the hepatocytes of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)/fibrosis patients; NOTCH activity is positively correlated with the severity of the disease. In NASH patients or high-fat diet-induced NASH mouse models, the expression of NOTCH1, NOTCH2, and HES1 is highly elevated, which activates neoadipogenesis and increases liver steatosis314–316. Such abnormal NOTCH activation may mainly be induced by JAG1/NOTCH signaling triggered by intercellular TLR4317. NOTCH-active hepatocytes can upregulate the expression of SPP1 through the downstream transcription factor SOX9, promoting secretion of osteopontin (OPN) by hepatocytes and activating hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) to induce liver fibrosis318.

Osteoarthritis

The expression level of NOTCH signaling components is low in the articular cartilage of healthy adults but higher in osteoarthritis (OA) biopsies319,320. After trauma, NOTCH signaling is abnormally activated in joint tissues, and its continuous activation can cause early and progressive OA-like lesions. However, transient NOTCH signaling activation helps synthesize cartilage matrix and promotes joint repair321. Inhibition of NOTCH signaling was found to significantly reduce the proliferation of OA chondrocytes. However, the specific inhibition of cartilage NOTCH signaling and the decrease in MMP13 abundance in the joint can delay cartilage degeneration322. Eventually, long-term loss of NOTCH signaling will cause cartilage homeostasis imbalance and bone destruction. The findings above suggest that Rbpj and Hes1 play a major mediating role323. In summary, NOTCH signaling presents duality when regulating the physiology and pathology of articular cartilage, and its effects are depending on temporal and spatial factors.

Lung-related diseases

Allergic asthma is mainly driven by the Th2 immune response, where NOTCH signaling activates the expression of the key transcription factor Gata3324,325. Preclinical studies of γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI) have also proven that inhibiting NOTCH signaling reduces the asthma phenotype326,327. NOTCH signaling plays an important role in promoting Th2 cell lymph node regression and lung migration328. NOTCH4 has been further proven to be vital in the occurrence of asthma. Repeated exposure to allergens can induce regulatory T cells (Tregs) to upregulate the expression of NOTCH4, dampening their immunoregulatory function and activating downstream Wnt and Hippo pathways. These factors turn Tregs into Th2 and Th17 cells, maintaining persistent allergic asthma95,329. In addition, upregulation of JAG1 expression is found in lung tissues of patients with interstitial pulmonary fibrosis. In chronic lung injury, repeated injury promotes continuous upregulation of JAG1 by inhibiting CXCR7, leading to the continuous activation of NOTCH in surrounding fibroblasts and inducing profibrotic responses330. NOTCH3 is an important mediator of pulmonary artery remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) that mediates the excessive proliferation and dedifferentiation of VSMCs329. In addition, the regulation of NOTCH1 in endothelial cells also promotes the progression of PAH331,332. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common lung disease associated with smoking. Studies have shown that smoking and PM2.5 exposure promote the activation of NOTCH signaling, leading to the imbalance of T cell subsets and immune disorders, thus aggravating COPD333–335.

Other diseases

NOTCH signaling is a regulator of the CD4+ T cells that cause graft versus host disease (GVHD)336. Inhibition of NOTCH signaling reduces target organ injury and germinal center formation, significantly reducing the severity and mortality of GVHD337,338. Activated NOTCH signaling can directly activate reactive T cells and promote their function339. The responsiveness of patients’ B cell receptors is also significantly enhanced by activated NOTCH signaling340. NOTCH signaling is also involved in regulating the glomerular filtration barrier. Abnormal activation of NOTCH1 signaling in the glomerular endothelium inhibits the expression of VE-cadherin and induces albuminuria through the transcription factors Snai1 and Erg36. In adult pancreatic β cells, the abnormal activation of NOTCH signaling, especially DLL1 and DLL4, can promote β cell proliferation. A large number of naïve, dysfunctional β-cells, which proliferate but are unable to secrete insulin normally, causes glucose intolerance257,341.

Notch signaling in cancers

NOTCH as an oncogene in cancers

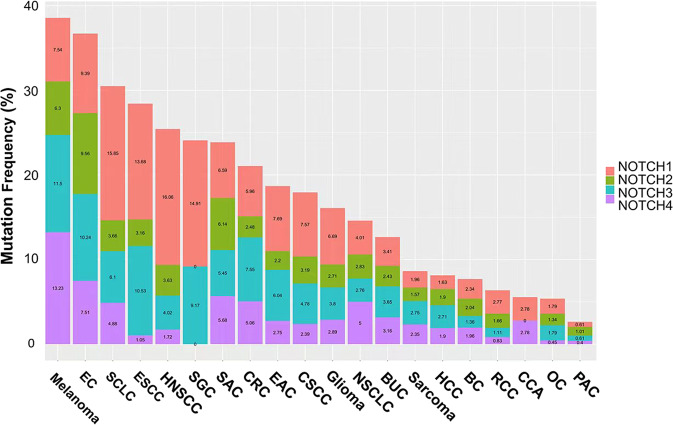

NOTCH was first identified as an oncogene in T-ALL342,343. Subsequently, the alteration of NOTCH receptors was discovered in various cancers (Fig. (Fig.4).4). The activation of NOTCH in breast cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular cancer, ovarian cancer and colorectal cancer was determined to be oncogenic78 (Table (Table2).2). The pattern of NOTCH activation varies; for example, NOTCH can be activated by upstream signals or by structural alteration resulting from its internal mutations. Potential mechanisms of tumorigenesis include controlling the tumor-initiating cell phenotype, regulating known upstream or downstream tumor-associated signaling factors, such as MYC or P53, facilitating angiogenesis or tumor invasion, regulating the cell cycle, etc. These mechanisms will now be discussed based on cancer type.

Mutation frequencies of NOTCH receptors in different cancers. Data are obtained from cBioPortal (http://cbioportal.org). We included data from two studies: MSK-IMPACT Clinical Sequencing and TCGA PanCancer Atlas Studies, with a total of 21289 patients. And we only used samples with mutation information, including missense, truncating, inframe, splice, and structural variation/fusion. This figure shows the mutation frequency of the four receptors of NOTCH in different cancer types. EC, endometrial carcinoma; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer; ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; HNSCC, head, and neck squamous cell carcinoma; SGC, salivary gland cancer; SAC, stomach adenocarcinoma; CRC, colorectal cancer; EAC, esophagogastric adenocarcinoma; CSCC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; BUC, bladder urothelial carcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; BC, breast cancer; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; OC, ovarian cancer; PAC, prostate adenocarcinoma

Table 2

NOTCH Signaling in Cancers

| Cancer type | Involved NOTCH components | Relevant evidence | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| NOTCH signaling pathway plays an oncogenic role | |||

| T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia | NOTCH1, NOTCH3 | More than 50% of T-ALL patients have NOTCH1 somatic activating mutations; Transplanted hematopoietic progenitor cells with activation of Notch1 signaling in murine models can develop T-ALL; Activating mutations of NOTCH3 without NOTCH1 has also been found in several T-ALLs. | 344,345,350 |

| Splenic marginal zone lymphoma | NOTCH1, NOTCH2 | Activating mutations of NOTCH signaling appeared in 58% of SMZLs, related to inferior survival. | 351 |

| B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia | NOTCH1-2, JAG1-2 | Constitutively expression of NOTCH1, NOTCH2 proteins and their ligands JAG1 and JAG2 were detected in B-CLL; Dysfunction of NOTCH signaling reduces the morbidity of B-CLL, while activation of NOTCH signaling increases its survival. | 352,664 |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | NOTCH1, NOTCH3 | NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 were detected highly expressed, suggesting poor prognosis and intensive invasion; Notch1-3 were confirmed contributing to the initiation and progression of LUAD in vivo and in vitro. | 355,356,358 |

| Breast cancer | NOTCH1, NOTCH4, JAG1 | Upregulation of non-mutated NOTCH1 and JAG1 is associated with poor prognosis of BC; The mutations of Notch1 and Notch4 mediated by the mouse mammary tumor virus can promote epithelial mammary tumorigenesis; BC cell lines with functionally recurrent rearrangements of NOTCH genes are sensitive to NOTCH inhibitors. | 379,380,382 |

| Colorectal cancer | NOTCH1 | Upregulation of NOTCH ligands (DLL1, DLL3, DLL4, JAG1 and JAG2) and aberrant activation of NOTCH1 were detected; Active Notch1 signaling induces the proliferation and activation of colon cancer hepatocytes, promoting cell invasion and metastasis. | 365,367 |

| Ovarian cancer | NOTCH1, NOTCH3 | Ntch1 and Notch3 promote the occurrence and development of ovarian cancer; Overexpression of Notch3 is related to cell hyperproliferation and anti-apoptosis. | 389–393 |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | NOTCH1-2 | Activated mutations of NOTCH1 and NOTCH2 were frequently detected in ACC; NOTCH1 inhibitors have significant antitumor efficacy in both ACC patients and PDX models. | 415–420 |

| Clear cell renal cell carcinoma | NOTCH1 | Overexpression of NOTCH ligands and receptors were observed in CCRCC tissues, and activated NOTCH1 led to dysplastic hyperproliferation of tubular epithelial cells. | 422 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma* | NOTCH1 | Approximately 30% of human HCC samples have activated NOTCH signaling, promoting the formation of liver tumors in mice; NOTCH activation facilitates EMT progression and metastasis in HCC; Mutations in the NOTCH target gene HES5 in HCC samples can present both protumorigenic and antitumorigenic functions. | 400,402,404 |

| Glioma* | NOTCH1-2 | Inhibiting NOTCH signaling with a γ-secretase inhibitor in glioma constrains tumor growth both in vivo and in vitro. NOTCH1 has oncogenic potential in the brain associating other oncogenic hotspots, such as p53 loss. Positive feedback of NOTCH1-SOX2 enhances glioma stem cell invasion along white matter tracts. Inactivation of Rbpj, Notch1 or Notch2 accelerates tumor growth in a mouse model. | 407–410 |

| NOTCH signaling pathway palys a tumor suppressing role | |||

| Squamous cell cancers | NOTCH1-3 | Inactivated NOTCH1-3 were detected in SCC specimens; The genomic aberrations in NOTCH1 induced by mutagenic agent could cause an increasing tumor burden in SCCs; DNMAML1, an inhibitor to canonical NOTCH transcription, promotes de novo SCC formation. | 438–440,449,451 |

| Neuroendocrine tumors | NOTCH1, DLL3 | Nearly 25% of human SCLC cases present inactivation of NOTCH target genes; DLL3, an inhibitory NOTCH signaling components, was detected highly expressed in SCLC and lung carcinoid tumors; Gastroenteropancreatic and lung neuroendocrine tumors exhibit decreased NOTCH expression and mutated NOTCH components; Activating NOTCH1 could inhibit the growth of thyroid neuroendocrine cancer cells in vitro. | 425,426,431,432 |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomaa | NOTCH1 | Notch1 could inhibit the formation of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia in a PDAC mouse model; Notch1 loss is required for progression in a Kras-induced PDAC model. | 454–456 |

T-ALL T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, SMZL splenic marginal zone lymphoma, B-CLL B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, LUAD lung adenocarcinoma, BC breast cancer, ACC adenoid cystic carcinoma, PDX patient-derived xenograft; CCRCC clear cell renal cell carcinoma, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, EMT epithelial–mesenchymal transition, SCC, squamous cell cancer; SCLC small-cell lung cancer, DANMAML1 Dominant-Negative Mastermind Like1, PDAC pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

aNOTCH might act as a tumor suppressor in oncogenic-oriented HCC405 and GBM413, while as an oncogene in tumorsuppressive-oriented PDAC454–456

Hematological malignancies

The oncogenic effects of NOTCH were first identified with the chromosome t (7;9) translocation of the NOTCH1 gene in T-ALL342,343. More than 50% of T-ALL patients have NOTCH1 somatic activating mutations344. Transplanted hematopoietic progenitor cells with constitutive activation of NOTCH1 signaling in murine models can lead to the development of T-ALL345. Mechanistically, NOTCH1 activation in T-ALL might involve the extracellular heterodimerization domain (HD) and/or the C-terminal PEST domain344. Mutations destabilizing the HD of NOTCH1 could facilitate ligand-independent pathway activation. Furthermore, mutations disrupting the intracellular PEST domain could increase the half-life of NICD1. Many studies suggest that NOTCH1 may induce the expression of MYC by regulating its enhancer N-Me and play a key role in the initiation and maintenance of T-ALL346. The interaction of NOTCH1 and PTEN promotes anabolic pathways in T-ALL347. In addition to these synergistic effects, NOTCH1 can directly regulate the expression of specific lncRNAs, such as LUNAR1, which is essential for the malignant proliferation of T-ALL cells348. Additionally, NOTCH signaling regulates the progression of the T-ALL cell cycle via the expression of the G(1) phase proteins cyclin D3, CDK4, and CDK6349. In recent years, activating mutations of NOTCH3 independent of NOTCH1 mutations have also been found in several cases350, providing novel insights into NOTCH mutations in T-ALL.

In addition, activating mutations in NOTCH have been identified in other hematological malignancies. Approximately 58% of splenic marginal zone lymphoma cases have activating NOTCH mutations, termed NNK-SMZLs, and such cases are related to inferior survival351. In a B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) murine model, dysfunction of NOTCH signaling reduces morbidity, while activation of NOTCH signaling increases the survival and apoptosis resistance of B-CLL cells352. In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), NOTCH also participates in the tumor growth through the FBXW7-NOTCH-CCL2/CSF1 axis353. Although NOTCH plays an oncogenic role in most hematological malignancies, it inhibits the growth and survival of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and consistent activation of NOTCH1-4 leads to AML growth arrest and caspase-dependent apoptosis354.

Lung adenocarcinoma

In lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) patients, high expression of NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 has been detected355,356. This alteration involves loss of NUMB expression, which increases NOTCH activity, and gain-of-function mutations of the NOTCH1 gene357. In vivo and in vitro studies confirmed that NOTCH1-3 contributes to the initiation and progression of LUAD358–360, indicating that NOTCH acts as an oncogene in LUAD. The tumorigenesis effect might involve activating mutations of downstream genes regulating the tumor-initiating cell phenotype. First, NOTCH3 is a key driver gene in KRAS-mediated LUAD that activates PKCι-ELF3-NOTCH3 signaling to regulate asymmetric cell division in tumor initiation and maintenance processes361. Second, coactivation of NOTCH1 and MYC increases the frequency of NICD1-induced adenoma formation and enables tumor progression and metastases in a mouse model360. In addition, NOTCH1 activation in KRAS-induced LUAD suppresses p53-mediated apoptosis358. However, NOTCH mutations have opposite effects in LUAD and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) according to recent studies362. Since most studies of NOTCH are conducted in undistinguished non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, the specific effect of NOTCH in LUAD needs further research.

Colorectal cancer

Physiologically, NOTCH signaling is essential for the development and homeostasis of normal intestinal epithelia; for example, NOTCH signaling regulates the differentiation of colonic goblet cells and stem cells363,364. In human colorectal cancer (CRC) tissues, significant upregulation of NOTCH ligands (DLL1, DLL3, DLL4, JAG1, and JAG2) and aberrant activation of the NOTCH receptor (NOTCH1) are found365,366. Such abnormal NOTCH activation is associated with poorer prognosis and metastasis of CRC367. Inhibiting NOTCH by miR-34a and Numb suppresses the proliferation and differentiation of colon cancer stem cells368, indicating that NOTCH activation is a trigger of colon cancer development. Abnormal NOTCH signaling promotes the invasion and metastasis of CRC cells, possibly through the NOTCH-DAB1-ABL-TRIO pathway, EMT and TGF-β-dependent neutrophil effects369. On the one hand, NOTCH promotes CRC invasion by inducing ABL tyrosine kinase activation and phosphorylation of the RHOGEF protein TRIO370. On the other hand, active NOTCH signaling promotes the occurrence of metastasis by reshaping the tumor microenvironment and regulating EMT-associated transcription factors such as SLUG and SNAIL367,371,372. In conclusion, the NOTCH pathway induces EMT in colon cancer with TP53 deletion370,373,374.

Breast cancer

Studies of NOTCH signaling in epithelial tumors were first performed in breast cancer375–378. Upregulation of non-mutated NOTCH signaling-related proteins, such as NOTCH1 and JAG1, is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer379. In mouse models, mutations in Notch1 and Notch4 mediated by mouse mammary tumor viruses can promote epithelial mammary tumorigenesis380,381. Moreover, functionally recurrent rearrangements of NOTCH gene families are found in breast cancer, of which cell lines are sensitive to NOTCH inhibitors382. In HER2-expressing breast cancer cells, NOTCH activation seems to be associated with cytotoxic chemotherapy resistance383. Such an abnormal increase in NOTCH signaling expression is believed to be related to a lack of NUMB expression384, and its promoting effect on breast cancer tumorigenesis might be exerted from multiple aspects. First, NOTCH signaling maintains the stemness of breast cancer cells and promotes initiation385,386. Second, NOTCH signaling shapes elements of the breast cancer microenvironment, especially tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which is related to the innate immune phenotype387. In addition, NOTCH can be activated by the ASPH-Notch axis, providing materials for the synthesis/release of prometastatic exosomes in breast cancer388.

Ovarian cancer

In ovarian cancer, approximately 23% of patients have NOTCH signaling alterations389. NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 have been discovered to directly promote the occurrence and development of ovarian cancer389–392. Overexpression of NOTCH3 is related to cell hyperproliferation and apoptosis inhibition, as well as tumor metastasis and recurrence393,394. As NOTCH3 is positively correlated with JAG1 and JAG2 expression in ovarian cancer, the carcinogenic function of NOTCH3 is potentially mediated by JAG1-NOTCH3 activation395, and dynamin-dependent endocytosis is required. Notch2/Notch3 and other NOTCH signaling molecules have achieved certain effects by inhibiting Jag1 in a mouse ovarian cancer model396,397. In addition, through methylation of the VEGFR2 promoter, NOTCH signaling facilitates angiogenesis in ovarian cancer mediated by VEGFR2 negative feedback398.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

NOTCH signaling is a pathogenic factor in NASH, yet its role in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is less well defined399. Approximately 30% of human HCC samples have activated NOTCH signaling, which in mice promotes the formation of liver tumors400. Recently, NOTCH activation was found in some HCC subtypes with unique molecular and clinicopathologic features and was found to be associated with poor prognosis399. NOTCH activation is also related to the activation of insulin-like growth factor 2, which contributes to hepatocarcinogenesis401. Furthermore, NOTCH activation facilitates EMT progression and metastasis in HCC402. On the other hand, NOTCH activation slows HCC growth and can predict HCC patient prognosis403. Mutations in the NOTCH target gene HES5 in HCC samples can present both protumorigenic and antitumorigenic functions404. A close relationship between the function of NOTCH1 and the P53 mutation state has been reported, in which NOTCH1 activation increases the invasiveness of P53 WT HCC cells while decreasing that of P53-mutated HCC cells405. Although showing contradictory functions in HCC, NOTCH is still mainly considered an oncogenic factor.

Glioma

NOTCH signaling used to be considered oncogenic in glioma, in which it maintains brain cancer stem cells406. Knockdown of NOTCH ligands in human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMECs) or inhibition of NOTCH signaling with a γ-secretase inhibitor in glioma constrains tumor growth both in vitro and in vivo407,408. Notch1 has potentially oncogenic effects in the brain in association with other oncogenic hits, such as p53 loss in a medulloblastoma mouse model409. Positive feedback of NOTCH1-SOX2 enhances glioma stem cell invasion along white matter tracts410. NOTCH also induces the expression of lncRNA and TUG1 to maintain the stemness of glioma stem cells and suppress differentiation411. Moreover, NOTCH1 signaling promotes the invasion and growth of glioma-initiating cells by modulating the CXCL12/CXCR4 chemokine system412. However, NOTCH suppresses forebrain tumor subtypes. Inactivation of Rbpj, Notch1, or Notch2 receptors accelerates tumor growth in a mouse model413. Such a subtype-specific effect of NOTCH in glioma might be related to cooperation with P53. Overall, NOTCH signaling acts either as an oncogenic factor or a tumor suppressor in different glioma subtypes, and the mechanisms need further exploration414.

Other cancers

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC), commonly found in the salivary gland, frequently features activating NOTCH1 and NOTCH2 mutations415–418. NOTCH1 inhibitors have significant antitumor efficacy in both ACC patients and patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models419,420. Upregulation of MYB signaling through NOTCH mutation and amplification might also be a potential driving mechanism of ACC421. Activated NOTCH1 also produces CD133(+) ACC cells, regarded as cancer stem-like cells in ACC. In clear cell renal cell carcinoma (CCRCC), the overexpression of NOTCH ligands and receptors is observed in tumor tissues. Activated NOTCH1 leads to dysplastic hyperproliferation of tubular epithelial cells, and treatment involving a γ-secretase inhibitor leads to CCRCC cell inhibition both in vitro and in vivo422.

NOTCH as a tumor suppressor in cancers

NOTCH may be involved in many cancers as a protumor effector, but it can also act as a tumor suppressor in others, such as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and neuroendocrine tumors423 (Fig. (Fig.4,4, Table Table2).2). Antitumor mechanisms include regulating transcription factors with malignant effects, activating downstream suppressive genes, inhibiting the cell cycle, etc. In light of studies regarding its antitumor effects, the traditional opinion of NOTCH as an oncogene has been challenged414.

Neuroendocrine tumors

NOTCH is now believed to act as a suppressor in neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), including tumors derived from the thyroid, neuroendocrine cells of the gut, the pancreas, and the respiratory system424. Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most common type of pulmonary NET, with nearly 25% of human SCLC cases presenting inactivation of NOTCH target genes in one comprehensive genomic profiling analysis425. A recent study used a multiomics approach to analyze the dynamic changes during transdifferentiation from NSCLC to SCLC426, which is a special feature of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs in LUAD. This study found that the downregulation of NOTCH signaling was essential for the initial cell state switch of LUAD cells426, indicating that NOTCH plays a tumor-suppressive role in SCLC. Furthermore, high DLL3 expression is frequently detected in SCLC and lung carcinoid tumors55,426–428, which downregulates NOTCH signaling via cis-inhibition. In an SCLC mouse model, activation of Notch1 or Notch2 reduces the expression of synaptophysin and Ascl1, inhibiting the cell cycle process429,430. Likewise, in human medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) tumor samples, NOTCH1 protein is undetectable, while the expression of NICD1 inhibits MTC cell proliferation431. In an analysis of gastroenteropancreatic NET tumor specimens, reduced NOTCH expression and mutated components were found432,433. Mechanistically, some studies consider that such an antitumorigenesis effect might be mediated by the NOTCH-ASCL1-RB-P53 tumor suppression pathway434,435, while others hold that activated NOTCH could inhibit cell growth via cell cycle arrest associated with upregulated P21431,436. NOTCH could also mark and initiate deprogramming in rare pulmonary NET cells that serve as stem cells in SCLC437. Considering the suppressor effect of NOTCH in NETs, drugs targeting DLL3 have been tested in SCLC, with promising results witnessed in preclinical trials (discussed in detail in the following sections).

Squamous cell cancers