Abstract

Background

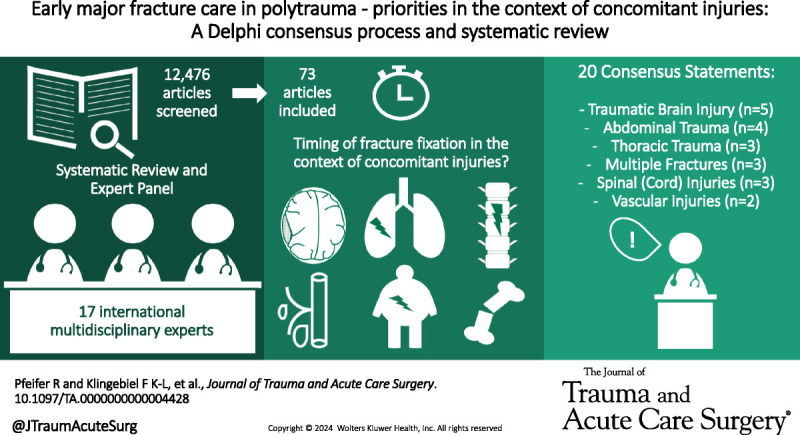

The timing of major fracture care in polytrauma patients has a relevant impact on outcomes. Yet, standardized treatment strategies with respect to concomitant injuries are rare. This study aims to provide expert recommendations regarding the timing of major fracture care in the presence of concomitant injuries to the brain, thorax, abdomen, spine/spinal cord, and vasculature, as well as multiple fractures.Methods

This study used the Delphi method supported by a systematic review. The review was conducted in the Medline and EMBASE databases to identify relevant literature on the timing of fracture care for patients with the aforementioned injury patterns. Then, consensus statements were developed by 17 international multidisciplinary experts based on the available evidence. The statements underwent repeated adjustments in online- and in-person meetings and were finally voted on. An agreement of ≥75% was set as the threshold for consensus. The level of evidence of the identified publications was rated using the GRADE approach.Results

A total of 12,476 publications were identified, and 73 were included. The majority of publications recommended early surgery (47/73). The threshold for early surgery was set within 24 hours in 45 publications. The expert panel developed 20 consensus statements and consensus >90% was achieved for all, with 15 reaching 100%. These statements define conditions and exceptions for early definitive fracture care in the presence of traumatic brain injury (n = 5), abdominal trauma (n = 4), thoracic trauma (n = 3), multiple extremity fractures (n = 3), spinal (cord) injuries (n = 3), and vascular injuries (n = 2).Conclusion

A total of 20 statements were developed on the timing of fracture fixation in patients with associated injuries. All statements agree that major fracture care should be initiated within 24 hours of admission and completed within that timeframe unless the clinical status or severe associated issues prevent the patient from going to the operating room.Level of evidence

Systematic Review/Meta-Analysis; Level IV.Free full text

Early major fracture care in polytrauma—priorities in the context of concomitant injuries: A Delphi consensus process and systematic review

Zurich, Switzerland

Abstract

BACKGROUND

The timing of major fracture care in polytrauma patients has a relevant impact on outcomes. Yet, standardized treatment strategies with respect to concomitant injuries are rare. This study aims to provide expert recommendations regarding the timing of major fracture care in the presence of concomitant injuries to the brain, thorax, abdomen, spine/spinal cord, and vasculature, as well as multiple fractures.

METHODS

This study used the Delphi method supported by a systematic review. The review was conducted in the Medline and EMBASE databases to identify relevant literature on the timing of fracture care for patients with the aforementioned injury patterns. Then, consensus statements were developed by 17 international multidisciplinary experts based on the available evidence. The statements underwent repeated adjustments in online- and in-person meetings and were finally voted on. An agreement of ≥75% was set as the threshold for consensus. The level of evidence of the identified publications was rated using the GRADE approach.

RESULTS

A total of 12,476 publications were identified, and 73 were included. The majority of publications recommended early surgery (47/73). The threshold for early surgery was set within 24 hours in 45 publications. The expert panel developed 20 consensus statements and consensus >90% was achieved for all, with 15 reaching 100%. These statements define conditions and exceptions for early definitive fracture care in the presence of traumatic brain injury (n = 5), abdominal trauma (n = 4), thoracic trauma (n = 3), multiple extremity fractures (n = 3), spinal (cord) injuries (n = 3), and vascular injuries (n = 2).

CONCLUSION

A total of 20 statements were developed on the timing of fracture fixation in patients with associated injuries. All statements agree that major fracture care should be initiated within 24 hours of admission and completed within that timeframe unless the clinical status or severe associated issues prevent the patient from going to the operating room.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE

Systematic Review/Meta-Analysis; Level IV.

Timing of major fracture care in polytrauma patients constitutes one of the central questions in trauma research and several study groups have focused on identifying risk factors for adverse outcomes concerning timing and the extent of surgical procedures.1–4 Among the major determinants are alterations of clinical and physiological parameters and the time until their normalization.5,6 Various algorithms have been proposed to clear these patients for early fracture care based on their physiological stability. In addition, injury pattern and the severity of concomitant injuries play a crucial role in delaying early definitive fracture care.7

While several studies examine the effects of specific injury patterns on the timing of fracture care, the number of evidence-based treatment recommendations is low, and sometimes outdated.

Therefore, the International MultidisciPlinAry Consensus Panel on PolyTrauma (IMPACT) group was established to create universally acceptable and applicable recommendations for the timing of fracture care in polytrauma patients.

The main focus of these recommendations is the specific role of concomitant injuries to the brain, thorax, abdomen, spine/spinal cord, and vasculature, as well as the role of multiple fractures.

METHODS

To create treatment recommendations for the timing of major fracture fixation in polytrauma patients with concomitant injuries, two scientific approaches were used and combined:

A Delphi consensus process conducted by a group of international experts

A systematic review of the literature

Delphi Consensus Process

The Delphi method was used according to recommended modifications.8 The consensus-based Checklist for Reporting Of Survey Studies (CROSS) was used (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/TA/D907).

Composition of the Consensus Group

A group of experts was selected by the scientific organizing committee according to the following criteria:

Knowledge about the topic

Previous publications and communications about the topic

Representation of all disciplines involved in the decision-making of fracture care (general trauma, orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery)

Global (geographic) representation

Representation of multiple trauma systems

Answer to the inquiries and the communications requested by the organizers (R.Pf. and H.-C.P.)

The detailed composition of the scientific organizing committee and the expert panel, along with their specialization and the country in which they practice, are presented in Table Table1.1. While the scientific organizing committee members created the initial statements, they were also part of the expert panel and participated in the voting process.

TABLE 1

List of International Experts, Participating in the Consensus Process

| Name | Specialty | Country | Continent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z. Balogh | Traumatology/Orthopedics | Australia | Australia |

| F. Beeres | Traumatology/Orthopedics | Switzerland | Europe |

| R. Coimbra | Traumatology | United States | North America |

| C. Fang | Traumatology/Orthopedics | China | Asia |

| P. Giannoudis | Traumatology/Orthopedics | United Kingdom | Europe |

| F. Hietbrink | Traumatology | Netherlands | Europe |

| F. Hildebrand | Traumatology/Orthopedics | Germany | Europe |

| H. Kurihara | Traumatology | Italy | Europe |

| T. Lustenberger | Traumatology/Orthopedics | Switzerland | Europe |

| I. Marzi | Traumatology/Orthopedics | Germany | Europe |

| M. Oertel | Neurosurgery | Switzerland | Europe |

| HC. Pape | Traumatology/Orthopedics | Switzerland | Europe |

| R. Pfeifer | Traumatology/Orthopedics | Switzerland | Europe |

| R. Peralta | Traumatology | Qatar | Asia |

| S. Rajasekaran | Traumatology/Orthopedics | India | Asia |

| E. Schemitsch | Orthopedics/Traumatology | Canada | North America |

| H. Vallier | Orthopedics/Traumatology | United States | North America |

| B. Zelle | Orthopedics/Traumatology | United States | North America |

Timeline

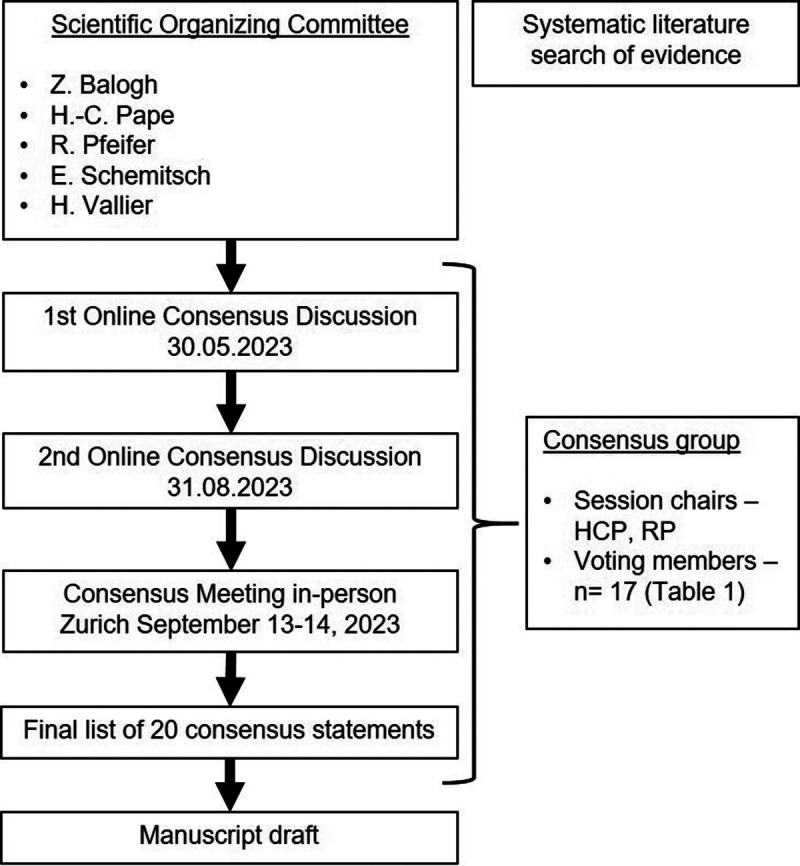

A timeline of the entire consensus process is provided in Figure Figure1.1. The scientific organizing committee (Z.J.B., H.-C.P., R.Pf., E.H.S., H.A.V.) initiated the process in May 2023, and a preamble was formulated (Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/TA/D910). The first consensus discussion took part online on May 30, 2023. A second online meeting was held on August 31, 2023. A final meeting was held in person on September 13–14, 2023. Subsequently, the formulated consensus statement was circulated among the group members for final confirmation.

Generation of Consensus Statements

In preparation for the meeting, the organizing committee summarized the findings of the systematic literature search, which were arranged into 12 initial statements and circulated among the IMPACT group members. Statements were then adjusted based on the experts' feedback and additional statements were formulated. This process was repeated twice. The adjusted statements were then discussed and finalized during the in-person consensus meeting.

Consensus Meeting

A 2-day in-person meeting was held on September 13–14, 2023, at the University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland. The consensus statements were adjusted through critical discussion with the panel based on the evidence identified in the literature. Modifications were made until an agreement was reached. Anonymous voting was used to evaluate each statement using the PollEv application (Poll Everywhere, https://www.polleverywhere.com). An agreement of ≥75% was set as the threshold for consensus and approved by all participants.8

Systematic Review

The reporting of the systematic review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (http://www.prisma-statement.org/) (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/TA/D908). We performed a systematic review to identify all relevant publications on the timing of fracture fixation in trauma patients with injuries to the brain, thorax, abdomen, spine/spinal cord, and vasculature.

Preliminary Screening

Several preliminary literature searches were conducted to prepare for the initiation of the Delphi process. These searches focused on the terminology for major fractures,9,10 the distinction between early surgery and damage control in isolated fractures with soft tissue injuries,5,7 the nomenclature of concepts,11 and the pathophysiology of polytrauma.12

Search Strategy

The final systematic literature search was performed on August 4, 2023, in the Medline and EMBASE databases. The time window was from January 1, 2000, to August 1, 2023. We used a combination of controlled vocabulary (MESH/Emtree-Terms) and regular search terms connected by Boolean operators. Truncation was used to account for plural forms and alternate spellings. Great care was taken to consider all relevant synonyms. Filters were applied to exclude inappropriate article types. The complete list of search terms is provided in the Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/TA/D909. In addition, we screened the reference lists of selected studies and related reviews were screened (referred to as “additional sources”).

Extraction, Screening and Retrieval

Search results were extracted and organized in EndNote version 20 by Clarivate. Articles were de-duplicated and then screened (title and abstract) independently by F.K.-L.K. and F.K. R.Pf. performed a crosscheck of the extracted data. Any disagreement was resolved in a personal meeting. The remaining articles were retrieved from the respective publishers through access to our universitiy’s central library.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Original articles, reviews, systematic reviews/meta-analyses and guidelines in English or German were assessed for inclusion. Articles were included if they dealt with the timing of fracture care in multiply injured adult patients with concomitant brain, thoracic, abdominal, spinal, and/or vascular injuries.

Commentaries, conference abstracts, correspondences, expert opinions, editorials, letters, and experimental studies (in vitro/animal) were excluded. Further exclusion criteria were pediatric and combat trauma, an insufficient characterization of the injury patterns or injured body regions, or a missing concern with timing of fracture care.

Qualitative Synthesis and Evaluation of Scientific Evidence

After full-text assessment, all included articles were evaluated, and parameters of interest were extracted. These included general information (i.e., author, year, article type, number of patients) as well as the reported outcomes, the threshold for timing (hours) of surgery, and the recommended timing of surgery (early vs. late). The scientific evidence was also evaluated using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach.8 This methodology was proposed by the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Practice Management Guidelines Ad Hoc Committee in a recent publication.13 The Grading was performed independently by two authors (F.K.-L.K. and Y.K.), and RP resolved any conflicts. The extracted data served as a foundation for creating the consensus statements in the expert panel. As the consensus statements are built on each other, the evidence was grouped according to the anatomic region of the concomitant injury. Furthermore, we assessed the agreement among the publications regarding the recommended timing of surgery (early vs. late) and the thresholds for the timing of surgery.

RESULTS

Expert Panel

The expert panel consisted of 17 experienced surgeons who were regularly involved in the management of and decision making in polytrauma patients. The scientific organizing committee was included in the expert panel and voting processes. The panel included trauma surgeons, orthopedic trauma surgeons, general surgeons, and neurosurgeons from 11 countries across four continents, as indicated by their affiliations. A detailed breakdown by country and specialty is provided in Table Table11.

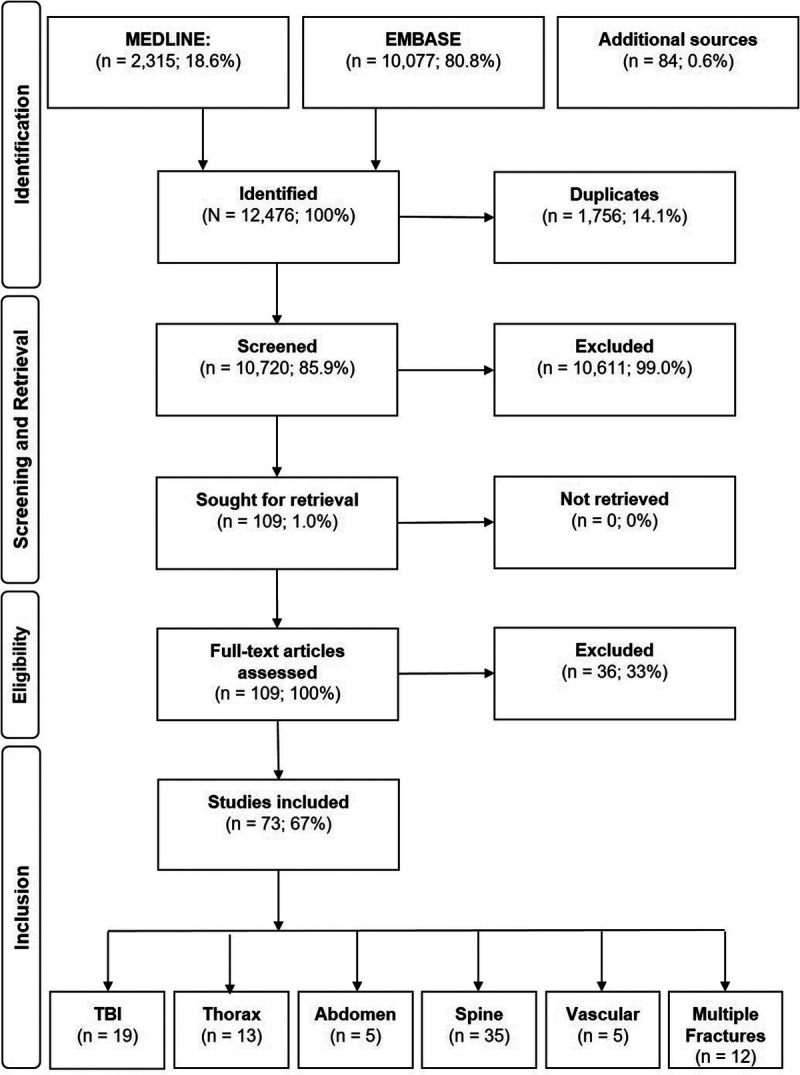

Systematic Literature Review

The entire systematic literature review process is visualized in the modified PRISMA flowchart in Figure Figure2.2. The systematic literature search yielded an initial set of 12,476 publications. After initial screening and full-text assessment, 73 publications met inclusion criteria and were thus analyzed.2–5,14–82 Of these 73 publications, 47 recommended early definitive fracture care, and 10 recommended late definitive fracture care. Most publications set the cutoff between early and late surgery within 24 hours. Therefore, 24 hours was implemented as the threshold in the consensus statements. The domains of the publications are as follows: traumatic brain injury (n = 19), thoracic trauma (n = 13), abdominal trauma (n = 5), multiple fractures (n = 12), spinal trauma (n = 35), and vascular injury (n = 5). An overview of all included publications with a grading of their level of evidence is provided in Table Table22.

TABLE 2

Summary of the Included Literature in Regards to Which Treatment Strategy Is Favored

| LoE | Outcomes | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | Article Type | N | GRADE | Early/Late | Mort | Comp | LOS | Vent | Fun | Oth | Recommended Timing |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | ||||||||||||

Scalea et al.14 Scalea et al.14 | 2004 | Retrospective | 324 | 2B | 24 h | + | Late | |||||

Brundage et al.15 Brundage et al.15 | 2002 | Retrospective | 2036 | 2A | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Wang et al.16 Wang et al.16 | 2007 | Retrospective | 96 | 2B | 24 h | + | Neutral | |||||

Morshed et al.17 Morshed et al.17 | 2009 | Retrospective | 3069 | 2A | 12 h | + | Late | |||||

Nahm et al.18 Nahm et al.18 | 2011 | Retrospective | 182 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Vallier et al.19 Vallier et al.19 | 2013 | Retrospective | 155 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Tan et al.20 Tan et al.20 | 2021 | Retrospective | 103 | 2B | 96 h | + | + | + | Early | |||

Yu et al.21 Yu et al.21 | 2023 | Retrospective | 122 | 2A | 24 h | + | + | Neutral | ||||

Ghneim et al.22 Ghneim et al.22 | 2023 | Prospective | 520 | 2C | 24 h | + | Early | |||||

Lehmann et al.23 Lehmann et al.23 | 2001 | Review | / | 2C | 24 h | + | Neutral | |||||

Grotz et al.24 Grotz et al.24 | 2004 | Review | / | 2C | 24 h | + | + | Neutral | ||||

Stahel et al.25 Stahel et al.25 | 2005 | Review | / | 2C | 5-10d | Late | ||||||

Flierl et al.26 Flierl et al.26 | 2010 | Review | / | 2C | 24 h | + | Neutral | |||||

Giannoudis et al.27 Giannoudis et al.27 | 2002 | Sys. review | 13 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Neutral | ||||

Velly et al.28 Velly et al.28 | 2010 | Sys. review | 12 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | + | Neutral | |||

Nahm et al.3 Nahm et al.3 | 2012 | Sys. review | 13 | 1B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Pfeifer et al.5 Pfeifer et al.5 | 2023 | Sys. review | 9 | 1B | 24 h | + | + | N/A | ||||

Lu et al.29 Lu et al.29 | 2020 | Metaanalysis | 14 (1046) | 2C | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Carney et al.30 Carney et al.30 | 2017 | Guideline | / | 1A | N/A | N/A | ||||||

| Thoracic Trauma | ||||||||||||

Kutscha-Lissberg et al.31 Kutscha-Lissberg et al.31 | 2001 | Retrospective | 55 | 2C | 24 h | + | + | Neutral | ||||

Pape et al.2 Pape et al.2 | 2002 | Retrospective | 514 | 2A | 24 h | + | Late | |||||

Brundage et al.15 Brundage et al.15 | 2002 | Retrospective | 2036 | 2A | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Handolin et al.32 Handolin et al.32 | 2004 | Retrospective | 61 | 2C | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Schinkel et al.33 Schinkel et al.33 | 2006 | Retrospective | 298 | 2B | 72 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Weninger et al.34 Weninger et al.34 | 2007 | Retrospective | 152 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Neutral | ||||

O’Toole et al.35 O’Toole et al.35 | 2009 | Retrospective | 227 | 2B | 24 h | + | Neutral | |||||

Nahm et al.18 Nahm et al.18 | 2011 | Retrospective | 49 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Vallier et al.19 Vallier et al.19 | 2013 | Retrospective | 447 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Sewell et al.36 Sewell et al.36 | 2018 | Retrospective | 95 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Nahm et al.3 Nahm et al.3 | 2012 | Sys. review | 7 | 1B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Pfeifer et al.5 Pfeifer et al.5 | 2023 | Sys. review | 12 | 1B | 24 h | + | + | N/A | ||||

Jiang et al.37 Jiang et al.37 | 2016 | Metaanalysis | 7 (1170) | 1A | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

| Abdominal Trauma | ||||||||||||

Morshed et al.17 Morshed et al.17 | 2009 | Retrospective | 3069 | 2A | 12 h | + | Late | |||||

Nahm et al.18 Nahm et al.18 | 2011 | Retrospective | 74 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Nahm et al.38 Nahm et al.38 | 2013 | Retrospective | 197 | 2B | Sequence | + | Neutral | |||||

Glass et al.39 Glass et al.39 | 2017 | Retrospective | 294 | 2B | Sequence | + | + | + | Fixation > abd. Closure | |||

Roberts et al.40 Roberts et al.40 | 2015 | Review | / | 1A | N/A | N/A | ||||||

| Multiple Fractures | ||||||||||||

Connor et al.41 Connor et al.41 | 2003 | Retrospective | 151 | 2B | 7d | + | + | + | Early | |||

Probst et al.4 Probst et al.4 | 2007 | Retrospective | 290 | 2B | 24 h/72 h | + | + | Late | ||||

Morshed et al.19 Morshed et al.19 | 2009 | Retrospective | 3069 | 2A | 12 h | + | Late | |||||

Vallier et al.42 Vallier et al.42 | 2010 | Retrospective | 645 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Nahm et al.18 Nahm et al.18 | 2011 | Retrospective | 576 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Vallier et al.19 Vallier et al.19 | 2013 | Retrospective | 1005 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Vallier et al.43 Vallier et al.43 | 2015 | Prospective | 335 | 2B | 36 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Childs et al.44 Childs et al.44 | 2016 | Prospective | 370 | 2B | EAC/staged | + | + | Early | ||||

Byrne et al.45 Byrne et al.45 | 2017 | Retrospective | 17993 | 2A | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Tan et al.20 Tan et al.20 | 2021 | Retrospective | 103 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Taylor et al.46 Taylor et al.46 | 2022 | Retrospective | 287 | 2B | 72 h | + | + | + | Early | |||

Nahm et al.3 Nahm et al.3 | 2012 | Sys. review | 25 | 1B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

| Spinal Trauma | ||||||||||||

Croce et al.47 Croce et al.47 | 2001 | Retrospective | 291 | 2B | 72 h | + | + | + | + | Early | ||

Chipman et al.48 Chipman et al.48 | 2004 | Retrospective | 146 | 2B | 72 h | + | + | + | Early | |||

Kerwin et al.49 Kerwin et al.49 | 2005 | Retrospective | 1742 | 2A | 72 h | + | + | + | Early | |||

McHenry et al.50 McHenry et al.50 | 2006 | Retrospective | 1032 | 2A | 48 h | + | Early | |||||

Schinkel et al.33 Schinkel et al.33 | 2006 | Retrospective | 298 | 2B | 72 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Kerwin et al.51 Kerwin et al.51 | 2007 | Retrospective | 361 | 2B | 48 h | + | + | Late | ||||

Frangen et al.52 Frangen et al.52 | 2010 | Retrospective | 160 | 2B | 72 h | + | + | + | Early | |||

Pakzad et al.53 Pakzad et al.53 | 2011 | Retrospective | 83 | 2B | 24 h/72 h | + | Early | |||||

Vallier et al.19 Vallier et al.19 | 2013 | Retrospective | 98 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Bliemel et al.54 Bliemel et al.54 | 2014 | Retrospective | 8994 | 2A | 72 h | + | + | + | Early | |||

Park et al.55 Park et al.55 | 2014 | Retrospective | 166 | 2B | 72 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Konieczny et al.56 Konieczny et al.56 | 2015 | Prospective | 38 | 2B | 72 h | + | Late | |||||

Vallier et al.43 Vallier et al.43 | 2015 | Prospective | 335 | 2B | 36 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Lubelski et al.57 Lubelski et al.57 | 2017 | Prospective | 46 | 2B | 36 h | Early | ||||||

Kobbe et al.58 Kobbe et al.58 | 2020 | Retrospective | 113 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | + | + | Early | ||

Sousa et al.59 Sousa et al.59 | 2022 | Retrospective | 50 | 2C | 72 h | + | + | Early | ||||

| Spinal Cord Injury | ||||||||||||

McKinley et al.60 McKinley et al.60 | 2004 | Retrospective | 779 | 2A | 24 h | + | Early | |||||

Fehlings et al.61 Fehlings et al.61 | 2012 | Prospective | 313 | 2A | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Rahimi-Movaghar et al.62 Rahimi-Movaghar et al.62 | 2014 | RCT | 35 | 2A | 24 h | + | + | + | Early | |||

Battistuzzo et al.63 Battistuzzo et al.63 | 2016 | Retrospective | 192 | 2B | Mdn 21 h | + | Early | |||||

Grassner et al.64 Grassner et al.64 | 2016 | Retrospective | 70 | 2B | 8 h | + | Early | |||||

Sewell et al.36 Sewell et al.36 | 2018 | Retrospective | 95 | 2B | 24 h | + | + | Early | ||||

Nayak et al.65 Nayak et al.65 | 2018 | Prospective | 54 | 2B | 24 h | + | Early | |||||

Du et al.66 Du et al.66 | 2019 | Prospective | 402 | 2A | 72 h | + | Early | |||||

Tanaka et al.67 Tanaka et al.67 | 2019 | Retrospective | 514 | 2A | 24 h | + | + | Neutral | ||||

Nasi et al.68 Nasi et al.68 | 2019 | Retrospective | 81 | 2B | 8 h | + | Early | |||||

Burke et al.69 Burke et al.69 | 2019 | Retrospective | 48 | 2B | 12 h | + | Early | |||||

Wutte et al.70 Wutte et al.70 | 2020 | Retrospective | 43 | 2B | 8 h | + | Early | |||||

Badhiwala et al.71 Badhiwala et al.71 | 2021 | Retrospective | 1548 | 2A | 24 h | + | Early | |||||

Balas et al.72 Balas et al.72 | 2022 | Retrospective | 4108 | 2A | 12 h | + | Early | |||||

Badhiwala et al.73 Badhiwala et al.73 | 2018 | Review | / | 1B | 24 h | Early | ||||||

Ramakonar et al.74 Ramakonar et al.74 | 2021 | Review | / | 1B | 24 h | Early | ||||||

Dimar et al.75 Dimar et al.75 | 2010 | Sys. review | 11 | 1B | 24 h/72 h | + | + | + | Early | |||

Carreon et al.76 Carreon et al.76 | 2011 | Sys. review | 11 | 1B | 24 h/72 h | + | + | + | Early | |||

Liu et al.77 Liu et al.77 | 2016 | Meta-analysis | 9 (734) | 1C | 24 h | + | + | + | Early | |||

| Vascular Injury | ||||||||||||

McHenry et al.78 McHenry et al.78 | 2002 | Retrospective | 27 | 2C | Sequence | + | + | Revasc. > OS | ||||

Teissier et al.79 Teissier et al.79 | 2019 | Retrospective | 16 | 2C | Sequence | + | + | Revasc. > OS | ||||

Lewis et al.80 Lewis et al.80 | 2022 | Retrospective | 104 | 2B | Sequence | + | + | Revasc. > OS | ||||

Glass et al.81 Glass et al.81 | 2009 | Sys. review | 10 | 1C | Sequence | + | + | Shunt > OS > Repair | ||||

Fowler et al.82 Fowler et al.82 | 2009 | Metaanalysis | 14 (210) | 1B | Sequence | + | + | Neutral | ||||

N, number (original article: patients, review: publications, metaanalysis: publications (patients)); LoE, Level of Evidence (according to the GRADE method); Early/Late defines the threshold applied in the respective article in hours (h) or days (d) (in case of multiple thresholds, those are presented as X/X); Outcomes: Mortality, Complications (esp. respiratory complications); LOS, length of stay (ICU and/or hospital), Ventilator days, Functional outcomes (in articles with spinal cord injury this refers to neurological recovery), and other (e.g., blood transfusions, amputation, etc.); RCT, randomized controlled trial; EAC, early appropriate care.

Consensus Statements and Level of Agreement

The initial 12 statements, formed during the preparation phase (online meeting 1/2), were extended by an additional eight statements. A total of 20 statements were voted on during the in-person meeting in Zurich. Among these 20 statements, 15 statements (75%) reached full consensus (100% agreement), and 5 statements (25%) reached a level of 92% to 95% agreement. These statements are presented in Table Table3,3, along with the agreement within the expert panel, the level of evidence in the literature, and the overall agreement in the literature.

TABLE 3

Consensus Statements, Agreement in the Panel, Evidence Level and Congruency in Literature

| No | Statement | Agreement in Expert Panel (%) | Evidence Level of Literature | Agreement in Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traumatic brain injury | ||||

| 1 | In patients with mild TBI (GCS ≥ 13) and initial head CT without evidence of acute intracranial trauma sequelae with adequate respiratory and hemodynamic parameters, early (<24 h) definitive fracture fixation of isolated major fractures is recommended. | 94 | N = 19 GRADE (n): 1A = 1 1B = 5 1C = 6 2A = 3 2B = 4 | Early: n = 7 Neutral: n = 9 Late: n = 3 Thresholds: 24 h: n = 15 72 h: n = 0 Other: n = 4 |

| 2 | In patients with mild TBI (GCS ≥ 13) and initial head CT without evidence of acute intracranial trauma sequelae with adequate respiratory and hemodynamic parameters, early (<24 h) definitive fracture fixation of multiple major fractures is permissible as long as the patient remains physiologically stable during serial reassessment. If the patient becomes unstable, consider DCO. | 100 | ||

| 3 | In mild TBI patients (GCS ≥ 13) with acute intracranial trauma sequelae findings on initial head CT, early (<24 h) definitive fixation of major fractures is permissible after exclusion of significant intracranial pathologies and lack of further progression on follow-up head CT. | 100 | ||

| 4 | TBI patients should NOT undergo definitive fixation of major fractures in the presence of intracranial hypertension (ICP > 20 mmHg), deterioration of neurological status, progression of the initial trauma sequelae findings on head CT, hemodynamic and/or respiratory instability, and coagulopathy. | 100 | ||

| 5 | In patients with significant TBI, delayed definitive fracture fixation of major fractures is acceptable in patients with stable GCS, without deterioration of neurological status and findings in the follow-up head CT, or stable ICP (ICP ≤ 20 mmHg) and CPP (>60–70 mmHg) in patients with invasive neuromonitoring. | 100 | ||

| Thoracic trauma | ||||

| 6 | In patients with chest injuries and adequate oxygenation/ventilation and stable lung function (with or without ventilator support), early (<24 h) definitive fracture fixation of isolated major fractures is recommended. | 100 | N = 13 1A = 1 1B = 3 1C = 0 2A = 2 2B = 5 2C = 2 | Early: n = 8 Neutral: n = 4 Late: n = 1 Thresholds: 24 h: n = 12 72 h: n = 1 Other: n = 0 |

| 7 | In patients with bilateral severe chest injury, early (<24 h) fixation by external fixation according to DCO principles should be considered. In cases of inadequate oxygenation and unstable lung function on ventilatory support, fracture stabilization according to DCO principles, usually by external fixation, is recommended. | 94 | ||

| 8 | In patients with chest injuries, early (<24 h) definitive fracture fixation of multiple major fractures is permissible as long as the patient remains physiologically stable. Continuous perioperative monitoring is recommended in these patients according to the previously selected parameters. | 100 | ||

| Abdominal Trauma | ||||

| 9 | In patients with blunt abdominal injuries that do not require surgery and the patient is physiologically stable as previously defined, early (<24 h) definitive fracture fixation of isolated major fractures is recommended. | 100 | N = 5 1A = 1 1B = 0 1C = 0 2A = 1 2B = 3 2C = 0 | Early: n = 2 Neutral: n = 2 Late: n = 1 Thresholds: 24 h: n = 1 72 h: n = 0 Other: n = 4 |

| 10 | In patients with blunt and penetrating abdominal injuries who respond to resuscitation and in whom hemorrhage control has been achieved, definitive fixation of isolated fractures is recommended as long as the patient remains physiologically stable. | 94 | ||

| 11 | For patients mentioned in recommendations 9 and 10 who have multiple major fractures, serial intraoperative monitoring is recommended to determine the feasibility of the fixation of several fractures in one operation. | 100 | ||

| 12 | In patients with blunt and penetrating abdominal injuries that require surgical intervention, early (<24 h) stabilization based on DCO principles is recommended in the presence of major visceral organ injury, major soft tissue injury, prolonged surgery, or major intraoperative blood loss. | 94 | ||

| Multiple Fractures | ||||

| 13 | In patients with multiple major fractures, the sequence of fracture fixation should be based on the risk of: • Loss of life (such as severe bleeding e.g. from extremity injury) • Catastrophic disability (e.g. incomplete spinal cord injury or deteriorating neurological status in unstable spinal injuries) • Limb loss (e.g. compartment syndrome, vascular injury, open fracture) • Loss of function (e.g., peripheral neurological compromise) | 100 | N = 12 1A = 0 1B = 1 1C = 0 2A = 2 2B = 9 2C = 0 | Early: n = 10 Neutral: n = 0 Late: n = 2 Thresholds: 24 h: n = 7 72 h: n = 1 Other: n = 4 |

| 14 | In patients with multiple major fractures and stable physiology, the prioritization should take into account: • The location of the fracture • The complexity of the fracture (e.g. open, highly comminuted) • The duration of the surgical procedure • The anticipated associated hemorrhage • The expertise of the surgical team • The availability of resources | 100 | ||

| 15 | In patients with multiple major fractures (including bilateral injuries) and stable physiology, serial perioperative assessments are required to consider and allow for sequential fixation of fractures | 100 | ||

| Spinal (Cord) Injury | ||||

| 16 | Early (<24 h) reduction, decompression, and spinal fixation are required in patients with potentially complete spinal cord injury and have priority over definitive fixation of other fractures. Before initiating this surgical procedure, other life-threatening conditions must be addressed ensuring a stable physiological condition has been established. | 100 | N = 35 1A = 0 1B = 4 1C = 1 2A = 10 2B = 19 2C = 1 | Early: n = 32 Neutral: n = 1 Late: n = 2 Thresholds: 24 h: n = 16 72 h: n = 10 Other: n = 9 |

| 17 | Patients with spinal cord injury with partial neurological deficit and deteriorating neurological function in the presence of severe spinal instability (type B or C injuries) are considered a special cohort, and emergent surgery is recommended. In this situation, spine fixation is required and takes priority. Before initiating this surgical procedure, other life-threatening conditions must be addressed ensuring a stable physiological condition has been established. | 100 | ||

| 18 | In patients with spinal cord injury and multiple major fractures, serial assessments of physiologic fitness are required to allow for the sequential fixation of other fractures. | 92 | ||

| Vascular Injury | ||||

| 19 | In patients with extremity arterial injury and brief ischemia time with expected rapid fracture fixation, skeletal stabilization or otherwise temporary stabilization (damage control for the extremity) should be attempted before vascular repair if achievable in a short timeframe. In addition, prophylactic fasciotomies should be considered. | 100 | N = 5 1A = 0 1B = 1 1C = 1 2A = 0 2B = 1 2C = 2 | OS first: n = 1 Neutral: n = 1 Revasc. first: n = 3 Thresholds: Sequence Revasc./osteosynthesis |

| 20 | In patients with extremity arterial injury who are approaching 6 h of critical ischemia time, restoring distal arterial flow has priority over fracture fixation. Intra-arterial shunts followed by temporary fracture stabilization or definite fixation and then definitive vascular repair versus definitive vascular repair followed by fracture stabilization should be decided on a case-by-case basis. In these cases, fasciotomies are required. | 100 | ||

CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure; CT, computed tomography; DCO, damage-control orthopedics; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

As there are always multiple studies that provide evidence to support each statement, we did not assign a level of evidence to each individual statement but rather subsumed them according to the anatomic location.

Regarding the agreement within the literature, we noted the highest agreement regarding spinal (cord) injuries, in which 32 of 35 publications recommended early definitive fracture care. The lowest agreement and the lowest number of identified publications were noted regarding vascular injury (3 of 5 publications recommended revascularization before fracture care). All further levels of evidence and the agreement within the literature can be seen in Table Table22.

DISCUSSION

Fracture management constitutes a major part of the treatment of polytrauma patients, as shown by large trauma registries. In the German Trauma Registry, for instance, ~30% of patients suffered a severe injury (Abbreviated Injury Scale ≥ 3) to the extremities, pelvis, and spine. Sixty-five percent of these patients required an average of 2.9 surgeries.83 From the patient's perspective, timely fracture care is advisable to facilitate rapid recovery. Nevertheless, objective criteria to delay fracture fixation have been defined.84

Multiple improvements have been demonstrated to have enabled more expeditious and safe surgical treatment within the first 24 hours after injury.85 Even under physiological conditions and with adequate hemodynamics in the early stages after injury, associated trauma or specific injury patterns may cause a delay in fracture fixation.

In this international expert panel by the IMPACT group, consensus on the timing of fracture fixation in patients with associated traumatic brain, thorax, abdomen, spine/spinal cord, and extremity vascular injuries was reached using the Delphi method. All statements formulated by the expert panel were critically analyzed based on a systematic literature review and their level of evidence. Overall, 73 publications were reviewed, and 20 statements were approved (Tables (Tables2,2, ,3).3). These are discussed below based on the type of associated injury.

Traumatic Brain Injury

Avoiding secondary brain damage is crucial, and several publications support our recommendations.25,30 Currently, early definitive treatment of major fractures is only recommended for patients with mild traumatic brain injury.5,21 In cases of more severe intracranial injuries, the concern for cerebral complications is great, and their prevention is of utmost importance.27,28

Several publications have investigated the effects of delayed fracture fixation after mild traumatic brain injury but have failed to prove an effect on complication rates or neurological outcomes.16,21 While the second-hit phenomenon is well described, some authors have raised doubts about its relevance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury.21 The brain versus bone multicenter trial involved 520 patients with lower extremity fractures and mild to severe traumatic brain injury. They examined the effect of the timing of lower extremity fracture fixation on neurological outcomes.22 The results suggest that neurological outcomes are largely dependent on the severity of the initial brain injury rather than the surgical care provided to treat associated injuries.

In general, in the presence of significant intracranial pathologies, delayed definitive fracture fixation is recommended if further progression is observed on follow-up head CT.27,28 An increase in intracranial pressure (ICP >20 mm Hg) and a decrease in cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP < 60/70 mm Hg) is associated with a significant increase in mortality.5 These thresholds are also recommended in the recent Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury.30 Accordingly, secondary reconstructions of fractures are justified in patients with stable Glasgow Coma Scale, no deterioration seen on follow-up head CT, or improvements of the parameters mentioned above (ICP, CPP).

Thoracic Trauma

The primary goal in the management of patients with chest trauma is to maintain oxygenation and ventilation and to prevent secondary complications, such as pneumonia, acute lung injury, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.86 Recent systematic reviews of prospective and retrospective studies suggest that early definitive treatment of fractures may be used safely for most patients with chest injuries, depending on the criteria mentioned previously84 and refined later.87 It is unclear whether certain surgical techniques affect pulmonary function, as the only studies available were on reamed versus unreamed femoral nailing and studies comparing different reamer types.2,88,89

A meta-analysis did not show significantly increased rates of pulmonary complications such as pneumonia and mortality in patients with thoracic trauma.37 However, patients with bilateral chest injuries require special attention as they have a higher rate of complications, especially in the presence of bilateral pulmonary contusions and/or hemothoraces and pneumothoraces.90 In those patients, it is recommended that temporary external fixation of fractures be performed.

Abdominal Trauma

The primary aim of abdominal trauma management is to control bleeding and contamination from enteral injuries.40 Information about the timing of fracture fixation in patients with abdominal trauma is limited. Roberts et al. published physiological parameters and rated indications for the use of damage-control surgery.40 According to their study, difficult-to-access major venous injuries, major liver or combined pancreaticoduodenal injuries, as well as devascularization or massive disruptions of the duodenum or pancreas, require damage-control interventions.40 If hemorrhage control can be achieved, or if nonoperative management is possible, it is recommended to perform definitive fixation of isolated fractures as long as the patient remains physiologically stable. For patients with multiple major fractures, it is recommended to conduct serial monitoring of the patient's physiologic response (hemodynamic, respiratory, renal, coagulation, and metabolic). It has been found that definitive fracture fixation is safe regarding surgical site infection, even in the presence of an open abdomen.39 As an exception, patients with pelvic ring injuries and associated abdominal trauma require special care to avoid gross contamination from enteric injuries.91 Still, even in this group, internal fixation helps heal soft tissue and control infection.

Multiple Fractures

The primary goal in treating patients with multiple fractures is early and safe bone reconstruction and patient mobilization. The sequence of fracture fixation is challenging, and clinical studies are difficult to perform in this patient population.18 However, multiple aspects must be considered when determining the surgical sequencing and timing for these complex patients. For instance, an international survey of 196 trauma surgeons from 61 countries found that assessing the surgical load (a physiological burden to the patient incurred by the surgical procedure) is very important.92 Factors to consider include the avoidance of shock, lung dysfunction, coagulopathy, hypothermia, soft tissue injuries, as well as potential intraoperative blood loss.92 It is crucial to prioritize life over limb when sequencing the fixation of major fractures after polytrauma. In addition, the management of major fractures is dictated by the prevention of severe disability (e.g., from spinal cord injury), followed by the risk of limb loss (e.g., compartment syndrome, arterial injury, or thrombosis). Should the patients' clinical status not improve after resuscitative efforts, damage-control orthopedics are a valid and important alternative for long bone fracture stabilization.35 In some situations, a staged procedure in the musculoskeletal system is performed mainly due to local factors (contaminated wounds, bone defects, etc.) and has been named “musculoskeletal temporary surgery.”7 These complex injuries also affect the sequence of fracture fixation.

Spinal Injuries

In polytrauma patients, the spine is affected in up to 30% of cases.93 Unstable fractures often require invasive procedures, which may be impossible in polytrauma patients due to the high surgical load, including long operative time, invasive approach, and risk of bleeding. Most publications recommend early fixation and treatment of unstable spinal fractures, regardless of the presence of neurologic deficit.62,75,76 Our literature review indicates that injuries to the thoracic spine, especially those with neurological deficits, should be stabilized early.48,94 A recent publication clearly showed that spinal injury requires early definitive surgery within 24 hours after admission, especially in patients with neurological deficits.85 Early surgery in the form of posterior spinal stabilization performed within 24 hours improves outcomes by avoiding immobilization, improving lung function, and shortening hospital and intensive care stays.77,94

Vascular Injuries

The timing of fracture fixation in patients with associated major vascular injury remains a topic of debate. Some authors suggest temporary fixation of the fracture before final vascular repair to avoid potential graft complications.82 Conversely, others recommend immediate revascularization to decrease ischemia time.78–80 In studies dealing with fracture repair and associated vascular trauma, the emphasis is mostly not on the timing but on the sequence of fracture fixation or revascularization.81 Our systematic review indicates that prolonged fracture fixation before revascularization increases vascular morbidity.80 Furthermore, the time taken to restore distal arterial flow has been consistently identified as the only modifiable risk factor for both graft failure and limb amputation in patients with a combined fracture of a long bone and severe arterial injury.80 Therefore, in cases of extremity fractures with arterial injuries, approaching the critical ischemia time of 6 hours, restoration of distal arterial flow takes priority over fracture fixation. This can be accomplished by the use of temporary intravascular shunts or definitive repair (primary repair, interposition graft), depending on the duration of ischemia and the complexity of the fractures.

Limitations

One limitation is the composition of the expert panel itself. Although it was important to control for an even distribution of experts in terms of geographical location, representation of different surgical specialties, and individual professional focus, slight imbalances had to be accepted regarding feasibility and coordination of the expert panel. The statements were synthesized from the expertise of the participants and the existing literature. Depending on the specific topic, the amount and quality/evidence of published literature varied greatly, resulting in a greater weighting of the expert opinions. Although most of the central issues of surgical care and trauma patterns were included in the statements, the recommendations may not cover rare or uncommon cases.

CONCLUSION

This international expert panel reached an overwhelming consensus that early definitive fracture fixation (within 24 hours) should be attempted even in polytrauma patients if the posttraumatic clinical condition allows. Our 20 statements provide clear indications and contraindications for the most relevant associated injuries and are supported by the literature.

The following order of priorities should be respected: (1) life, (2) central nervous system, (3) limb, and (4) functionality. While the physiological responses (hemodynamic, respiratory, renal, coagulation, metabolic) remain important, emphasis should also be put on the neurological status and injury-specific factors when deciding on the timing of fracture fixation in polytrauma patients. Serial assessments are mandatory to reflect the dynamics early on and to adapt the treatment strategy accordingly.

AUTHORSHIP

R.Pf., F.-K.L.K., Z.J.B., R.C., E.H.S., H.A.V., Y.K., H.-C.P. participated in the conceptualization. R.Pf., F.-K.L.K., Z.J.B., R.C., E.H.S., H.A.V., Y.K., H.-C.P. participated in the methodology. R.Pf., F.-K.L.K., Z.J.B., F.J.P.B., R.C., C.F., P.V.G., F.Hie., F.Hil., H.K., T.L., I.M., M.F.O., R.Pe., S.R., E.H.S., H.A.V., B.A.Z., Y.K., H.-C.P. participated in the investigation. F.-K.L.K., Y.K. participated in the visualization. R.Pf., H.-C.P. participated in the project administration. R.Pf., H.-C.P. participated in the supervision. R.Pf., F.-K.L.K., Y.K., H.-C.P. participated in the writing—original draft. R.Pf., F.-K.L.K., Z.J.B., F.J.P.B., R.C., C.F., P.V.G., F.Hie., F.Hil., H.K., T.L., I.M., M.F.O., R.Pe., S.R., E.H.S., H.A.V., B.A.Z., Y.K., H.-C.P. participated in the writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was performed by the consortium of the IMPACT group, an international expert group on polytrauma management:

DISCLOSURE

Conflict of interest: All JTACS Disclosure forms have been supplied and are provided as supplemental digital content (http://links.lww.com/TA/D911).

Footnotes

Published online: August 1, 2024.

R.Pf., F.K.-L.K., Y.K., H.-C.P. contributed equally

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jtrauma.com).

REFERENCES

Citations & impact

This article has not been cited yet.

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/165846822

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Orthopedic injuries in patients with multiple injuries: Results of the 11th trauma update international consensus conference Milan, December 11, 2017.

J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 88(2):e53-e76, 01 Feb 2020

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 32150031

Review

Building consensus on the selection criteria used when providing regional anaesthesia for rib fractures. An e-Delphi study amongst a UK-wide expert panel.

Injury, 55(1):110967, 31 Jul 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37563045

Is There an Impact of Concomitant Injuries and Timing of Fixation of Major Fractures on Fracture Healing? A Focused Review of Clinical and Experimental Evidence.

J Orthop Trauma, 30(3):104-112, 01 Mar 2016

Cited by: 13 articles | PMID: 26606600

Review

Developments in the understanding of staging a "major fracture" in polytrauma: results from an initiative by the polytrauma section of ESTES.

Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg, 50(3):657-669, 23 Feb 2023

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 36820896 | PMCID: PMC11249440

Review Free full text in Europe PMC